Professional Documents

Culture Documents

DocumentsR Permani

DocumentsR Permani

Uploaded by

Uwes FatoniOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

DocumentsR Permani

DocumentsR Permani

Uploaded by

Uwes FatoniCopyright:

Available Formats

The Journal of Socio-Economics 40 (2011) 247258

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

The Journal of Socio-Economics

j our nal homepage: www. el sevi er . com/ l ocat e/ soceco

The presence of religious organisations, religious attendance and earnings:

Evidence from Indonesia

Risti Permani

School of Economics, University of Adelaide, Napier Building, North Tce, Adelaide, South Australia 5070, Australia

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history:

Received 27 January 2010

Received in revised form

21 December 2010

Accepted 30 January 2011

JEL classication:

J17

J22

L31

R20

Z12

Keywords:

Religiosity

Earnings

Religious institutions

Time allocation

Religious and physical distance

Indonesia

a b s t r a c t

This article examines the socio-economic signicance of religious institutions in non-western commu-

nities using data from a survey of around 500 heads of households across nine Pesantren in Indonesia.

It nds that local community benets from more intense interaction with the local religious leaders of

Islamic boarding schools (Pesantren) than does the external community. But the direct benet of living

close to Pesantren only matters for religious participation, not for earnings. However, the study nds

that religiosity is more positively signicant for earnings of the community surrounding the Pesantren,

probably due to networking effects. Hence, community involvement of religious leaders can indirectly

and positively affect earnings of the surrounding community. The overall results suggest that Pesantren

contribute to the formation of social capital, particularly in the form of religiosity, which contribute to

the improved welfare of the surrounding community.

2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Research has shown that there are substantial variations by

religion and religiosity in earnings. At the macro level, a cross-

country studies nds a positive association between economic

growth and religious beliefs but a negative association between

economic growth and church attendance (Barro and McCleary,

2003). At the individual level, while there have been some stud-

ies suggesting the association between religious attendance and

earnings (Tomes, 1984, 1985; Lipford and Tollison, 2003; Lehrer,

2004; Lile and Trawick, 2004; Chiswick and Huang, 2008), only a

few offer thorough empirical works to explain how exactly reli-

gious institutions affect the association: does it the leader, physical

distance, or religious distance matter? Even fewer studies use data

from non-western countries.

To ll a void in the literature, the objective of this study is to

analyse the relationship between religious attendance and earn-

ings among Indonesian Muslimhead of households and to see how

aspects of religious institutions contribute to the formationof these

E-mail address: risti.permani@adelaide.edu.au

relationships. To what extent are differences in earnings and edu-

cational choices due to schooling, marital status, age, etc. are issues

that have been examined by many studies. Unique features of this

study are to what extent individual earnings are inuenced by their

distance to a worship place (both geographical and religious dis-

tances), degree of religiosity (frequency of religious attendance)

and the role of religious leaders.

The context of this study which focuses on non-western com-

munities gives a comparative analysis relative to the existing

studies on the economics of religiosity. Most of themobserve com-

munities inwesterncountries especially the US. Astudy onIslamin

Indonesia argues that in Indonesia there is no separation between

state and church (Tamney, 1979). The Indonesian government is

actively involvedinreligionandencourages participationfromvar-

ious religious organisations to develop social capital.

1

This reects

howreligious values are seen as more important and integrated on

a larger scale to many aspects of ones life in Indonesia than in the

1

It is important to note that according to Tamney (1979) the Indonesian govern-

ment afrms religion is not a religion (p. 127). Religious freedom is well protected

by the national constitution.

1053-5357/$ see front matter 2011 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.socec.2011.01.006

248 R. Permani / The Journal of Socio-Economics 40 (2011) 247258

US. In addition, with ve times compulsory daily prayers the prac-

tise of Islammight be relatively more time time-intensive than the

practise of other religions leading to higher opportunity costs of

religious activities. Therefore, from an econometrics point of view,

the inclusionof religious attendance inthe earnings equationmight

be important to avoid omitted variable bias in earnings estimates.

Also, from a policy analysis point of view, analyses of the deter-

minants and effects of religious attendance might have important

policy implications.

To look at the effects of Indonesian Muslim heads of house-

holds religious attendance on earnings, I use data from a recent

survey of communities surrounding Pesantren (Islamic boarding

schools) across three provinces in Indonesia. In the education sec-

tor, Pesantrens role has been well known, especially for providing

educationfor low-incomefamilies. For thepast four years, thenum-

ber of Pesantren has increased from 14,067 in the academic year

2002/2003 to 17,506 in the academic year 2006/2007. The schools

provided education to over 3 million students during the period.

While the formal structure of the organisation of Pesantren is as an

educational institution, Pesantren in Indonesia also act as centres

of Islamic teachings aiming to develop the human capital of their

students as well as the surrounding community. The schools there-

fore are ideal case studies to observe the links between religious

attendance, education and community welfare.

A new approach is used to allow the use of cross-sectional data

to analyse the role of Pesantren informing the relationshipbetween

religious attendance and earnings. In an ideal research design,

comparison between religiosity and other community character-

istics of the same individuals before and after the establishment

of Pesantren could predict the impacts of Pesantren better.

2

But

given most Pesantren were established decades ago, such data are

unfortunately not available. I therefore include a residence location

variable differing between the within and outside communities

based on their distance to the nearest Pesantren.

3

I apply standard

ordinary least-squares (OLS) methods for earnings and conduct

some robustness checks regarding limitations of religiosity mea-

sures and possibilities of non-random residence selection. I use

ordered probit to analyse determinants of religiosity.

The within-versus-outside approach, however, brings some

unique features to this study.

4

It allows one to look at two types

of distances: physical and religious distances. Where time and

resource allocation becomes the key point in the Azzi and Enhren-

bergs model on household allocation to religious activities, any

factor which can shift time and budget allocation should be closely

examined including the physical distance to a worship place and

other benets which might arise from living close to it.

5

I also

2

Usingthedifference-in-differenceestimator andassumingthecommunitychar-

acteristics between the within and outside area would have been the same had no

Pesantren been established.

3

The former refers to the internal community located within walking distance

to Pesantren, while the latter is located between 5 and 10km from Pesantren as the

control cohort.

4

Furthermore, the selection of Muslim (believers in Islam) in Indonesia provides

two advantages in terms of contribution to the literature. First, the respondents

represent individuals whose religious afliations require frequent attendance since

their religion, Islam, commands themtopractice ve-time dailycompulsoryprayers.

Second, transportation costs to worship places might play important roles in their

decision to attend the mosque, given lowaverage income compared to respondents

in western countries. Although I develop the theory based on theoretical models

previously applied to western countries, the empirical results fromthis study would

then showwhether the theoretical framework are supported by data fromdifferent

communities.

5

In addition, Glaeser et al. (2002) predict that an individuals decision to accu-

mulate social capital might be related to physical distance. Hence the study can

suggest how social capital in terms of community support from the Pesantren

differs between communities whose geographical distances to a worship place are

different. The within-versus-outside framework can also test literature on repeated

take into account various characteristics of Pesantren as a proxy

for religious distances. Studies assume religious bodies or religion

as a collective action of their members (Wallis, 1990; Iannaccone,

1992).

6

The equilibrium, i.e. church actual attendance is therefore

shaped when individual preference conforms to church charac-

teristics. The argument suggests that the characteristics of the

religious institutions where an individual regularly attends the ser-

vices reect an institution with the closest religious distance for a

givenphysical distance (andholding other factors constant). There-

fore, the inclusion of variables on distance to a worship place (both

religious and physical distances) gives indication of how individu-

als deal with the trade-off between costs of religious attendance

and religious conformity. Further discussion is included to see

related concepts on this matter, namely whether localism or reli-

gious conformity is more signicant in the relationship between

religious bodies and communities in Indonesia.

