Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Thib Basic Principles

Thib Basic Principles

Uploaded by

Ricardo E Arrieta CCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Body For Life - Full BookDocument224 pagesBody For Life - Full Bookapi-370924497% (32)

- Strength Series 4 - Accumulation 7 - 5 X 3-5Document2 pagesStrength Series 4 - Accumulation 7 - 5 X 3-5denisNo ratings yet

- Thibaudeau's Guide To Hypertrophy-Clean Health Fitness InstituteDocument219 pagesThibaudeau's Guide To Hypertrophy-Clean Health Fitness InstituteVíctor Tarín100% (15)

- Free Glute WorkoutDocument12 pagesFree Glute Workoutxzx4vsxnhmNo ratings yet

- Picp Level 1 ManualDocument53 pagesPicp Level 1 ManualFélix Gouhier100% (2)

- Rugby Renegade WOD BibleDocument32 pagesRugby Renegade WOD BibleAgustin Garcia100% (2)

- Charles Poliquin - The Super Accumulation ProgramDocument6 pagesCharles Poliquin - The Super Accumulation ProgramAndrea100% (4)

- Christian Thibaudeau - Training The Three Types of ContractionsDocument12 pagesChristian Thibaudeau - Training The Three Types of ContractionsPeter Walid100% (4)

- Biosignature ModulationDocument3 pagesBiosignature ModulationMiguel Kennedy75% (4)

- Meso Endomorph Workout PlanDocument8 pagesMeso Endomorph Workout Planrtkiyous2947No ratings yet

- X TraordinaryArmsDocument55 pagesX TraordinaryArmsRicardo E Arrieta C100% (6)

- The List - Eric Falstrault - Strength SenseiDocument11 pagesThe List - Eric Falstrault - Strength SenseiJon shieldNo ratings yet

- Strength Senseis Pre Workout Nutrition PDFDocument49 pagesStrength Senseis Pre Workout Nutrition PDFFilip Velickovic100% (3)

- In-Season Training For MaintenanceDocument4 pagesIn-Season Training For MaintenancejapNo ratings yet

- Klatt Test Assesment Tool For Lower BodyDocument6 pagesKlatt Test Assesment Tool For Lower BodyEmiliano BezekNo ratings yet

- Muscle Fiber TestDocument4 pagesMuscle Fiber TestKamaruzaman Soeed100% (3)

- FinalDocument4 pagesFinalKang Kamalinder100% (1)

- Achieving Structural Balance - Upper Body PushDocument22 pagesAchieving Structural Balance - Upper Body Pushdjoiner45100% (5)

- Poliquin® International Certification ProgramDocument1 pagePoliquin® International Certification ProgramRajesh S VNo ratings yet

- A. Strength Qualities: Rep, Intensity & Training Effect RelationshipDocument10 pagesA. Strength Qualities: Rep, Intensity & Training Effect RelationshipQuốc Huy100% (6)

- Level 1 Workbook - Remedial Lifts-MinDocument4 pagesLevel 1 Workbook - Remedial Lifts-MinQuốc Huy100% (3)

- Poliquin PrinciplesDocument120 pagesPoliquin PrinciplesPauloCarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Popular Training Systems Adapted To Neurotype - Part 1 - German Volume Training - ThibarmyDocument25 pagesPopular Training Systems Adapted To Neurotype - Part 1 - German Volume Training - ThibarmyKomkor Guy100% (1)

- Book of Programmes for the Team Sport Athlete; Size & StrengthFrom EverandBook of Programmes for the Team Sport Athlete; Size & StrengthNo ratings yet

- Q A Charles PoliquinDocument106 pagesQ A Charles PoliquinMoosa Fadhel100% (3)

- Theory and Application of Modern Strength and Power Methods Modern MethodsDocument160 pagesTheory and Application of Modern Strength and Power Methods Modern Methodsicemn28100% (1)

- Hypertrophy Execution Mastery - Module 2 Workouts - Biceps & Triceps PDFDocument24 pagesHypertrophy Execution Mastery - Module 2 Workouts - Biceps & Triceps PDFMarvin100% (1)

- Tyler Kuntz Resignation LetterDocument3 pagesTyler Kuntz Resignation LetterKoby MichaelsNo ratings yet

- LSF 4 Week Booty IntensiveDocument35 pagesLSF 4 Week Booty IntensiveMargaridaFerreira100% (3)

- 2022 12 30 Website PDFDocument80 pages2022 12 30 Website PDFmostafakhafagy8100% (2)

- NEUROTYPINGDocument10 pagesNEUROTYPINGThibault AÏT-SAÏDNo ratings yet

- What Is Functional HypertrophyDocument7 pagesWhat Is Functional Hypertrophynima_44100% (1)

- Problem Solving Bench PressDocument66 pagesProblem Solving Bench Pressluis_tomaz100% (1)

- Thib Notes - Cluster ProgramingDocument4 pagesThib Notes - Cluster Programingdeclanku100% (1)

- Charles Poliquin - No Holds Barred Interview (2005)Document4 pagesCharles Poliquin - No Holds Barred Interview (2005)Alen_D100% (5)

- Muscle Fibre TestDocument3 pagesMuscle Fibre TestEduardo SantosNo ratings yet

- Zatsiorsky Intensity of Strength Training Fact and Theory Russ and Eastern Euro ApproachDocument20 pagesZatsiorsky Intensity of Strength Training Fact and Theory Russ and Eastern Euro ApproachJoão CasqueiroNo ratings yet

- Christian Thibaudeau - Shoulder Blasting Circuit CombosDocument1 pageChristian Thibaudeau - Shoulder Blasting Circuit CombosJTB01No ratings yet

- Building A Better Athlete With Functional Hypertrophy - Strength Sensei IncDocument5 pagesBuilding A Better Athlete With Functional Hypertrophy - Strength Sensei IncSean DrewNo ratings yet

- The Best Training Program Doesnt ExistDocument25 pagesThe Best Training Program Doesnt Existjap100% (2)

- Top Ten Nutrients That Support Fat Loss - Poliquin ArticleDocument4 pagesTop Ten Nutrients That Support Fat Loss - Poliquin Articledjoiner45No ratings yet

- Preventing Injuries in Arm Training - The Real Strength SenseiDocument8 pagesPreventing Injuries in Arm Training - The Real Strength SenseiSean DrewNo ratings yet

- Day 1: Chest/Back Sets/Reps Weight Sets/Reps Weight Sets/Reps Weight Sets/RepsDocument4 pagesDay 1: Chest/Back Sets/Reps Weight Sets/Reps Weight Sets/Reps Weight Sets/RepsPJ Burrows100% (2)

- Charles Poliquin - A Brief History of Periodization PDFDocument3 pagesCharles Poliquin - A Brief History of Periodization PDFJDredd0167% (3)

- Using The Force-Velocity Curve To Build Better Athletes - Elite FTS PDFDocument8 pagesUsing The Force-Velocity Curve To Build Better Athletes - Elite FTS PDFok okNo ratings yet

