Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Analysing Narratives As Practices

Analysing Narratives As Practices

Uploaded by

Abhijeet GuptaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Analysing Narratives As Practices

Analysing Narratives As Practices

Uploaded by

Abhijeet GuptaCopyright:

Available Formats

Qualitative Research

http://qrj.sagepub.com Analysing narratives as practices

Anna De Fina and Alexandra Georgakopoulou Qualitative Research 2008; 8; 379 DOI: 10.1177/1468794106093634 The online version of this article can be found at: http://qrj.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/8/3/379

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Qualitative Research can be found at: Email Alerts: http://qrj.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://qrj.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav Citations http://qrj.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/8/3/379

Downloaded from http://qrj.sagepub.com by RAJESH SINHA on April 27, 2009

A RT I C L E

Analysing narratives as practices

Q R

379

ANNA DE FINA Georgetown University, USA A L E X A N D R A G E O RG A KO P O U L O U Kings College London, UK

Qualitative Research Copyright 2008 SAGE Publications (Los Angeles, London, New Delhi and Singapore) vol. 8(3) 379387

ABSTRACT

Departing from a critique of the conventional paradigm of narrative analysis, inspired by Labov and the narrative turn in social sciences, we propose an alternative framework, recommending combining a focus on the local occasioning of narratives in interaction with the analysis of their participation in a variety of macro-processes, through mobilizing the notions of social practice, genre and community of practice. community of practice, genre, narrative analysis, small stories, social practice

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Within narrative analysis, there are debates around two different ways of defining and doing narrative: one inspired by a conventional and largely canonical paradigm; the other, based on an interactionally focused view of narrative. We draw on this dialogue to articulate an alternative approach, which we call the social interactional approach (henceforth SIA). This encompasses a view of narrative as talk-in-interaction and as social practice, teasing out the analysis of interaction as a fundamental aspect of any study of narrative, and the investigation of the intimate links of narrative-interactional processes with larger social processes as a prerequisite for socially minded research. What we are calling the conventional paradigm was inspired by Labov and Waletzkys (1967) foundational model of narrative analysis, but also by assumptions about the role and nature of narrative as an archetypal mode of communication derived from the narrative turn in the social sciences. Notably, Labov and Waletzky (1967: 13) defined narrative in functional terms as one verbal technique for recapitulating past experience, in particular a technique of constructing narrative units which match the temporal sequence of that experience. In their model, a narrative text was characterized in structural terms through the presence of temporal ordering between event clauses, and

DOI: 10.1177/1468794106093634

Downloaded from http://qrj.sagepub.com by RAJESH SINHA on April 27, 2009

380

Qualitative Research 8(3)

through its organization into structural components (such as complicating action and resolution). Evaluation (i.e. the expression of the narrators point of view on the events) was postulated as a structural component and a diffuse mechanism for conveying a story point. Labov and Waletzkys model was based on stories told in interviews and, in principle, was meant as a description of narratives of personal experience, not all types of narratives. That said, it has had a profound influence in narrative work and paved the way for seeing narrative as a privileged site for the study of a wide range of aspects relevant to the study of language in society (see contributions in Bamberg, 1997). The frequent use of the Labovian approach as the basis of empirical studies has had profound implications for the direction of narrative analysis, creating notions of a narrative canon and orthodoxy, i.e. presuppositions on what constitutes a story, a good story, a story worth analysing, etc., that have in turn dictated a specific analytic vocabulary and an interpretive idiom. More specifically, Labovs structural definition of narrative has resulted in a tendency to recognize as narratives only texts that appear to be well organized, with a beginning, a middle and an end, that are teller-led and largely monological, and that occur as responses to (an interviewers) questions. In addition, his focus on story point and evaluation has inadvertently privileged the teller as the main producer of meaning. Finally, his reliance on interview data has led to the neglect of the role of the storytelling activity in the local context in which it is generated. Labovs model coincided with, and surely benefited from, the insights of the narrative turn in social sciences. Since then, studies of autobiographical narratives that have focused on the construction of identity have proliferated. There is, however, a tendency to see narrative as a fundamental mode for constructing realities and so as a privileged structure/system/mode for tapping into identities, particularly constructions of self (for a critique, see Georgakopoulou, 2006a). The guiding assumption has thus been that, by bringing the coordinates of time, space and personhood into a unitary frame, narrative can afford a point of entry into the sources behind these representations (such as author, teller and narrator), and that it can make them empirically visible for analytical scrutiny in the form of identity analysis.1 These two trends together, Labovian narrative analysis and identity focused approaches related to the narrative turn, have informed what we have labeled here as the conventional paradigm for narrative analysis. The stories that have been marginalized or excluded from this paradigm are those that do not conform to the schema of an active teller, highly tellable account, relatively detached from surrounding talk and activity, linear temporal and causal organization, and certain, constant moral stance (Ochs and Capps, 2001: 20). Put differently, the neglected stories include a gamut of under-represented narrative activities, such as tellings of ongoing events, future or hypothetical events, shared (known) events, but also allusions to tellings, deferrals of tellings, and refusals to tell (Georgakopoulou, 2006b: 130). Alongside the privileging of a

