Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter

Chapter

Uploaded by

minchanmonCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- DKP Završni: Savremenog Diplomatskog PravaDocument93 pagesDKP Završni: Savremenog Diplomatskog Pravafilip lončarNo ratings yet

- Evolution of DiplomacyDocument4 pagesEvolution of Diplomacycheptoowinnie100% (1)

- DiplomacyDocument3 pagesDiplomacyIon VerejanuNo ratings yet

- Diplomacy Is The Art and Practice of Conducting Lecture 1Document42 pagesDiplomacy Is The Art and Practice of Conducting Lecture 1Jeremiah Miko Lepasana100% (1)

- Diplomats and Diplomatic MissionsDocument4 pagesDiplomats and Diplomatic Missionsthe angriest shinobiNo ratings yet

- Subject: Diplomacy Roll No: 04 Name: Sehrish ZamanDocument18 pagesSubject: Diplomacy Roll No: 04 Name: Sehrish ZamanOwais Ahmad100% (1)

- Consular ReviewerDocument15 pagesConsular ReviewerMary Elaine R. NavalNo ratings yet

- The Role of The AmbassadorDocument1 pageThe Role of The AmbassadorAmbassador Timothy L. TowellNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic Law: Internal Public Entities Acting in The Field of International Relations 1. The ParliamentDocument5 pagesDiplomatic Law: Internal Public Entities Acting in The Field of International Relations 1. The ParliamentLavinia GabrianNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic and Consular RelationsDocument57 pagesDiplomatic and Consular RelationsRitesh kumar100% (1)

- Diplomatic and Consular Systems: Dr. Hala A. El RashidyDocument16 pagesDiplomatic and Consular Systems: Dr. Hala A. El RashidyHala Ahmed El-RashidyNo ratings yet

- FOUNDATIONS of DIPLOMACYDocument20 pagesFOUNDATIONS of DIPLOMACYJayson ReyesNo ratings yet

- Handout Fpad Chapter Two-DiplomacyDocument35 pagesHandout Fpad Chapter Two-DiplomacyJemal SeidNo ratings yet

- Jamia Millia Islamia: Topic: Diplomatic AgentsDocument24 pagesJamia Millia Islamia: Topic: Diplomatic AgentsSyed Imran AdvNo ratings yet

- Jamia Millia Islamia: Topic: "Diplomatic Agents"Document28 pagesJamia Millia Islamia: Topic: "Diplomatic Agents"Sushant NainNo ratings yet

- ProtocolDocument31 pagesProtocolAsiongNo ratings yet

- ABC Diplomacy enDocument40 pagesABC Diplomacy envalmiirNo ratings yet

- 7th Lecture Batch 159Document66 pages7th Lecture Batch 159Tooba ZaidiNo ratings yet

- Compiled TextbookDocument174 pagesCompiled TextbookcleenewerckNo ratings yet

- Consulates and Their HistoriesDocument6 pagesConsulates and Their HistoriesMichealaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6 ProtocolDocument3 pagesLecture 6 ProtocolСущева ВалеріяNo ratings yet

- Buku BerridgeDocument67 pagesBuku BerridgeHizkia Dicken DirgantaraNo ratings yet

- ABC of DiplomacyDocument40 pagesABC of DiplomacystrewdNo ratings yet

- Dss 819 ProjectDocument16 pagesDss 819 ProjectOjo Favour EbonyNo ratings yet

- The Right of LegationDocument21 pagesThe Right of LegationjoliwanagNo ratings yet

- International Protocol and EtiquetteDocument10 pagesInternational Protocol and EtiquetteElena CălinNo ratings yet

- ABC of Diplomacy ABC of DiplomacyDocument18 pagesABC of Diplomacy ABC of DiplomacyAudrey Mariel CandorNo ratings yet

- Index GyDocument3 pagesIndex GyWilliam Harper LanghorneNo ratings yet

- Cli Paper Dip Issue92Document22 pagesCli Paper Dip Issue92National Basketball AssociationNo ratings yet

- DiplomacyDocument18 pagesDiplomacyjeevitha ranganathanNo ratings yet

- 14.1 Diplomatic LawDocument37 pages14.1 Diplomatic LawOğuzhan AyasunNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic ImmunityDocument15 pagesDiplomatic Immunitymirmoinul100% (1)

- History and The Evolution of DiplomacyDocument12 pagesHistory and The Evolution of DiplomacyTia Fatihah HandayaniNo ratings yet

- The History of DiplomacyDocument4 pagesThe History of DiplomacyDonasco Casinoo ChrisNo ratings yet

- History and The Evolution of DiplomacyDocument10 pagesHistory and The Evolution of DiplomacyZaima L. GuroNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Peace: Presented By: Ammarah Farhat AbbasDocument67 pagesApproaches To Peace: Presented By: Ammarah Farhat AbbasMuhammad HussainNo ratings yet

- History of Diplomacy - e DiplomatDocument2 pagesHistory of Diplomacy - e DiplomatDana Dela ReaNo ratings yet

- Protocol DepartmentDocument13 pagesProtocol DepartmentarrijalgpNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic AgentsDocument9 pagesDiplomatic AgentsKusum AtriNo ratings yet

- DiplomacyDocument2 pagesDiplomacyVeronica ButoiNo ratings yet

- International Law-II Unit-I Notes of Yuv SharmaDocument11 pagesInternational Law-II Unit-I Notes of Yuv SharmagriffindorsdesktopNo ratings yet

- Vaibhav SM0118060Document17 pagesVaibhav SM0118060Vaibhav GhildiyalNo ratings yet

- Law On Diplomatic AgentsDocument8 pagesLaw On Diplomatic AgentsDanish ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Diplomacy AssignmentDocument10 pagesDiplomacy AssignmentMubashir AliNo ratings yet

- Inr105 Midterm SummaryDocument13 pagesInr105 Midterm Summarymacarambon.fatimaditmaNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic and Consular Systems: Dr. Hala A. El RashidyDocument34 pagesDiplomatic and Consular Systems: Dr. Hala A. El RashidyHala Ahmed El-RashidyNo ratings yet

- Sowerby Diplomatic HistoryDocument16 pagesSowerby Diplomatic Historylaurens van erdeghemNo ratings yet

- Functions of A Diplomatic Mission Basic Functions of A Diplomatic Mission IncludeDocument3 pagesFunctions of A Diplomatic Mission Basic Functions of A Diplomatic Mission IncludeRojakman Soto Tulang100% (1)

- Vienna Convention (Slides Da Aula)Document9 pagesVienna Convention (Slides Da Aula)Anna SantosNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic HistoryDocument2 pagesDiplomatic Historyekkal_dinantoNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic Functions and Duties Chapter 3: Diplomatic Functions and DutiesDocument49 pagesDiplomatic Functions and Duties Chapter 3: Diplomatic Functions and DutiesHaider ShubanNo ratings yet

- Audu DiplomacyDocument10 pagesAudu DiplomacyUseni AuduNo ratings yet

- History WSC 2018Document38 pagesHistory WSC 2018daniyal haiderNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic ImmunityDocument10 pagesDiplomatic ImmunityMaryam75% (4)

- Diplomatic RelationsDocument8 pagesDiplomatic RelationsWiljan Jay AbellonNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic StrategyDocument6 pagesDiplomatic Strategythe angriest shinobiNo ratings yet

- At Home with the Diplomats: Inside a European Foreign MinistryFrom EverandAt Home with the Diplomats: Inside a European Foreign MinistryNo ratings yet

