Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Er It Ro Leukoplakia

Er It Ro Leukoplakia

Uploaded by

Firma Nurdinia DewiOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Er It Ro Leukoplakia

Er It Ro Leukoplakia

Uploaded by

Firma Nurdinia DewiCopyright:

Available Formats

Pediatric Dermatology Vol. 26 No.

2 176179, 2009

Dyskeratosis Congenita Report of a Case with Emphasis on Gingival Aspects

Silvia V. Lourenc o, D.D.S., Ph.D.,* Paula A. Boggio, M.D., Fernando A. Fezzi, D.D.S., o, D.D.S., and Marcello Menta S. Nico, M.D., Ph.D. Alexandre L. Sebastia

*Department of General Pathology, Dental School, University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil, Department of Dermatology, Hospital das Clnicas, Medical School, University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil

Abstract: A case of dyskeratosis congenita (DC) of an 11-year-old male is reported. He presented with the characteristic clinical triad of reticular pigmentation of the skin, dystrophic nails and oral lesions, and up to the present he had not developed hematological compromise. Oral lesions consisted of extensive tongue erosions and keratosis, and exuberant gingivitis associated. Appropriate periodontal treatment was performed with discrete improvement only. We emphasize that severe gingival inammation, although infrequent, may represent an alteration specic to DC and therefore should be considered as an additional sign of this syndrome.

Dyskeratosis congenita (DC) is a rare inherited disorder with variable mode of inheritance, which mainly involves ectodermal derived tissues. It was rst described by Zinsser in 1910 and later redened by Engman and Cole (1). It is characterized by the dermatologic triad of reticulated skin pigmentation, mucosal lesions, and nail dystrophy. Several associated abnormalities are reported in DC, as well as predisposition to malignancy (13). Complications include bone marrow failure of unclear physiopathology and malignant neoplasms, which constitute the primary cause of death in the second and third decades of life (13). We herein report a case of DC of an 11-year-old male, who presented the typical dermatologic features of the disease. Additionally, a severe gingivitis was detected and that may constitute a rare and probably underreported oral nding related to this condition.

Address correspondence to Dr. Silvia Vanessa Lourenc o, D.D.S., Ph.D., Faculdade de Odontologia da Universidade de Sa o Paulo, Disciplina de Patologia Geral, Av Prof Lineu Prestes, 2227, ria, Sa CEP: 05508-000, Cidade Universita o Paulo, SP-Brazil, or e-mail: sloducca@usp.br. DOI: 10.1111/j.1525-1470.2009.00878.x

CASE REPORT An 11-year-old Afro-Brazilian man was referred with a 2-year history of a painful plaque on the tongue. Oral examination showed a keratotic, atrophic, and partially eroded plaque extending form the dorsum to the right lateral border of the tongue (Fig. 1). Physical examination revealed subtle reticulated hyperpigmented macules with mild atrophy, symmetrically distributed on eyelids, face (Fig. 2A), neck (Fig. 2B), upper chest, extensor aspects of the arms, axilla, and penis and groin (Fig. 2C). Severe 20-nail-dystrophy was also observed (Fig. 3). Both skin and nail lesions appeared approximately at 7 years of age. Personal data was otherwise irrelevant, and familiar history was noncontributory (examination of his parents revealed no abnormalities). A biopsy specimen from the tongue lesion revealed moderate

176

2009 The Authors. Journal compilation 2009 Wiley Periodicals, Inc.

Lourenc o et al: Gingivitis in Dyskeratosis Congenita

177

Figure 1. Eritroleukoplakic plaque on the dorsum of the tongue.

Figure 3. Severe ngernails dystrophy.

epithelial dysplasia (Figs. 4A and B). A diagnosis of DC was rendered with the compilation of dermatological and oral signs. During follow-up he developed severe edema and erythema of the upper and lower gingivae, associated with erosion and hypertrophy (Fig. 5A). Biopsy from aected gingiva was performed, which showed nonspecic diuse chronic inammation (Fig. 5B). Appropriate periodontal treatment was initiated with only slight improvement after several sessions. Hematological evaluation of the patient revealed mild anemia with macrocytosis and poikylocytosis on peripheral smear. A bone marrow aspirate and biopsy were performed and a hypercellular marrow with diminished granulocyte erythroblast relationship was

detected. Relative hypocellularity of granulocytic series with larger granulocytes, and absolute and relative hypercellularity of erythroid series with macroerythroblasts, some of them showing karyolysis and karyorrhexis were also seen. Remaining cellular series as well as interstitial elements presented no abnormalities. The patient persisted under continuous surveillance, and as a moderate pancytopenia was recently detected, bone marrow transplantation was scheduled. DISCUSSION Dyskeratosis congenita, also known as ZinsserEngman-Cole syndrome, is an inherited severe multisystemic disorder that mainly aects tissues of

2A

Figure 2. Reticulated pigmented macules on eyelids and cheeks (A), neck (B), and penis and groin (C).

