Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Portfolio Assessment in A Competence-Based English As A Foreign Language (Efl) Instruction

Portfolio Assessment in A Competence-Based English As A Foreign Language (Efl) Instruction

Uploaded by

Muhamad TaufikCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Samples of Portfolio ProposalDocument43 pagesSamples of Portfolio Proposalwahanaajaran0% (1)

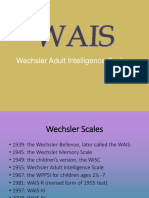

- Wechsler Adult Intelligence ScalesDocument20 pagesWechsler Adult Intelligence ScalesUkhtSameehNo ratings yet

- 2013-Applyin AR To EslDocument21 pages2013-Applyin AR To EslFathima RawshanNo ratings yet

- 4677 9292 1 SMDocument9 pages4677 9292 1 SMHuda GNo ratings yet

- Performance and Portfolio Assessment ForDocument38 pagesPerformance and Portfolio Assessment ForAhmatSudarmajiNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Performance in EFL Teaching Practicum: Student Teachers' ViewsDocument14 pagesAssessing The Performance in EFL Teaching Practicum: Student Teachers' ViewsSaira NazNo ratings yet

- CurriculumDocument10 pagesCurriculumJorge ServinNo ratings yet

- Learning Strategies Used by The Students in Performance Assessment in EFL ClassroomDocument14 pagesLearning Strategies Used by The Students in Performance Assessment in EFL ClassroomKhor Huey KeeNo ratings yet

- Portopolio - MiskiahDocument8 pagesPortopolio - MiskiahM MirzaNo ratings yet

- Assessment For Learning and EAL LearnersDocument7 pagesAssessment For Learning and EAL LearnersSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- 6.si4sellan Final Formatted ProofedDocument24 pages6.si4sellan Final Formatted ProofedLaser RomiosNo ratings yet

- 677 1478 1 SMDocument15 pages677 1478 1 SMNatalia FaleroNo ratings yet

- Authentic Assessment Through Porto FolioDocument23 pagesAuthentic Assessment Through Porto FolioEridafithri EridafithriNo ratings yet

- M-4287 (Assessment Report)Document5 pagesM-4287 (Assessment Report)Su TiendaNo ratings yet

- EJ1283061Document18 pagesEJ1283061isna muhammadfathoniNo ratings yet

- 2723-Article Text-5360-1-10-20150129Document19 pages2723-Article Text-5360-1-10-20150129Erda BakarNo ratings yet

- English Teachers Classroom Assessment Practices: International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE)Document11 pagesEnglish Teachers Classroom Assessment Practices: International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE)Daisymae MallapreNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5 Portfolio AssessmentDocument9 pagesLesson 5 Portfolio AssessmentMayraniel RuizolNo ratings yet

- A Study On Turkish EFL Teachers Beliefs About Assessment and Its Different Uses in Teaching English (#528046) - 650694Document12 pagesA Study On Turkish EFL Teachers Beliefs About Assessment and Its Different Uses in Teaching English (#528046) - 65069420040279 Nguyễn Thị Hoàng DiệpNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Formative Assessment in The Textbook For Senior High School Grade XIDocument4 pagesEvaluation of Formative Assessment in The Textbook For Senior High School Grade XIFeby RahmiNo ratings yet

- The Role of Portfolio Assessment and Reflection On Process WritingDocument33 pagesThe Role of Portfolio Assessment and Reflection On Process WritingJohn Luis Masangkay BantolinoNo ratings yet

- KC6 67Document13 pagesKC6 67Asala hameedNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Feedback Practices in The PDFDocument10 pagesAssessment and Feedback Practices in The PDFNessma baraNo ratings yet

- The Use of Portfolio in English Language TeachingDocument7 pagesThe Use of Portfolio in English Language TeachingNana PriajanaNo ratings yet

- Teacher LearningDocument71 pagesTeacher Learningespanol.a.tu.ritmoNo ratings yet

- AssessmentPortfolios PDFDocument2 pagesAssessmentPortfolios PDFDaniel de AbreuNo ratings yet

- Chapter VDocument8 pagesChapter VKadal KrianNo ratings yet

- Illustrating Formative Assessment in TBLTDocument10 pagesIllustrating Formative Assessment in TBLTAudyNo ratings yet

- 6928 13793 1 SMDocument9 pages6928 13793 1 SMmadeNo ratings yet

- Innovation in AssessmentDocument30 pagesInnovation in AssessmentWejang AlvinNo ratings yet

- Reflections of ELT Students On Their Progress in LDocument11 pagesReflections of ELT Students On Their Progress in Laya osamaNo ratings yet

- EFL Teachers' Student-Centered Pedagogy and Assessment Practices: Challenges and SolutionsDocument11 pagesEFL Teachers' Student-Centered Pedagogy and Assessment Practices: Challenges and SolutionsJournal of Education and LearningNo ratings yet

- Assessment in the EFL University Classroom: between Tradition and Innovation:يعمالجا ىوتسلما ةيبنجلاا ةيزيلجـنلاا ةغللا مسق في مييقتلا ةثيدلحا و ةيديلقتلا قرطلا ينبDocument8 pagesAssessment in the EFL University Classroom: between Tradition and Innovation:يعمالجا ىوتسلما ةيبنجلاا ةيزيلجـنلاا ةغللا مسق في مييقتلا ةثيدلحا و ةيديلقتلا قرطلا ينبMajid MadhiNo ratings yet