- Motivational Theory PDFDocument36 pagesMotivational Theory PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- 6.nov 13 - NLM PDFDocument16 pages6.nov 13 - NLM PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- Rueda Reading - Psychology - Teacherbeliefs - Accepted - Final PDFDocument37 pagesRueda Reading - Psychology - Teacherbeliefs - Accepted - Final PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- Rail Technical Guide FinalDocument13 pagesRail Technical Guide FinalRidwan Akbar Jak JhonNo ratings yet

- 24.oct .13 NLM PDFDocument16 pages24.oct .13 NLM PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- TECREC 100 001 ENERGY STANDARD VER 1 2 Final PDFDocument37 pagesTECREC 100 001 ENERGY STANDARD VER 1 2 Final PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- 17.oct .13 NLM PDFDocument16 pages17.oct .13 NLM PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- SECTION 20710 Flash Butt Rail Welding: Caltrain Standard SpecificationsDocument8 pagesSECTION 20710 Flash Butt Rail Welding: Caltrain Standard SpecificationsminchanmonNo ratings yet

- 1344249181201-Seniority of Inspectors PDFDocument10 pages1344249181201-Seniority of Inspectors PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

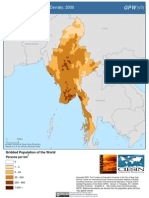

- Population Density, 2000: Gridded Population of The WorldDocument1 pagePopulation Density, 2000: Gridded Population of The WorldminchanmonNo ratings yet

- ORRTUmins310309 PDFDocument11 pagesORRTUmins310309 PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- Ce4017 09Document31 pagesCe4017 09minchanmonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 57Document26 pagesChapter 57minchanmonNo ratings yet

Chapter

Chapter

Uploaded by

minchanmonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter

Chapter

Uploaded by

minchanmonCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Chapt 10

DIPLOMATIC LAW

Contents

Pages

1.1

Historical Introduction

1.2

Establishment of diplomatic relations

1.2.1 Classes of diplomatic agents

1.2.2 Appointment of the Head of mission

14

1.2.3 Appointment of the staff of the mission

17

1.2.4 Presentation of credentials

22

1.2.5 Persona non grata

23

1.2.6 The Diplomatic Corps and Precedence of Diplomats

25

1.3

27

Functions of a Diplomatic Mission

1.3.1 Representation

29

1.3.2 Protection of the Interests of the sending State and

29

its nationals

1.3.3 Negotiating with the Government of the receiving State

30

1.3.4 Ascertaining and Reporting on conditions and

31

developments in the receiving State

1.3.5 Promotion of friendly relation

33

1.4

33

Diplomatic Privileges and Immunities

1.4.1 Theoretical basis of diplomatic immunities

34

1.4.2 The Vienna Convention on the Diplomatic

37

Relations

1.4.3 Immunity from Criminal Jurisdiction

52

1.4.4 Immunity from Civil and Administrative Jurisdiction

57

1.4.5 Waiver of Immunity

63

1.4.6 Freedom of Movement and of Communication

65

Freedom of Movement

1.4.7 Immunity from taxation

68

1.4.8 Other privileges and immunities

73

1.5

Persons entitled to privileges and immunities

74

1.6

Consular Functions and Immunities

77

Diplomatic Law

1.1

Historical Introduction

Diplomacy in the wider sense means the execution of foreign policy. But in the

narrower and more technical sense it refers to the means by which a country's foreign

relations are maintained. Diplomacy or diplomatic relations may be defined as being

the conduct, through representative organs and by peaceful means, of the external

relation of a given State with any other State or States.

( )

( )

Modern diplomacy may take two different forms. Firstly and primarily, there is

the exchange of permanent diplomatic missions. This institution, like the machinery of

the modern State system had its origins in 15

th

century Italy. It has become the

commonest form of diplomatic relations. By agreement, two States may exchange

envoys and establish an embassy in each other's country.

The second form of diplomacy consists of missions which are normally referred

to as special missions, or adhoc diplomacy. This second form may again be divided

into two categories. One consists of visits of made or meetings attended by heads of

State or Government attempting to resolve major political difference, or foreign

ministers representing their States at regular sessions of international organizations.

Besides this class of special missions, conducted by persons having direct political

responsibility, there are what may be termed special missions proper. There are

composed of persons designated for particular task. Besides the traditional example of

the appointment of representation to attend a ceremonial function, such a coronation or

a presidential installation, temporary missions may also be employed or more

immediated political purposes.

()

( )

( )

( )

( )

Special missions are to be distinguished from the official representation of a

state at an adhoc conference convened by a particular Government and form State

representation in an International Organization.

The institution of diplomacy is as old as history itself. Thus Oppenheim says ;

"Legation (Diplomatic relations) as an institution for the purpose of negotiating

between different States, is as old as history whose records are full of examples of

legations sent and received by the oldest nations. And it is remarkable that even in

antiquity where no such law as the modern International Law was known ambassadors

everywhere enjoyed a special protection and certain privileges, although not by law but

by religion, ambassadors being looked upon as sacrosnact".

Oppenheim

History records that in the earliest periods special missions were being

exchanged between the Greek City States. The early Romans too respected the foreign

envoys. The Indian Kings sent their envoys to the Greek Courts, and under Emperor

Ashoker the exchanges of envoys with other countries became more and more

frequent.

Ashoker

The establishment of perimanent missions is of a comparatively recent origin.

Before the 15

th

century the European princes normally sent temporary missions which

were to be terminated as soon as the particular purpose of the mission had been

fulfilled. It was the Italian Repulics and Venice in particular, which were the first to

introduce the practice of maintaining permanent diplomatic missions at each others

capitals.

Italian Repulics and Venice

After the treaty of Westphalia in 1648, which confirmed the principle of balance

of powers in Europe, the establishment of permanent diplomatic missions gradually

became the common practice. Now with the emergence of new nations of Asia and

Africa, diplomatic relations between States become of universal application.

Westphalia

1.2. Establishment of diplomatic relations

Every sovereign State possesses the right of legation. But opening of diplomatic

relations between States is a matter of agreement between the government concerned.

Even though a State may be fully sovereign and recognized by other States, it is very

likely that all states will not be is a position to have diplomatic relations with it.

The actual agreement between the two States expressing their willingness to

enter into diplomatic relations may be in the form of a solemn treaty. It may be also be

more informal, that is, in the form of an exchange of notes between foreign ministers or

between ambassadors posted in a third State.

( )

1.2.1. Classes of diplomatic agents

A Regulation relating to the classification of diplomatic agents was first adopted

at the Congress of Vienna in 1815. It was later supplemented by a Protocol in 1815.

Under these regulations diplomatic agents were divided into four classes:

(1)

Ambassador

(2)

Envoys and Ministers Plenipotentiary

(3)

Ministers resident

(4)

Charge d' Affaires

10

()

()

()

()

This classification is good even today with the exception that Minister Residents

are no longer regarded as heads of mission. The following is the modern classification

embodied in the Vienna Convention, 1961.

"Heads of mission are divided into three classes, namely.

(a)

that of ambassadors or nuncios accredited to Heads of State;

(b)

that of envoys, ministers and internuncios accredited to Heads

of State;

11

(c)

that of Charges d' affairs accredited to Ministers for foreign

Affaires".

()

()

()

Among the three classes of Heads of mission, those ranking the highest are

ambassadors. Their equals are Papal nuncios who are first class envoys accredited by

the Holy See. Ambassadors are considered to be personal representaives of the Heads

of their States, and enjoy special honours. Their chief privilege is that of negotiating

with the Head of the State personally. But this has little value today because all States

have to a certain extent, constitutional Governments and all the important business go

through the hands of a Foreign Secretary.