Downloaded from http://qrj.sagepub.com by RAJESH SINHA on April 27, 2009

De Fina and Georgakopoulou: Analysing narratives as practices

381

specific type of narrative (and partly because of that), the impact of different aspects of a storytelling event (such as time, place, relations between interlocutors, events in which the storytelling is inserted, salient topics discussed before and after the narrative, etc.) has been downplayed, as have narrative interactional dynamics (such as telling roles and telling rights, audience reactions, etc.).

Narrative as talk-in-interaction

Important challenges to the methodological tendencies and assumptions of conventional narrative analysis have been derived from research on conversational storytelling, most of which broadly aligns itself with Conversation Analysis (henceforth CA). The main premise of the CA critique is the idea that (oral) narrative in any context is and should be explicitly seen as talkin-interaction. Narrative is an embedded unit, enmeshed in local business, not free-standing or detached/detachable. Viewing narratives as more or less self-contained texts that can be abstracted from their original context of occurrence thus misses the fact that both the telling of a story, and the ways in which it is told, are shaped by previous talk and action. A related premise of CA is that recognizing structure in narrative cannot be disassociated from an engagement with surrounding discourse activity, and some kind of development and an exit (Sacks, 1974; Jefferson, 1978). As such, narratives are sequentially managed; their tellings unfold on-line, moment-by-moment in the here-and-now of interactions. Thus, they can be expected to raise different types of action and tasks for different interlocutors (Goodwin, 1984). This brings into sharp focus the need to distinguish between different participant roles while moving beyond the restrictive dyadic scheme of teller-listener. The exploration of co-construction is at the heart of our SIA. The story recipients, far from being a passive audience, may reject, modify, or under-cut tellings and narrative points (Goodwin, 1984; Goodwin, 1986; Cedeborg and Aronsson, 1994; Ochs and Capps, 2001); they may be instrumental in how the teller designs their story in the first place, particularly in cases in which there are differentiated roles among storytelling participants (e.g. some may know of the events of the story, others not, some may be characters in the story, etc.) that have to be managed through the storytelling process. As this suggests, narratives are emergent, a joint venture and the outcome of negotiation by interlocutors. Allowing for interactional contingency is the hallmark of a sufficiently process-oriented and elastic model of narrative that opens up rather than closes off the investigation of talks business (Edwards, 1997: 142) and that accounts for the consequentiality and local relevance of stories. This alerts analysts to the dangers of attributing one sole purpose to the telling of a story that is, doing self. Tellers perform numerous social actions while telling a story and do rhetorical work through stories: they put forth