- Fat Loss Series 3 Intensification 6 Double Trisets PDFDocument2 pagesFat Loss Series 3 Intensification 6 Double Trisets PDFHolistic Body Marcin Michalski100% (1)

- Wave Ladders For Maximum StrengthDocument8 pagesWave Ladders For Maximum StrengthEduardo BonifacioNo ratings yet

- 6 Weeks To Great Abs - T NationDocument29 pages6 Weeks To Great Abs - T NationMamazaccoRacerpoilNo ratings yet

- Bio Signature Womens FitnessDocument1 pageBio Signature Womens Fitnessnick5134No ratings yet

- Judd LoganDocument4 pagesJudd LoganShawn SchraufnagelNo ratings yet

- The Benefits of BCAAs - Poliquin ArticleDocument8 pagesThe Benefits of BCAAs - Poliquin Articlecrespo100% (2)

- Functional Hypertrophy - Phase 2-Day 1 Chest & Back: Exercise Cycle Sets Reps Tempo Rest W/R W/R W/R W/RDocument3 pagesFunctional Hypertrophy - Phase 2-Day 1 Chest & Back: Exercise Cycle Sets Reps Tempo Rest W/R W/R W/R W/RNeetu Kang100% (3)

- Training - Principles - The Science of Tempo and Time Under Tension PDFDocument10 pagesTraining - Principles - The Science of Tempo and Time Under Tension PDFFernando Simao Victoi100% (1)

- How To Lift For Maximal Hypertrophy: Free ResourceDocument10 pagesHow To Lift For Maximal Hypertrophy: Free Resourcebaris arslanoglu100% (2)

- Chris Thibaudeau. 9 Ways To Keep Getting BetterDocument2 pagesChris Thibaudeau. 9 Ways To Keep Getting BetterPaolo Altoé100% (1)

- Isometrics The Most Underrated Training Tool ThibarmyDocument6 pagesIsometrics The Most Underrated Training Tool Thibarmynounou100% (2)

- Thibarmy - Five Quick Tips For Better AbsDocument3 pagesThibarmy - Five Quick Tips For Better AbsAnn Petrova0% (1)

- Ep 52 Charles Poliquin - Training Methods Part 1: Listen To This Podcast Episode HereDocument29 pagesEp 52 Charles Poliquin - Training Methods Part 1: Listen To This Podcast Episode HereLukas100% (1)

- The Alternating Conjugate Periodization ModelDocument9 pagesThe Alternating Conjugate Periodization ModelJordanKruegerNo ratings yet

- Twelve Week Training Program - DEADLIFTS - Article - Poliquin MobileDocument5 pagesTwelve Week Training Program - DEADLIFTS - Article - Poliquin MobileJon shieldNo ratings yet

- 6 Page - POLIQUIN INTERNATIONAL CERTIFICATION PROGRAM Performance Specialization Level 1Document6 pages6 Page - POLIQUIN INTERNATIONAL CERTIFICATION PROGRAM Performance Specialization Level 1nam nguyenNo ratings yet

- Shoulder Savers PDFDocument5 pagesShoulder Savers PDFlunn100% (6)

- 10 X 10 PoliquinDocument3 pages10 X 10 PoliquinSergio Ramos Ustio100% (2)

- Charles Poliquin-The Super-Accumulation Program - T NationDocument6 pagesCharles Poliquin-The Super-Accumulation Program - T NationManuel Ferreira PT100% (3)

- Advanced Training Techniques - FREE EBOOKDocument33 pagesAdvanced Training Techniques - FREE EBOOKCláudio Milane De OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Hamstring Paradigm: Train Hamstrings Both As Knee Flexors and Hip ExtensorsDocument5 pagesHamstring Paradigm: Train Hamstrings Both As Knee Flexors and Hip ExtensorsSaltForkNo ratings yet

- Bodybuilding Training SystemsDocument5 pagesBodybuilding Training Systemskamak777750% (2)

- Neurotypes and Fighting Styles - Christian Thibaudeau Coaching - Forums - T NationDocument3 pagesNeurotypes and Fighting Styles - Christian Thibaudeau Coaching - Forums - T NationVladimir OlefirenkoNo ratings yet

- Universidad Del IstmoDocument3 pagesUniversidad Del IstmoRicardo E Arrieta CNo ratings yet

- BeyondX RepDocument114 pagesBeyondX RepRicardo E Arrieta C100% (1)

- The Massive Growth SystemDocument273 pagesThe Massive Growth SystemalaberhtNo ratings yet

- Peachplease Gym Week1 1Document14 pagesPeachplease Gym Week1 1TejaRejc100% (1)

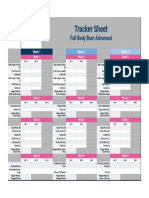

- Tracker Sheet: Full Body Burn AdvancedDocument1 pageTracker Sheet: Full Body Burn AdvancedddsNo ratings yet

- Proper Etiquette in A Fitness FacilityDocument3 pagesProper Etiquette in A Fitness FacilityMartin RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Lean Eating For Women - Fourth Phase (4 Weeks) : They're Not Called Weights Because They're LightDocument26 pagesLean Eating For Women - Fourth Phase (4 Weeks) : They're Not Called Weights Because They're LightĐạt NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Tracy's Swing ProgressionsDocument4 pagesTracy's Swing ProgressionsPicklehead McSpazatronNo ratings yet

- Dumbbellonly 0 PDFDocument1 pageDumbbellonly 0 PDFamerican2300No ratings yet

- UEX Back-Tricep Workout PDFDocument7 pagesUEX Back-Tricep Workout PDF10 Chandra Prakash Pandian PNo ratings yet

- A History of The Bench PressDocument2 pagesA History of The Bench Presslw98No ratings yet

- StretchingDocument38 pagesStretchingVennia Papadipoulou40% (15)

- The "Spartacus" Workout 3 Day Circuit TrainingDocument3 pagesThe "Spartacus" Workout 3 Day Circuit TrainingNatali KruNo ratings yet

- Be A Hero Fitness - Baki The Grappler Mass Workout - Here We Are.. - PDFDocument1 pageBe A Hero Fitness - Baki The Grappler Mass Workout - Here We Are.. - PDFAndres Diego100% (1)

- FLEXIBILITY and STRETCHING EXERCISES PDFDocument3 pagesFLEXIBILITY and STRETCHING EXERCISES PDFRubamoNo ratings yet

- Physical Assessment Tools For To and Through Selection - Stew Smith FitnessDocument14 pagesPhysical Assessment Tools For To and Through Selection - Stew Smith FitnesscallenNo ratings yet

- Three Muscle Toning Arm Workouts For Women - Muscle & Strength PDFDocument7 pagesThree Muscle Toning Arm Workouts For Women - Muscle & Strength PDFAliNo ratings yet

- Greg Nuckols 28 Programs by StrengtheoryDocument78 pagesGreg Nuckols 28 Programs by StrengtheoryThe ChampNo ratings yet