- Lecture 01 Introduction To Assessment and Related ConceptsDocument6 pagesLecture 01 Introduction To Assessment and Related ConceptsthusneldachanNo ratings yet

- Evaluating An English Language Teacher Education Program Through Peacock's ModelDocument19 pagesEvaluating An English Language Teacher Education Program Through Peacock's ModelPinkyFarooqiBarfiNo ratings yet

- The Assessment and Evaluation in Teaching EnglishDocument8 pagesThe Assessment and Evaluation in Teaching EnglishSririzkii WahyuniNo ratings yet

- Laporan CJR VanessaninDocument8 pagesLaporan CJR VanessaninVanessa NasutionNo ratings yet

- BC 83Document9 pagesBC 83Asala hameedNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Assessment PDFDocument10 pagesPortfolio Assessment PDFShu Xian LuoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-3Document14 pagesChapter 1-3Thoriq NajaNo ratings yet

- English Education at University Level: Who Is at The Centre of The Learning Process?Document14 pagesEnglish Education at University Level: Who Is at The Centre of The Learning Process?gab_tampuNo ratings yet

- Prof Ed 6 - LP4Document23 pagesProf Ed 6 - LP4Marisol OtidaNo ratings yet

- Journal GEEJ: P-ISSN 2355-004X E-ISSN 2502-6801Document13 pagesJournal GEEJ: P-ISSN 2355-004X E-ISSN 2502-6801lauraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document8 pagesChapter 4Vince OjedaNo ratings yet

- RJMV WC E1 GVDocument28 pagesRJMV WC E1 GVcatherinewai02No ratings yet

- 06 TsagariDocument27 pages06 Tsagariraluca_damian_6100% (1)

- Assessment Strategies in Language ClassroomDocument6 pagesAssessment Strategies in Language Classroomsegunbadmus834No ratings yet

- Portfolio AssessmentDocument33 pagesPortfolio AssessmentImam Dhyazlalu Cyankz100% (1)

- Portfolio AssessmentDocument7 pagesPortfolio Assessment217140231447No ratings yet

- The Bumpy Road of Assessment For Learning During Pandemic of COVID-19Document8 pagesThe Bumpy Road of Assessment For Learning During Pandemic of COVID-19Journal of Education and LearningNo ratings yet

- Language Assessment Principles - WashbackDocument8 pagesLanguage Assessment Principles - WashbackRosmalia Kasan100% (1)

- Chen, Rogers, Hu 2004 EFL Instructors Assessment PracticesDocument30 pagesChen, Rogers, Hu 2004 EFL Instructors Assessment PracticesOriana GSNo ratings yet

- Bab 2 by EnglishDocument18 pagesBab 2 by EnglishM.Nawwaf Al-HafidzNo ratings yet

- Designing A Classroom Language Test For Junior High School StudentsDocument12 pagesDesigning A Classroom Language Test For Junior High School StudentsDhelzHahihuhehoKjmNo ratings yet

- Article 1Document22 pagesArticle 1Janneth YanzaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Strategies Related To Students' CharacteristicsDocument8 pagesTeaching Strategies Related To Students' CharacteristicsPikir Wisnu WijayantoNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research Study: Teachers Experiences On Classroom ObservationDocument25 pagesQualitative Research Study: Teachers Experiences On Classroom ObservationLeah Carla LebrillaNo ratings yet

- Designing Portfolio Assessment of Speaking Skill For Vocational High School Students Firman WicaksonoDocument14 pagesDesigning Portfolio Assessment of Speaking Skill For Vocational High School Students Firman WicaksonoTaemin KimNo ratings yet

- 38 - The Interface Between Interlanguage, Pragmatics and Assessment - Proceedings of The 3rd Annual JALT Pan-SIG Conference.Document12 pages38 - The Interface Between Interlanguage, Pragmatics and Assessment - Proceedings of The 3rd Annual JALT Pan-SIG Conference.anhppNo ratings yet

- By Judy Kemp & Debby Toperoff: Guidelines For Portfolio AssessmentDocument27 pagesBy Judy Kemp & Debby Toperoff: Guidelines For Portfolio AssessmentJoshua LagonoyNo ratings yet

- The Influence of The Human Biorhythm in The Performance Sport ActivityDocument13 pagesThe Influence of The Human Biorhythm in The Performance Sport ActivityLarisa- Elena NegoescuNo ratings yet

- Lit CritDocument25 pagesLit CritJonna Mae Jalwin FullanteNo ratings yet

- Lab ReportDocument11 pagesLab ReportAnika O'ConnellNo ratings yet

- Case Study Prac RevisedDocument13 pagesCase Study Prac Revised20172428 YASHICA GEHLOT100% (1)

- Sip 2019-2022Document4 pagesSip 2019-2022jein_am97% (29)

- (2011) John Freedom: Energypsychology, The Future of Therapy?Document11 pages(2011) John Freedom: Energypsychology, The Future of Therapy?James Nicholls100% (1)

- Dual Relationships Between TherapistDocument18 pagesDual Relationships Between TherapistVictor Hugo EsquivelNo ratings yet

- Emerging Trends in Criminal LawDocument1 pageEmerging Trends in Criminal Lawapi-3742748No ratings yet

- What Smart Students Need Know PDFDocument14 pagesWhat Smart Students Need Know PDF007phantomNo ratings yet

- Risk Short IntroductionDocument3 pagesRisk Short IntroductionOanaMaria92No ratings yet