178 Pediatric Dermatology Vol. 26 No. 2 March April 2009

Figure 4. Tongue epithelial moderate dysplasia. HematoxylinEosin, original magnication 40 (A), and 100 (B).

Figure 5. Erythema and edema of upper gingiva (A), and nonspecic chronic inammatory inltrate on gingival biopsy (HematoxylinEosin, original magnication 40) (B).

ectodermal origin (1). It is an extremely rare conditionwith an estimated prevalence under one per million, widely distributed, and aecting all races (24). Three dierent modes of inheritance are currently recognized: recessive X-link DC (OMIM 305000) autosomal dominant DC (OMIM 127550) and autosomal dominant DC (OMIM 224230). Most reported cases correspond to recessive X-link transmission, generally aecting men (5). Dyskeratosis congenita pathogenesis is linked to an impairment of telomerase maintenance. Telomeres are specialized nucleoprotein structures at the end of chromosomes that protect end-to-end chromosome fusion. Telomeres get shorter with each cell division because DNA polymerase-I cannot copy the extreme end of a DNA strand, therefore when telomeres get critically short, cell death occurs. Telomerase activity counteracts the continuous telomere shortening caused by cell replication. Telomerase activity is not observed after birth in most somatic cells. In contrast, germ cells, stem cells, activated T-cells, monocytes, and notably most cancer cells express telomerase activity, but only in germ cells

and cancer cells is telomerase activity sucient to prevent telomere shortening (5). Mutations in three genes have been identied in patients with DC-DKC1, TERC, and TERT. The products of these genes, dyskerin encoded by DKCI, the RNA component of telomerase, TERC, and the catalytic component of telomerase, TERT, form the catalytically active telomerase. DKC1 maps to the X-chromosome. Mutations in this gene cause X-linked DC in all male members of aected families and carrier state in females. In families with DC because of TERC or TERT gene mutations the disease usually follows an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance. Patients with the autosomal dominant form typically present with milder disease and the onset of their manifestations is often later in life (5). Despite genetic heterogeneity, DC phenotypes are usually similar. Nevertheless, some data suggest a milder clinical course, with late diagnosis and a lesser incidence of aplastic anemia in patients with autosomal dominant inheritance (13). In the present case X-linked recessive inheritance is likely, as there is no

Lourenc o et al: Gingivitis in Dyskeratosis Congenita

179

other family member aected and familial consanguinity was denied. Dyskeratosis congenita rst signs are detected between the ages of 5 to 12 years with dermatologic alterations. The triad of reticulated skin pigmentation, mucosal lesions, and nail dystrophy typically characterizes the syndrome. A lacy reticulated brown pigmentation sometimes with superimposed discrete atrophy and telangiectases (leading to a poikilodermatous aspect) overlying the skin of face, neck, chest, proximal limbs and intertriginous areas, is frequently the rst sign of DC. Nail compromise, ranging from mild dystrophy to petirigum or anonichya, is generally present concurrently (14). Mucosal alterations occur simultaneously with oral cavity compromise being a rule. Initial lesions are recurrent vesicles and erosions, followed by white keratotic patches that evolve to erythroplakia with recurrent episodes of ulceration. Although oral lesions can occur at dierent sites, the dorsum of the tongue is the site more frequently aected (3,4,6,7). Ulceration without tendency to heal, inltration or progressive enlargement of oral mucosal lesions must be suspicious of evolution into a squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The case reported herein presented with the complete triad of DC, referring the rst signs as skin and nail alterations at the age of 7 years and posterior development of leukoplakia of the tongue at 9, without complication up to date. Less common oral ndings in DC include diuse mucosal pigmentation and gingival compromisewith bleeding, recession, with or without inammation (6,7). Severe gingivitis, as observed in our patient, is an extremely infrequent occurrence in DC that should probably be recognized as specic to the disease. This manifestation was reported by some authors as a condition that resembled juvenile periodontitis (6,7). The absence of improvement after periodontal treatment supports this hypothesis. Dental ndings on DC comprise of caries formation, hypondontia, hypocalcication, thin enamel structure, increased mobility and loss of teeth elements, short blunted roots, taurodontism, destruction of alveolar margins and severe alveolar bone loss resembling juvenile periodontitis, but these were not present in our patient (6,7). Systemic manifestations of DC (a few of which seem to be regarded to ectodermal defect) are present with variable frequency, and consist of growth and mental retardation, deafness, transparent tympanic membranes, lacrimal duct obstruction, conjunctivitis, blepharitis, palmoplantar hyperkeratosis and hyperhidrosis, urethral anomalies, esophageal stenosis, choanal atresia, hepatic abnormalities, frontal lobes atrophy, extensive intracranial calcications, hypogonadism, osteoporosis,