- The Brazilian Butt Ebook1Document72 pagesThe Brazilian Butt Ebook1Camden White57% (14)

- Effect of Hamstring Emphasized Resistance Training On H-Q Strength RatioDocument7 pagesEffect of Hamstring Emphasized Resistance Training On H-Q Strength RatioRaja Nurul JannatNo ratings yet

- NCC - NCX (11 7 22)Document1 pageNCC - NCX (11 7 22)azizNo ratings yet

- Gym Plan: Week 1: Full-Body SplitDocument9 pagesGym Plan: Week 1: Full-Body SplitSalih MohayaddinNo ratings yet

- The 12 Untapped Targets To Ignite New Muscle GrowthDocument68 pagesThe 12 Untapped Targets To Ignite New Muscle Growthace_mimNo ratings yet

- Interval Training Workouts Build Speed and EnduranceDocument2 pagesInterval Training Workouts Build Speed and EndurancenewrainNo ratings yet

- HurdlesDocument4 pagesHurdlesapi-313469173No ratings yet

- 2017 National Poomsae GroundrulesDocument7 pages2017 National Poomsae GroundrulesEljan VentureNo ratings yet

- Australian Ironman Magazine July 2016 PDFDocument140 pagesAustralian Ironman Magazine July 2016 PDFgeorgeNo ratings yet

Thib Basic Principles

Thib Basic Principles

Uploaded by

Ricardo E Arrieta COriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Thib Basic Principles

Thib Basic Principles

Uploaded by

Ricardo E Arrieta CCopyright:

Available Formats

The Thib System Variety and Rules for Progression Basic Principles Behind My Updated Training Philosophy A lot

t of people have trouble "getting" me, at least when it comes to training. This might be because of my diverse training background. While most coaches tend to come from a single background (powerlifting, athletics, bodybuilding, etc.), I've actually trained and competed in most of them. When I was a football player, I was trained by a great athletic strength coach named Jean Boutet. Not many people know of him because he never cared to market himself, but the guy worked with several Olympians and pro athletes. His knowledge base is only surpassed by guys like Charles Poliquin. From the age of 14, I was able to train under his supervision. To say I learned a lot is an understatement. While competing in Olympic lifting, I trained under Pierre Roy, the former national team coach, whom coach Poliquin called "the smartest man in strength training." I was also able to train alongside several Olympians, former Olympians, and other world-class lifters. So again, I had a wealth of knowledge to devour. Along my way, I gained a tremendous amount of knowledge from Charles Poliquin, so much so that he became my mentor. I can relate to him because his background is also remarkably diverse. The fact that he's worked with hundreds of Olympians, pro athletes, and bodybuilders makes him a unique source of overall training knowledge. I soak up as much info from him as possible. In addition to my tutelage, I've dabbled in bodybuilding, having lived the lifestyle and competed in a few shows. I've also partaken in a couple strongman competitions for some fun on the side. The end result is that I often come out like someone who's a generalist more than a specialist. I'm not just a bodybuilding coach, or just an Olympic lifting coach. I'm a symbiosis of all possible training methods. Understandably, those who want to design their own "Thibaudeau routine" can have trouble doing so because it's hard to pinpoint my exact training style. While I do use a wide array of methods, I have several basic principles that regulate my way of programming. And here they are!

Principle #1: The Point of Fatigue Induction is Exercise Dependant One of the most hotly debated aspects of training is whether or not to train to failure. Failure is simply the incapacity to maintain the required amount of force output (Edwards 1981, Davis 1996).

In other words, at some point during your set, completing more repetitions will become more and more arduous until you're unable to produce the required amount of force to complete a repetition. Even Testosterone has proponents of both approaches! On one side, you have guys like Chad Waterbury and Charles Staley who are against training to failure. Heck, sometimes they even recommend stopping a set when the reps start to slow down, which is way before muscle failure! Their main point is that training to failure puts a tremendous stress on the central nervous system (CNS). The nervous system takes as much as five to six times longer than the muscles to recover from an intense session. So by constantly going to muscle failure, you can overload the CNS so much that it becomes impossible to train with a high frequency. And they're right! In fact, it's possible to drain the nervous system so much that it takes so long to recover that the muscles actually start to detrain while the CNS is still recovering. So you end up in a catch-22. On one hand, you need to train otherwise your muscles will start to lose the gains that were stimulated by the previous session. But on the other, if you train before your CNS has recovered, you'll have a subpar session which won't lead to much progress and might even cause you to regress over time. Stepping up for the other side, you have more great coaches, like Charles Poliquin, who recommend pursuing a set until your spleen explodes! Their point is that to maximally stimulate muscle growth you need to create as much fatigue and damage to a muscle as possible. This is in accordance with the work of famed sport-scientist Vladimir Zatsiorsky who wrote that a muscle fiber that isn't fatigued during a set isn't being trained and thus won't be stimulated to grow. Taking a set to the point of muscle failure ensures that this set was as productive as it can be. Remember, simply recruiting a motor unit doesn't mean that it's been stimulated. To be stimulated, a muscle fiber must be recruited and fatigued (Zatsiorsky 1996). What about CNS fatigue? While it isn't the only cause of muscle failure, CNS overload isn't to be overlooked when talking about training to failure. The nervous system is the boss! It's the CNS that recruits the motor units, sets their firing rates, and ensures proper muscular coordination. Central fatigue can contribute to muscle failure, especially the depletion of the neurotransmitters dopamine and acetylcholine. A decrease in acetylcholine levels is associated with a decrease in the efficiency of the neuromuscular transmission. In other words, when acetylcholine levels are low, it's harder for your CNS to recruit motor units. So, if we look at the argument from this vantage point, we also have a catch-22. Stopping a set short of failure, while not worthless, might not provide maximal stimulation of the muscle fibers.

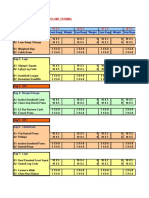

You might recruit them, but those that aren't being fatigued won't be maximally stimulated. However, if you go to failure, you'll ensure maximal stimulation from the set, but may cause CNS overload, which could hamper your long-term progress. So which one is it, really? If I want to grow as fast as possible should I go to failure or not? You should do both! In fact, going to failure or not should be an exercise-dependant variable. The more demanding an exercise is on the CNS, the farther away from failure you should stop the set. However, in exercises where the CNS is less involved, you should go to failure and possibly beyond. The following table shows when you should stop a set of an exercise: Type of Exercise CNS When to Stop the Set Involvement When the speed of movement decreases.

Olympic lifts, ballistic exercises, speed lifts with 45- Very high 55% of maximum, plyometrics, and jumps and bounds Deadlifts (and variations), goodmornings (and High variations), squats (and variations), lunges and stepups, free-weight pressing (overhead, incline, flat, decline, and dips), and free-weight/cable pulling (vertical and horizontal) Machine pressing and pulling, chest isolation work, Low quadriceps isolation work, hamstrings isolation work, lower back isolation work, and abdominal work Biceps isolation work, triceps isolation work, traps isolation work, calves isolation work, and forearms isolation work Very low

One to two reps short of failure. Accept some speed loss but don't go to failure.