12

Ambassadors can also claim the title of "Excellency." Besides it is asserted that

they have also the right to ask for an audience from the Head of the State to whom they

are accredited.

"

"

The second class, Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary, to which

also belong the Papal internuncios, are not considered to be personal representatives of

the Heads of their States. Therefore they do not enjoy all the honors of the

Ambassadors. They have not the privilege of meeting with the Head of the State

personally. But otherwise there is no difference between the two classes except that

Ministers Plenipotentiary receive the title of "Excellency" by courtesy only and not by

right.

13

"

"

The third class, charges d' affaries, differs chiefly in one point from the first and

second classes. They are accredited from Foreign Office to Foreign Office, whereas the

other classes are accredited from Head of State to Head of State, Charge's d'affaries do

not enjoy, therefore, so many honours as other diplomatic envoys.

14

1.2.2

Appointment of the Head of mission

Appointment of the Head of a diplomatic mission is made by and in the

name of the Head of the State, though he is usually advised by the Minister for Foreign

Affairs. When the appointment has been provisionally decided upon, the name of the

envoy has to be submitted to the Government of the receiving State as soon as possible.

This procedure is important because the agreement of the receiving State is essential

for the validity of such an appointment. The Vienna Convention on the Diplomatic

Relations, 1961 states as follows:

1.

The sending State must make certain that the agreement of the receiving State

has been given for the person it proposes to accredit as head of the mission to

that State.

2.

The receiving State is not obliged to give reasons to the sending State for a

refusal of agreement.

15

()

()

Therefore every State has the right to refuse any particular individual; whether it

be on the ground of his personal character or of his previous record. There were some

illustrative past instances. Sweden in 1757 refused to accept the British envoy

Goodrich because after his appointment he had visited a prince with whom Sweden

was at war. In 1891, China refused to accept the. Minister Mr.Blair as he was reported

to have bitterly abused China in the Senate. In 1885 Italy refused to receive Mr.Koily

as the U.S Minister without assigning reason.

Goodrich

16

Mr Blair

Mr Koily

With regard to the appointment of the head of mission, the normal practice today

is to submit the name of the person beforehand to the Head of the State to whom he is

proposed to be accerdited. This is done confidentially and the view of the receiving

State are also communicated confidentially. Until the agreement is received, the

practice is not to make any pronouncement of the appointment. In the case of

appointment to the headship of a mission newly opened, the communication is usually

sent by the Foreign Minister of one State to the Foreign Minister of the other. In the

case of existing mission the request for agreement is either sent through the retiring

envoy or through the chang'ed affaires interim.

17

()

A state may accredit a head of mission to more than one State, unless there is

express objection by any of the receiving States. This is the occasional practice of some

developing States for reasons of economy.

1.2.3. Appointment of the staff of the mission

The staff of a mission is broadly divided into two categories namely:

(1)

diplomatic staff and

18

(2)

non-diplomatic staff

()

()

()

In addition, there are various types of attache' who perform certain specialised

functions in the missions, very often the attache's are equated with members of the

diplomatic staff.

Diplomatic Staff

The diplomatic staff are those who perform functions of a political and

diplomatic character. They fall within the categories of Minister, Consellor, First

Secretary, Second Secretary and Third Secretary.

19

With the increase in the number of diplomatic missions located in various parts

of the world and the changes brought about in the functions of diplomatic officers the

need for specialization was strongly felt. It led to the formation of Career Diplomatic

Services. Today it has become almost the invariable practice to restrict appointments in

the diplomatic staff to career diplomats.

Britain, the U.S., Japan and most of the Western countries have maintained such

career services for many years ago. Most of the newly independent countries have

followed the same practice.

20

Non-diplomatic staff

Non-diplomatic staff consists of various categories of personnel who do not

possess the diplomatic status. They range from office superintendents and registrars to

stenographers, typists, clerical assistants, cypher clerks, messengers and chauffeurs.

In the case of appointment of non-diplomatic staff also, the right of making

appointment belongs to the sending state. The receiving State may object to the

appointment of any objectionable individual. However those persons cannot be

declared person non-grata as that term applies only to diplomatic officers.

21

Attache's

As attache'is a person who is attached to the staff of an ambassador.

One of the modern trends in diplomatic practice has been the appointment of a number

of attache's to deal with specialised types of work. Such persons are by agreement

between the sending and the receiving state usually given diplomatic rank. To this class

falls:

(1)

the Military, Air or Naval Attache's

(2)

the Commercial Attache's

(3)

the Press and Information Attache's or Cultural Attache's

The main function of service attache's or military air or naval attache's is

to liaison between the armed forces of the two countries. These persons do not come

under the Foreign Office, though they are subjected to the control of the head of the

mission.

()

()

22

()

()

Commercial Counsellors, Secretaries or Attache's, howsoever they may be

designated, play an important role in promoting trade and commerce between the

sending and the receiving States.

( )

1.2.4 Presentation of credentials

If the head of the mission is one of the first or second class, it is the duty of the

Head of the State to receive him solemnly in an audience with all the usual ceremonies.

For that purpose, the envoy sends a ture copy of his credentials to the Foreign Office,

which arranges for him a special audience with the Head of the State, when he delivers

person his sealed credential.

The letters of credence or credentials as they are

23

frequently called are signed by the Head of the sending State and addressed to the Head

of the receiving State.

()

1.2.5 Persona non grata

The Latin term persona non-grata means person not acceptable. It is always

open to the government of the receiving State to declare a diplomat persona non grate

even after his reception. Upon such declaration, the diplomat ceases to function in that

State, and he must leave the country. The sending State is bound to recall him.

Person

non-grata

24

Declaration of persona non grata has been made in cases where a diplomat had

been found taking part in intelligence or espionage activities, or of harbouring foreign

agents, and allowing them to carry on their activities from the premises of the

diplomatic mission, or of wrongfully giving shelter to fugitives from justice.

( )

There were controversies as to whether a state was bound to give reasons for

declaring a diplomat "persona non grata".

But the position has now been settled

follows:

in the Vienna Convention, 1961, as

25

"The receiving State may at any time and without having to explain its

decision, notify the sending state that the head of the mission or any member of the

diplomatic staff of the mission is persona non grata or that any other member of the

staff of the mission is not acceptable. In any such case, the sending State shall, as

appropriate, either recall the person concerned, or terminate his functions with the

mission.....".

()

( )

1.6.6 The Diplomatic Corps and Precedence of Diplomats

All the diplomatic envoys accredited to the same State form, according to a

diplomatic usage, a body which is styled the "Diplomatic Corps". The head of this

body is called "Doyen" or "Dean".

26

()

The Diplomatic Corps comprises all heads of missions and their diplomatic staff

including counselors, secretaries and attache's. In almost all capitals a list of persons

who are included in the diplomatic body is compiled by the Foreign Office and

pulished from time to time. This is called the "diplomatic list". This is generally done

from the information supplied to the Foreign Office by the diplomatic missions

themselves. The entry of a person's name in the diplomatic list is often accepted as the

conclusive evidence of a person's having that status.

27

1.3 Functions of a Diplomatic Mission

As regards the functions of a diplomatic mission, no precise definition exists or

has been evolved. However, the Vienna Convention gives a non-exhaustive defination,

distinguishing the five main functions of a diplomatic mission in the following terms:

( )

Vienna Convention

(1)

The functions of a diplomatic mission consist inter alia in:

(a)

representing the sending State in the receiving State

(b)

protecting in the receiving State the interest of the sending State and of its

national, within the limits permitted by international law.

