Professional Documents

Culture Documents

El Niño-Southern Oscillation - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia

El Niño-Southern Oscillation - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia

Uploaded by

akurilOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

El Niño-Southern Oscillation - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia

El Niño-Southern Oscillation - Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia

Uploaded by

akurilCopyright:

Available Formats

El NioSouthern Oscillation

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

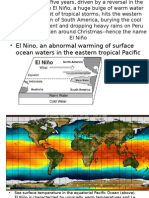

(Redirected from El nino) El NioSouthern Oscillation (pron.: /lninjo/, Spanish pronunciation: [el nio], ENSO), or El Nio/La NiaSouthern Oscillation, is a band of anomalously warm ocean water temperatures that occasionally develops off the western coast of South America and can cause climatic changes across the Pacific Ocean. The 'Southern Oscillation' refers to variations in the temperature of the surface of the tropical eastern Pacific Ocean (warming and cooling known as El Nio and La Nia, respectively) and in air surface pressure in the tropical western Pacific. The two variations are coupled: the warm oceanic phase, El Nio, accompanies high air surface pressure in the western Pacific, while the cold phase, La Nia, accompanies low air surface pressure in the western Pacific.[2][3] Mechanisms that cause the oscillation remain under study. The extremes of this climate pattern's oscillations cause extreme weather (such as floods and droughts) in many regions of the world. Developing countries dependent upon agriculture and fishing, particularly those bordering the Pacific Ocean, are the most affected. In popular usage, the El NioSouthern Oscillation is often called just "El Nio". El nio is Spanish for "the boy", and refers to the Christ child, Jesus, because periodic warming in the Pacific near South America is usually noticed around Christmas.[4]

The 1997 El Nio observed by TOPEX/Poseidon. The white areas off the tropical coasts of South and North America indicate the pool of warm water[1]

Contents

1 Definition 2 Early stages and characteristics of El Nio 3 Southern Oscillation 3.1 Walker circulation 4 Effects of ENSO's warm phase (El Nio) 4.1 South America 4.2 North America 4.3 Tropical cyclones 4.4 Elsewhere 5 Effects of ENSO's cool phase (La Nia) 5.1 Africa 5.2 Asia 5.3 South America 5.4 North America 6 Transitional phases 7 Recent occurrences 8 Remote influence on tropical Atlantic Ocean

Southern Oscillation Index timeseries 1876-2011.

NOAA graph of Global Annual Temperature Anomalies 1950 2011, showing ENSO

8 Remote influence on tropical Atlantic Ocean 9 ENSO and global warming 10 The "Modoki" or Central-Pacific El Nio debate 11 Health and social impacts of El Nio 12 Cultural history and prehistoric information 13 Climate networks 14 See also 15 References 16 Further reading 17 External links

Definition

El Nio is defined by prolonged differences in the Pacific Ocean sea surface temperatures when compared with the average value. The accepted definition is a warming or cooling of at least 0.5C (0.9F) averaged over the eastcentral tropical Pacific Ocean. Typically, this anomaly happens at irregular intervals of two to 12 years, and lasts nine months to two years.[5] The average period length is five years. When this warming or cooling occurs for only seven to nine months, it is classified as El Nio/La Nia "conditions"; when it occurs for more than that period, it is classified as El Nio/La Nia "episodes".[6] The first signs of an El Nio are: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Rise in surface pressure over the Indian Ocean, Indonesia, and Australia Fall in air pressure over Tahiti and the rest of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean Trade winds in the south Pacific weaken or head east Warm air rises near Peru, causing rain in the northern Peruvian deserts Warm water spreads from the west Pacific and the Indian Ocean to the east Pacific. It takes the rain with it, causing extensive drought in the western Pacific and rainfall in the normally dry eastern Pacific.

El Nio's warm rush of nutrient-poor water heated by its eastward passage in the Equatorial Current, replaces the cold, nutrient-rich surface water of the Humboldt Current. When El Nio conditions last for many months, extensive ocean warming and the reduction in easterly trade winds limits upwelling of cold nutrient-rich deep water, and its economic impact to local fishing for an international market can be serious.[7]

Early stages and characteristics of El Nio

Although causes are still being investigated, El Nio events begin when trade winds, part of the Walker circulation, falter for many months. A series of Kelvin wavesrelatively warm subsurface waves of water a few centimetres high and hundreds of kilometres widecross the Pacific along the equator and create a pool of warm water near South America, where ocean temperatures are normally cold due to upwelling. The weakening of the winds can also create twin cyclones, another sign of a future El Nio.[8] The Pacific Ocean is a heat reservoir that drives global wind patterns, and the resulting change in its temperature alters weather on a global scale.[9] Rainfall shifts from the western Pacific toward the Americas, while Indonesia and India become drier.[10]