Go to failure on at least one set per exercise; you can go to failure on all sets.

Go to failure on all sets. You can go past the point of failure (drop sets, rest/pause, etc.) on one to two sets per exercise.

Principle #2: Use the Best Exercises for Your Needs I'm letting the cat out of the bag: While big compound movements are the most effective overall mass-building exercises, isolation exercises aren't worthless. In some individuals, isolation work will be more effective at stimulating growth in specific muscles than the big basics. This is due to both mechanical and neural factors. Mechanical Factors

Some people aren't built for some compound lifts. For example, long-legged individuals aren't built for squatting. They won't be able to maximally stimulate lower body growth by only doing squats, front squats, and leg presses. They'll need a more thorough approach, including the use of isolation work like leg extensions and leg curls, as well as a lot of single limb work like lunges and Bulgarian split-squats. On the short side, those with stubby legs are built for squatting and can get complete lower body development simply by squatting. The same applies for other basic movements as well. The bottom line is that the less adapted your biomechanics are to a movement, the more secondary and isolation work you'll need to make the muscles involved grow. Neural Factors Due to muscle dominance, some people won't be able to optimally recruit a target muscle group during the execution of a compound movement. When you're doing an exercise, your body doesn't know that you're trying to make a certain muscle bigger. It only knows that a big ass weight is trying to crush you, and if you don't lift it, you'll cease to live! So to ensure you're around for the next issue of Playboy, your nervous system will shift the workload to the muscles better suited to do the job. If you're doing a bench press and you have overpowering deltoids and/or triceps, chances are your pectorals will receive little stimulation. Those individuals can get their bench press numbers sky high without actually building much of a chest. To get the pecs they want, they'll need to use more isolation work. However, those individuals with dominating pecs won't need much, if any, isolation work for that muscle group. As you can see, it's not a matter of compound being better than isolation (or vice versa). It's about finding the proper ratio of compound and isolation work that your body structure needs to grow. Everybody can gain a significant amount of overall muscle on their body by only working hard on compound movements. However, 90% of the population, if not more, will need to make proper use of isolation exercises to build a complete physique. If you're pressed for time, only doing the basic compound movements will get you 80% of the way toward a great physique. But if your goal is to be an aesthetic Adonis, you'll need isolation work to go that extra 20%. Principle #3: Keep Your Training Sessions Under 60 Minutes Cortisol is a stress hormone that's released during bouts of training. Some is needed, but too much cortisol, especially if it stays elevated after the training session, can greatly decrease muscle growth and strength improvements.

Cortisol is catabolic, meaning that it leads to the breakdown of stored substrates. During exercise, this can be useful since it'll breakdown stored glycogen into glucose and stored fat into fatty acids to provide energy for the working muscles. However, post-training it'll continue to breakdown glycogen which slows recovery. It also breaks down muscle tissue into amino acids, making it harder to add muscle mass. Furthermore, since both cortisol and Testosterone are both made from the same raw material (pregnenolone), constantly elevated cortisol levels will eventually lead to lower Testosterone levels. Cortisol output during training has been correlated with training volume; the more work being done during a session, the more cortisol is produced. This is especially true when metabolic-type training (high reps, short rest intervals) is used. To avoid overproducing cortisol, you want to keep your sessions short, around an hour or less. Another reason to avoid long sessions is related to mental focus. Regardless of how much you love training, at some point your focus will go in the crapper during a long session. The work performed in that state will be unproductive and could even lead to bad habits that'll screw you in the long run. You can train more than one hour per day, but split your daily volume into two workouts. In fact, splitting your daily workload into several shorter sessions is much more effective, as it leads to both lower cortisol production and higher Testosterone levels. It's been shown that when two daily sessions are used, Testosterone production is higher after the second workout than after the first. When training twice a day, it's best to train the same body part(s) during both workouts. I like to take this opportunity to train different types of contractions or goals on both occasions. For example: Option 1: Muscle Building Emphasis AM: Compound movements PM: Isolation work Option 2: Strength and Size Hybrid AM: Heavy lifting (2 to 6 reps) PM: Moderate loading (8 to 12 reps) Option 3: Muscle Building or Strength Emphasis (Depending on AM Load) AM: Concentric/regular lifting PM: Eccentric work

Option 4: Performance Training AM: Explosive lifting PM: Heavy lifting Option 5: Powerlifting or Olympic Lifting AM: Competition movement PM: Assistance work

It'd be a mistake to immediately jump to the maximum amount of training you can do with two-adays. There should be a progression toward that amount of training. Week 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Session 1 40 to 50 minutes 40 to 50 minutes 40 to 50 minutes 50 to 60 minutes 50 to 60 minutes 50 to 60 minutes 50 to 60 minutes 50 to 60 minutes Session 2 20 minutes 20 to 30 minutes 30 to 40 minutes None 20 to 30 minutes 30 to 40 minutes 40 to 50 minutes None

To judge if a workout was productive, but not excessive, look for three things: 1. At the end of the workout you're tired but not drained. 2. You feel a pump in the trained muscle. The intensity of the pump will obviously depend on the type of training that you did, but you should feel the muscles that were trained. 3. Two to three hours after the completion of the session you should yearn for more training. If you're still tired or lack motivation to train after this amount of time, chances are the session was excessive.

Principle #4: Contraction Type Depends on the Movement This goes hand-in-hand with the first principle mentioned. There are basically three ways of executing a movement when it comes to the speed of execution/type of contraction.

1. Constant tension movement: You never release the contraction of the target muscle group during the execution of the exercise. Basically, the muscle you're trying to stimulate must be kept maximally flexed for every inch of every rep of every set. Never let it relax, not even between each rep! The goal of this type of contraction is to prevent blood from entering the muscle during the set. This creates a hypoxic state because oxygen can't enter the muscle. It also prevents metabolic waste (lactate, hydrogen ions, etc.) from being taken out of the muscle during the set. Both of these factors increase the release of local growth factors like IGF-1, MGF, and growth hormone which will help stimulate growth. By the way, the use of isometric contractions also falls into this category. 2. Accelerative concentric, controlled eccentric: In this type of contraction, you're trying to accelerate during the actual lifting portion of the movement and lower the weight under control. You go to the exercise's full range of motion, but you briefly pause (around one second) between the stretch position and the following lifting action. This short pause will negate the contribution of the stretch-shortening cycle to the force production. You see, three things can contribute to producing force when you're lifting a weight: the actual contraction of the muscle, the activation of the reflex known as the stretch-shortening cycle (also called the myotatic stretch reflex), and the fact that muscle tissue is elastic, much like a rubber band. When trying to maximize the amount of actual work the muscle itself must perform, you want to minimize the action of both the stretch reflex and the elastic contribution of the muscle's structure. By doing a simple one-second pause before lifting the weight, you can accomplish that and thus maximize the amount of force that the muscle must produce. When you're lifting the weight, try to contract the muscle as fast as you can. This doesn't mean focusing on lifting the bar as fast as you can. Rather, it means that you should attempt to tense the muscle as hard as possible right from the start of the lifting motion. This will maximize the recruitment of the highly trainable fast-twitch fibers. Finally, when you lower the weight, do so under control. The eccentric portion of the movement is where most of the muscle damage occurs (micro-tears of the muscle fibers) and is a powerful growth stimulus. 3. Using the stretch reflex: With this type of lifting, you want to involve the stretch reflex and elastic component of the muscle. Thus, you want to lift the load as fast as possible. This explosive lifting will improve the capacity, over time, of the nervous system to recruit the fast-twitch fibers. It isn't effective by itself to stimulate maximum growth in those fibers because you can't fatigue them sufficiently (the time of contraction and duration of the muscle tension per rep is too low). But by lifting this way on some movements, you'll become better and better at activating the fast-