(c)

negotiating with the Government of the receiving State.

(d)

ascertaining by all lawful means conditions and developments in the

receiving State, and reporting thereon the Government of the sending

State;

28

(e)

promoting friendly relations between the sending State and the receiving

State, and developing their economic, cultural and scientific relations.

(2)

Nothing in the present Convention shall be construed as preventing the

performance of consular functions by a diplomatic mission".

()

()

()

()

()

()

29

1.3.1 Representation

The First and foremost function of envoy is to represent the sending State in the

receiving State and to act as the channel of official relations between the governments

of the two States. He is the official agent and the mouthpiece of his government.

1.3.2 Protection of the Interests of the sending State and its nationals

Protection of the interests of the sending State and of its nationals is one

of the primary duties of an envoy. The interests of his home State are entrusted to his

care and an envoy has to be ever vigilant in order to protect such interestes in the State

to which he is accredited. An envoy has to take possible steps and precautions to that

any existing advantage which his government in his nationals may enjoy in the State of

his residence and jeopardized.

30

1.3.3

Negotiating with the Government of the receiving State

Whenever a government wished to enter into a treaty with another, the formal

negotiations are often preceded by preliminary soundings and explanatory talks which

have to be conducted by the diplomatic agent. He is to act cautiously and tactfully

when the proposed treaty is of a political character, such as a treaty of friendship or

mutual aid.

31

( )

Similarly, it is diplomatic envoy who has negotiated with the government of the

receiving state in all matters where his government wishes to represent a claim on

behalf of one of its nationals.

1.3.4 Ascertaining and Reporting on conditions and developments in the

receiving State

In former times, diplomats were often considered to be official spies. But in

modern times, a diplomat's right to report to his government on the conditions in the

State to which he is accredited is not only regarded as legitimate but is also considered

to be in the mutual interest of nations. The welfare of one State has been closely linked

with the welfare of others. Thus the political instability or upheaval in one country is

likely to crate problems for other States as from mass movement of population and

influx of refugees.

32

( )

A diplomat has a heavy responsibility. By interpreting correctly the political

conditions in the State to which he accredited, he may be able to help in averting a

crucial situation which might otherwise lead to a threat or breach of peace.

( )

33

1.3.5

Promotion of friendly relation

Since the establishment of the United Nations, it has been recognized that an

envoy's functions must include the active promotion of understanding between the

sending and receiving States and their peoples. An effective media in this respect is

through information bulletin issued weekly or fortnightly. Exchange of good will

missions and cultural delegations has also been and important feature for the promotion

of friendly relations.

1.4

Diplomatic Privileges and Immunities.

34

Under customary international law, diplomats have been allowed certain

privileges and immunities. This is forded on common usage, tract consent and

reciprocity.

1.4.1 Theoretical basis of diplomatic immunities

There are various theories regarding the legal basis of diplomatic immunities.

(a)

Exterritoriality

The first and oldest is the doctrine of exterritoriality. Under this theory, the

premises of a diplomatic mission are outside the territory of the receiving State and

represent a sort of extension of the territory of the sending State. Similarly, an

ambassador who represents by fiction the a actual person of his sovereign must be

35

regarded by a further fiction as being outside the territory of the State to which he is

accredited.

(b)

Representative character

According to this theory, the diplomatic agent as representing a sovereign State

owes no allegiance to the State to which he is accredited and as such he could not be

subjected to the laws and jurisdiction of the receiving State.

36

(c) Functional necessity

The modern tendency is to allow immunities on the basis of "functional

necessity" that is to say, the immunities are to be granted to the diplomats because they

could not exercise their functions perfectly unless they enjoyed such privileges.

" "

It is on the basis of this functional necessity that the Vienna Convention States

in the preamble that:

"The purpose of such privileges and immunities is not to benefit

individuals but to ensure the efficient performance of the functions of diplomatic

missions as representing States"

Vienna

"

37

1.4.2

The Vienna Convention on the Diplomatic Relations 1961

The practice of the States over a number of years has varied much on the scope

and extent of diplomatic immunity. A good deal of conflict arose in the past. Therefore,

the United Nations referred this problem to the International Law Commission as being

a priority topic for progressive development and codification.

Though the draft Convention prepared by the Commission dealt with permanent

diplomatic missions, the Special Rapporteurs also studied on other forms of diplomatic

relations, that is to say. So- called "ad hoc diplomacy", covering itinerant envoys or

roving envoys, diplomatic conferences and special missions sent to a state for limited

purposes.

38

( )

In pursuance of the report of the International Law Commission, the General

Assembly decided to convene a conference of plenipotentiaries. The U.N Conference

on Diplomatic Intercourse and Immunities met in Vienna in 1961. It was attended by

delegates from 81 States.

The Conference adopted a Convention untitled "the Vienna Convention on

Diplomatic Relations" covering most major aspects of permanent diplomatic relation

between States. The Convention entered into force on April, 24, 1964.

"

"

39

Personal inviolability

Article 29 of the Vienna Convention provides:

" The person of a diplomatic agent shall be inviolable. He shall not be

liable to any form of arrest or detention. The receiving State shall treat him with due

respect and shall take all appropriate steps to prevent any attack on his person, freedom

or dignity".

"

"

( )

40

It implies that the receiving State is obliged to afford a high degree of protection

to the person of the diplomatic agent. If an act violating the immunity of the envoy is

committed by a public official adequate reparation is due.

Domestic legislations of several countries provide specifically for punishment

for infringement of the personal inviolability of a diplomal. Thus, according to English

Criminal Law, everyone is guilty of a misdemeanor who, by force are personal

restraint, violates any privilege conferred upon diplomatic agents.

The U.S Supreme Court held that:

"The person of a diplomat is sacred and inviolable and whoever offers

any violence hurts the common safety and well-being of nations; he is guilty of a crime

against the whole world".

41

US

"

It is , however, expected that a diplomat will pay due regard to the laws of the

maintenance of public order and safely. The best guarantee of the diplomat's immunity

is the correctness of his own conduct.

In times of war, a special obligation towards a diplomatic agent is owed. Every

endeavour must be made not only to protect his person and property, but the State must

also facilitate the departure of the diplomat from its territory.

42

Inviolabllity of the Premise of Mission

The principle of inviolability of the premises of the mission and that of the

residence of the envoy has been treated on the same footing.

Article 22 of the Vienna Convention provides

1.

The premises of the mission shall be inviolable. The agents of the receiving

State may not enter them except with the consent of the head of the mission.

2.

The receiving State is under a special duty to take all appropriate steps to

protect the premises of the mission against any intrusion or damage and to

prevent any disturbance of the peace of the mission or impairment of its

dignity.

3.

The premises of the mission, their furnishings and other property thereon and

the means of transport of the mission shall be immune from search,

requisition, attachment or execution".

43

( )

( )

()

The "premises of the mission" are the buildings or parts of buildings and the

land ancillary thereto, irrespective of ownership, used for the purpose of the mission

including the residence of the head of the mission.

( )

The premises are deemed to include all buildings appurtenances, garden and the

car park. The term "the means of transport of the mission" applies to carriages, motor

cars, boats and aeroplanes if used fro diplomatic purposes.

44

" "

Article 30 of the Vienna Convention States:

1.

The private residence of a diplomatic agent shall enjoy the same

inviolability and protection as the premises of the mission.

2.

His papers, correspondence and, except as provided in paragraph 3 of

Article 31, his property shall likewise enjoy inviolability.