Downloaded from http://qrj.sagepub.com by RAJESH SINHA on April 27, 2009

382

Qualitative Research 8(3)

arguments, challenge their interlocutors views and generally attune their stories to various local, interpersonal purposes, sequentially orienting them to prior and upcoming talk. It is important to place any representations of self and any questions of storys content in the context of this type of relational and essentially discursive activity as opposed to reading them only referentially. The CA view of narrative as talk-in-interaction presents important implications not just for the analysis of narrative, but also for the processes and methods of data collection and transcription. The narrative data that form the mainstay of CA research arise naturally in conversations (be they in everyday, informal or institutional contexts). There is thus a clear privileging of conversational sites as the main event under scrutiny, and in that respect narrative becomes another format of telling (Edwards, 1997). By extension, narrative interviews are ultimately interactional data in which the researcher is very much part of the narrative telling, and his/her role should be not just reflected upon but also all contributions by the researcher, whether verbal or non-verbal, should be fully transcribed. As Potter and Hepburn (2005: 295) argue in relation to interview extracts in general, they should be transcribed to a level that allows interactional features to be appreciated even if interactional features are not the topic of study. Identifying and subsequently analysing closeup interactional features and language details in narrative tellings is central to the social-interactional project and, as discussed below, it constitutes the sine qua non toolkit for our style of narrative research.

Narrative as social practice

The view of narrative as talk-in-interaction is a necessary but not sufficient aspect of our SIA to narrative. It affords an intimate view of what is going on in the here-and-now of any narrative interaction firmly locating us in the flow of everyday lived experience. Nonetheless, the limitations of CA for the exploration of how any strip of activity is configured on the momentary-quotidianbiographical-historical frames and across socio-spatial arenas are by now well rehearsed (see Wetherell, 1998). Within the SIA to narrative, we can go beyond the local level of interaction and find articulations between the microand the macro-levels of social action and relationships (De Fina, 2003a: 2630; 2006). This navigation between a nose-to-data and a socio-culturally grounded project rests on the notions of social practice, genre and communities of practice as central to a new understanding of narrative. The SIA attempts to synthesize the local occasioning of narratives in conversations with their role in a variety of macro-processes, such as the sanction of modes of knowledge accumulation and transmission, the exclusion and inclusion of social groups, the enactment of institutional routines, the perpetration of social roles, etc. In this process of synthesis, narratives take different shapes and generic forms that are intimately related to those macro-processes and practices that constitute them. Thus, a major task of narrative analysis for

Downloaded from http://qrj.sagepub.com by RAJESH SINHA on April 27, 2009

De Fina and Georgakopoulou: Analysing narratives as practices

383

us is to unravel and account for the ways in which storytelling reflects and shapes these different levels of context, as opposed to e.g. focusing on story content and the goings-on within a story referentially and taking them as a relatively unmediated and transparent record (see Atkinson and Delamont, 2006: 17381). The process of contextualization of a narrative within the SIA involves linking it with the social practices it is part of. Practice captures habituality and regularity in discourse in the sense of recurrent evolving responses to given situations, while allowing for emergence and situational contingency. Thus, it allows for an oscillation between relatively stable, prefabricated, typified aspects of communication and emergent, in-process aspects. In our view, an important tool for bringing together narratives and social practices, for linking ways of speaking with the production of social life in the semiotic world, is the systematic investigation of narrative genres. We use the notion of genre not as the formal features of types of text, but rather, in tune with recent linguistic anthropology (Hanks, 1996; Bauman, 2001), as a mode of action, a key part of our habitus (Bourdieu, 1977) that comprises the routine and repeated ways of acting and expressing particular orders of knowledge and experience. As orienting frameworks of conventionalized expectations, genres shift the analytical attention to routine and socioculturally shaped ways of telling (Hymes, 1996) in specific settings and for specific purposes. Instead of treating narrative as a supra-genre with fixed structural characteristics, emphasis is placed on narrative structures as dynamic and evolving responses to recurring rhetorical situations, as resources more or less strategically and agentively drawn upon, negotiated and reconstructed anew in local contexts. Emphasis is also on the strategies that speakers use to deal with the gap between what may be expected (e.g. generic representations) and what is actually being done in specific instances of communication. At the same time, the incompleteness or smallness of narrative instances, be it in the sense of possibilities for revision and reinterpretation (Hanks, 1996: 244) or simply in the sense of narrative accounts in which nothing much happens, is firmly integrated into the analysis, as opposed to being seen as an analytic nuisance. The move to such a practice-oriented view of narrative genres also requires that we firmly locate narratives in place and time and scrutinize the social and discourse activities they are habitually associated with. In particular, it focuses attention on the social values of space as inscribed upon the practices (Hanks, 1996: 246) that take place within narrative tellings. The idea of narrative as part of social practices inevitably leads to pluralized and fragmented notions and also to new directions in the study of the way narratives function within groups. This link between groups and narrative activity has often been seen in sociolinguistics in terms of culture and social variables such as nationality or gender (e.g. Polanyi, 1985; Johnstone, 1990). However, the emphasis on practice brings to the forefront that people participate in multiple, overlapping and intersecting communities, so problematizing mainstay notions such