twitch fibers. When you're more efficient at doing that, every single other exercise becomes more effective. So, when do you use each technique? Every time you do an isolation exercise, use constant tension. Every time! The goal of an isolation exercise is to completely focus the stress on the target muscle. You want a maximal local effect, and to do that you need constant tension. Without constant tension, isolation exercises are pointless. This is actually one of the main reasons why isolation movements get a bad rap. People don't know how to do them properly, and as a result, they end up not being effective at stimulating growth. But when done using constant tension, they're very effective at it. Don't try to use constant tension lifting with compound movements. Not that it's impossible, but it's a waste of time. The goal of a compound movement is to overload several muscles. By nature, you can't isolate a muscle during a multi-joint exercise, and attempting to do so will make the exercise much less effective than it should be. With regular compound movements, you want to use the second technique: accelerative lifting, short pause in the stretch position, and a controlled eccentric. This will magnify the hypertrophic effect of the big movements by overloading the involved muscles as much as possible. Finally, the explosive lifting is best kept for exercises such as the Olympic lifts, plyometrics, and various jumping drills and throws. While these movements won't directly build mass, they'll improve your capacity to stimulate growth by improving your neural efficiency to recruit muscle fibers. Principle #5: Ideal Training Frequency Training frequency per body part is the "single-set vs. multiple sets" of this decade. In the late '70s and early '80s, the raging debate was between proponents of single-set training versus those who preferred the high volume approach. It was Arthur Jones vs. the Weiders; Mentzer against Arnold. The debate was never truly settled because, in some regards, both camps were right. But at the same time, neither of them were the indisputable truth. The fact is that both low and high volume training have their own pros and cons and can be used effectively given the right circumstances. The same can be said about training frequency. Just like with the volume debate, the frequency fisticuffs continue. I can guarantee you that one camp will never get to break out into "We Are the Champions" for the simple reason that both absolutist sides are right... and wrong! There's no such thing as a perfect training frequency per muscle group. Only optimal training frequency based on the other training variables, your lifestyle, and your recovery capacity. There

are, however, some broad guidelines that can be used to select the optimal training frequency that you need to use:

The harder you work a muscle group during a session, the longer it'll need to recover. If you typically perform super draining workouts (either via high volume or intensive methods), your training frequency per muscle group will need to be lower than if you don't kill the muscle every time you hit the gym. The more muscle damage you create in a session, the more recovery time you'll need before the trained muscle(s) can be hit hard again. Muscle damage is mostly a function of mechanical work and eccentric loading. Most damage occurs in the 8 to 12 reps per set range (or sets lasting 30 to 60 seconds with a heavy load). When the eccentric portion of the movement is emphasized (via slower eccentrics, accentuated eccentric methods, or eccentric-only training) the damage is also greater.

This is why Olympic lifters can train on the competition lifts six days a week. Olympic lifters rarely perform more than five reps per set, and the eccentric portion is all but eliminated because the bar is dropped to the floor at the end of every lift. Low mechanical work plus no eccentric equals the capacity to train the lifts extremely often.

Training frequency is also dependent on the level of nervous system fatigue that's induced during each training session. If you don't tire out the nervous system, you can obviously train more often. However, at some point the CNS must be challenged if it's to become more resilient. The more often you can stimulate a muscle without exceeding your capacity to recover, the more you'll progress. First, you must actually stimulate the muscles to grow. Sure, you can perform a few sets of easy exercises everyday (even several times a day), but if none of these "sessions" represent a challenge, there's no stimulation.

Then there's the aspect of exceeding your capacity to recover. You can be 100% convinced that super-high frequency training is the Holy Grail of muscle growth, but if you aren't allowing your body to recover, you simply won't progress! You must strike the perfect balance between stimulation and recovery to progress optimally. So what frequency do I recommend? Again, it's an individual thing. It depends on training style and what's going on outside of the gym (i.e. that thing called "life"). But, assuming you're training according to my new principles, the optimal training frequency per muscle group is two sessions every five to seven days. Those with a good recovery capacity or a stress-free life can aim for two sessions per muscle group every five to seven days. Individuals with an average recovery capacity or a more demanding life should shoot for two sessions every eight to ten days.

It isn't written in stone that every single muscle group has to be hit directly with this frequency. Indirect work (e.g. triceps getting some work when the chest is being trained) can also be factored in. If you're to hit each body part twice every five days, or in other words, using a three-day cycle with one day off, a good split looks like this: Day 1: Chest and back Day 2: Lower body Day 3: Arms and shoulders Day 4: Off Day 5: Repeat Or if you're more of an upper/lower kind of guy: Day 1: Lower body Day 2: Upper body Day 3: Trunk (abs and lower back) Day 4: Off Day 5: Repeat These two options are for those with a great recovery capacity and little life stress (you must have both going for you). If you have either a good recovery capacity or little stress then a six-day cycle will be a better option for you. You can go with any one of these three options: Day 1: Chest and back Day 2: Lower body Day 3: Off Day 4: Arms and shoulders Day 5: Off Day 6: Repeat Day 1: Lower body Day 2: Off Day 3: Upper body Day 4: Trunk (abs and lower back) Day 5: Off Day 6: Repeat Day 1: Whole body Day 2: Off Day 3: Lower body Day 4: Upper body

Day 5: Off Day 6: Repeat If you're average (or below) in your capacity to recover and/or your life is a mess, you should bump it up to a seven-day cycle. You then have these options: Day 1: Chest and back Day 2: Off Day 3: Lower body Day 4: Off Day 5: Arms and shoulders Day 6: Off Day 7: Repeat Day 1: Lower body Day 2: Off Day 3: Upper body Day 4: Off Day 5: Trunk (abs and lower back) Day 6: Off Day 7: Repeat Principle #7: Vary Your Training Often... But Not too Often! Rarely do you see someone changing their workout at an optimal frequency. They either change their workouts too often (the "I want to try that program I read about today" phenomenon) or not often enough (the "I can stay on the same routine longer than the same woman" phenomenon). Both of these knuckleheads have it wrong. If you don't change your program often enough, your body will fully adapt to it and as a result the workout won't represent a challenge anymore. When it stops being a challenge, there's no need for the body to adapt, change, and grow. If you change it too often, then you never actually give your body a chance to progress from a program. The one universal rule of gaining size or strength is progression. Every week you must become a bit better and work a little harder. But it's kind of hard to show progress when you never stick to a program for more than one week. As a rule of thumb, you should stick to a program for four to six weeks. After that, switch to a new one. There's no need to change every single training variable, though. Generally, the less progress you're making at the end of your current program, the more changes you should make on your next one.