The paper develops a simple theoretical foundation in Section 2

and provides empirical analysis in Sections 4 and 5. The theoreti-

cal prediction suggests that: (i) religious attendance might matter

for earnings; (ii) the individuals decision on religious attendance

might be affectedby strictness of local religious institution(i.e. reli-

gious distance) and his residence location relative to the worship

place (i.e. physical distance). I nd statistical evidence to support

the rst hypothesis and some explanations to explain the second

hypothesis. First, I nd that religiosity more matters for earnings in

the neighborhood surrounding the religious institutions probably

duetonetworkingeffects. Second, individuals decisiononreligious

attendance is signicantly affected by whether or not the religious

leader or Kyai is involved in the community. The role is to a lesser

extent in the community where more religious institutions present

inthecommunitysuchas intheexternal communityindicatingthat

competition in the religious market is similar to competition in

any goods market.

The remainder of this paper consists of ve sections. Section 2

derives a simple theoretical framework to conclude two hypothe-

ses that will be tested by the empirical analysis. Section 3 provides

a background of Pesantren and their current performance as well

as the dataset. Section 4 presents the results from wage regres-

sions as well as some robustness checks. Section 5 explores the

determinants of religious attendance. Section 6 concludes.

2. A simple theoretical framework

There are two hypotheses being tested using empirical works:

(i) religious attendance is signicant for earnings; (ii) characteris-

tics of religious institutions and distances between individuals and

religious bodies matter for religious attendance. Theoretical foun-

dations in this section determine the necessary control variables

and provide predictions for their effects on the outcomes.

I beginwitha standardreduced-formearnings regressionmodel

taking into account a religiosity factor:

log(w

i

) =

1

X

i

+

2

R

i

+e

i

(1)

where w

i

is an hourly wage rate, X

i

an individual characteristic, R

i

degree of religiosity (proxied by number of religious visits) and e

i

games (Fudenberg and Maskin, 1986; Abreu, 1988): whether cooperation becomes

easier when individuals expect to interact more often. It is expected that the within

community interacts more with religious clerics. This might lead to a higher accu-

mulation of return to social networking.

6

Wallis (1990) formulates church characteristics by average participation rates

determined by members contribution, while Iannaccone (1992) denes the quality

of a church as the average religious quality (or perhaps more suitable to refer to as

religiosity) of its members.

R. Permani / The Journal of Socio-Economics 40 (2011) 247258 249

the error term. The use of an hourly wage rate controls a possibility

of increases in earnings due to increases in hours of working.

7

In this study, I include religious institutions characteristics

(

P

k

) to avoid omitted variable bias. The variable is assumed to be

exogenous. The role of religious institutions in earnings can be

explained by one (or combination) of two possible explanations.

First, religious institutions might provide human capital develop-

ment programs such that the program increases the wage rate, i.e.

direct effects. Second, religious institutions might attract more fre-

quent religious attendance of individuals. Then, increased religious

attendance might provide some mechanisms to benet the individ-

uals from attending the mosque, for example through networking

effects. The second implies indirect effects of religious institutions.

There is a possibility that those effects differ between individu-

als living close to the religious institution and individuals in the

external community.

Given the above illustration, the reduced-form model of indi-

vidual i where religious institution k is the nearest large religious

worship place in the area:

log(w

ik

) =

1

X

ik

+

2

R

ik

+

3

P

k

+

4

(R

ik

d

ik

) +v

ik

(2)

where d

ik

refers to a dummy variable of residence location. It equals

tooneif theindividual lives inthesurroundingcommunityandzero

if he lives in the external community.

In order to understand the formation of religious capital, the

next relevant question is why might distance matter as denoted

by d

ik

for religious attendance? In the following I derive a static

analysis of religious participation similar to Becker (1965).

8

Two

key aspects being focused are individual time allocation and the

prices that the individual pays for religious commodities (Becker,

1965). Religious commodities are taken into account in the individ-

ual utility functionfollowing a seminal work by Azzi and Ehrenberg

(1975).

9

Following Sullivan (1985), I focus on the individual, more

specicallytheheadof household, rather thanthewholehousehold

and religious activities generate immediate utility rather than just

the expectations of a stream of afterlife consumption benets.

10

However, unlike Sullivan (1985), I follow Sawkins et al. (1997) by

ignoring tax effects.

11

Thus, the income is simply dened as after-

tax income.

7

For example, as a result of increases in religious attendance which in turn

decreases the marginal rate of substitution between consumption and leisure (e.g.

increased work ethics).

8

One may argue that suchsetting is not suitable for ananalysis of religious partic-

ipation. Azzi and Ehrenberg (1975) argue that a static household-allocation-of-time

model assuming that the expected stream of benets which an individual plans

to receive terminates at the time of his death is inappropriate for a model of reli-

gious participation because most religions promise their followers some afterlife

benets. However, in their model, expected afterlife consumption is simply a func-

tion of time spent in religious-activities. The time spent in religious activities is

then dened as a function of wagefrom which the analysis can predict that age-

religious participation prole may be U-shaped. The overall results would not be

changed if religious commodities (as a function of time spent in religious activities)

directly enter the utility function as long as an assumption that religious commodi-

ties areproducedbasedonindividuals belief inafterlifebenets holds. Furthermore,

assuming age-effect is controlled the number of religious commodities the indi-

vidual consumes can be determined within a static analysis framework based on

a similar mechanism as of secular consumption. Otherwise, we must impose a

strong assumption that an individual for example migrates in every period. Such

condition is not what I aim to observe.

9

The theoretical model is more recently used as a theoretical baseline in some

empirical studies for example Sullivan (1985) and Sawkins et al. (1997).

10

There is a possibility of immediate benet of religious activity. Individuals

with materialistic views would increase public religious attendance because it can

increase career opportunity through networking. Religiosity can also increase earn-

ings if it improves work ethic and conducts.

11

While taxation might be an important aspect in the future work, information

on tax in Indonesia is very limited and hence it is not uncommon to observe that

individuals do not take into account the tax rates in their decision making. This is

especially true for those who work in the informal sector. This is the sector in which

most Indonesians are working.

I assume that individuals combine time and goods purchased

on the market to produce consumption (C) and religious commodi-

ties (R) that directly enter their quasi-concave utility functions

U=U(C,R).

12

Individuals produce i-number of goods Candj-number

of religious commodities Rbasedontwoproductionfunctions. They

are concave and twice differentiable:

C

i

= g

i

(x

Ci

, T

Ci

) and R

j

= f

j

(x

Rj

, T

Rj

, T

Vj

) (3)

where x

Ci

and x

Rj

are vectors of market goods for producing con-

sumption and religious commodities, respectively; T

Ci

and T

RJ

vectors of time inputs used in consuming consumption and reli-

gious commodities, respectively. Time needed to produce religious

commodity (T

Rj

) only consists of the worship time. The partial

derivatives of C

i

with respect to x

Ci

and T

Ci

as well as the partial

derivatives of R

j

with respect to x

Rj

and x

Tj

are non-negative, while

the second derivatives are negative. T

Vj

is travel time. The partial

derivative of R

j

with respect to T

Vj

is negative.