Downloaded from http://qrj.sagepub.com by RAJESH SINHA on April 27, 2009

384

Qualitative Research 8(3)

as that of a homogeneous speech community (cf. Rampton, 1999). There has thus been a definite move from large and all-encompassing notions of society and culture to micro, shrunk down, more manageable in size, communities of people who, through regular interaction and participation in an activity system, share language and social practices/norms as well as understandings of them with a community of practice seen as an aggregate of people who come together around a mutual engagement in an endeavour (Eckert and McConnell-Ginet, 1999: 191). When viewed as part of communities of practice, narratives can be expected to act as other shared resources, be they discourses or activities. In particular, they often form an integral part of a communitys shared culture as well as being instrumental in negotiating and (re)generating it (Goodwin, 1990; Georgakopoulou, 2006c). Put differently, they can be inflected, nuanced, reworked and strategically adapted to perform acts of group identity, to reaffirm roles and group-related goals, expertise, shared interests, etc. At the same time, they are also potentially contestable resources, prone to recontextualization, transposition across contexts and recycling, thus leading to other kinds of discourses (Silverstein and Urban, 1996; Shuman, 2005). In this respect, it is important to recognize the place of narratives in a trajectory of interactions as temporalized activities (De Fina, 2003b; Baynham and De Fina, 2005), and also in networks of practices which they are part of, represent and reflect on.

A summary

Our approach as outlined above has the following implications for doing narrative analysis:

1) It implies a close attention to both micro- and macro-levels, but always taking the local level of interaction as the place of articulation of phenomena that may find their explanation beyond it. Detailed transcription of the data, emphasis on the communicative how, the sequential mechanisms, and the telling roles and rights in the course of a narrative, are some of the hallmarks of the micro-analytic toolkit we are proposing. 2) It requires a careful examination of the way narrative tellings function as social practices and also within other social practices. This necessitates looking into genres as interconnections between social expectations about narrative form and emergence of meanings in concrete events. 3) It points to the historicity of narratives and their interconnections with practices. In this sense, narratives need to be studied as texts that get transposed in time and space, that (re)produce and modify current discourses, thus establishing intertextual ties with other narratives and other genres. An important methodological implication is the need to tap into trajectories of storytelling events that may take the form of either longitudinal studies or revisiting the same data with the reflexive distance of time (Riessman Kohler, 2002: 193214). 4) It indicates the need to be open to variability in narrative and to abandon predefined ideas about what narrative is, paying attention to non-canonical narratives

Downloaded from http://qrj.sagepub.com by RAJESH SINHA on April 27, 2009

De Fina and Georgakopoulou: Analysing narratives as practices and narrative formats and genres that have been neglected in mainstream research and understanding how they function in specific social contexts. Small story research (Bamberg, 2004; Georgakopoulou, 2006a, 2006b, 2007) is an important step in this direction and one that is compatible with the social-interactional paradigm. By employing small stories as an umbrella term for underrepresented narrative activities, small stories research has begun to chart the interactional and textual features of such activities and to document their links with their sites of occurrence, mapping out contextual factors that engender or prohibit the telling of small stories. Finally, its aim, as that of the SIA, is to work through the implications for identity research of including non-canonical stories in the focal concerns of narrative analysis. 5) It places emphasis on reflexivity in processes of data collection and analysis.