avascular necrosis of bone and immunological disturbances (1,69). Multidisciplinary evaluation of our patient did not detect any of these alterations. Approaching the second or third decades of life almost 50% of DC patients will develop bone marrow failure, manifesting as aplastic anemia or pancytopenia (14). Therefore, every DC patient should be under continuous hematological surveillance that allows, as in the present case, an early diagnosis and introduction of specic therapy for bone marrow failure. An increased incidence of malignancies constitutes another constant feature of DC, being cutaneous or mucosal SCC, esophageal and pancreatic carcinomas and Hodgkin lymphoma the most frequent tumors associated with the syndrome. Squamous cell carcinomas often develop on previously aected mucosal areas, between the third and fth decades, so permanent monitoring is highly recommended (4,9,10). Complications of bone marrow insuciency, together with malignancies are the principal cause of death in DC patients, which occurs at an average age of 23.6 to 30 years (2,10). AKNOWLEDGMENT The study was supported by FAPESP grant 02 02676-7. REFERENCES

1. Baselga E, Drolet BA, van Tuinen P et al. Dyskeratosis congenita with linear areas of severe cutaneous involvement. Am J Med Genet 1998;75:492496. 2. Shay JW, Wright WE. Telomeres in dyskeratosis congenita. Nat Genet 2004;36:437438. 3. Brown CJ. Dyskeratosis congenita: report of a case. Int J Paediatr Dent 2000;10:328334. 4. Handley TP, McCaul JA, Odgen GR. Dyskeratosis congenita. Oral Oncol 2006;42:331334. 5. Bessler M, Du HY, Gu B et al. Dysfunctional telomeres and dyskeratosis congenita. Haematologica 2007;92:1009 1012. 6. Yavuzyilmaz E, Yamalik N, Yetgin S et al. Oral-dental ndings in dyskeratosis congenita. J Oral Pathol Med 1992;21:280284. 7. Wald C, Diner H. Dyskeratosis congenita with associated periodontal disease. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1974;37:736744. 8. Lener EV, Tom WL, Cunningham BB. Dyskeratosis congenita in an adolescent girl with associated choanal atresia. Pediatr Dermatol 2005;22:3135. 9. Knudson M, Kulkarni S, Ballas ZK et al. Association of immune abnormalities with telomere shortening in autosomal-dominant dyskeratosis congenita. Blood 2005; 105:682688. 10. Baykal C, Kavak A, Gulcan P et al. Dyskeratosis congenita associated with three malignancies. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2003;17:216218.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- House Bill15090 TranscriptDocument3 pagesHouse Bill15090 Transcriptlifeis6100% (4)

- Animal Physiology Test Bank Chapter 24Document24 pagesAnimal Physiology Test Bank Chapter 24rk100% (6)

- Iron Kinetics and Laboratory AssessmentDocument4 pagesIron Kinetics and Laboratory AssessmentJohnree A. EvangelistaNo ratings yet

- NEB mRNA Lisolation ManualDocument9 pagesNEB mRNA Lisolation Manual10sgNo ratings yet

- Phenylketonuria (PKU) : PH Arn, Nemours Children's Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USADocument3 pagesPhenylketonuria (PKU) : PH Arn, Nemours Children's Clinic, Jacksonville, FL, USAHappy612No ratings yet

- A New Modified Tandem Appliance For Management of Developing Class III MalocclusionDocument5 pagesA New Modified Tandem Appliance For Management of Developing Class III MalocclusionFirma Nurdinia DewiNo ratings yet

- Catlan's ApplianceDocument5 pagesCatlan's ApplianceFirma Nurdinia DewiNo ratings yet

- 3mix MPDocument6 pages3mix MPFirma Nurdinia DewiNo ratings yet

- "3Mix-MP in Endodontics - An Overview": Varalakshmi R Parasuraman MDS, Banker Sharadchandra Muljibhai MDSDocument10 pages"3Mix-MP in Endodontics - An Overview": Varalakshmi R Parasuraman MDS, Banker Sharadchandra Muljibhai MDSFirma Nurdinia DewiNo ratings yet

- OrthodonticDocument3 pagesOrthodonticFirma Nurdinia DewiNo ratings yet

- Non-Surgical Treatment of Periapical Lesion Using Calcium Hydroxide-A Case ReportDocument4 pagesNon-Surgical Treatment of Periapical Lesion Using Calcium Hydroxide-A Case ReportNadya PurwantyNo ratings yet