Jacob Bjerknes in 1969 contributed to an understanding of ENSO by suggesting that an anomalously warm spot in the eastern Pacific can weaken the east-west temperature difference, disrupting trade winds that push warm water to the west. The result is increasingly warm water toward the east.[11] Several mechanisms have been proposed through which warmth builds up in equatorial Pacific surface waters, and is then dispersed to lower depths by an El Nio event.[12] The resulting cooler area then has to "recharge" warmth for several years before another event can take place.[13] While not a direct cause of El Nio, the Madden-Julian oscillation, or MJO, propagates rainfall anomalies eastward around the global tropics in a cycle of 3060 days, and may influence the speed of development and intensity of El Nio and La Nia in several ways.[14] For example, westerly flows between MJO-induced areas of low pressure may cause cyclonic circulations north and south of the equator. When the circulations intensify, the westerly winds within the equatorial Pacific can further increase and shift eastward, playing a role in El Nio development.[15] MaddenJulian activity can also produce eastward-propagating oceanic Kelvin waves, which may in turn be influenced by a developing El Nio, leading to a positive feedback loop.[16]

Southern Oscillation

The Southern Oscillation is the atmospheric component of El Nio. This component is an oscillation in surface air pressure between the tropical eastern and the western Pacific Ocean waters. The strength of the Southern Oscillation is measured by the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI). The SOI is computed from fluctuations in the surface air pressure difference between Tahiti and Darwin, Australia.[17] El Nio episodes are associated with negative values of the SOI, meaning the pressure difference between Tahiti and Darwin is relatively small. Low atmospheric pressure tends to occur over warm water and high pressure occurs over cold water, in part because of deep convection over the warm water. El Nio episodes are defined as sustained warming of the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean. This results in a decrease in the strength of the Pacific trade winds, and a reduction in rainfall over eastern and northern Australia.

Five-day running mean of MJO: Note how it moves eastward with time.

Walker circulation

Normal Pacific pattern: Equatorial winds gather warm water pool toward the west. Cold water upwells along South American coast. (NOAA / PMEL / TAO)

During non-El Nio conditions, the Walker circulation is seen at the surface as easterly trade winds that move water and air warmed by the sun toward the west. This also creates ocean upwelling off the coasts of Peru and Ecuador and brings nutrient-rich cold water to the surface, increasing fishing stocks. The western side of the equatorial Pacific is characterized by warm, wet, low-pressure weather as the collected moisture is dumped in the form of typhoons and thunderstorms. The ocean is some 60 cm (24 in) higher in the western Pacific as the result of this motion.[18][19][20][21]

Effects of ENSO's warm phase (El Nio)

South America

Because El Nio's warm pool feeds thunderstorms above, it creates increased rainfall across the east-central and eastern Pacific Ocean, including several portions of the South American west coast. The effects of El Nio in South America are direct and stronger than in North America. An El Nio is associated with warm and very wet weather months in April October along the coasts of northern Peru and Ecuador, causing major flooding whenever the event is strong or extreme.[22] The effects during the months of February, March, and April may become critical. Along the west coast of South America, El Nio reduces the upwelling of cold, nutrient-rich water that sustains large fish populations, which in turn sustain abundant sea birds, whose El Nio conditions: Warm water pool droppings support the fertilizer industry. This leads to fish kills off [7] approaches the South American coast. The the shore of Peru. The local fishing industry along the affected coastline can suffer during long-lasting El Nio events. The world's largest fishery collapsed due to overfishing during the 1972 El Nio Peruvian anchoveta reduction. During the 198283 event, jack mackerel and anchoveta populations were reduced, scallops increased in warmer water, but hake followed cooler water down the continental slope, while shrimp and sardines moved southward, so some catches decreased while others increased.[23] Horse mackerel have increased in the region during warm events. Shifting locations and types of fish due to changing conditions provide challenges for fishing industries. Peruvian sardines have moved during El Nio events to Chilean areas. Other conditions provide further complications, such as the government of Chile in 1991 creating restrictions on the fishing areas for self-employed fishermen and industrial fleets.

absence of cold upwelling increases warming.

La Nia conditions: Warm water is farther west than usual.

The ENSO variability may contribute to the great success of small, fast-growing species along the Peruvian coast, as periods of low population removes predators in the area. Similar effects benefit migratory birds that travel each spring from predator-rich tropical areas to distant winter-stressed nesting areas. Southern Brazil and northern Argentina also experience wetter than normal conditions, but mainly during the spring and early summer. Central Chile receives a mild winter with large rainfall, and the Peruvian-Bolivian Altiplano is sometimes exposed to unusual winter snowfall events. Drier and hotter weather occurs in parts of the Amazon River Basin, Colombia, and Central America.