- Model Plan Lectie Cls.a VIII-aDocument4 pagesModel Plan Lectie Cls.a VIII-agerronimo100% (1)

- Group DynamicsDocument28 pagesGroup Dynamicskavitachordiya86100% (1)

- 9 Sports An IntroductionDocument14 pages9 Sports An IntroductionMelanie perez cortezNo ratings yet

- Organization As A Politics by Gareth MorganDocument37 pagesOrganization As A Politics by Gareth MorganJeliteng Pribadi67% (3)

- Rigor Rubric All SubjectsDocument6 pagesRigor Rubric All Subjectsapi-293015639No ratings yet

- Maryline Pimentel Professional Goals 2014-2015Document3 pagesMaryline Pimentel Professional Goals 2014-2015api-250421371No ratings yet

- Photoshop LessonDocument3 pagesPhotoshop Lessonapi-299330082No ratings yet

- Written Report - Group V - Control of AntecedentsDocument39 pagesWritten Report - Group V - Control of AntecedentsMJ FangoNo ratings yet

- Meet The Real Narcissists - Psychology TodayDocument13 pagesMeet The Real Narcissists - Psychology TodayDenisa TatuNo ratings yet

- Hiding Toys in SandDocument7 pagesHiding Toys in Sandapi-311000623No ratings yet

- Lesson Guide in Science 7 I. Objectives: Iiia-1)Document2 pagesLesson Guide in Science 7 I. Objectives: Iiia-1)Jespher GarciaNo ratings yet

- Mood Classification of Hindi Songs Based On Lyrics: December 2015Document8 pagesMood Classification of Hindi Songs Based On Lyrics: December 2015Vijay SakharaniNo ratings yet

- Stephen Krashen Second Language AcquisitionDocument4 pagesStephen Krashen Second Language AcquisitionTriya MutiaNo ratings yet

- 3rd Quarter Week 5 Day 2Document4 pages3rd Quarter Week 5 Day 2Joyce BrionesNo ratings yet

- Mukbadhir Vidhyarthiyon Ki Buddhi Eanv Samayojan Ka AdhyayanDocument12 pagesMukbadhir Vidhyarthiyon Ki Buddhi Eanv Samayojan Ka AdhyayanAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- AMB120 Bridging Cultures and AMB390 Bridging Cultures International Assessment Item 2: Report 30%Document2 pagesAMB120 Bridging Cultures and AMB390 Bridging Cultures International Assessment Item 2: Report 30%SamurdhiNo ratings yet

- IncestDocument6 pagesIncestJanenaRafalesPajulasNo ratings yet

- Teachers & Carers Guide PDFDocument11 pagesTeachers & Carers Guide PDFRosemarie FritschNo ratings yet

- Chapter IIIDocument3 pagesChapter IIIRenan S. GuerreroNo ratings yet

Portfolio Assessment in A Competence-Based English As A Foreign Language (Efl) Instruction

Portfolio Assessment in A Competence-Based English As A Foreign Language (Efl) Instruction

Uploaded by

Muhamad TaufikOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Portfolio Assessment in A Competence-Based English As A Foreign Language (Efl) Instruction

Portfolio Assessment in A Competence-Based English As A Foreign Language (Efl) Instruction

Uploaded by

Muhamad TaufikCopyright:

Available Formats

ISSN 0215-8250 PORTFOLIO ASSESSMENT IN A COMPETENCE-BASED ENGLISH AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE (EFL) INSTRUCTION By Anak Agung Istri Ngurah Marhaeni

English Department, Faculty of Language and Arts Education IKIP Negeri Singaraja ABSTRACT

51

This paper discusses some concepts dealing with one of the competencebased curriculum components namely classroom-based assessment. The review which is tailored to the context of English as a foreign language (EFL) instruction includes classroom-based assessment, portfolio assessment in EFL instruction, and potential problems in its implementation. Key words: competence-based curriculum, classroom-based assessment, portfolio assessment, EFL instruction ABSTRAK Tulisan ini mengkaji beberapa konsep yang berkaitan dengan salah satu komponen kurikulum berbasis kompetensi, yaitu asesmen berbasis kelas. Pembahasan yang dibatasi kepada asesmen dalam konteks pembelajaran bahasa Inggris sebagai bahasa asing (EFL) ini meliputi uraian tentang asesmen berbasis kelas, asesmen portofolio dalam pembelajaran EFL, dan kendala-kendala potensial yang dapat muncul dalam implementasinya. Kata kunci: kurikulum berbasis kompetensi, asesmen berbasis kelas, asesmen portofolio, pembelajaran EFL.

1. Introduction The Center of Curriculum (2002) has published a document which outlines the widely-used Competence-based Curriculum (Kurikulum Berbasis Kompetensi) that contains four related components, namely (1) management of competencebased curriculum, (2) curriculum and learning outcome, (3) classroom-based

__ Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pengajaran IKIP Negeri Khusus TH. XXXVI Desember 2003 Singaraja, Edisi

