Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Vda de Canilang Vs Court of Appeals

Vda de Canilang Vs Court of Appeals

Uploaded by

Man2x SalomonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Vda de Canilang Vs Court of Appeals

Vda de Canilang Vs Court of Appeals

Uploaded by

Man2x SalomonCopyright:

Available Formats

Digested by: Grace Jayne Dingal Subject: Insurance Law Title: Vda. DE CANILANG v.

COURT OF Topic: Test of materiality in concealment Facts: On 18 June 1982, Jaime Canilang consulted Dr. Claudio and was diagnosed as suffering from "sinus tachycardia And was latter found to have "acute bronchitis." On next day, Jaime applied for a "non-medical" insurance policy with respondent Great Pacific Life Assurance naming his wife, Thelma Canilang, as his beneficiary. Jaime was issued ordinary life insurance Policy effective as of 9 August 1982. On 5 August 1983, Jaime Canilang died of "congestive heart failure," "anemia," and "chronic anemia." Petitioner, widow and beneficiary of the insured, filed a claim with Great Pacific which the insurer denied upon the ground that the insured had concealed material information from it. Petitioner filed a complaint against Great Pacific with the Insurance Commission for recovery of the insurance proceeds. During the hearing called by the Insurance Commissioner, petitioner testified that she was not aware of any serious illness suffered by her late husband. The medical declaration which was set out in the application for insurance executed by Jaime Canilang read as follows: xxxx (1) I have not been confined in any hospital, sanitarium or infirmary, nor receive any medical or surgical advice/attention within the last five (5) years. (2) I have never been treated nor consulted a physician for a heart condition, high blood pressure, cancer, diabetes, lung, kidney, stomach disorder, or any other physical impairment. (3) I am, to the best of my knowledge, in good health. EXCEPTIONS: xxx Issue: Whether or not there is a material concealment Held: There is a material concealment. On appeal by Great Pacific, the Court of Appeals reversed and set aside the decision of the Insurance Commissioner and dismissed Thelma Canilang's complaint and Great Pacific's counterclaim. The Court of Appeals found that the failure of Jaime Canilang to disclose previous medical consultation and treatment constituted material information which should have been communicated to Great Pacific to enable the latter to make proper inquiries. Canilang failed to disclose, under the caption "Exceptions," that he had twice consulted Dr. Claudio who had found him to be suffering from "sinus tachycardia" and "acute bronchitis." The provisions of P.D. No. 1460, also known as the Insurance Code of 1978 read as follows: Sec. 26. A neglect to communicate that which a party knows and ought to communicate, is called a concealment. xxx xxx xxx Sec. 28. Each party to a contract of insurance must communicate to the other, in good faith, all factors within his knowledge which are material to the contract and as to which he makes no warranty, and which the other has not the means of ascertaining.

The information concealed must be information which the concealing party knew and "ought to [have] communicate[d]," that is to say, information which was "material to the contract." The test of materiality is contained in Section 31 of the Insurance Code of 1978 which reads: Sec. 31. Materially is to be determined not by the event, but solely by the probable and reasonable influence of the facts upon the party to whom the communication is due, in forming his estimate of the disadvantages of the proposed contract, or in making his inquiries. The information which Jaime Canilang failed to disclose was material to the ability of Great Pacific to estimate the probable risk he presented as a subject of life insurance. Had Canilang disclosed his visits to his doctor in the insurance application, it may be reasonably assumed that Great Pacific would have made further inquiries and would have probably refused to issue a non-medical insurance policy or, at the very least, required a higher premium for the same coverage. The materiality of the information withheld by Great Pacific did not depend upon the state of mind of Jaime Canilang. A man's state of mind or subjective belief is not capable of proof in our judicial process, except through proof of external acts or failure to act from which inferences as to his subjective belief may be reasonably drawn. Neither does materiality depend upon the actual or physical events which ensue. Materiality relates rather to the "probable and reasonable influence of the facts" upon the party to whom the communication should have been made, in assessing the risk involved in making or omitting to make further inquiries and in accepting the application for insurance; that "probable and reasonable influence of the facts" concealed must, of course, be determined objectively, by the judge ultimately. The insurance Great Pacific applied for was a "non-medical" insurance policy. In Saturnino v. Philippine-American Life Insurance Company, this Court held that: .. . if anything, the waiver of medical examination [in a non-medical insurance contract] renders even more material the information required of the applicant concerning previous condition of health and diseases suffered, for such information necessarily constitutes an important factor which the insurer takes into consideration in deciding whether to issue the policy or not . . . The Insurance Code of 1978 was amended by B.P. Blg. 874. This subsequent statute modified Section 27 of the Insurance Code of 1978 so as to read as follows: Sec. 27. A concealment whether intentional or unintentional entitles the injured party to rescind a contract of insurance. The Commissioner is wrong when it said that by deleting the phrase "intentional or unintentional," the Insurance Code of 1978 (prior to its amendment by B.P. Blg. 874) intended to limit the kinds of concealment which generate a right to rescind on the part of the injured party to "intentional concealments." "Intentional" and "unintentional" cancel each other out. The deletion of the phrase "whether intentional or unintentional" could not have had the effect of imposing an affirmative requirement that a concealment must be intentional if it is to entitle the injured party to rescind a contract of insurance. The restoration in 1985 by B.P. Blg. 874 of the phrase "whether intentional or unintentional" merely underscored the fact that all throughout (from 1914 to 1985), the statute did not require proof that concealment must be "intentional" in order to authorize rescission by the injured party. The nature of the facts not conveyed to the insurer was such that the failure to communicate must have been intentional rather than merely inadvertent. For Jaime Canilang could not have been unaware that his heart beat would at times rise to high and