Individuals combine goods and time via production functions g

i

andf

i

basedonutilitymaximization. The goods constraint is needed

to impose the bound on resources and can be written as:

n

i=1

p

Ci

x

Ci

+

m

j=1

p

Rj

x

Rj

= V +T

W

W (4)

where P

Ci

and p

Rj

are vectors giving the unit prices of x

Ci

and x

Ri

,

respectively, T

w

a vector giving the hours spent at work, w a vector

givingthe earnings per unit of T

w

andVis other income. Throughout

this section, I assume the wage is constant.

The time constraints can be written as: T =

n

i=1

T

Ci

+

m

j=1

(T

Rj

+T

Vj

) +T

w

The production functions can be written in the equivalent form

as theinput per unit of commodity: x

Ci

=m

Ci

C

i

; x

Rj

=m

Rj

Rj; T

Ci

=t

Ci

C

i

;

T

Rj

=t

Rj

R

j

; T

Vj

=t

Vj

R

j

where m

Ci

and m

Rj

are vectors giving the input

of goods per unit of C

i

andR

j

, respectively; T

Ci

, T

Rj

andT

Vj

are vectors

giving the input of time per unit of C

i

and R

j

, respectively.

Substituting T

w

using the time constraint and then substituting

x

Ci

, x

Rj

, T

Ci

, T

Rj

, T

Vj

the budget constraint can be written as:

n

i=1

(p

Ci

m

Ci

+t

Ci

w)C

i

+

m

j=1

(p

Rj

m

Rj

+(t

Rj

t

Vj

) w)R

j

= V +T w (5)

The above equation suggests that the full price of a unit of a reli-

gious commodity R

j

is the sumof the prices of the goods and of the

time (worship and travel time) used per unit of R

j

. Similar inter-

pretation is for a consumption commodity C

i

. Travel time increases

the full price of religious commodity with particular reference to

indirect prices in the form of forgoing of income.

Assuming other factors constant, the equilibrium condition

resulting from maximising utility subject to the above constraint

takes a very simple form:

MRS

RC

=

p

Rj

m

Rj

+(t

Rj

+t

Vj

) w

p

Ci

m

Ci

+t

Ci

w

(6)

12

One example of consumption commodities is sleeping as suggested by Becker

(1965). Sleeping depends on the input of a bed and time. Note that sleeping has a

more direct effect on individuals utility than a bed. An example of religious com-

modities is attending the worship place (or mosque for Muslims) which depends on

theinput of religious clothes, ownershipof theholybook(or theQuranfor Muslims),

and time. Ownership of the holy book might not give direct utility to the individ-

ual. But if he goes to a worship place and study the meaning of the holy book, the

knowledge he accumulates from attending the worship place will give more direct

utility. In addition, I assume that religious commodities have strong and positive

correlation with belief in afterlife consumption. This assumption can be relaxed by

using an approach introduced by Montgomery (1996a,b).

250 R. Permani / The Journal of Socio-Economics 40 (2011) 247258

Taking into account travel time, a higher marginal rate of substi-

tution between consumption and religious commodities suggests

that the individual must give up more units of consumption com-

modities (C) to obtain one additional unit of religious commodities

(R) relative to the MRS based on a model which does not take into

account travel time.

The model simply predicts that living distant from a worship

place may discourage one to attend religious services given its high

opportunity cost. If we use the same principle in dening the link

betweenreligious distanceandreligious attendance, wewill expect

to see reasons to why people do not attend local religious services.

But the explanation is not due to higher opportunity cost (or MRS)

but it is most likely due to lower marginal utility of worship time.

This is explained in the following.

In addition to distance, religious attendance might also be

affected by the characteristics of the religious institution to pre-

dict religious distances. Here I followthe basic idea of Montgomery

(1996a,b) that religious commodities are a function of religious

institutions strictness.

13

But I dene that the religious institutions

strictness can be proxied by the time the institution requires its

members to involve inreligious activities (

T

R

). I assume

T

R

is exoge-

nous. I assume that two variables

T

R

and T

Rj

affect the production

functionof religious commodities throughavariablereligious con-

formity (S

j

).

R

J

= f

j

(X

Rj

, S

j

(|T

Rj

T

R

|)) (7)

S

j

is increasing inR

j

. The individual aims to matchhis time allocated

to religious activities (T

Rj

) with the time required by the religious

institution (

T

R

), i.e. to minimize |T

Rj

T

R

|. I assume the functional

form is as the following:

S

j

=

1

|T

Rj

T

R

|

(8)

Although the inclusion of institutional strictness does not

change either resources or income constraints, it changes marginal

utility of time spent in religious activities depending on the rel-

ative magnitude between

T

R

and T

Rj

. Since |T

Rj

T

R

|

3

is always

positive, to increase his utility, an individual whose time spent

in religious activities is below the amount of time required by the

religious institution will increase his time allocated to religious

activities, vice versa.

14

The model suggests that the individuals

decision on how much time spent in religious activities might

actually reect religious distances between the individual and a

local religious institution not simply taking into account trade-offs

between leisure, work and pray. The religious distance might then

(indirectly) affect the wage rate.

To reiterate, the theoretical foundations dened in this sec-

tion suggest the following hypotheses to be tested using empirical

works controlling for necessary variables:

H1. Religious attendance matters for earnings.

H2. The distance to a worship place discourages one fromattend-

ingreligious services, whilereligious conformityincreases religious

attendance.

13

Montgomery (1996a,b) notes that the equilibrium condition suggests that an

individual would choose a level of strictness inversely proportional to his wage

level.

14

Mathematically,

U

T

Rj

=

(T

Rj

TR)

T

Rj

TR

3

_

U

R

j

R

j

S

j

_

. .

(+)

3. Background

3.1. The school (Pesantren)

The religious institution being focused on in this study is

Pesantren. Pesantren or Islamic boarding schools are indigenous

Islamic educational institutions in Indonesia. Based on their

objectives, Pesantren can be classied into three types: Salayah

(traditional), Khalayah (modern) and Combination. The study of

classical Islamic text has often been associated with the Salayah

Pesantren. Most Nahdlatul Ulama (NU)-afliated Pesantren are

classied as this type. In contrast, formal education has been inter-

preted as an essential part of Khalayah Pesantren. Some Pesantren

canbedenedbytheologicallySalayahbut structurallyKhalayah.

Thus, instead of reciting classical Islamic manuscripts (Kitab Kun-

ing; literally the yellow book) through their informal education,

these Pesantren also offer formal education, which contain more

Islamic courses.

In providing academic services, Khalayah Pesantren have to

choose either the Ministry of Religious Affairs (MRA) curriculum

or the Ministry of National Educations (MNE) curriculum. The MRA

curriculumcontains more Islamic coursework study hours thanthe

MNEcurriculum. However, therearesomePesantrenthat useMRAs

curriculum, but also have formal schools that use the MNE curricu-

lum. In the 2005/2006 academic year, Santris or Pesantren students

who attend MRA-curriculum schools are over 70% of total Santris

who attendformal schools, namely 72%, 78%, 73%and74%of Santris

attending primary, junior secondary, senior secondary schools and

university, respectively.

Formal schools with MRA curriculum are called Madrasahs,

or schools in Arabic. The Madrasahs vary from primary schools

(MadrasahIbtidaiyah), junior highschool (MadrasahTsanawiyah), to

senior high school (Madrasah Aliyah). The MNE curriculum schools

are named Sekolah (literally, school in bahasa), which vary from

primary school (Sekolah Dasar), junior high school (Sekolah Menen-

gah Pertama), to senior high school (Sekolah Menengah Umum). In

Indonesia, primaryschool, junior highschool andsenior highschool

are year 16, year 79, and year 1012, respectively.