The principle of inviolability requires that the premises of the mission shall in

all cases be inaccessible to officers of justice, police, revenue and custom. Unless the

head of the mission gives an express authorization, no public official shall enter the

premises nor exercise any functions therein; thus no writ nor summons may be served

within the premises.

45

()

Cases of emergency

Practice shows that there may be occasions when the diplomatic agent may

himself require the assistance of the local authorities, for example, to prevent a fire, to

arrest a criminal and the like.

On the other hand, there appears to be some difference of opinions as to whether

the diplomatic premises can be entered by local officials in cases of extreme

emergency such as civil commotion, aerial bombardment, fire or other national

calamity. In the International law Commission the prevailing view was that such a

power in the hands of the receiving State may well lead to abuse.

46

()

Surrender of criminals taking shelter within the premises

Diplomatic immunity allows no justification for an envoy to give shelter to a

criminal within the permises. If a person wanted by the authorities on a criminal charge

takes refuge within the premises, he should either be surrendered to the police or the

authorities should be permitted to apprehend the offender within the premises. If a

crime is committed within the permises, the offendes should be handed over to the

local authorities.

()

47

The receiving State may also protect if a private person is detained within a

foreign embassy, as such an act will amount to an abuse of the right of inviolability of

the premises. In the case"Sun Yet Sen" a political refugee from china, who was

detained within the Chinses legation in London, the Foreign Office intervened with the

resule that he was released.

"Sun

Yet

Sen"

The Vienna Convention in Artical 41(3) also provides:

"The permises

of the mission must not be used in any manner

incompatible with the functions of the mission as laid down in the present Convention

or by other rules of general international law".

()

"

48

"

Exterritorility and the so-called diplomatic asylum

The oldest theory of diplomacy is the theory of exterritoriality which implies

that the premises of the mission in theory are outside the territory of the receiving

State. However, according to Oppenheim, exterritoriality is a fiction only, because

diplomatic premises are in reality not without, but within the territory of the receiving

State.

Oppenhein

The so-called diplomatic asylum means the right of envoys to grant asylum,

within the boundaries of their residential quarters, to any individual who took refuge

there. In recent times, the practice of States has been to discontinue such right of

49

asylum. Many States including the U.S.A have expressly taken the stand that no such

right exists in international law.

In the Asylum Case, the ICJ observes:

"Diplomatic asylum withdraws the offender from the jurisdiction of the

territorial State and constitutes an intervention in matters which exclusively within the

competence of that State. Such derogation from territorial sovereignty cannot be

recognized.

Asylum

50

It may however be noted that the practice of granting asylum is still recognised

in some of the Latin American States, particularly those which are parties to the

Havana Convention of 1928 and the Montevideo Convention of 1933 on Political

Asylum. In these cases, the position is different because the right to grant asylum, and

the duty by the territorial State to respect it, are expressly recognized in a treaty.

Havana Montevideo

A distinction must be drawn between asylum and cases of "temporary refuge" in

times of grave political emergency or in the most compelling consideration of

humanity. The head of a mission is not obliged to prevent a refugee from entering and

taking shelter within the permises of the mission. Temporary refuge or shelter can be

granted to refugees if they are in imminent peril of their lives or to save them from mob

violence or hostilities. A person who has taken refuge must however, be handed over to

the local authorities if he is accused of a criminal charge and a warrant of arrest has

been issued by competent authorities of the receiving State.

51

( )

( )

( )

Inviolability of Archives

Article 24 of the Vienna Convention provides:

"The archives and documents of the mission shall be inviolable at any

time and wherever they may be".

Venna

''

52

Thus the Convention recognizes the inviolability not only of the archives but

also of documents irrespective of their physical whereabout.

Convention

1.4.3 Immunity from Criminal Jurisdiction

Immunity from criminal jurisdiction is the most important consequence of the

personal inviolability of a diplomat. This immunity is absolute and he cannot under any

circumstances be tried or punished by the local criminal courts of the State to which he

is accredited. This complete exemption of a diplomat from criminal jurisdiction is fully

justified by the requirement of his functions otherwise the inviolability of his person

could hardly be guaranteed. The authorities on international law appear to be

unanimous on this questions. This principle has also been incorporated in Article 31 of

the Vienna Convention as follows:

"A diplomatic agent shall enjoy immunity from the criminal jurisdiction

of the receiving State".

53

''

''

It is true that a diplomat is not under the jurisdiction of the receiving State. But

this does not mean that he must have a right to do what he likes. In fact, he is under an

obligation to respect laws of the receiving State. In this connection, Article 41(1) of the

Vienna Convention Says;

"Without prejudice to their privileges and immunities, it is the duty of all

persons enjoying such privileges and immunities to respect the laws and regulations of

the receiving State. They also have a duty not to interfere in the internal affairs of that

State".

54

In case a diplomat acts and behaves otherwise, and disturbs the internal order of

the States, the latter will certainly request his recall, or send him back at once.

( )

The basic principle is that a diplomat is completely immune from the local

criminal jurisdiction. If such is the case; what will be the remedy for a victim of the

crime committed by a diplomat? There will be two alternative courses to be pursued.

55

Firstly; although exempt from the jurisdiction of the receiving State, a diplomat

remains subject to the jurisdiction of his own State. In the classic judgement of

"Dickinson v.Del Solar".

"Diplomatic privilege does not import immunity from legal liability, but

only exemption from local jurisdiction."

''

Dickinson

v.Del

Solar

"

In this regard, the Vienna Convention express, in Article 31(4), as follows: State

does not exempt him from the jurisdiction of the sending State."

Vienna

Converntion

()

56

Therefore, it is possible for an aggrieved plaintiff to carry the battle to a forum

where the defendant cannot claim any special status, that is a court of the sending State.

But there may be many practical and often some legal, obstacles.

The second alternative is more common. The aggrieved citizen first writes to the

diplomat concerned. If he fails to obtain redress, the citizen may then address himself

to the head of the mission. At that stage he may also try to persuade the foreign

ministry of his country to take up the matter. Normally the latter will be reluctant to

intervene on the ground that their action may be harmful to friendly relations between

the two States. If the ministry is prepared to pursue the claim it may either seek to

obtain an admission of liability and payment of any sums due, or waiver of the

immunity so that the case may be settled by the competent court.

57

( )

If the negotiations through diplomatic channels do not succeed, the receiving

State may possibly declare the diplomat person non grata.

1.4.4 Immunity from Civil and Administrative Jurisdiction

Article 31 of the Vienna Convention provides:

1.

...........He shall also enjoy immunity from its civil and administrative

jurisdiction except in the case of:

(a)

a real action relating to private immovable property situated in the

territory of the receiving State; unless he holds it on behalf of the sending

State for the purposes of the mission;

58

(b)

an action relating to succession in which the diplomatic agent is involved

as executor, administrator, heir or legatee as a private person and not on

behalf of the sending State;

(c)

an action relating to any professional or commercial activity exercised by

the diplomatic agent in the receiving State outside his official functions.

2.

A diplomatic agent is not obliged to give evidence as a witness.

3.

No measures of execution may be taken in respect of a diplomatic agent except

in the cases coming under sub-paragraphs(a), (b) and (c) of paragraph 1 of this

Article, and provided that the measures concerned can be taken without

infringing the inviolability of his person or of his residence."

Vienna convention

1.

()

()

59

()

( )

()

()

()

()

Therefore, it is clear that with regard to civil and administrative jurisdiction,

diplomatic agents cannot enjoy absolute immunity. Their immunity is subject to three

limited exceptions.