alarming levels and that he had consulted a doctor twice in the 2 months before applying for non-medical insurance. The last medical consultation took place just the day before the insurance application was filed. Jaime Canilang went to visit his doctor precisely because of the discomfort and concern brought about by his experiencing "sinus tachycardia." We find it difficult to take seriously the argument that Great Pacific had waived inquiry into the concealment by issuing the insurance policy notwithstanding Canilang's failure to set out answers to some of the questions in the insurance application. Such failure precisely constituted concealment on the part of Canilang. Petitioner's argument, if accepted, would obviously erase Section 27 from the Insurance Code of 1978. It remains only to note that the Court of Appeals finding that the parties had not agreed in the pretrial before the Insurance Commission that the relevant issue was whether or not Jaime Canilang had intentionally concealed material information from the insurer, was supported by the evidence of record, i.e., the Pre-trial Order itself dated 17 October 1984 and the Minutes of the Pre-trial Conference dated 15 October 1984, which "readily shows that the word "intentional" does not appear in the statement or definition of the issue in the said Order and Minutes." WHEREFORE, the Petition for Review is DENIED for lack of merit and the Decision of the Court of is AFFIRMED.

You might also like

- Sps. Cha v. CA (Digest)Document1 pageSps. Cha v. CA (Digest)Tini GuanioNo ratings yet

- INSURANCE - Spouses Tibay vs. Court of AppealsDocument3 pagesINSURANCE - Spouses Tibay vs. Court of AppealsJakeDanduan100% (2)

- FILIPINAS COMPAÑÍA A DE SEGUROS Vs .TAN CHAUCODocument3 pagesFILIPINAS COMPAÑÍA A DE SEGUROS Vs .TAN CHAUCORenz Aimeriza AlonzoNo ratings yet

- INSURANCE Philamlife Vs Auditor GeneralDocument2 pagesINSURANCE Philamlife Vs Auditor Generalmichelle zatarain100% (1)

- JUAN v. JUANDocument1 pageJUAN v. JUANMan2x Salomon100% (1)

- Lesson 1 - Short Vowel 'A'Document5 pagesLesson 1 - Short Vowel 'A'Man2x Salomon100% (1)

- Bier v. Bier Case DigestDocument2 pagesBier v. Bier Case DigestMan2x Salomon0% (1)

- 7 Fil Estate Properties Inc. v. Homena ValenciaDocument4 pages7 Fil Estate Properties Inc. v. Homena Valenciasahara lockwoodNo ratings yet

- Argente v. West Coast Life InsuranceDocument2 pagesArgente v. West Coast Life InsuranceMan2x Salomon100% (1)

- Thelma Vda. de Canilang v. CADocument1 pageThelma Vda. de Canilang v. CAlealdeosaNo ratings yet

- Philamcare Health Systems V CADocument3 pagesPhilamcare Health Systems V CAsmtm06100% (1)

- 067 Sunlife V BacaniDocument1 page067 Sunlife V BacaniD De Leon100% (1)