With over 3 million primary school students and nearly 3 mil-

lion secondary school students, the importance of Pesantren in the

contemporary Indonesian educational sector is evident. For the

past four years the number of Pesantren has increased from 14,067

in the academic year 2002/2003 to 17,506 in the academic year

2006/2007. This number is equal to7%of total students inIndonesia

from primary to senior secondary schools. Adding to increased

enrollment, Pesantren education has no sign of gender disparity

with 50% of students are females.

15

The Pesantren educational system has undergone considerable

transformations and encouraged their students to attend formal

schools. In the academic year 2002/2003, only 38.5% of total Santris

attended formal schools. Four years later, the percentage increased

to 57.75%. This trend follows a decreasing share of traditional

Pesantren (Salayah) from 63.3% in the academic year 2002/2003

to only a half of it in more recent years.

16

15

Asadullah and Chaudhury (2008) reports similar percentage using data from

Madrasah in Bangladesh.

16

While there seems to be transition in the curriculum and activities within

Pesantren, Pesantren afliation to external organisations has been relatively

unchanged. Over the years, over 60% of Pesantren are afliated to Nahdlatul Ulama

indicating the importance that mass organisation plays in the spread of Islamic edu-

cation in Indonesia. Less than 2% of Pesantren are afliated to Kyai. Note that while

60% of Pesantren are NU-afliated, only 30% of total Pesantren are salayah. This

implies that either/both some NU-afliated Pesantren have transformed themselves

intocombinationPesantrenor/andnewlydevelopedNU-Pesantrenclaimthemselves

as combinationPesantren. These transitions are probably linkedto the governments

R. Permani / The Journal of Socio-Economics 40 (2011) 247258 251

In addition to their roles in the education sector, unlike schools

in other countries, many Pesantren also engage in the business

sector. Cooperatives, Islamic micronance units (Baitul Maal Wa

Tamsil or BMT), bookshops and supermarkets are some of popu-

lar business forms in Pesantren. Having these income-generating

units seems to signicantly help Pesantren to develop their self-

nanced management. This can be seen between the academic

year 2003/2004 and 2004/2005 total contribution of central and

local governments have decreased from over 20% to 16% of total

income. Donation including almsgiving (zakat) has also decreased

from 30.9% to only 10% of total income. In contrast, the internal

income sources including Pesantrens business units and tuition

fees paid by parents have increased from 43% in the academic year

2003/2004 to 62.1% in the academic year 2004/2005.

17

Given the

Pesantrens activities in the education and business sectors as well

as their position as religious centres, it is interesting to nd how

they interact with the surrounding community. No previous study

has quantitatively explored these issues using data from Pesantren

in Indonesia.

3.2. Data

Inthis study, I use data froma survey in2007collecting informa-

tionfromnearly500households.

18

Thestudylimits theobservation

to Muslim respondents. I also limit our observations to the head of

households. This approach assumes that heads of households are

the decision makers. Three potential income determinants include

frequency of religious attendance, the geographical location of the

household and selected Pesantren characteristics as well as the

interaction terms between these variables. The geographical loca-

tion of the household is represented by a binary variable, i.e. value

of one if the households live in the internal community.

Table 1 presents the summary of statistics of the heads of

households (HH) by proximity to a Pesantren. Two dependent

variables being observed and selected individual characteristics

normally associated with earnings show insignicant differ-

ence between respondents living close to and outside Pesantren

areas at 5% level of signicance suggesting similar socio-economic

characteristics between two types of communities. But note that

the within community has indeed lower religious participation.

The only signicant difference is in head of households preference

on Shariah-compliant nance. The variable might suggest differ-

ent degree of religiosity. It is therefore interesting to see whether

Pesantren contributes earnings by controlling for more control vari-

ables.

More detailed summary of statistics by the type of Pesantren

can be obtained from the author. Important information is that it

is statistically signicant that respondents living close to a tradi-

tional Pesantren have lower human capital as indicated by written

skills and lower schooling years than respondents living close to

other types of Pesantren. Also, the nature of traditional Pesantren

which value religious education more than regular subjects seems

regulation on reduction in religious courses. They can also be due to changes in

demands from the education and the labour market. Either way, it seems that

Pesantren in Indonesia have indeed been able to adapt to changes in the educational

sector.

17

Note that there is also a possibility that the low proportion of income from

the government is due to a small percentage of government-hired teachers, called

Pegawai negeri sipil (government ofcials). On average, only 5% of teachers are

salaried by the government. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that Pesantren

indeed manage their schools as private schools.

18

The survey was conducted by a team of researchers from the University of

Adelaide (Australia) and Bogor Agricultural University (Indonesia) funded by the

AustraliaIndonesiaGovernanceResearchPartnership(AIGRP) at AustralianNational

Universityin2007. Thesurveywas designedtoanalysetheimpact of religious organ-

isations and Madrasah on social capital and democratic performance in Indonesia.

to affect HHs preference on percentages (of total schooling hours)

of religious courses that they think is ideal for their children. Fur-

thermore, respondents living close to a modern Pesantren earn

more. This might be related to the statistics informing that those

who live close to traditional Pesantren receive lower education. In

contrast, respondents living close to a modern Pesantren demand

less in the proportion of religious education they want their chil-

dren to receive. The statistics indicate possibilities of signicant

effects of Pesantren characteristics on earnings.

19

4. Basic regressions

4.1. Individual earnings

First, I analyse whether the religiosity is a determinant of earn-

ings using the OLS method. In computing the standard errors, I

allow for arbitrary community-level spatial correlation. Hence,

the standard errors are clustered at the community level. I use the

following reduced-form model to dene the wage rate of individ-

ual i who lives close to Pesantren j and whose frequency of religious

attendance is in m-th category:

log(wage

ij

) =

0

+

3

m=1

1m

R

ijm

+

2

d

ij

+

3

m=1

3m

R

ijm

d

ij

+

P

p=1

4p

X

ijp

+

L

l=1

5

Q

jl

+

H

h=1

6

V

jh

+

ij

(9)

R

ijm

refers to a vector of religious attendance equals to one if the

respondent is in the m-category (m=0 (never); 1 (sometimes); 2

(very often or always)). I include P number of individual character-

istics (X

ij

), L number of Pesantren j characteristics (Q

j

) and dummy

variable on residence location (d

ij

). The individual characteristics

consist of marital status, age, number of kids aged between 0

and 14, years of schooling, and categorical variables of endowed

wealth proxied by the ownership status of their residence.

20

The

later might affect ones decision on labour participation. Pesantren

characteristics include Kyai (religious leader)s age and experience

(years of services), Pesantrens year of establishment, whether the

Kyai guides the community.

I also include community control variables (V

j

) to take into

account competition (could also be complementarity) effects

betweenPesantren andother religious institutions.

21

The basic idea

is toensureincreases inreligiosityareonlyaffectedbythePesantren

instead of other religious bodies in the area. In the present paper,

19

Appendix 5c presents the summary statistics of Pesantrens characteristics by

modern Pesantren.

20

The respondents were asked about the ownership of dwellings: What is the

ownership status of dwelling? Options: (1) owned with title; (2) owned without

title; (3) given by relation or other to use; (4) provided by the government.