385

This means that, for example, transcription and translation are not seen as transparent processes, but as choices with strong implications for data analysis. Equally, it sees dichotomies such as natural versus elicited data as fundamentally flawed because it is committed to exploring how any setting in which narratives occur brings about, and is shaped by, different norms and histories of associations, participant frameworks and relations, etc. From a methodological point of view, the SIA does not set out to sanction or prescribe certain ways of working at the expense of others. However, its epistemological framework lends itself better to ethnographic kinds of methods that allow for local, reflexive and situated understandings of narratives as more or less partial and valid accounts within systems of production and articulation.

NOTES

1. Space limitations do not allow us to discuss and do justice to the counter-discourses to this canon, voiced by various prominent scholars within narrative inquiry (e.g. Catherine Riessman, Liz Stanley, Chris Weedon, to mention only three), who have put issues of researcher position and co-construction in the narrative process very firmly on the map.

REFERENCES

Atkinson, P. and Delamont, S. (2006) Rescuing Narrative from Qualitative Research, Narrative Inquiry 16: 17381. Bamberg, M. (ed.) (1997) Oral Versions of Personal Experience: Three Decades of Narrative Analysis, Journal of Narrative and Life History 7(14): 17784. Bamberg, M. (2004) Talk, Small Stories, and Adolescent Identities, Human Development 47: 33153. Bauman, R. (2001) The Ethnography of Genre in a Mexican Market: Form, Function, Variation, in P. Eckert and J. Rickford (eds) Style and Sociolinguistic Variation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Baynham, M. and De Fina, A. (eds) (2005) Dislocations/Relocations. Narratives of Displacement. Manchester: St. Jerome Publishing. Bourdieu, P. (1977) Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Cedeborg, A.C. and Aronsson, K. (1994) Co-narration and Voice in Family Therapy: Voicing, Devoicing and Orchestration, Text 14: 34570.

Downloaded from http://qrj.sagepub.com by RAJESH SINHA on April 27, 2009

386

Qualitative Research 8(3) De Fina, A. (2003a) Identity in Narrative: A Study of Immigrant Discourse. Studies in Narrative, no. 3. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. De Fina, A. (2003b) Crossing Borders: Time, Space and Disorientation in Narrative, Narrative Inquiry 13: 125. De Fina, A. (2006) Group Identity, Narratives and Self Representations, in A. De Fina, D. Schiffrin and M. Bamberg (eds) Discourse and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Eckert, P. and McConnell-Ginet, S. (1999) New Generalizations and Explanations in Language and Gender Research, Language in Society 28: 185201. Edwards, D. (1997) Structure and Function in the Analysis of Everyday, Journal of Narrative and Life History 7: 13946. Georgakopoulou, A. (2006a) Small and Large Identities in Narrative (Inter)-action, in A. De Fina, D. Schiffrin and M. Bamberg (eds) Discourse and Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Georgakopoulou, A. (2006b) Thinking Big with Small Stories in Narrative and Identity Analysis, Narrative Inquiry 16: 12937. Georgakopoulou, A. (2006c) The Other Side of the Story: Towards a Narrative Analysis of Narratives-in-Interaction, Discourse Studies 8: 26587. Georgakopoulou, A. (2007) Small Stories, Interaction and Identities. Studies in Narrative, no. 8. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Goodwin, C. (1984) Notes on Story Structure and the Organization of Participation, in J.M. Atkinson and J. Heritage (eds) Structures of Social Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Goodwin, C. (1986) Audience Diversity, Participation and Interpretation, Text 6: 283316. Goodwin, M.H. (1990) He-said-she-said: Talk as Social Organization among Black Children. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. Hanks, W.F. (1996) Language and Communicative Practices. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. Hymes, D. (1996) Ethnography, Linguistics, Narrative Inequality. Toward an Understanding of Voice. London: Taylor and Francis. Jefferson, G. (1978) Sequential Aspects of Storytelling in Conversation, in J. Schenkein (ed.) Studies in the Organisation of Conversational Interaction. New York: Academic Press. Johnstone, B. (1990) Stories, Community, and Place. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press. Labov, W. and Waletzky, J. (1967) Narrative Analysis: Oral Versions of Personal Experience, in J. Helm (ed.) Essays on the Verbal and Visual Arts. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. Ochs, E. and Capps, L. (2001) Living Narrative. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Polanyi, L. (1985) Telling the American Story: A Structural and Cultural Analysis of Conversational Storytelling. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Potter, J. and Hepburn, A. (2005) Qualitative Interviews in Psychology, Qualitative Research in Psychology 2: 281307. Rampton, B. (1999) Styling the Other: Introduction, in B. Rampton (ed.) Thematic Issue of Journal of Sociolinguistics 3: 4217. Riessman Kohler, C. (2002) Doing Justice: Positioning the Interpreter in Narrative Work, in W. Patterson (ed.) Strategic Narrative. New York: Lexington Books. Sacks, H. (1974) An Analysis of the Course of a Jokes Telling in Conversation, in R. Bauman and J.F. Sherzer (eds) Explorations in the Ethnography of Speaking. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Downloaded from http://qrj.sagepub.com by RAJESH SINHA on April 27, 2009