- NG Gan Zee v. Asian Crusader LifeDocument2 pagesNG Gan Zee v. Asian Crusader LifeIldefonso HernaezNo ratings yet

- Florendo v. Philam PlansDocument1 pageFlorendo v. Philam PlansJohney Doe50% (2)

- Malayan Insurance vs. Pap Co. LTDDocument2 pagesMalayan Insurance vs. Pap Co. LTDKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- Cathay Insurance Co Vs CADocument1 pageCathay Insurance Co Vs CAZoe VelascoNo ratings yet

- Qua Chee Gan v. Law UnionDocument2 pagesQua Chee Gan v. Law UnionBion Henrik PrioloNo ratings yet

- UCPB General Insurance V Masagana TelemartDocument3 pagesUCPB General Insurance V Masagana TelemartArtemisTzy100% (1)

- Saturnino vs. Phil American LifeDocument2 pagesSaturnino vs. Phil American LifeKelsey Olivar MendozaNo ratings yet

- 06 Blue Cross Health Care, Inc. v. OlivaresDocument3 pages06 Blue Cross Health Care, Inc. v. OlivaresRem SerranoNo ratings yet

- Saturnino Vs PhilamlifeDocument1 pageSaturnino Vs PhilamlifeAnnabelle BustamanteNo ratings yet

- Malayan Insurance Co., Inc. vs. Cruz Arnaldo DigestDocument3 pagesMalayan Insurance Co., Inc. vs. Cruz Arnaldo DigestMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- Development Insurance Corp V.S. IACDocument2 pagesDevelopment Insurance Corp V.S. IACMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- HEIRS OF LORETO MARAMAG Vs EVA VERNA MARAMAGDocument2 pagesHEIRS OF LORETO MARAMAG Vs EVA VERNA MARAMAGPaulo Villarin100% (1)

- Makati Tuscany Condominium Corporation Vs Court of AppealsDocument1 pageMakati Tuscany Condominium Corporation Vs Court of AppealssappNo ratings yet

- Enriquez V Sunlife Assurance DigestDocument1 pageEnriquez V Sunlife Assurance DigestJLNo ratings yet

- American Home Assurance V ChuaDocument1 pageAmerican Home Assurance V ChuaRoxanne AvilaNo ratings yet

- Sunlife Canada v. CA Case DigestDocument2 pagesSunlife Canada v. CA Case DigestYodh Jamin Ong100% (1)

- Insurance Geogonia Vs CADocument2 pagesInsurance Geogonia Vs CAmichelle zatarainNo ratings yet

- White Gold Marine Services, Inc Vs Pioneer Insurance and Surety Corporation and The Steamship Mutual Underwriting Association (Bermuda) LTD DigestDocument2 pagesWhite Gold Marine Services, Inc Vs Pioneer Insurance and Surety Corporation and The Steamship Mutual Underwriting Association (Bermuda) LTD DigestAbilene Joy Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- TIBAY Vs CA Digest - MungcalDocument2 pagesTIBAY Vs CA Digest - Mungcalc2_charishmungcalNo ratings yet

- MANILA BANKERS v. ABAN - GR No. 175666Document4 pagesMANILA BANKERS v. ABAN - GR No. 175666Christopher Jan DotimasNo ratings yet

- La Razon Social Vs Union InsuranceDocument2 pagesLa Razon Social Vs Union InsurancePam RamosNo ratings yet

- Insurance: Verendia V. Ca G.R. No. 75605 January 22, 1993Document2 pagesInsurance: Verendia V. Ca G.R. No. 75605 January 22, 1993LaraNo ratings yet

- Philippine Phoenix Surety Vs WoodworkDocument4 pagesPhilippine Phoenix Surety Vs WoodworkSamael MorningstarNo ratings yet

- 016 Manila Mahogany V CADocument1 page016 Manila Mahogany V CAmendozaimeeNo ratings yet

- Digest of Fortune Insurance and Surety Co. v. CA (G.R. No. 115278)Document2 pagesDigest of Fortune Insurance and Surety Co. v. CA (G.R. No. 115278)Rafael Pangilinan100% (1)

- Young vs. Midland Textile Insurance CompanyDocument2 pagesYoung vs. Midland Textile Insurance CompanyMan2x Salomon100% (2)

- Manila Bankers Life Insurance Corp Vs AbanDocument3 pagesManila Bankers Life Insurance Corp Vs Abanana ortiz100% (1)