21

It is difcult to analyse any system in Pesantren without exploring the role of

the Kyai. Indeed, this is the main aspect which distinguishes between Pesantren

and other schools (Binder, 1960; Geertz, 1960; Lukens-Bull, 2000; Abdurrahman,

2006). Literature reviewshows that the Kyais roles in Pesantren are not only signif-

icant from religious perspectives but also from economic, cultural, educational and

political perspectives. The Kyai are seen as cultural brokers for the ow of modern-

ization (Syahyuti, 1999; Anshor, 2006) wealthy landowners (Dhoer, 1999, p. 34),

teachers of a modern discourse but a distinctly Islamic way (Lukens-Bull, 2000),

decision makers who are not only distributing new skills and knowledge but also

deciding which ones are lawful (Halal) and which are not (Haram) for his Santri

(Abdurrahman, 2006) and in Java the Kyai even claim their Pesantren as small king-

doms, in which they have absolute authority (Dhoer, 1999, p. 34). In a broader

scope, the Kyai also play strategic and inuential role in politics. There have been

substantial numbers of literatures that reveal about this issue (Binder, 1960, p.

254255; Geertz, 1960; Horikoshi, 1975; Turmudi, 2006). Indeed, in recent years,

the existence of Pesantren is more acknowledged from its political importance than

its educational function. It is due to Pesantrens success in producing political elites.

252 R. Permani / The Journal of Socio-Economics 40 (2011) 247258

Table 1

Summary statistics by proximity to Pesantren.

Variables Outside Pesantren area Close to Pesantren Difference =(2) (5)

N Mean St.dev. N Mean St.dev.

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6)

1. Religious outcomes

HHs expected religious course 211 51.15 12.00 254 52.85 10.34 1.7

HHs participation at religious activities (1=never; 2=sometimes; 3=frequent) 188 2.48 0.69 234 2.43 0.71 0.06

2. Individual characteristics

HHs marital status 221 0.94 0.24 260 0.95 0.21 0.01

No. children aged 014 years 221 1.62 0.91 259 1.76 1.03 0.14

Ability to write (0=no; 1=yes) 220 0.95 0.21 260 0.92 0.27 0.03

HHs schooling years 217 9.62 4.46 258 9.33 4.92 0.29

Work in the agricultural sector (0=no; 1=yes) 221 0.24 0.43 260 0.22 0.41 0.02

HHs type of job (1=in religious sector, 0=otherwise) 221 0.08 0.27 260 0.09 0.29 0.01

3. Income and expenditure

HHs (natural log) monthly income (Rupiah) 221 14.27 0.91 260 14.26 0.89 0.01

HHs (natural log) expenses on clothes 218 12.78 0.88 250 12.68 1.07 0.1

4. Religion-related preference

HHs preference on type of nancial institution (0=conventional; 1=Shariah-compliant) 101 0.13 0.34 117 0.04 0.18 0.09

**

HHs donation to Muslim (1=never; 2=rarely; 3=sometimes; 4=frequent) 219 3.18 0.88 257 3.27 0.80 0.09

Notes: Samples are Muslim males and have roles as the head of households (HH).

**

Difference is signicant at 5%.

thetheoretical baselineanddatadescriptionimplicitlyassumes that

Pesantren is a single religious provider in the community.

22

Fortu-

nately, the survey collects data on community facilities available

bothinthe withinandoutside area including the presence religious

organisations such as NU, Muhammadiyah, HTI, LDII, PERSIS, etc.

23

These alternative religious bodies might also contribute to respon-

dents religiosity. There are two strategies I use here. First, I include

two dummy variables to control for the presence of two largest

religious organisations, namely NU and Muhammadiyah. Second, I

consider the competition effect. A previous empirical study shows

that competition between religious bodies can affect their mem-

bers voluntary contribution as a proxy of religiosity (Zaleski and

Zech, 1995). I therefore include the Herndahl index (H

ijk

) in the

regression: H

ijk

=

n

ij

k=1

share

ijk

; where i,j,k refer to individual i liv-

ing in surrounding of the Pesantren j having k alternative religious

bodies. share

ijk

is the market share of k-threligious body inthe area,

i.e. number of its members per total members of all religious bodies

in the area.

Table 2 reports OLS estimation of earnings functions. Column

(1) includes the Pesantren xed effects. The coefcient for fre-

quent mosque attendance is positive and signicant. Compared

to those who never attend religious activities, respondents who

frequently attend religious activities earn nearly 35% more. The

size and signicance of this coefcient is robust when I include

22

Now let us re-assess the regression method discussed previously. Now assume

that there are two treatments being observed. Both treatments might have an effect

on the outcome, i.e. religiosity. The rst treatment (T

1

) is the main focus of this

study, i.e. the effect of living close to a Pesantren. For simplicity, I assume the sec-

ond treatment (T

2

) is the effect from an alternative religious body in the outside

area. Consequently, respondents in the within area become the control group of

treatment 2 (C

2

) and respondents in the outside area become the control group of

treatment 1(C

1

). I observe: D = E[R

T1

i

T

1

, C

2

] E[R

T2

i

T

2

, C

1

]. Adding andsubtract-

ing E[R

C1

i

T

1

, C

2

], I obtain: D = E[R

T1

i

T

1

, C

2

] E[R

C1

i

T

1

, C

2

] +E[R

C1

i

T

1

, C

2

]

E[R

T2

i

T

2

, C

1

] = E[R

T1

i

R

C1

i

T

1

, C

2

]

. .

The treatment effect

+E[R

C1

i

T

1

, C

2

] E[R

T2

i

T

2

, C

1

]

. .

Selection bias

. To get

unbiased estimates, we must ensure: E[R

C1

i

T

1

, C

2

] = E[R

T2

i

T

2

, C

1

] This is a strong

assumption. It implies that the expected religiosity of individuals in the within and

outside areas would have been equal if no Pesantren had been established, regard-

less of whether or not there is analternative religious body inthe outside area. Inthe

absence of information on alternative religious bodies, it is likely that the estimates

will underestimate the true effect given negative selection bias.

23

HTI stands for Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia; LDII is Lembaga Dakwah Islam Indonesia

(Indonesia Institute of Islamic Dawah); PERSIS is Persatuan Islam (Islamic Unity).

Pesantren characteristics in Column (2). In Column (3), I include the

interaction term between frequency of religious attendance and

residence location to see whether the role of religiosity in earn-

ings differs between the internal (i.e. within) and external (i.e.

outside) communities. The signicance of coefcients for Loca-

tionmosque attendance =sometimes and Locationmosque

attendance =frequent implies that being involved in religious

activities is more rewarding in the within community.

Next, I split the sample into two categories based on residence

location: within and outside. I nd a mechanism of how religious

attendance matters for earnings. The estimates in Columns (4) and

(5) indicate important roles of two mass organisations, namely

Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) and Muhammadiyah. In Column (4) I include

two dummy variables of the presence of these two organisations

in the community. Both coefcients are positive and signicant.

The two organisations often run entrepreneur development work-

shops, free public clinics, etc. Muhammadiyah is especially known

for providing education and health services (Fuad, 2002). These

activities might affect their members earnings positively. In con-

trast, none of coefcients for religious attendance is signicant in

Column (4). Once I exclude variables on the presence of NU and

Muhammadiyah, the adjusted R-2 decreases by about 5% as had

shown by Column (5) and two dummy variables of religious atten-

dance become signicant. The mechanism does not appear in the

outside community as suggested by Columns (6) and (7). Taken

together, the results suggest that living close to a Pesantren sig-

nicantly increases the effect of frequent religious attendance on

earnings.

24

The presence of NU and Muhammadiyah seems to con-

tribute to the process.

4.2. Robustness check

Results from Section 4.1 might be subject to some possible

sources of bias or limitations of variables. In this section, I focus on

twoaspects, namely religious measures andnon-randomresidence

selection.

One possible source of bias inthe study is the measurement bias.