Principle #8: Progression is the Real Key to Success The real secret to building muscle and strength is to progress. You must challenge your body on a consistent basis and find ways to progressively ask more of it. If you do the same thing over and over, you'll still look the same ten years from now. Now, there's more than one way to progress. What we're looking for are ways to make our bodies work harder. This is progress, and it's what'll lead to growth. Here are a few ways to make your body work harder. 1. Increase the load: You can challenge your body by adding weight to the bar and performing the same number of reps per set. For example, if you did 225 pounds for ten reps on the bench press last week and put up 230 for ten this week, you've forced your body to work harder. Obviously, this method of progression has its limitations. You can't just keep adding weight to the bar every week and expect your body to adapt. You'd increase your bench press by 260 pounds a year simply by adding five pounds to the bar per week if this were possible. Unfortunately, it's not. This first method of progression, while it can be used with any exercise, is better suited for compound movements. 2. Increase the reps: Another way to make your body work harder is to do more reps per set with the same weight. For example, if last week you did 225 for ten reps and this week you do 225 for 12 reps, you've progressed. Just like with the previous method, you can't add reps like this every week. 3. Increase the average weight lifted for an exercise: This is very similar to the first method, except whereas increasing the load refers to lifting more weight on your max set, this refers to lifting more weight on average for an exercise. Let's say you perform four sets of ten reps on the bench press: Week 1 Set 1: 200 pounds x 10 (2,000 pounds) Set 2: 210 pounds x 10 (2,100 pounds) Set 3: 220 pounds x 10 (2,200 pounds) Set 4: 225 pounds x 10 (2,250 pounds) Total weight lifted = 8,550 pounds Average weight per set = 2,137 pounds Average weight per rep = 213.7 pounds (214 pounds) Week 2

Set 1: 210 pounds x 10 (2,100 pounds) Set 2: 215 pounds x 10 (2,150 pounds) Set 3: 225 pounds x 10 (2,250 pounds) Set 4: 225 pounds x 10 (2,250 pounds) Total weight lifted = 8,750 pounds Average weight per set = 2,187 pounds Average weight per rep = 218.7 pounds (219 pounds) As you can see, even though the same top weight was reached during both workouts, on week two you lifted five pounds more on average. This is progression! 4. Increase training density: You can also progress by increasing the amount of work you perform per unit of time. This refers to decreasing the rest between sets while using the same weight. By reducing rest intervals, your body is forced to work harder and recruit more muscle fibers due to the cumulative fatigue phenomenon. This method of progression is better suited for either a fat loss program (in which case it can be used with any exercise) or isolation movements during a mass-gaining phase. 5. Increase training volume: This is probably the simplest progression method. If you want to make your body do more work, then do more work! This means adding sets for each muscle group. For example, on week one you might perform nine work sets for a muscle group and bump it to 12 on week two and 14 on week three.

While this can work, it shouldn't be abused, as it can lead to overtraining. Most trainees should stick to no more than 12 total sets per muscle group 90% of the time. 6. Use intensive training methods: The occasional inclusion of methods such as drop sets, rest/pause sets, tempo contrast, iso-dynamic contrast, supersets, and compound sets is another way of making your body work harder. It also shouldn't be abused, as it constitutes tremendous stress on the muscular and nervous systems. Furthermore, intensive methods, as we saw earlier, should be used to accomplish a specific purpose, not to trash the muscle for the sake of trashing it! 7. Use more challenging exercises: If you're used to doing all your training on machines, then move up to free weights. You'll force your body to work harder because you have to stabilize the load. If you use only isolation exercises and start including multi-joint movements, you'll also make your body work harder because of the intermuscular coordination factor. 8. Produce more tension in the targeted muscle group: It's one thing to lift the weight; it's another to lift it correctly in order to build size! As I often say, when training to build muscle, you're not lifting weights; you're contracting your muscles against a resistance. You can improve

the quality of your sets, thus making your body work harder, by always trying to flex the target muscle as hard as possible throughout the duration of each rep. This method should only be used with isolation exercises. 9. Increase the time under tension by lowering the weight under control: I'm not a huge fan of precise tempo recommendations, as I find that they can interfere with training concentration. However, when a muscle is under constant tension for a relatively longer period of time (45 to 70 seconds), more hypertrophy can be stimulated. The best way to do this without having to use less weight is to lower the weight even slower, while still focusing on tensing the muscles as hard as possible the whole time. 10. Increase the lifting speed: The concentric part of a strength training movement is where you're "lifting" the weight. In that phase of the contraction, the force formula applies: Force = Mass x Acceleration If you lift a certain weight with greater acceleration, you increase the amount of force you produce, thus making the set harder. It takes a lot more force to throw a baseball 50 yards than to throw it five feet. The weight is the same, but you must accelerate the ball more. More acceleration equals more force. This method of progression is best used for Olympic lifts, ballistic exercises, speed lifts, and the like. As you can see, there are several ways that you can use to improve the quality and demand of your workouts on a weekly basis. The more often you can progress, the more you'll grow, period!

You might also like

- Body For Life - Full BookDocument224 pagesBody For Life - Full Bookapi-370924497% (32)

- Strength Series 4 - Accumulation 7 - 5 X 3-5Document2 pagesStrength Series 4 - Accumulation 7 - 5 X 3-5denisNo ratings yet

- Thibaudeau's Guide To Hypertrophy-Clean Health Fitness InstituteDocument219 pagesThibaudeau's Guide To Hypertrophy-Clean Health Fitness InstituteVíctor Tarín100% (15)

- Free Glute WorkoutDocument12 pagesFree Glute Workoutxzx4vsxnhmNo ratings yet

- Picp Level 1 ManualDocument53 pagesPicp Level 1 ManualFélix Gouhier100% (2)

- Rugby Renegade WOD BibleDocument32 pagesRugby Renegade WOD BibleAgustin Garcia100% (2)

- Charles Poliquin - The Super Accumulation ProgramDocument6 pagesCharles Poliquin - The Super Accumulation ProgramAndrea100% (4)

- Christian Thibaudeau - Training The Three Types of ContractionsDocument12 pagesChristian Thibaudeau - Training The Three Types of ContractionsPeter Walid100% (4)