- Insular V Ebrado DigestDocument2 pagesInsular V Ebrado DigestKath100% (2)

- RCBC Vs CADocument3 pagesRCBC Vs CAJuris MendozaNo ratings yet

- Pacific Timber Export Corporation vs. CADocument2 pagesPacific Timber Export Corporation vs. CAMarry LasherasNo ratings yet

- Great Pacific Life Assurance Corp. v. Court of AppealsDocument3 pagesGreat Pacific Life Assurance Corp. v. Court of AppealsLance LagmanNo ratings yet

- Manila Mahogany Manufacturing v. CA and Zenith Insurance Case DigestDocument2 pagesManila Mahogany Manufacturing v. CA and Zenith Insurance Case DigestYodh Jamin OngNo ratings yet

- Bachrach v. British Americaan Ass. Co Digested CaseDocument2 pagesBachrach v. British Americaan Ass. Co Digested CaseMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- Choa Tiek Seng v. CADocument2 pagesChoa Tiek Seng v. CASoc SaballaNo ratings yet

- Digest of Vda. de Gabriel v. CA (G.R. No. 103883)Document2 pagesDigest of Vda. de Gabriel v. CA (G.R. No. 103883)Rafael Pangilinan100% (3)

- Malayan Insurance Vs Philippine First InsuranceDocument1 pageMalayan Insurance Vs Philippine First Insurancejamkt0% (1)

- Digest of Edillon v. Manila Bankers Life Insurance Corp. (G.R. No. 34200)Document1 pageDigest of Edillon v. Manila Bankers Life Insurance Corp. (G.R. No. 34200)Rafael PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Insurance - de La Fuente vs. Fortune Life Insurance Co., Inc., G.R. No. 224863, December 2, 2020Document2 pagesInsurance - de La Fuente vs. Fortune Life Insurance Co., Inc., G.R. No. 224863, December 2, 2020rei0% (1)

- Mayer Steel Pipe Corporation Vs Court of AppealsDocument3 pagesMayer Steel Pipe Corporation Vs Court of AppealsIhon BaldadoNo ratings yet

- Pan Malayan vs. CA Digest (Insurance)Document2 pagesPan Malayan vs. CA Digest (Insurance)Elerlenne Lim100% (2)

- San Miguel Brewery Vs La Union 1361Document4 pagesSan Miguel Brewery Vs La Union 1361Angelic ArcherNo ratings yet

- Choa Tiek Seng Vs CADocument1 pageChoa Tiek Seng Vs CAEarl LarroderNo ratings yet

- South Sea Surety v. CADocument2 pagesSouth Sea Surety v. CAglecie_co12No ratings yet

- Loyola Life Plans, Inc. v. ATR Professional Life Assurance Corp.Document2 pagesLoyola Life Plans, Inc. v. ATR Professional Life Assurance Corp.lemonade3762No ratings yet

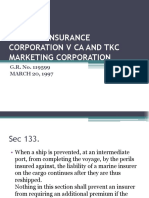

- Malayan Insurance Corporation V CA and TKC MarketingDocument7 pagesMalayan Insurance Corporation V CA and TKC MarketingKristine Garcia100% (2)

- Travellers Insurance vs. CADocument1 pageTravellers Insurance vs. CANiñanne Nicole Baring BalbuenaNo ratings yet

- Gulf Resorts Inc Vs Philippine Charter Insurance CorpDocument2 pagesGulf Resorts Inc Vs Philippine Charter Insurance CorpJ. LapidNo ratings yet

- Pacific Timber v. CADocument2 pagesPacific Timber v. CAkmand_lustregNo ratings yet

- CD - 11. Edillon vs. Manila Bankers Life InsuranceDocument2 pagesCD - 11. Edillon vs. Manila Bankers Life InsuranceAlyssa Alee Angeles JacintoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 92492 June 17, 1993 - Thelma Vda. de Canilang v. Court of Appeals, Et Al.Document11 pagesG.R. No. 92492 June 17, 1993 - Thelma Vda. de Canilang v. Court of Appeals, Et Al.Vanny Joyce BaluyutNo ratings yet

- Vda. de Canilang vs. CA 223 SCRA 443 June 17 1993Document8 pagesVda. de Canilang vs. CA 223 SCRA 443 June 17 1993wenny capplemanNo ratings yet