I use variable on frequency of participating at religious activities

(MOSQUE). However, this proxymaysuffer frompotential bias such

24

Regarding individual characteristics, two variables are signicant: years of

schooling (positive) and when residence ownership status is given by relative

(negative).

R. Permani / The Journal of Socio-Economics 40 (2011) 247258 253

Table 2

OLS earnings equations.

Dependent variable: log(hourly earnings) Pooled sample Within Outside

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7)

1. Religious attendance and residence location

Location (1=within Pesantren area; 0=outside Pesantren area) 0.099 0.023 0.491

*

(0.085) (0.124) (0.198)

HHs mosque attendance =sometimes 0.176 0.291 0.019 0.531 0.598

*

0.085 0.044

(0.170) (0.178) (0.202) (0.230) (0.210) (0.190) (0.208)

HHs mosque attendance =frequent 0.347

*

0.348

*

0.055 0.503 0.500

*

0.03 0.108

(0.142) (0.161) (0.164) (0.258) (0.211) (0.172) (0.168)

Location=1mosque attendance =sometimes 0.540

*

(0.251)

Location=1mosque attendance =frequent 0.530

*

(0.238)

2. Pesantren characteristics

Kyais age 0.005 0.004 0.021

***

0.022

**

0.007 0.004

(0.006) (0.007) (0.002) (0.005) (0.005) (0.008)

Pesantrens year of establishment 0.001 0.002 0.004 0.002 0.002 0.002

(0.003) (0.003) (0.002) (0.003) (0.002) (0.003)

Kyais years of services 0.007 0.006 0.027

***

0.021

*

0.011 0.018

(0.011) (0.010) (0.004) (0.009) (0.005) (0.015)

Do Kyai guide the community? (1=yes; 0=no) 0.268 0.32 0.163 0.177 0.123 0.263

*

(0.163) (0.170) (0.189) (0.184) (0.171) (0.093)

3. Competition effects

The Herndahl index (religious market competition) 0.452 0.429 1.582

**

0.206

(0.343) (0.349) (0.336) (0.131)

An NU-afliated organisation is in the community (1=yes; 0=no) 0.003 0.037 0.959

*

0.321

(0.268) (0.261) (0.344) (0.195)

A Muhammadiyah-afliated organisation is in the community (1=yes; 0=no) 0.441 0.534 1.032

**

0.273

(0.133) (0.155) (0.390) (0.329)

Constant 8.260

***

5.829 5.108 16.948

**

13.537 4.189 4.371

(0.478) (5.511) (5.566) (4.558) (6.899) (5.491) (6.163)

Pesantren xed effects Yes No No No No No No

Control individual characteristics Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Adj-R

2

0.168 0.123 0.127 0.223 0.181 0.091 0.063

Log-likelihood 482.595 430.497 428.657 226.331 233.07 186.045 190.207

No. observations 406 358 358 195 195 163 163

Note: For all columns, standard errors are in parentheses. Standard errors are corrected for clustering at the community. Control individual characteristics include marital

status, age, years of schooling, number of kids aged between 0 and 14.

*

Signicance at the 10% level.

**

Signicance at the 5% level.

***

Signicance at the 1% level.

as gender bias. Such measure might not cause a serious problemfor

religions which require regular services attendance for all mem-

bers such as Protestant Christian or Catholic. But for religions in

which attendance at services is restricted to only some parts of the

groups, the index might cause some bias. One example is on Mus-

limwomen. In Islam, women are recommended to worship (shalat)

at their houses, more specically in their own rooms. In contrast,

worshipping at the mosque is considered obligatory for men. In

addition, Muslim men are attending the mosque at least once a

week to conduct Friday prayer (shalat jumat) giving them, in gen-

eral, a higher frequency than women. Indeed, among Muslim men,

some might believe public religious attendance is not as impor-

tant as what is believed by some other people. I therefore extend

my analysis by conducting factor analysis to allow alternative for

public religious attendance.

25

I consider two additional variables donation among Muslims

(DONATION) and types of preferred nancial institutions (TYPE-

FIN), i.e. whether conventional or Shariah-compliant institutions.

Types of preferred nancial services are chosen due to recent

25

Althoughthestandardfactor analysis as appliedinthis study, is basedonPearson

correlation for continuous data, Vermunt and Magidson (2005) showthat the result

of thelatent class factor analysis (LFCA), whichis specicallydesignedfor categorical

variables, are quite similar to standard factor analysis. In addition, a disadvantage

of LCFA is its parameters are difcult to interpret. This motivates the study to apply

the standard factor analysis.

trends.

26

There have beenincreasing demands for Shariahproducts

in Indonesia in recent years including Shariah nancial instru-

ments. Many argue that the increasing trend is associated with

the increase in religious awareness of Muslim which observes the

importance of implementing Shariah laws in every aspect of life

including the nancial sector. Astudy inBangladeshnds a positive

effect of joining the Shariah micronance program on religiosity

(Rahman, 2008). Furthermore, althoughthe values are not conned

to Muslim, the goodness of donation has been claimed as a man-

ifestation of ones religiosity. Hence, I also consider the altruism

aspect.

Given one advantage of factor analysis is data reduction and

the rst factor has high variance, I limit the number of factors to

one. All variables appear with positive signs as expected. I nd that

the religiosity factor is closely related to mosque attendance given

its highest factor loadings.

27

Ahigh uniqueness number shows that

26

In the survey the respondents are being asked the following questions: Do you

have saving accounts? (1=Yes; 2=No); If Yes, what types of nancial institutions do

you choose to save your money in? (1=conventional bank; 2=a Shariah bank; 3=Baitul

Maal WaTamsil (BMT); 4=cooperatives; 5=others, please specify). Tosimplify, I reduce

the answers into two categories: 0=non-Shariah and 1=Shariah. The non-Shariah

category consists of conventional banks and cooperatives, while the Shariah con-

sists of Shariah banks and BMT.

27

Communality or squared factor loadings shows the proportion of variance of

explanatory variables explained by m factors. Uniqueness can be then obtained by

one minus communality.

254 R. Permani / The Journal of Socio-Economics 40 (2011) 247258

the other two variables ondonationandpreferredtypes of nancial

institutions are not informative.

28

After some preliminary regres-

sion, I nd that religious participation and the factor analysis proxy

performequally. On this basis, I argue that frequency of participat-

ing at religious activities (MOSQUE) as a strong proxy for religiosity

and therefore results from Section 4 are reliable.

I next consider a possibility of non-random residence selection.

My interest is to capture the treatment effect of Pesantren (T) by

using distance to the Pesantren as a proxy. Those who live in the

outside area, about 510kmfromthe Pesantren are assumed as the

control group (C). We may nd the expected average effect of living

close to a Pesantren on religiosity in a population: E[R

T

i

R

C

i

]. But

access to data is only available to capture: D = E[R

T

i

|T] E[R

C

i

|]. In

a large sample, the equation gives the average religiosity of both

groups (the control and the treatment groups) and examines the

difference between religiosity in a community close and far from

Pesantren. Subtracting and adding E[R

C

i

|T] is needed to decom-

pose our results to the treatment effect and selection bias. The

term E[R

C

i

|T] is the expected religiosity of a person living close to

Pesantren (the treatment group) had he not been treated. This is

an unobservable outcome but actually needs to be observed. The

previous equation can be rewritten as follows:

D = E[R

T

i

|T] E[R

C

i

|T] +E[R

C

i

|T] E[R

C

i

|C] = E[R

T

i

R

C

i

|T] +(E[R

C

i

|T] E[R

C

i

|C]) (10)

The rst term is the treatment effect while the second is the

selection bias. The above equation suggests that the unbiasedness

of the regression method would heavily rely on zero selection bias.