ISSN 0215-8250

52

assessment, and (4) teaching-learning activities. In light of the assessment orientation of the curriculum, it is apparent that there is a new view regarding assessment practice in the classroom. Worldwide, especially in countries where assessment in education gains so much attention, classroom-based assessment has been practiced for over two decades, in response to current orientation on how learning outcomes must be assessed. The implementation in schools grows rapidly because teachers and educators are not satisfied with the traditional practice of assessment that lacks of attention on individual students progress in learning; while there is an overreliance to the use of standardized tests, mostly in multiple choice type. Such tests are considered unable to capture the whole growth of students learning. Among the procedures of classroom-based assessment mentioned in the document, portfolio assessment has gained teachers attention. Despite the curriculum mandate and a growing interest in portfolio assessment, its use in assessing students growth brings about some concerns especially in the teaching of English as a foreign language (EFL) in Indonesia. So far, few references and guidelines are on reach. The purpose of this paper is to discuss about classroom-based assessment, portfolio assessment in EFL instruction, and potential obstacles in its implementation. 2. Classroom-Based Assessment The framework of assessment may be considered in terms of two broad categories: informal and formal (Cooper, 2000). Informal assessment utilizes nonstandardized procedures; formal assessment utilizes standardized procedures or procedures carried out under controlled conditions. Examples of informal assessment include the use of checklists, observations, and performance assessments. Informal assessments are clearly and easily made a part of instruction. Formal assessments include such tests like state tests, standardized achievement tests, and tests accompanying a published program. The standardized achievement tests are most useful in evaluating overall program growth as opposed to evaluating individual students progress or determining instructional

__ Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pengajaran IKIP Negeri Khusus TH. XXXVI Desember 2003

Singaraja, Edisi

ISSN 0215-8250

53

needs. The formal tests are not directly embedded to instruction, but they must reflect the instruction to be of value in students achievement. In the context of classroom where assessment is formative in nature, the use of standardized tests have been widely criticized for a number of reasons. DeFina (1992) summarizes the characteristics of informal assessment as they are compared with those of formal assessment, to make it clear that formal assessment is not relevant for classroom practice. NO. INFORMAL ASSESSMENT 1. In natural situation 2. Direct, hands-on information 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. FORMAL ASSESSMENT Testing atmosphere, not natural Not provides diagnostic information Provides students with opportunities Shows students weaknesses in a to demonstrate strengths and particular area weaknesses On-going, therefore gives a chance Assessment only once, and only for multiple assessment in a particular area Realistic, meaningful assessment Artificial, not realistic Opportunity for self-evaluation and Expects only one correct response reflection Promotes student-teacher Conferences are not a part of conferences assessment Student-centered instruction Curriculum-centered instruction Provides information for interested Provides judgments about student agencies about student knowledge achievement and artifacts

Classroom-based assessment is a component of the competence-based curriculum. It is so called classroombased assessment because it is carried out along with the teaching-learning activities. In other words, assessment is integrated with instruction (Kurikulum Berbasis Kompetensi, 2002). Further, the document states that the results of the assessment can (1) give feedback to the student about their strengths and weaknesses, (2) monitor and diagnose student progress for remedial purposes, (3) give feedback to teachers to improve his/her instructional programs, (4) promote student competence at different pace, and (5) have public accountability for higher public participation. Seeing the characteristics of such assessment orientation, in the framework of assessment classroom-based

__ Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pengajaran IKIP Negeri Khusus TH. XXXVI Desember 2003 Singaraja, Edisi

ISSN 0215-8250

54

assessment may be categorized informal as it is mainly used to know students progress and to identify their problems for remedial purposes. The document further mentions some assessment procedures which include portfolio, product/artifact, project, performance, and paper and pen tests. Considered new as it is first introduced in the recent curriculum, portfolio is actually not new. Historically, portfolios were first used in arts, which meant collections of an artists works over time that reflected his or her growth in arts. Then, portfolios were introduced to arts education. Later, portfolios were used in language, math, and science education. In language education, portfolios have been largely used especially in literacy instruction. As it is used in assessment process, a portfolio becomes a collection of a students works that reflects his/her progress in learning a language. Paulson and Paulson (1996) further define that portfolio is a purposeful collection of a students works that exhibit the students effort, progress, and achievement in one or more areas. The collection must include the students participation in selecting contents, the criteria for selection, the criteria for judging merit, and evidence of the students self-reflection. Based on the above definition, a portfolio is a portfolio when it provides a complex and comprehensive view of student performance in context. It is a portfolio when the student is a participant in, rather than the object of, assessment (Paulson et al, 1996). Portfolio assessment may be considered most appropriate as it reflects the basic philosophy of classroom-based assessment, that assessment is integrated with instruction. Portfolio assessment provides comprehensive information about student learning and achievement as it involves assessment of both process and product, obtained from a variety of tests and non tests. The richness of information in a portfolio is derived from its three essential elements: samples of student work, student self-assessment, and clearly stated criteria (OMalley and Valdez Pierce, 1996). As assessment orientation has moved from standardized, formal testing to classroom-based assessment, the use of portfolio as a procedure of assessment in language instruction is increasing.

__ Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pengajaran IKIP Negeri Khusus TH. XXXVI Desember 2003

Singaraja, Edisi

ISSN 0215-8250

55

3. Portfolio Assessment in EFL Instruction As discussed earlier, the competence-based curriculum requires the use of classroom-based assessment in monitoring students growth in learning a language, especially in reading and writing. Portfolio assessment is one procedure of such assessment orientation. One important instructional context that has supported and extended the use of portfolios in EFL classroom has been provided by the whole language approach (OMalley and Valdez Pierce, 1996). Proponents of the whole language approach view language as a whole; so breaking it into parts no longer maintains the nature of language itself (Goodman, 1986). Based on the view, the teaching of language must be holistic and authentic, just like how it is used in real life. The whole language approach supports active construction of knowledge through the use of student prior knowledge and promoting social interaction. This philosophy of language and language instruction has led to the use of portfolio assessment. Following the whole language approach, traditional assessment procedures becomes incongruent with current EFL classroom practices. Moya and OMalley (1994) mention three reasons for using portfolio in the assessment of EFL student language development: the limitation of single measure assessment, the complexity of the construct to be assessed, and the need for adaptable assessment techniques in EFL classroom. The first reason is clearly related to the kinds of language assessment used and their effects on instruction. Whereas standardized tests serve a purpose in education, the overuse of such tests has misled their functions. Charges have been made to standardized tests that they (1) do not provide information on progress in learning, so little can be known about individual strengths and weaknesses, (2) may reduce teaching to preparing for the tests, (3) focus attention on lower level skills, (4) treat students as if thought processes are all similar and reasons for answers irrelevant, and (5) emphasize quantifiable outcomes rather than instructionally relevant formative feedback (Moya and OMalley, 1994). Additionally, standardized tests that only measure one thing at one time have ignored the multifaceted nature of language proficiency.

__ Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pengajaran IKIP Negeri Khusus TH. XXXVI Desember 2003

Singaraja, Edisi

ISSN 0215-8250

56

The second reason still relates to the multifaceted, complex nature of language. Evidence of the complexity of the construct can be traced through recent theoretical views of reading comprehension and writing. Under the influence of the holistic perspectives on EFL language instruction, reading comprehension is considered a product of student interpretation of a text, based on the transaction between the student learning potential and the texts meaning potential (Rosenblatt, 1988; Weaver 1994). The interpretation varies depending on purposes of reading, prior knowledge of the material, and strategies for reading. Throughout the transactional process, students actively focus on elements of interest, relate information, infer meanings, and reflect on the significance of information. Similarly, writing is a complex skill involving sub skills in inventing and organizing ideas, and use of appropriate language expressions. Therefore, student language ability cannot adequately be reflected by selecting single correct answers of multiple choice items. In other words, a varied approach to assessment including tests and non tests are needed to ascertain student language ability. Portfolio assessment can facilitate the needs as it involves assessment of process and product. Finally, adaptability of portfolio assessment procedures may be seen in two major aspects. First, problems of foreign students of English in linguistic, cultural, and educational backgrounds can be addressed as portfolio assessment is largely individualized. Second, higher level skills that cannot be covered through multiple choice items can be facilitated through portfolio assessment. 4. Potential Problems in the Use of Portfolio Assessment in EFL Classroom It has been contented previously that in effect of current implementation of the competence-based curriculum, portfolio assessment is an alternative that might be adopted. The escalation of its use in EFL classroom creates a caution as it is feared such that new assessment practice may bring problems than lucks. Considerations on the characteristics of EFL learners will help in anticipating problems that may occur in its implementation.

__ Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pengajaran IKIP Negeri Khusus TH. XXXVI Desember 2003

Singaraja, Edisi

ISSN 0215-8250

57

An experimental research currently carried out by the writer on the use of portfolio assessment in a writing course of EFL students of English provides some critical aspects concerning potential problems that may confront teachers. First, the students classroom behavior indicates that they are not ready to take risks of their learning. This lack of risk-taking makes them progress quite slowly with their portfolio. As we know, in portfolio assessment students are provided with ample opportunities to work individually. Although they have been facilitated with sample materials, handouts, at hand helps on grammar, and selfevaluation checklists, however, they do not make use of those until they are told to do so. While they might not yet familiar with the strategy, a strong indication tells that they are afraid to do something that looks deviating from the teachers model. The indication is inferred from the fact that they do not start till they are confirmed that they are allowed or not allowed to do that. It is rare that they try to do something first, then confirm it with the teacher. Risk-taking is a major aspect in portfolio assessment. The students need to develop a sense that what they do is for the sake of their improvement. Hence, it is their duty as well as responsibility of whatever they do. Second, expressing themselves as active learners who know what they need seems not yet a value to the students. This can be seen through their reluctance in doing self-evaluation and writing reflection. They think that having an essay about the topic under assignment is important (because it has a score!), but doing self-evaluation on the essay and making reflection on the process they undergo in writing are not important (because they have no score!). Thus, the students are still very much product-oriented. Self-assessment is the key to portfolios (OMalley and Valdez Pierce, 1996). Without self-evaluation a portfolio is not a portfolio. Through selfevaluation students can map their route and check their progress in learning. The performance criteria provided in the checklists help students focus on precisely what it is that their work must show. Portfolio assessment also requires students self-reflect on their strengths and weaknesses, which will help them plan further action for improvement. Most teachers ask students to write their reflection as evidence or proof. Yet, as the

__ Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pengajaran IKIP Negeri Khusus TH. XXXVI Desember 2003 Singaraja, Edisi

ISSN 0215-8250

58

students are not accustomed to writing their experience and feeling, they find writing self-reflection is a difficult job. Considering the above phenomena observed in a classroom with portfoliobased assessment, two potential causes might be in effect. First, systematic portfolio assessment procedure is quite new for them and they need time to be accustomed to the practice. Second, it is suspected that the students do not yet gain a state of independence in learning. The students past experience in school did not promote independence. While the goals of a certain level of education as outlined by the curriculum do not explicitly deal with it, it needs to be realized that the ultimate goal of all education, formal and informal, is independence. In the process of learning, independence here definitely means independence in learning. An independent learner must be self-directed, responsible for their own goals. 5. Conclusion Portfolio assessment may not be considered either with full expectation or extreme suspicion. Like other procedures of assessment, it must be welcome with care. Professionally, EFL teachers implementing portfolio assessment in their instruction need to develop understanding on the philosophy of such an assessment; so that the procedure is not misled. Teachers need to not only advocate portfolio use, but also know how to implement portfolio assessment systematically in their classrooms. Psychologically, the teachers must be prepared to work hard, especially in preparing students to work with portfolio assessment. To approach portfolio assessment with anything less than a total dedication to developing a quality alternative assessment procedure is to relegate this potentially powerful approach to the realms of other educational fads (Moya and OMalley, 1994). BIBLIOGRAPHY Cooper, J.D. (2000). Literacy, Helping Children Construct Meaning 4th Edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. De Fina, A.A. (1992). Portfolio Assessment, Getting Started. New York: Scholastic Professional Books.

__ Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pengajaran IKIP Negeri Khusus TH. XXXVI Desember 2003 Singaraja, Edisi

ISSN 0215-8250

59

Goodman, K. (1986) Whats Whole in Whole Language, New Hampshire: Heinemann. Kemp, J. & Toperoff, D. (1998). Guidelines for Portfolio Assessment in Teaching English. Available at kempj@netvision.net.il and mailto:debby01@attglobal.net. Moya, S.S. & OMalley, J.M. (1994). ;A Portfolio Model for ESL;. The Journal of Educational Issues of Language Minorities. Vol. 13 (Spring). 13-36. OMalley, J.M. & Valdez Pierce, L. (1996). Authentic Assessment for English Language Learners. New York: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. Paulson F.L. and Paulson P.R. (1996). Assessing Portfolios Using the Constructivist Paradigm in R. Fogarty (Ed.). Student Portfolios, A Collection of Articles. Victoria, Australia: Hawker Brownlow Education. Paulson, F.L., Paulson, P.R., & C.A. Meyer (1996). What makes a portfolio a portfolio? in R. Fogarty (Ed.). Student Portfolios, A Collection of Articles. Victoria, Australia: Hawker Brownlow Education. Popham, W.J. (1995). Classroom Assessment, What Teachers Need to Know . Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Pusat Kurikulum Balitbang Depdiknas. (2002). Kurikulum Berbasis Kompetensi. Jakarta Rosenblatt, L. (1988). The Reader, the Text, the Poem. New Jersey: Macmillan. Salvia, J. & Ysseldyke, J.E. (1996). Assessment. 6th Edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. Weaver, C. (1994). Reading Process and Practice, from Sociopsycholinguistics to Whole Language 2nd Edition. New Hampshire: Heinemann. Wyaatt III, R.L. & Looper, S. (1999). So You Have to Have A Portfolio, a Teachers Guide to Preparation and Presentation. California: Corwin Press Inc.

__ Jurnal Pendidikan dan Pengajaran IKIP Negeri Khusus TH. XXXVI Desember 2003

Singaraja, Edisi

You might also like

- Samples of Portfolio ProposalDocument43 pagesSamples of Portfolio Proposalwahanaajaran0% (1)

- Wechsler Adult Intelligence ScalesDocument20 pagesWechsler Adult Intelligence ScalesUkhtSameehNo ratings yet

- 2013-Applyin AR To EslDocument21 pages2013-Applyin AR To EslFathima RawshanNo ratings yet

- 4677 9292 1 SMDocument9 pages4677 9292 1 SMHuda GNo ratings yet

- Performance and Portfolio Assessment ForDocument38 pagesPerformance and Portfolio Assessment ForAhmatSudarmajiNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Performance in EFL Teaching Practicum: Student Teachers' ViewsDocument14 pagesAssessing The Performance in EFL Teaching Practicum: Student Teachers' ViewsSaira NazNo ratings yet

- CurriculumDocument10 pagesCurriculumJorge ServinNo ratings yet

- Learning Strategies Used by The Students in Performance Assessment in EFL ClassroomDocument14 pagesLearning Strategies Used by The Students in Performance Assessment in EFL ClassroomKhor Huey KeeNo ratings yet

- Portopolio - MiskiahDocument8 pagesPortopolio - MiskiahM MirzaNo ratings yet

- Assessment For Learning and EAL LearnersDocument7 pagesAssessment For Learning and EAL LearnersSwati RaiNo ratings yet

- 6.si4sellan Final Formatted ProofedDocument24 pages6.si4sellan Final Formatted ProofedLaser RomiosNo ratings yet

- 677 1478 1 SMDocument15 pages677 1478 1 SMNatalia FaleroNo ratings yet

- Authentic Assessment Through Porto FolioDocument23 pagesAuthentic Assessment Through Porto FolioEridafithri EridafithriNo ratings yet

- M-4287 (Assessment Report)Document5 pagesM-4287 (Assessment Report)Su TiendaNo ratings yet

- EJ1283061Document18 pagesEJ1283061isna muhammadfathoniNo ratings yet

- 2723-Article Text-5360-1-10-20150129Document19 pages2723-Article Text-5360-1-10-20150129Erda BakarNo ratings yet

- English Teachers Classroom Assessment Practices: International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE)Document11 pagesEnglish Teachers Classroom Assessment Practices: International Journal of Evaluation and Research in Education (IJERE)Daisymae MallapreNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5 Portfolio AssessmentDocument9 pagesLesson 5 Portfolio AssessmentMayraniel RuizolNo ratings yet