- Vda. de Canilang vs. Court of AppealsDocument7 pagesVda. de Canilang vs. Court of AppealsAriel AbisNo ratings yet

- TAPAYAN v. MartinezDocument1 pageTAPAYAN v. MartinezMan2x Salomon100% (1)

- Facts:: G.R. No. 214300, July 26, 2017 People of The Philippines, Petitioner vs. MANUEL ESCOBAR, RespondentDocument1 pageFacts:: G.R. No. 214300, July 26, 2017 People of The Philippines, Petitioner vs. MANUEL ESCOBAR, RespondentMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- Usares v. PeopleDocument1 pageUsares v. PeopleMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- Salvador v. ChuaDocument1 pageSalvador v. ChuaMan2x Salomon100% (2)

- Valderrama v. VigdenDocument1 pageValderrama v. VigdenMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 188794, September 02, 2015 Honesto Ogayon Y Diaz People of The Philippines FactsDocument1 pageG.R. No. 188794, September 02, 2015 Honesto Ogayon Y Diaz People of The Philippines FactsMan2x Salomon100% (1)

- The City of Bacolod v. Phuture Visions Co., IncDocument2 pagesThe City of Bacolod v. Phuture Visions Co., IncMan2x Salomon100% (3)

- Sanico v. PeopleDocument1 pageSanico v. PeopleMan2x Salomon100% (1)

- Personal Collection Direct Selling, Inc. v. CarandangDocument1 pagePersonal Collection Direct Selling, Inc. v. CarandangMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- HERNAN v. SandiganbayanDocument1 pageHERNAN v. SandiganbayanMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- People v. GimenezDocument1 pagePeople v. GimenezMan2x Salomon100% (1)

- Remedial Case DigestDocument2 pagesRemedial Case DigestMan2x Salomon100% (3)

- Bonsubre v. YerroDocument2 pagesBonsubre v. YerroMan2x Salomon100% (1)

- G.R. No. 224673, January 22, 2018 CECILIA RIVAC, Petitioner, v. People of The Philippines, Respondent. FactsDocument1 pageG.R. No. 224673, January 22, 2018 CECILIA RIVAC, Petitioner, v. People of The Philippines, Respondent. FactsMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 193150, January 23, 2017 LOIDA M. JAVIER, Petitioner, vs. PEPITO GONZALES, RespondentDocument2 pagesG.R. No. 193150, January 23, 2017 LOIDA M. JAVIER, Petitioner, vs. PEPITO GONZALES, RespondentMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- Rule 128: General Provisions G.R. No. 204289 November 22, 2017 FERNANDO MANCOL, JR., Petitioner vs. Development Bank of The Philippines, RespondentDocument1 pageRule 128: General Provisions G.R. No. 204289 November 22, 2017 FERNANDO MANCOL, JR., Petitioner vs. Development Bank of The Philippines, RespondentMan2x Salomon100% (2)

- Government Service Insurance System v. CADocument1 pageGovernment Service Insurance System v. CAMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- BARUT v. PeopleDocument1 pageBARUT v. PeopleMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- Rule 126: Search and Seizure G.R. No. 218891, September 19, 2016 Edmund Bulauitan Y Mauayan, PHILIPPINES, Respondent. FactsDocument1 pageRule 126: Search and Seizure G.R. No. 218891, September 19, 2016 Edmund Bulauitan Y Mauayan, PHILIPPINES, Respondent. FactsMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- Nimals Xe Rrow: ReviewDocument6 pagesNimals Xe Rrow: ReviewMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- ASTRID A. VAN DE BRUG, Petitioner, - versus-PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BANK, RespondentDocument3 pagesASTRID A. VAN DE BRUG, Petitioner, - versus-PHILIPPINE NATIONAL BANK, RespondentMan2x Salomon100% (1)

- Lesson 3 - 'CC'Document9 pagesLesson 3 - 'CC'Man2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- Ngo Te v. Yu-Te Case DigestDocument2 pagesNgo Te v. Yu-Te Case DigestMan2x Salomon100% (2)

- Trace PDFDocument1 pageTrace PDFMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- Alphabet GalleryDocument1 pageAlphabet GalleryMan2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- Lesson 4 - 'DD'Document5 pagesLesson 4 - 'DD'Man2x SalomonNo ratings yet

- Hiyas Savings v. Acuna Case DigestDocument2 pagesHiyas Savings v. Acuna Case DigestMan2x Salomon100% (1)