This requires: E[R

C

i

|T] = E[R

C

i

|C] implying that the expected reli-

giosity of individual in the within and outside areas would have

been equal if no Pesantren had been established. This implies that

selection to live close to a Pesantren has to be random. But in real-

ity, selectionto live close to a particular Pesantren may represent an

unobservable variable (or a latent index) showing the net benet

of living close to Pesantren. Hence, the use of standard OLS in the

wage equation (or a standard ordered logit model for the religiosity

equation) might yield bias results.

To deal with this issue, my approach is to control non-random

residence selectionbias usingthe Heckmanselectioncriterionterm

in the outcome equation (Heckman, 1979). The term is the inverse

Mills ratio using tted values fromthe rst stage probit model esti-

mating the probability of living close to Pesantren.

29

I estimate the

following Probit model:

Pr[d

ij

= 1] =

0

+

1

X

ij

+

2

Q

j

+

3

W

ij

+

ij

(11)

where d

ij

is equal to one if individual i lives in the within area of

Pesantren j, and 0 otherwise; X

ij

the vector of the head of house-

holds characteristics (marital status, age (and its squared), number

of children, years of schooling and ability to write); Q

j

the vector of

Pesantrenj characteristics and

ij

theerror term.

30

Todiffer between

28

Uniqueness: MOSQUE=0.2808, DONATION=0.9332, TYPEFIN=0.9631.

29

It is important to note that I do not assume causal relationships between the

dependent variable and the right hand side variables. While I assume Pesantrens

characteristics are exogenous (therefore might cause variation in residence selec-

tion), current observations of individual characteristics might not predict exactly the

individuals decisiononmoving to a particular area inthe past. For example, the per-

son might have been staying in the area since he was born, indicating a case where

residence selection is indeed exogenous. However, it is logical to assume that each

individual has a choice to move to other area. Hence, the association between cur-

rent individual characteristics anda decisiontostill live close toa Pesantrenindicates

conformity between the presence of Pesantren and an accommodating environment

to live in.

30

Althoughthesurveyhas awiderangeof Pesantrencharacteristics, alimitednum-

ber of Pesantrenbeingsurveyedcausesomeof thevariables tohavecollinearity. After

some specication checks, I include three Kyai characteristics (age, working expe-

rience and whether the HH guides community in the election) and four Pesantren

characteristics (years of establishment, percentage income from governments and

tuition fees and also whether the Pesantren has a borrowing-lending unit.

Table 3

Heckman-corrected wage equations.

Dependent variable: hourly wage Within Outside

(1) (2)

1. Religious attendance and residence location

HHs mosque

attendance =sometimes

0.529

*

0.094

(0.010) (0.668)

HHs mosque

attendance =frequent

0.502

*

0.014

(0.030) (0.924)

2. Pesantren characteristics

Kyais age 0.021

***

0.008

(0.000) (0.342)

Pesantrens year of establishment 0.004

*

0.002

(0.042) (0.671)

Kyais years of services 0.026

**

0.011

(0.001) (0.142)

Do Kyai guide the community?

(1=yes; 0=no)

0.162 0.117

(0.407) (0.696)

3. Competition effects

The Herndahl index (religious

market competition)

1.627

***

0.131

(0.001) (0.754)

An NU-afliated organisation is in

the community (1=yes; 0=no)

0.986

*

0.41

(0.017) (0.156)

A Muhammadiyah-afliated

organisation is in the community

(1=yes; 0=no)

1.082

***

0.173

(0.000) (0.810)

Constant 16.740

***

4.273

(0.000) (0.611)

Pesantren xed effects No No

Control individual characteristics Yes Yes

The inverse Mills ratio 0.192 0.338

Log-likelihood 226.331 233.07

No. observations 247 215

Note: For all columns, standard errors are in parentheses. Standard errors are cor-

rected for clustering at the community. Control individual characteristics include

marital status, age, years of schooling, number of kids aged between 0 and 14.

*

Signicance at the 10% level.

**

Signicance at the 5% level.

***

Signicance at the 1% level.

the rst-stage regression and the second stage model, I include W

ij

.

It includes an (exogenous) dummy variable of whether the head of

households parents also lived in the same area.

31

Of a long list of

variables included, I only nd being married is positively correlated

to the probability of living close to Pesantren. The positive effect of

marital status might be motivated by individual commitment to

instill religious values in their family life and possibly their chil-

dren. The model can only explain 1.4% of variation in probability of

residing close to Pesantren.

Table 3 re-estimates results from Section 4.1. Overall, the esti-

mates suggest that living close to a Pesantren signicantly increases

the effect of frequent religious attendance on earnings. Pesantren

and community characteristics previously argued as important

31

Analternative determinant of residence selectionis school availability andother

community facilities such as post ofces, hospitals, banks, supermarkets, Internet

kiosk, etc. in the surrounding Pesantren. But the variation between the within and

outside area is almost zero in all Pesantren. It is logical to argue that they will not

be signicant factors of residence choice to differ between religiosity and earnings

in the within and outside areas due to a reasonable distance between Pesantren and

the outside community (approximately 510km). This argument might sound

contradictory to the reason why geographical effect is important for analysis of

religiosity. But I argue that in the community it is very common for children to

travel 510kmto their schools given howtheir parents viewthe value of education.

It is not, however, very common to travel this far to attend religious services on daily

basis and ve times a day.

R. Permani / The Journal of Socio-Economics 40 (2011) 247258 255

0

5

0

1

0

0

1

5

0

R

a

i

n

f

a

l

l

(

m

m

)

i

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

2

0

0

7

1 6 11 16 21 26 31

Rain date

Central_Jakarta North_Jakarta

West_Jakarta South_Jakarta

Tasikmalaya East_Jakarta

0

2

0

4

0

6

0

8

0

R

a

i

n

f

a

l

l

(

m

m

)

i

n

S

e

p

t

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

0

7

1 6 11 16 21 26 31

Rain date

Central_Jakarta North_Jakarta

West_Jakarta South_Jakarta

Tasikmalaya East_Jakarta

Fig. 1. Rainfall data.

Source: Meteorological Climatological and Geophysical Agency (BMKG).

determinants of earnings also appear to be signicant in Table 3

and have similar magnitude to coefcients inTable 2, namely Kyais

age, Kyais experience, the presence of NU and Muhammadiyah.

The results suggest the robustness of our previous ndings on

earnings.

5. What Pesantren characteristics are associated with

higher religious attendance?

The previous section has shown the link between religious

attendance and earnings. One may argue that there exists a

two-way relationship between religious attendance and earn-

ings. In the absence of a strong and exogenous instrument for

religious attendance, I previously examined both earnings and

demand for religious education functions using the OLS method.

Specication checks based on preliminary regressions advise that

the OLS method performs better than the Instrumental Variable

method using selected instruments such as donations to fellow

Muslims, the use of Shariah-compliant nancial methods, views on

Pesantrens roles in the communities, whether the person works in

the religious sector, and some other instruments.