- A Study On Turkish EFL Teachers Beliefs About Assessment and Its Different Uses in Teaching English (#528046) - 650694Document12 pagesA Study On Turkish EFL Teachers Beliefs About Assessment and Its Different Uses in Teaching English (#528046) - 65069420040279 Nguyễn Thị Hoàng DiệpNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Formative Assessment in The Textbook For Senior High School Grade XIDocument4 pagesEvaluation of Formative Assessment in The Textbook For Senior High School Grade XIFeby RahmiNo ratings yet

- The Role of Portfolio Assessment and Reflection On Process WritingDocument33 pagesThe Role of Portfolio Assessment and Reflection On Process WritingJohn Luis Masangkay BantolinoNo ratings yet

- KC6 67Document13 pagesKC6 67Asala hameedNo ratings yet

- Assessment and Feedback Practices in The PDFDocument10 pagesAssessment and Feedback Practices in The PDFNessma baraNo ratings yet

- The Use of Portfolio in English Language TeachingDocument7 pagesThe Use of Portfolio in English Language TeachingNana PriajanaNo ratings yet

- Teacher LearningDocument71 pagesTeacher Learningespanol.a.tu.ritmoNo ratings yet

- AssessmentPortfolios PDFDocument2 pagesAssessmentPortfolios PDFDaniel de AbreuNo ratings yet

- Chapter VDocument8 pagesChapter VKadal KrianNo ratings yet

- Illustrating Formative Assessment in TBLTDocument10 pagesIllustrating Formative Assessment in TBLTAudyNo ratings yet

- 6928 13793 1 SMDocument9 pages6928 13793 1 SMmadeNo ratings yet

- Innovation in AssessmentDocument30 pagesInnovation in AssessmentWejang AlvinNo ratings yet

- Reflections of ELT Students On Their Progress in LDocument11 pagesReflections of ELT Students On Their Progress in Laya osamaNo ratings yet

- EFL Teachers' Student-Centered Pedagogy and Assessment Practices: Challenges and SolutionsDocument11 pagesEFL Teachers' Student-Centered Pedagogy and Assessment Practices: Challenges and SolutionsJournal of Education and LearningNo ratings yet

- Assessment in the EFL University Classroom: between Tradition and Innovation:يعمالجا ىوتسلما ةيبنجلاا ةيزيلجـنلاا ةغللا مسق في مييقتلا ةثيدلحا و ةيديلقتلا قرطلا ينبDocument8 pagesAssessment in the EFL University Classroom: between Tradition and Innovation:يعمالجا ىوتسلما ةيبنجلاا ةيزيلجـنلاا ةغللا مسق في مييقتلا ةثيدلحا و ةيديلقتلا قرطلا ينبMajid MadhiNo ratings yet

- Lecture 01 Introduction To Assessment and Related ConceptsDocument6 pagesLecture 01 Introduction To Assessment and Related ConceptsthusneldachanNo ratings yet

- Evaluating An English Language Teacher Education Program Through Peacock's ModelDocument19 pagesEvaluating An English Language Teacher Education Program Through Peacock's ModelPinkyFarooqiBarfiNo ratings yet

- The Assessment and Evaluation in Teaching EnglishDocument8 pagesThe Assessment and Evaluation in Teaching EnglishSririzkii WahyuniNo ratings yet

- Laporan CJR VanessaninDocument8 pagesLaporan CJR VanessaninVanessa NasutionNo ratings yet

- BC 83Document9 pagesBC 83Asala hameedNo ratings yet

- Portfolio Assessment PDFDocument10 pagesPortfolio Assessment PDFShu Xian LuoNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-3Document14 pagesChapter 1-3Thoriq NajaNo ratings yet

- English Education at University Level: Who Is at The Centre of The Learning Process?Document14 pagesEnglish Education at University Level: Who Is at The Centre of The Learning Process?gab_tampuNo ratings yet

- Prof Ed 6 - LP4Document23 pagesProf Ed 6 - LP4Marisol OtidaNo ratings yet

- Journal GEEJ: P-ISSN 2355-004X E-ISSN 2502-6801Document13 pagesJournal GEEJ: P-ISSN 2355-004X E-ISSN 2502-6801lauraNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4Document8 pagesChapter 4Vince OjedaNo ratings yet

- RJMV WC E1 GVDocument28 pagesRJMV WC E1 GVcatherinewai02No ratings yet

- 06 TsagariDocument27 pages06 Tsagariraluca_damian_6100% (1)

- Assessment Strategies in Language ClassroomDocument6 pagesAssessment Strategies in Language Classroomsegunbadmus834No ratings yet

- Portfolio AssessmentDocument33 pagesPortfolio AssessmentImam Dhyazlalu Cyankz100% (1)

- Portfolio AssessmentDocument7 pagesPortfolio Assessment217140231447No ratings yet

- The Bumpy Road of Assessment For Learning During Pandemic of COVID-19Document8 pagesThe Bumpy Road of Assessment For Learning During Pandemic of COVID-19Journal of Education and LearningNo ratings yet

- Language Assessment Principles - WashbackDocument8 pagesLanguage Assessment Principles - WashbackRosmalia Kasan100% (1)

- Chen, Rogers, Hu 2004 EFL Instructors Assessment PracticesDocument30 pagesChen, Rogers, Hu 2004 EFL Instructors Assessment PracticesOriana GSNo ratings yet

- Bab 2 by EnglishDocument18 pagesBab 2 by EnglishM.Nawwaf Al-HafidzNo ratings yet

- Designing A Classroom Language Test For Junior High School StudentsDocument12 pagesDesigning A Classroom Language Test For Junior High School StudentsDhelzHahihuhehoKjmNo ratings yet