- CjusticeDocument353 pagesCjusticePuia RenthleiNo ratings yet

- 2 - Baliwag Transit V CADocument2 pages2 - Baliwag Transit V CALAW10101No ratings yet

- G.R. No. 161075.-Consing v. PPDocument11 pagesG.R. No. 161075.-Consing v. PPJohn Patrick IsraelNo ratings yet

- Ghosoph v. Kottmann, Ariz. Ct. App. (2015)Document6 pagesGhosoph v. Kottmann, Ariz. Ct. App. (2015)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Rule 04 - VenueDocument18 pagesRule 04 - VenueRalph Christian Lusanta Fuentes100% (1)

- 003 G.R. No. 226846Document6 pages003 G.R. No. 226846Paul ToguayNo ratings yet

- Mirjan DamaskaDocument6 pagesMirjan Damaskaestevam tavares de freitasNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 213394 - Spouses Pacquiao V PDFDocument21 pagesG.R. No. 213394 - Spouses Pacquiao V PDFindie100% (1)

- Miles City Bank v. AskinDocument2 pagesMiles City Bank v. AskinTippy Dos Santos50% (2)

- RCBC v. Hi-Tri Development Corporation, G.R. No. 192413, June 13, 2012Document12 pagesRCBC v. Hi-Tri Development Corporation, G.R. No. 192413, June 13, 2012liz kawiNo ratings yet

- Case Brief and Synthesis On ParricideDocument3 pagesCase Brief and Synthesis On Parricidemma100% (1)

- Pioneer Texturizing Corp Vs NLRCDocument1 pagePioneer Texturizing Corp Vs NLRCVin LacsieNo ratings yet

- What Is The Difference Between The Criminal and The Civil LawDocument4 pagesWhat Is The Difference Between The Criminal and The Civil LawChaya SeebaluckNo ratings yet

- Stat Con Chapter 2 CasesDocument263 pagesStat Con Chapter 2 CasesRichard BalaisNo ratings yet

- Viado Non v. Court of AppealsDocument5 pagesViado Non v. Court of AppealsQuennie Iris BulataoNo ratings yet

- Saleen, Inc. v. Wade - Document No. 5Document1 pageSaleen, Inc. v. Wade - Document No. 5Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Petition For Certiorari: Court of AppealsDocument7 pagesPetition For Certiorari: Court of AppealsDe Vera ChristianNo ratings yet

- POWERS AND DUTIES-week 2Document259 pagesPOWERS AND DUTIES-week 2Nievelita OdasanNo ratings yet

- Khosrow Minucher vs. Hon. Court of Appeals, Arthur W. Scalzo, JRDocument11 pagesKhosrow Minucher vs. Hon. Court of Appeals, Arthur W. Scalzo, JRjieun lee100% (1)

- Case Digest (Habeas Corpus) Spec ProDocument29 pagesCase Digest (Habeas Corpus) Spec ProLemuel Angelo M. Eleccion100% (4)

- Labrador v. CADocument5 pagesLabrador v. CAMyrahNo ratings yet

- Court Ruling On GM's 'Tasteless' Use of Shirtless Albert Einstein in AdDocument16 pagesCourt Ruling On GM's 'Tasteless' Use of Shirtless Albert Einstein in AdLos Angeles Daily NewsNo ratings yet

- Del Monte vs. CADocument3 pagesDel Monte vs. CABeverly Jane H. BulandayNo ratings yet

- Surya Dev Rai Vs Ram Chander RaiDocument15 pagesSurya Dev Rai Vs Ram Chander RaiShivam PatelNo ratings yet

- People V Seraspe GR 180919 Jan 9 2013Document2 pagesPeople V Seraspe GR 180919 Jan 9 2013Raymond Adrian Padilla ParanNo ratings yet

- 13 - Marvel Building Corporation Et Al Vs David Case DigestDocument2 pages13 - Marvel Building Corporation Et Al Vs David Case DigestMarjorie Porcina100% (2)

- ABQ 119 To 125Document42 pagesABQ 119 To 125Alimozaman DiamlaNo ratings yet

- United States v. Watson, 4th Cir. (1996)Document14 pagesUnited States v. Watson, 4th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Legal Method 1st DraftDocument16 pagesLegal Method 1st DraftHardik BishnoiNo ratings yet