De Fina and Georgakopoulou: Analysing narratives as practices Shuman, A. (2005) Other Peoples Stories. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. Silverstein, M. and Urban, G. (1996) The Natural History of Discourse, in M. Silverstein and G. Urban (eds) Natural Histories of Discourse. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Wetherell, M. (1998) Positioning and Interpretative Repertoires: Conversation Analysis and Post-structuralism in Dialogue, Discourse & Society 9: 387412. ANNA DE FINAS research interests focus on narrative, identity, the discourse of immigrants and language contact phenomena. Her publications include Identity in Narrative (2003), Dislocations, Relocations, Narratives of Displacement, co-edited with Mike Baynham (2005), Discourse and Identity (2006) and Selves and Identities in Narrative and Discourse (2007) both co-edited with Deborah Schiffrin and Michael Bamberg. Address: Italian Department, ICC 307J, Georgetown University, 37th and O Streets NW, Washington DC 20015, USA. [email: definaa@georgetown.edu] ALEXANDRA GEORGAKOPOULOUS publications include Narrative Performances (1997), Discourse Analysis (co-authored with D. Goutsos, 2004) and Discourse Constructions of Youth Identities (co-edited with J. Androutsopoulos, 2003). She has recently explored the significance of everyday conversational stories for the sort of narrative and identity analysis that interview researchers do. This line of inquiry forms the subject of her latest book, Small Stories, Interaction and Identities (2007). Address: Department of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies/Centre for Language, Discourse and Communication, School of Humanities, Kings College London, Strand, London, WC2R 2LS, UK. [email: alexandra.georgakopoulou@kcl.ac.uk]

387

Downloaded from http://qrj.sagepub.com by RAJESH SINHA on April 27, 2009

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5834)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (824)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Psychometric Aspects of The W-DeQ WijmaDocument14 pagesPsychometric Aspects of The W-DeQ WijmaAnonymous Rq75cuX7100% (2)

- Cath FlyerDocument2 pagesCath FlyerChariss MangononNo ratings yet

- Empower B2 Reading PlusDocument20 pagesEmpower B2 Reading PlusFlorencia SanseauNo ratings yet

- Pud Unit 1 - 4 A 6to GradoDocument6 pagesPud Unit 1 - 4 A 6to GradoERIKA VARGASNo ratings yet

- Teacher Questioning Definition: Initiatives On The Part of The Teacher Which Are Designed To Elicit (Oral) Responses by The PurposesDocument5 pagesTeacher Questioning Definition: Initiatives On The Part of The Teacher Which Are Designed To Elicit (Oral) Responses by The PurposestrandinhgiabaoNo ratings yet