- Article 1Document22 pagesArticle 1Janneth YanzaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Strategies Related To Students' CharacteristicsDocument8 pagesTeaching Strategies Related To Students' CharacteristicsPikir Wisnu WijayantoNo ratings yet

- Qualitative Research Study: Teachers Experiences On Classroom ObservationDocument25 pagesQualitative Research Study: Teachers Experiences On Classroom ObservationLeah Carla LebrillaNo ratings yet

- Designing Portfolio Assessment of Speaking Skill For Vocational High School Students Firman WicaksonoDocument14 pagesDesigning Portfolio Assessment of Speaking Skill For Vocational High School Students Firman WicaksonoTaemin KimNo ratings yet

- 38 - The Interface Between Interlanguage, Pragmatics and Assessment - Proceedings of The 3rd Annual JALT Pan-SIG Conference.Document12 pages38 - The Interface Between Interlanguage, Pragmatics and Assessment - Proceedings of The 3rd Annual JALT Pan-SIG Conference.anhppNo ratings yet

- By Judy Kemp & Debby Toperoff: Guidelines For Portfolio AssessmentDocument27 pagesBy Judy Kemp & Debby Toperoff: Guidelines For Portfolio AssessmentJoshua LagonoyNo ratings yet

- The Influence of The Human Biorhythm in The Performance Sport ActivityDocument13 pagesThe Influence of The Human Biorhythm in The Performance Sport ActivityLarisa- Elena NegoescuNo ratings yet

- Lit CritDocument25 pagesLit CritJonna Mae Jalwin FullanteNo ratings yet

- Lab ReportDocument11 pagesLab ReportAnika O'ConnellNo ratings yet

- Case Study Prac RevisedDocument13 pagesCase Study Prac Revised20172428 YASHICA GEHLOT100% (1)

- Sip 2019-2022Document4 pagesSip 2019-2022jein_am97% (29)

- (2011) John Freedom: Energypsychology, The Future of Therapy?Document11 pages(2011) John Freedom: Energypsychology, The Future of Therapy?James Nicholls100% (1)

- Dual Relationships Between TherapistDocument18 pagesDual Relationships Between TherapistVictor Hugo EsquivelNo ratings yet

- Emerging Trends in Criminal LawDocument1 pageEmerging Trends in Criminal Lawapi-3742748No ratings yet

- What Smart Students Need Know PDFDocument14 pagesWhat Smart Students Need Know PDF007phantomNo ratings yet

- Risk Short IntroductionDocument3 pagesRisk Short IntroductionOanaMaria92No ratings yet

- Model Plan Lectie Cls.a VIII-aDocument4 pagesModel Plan Lectie Cls.a VIII-agerronimo100% (1)

- Group DynamicsDocument28 pagesGroup Dynamicskavitachordiya86100% (1)

- 9 Sports An IntroductionDocument14 pages9 Sports An IntroductionMelanie perez cortezNo ratings yet

- Organization As A Politics by Gareth MorganDocument37 pagesOrganization As A Politics by Gareth MorganJeliteng Pribadi67% (3)

- Rigor Rubric All SubjectsDocument6 pagesRigor Rubric All Subjectsapi-293015639No ratings yet

- Maryline Pimentel Professional Goals 2014-2015Document3 pagesMaryline Pimentel Professional Goals 2014-2015api-250421371No ratings yet

- Photoshop LessonDocument3 pagesPhotoshop Lessonapi-299330082No ratings yet

- Written Report - Group V - Control of AntecedentsDocument39 pagesWritten Report - Group V - Control of AntecedentsMJ FangoNo ratings yet

- Meet The Real Narcissists - Psychology TodayDocument13 pagesMeet The Real Narcissists - Psychology TodayDenisa TatuNo ratings yet

- Hiding Toys in SandDocument7 pagesHiding Toys in Sandapi-311000623No ratings yet

- Lesson Guide in Science 7 I. Objectives: Iiia-1)Document2 pagesLesson Guide in Science 7 I. Objectives: Iiia-1)Jespher GarciaNo ratings yet

- Mood Classification of Hindi Songs Based On Lyrics: December 2015Document8 pagesMood Classification of Hindi Songs Based On Lyrics: December 2015Vijay SakharaniNo ratings yet

- Stephen Krashen Second Language AcquisitionDocument4 pagesStephen Krashen Second Language AcquisitionTriya MutiaNo ratings yet

- 3rd Quarter Week 5 Day 2Document4 pages3rd Quarter Week 5 Day 2Joyce BrionesNo ratings yet

- Mukbadhir Vidhyarthiyon Ki Buddhi Eanv Samayojan Ka AdhyayanDocument12 pagesMukbadhir Vidhyarthiyon Ki Buddhi Eanv Samayojan Ka AdhyayanAnonymous CwJeBCAXpNo ratings yet

- AMB120 Bridging Cultures and AMB390 Bridging Cultures International Assessment Item 2: Report 30%Document2 pagesAMB120 Bridging Cultures and AMB390 Bridging Cultures International Assessment Item 2: Report 30%SamurdhiNo ratings yet

- IncestDocument6 pagesIncestJanenaRafalesPajulasNo ratings yet

- Teachers & Carers Guide PDFDocument11 pagesTeachers & Carers Guide PDFRosemarie FritschNo ratings yet

- Chapter IIIDocument3 pagesChapter IIIRenan S. GuerreroNo ratings yet