()

60

In principle a diplomatic agent is employed for that purpose and no other. To

safeguard this principle the Vienna Convention expressly provides in Article 42 that:

"A diplomatic agent shall not in the receiving State practice for personal

profit any professional or commercial activity."

Vienna Convention

''

''

It is clear that such professional and commercial activities are entirely

inconsistent with the position of a diplomatic agent and consequently the would be

declared person non grata. Therefore, it is a surprise to incorporate exception in Article

31. The explanation is that the prohibition and commercial activities, in Article 42

extends only to diplomats and not to other staff or their respective families. Thus the

family of a diplomat would have complete exemption in respect of their professional or

commercial activities if this exception were not included.

61

( )

The occasions for civil action against a diplomat may arise in a number of

circumstances, such as non-payment of debts or tradesman's bills for articles supplied

for his consumption, non-payment of rent or violation of the conditions of a lease,

recovery of their charges or repair bills and compensation for loss or injury caused to a

person or property due to motor car accidents. Since these types of case will not be

covered by the exceptions mentioned in the Vienna Convention, no suit can be

maintained in local courts in respect of such claims.

( )

( )

( )

( )

62

( )

Vienna Convetion

The usual procedure which is adopted is for the aggrieved person to approach

the Protocol Division on of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs with the full particulars of

the claims. If the Ministry is satisfied with the genuineness of a claim, if will approach

the head of the mission of the diplomat concerned for settlement of the claim. Any

diplomatic agent who is anxious to maintain the reputation of his country will not be

slow to respond to such a request. In extreme cases, however, when a diplomat persists

in abuse of his position by non-payment of his debts or just dues and by taking shelter

behind his diplomatic immunity, the government of the receiving state may request his

recall.

63

( )

1.4.5 Waiver of Immunity

It is now well recognised that the immunity of a diplomatic agent can be waived.

The provisions of the Vienna Convention in this respect are as follows:

1.

The immunity from jurisdiction of diplomatic agents of

persons enjoying immunity under Article 37 may be waived by the

sending state.

2.

waiver must always be expressed.

3.

The initiation of proceedings by a diplomatic agent or by a

person enjoying immunity from jurisdiction under Article 37

shall preclude him from invoking immunity from jurisdiction

in respect of any counter-claim directly connected with the

principal claim.

4.

Waiver of immunity from jurisdiction in respect of civil or

administrative proceedings shall not be held to imply waiver

of immunity in respect of the execution of the judgment, for

which a separate waiver shall be necessary".

64

It may be observed that "the immunity which the diplomat possesses is not his

personal prerogative but the immunity of his government, and consequently it is for the

sending state to decide whether the immunity of the diplomat should or should not be

waived on a particular occasion. The diplomat cannot himself waive his immunity

without the permission of his government, nor can be object if his government decides

to waive his immunity".

65

( )

1.4.6. Freedom of Movement and of Communication

Freedom of Movement

The right of an envoy to move about freely in the territory of the receiving state

would appear to be one of the essentials to effective functioning of his mission. Here is

the relevant provision of the Vienna Convention.

"Subject to its law and regulations concerning zones entry into which is

prohibited or regulated for reasons of national security, the receiving state shall ensure

to all members of the mission freedom of movement and travel in its territory".

66

Freedom of communication

It has been an accepted principle of international law that for the proper

discharge of his duties, and hence as a necessary incident of the right of legation, an

envoy should be entitled to correspond freely and in all secrecy with his own

government.

67

Article 27 of the Vienna Convention state, inter alia;

1.

The receiving state shall permit and protect free communication on the part of

the mission for all official purpose. In communicating with the government and

the other missions and consulates of the sending state, wherever situated, the

mission may employ all appropriate means, including diplomatic couriers and

messages in code or cipher. However, the inission may install and use a wireless

transmitter only with the consent of the receiving state.

2.

The official correspondence of the mission shall be inviolable. Official

correspondence means all correspondence relating to the mission and its

functions.

3.

The diplomatic bag shall not be opened or detained.

4.

The packages constituting the diplomatic bag must bear visible external marks

of their character and may contain only diplomatic documents or articles

intended for official use.

( )

68

( )

1. 4.7. Immunity from taxation

Fiscal immunities of a diplomatic mission may be divided into four branches.

The first relates to the exemption from dues and taxes in respect of premises.

Article 23 reads:

69

1. The sending state and the head of the mission shall be exempt from all national,

regional or municipal dues and taxes in respect of the premises of the mission,

whether owned or leased, other than such as represent payment for specific

services rendered ...................... ..........................................................................."

( )

The exemption applies irrespective of whether the premises are owned by the

sending state, or, are leased by it.

The second deals with the fees and charges levied by a mission for various

services such as granting of visas, authentication of documents and other notarial acts.

The universally accepted rule is that all such fees and charges are exempt from local

taxation since they belong to the sending state itself and on the principle that par in

parem non habet imperium. This rule is recognised in Article 28 in the following terms:

"The fees and charges levied by the mission in the course of its official

duties shall be exempt from all dues and taxes".

70

''

The third one concerns with personal emoluments of a diplomatic agent. Article

34 reads:

"A diplomatic agent shall we exempt from all dues and taxes, personal or

real, national, regional or municipal, except:

(a) indirect taxes of a kind which are normally incorporated in the price of goods or

services;

(b) dues and taxes on private immoveable property situated in the territory of the

receiving state, unless he holds it on behalf of the sending state for the purposes of the

mission.

(c) estate, succession or inheritance duties levied by the receiving state, subject to the

provisions of paragraph 4 of Article 39.

71

(d) dues and taxes on private income having its source in the receiving state and capital

taxes on investments made in commercial undertaking in the receiving state;

(e) charges levied for specific services rendered;

(f) registration, court or records fees, mortgage due and stamp duty, with respect to

immovable property, subject to the provisions of Article 23.

( )

( )

()

()

()

72

()

()

()

()

The last one deals with exemption from payment of custom duties. The

following is the relevant provision of the Vienna Convention:

The receiving state shall, in accordance with such laws and regulations as it may

adopt, permit entry of and grand exemption from all customs duties taxes and related

charges other than charges for storage, cartage and similar services, on:

(a)

articles for the official use of the mission;

(b)

articles for the personal use of a diplomatic agent or members of his

family forming part of his household, including articles intended for his

establishment.

73

()

()

()

1.4.8 Other privileges and immunities

The mission and its head shall have the right to use the flag and emblem

of the sending state on the premises of the mission, including the residence of the head

of the mission, and on his means of transport.

74

A diplomatic agent shall with respect to services rendered for the sending state

be exempt from social security provisions which may be in force in the receiving state.

1.5

Persons entitled to privileges and immunities

The extend of the privileges and immunities enjoyed by the personal of a

diplomatic mission varies according to the category to which a person belongs. The

personal of a diplomatic mission may be divided into four categories. They are:

(a)

diplomatic agents and their families;

(b)

administrative and technical staff of the mission and their families;

(c)

service staff of the missoin, and

(d)

private servants.

75

()

()

()

()

Diplomatic agents and their families

A diplomatic agent is the head of the mission or a member of the diplomatic

staff of the mission. The members of the diplomatic staff are the members of the staff

of the mission having deplomatic rank. They include the counsellors, the secretaries

and attaches. Diplomatic agents are entitled to be accorded all the immunities and

privileges mentioned above.

( )

76

"The members of the family of a diplomatic agent forming part of his

household shall, if they are not nations of the receiving state, enjoy the privileges and

immunities specified in Articles 29 to 36." This means that they are entitled to

privileges and immunities to the same exten as diplomatic agents. It is difficult to

define precisely the expression member of the family. Nevertheless, the spouse and

minor children are universally regarded as members of the family.