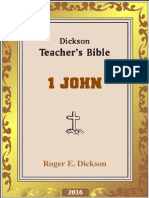

I also examine whether rainfall data is a strong instrument to

explain variation in mosque attendance. There are some possibil-

ities that people stay at home and do not go to religious activities

at religious centres on bad weather days. A study suggests that

higher early-life rainfall has large positive effects on the adult out-

comes of women, i.e. women with 20% higher rainfall (relative to

the local norm) are 0.57cm taller, complete 0.22 more schooling

grades, and live in households scoring 0.12 standard deviations

higher on an asset index (Maccini and Yang, 2009). In this study,

I look at the present rainfall data. People responded to the ques-

tion on how often they attend religious services based on their

current experience (Smith, 1998). Note that the survey was con-

ducted between 20 August 2007 and 12 September 2007, the dry

season in Indonesia. As suggested in Fig. 1, daily rainfall data dur-

ing the period show little variation across the municipalities being

surveyedalthoughthe distance betweenmunicipalities canbe over

100km. Between August 1 and September 30 2007, municipali-

ties where Pesantren are located only experienced 34 rainy days.

Based on the F-statistics in the rst stage regression and the Haus-

man test, the earnings equation using the OLS method is preferred

as it is more efcient.

32

Given that the religious attendance variable is inherently

ordered, I use anorderedprobit model.

33

This takes the explanatory

variables and estimates of the probability of being in each reli-

gious attendance (Mosque attendance) category (never, sometimes,

and very often/frequent). The following regression is estimated for

individual i in the area surrounding of Pesantren j:

Pr(Mosque attendance) = f (X

ij

, d

ij

, Q

j

, V

j

) (12)

In addition to explanatory variables used in the wage equation,

I also include number of working hours per day.

While the coefcients of the ordered probit model only indicate

whether the variables generally improve the frequency of mosque

attendance or not, marginal effects describe howthe probability of

being in each mosque attendance category changes for a one unit

change in a particular variable, or for a discrete jump in a dummy

variable. But to save space, I only report the coefcients. Marginal

effects are reported when they are needed for interpretation.

Table 4 presents the results. Of Pesantren characteristics, the

religious leader or Kyai who is experienced and involved in the

32

Bound et al. (1995) suggest the use of the partial R2 and the F-statistics to qualify

the IV estimates. They nd that if the relationship between instrumental variables

and the endogenous variable is weak, even enormous samples will not eliminate IV

bias. To check whether the instruments are weak, I use critical values (Stock and

Yogo, 2002).

33

While an ordered logit could also be used, the nature of my variables supports

normally, rather than logistically, distributed errors.

256 R. Permani / The Journal of Socio-Economics 40 (2011) 247258

Table 4

Ordered probit: religious attendance.

Dependent variable: religious attendance (0=never; 1=sometimes; 2=very often/always) Pooled sample Within Outside

(1) (2) (3) (4)

Location (1=within Pesantren area; 0=outside Pesantren area) 0.138 0.001

(0.556) (0.998)

1. Pesantren characteristics

Kyais age 0.013 0.004 0.011 0.011

(0.286) (0.686) (0.130) (0.384)

Pesantrens year of establishment 0.007 0.014

**

0.022

***

0.015

*

(0.142) (0.006) (0.000) (0.017)

Kyais years of services 0.023 0.029 0.068

***

0.001

(0.126) (0.071) (0.000) (0.812)

Do Kyai guide the community? (1=yes; 0=no) 0.842

*

1.825

***

2.199

***

1.689

***

(0.022) (0.000) (0.000) (0.000)

Location=1x do Kyai guide the community? (1=yes; 0=no) 0.218

(0.384)

2. Competition effects

The Herndahl index (religious market competition) 0.513 0.506 0.382 1.157

*

(0.096) (0.180) (0.498) (0.020)

An NU-afliated organisation is in the community (1=yes; 0=no) 0.627

*

0.082 0.6 0.775

*

(0.042) (0.803) (0.255) (0.028)

A Muhammadiyah-afliated organisation is in the community (1=yes; 0=no) 1.297

**

0.58 0.157 0.559

(0.005) (0.432) (0.781) (0.685)

Do Kyai guide the community? x the presence of NU-afliated organisation 2.332

***

2.209

***

2.124

***

(0.000) (0.000) (0.000)

Do Kyai guide the community? x the presence of Muhammadiyah-afliated organisation 2.833

**

2.352

***

(0.003) (0.000)

Cut1

Constant 13.88 27.076

**

45.401

***

28.802

*

(0.167) (0.009) (0.000) (0.023)

Cut2

Constant 12.631 25.761

*

43.924

***

27.449

*

(0.210) (0.013) (0.000) (0.029)

Pseudo-R

2

0.126 0.165 0.238 0.193

Log-likelihood 299.153 285.846 141.877 125.873

No. observations 358 358 195 163

Note: For all columns, standard errors are in parentheses. Standard errors are corrected for clustering at the community. Control individual characteristics include marital

status, age, years of schooling, number of kids aged between 0 and 14 and average number of working hours per day. Marginal effects for each category of mosque attendance

can be requested from the author.

*

Signicance at the 10% level.

**

Signicance at the 5% level.

***

Signicance at the 1% level.

community is signicant for increased religious attendance as sug-

gested by the signicant coefcients for Years of services and Do

Kyai guide the community? (1=Yes; 0=No) variable. After I split

the sample into two categories, i.e. within versus outside, it is evi-

dent that the effects of Kyais guidance are greater on the religious

attendance of respondents in the within area. In the within area,

the marginal effects suggest that for a discrete jump in Kyais guid-

ance variable and one unit increase in Kyais years of services, the

probabilityof theindividual attendingthemosqueinthefrequent

category versus the combines sometimes and never attend cat-

egories increase by over 60% and 3%, respectively.

Column (1) of Table 4 shows that the presence of NU and

Muhammadiyahis negativelyassociatedwithprobabilityof beingin

frequent religious attendance category. To some extent, relating to

results from the earnings equation the negative coefcients might

reect the negative effect of higher hourly earnings of respondents

who are members of these two mass organisations. But this result

should be interpreted carefully. After I control for the interaction

term between the presence of NU and Muhammadiyah and the

variable on Kyais guidance, the two coefcients become insigni-

cant; while coefcients for the two interaction terms are negative

and signicant. One possible explanation is that the presence of

religious organisations (other than Pesantren) creates competi-

tion effects such that the role of Kyai becomes less signicant. In

such situation, leaders of religious mass organisations may also

play important roles in affecting community religious participa-

tion. In Column (4), I exclude the interaction term between the

presence of Muhammadiyah and variable on Kyais guidance to

avoid collinearity. The Herndahl index, however, suggests the

presence of alternative religious organisations in the community

is positively associated with religious attendance. This might be

correlated to the nding that the Kyai have less contribution in the

external communitycomparedtotheir roles intheinternal (within)

community.

Taken together, the results suggest that the Kyais role is impor-

tant for community religious participation but the role is to a lesser

extent in the community where more religious institutions present

in the community.

6. Conclusion

The theoretical framework in this study can be used to draw

two hypotheses: (1) religious attendance matters for earnings; (2)

physical and religious distances matter for religious attendance.

Observing the surrounding community of religious organisations,

this study has provided statistical evidence to support the rst

hypothesis and some explanations of how distances might mat-

ter by examining the association between Pesantren and the

households decision-making process relating to religiosity and

earnings.

Overall, the empirical results show the important roles of the

Kyai and religiosity and the effects of these variables are different

R. Permani / The Journal of Socio-Economics 40 (2011) 247258 257

for different communities. First, the empirical results suggest that

living close to a Pesantren signicantly increases the effect of fre-

quent religious attendance on earnings. The presence of NU and

Muhammadiyah seems to contribute to the process. In addition to

the existence of religious benets, there might be network effects

or social effects such that it is benecial for the internal community

to attend the mosque more regularly. Examining the determinants

of religious attendance, the Kyais role is important. But the role is to

a lesser extent in the community where more religious institutions

present in the community such as in the external community.

The result from this present analysis may bring some policy