- Periodontal Host Modulation With Antiproteinase Anti Inflammatory and Bone Sparing AgentsDocument26 pagesPeriodontal Host Modulation With Antiproteinase Anti Inflammatory and Bone Sparing AgentsVrushali BhoirNo ratings yet

- Implementing Sandwich Technique With RMGI: (Resin-Modified Glass-Ionomer)Document8 pagesImplementing Sandwich Technique With RMGI: (Resin-Modified Glass-Ionomer)Firma Nurdinia DewiNo ratings yet

- Using Magnets To Increase Retention of Lower DentureDocument4 pagesUsing Magnets To Increase Retention of Lower DentureFirma Nurdinia DewiNo ratings yet

- Application of The Double Laminated Technique in Restoring Cervical LesionsDocument4 pagesApplication of The Double Laminated Technique in Restoring Cervical LesionsFirma Nurdinia DewiNo ratings yet

- Host Modulation in PeriodonticsDocument12 pagesHost Modulation in PeriodonticsFirma Nurdinia DewiNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0168827823050584Document22 pagesPi Is 0168827823050584khuyennguyenhmu080692No ratings yet

- Deformaciones FlexuralesDocument11 pagesDeformaciones FlexuralesCamila BragagniniNo ratings yet

- Biomechanical Management of Children and Adolescents With Down SyndromeDocument8 pagesBiomechanical Management of Children and Adolescents With Down SyndromeMihaela NițulescuNo ratings yet

- 2 Mic125Document7 pages2 Mic125nadiazkiNo ratings yet

- PSY 103 Class NotesDocument16 pagesPSY 103 Class NotesNerdy Notes Inc.100% (3)

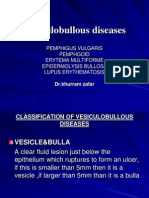

- Vesiculobullous DiseasesDocument48 pagesVesiculobullous DiseasesAprilian PratamaNo ratings yet

- Birth DefectsDocument36 pagesBirth DefectsSohera NadeemNo ratings yet

- Reviews: DNA Methylation Profiling in The Clinic: Applications and ChallengesDocument14 pagesReviews: DNA Methylation Profiling in The Clinic: Applications and ChallengesVivi ZhouNo ratings yet

- Hormonal Control of GitDocument42 pagesHormonal Control of GitM. Shahin Uddin KazemNo ratings yet

- Task 3B: (Example) 0. Why Have People in Britain Lost Their Trust in The Food Industry?Document2 pagesTask 3B: (Example) 0. Why Have People in Britain Lost Their Trust in The Food Industry?marNo ratings yet

- Ultrasound of Congenital Fetal Anomalies: Differential Diagnosis and Prognostic Indicators. Second EditionDocument30 pagesUltrasound of Congenital Fetal Anomalies: Differential Diagnosis and Prognostic Indicators. Second EditionDevanshNo ratings yet

- NAW Anthology 2013Document164 pagesNAW Anthology 2013NirbhaiNo ratings yet

- Imaging Protocol HandbookDocument90 pagesImaging Protocol HandbookAnita SzűcsNo ratings yet

- BIOPIRACYDocument9 pagesBIOPIRACYiansolanoyu100% (1)

- Chapter 7. The Thyroid Gland: David S. Cooper, MD Paul W. Ladenson, MA (Oxon.), MDDocument2 pagesChapter 7. The Thyroid Gland: David S. Cooper, MD Paul W. Ladenson, MA (Oxon.), MDruthagneNo ratings yet

- Biostatistics 140127003954 Phpapp02Document47 pagesBiostatistics 140127003954 Phpapp02Nitya KrishnaNo ratings yet

- PheoDocument4 pagesPheoantonijevicuNo ratings yet

- Sohail Et Al 2023 NatureDocument28 pagesSohail Et Al 2023 NatureKerry Atón RosalanoNo ratings yet

- Chromosomal AberrationsDocument17 pagesChromosomal AberrationsHajiRab NawazNo ratings yet

- Nature 20120329Document210 pagesNature 20120329mdash1968No ratings yet

- Marchant Genetics in Toxic Tort Litigation 2016Document10 pagesMarchant Genetics in Toxic Tort Litigation 2016Kirk HartleyNo ratings yet

- DiGeorge Syndrome (DGS)Document11 pagesDiGeorge Syndrome (DGS)Saba Parvin Haque100% (1)

- AP Biology Unit 2 Cells ReviewDocument2 pagesAP Biology Unit 2 Cells ReviewPhilly CheungNo ratings yet

- Contents of The 10 KumainmentsDocument9 pagesContents of The 10 KumainmentsZennon Blaze ArceusNo ratings yet

- Dr. Agtuca - BT, CT, PT & PTTDocument31 pagesDr. Agtuca - BT, CT, PT & PTTJino BugnaNo ratings yet