77

1.6

Consular Functions and Immunities

Consular relation is of a much more ancient origin than permanent diplomatic

missions. It may be said to be a product of international trade and commerce.

The establishment of consular relations between states takes place by mutual

consent, unlike the case of a diplomatic mission. Consulates may be established in

different regions of a country. The very nature of the functions of a consulate

neccessitates establishment of consular offices in areas where trade and industry are

concentrated.

Consular functions are exercised by consular posts. A consular post may be

established in the territory of the receiving state only with that state's consent. The seat

78

of the consular post, its classification and the consular district shall be established by

the sending state and shall be subject to the approval of the receiving state.

Heads of consular posts are divided into four classes, namely:

(a)

Consuls-general;

(b)

Consuls;

(c)

vice-consuls;

(d)

consular agents

()

()

()

()

79

The Head of consular post is appointed by the sending state. He shall be

provided with a document known as the consular commission". If the receiving state

agrees to the appointment, it would an "exequatur" admitting the person concerned to

the exercise of his functions head of a consular post in the territory of the receiving

state. In many states the exequatur is granted by the head of the state if the consular

commission is signed by the head of the sending state and by the Minister for Foreign

Affairs in other cases.

80

Consular functions

By the end of the last century virtually all countries had established consular

services, and consular law and practice had attained a high degree of uniformity.

Consular service in most countries was separate from the diplomatic service although

both were controlled by the foreign ministry. The close interrelation between

diplomatic and consular functions soon led some states to amalgamate the two careers

into a single foreign service. France, Italy, Japan, Norway, the Soviet Union. and the

United States were among the first to take this step, and by now almost all countries

have done so.

France, Italy, Japan, Norway, the

81

Soviet

Union

the

United

States

The Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, Consisting of 79 articles, was

adopted on 24 April 1963. The Convention came into force on 19 March 1967. Article

3 of the Vienna Convention provides:

"Consular functions are exercised by consular posts. They are also

exercised by diplomatic mission in accordance with the provision of the present

convention."

''

''

This article clearly confers "dual diplomatic-consular status" to individuals

assigned to diplomatic missions. Thus it is usual to designate a diplomatic officer as

first Secretary and Consul General or as Second Secretary and Consul or as Third

Secretary and vice Consul.

82

( )

()

Unlike diplomats, consuls do not represent states in the totality of their

international

relations,

and

they

are

not

accredited

to

the

host

state.

Article 5 of the Vienna Convention on Consular Relation, 1963 enumerates

consular functions in long list.

They include, inter alia,

(1)

Protecting the interests of the sending state and of its nationals, both

individuals and bodies corporate;

(2)

furthering the development, of commercial, economic, cultural and

scientific relations between the sending state and the receiving state;

(3)

issuing passports and travel documents to nationals of the sending state

and visas to persons wishing to travel to the sending state;

(4)

acting as notary and civil registrar;

(5)

safeguarding the interests of nationals of the sending state in cases of

succession mortis causa in the territory of the receiving state;

83

(6)

exercising rights of supervision and inspection in respect of vessels

having the nationality of the sending state, and of aircraft registered in

that state, and in respect of their crews.

Vienna

Convention

()

()

()

()

()

84

()

Consular privileges and immunities

International Law guarantees the observance of diplomatic immunities by all

nations, where-as Consular immunities are based on provisions of treaties and practice

of states. There has been a general reluctance on the part of states to accord diplomatic

privileges to consular officers. Therefore the fundamental distinction between a

diplomat and a consular officer lies in the matter of their privileges and immunities.

85

The most striking difference may be that a consular officer has not as much

personal inviolability as a diplomatic agent.

Consular officers shall not be liable to arrest or detention pending trial, except in

the case of a grave crime and pursuant to a decision of the competent judicial authority.

Consular officers shall not be amenable to the jurisdiction of the judicial or

administrative authorities of the receiving state in respect of acts performed in the

exercise of consular functions. This shall not, however, apply in respect of a civil

action either.

( )

(a)

arising out of a contract concluded by a consular officer, or

(b)

by a third party for damage arising from an accident.

86

()

()

Members of a consular post may be called upon to attend as witnesses in the

course of judicial or administrative proceedings ...........if a consular officer should

decline to do so, no coercive measure or penalty may be applied to him.

( )

( )

According to Article 31 of the Vienna Convention;

1.

Consular premises shall be inviolable to the extent provided in this

Article.

2.

The authorities of the receiving state shall not enter that part of the

consular premise which is used exclusively for the purpose of the work of

the consular post except with the consent of the head of the consular

post."

The consular archives and documents shall be inviolable at all times and

wherever they may be.

87

.

.

88

KEY TERMS

Legation

Congress of Vienna

Ambassador

charge'd affaires

Persona non grata

Diplomatic envoy

Diplomatic immunities

Diplomatic practice

Diplomatic person

Diplomatic privileges

Personal inviolability

Diplomatic asylum

Inviolability of Archives

Administrative jurisdiction

89

Consuls

Local criminal court

90

EXERCISE QUESTIONS

Assignment Questions

1. Trace briefly the history of diplomatic relations.

2. What are the classes of diplomatic agents? Discuss briefly.

3. "The person of a diplomatic agent is inviolable". Discuss.

4. Assess the extent of immunity from criminal jurisdiction of a

diplomatic agent.

5. "A diplomat can enjoy immunity from civil jurisdiction subject to

three exceptions".Discuss.

6. Write about the consular functions.

7. Write about the consular privileges and immunities.

Short Questions

1. Write short notes on any two of the following:

a. letters of credence or credentials

b. person non grata

c. the diplomatic corps

d. waiver of immunity

2.

Mr. X is the son of Mr. Y. ambassador of state A accredited to state.

B.He is living with his father at the ambassadorial residence in State

91

B. Because of his reckless driving his car knocks down a pedestrian

who is seriously injured. The authorities of state B are now preparing

to arrest Mr. X and send him before a competent court for trial.

Advise the authorities of state B.

You might also like

- DKP Završni: Savremenog Diplomatskog PravaDocument93 pagesDKP Završni: Savremenog Diplomatskog Pravafilip lončarNo ratings yet

- Evolution of DiplomacyDocument4 pagesEvolution of Diplomacycheptoowinnie100% (1)

- DiplomacyDocument3 pagesDiplomacyIon VerejanuNo ratings yet

- Diplomacy Is The Art and Practice of Conducting Lecture 1Document42 pagesDiplomacy Is The Art and Practice of Conducting Lecture 1Jeremiah Miko Lepasana100% (1)

- Diplomats and Diplomatic MissionsDocument4 pagesDiplomats and Diplomatic Missionsthe angriest shinobiNo ratings yet

- Subject: Diplomacy Roll No: 04 Name: Sehrish ZamanDocument18 pagesSubject: Diplomacy Roll No: 04 Name: Sehrish ZamanOwais Ahmad100% (1)

- Consular ReviewerDocument15 pagesConsular ReviewerMary Elaine R. NavalNo ratings yet

- The Role of The AmbassadorDocument1 pageThe Role of The AmbassadorAmbassador Timothy L. TowellNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic Law: Internal Public Entities Acting in The Field of International Relations 1. The ParliamentDocument5 pagesDiplomatic Law: Internal Public Entities Acting in The Field of International Relations 1. The ParliamentLavinia GabrianNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic and Consular RelationsDocument57 pagesDiplomatic and Consular RelationsRitesh kumar100% (1)