- Biosignature ModulationDocument3 pagesBiosignature ModulationMiguel Kennedy75% (4)

- Meso Endomorph Workout PlanDocument8 pagesMeso Endomorph Workout Planrtkiyous2947No ratings yet

- X TraordinaryArmsDocument55 pagesX TraordinaryArmsRicardo E Arrieta C100% (6)

- The List - Eric Falstrault - Strength SenseiDocument11 pagesThe List - Eric Falstrault - Strength SenseiJon shieldNo ratings yet

- Strength Senseis Pre Workout Nutrition PDFDocument49 pagesStrength Senseis Pre Workout Nutrition PDFFilip Velickovic100% (3)

- In-Season Training For MaintenanceDocument4 pagesIn-Season Training For MaintenancejapNo ratings yet

- Klatt Test Assesment Tool For Lower BodyDocument6 pagesKlatt Test Assesment Tool For Lower BodyEmiliano BezekNo ratings yet

- Muscle Fiber TestDocument4 pagesMuscle Fiber TestKamaruzaman Soeed100% (3)

- FinalDocument4 pagesFinalKang Kamalinder100% (1)

- Achieving Structural Balance - Upper Body PushDocument22 pagesAchieving Structural Balance - Upper Body Pushdjoiner45100% (5)

- Poliquin® International Certification ProgramDocument1 pagePoliquin® International Certification ProgramRajesh S VNo ratings yet

- A. Strength Qualities: Rep, Intensity & Training Effect RelationshipDocument10 pagesA. Strength Qualities: Rep, Intensity & Training Effect RelationshipQuốc Huy100% (6)

- Level 1 Workbook - Remedial Lifts-MinDocument4 pagesLevel 1 Workbook - Remedial Lifts-MinQuốc Huy100% (3)

- Poliquin PrinciplesDocument120 pagesPoliquin PrinciplesPauloCarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Popular Training Systems Adapted To Neurotype - Part 1 - German Volume Training - ThibarmyDocument25 pagesPopular Training Systems Adapted To Neurotype - Part 1 - German Volume Training - ThibarmyKomkor Guy100% (1)

- Book of Programmes for the Team Sport Athlete; Size & StrengthFrom EverandBook of Programmes for the Team Sport Athlete; Size & StrengthNo ratings yet

- Q A Charles PoliquinDocument106 pagesQ A Charles PoliquinMoosa Fadhel100% (3)

- Theory and Application of Modern Strength and Power Methods Modern MethodsDocument160 pagesTheory and Application of Modern Strength and Power Methods Modern Methodsicemn28100% (1)

- Hypertrophy Execution Mastery - Module 2 Workouts - Biceps & Triceps PDFDocument24 pagesHypertrophy Execution Mastery - Module 2 Workouts - Biceps & Triceps PDFMarvin100% (1)

- Tyler Kuntz Resignation LetterDocument3 pagesTyler Kuntz Resignation LetterKoby MichaelsNo ratings yet

- LSF 4 Week Booty IntensiveDocument35 pagesLSF 4 Week Booty IntensiveMargaridaFerreira100% (3)

- 2022 12 30 Website PDFDocument80 pages2022 12 30 Website PDFmostafakhafagy8100% (2)

- NEUROTYPINGDocument10 pagesNEUROTYPINGThibault AÏT-SAÏDNo ratings yet

- What Is Functional HypertrophyDocument7 pagesWhat Is Functional Hypertrophynima_44100% (1)

- Problem Solving Bench PressDocument66 pagesProblem Solving Bench Pressluis_tomaz100% (1)

- Thib Notes - Cluster ProgramingDocument4 pagesThib Notes - Cluster Programingdeclanku100% (1)

- Charles Poliquin - No Holds Barred Interview (2005)Document4 pagesCharles Poliquin - No Holds Barred Interview (2005)Alen_D100% (5)

- Muscle Fibre TestDocument3 pagesMuscle Fibre TestEduardo SantosNo ratings yet

- Zatsiorsky Intensity of Strength Training Fact and Theory Russ and Eastern Euro ApproachDocument20 pagesZatsiorsky Intensity of Strength Training Fact and Theory Russ and Eastern Euro ApproachJoão CasqueiroNo ratings yet

- Christian Thibaudeau - Shoulder Blasting Circuit CombosDocument1 pageChristian Thibaudeau - Shoulder Blasting Circuit CombosJTB01No ratings yet

- Building A Better Athlete With Functional Hypertrophy - Strength Sensei IncDocument5 pagesBuilding A Better Athlete With Functional Hypertrophy - Strength Sensei IncSean DrewNo ratings yet

- The Best Training Program Doesnt ExistDocument25 pagesThe Best Training Program Doesnt Existjap100% (2)

- Top Ten Nutrients That Support Fat Loss - Poliquin ArticleDocument4 pagesTop Ten Nutrients That Support Fat Loss - Poliquin Articledjoiner45No ratings yet

- Preventing Injuries in Arm Training - The Real Strength SenseiDocument8 pagesPreventing Injuries in Arm Training - The Real Strength SenseiSean DrewNo ratings yet

- Day 1: Chest/Back Sets/Reps Weight Sets/Reps Weight Sets/Reps Weight Sets/RepsDocument4 pagesDay 1: Chest/Back Sets/Reps Weight Sets/Reps Weight Sets/Reps Weight Sets/RepsPJ Burrows100% (2)

- Charles Poliquin - A Brief History of Periodization PDFDocument3 pagesCharles Poliquin - A Brief History of Periodization PDFJDredd0167% (3)

- Using The Force-Velocity Curve To Build Better Athletes - Elite FTS PDFDocument8 pagesUsing The Force-Velocity Curve To Build Better Athletes - Elite FTS PDFok okNo ratings yet

- Fat Loss Series 3 Intensification 6 Double Trisets PDFDocument2 pagesFat Loss Series 3 Intensification 6 Double Trisets PDFHolistic Body Marcin Michalski100% (1)

- Wave Ladders For Maximum StrengthDocument8 pagesWave Ladders For Maximum StrengthEduardo BonifacioNo ratings yet

- 6 Weeks To Great Abs - T NationDocument29 pages6 Weeks To Great Abs - T NationMamazaccoRacerpoilNo ratings yet

- Bio Signature Womens FitnessDocument1 pageBio Signature Womens Fitnessnick5134No ratings yet

- Judd LoganDocument4 pagesJudd LoganShawn SchraufnagelNo ratings yet

- The Benefits of BCAAs - Poliquin ArticleDocument8 pagesThe Benefits of BCAAs - Poliquin Articlecrespo100% (2)

- Functional Hypertrophy - Phase 2-Day 1 Chest & Back: Exercise Cycle Sets Reps Tempo Rest W/R W/R W/R W/RDocument3 pagesFunctional Hypertrophy - Phase 2-Day 1 Chest & Back: Exercise Cycle Sets Reps Tempo Rest W/R W/R W/R W/RNeetu Kang100% (3)