- PURPOSIVE COMMU-WPS OfficeDocument5 pagesPURPOSIVE COMMU-WPS OfficeKristine Joyce NodaloNo ratings yet

- University of Batangas Hilltop, Batangas CityDocument2 pagesUniversity of Batangas Hilltop, Batangas Cityhabeb TubeNo ratings yet

- Public Health CatalogDocument36 pagesPublic Health CatalogrrockelNo ratings yet

- CV 2018Document1 pageCV 2018Khangal SharkhuuNo ratings yet

- Confras Mod1 N PDFDocument7 pagesConfras Mod1 N PDFdexter gentrolesNo ratings yet

- Maths Time UnitDocument5 pagesMaths Time Unitapi-465726569No ratings yet

- Share 100 Writing Lessons PDFDocument240 pagesShare 100 Writing Lessons PDFsaradhahariniNo ratings yet

- 33 34 35 Test BankDocument24 pages33 34 35 Test Bankanimepenguin_610No ratings yet

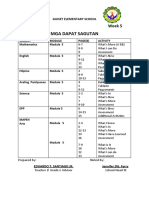

- Mga Dapat Sagutan: Grade 6 - EARTH Week 5Document3 pagesMga Dapat Sagutan: Grade 6 - EARTH Week 5Jhun SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Clil WaterDocument2 pagesLesson Plan Clil Waterapi-557070091No ratings yet

- Week 3 Diss-Home-Learning PlanDocument6 pagesWeek 3 Diss-Home-Learning PlanMaricar Tan Artuz50% (2)

- Nisichawayasihk Cree Nation Family & Community Wellness CentreDocument6 pagesNisichawayasihk Cree Nation Family & Community Wellness CentreNCNwellnessNo ratings yet

- Issc Meet 2024Document2 pagesIssc Meet 2024Ace E. BadolesNo ratings yet

- MLT IMLT Content Guideline 6-14Document4 pagesMLT IMLT Content Guideline 6-14Arif ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Application Form For Opening Senior High SchoolDocument8 pagesApplication Form For Opening Senior High Schoolfrancisco s.destura jr100% (2)

- The Conclusion: Your Paper's Final Impression: Strategies For Crafting A Pertinent, Thoughtful ConclusionDocument2 pagesThe Conclusion: Your Paper's Final Impression: Strategies For Crafting A Pertinent, Thoughtful ConclusionMike PikeNo ratings yet

- Carlos Enrique Cruz-Diaz v. U.S. Immigration & Naturalization Service, 86 F.3d 330, 4th Cir. (1996)Document4 pagesCarlos Enrique Cruz-Diaz v. U.S. Immigration & Naturalization Service, 86 F.3d 330, 4th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Pedagogical Province HESSEDocument7 pagesPedagogical Province HESSEFrancis Gladstone-QuintupletNo ratings yet

- Boy Scouts Training CourseDocument81 pagesBoy Scouts Training CourseKemberly Semaña PentonNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1: Introduction To Sales Enablement: Study GuideDocument6 pagesLesson 1: Introduction To Sales Enablement: Study GuidefretgruNo ratings yet

- Math9 Q1 M9 FinalDocument15 pagesMath9 Q1 M9 FinalRachelleNo ratings yet

- SPELD SA Set 6 Sant The Ant Has lunch-DSDocument16 pagesSPELD SA Set 6 Sant The Ant Has lunch-DSLinhNo ratings yet

- Existing Tools For Measuring or Evaluating Internationalisation in HEDocument2 pagesExisting Tools For Measuring or Evaluating Internationalisation in HEJanice AmlonNo ratings yet

- Commonly Asked Interview QuestionsDocument6 pagesCommonly Asked Interview QuestionsejascbitNo ratings yet

- Ba Eng Sem 2Document3 pagesBa Eng Sem 2Divya MalikNo ratings yet