- Diplomatic and Consular Systems: Dr. Hala A. El RashidyDocument16 pagesDiplomatic and Consular Systems: Dr. Hala A. El RashidyHala Ahmed El-RashidyNo ratings yet

- FOUNDATIONS of DIPLOMACYDocument20 pagesFOUNDATIONS of DIPLOMACYJayson ReyesNo ratings yet

- Handout Fpad Chapter Two-DiplomacyDocument35 pagesHandout Fpad Chapter Two-DiplomacyJemal SeidNo ratings yet

- Jamia Millia Islamia: Topic: Diplomatic AgentsDocument24 pagesJamia Millia Islamia: Topic: Diplomatic AgentsSyed Imran AdvNo ratings yet

- Jamia Millia Islamia: Topic: "Diplomatic Agents"Document28 pagesJamia Millia Islamia: Topic: "Diplomatic Agents"Sushant NainNo ratings yet

- ProtocolDocument31 pagesProtocolAsiongNo ratings yet

- ABC Diplomacy enDocument40 pagesABC Diplomacy envalmiirNo ratings yet

- 7th Lecture Batch 159Document66 pages7th Lecture Batch 159Tooba ZaidiNo ratings yet

- Compiled TextbookDocument174 pagesCompiled TextbookcleenewerckNo ratings yet

- Consulates and Their HistoriesDocument6 pagesConsulates and Their HistoriesMichealaNo ratings yet

- Lecture 6 ProtocolDocument3 pagesLecture 6 ProtocolСущева ВалеріяNo ratings yet

- Buku BerridgeDocument67 pagesBuku BerridgeHizkia Dicken DirgantaraNo ratings yet

- ABC of DiplomacyDocument40 pagesABC of DiplomacystrewdNo ratings yet

- Dss 819 ProjectDocument16 pagesDss 819 ProjectOjo Favour EbonyNo ratings yet

- The Right of LegationDocument21 pagesThe Right of LegationjoliwanagNo ratings yet

- International Protocol and EtiquetteDocument10 pagesInternational Protocol and EtiquetteElena CălinNo ratings yet

- ABC of Diplomacy ABC of DiplomacyDocument18 pagesABC of Diplomacy ABC of DiplomacyAudrey Mariel CandorNo ratings yet

- Index GyDocument3 pagesIndex GyWilliam Harper LanghorneNo ratings yet

- Cli Paper Dip Issue92Document22 pagesCli Paper Dip Issue92National Basketball AssociationNo ratings yet

- DiplomacyDocument18 pagesDiplomacyjeevitha ranganathanNo ratings yet

- 14.1 Diplomatic LawDocument37 pages14.1 Diplomatic LawOğuzhan AyasunNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic ImmunityDocument15 pagesDiplomatic Immunitymirmoinul100% (1)

- History and The Evolution of DiplomacyDocument12 pagesHistory and The Evolution of DiplomacyTia Fatihah HandayaniNo ratings yet

- The History of DiplomacyDocument4 pagesThe History of DiplomacyDonasco Casinoo ChrisNo ratings yet

- History and The Evolution of DiplomacyDocument10 pagesHistory and The Evolution of DiplomacyZaima L. GuroNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Peace: Presented By: Ammarah Farhat AbbasDocument67 pagesApproaches To Peace: Presented By: Ammarah Farhat AbbasMuhammad HussainNo ratings yet

- History of Diplomacy - e DiplomatDocument2 pagesHistory of Diplomacy - e DiplomatDana Dela ReaNo ratings yet

- Protocol DepartmentDocument13 pagesProtocol DepartmentarrijalgpNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic AgentsDocument9 pagesDiplomatic AgentsKusum AtriNo ratings yet

- DiplomacyDocument2 pagesDiplomacyVeronica ButoiNo ratings yet

- International Law-II Unit-I Notes of Yuv SharmaDocument11 pagesInternational Law-II Unit-I Notes of Yuv SharmagriffindorsdesktopNo ratings yet

- Vaibhav SM0118060Document17 pagesVaibhav SM0118060Vaibhav GhildiyalNo ratings yet

- Law On Diplomatic AgentsDocument8 pagesLaw On Diplomatic AgentsDanish ChauhanNo ratings yet

- Diplomacy AssignmentDocument10 pagesDiplomacy AssignmentMubashir AliNo ratings yet

- Inr105 Midterm SummaryDocument13 pagesInr105 Midterm Summarymacarambon.fatimaditmaNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic and Consular Systems: Dr. Hala A. El RashidyDocument34 pagesDiplomatic and Consular Systems: Dr. Hala A. El RashidyHala Ahmed El-RashidyNo ratings yet

- Sowerby Diplomatic HistoryDocument16 pagesSowerby Diplomatic Historylaurens van erdeghemNo ratings yet

- Functions of A Diplomatic Mission Basic Functions of A Diplomatic Mission IncludeDocument3 pagesFunctions of A Diplomatic Mission Basic Functions of A Diplomatic Mission IncludeRojakman Soto Tulang100% (1)

- Vienna Convention (Slides Da Aula)Document9 pagesVienna Convention (Slides Da Aula)Anna SantosNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic HistoryDocument2 pagesDiplomatic Historyekkal_dinantoNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic Functions and Duties Chapter 3: Diplomatic Functions and DutiesDocument49 pagesDiplomatic Functions and Duties Chapter 3: Diplomatic Functions and DutiesHaider ShubanNo ratings yet

- Audu DiplomacyDocument10 pagesAudu DiplomacyUseni AuduNo ratings yet

- History WSC 2018Document38 pagesHistory WSC 2018daniyal haiderNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic ImmunityDocument10 pagesDiplomatic ImmunityMaryam75% (4)

- Diplomatic RelationsDocument8 pagesDiplomatic RelationsWiljan Jay AbellonNo ratings yet

- Diplomatic StrategyDocument6 pagesDiplomatic Strategythe angriest shinobiNo ratings yet

- At Home with the Diplomats: Inside a European Foreign MinistryFrom EverandAt Home with the Diplomats: Inside a European Foreign MinistryNo ratings yet

- Motivational Theory PDFDocument36 pagesMotivational Theory PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- 6.nov 13 - NLM PDFDocument16 pages6.nov 13 - NLM PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- Rueda Reading - Psychology - Teacherbeliefs - Accepted - Final PDFDocument37 pagesRueda Reading - Psychology - Teacherbeliefs - Accepted - Final PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- Rail Technical Guide FinalDocument13 pagesRail Technical Guide FinalRidwan Akbar Jak JhonNo ratings yet

- 24.oct .13 NLM PDFDocument16 pages24.oct .13 NLM PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- TECREC 100 001 ENERGY STANDARD VER 1 2 Final PDFDocument37 pagesTECREC 100 001 ENERGY STANDARD VER 1 2 Final PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- 17.oct .13 NLM PDFDocument16 pages17.oct .13 NLM PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- SECTION 20710 Flash Butt Rail Welding: Caltrain Standard SpecificationsDocument8 pagesSECTION 20710 Flash Butt Rail Welding: Caltrain Standard SpecificationsminchanmonNo ratings yet

- 1344249181201-Seniority of Inspectors PDFDocument10 pages1344249181201-Seniority of Inspectors PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- Population Density, 2000: Gridded Population of The WorldDocument1 pagePopulation Density, 2000: Gridded Population of The WorldminchanmonNo ratings yet

- ORRTUmins310309 PDFDocument11 pagesORRTUmins310309 PDFminchanmonNo ratings yet

- Ce4017 09Document31 pagesCe4017 09minchanmonNo ratings yet

- Chapter 57Document26 pagesChapter 57minchanmonNo ratings yet