- Training - Principles - The Science of Tempo and Time Under Tension PDFDocument10 pagesTraining - Principles - The Science of Tempo and Time Under Tension PDFFernando Simao Victoi100% (1)

- How To Lift For Maximal Hypertrophy: Free ResourceDocument10 pagesHow To Lift For Maximal Hypertrophy: Free Resourcebaris arslanoglu100% (2)

- Chris Thibaudeau. 9 Ways To Keep Getting BetterDocument2 pagesChris Thibaudeau. 9 Ways To Keep Getting BetterPaolo Altoé100% (1)

- Isometrics The Most Underrated Training Tool ThibarmyDocument6 pagesIsometrics The Most Underrated Training Tool Thibarmynounou100% (2)

- Thibarmy - Five Quick Tips For Better AbsDocument3 pagesThibarmy - Five Quick Tips For Better AbsAnn Petrova0% (1)

- Ep 52 Charles Poliquin - Training Methods Part 1: Listen To This Podcast Episode HereDocument29 pagesEp 52 Charles Poliquin - Training Methods Part 1: Listen To This Podcast Episode HereLukas100% (1)

- The Alternating Conjugate Periodization ModelDocument9 pagesThe Alternating Conjugate Periodization ModelJordanKruegerNo ratings yet

- Twelve Week Training Program - DEADLIFTS - Article - Poliquin MobileDocument5 pagesTwelve Week Training Program - DEADLIFTS - Article - Poliquin MobileJon shieldNo ratings yet

- 6 Page - POLIQUIN INTERNATIONAL CERTIFICATION PROGRAM Performance Specialization Level 1Document6 pages6 Page - POLIQUIN INTERNATIONAL CERTIFICATION PROGRAM Performance Specialization Level 1nam nguyenNo ratings yet

- Shoulder Savers PDFDocument5 pagesShoulder Savers PDFlunn100% (6)

- 10 X 10 PoliquinDocument3 pages10 X 10 PoliquinSergio Ramos Ustio100% (2)

- Charles Poliquin-The Super-Accumulation Program - T NationDocument6 pagesCharles Poliquin-The Super-Accumulation Program - T NationManuel Ferreira PT100% (3)

- Advanced Training Techniques - FREE EBOOKDocument33 pagesAdvanced Training Techniques - FREE EBOOKCláudio Milane De OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Hamstring Paradigm: Train Hamstrings Both As Knee Flexors and Hip ExtensorsDocument5 pagesHamstring Paradigm: Train Hamstrings Both As Knee Flexors and Hip ExtensorsSaltForkNo ratings yet

- Bodybuilding Training SystemsDocument5 pagesBodybuilding Training Systemskamak777750% (2)

- Neurotypes and Fighting Styles - Christian Thibaudeau Coaching - Forums - T NationDocument3 pagesNeurotypes and Fighting Styles - Christian Thibaudeau Coaching - Forums - T NationVladimir OlefirenkoNo ratings yet

- Universidad Del IstmoDocument3 pagesUniversidad Del IstmoRicardo E Arrieta CNo ratings yet

- BeyondX RepDocument114 pagesBeyondX RepRicardo E Arrieta C100% (1)

- The Massive Growth SystemDocument273 pagesThe Massive Growth SystemalaberhtNo ratings yet

- Peachplease Gym Week1 1Document14 pagesPeachplease Gym Week1 1TejaRejc100% (1)

- Tracker Sheet: Full Body Burn AdvancedDocument1 pageTracker Sheet: Full Body Burn AdvancedddsNo ratings yet

- Proper Etiquette in A Fitness FacilityDocument3 pagesProper Etiquette in A Fitness FacilityMartin RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Lean Eating For Women - Fourth Phase (4 Weeks) : They're Not Called Weights Because They're LightDocument26 pagesLean Eating For Women - Fourth Phase (4 Weeks) : They're Not Called Weights Because They're LightĐạt NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Tracy's Swing ProgressionsDocument4 pagesTracy's Swing ProgressionsPicklehead McSpazatronNo ratings yet

- Dumbbellonly 0 PDFDocument1 pageDumbbellonly 0 PDFamerican2300No ratings yet

- UEX Back-Tricep Workout PDFDocument7 pagesUEX Back-Tricep Workout PDF10 Chandra Prakash Pandian PNo ratings yet

- A History of The Bench PressDocument2 pagesA History of The Bench Presslw98No ratings yet

- StretchingDocument38 pagesStretchingVennia Papadipoulou40% (15)

- The "Spartacus" Workout 3 Day Circuit TrainingDocument3 pagesThe "Spartacus" Workout 3 Day Circuit TrainingNatali KruNo ratings yet

- Be A Hero Fitness - Baki The Grappler Mass Workout - Here We Are.. - PDFDocument1 pageBe A Hero Fitness - Baki The Grappler Mass Workout - Here We Are.. - PDFAndres Diego100% (1)

- FLEXIBILITY and STRETCHING EXERCISES PDFDocument3 pagesFLEXIBILITY and STRETCHING EXERCISES PDFRubamoNo ratings yet

- Physical Assessment Tools For To and Through Selection - Stew Smith FitnessDocument14 pagesPhysical Assessment Tools For To and Through Selection - Stew Smith FitnesscallenNo ratings yet

- Three Muscle Toning Arm Workouts For Women - Muscle & Strength PDFDocument7 pagesThree Muscle Toning Arm Workouts For Women - Muscle & Strength PDFAliNo ratings yet

- Greg Nuckols 28 Programs by StrengtheoryDocument78 pagesGreg Nuckols 28 Programs by StrengtheoryThe ChampNo ratings yet

- The Brazilian Butt Ebook1Document72 pagesThe Brazilian Butt Ebook1Camden White57% (14)

- Effect of Hamstring Emphasized Resistance Training On H-Q Strength RatioDocument7 pagesEffect of Hamstring Emphasized Resistance Training On H-Q Strength RatioRaja Nurul JannatNo ratings yet

- NCC - NCX (11 7 22)Document1 pageNCC - NCX (11 7 22)azizNo ratings yet

- Gym Plan: Week 1: Full-Body SplitDocument9 pagesGym Plan: Week 1: Full-Body SplitSalih MohayaddinNo ratings yet

- The 12 Untapped Targets To Ignite New Muscle GrowthDocument68 pagesThe 12 Untapped Targets To Ignite New Muscle Growthace_mimNo ratings yet

- Interval Training Workouts Build Speed and EnduranceDocument2 pagesInterval Training Workouts Build Speed and EndurancenewrainNo ratings yet

- HurdlesDocument4 pagesHurdlesapi-313469173No ratings yet

- 2017 National Poomsae GroundrulesDocument7 pages2017 National Poomsae GroundrulesEljan VentureNo ratings yet

- Australian Ironman Magazine July 2016 PDFDocument140 pagesAustralian Ironman Magazine July 2016 PDFgeorgeNo ratings yet