North America

See also: Effects of the El NioSouthern Oscillation in the United States

Winters, during the El Nio effect, are warmer and drier than average in the Northwest, northern Midwest, and northern Mideast United States, so those regions experience reduced snowfalls. Meanwhile, significantly wetter winters are present in northwest Mexico and the southwest United States, including central and southern California, while both cooler and wetter than average winters in northeast Mexico and the southeast United States (including the Tidewater region of Virginia) occur during the El Nio phase of the oscillation.[24][25] Some believed the ice storm in January 1998, which devastated parts of southern Ontario and southern Quebec, was caused or accentuated by El Nio's warming effects.[26] El Nio warmed Vancouver for the 2010 Winter Olympics, such that the area experienced a subtropical-like winter during the games.[27] El Nio is credited with suppressing hurricanes, and made the 2009 hurricane season the least active in 12 years.[28]

Tropical cyclones

Most tropical cyclones form on the side of the subtropical ridge closer to the equator, then move poleward past the ridge axis before recurving into the main belt of the Westerlies.[29] When the subtropical ridge position shifts due to El Nio, so will the preferred tropical cyclone tracks. Areas west of Japan and Korea tend to experience much fewer SeptemberNovember tropical cyclone impacts during El Nio and neutral years. During El Nio years, the break in the subtropical ridge tends to lie near 130E, which would favor the Japanese archipelago.[30] During El Nio years, Guam's chance of a tropical cyclone impact is one-third of the long-term average.[31] The tropical Atlantic ocean experiences depressed activity due to increased vertical wind shear across the region during El Nio years.[32] On the flip side, however, the tropical Pacific Ocean east of the dateline has above-normal activity during El Nio years due to water temperatures well above average and decreased windshear.[33] Most of the recorded East Pacific category 5 hurricanes occur during El Nio years in clusters.

Regional impacts of warm ENSO episodes (El Nio)

Elsewhere

In Africa, East Africa - including Kenya, Tanzania, and the White Nile basin - experiences, in the long rains from March to May, wetter-than-normal conditions. Conditions are also drier than normal from December to February in south-central Africa, mainly in Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and Botswana. Direct effects of El Nio resulting in drier conditions occur in parts of Southeast Asia and Northern Australia, increasing bush fires, worsening haze, and decreasing air quality dramatically. Drier-than-normal conditions are also in general observed in Queensland, inland Victoria, inland New South Wales, and eastern Tasmania from June to August. Many ENSO linkages exist in the high southern latitudes around Antarctica.[34] Specifically, El Nio conditions result in high pressure anomalies over the Amundsen and Bellingshausen Seas, causing reduced sea ice and increased poleward heat fluxes in these sectors, as well as the Ross Sea. The Weddell Sea, conversely, tends to become colder with more sea ice during El Nio. The exact opposite heating and atmospheric pressure anomalies occur during La Nia.[35] This pattern of variability is known as the Antarctic dipole mode, although the Antarctic response to ENSO forcing is not ubiquitous.[35]

El Nio's effects on Europe are not entirely clear, but it is not nearly as affected as at least large parts of other continents. Some evidence indicates an El Nio may cause a wetter, cloudier winter in Northern Europe and a milder, drier winter in the Mediterranean Sea region. The El Nio winter of 2006/2007 was unusually mild in Europe, and the Alps recorded very little snow coverage that season.[36] In most recent times, Singapore experienced the driest February in 2010 since records begins in 1869, with only 6.3 mm of rain falling in the month and temperatures hitting as high as 35C on 26 February. The years 1968 and 2005 had the next driest Februaries, when 8.4 mm of rain fell.[37]

Effects of ENSO's cool phase (La Nia)

Main article: La Nia La Nia is the name for the cold phase of ENSO, during which the cold pool in the eastern Pacific intensifies and the trade winds strengthen. The name La Nia originates from Spanish, meaning "the girl", analogous to El Nio meaning "the boy". It has also in the past been called anti-El Nio, and El Viejo (meaning "the old man").[38]

Africa

La Nia results in wetter-than-normal conditions in Southern Africa from December to February, and drierthan-normal conditions over equatorial East Africa over the same period.[39]

Sea surface skin temperature anomalies in November 2007 showing La Nia conditions

Asia

During La Nia years, the formation of tropical cyclones, along with the subtropical ridge position, shifts westward across the western Pacific ocean, which increases the landfall threat to China.[30] In March 2008, La Nia caused a drop in sea surface temperatures over Southeast Asia by 2C. It also caused heavy rains over Malaysia, the Philippines, and Indonesia.[40]

South America

During a time of La Nia, drought plagues the coastal regions of Peru and Chile.[41] From December to February, northern Brazil is wetter than normal.[41]

North America

La Nia causes mostly the opposite effects of El Nio, above-average precipitation across the northern Midwest, the northern Rockies, Northern California, and the Pacific Northwest's southern and eastern regions. Meanwhile, precipitation in the southwestern and southeastern states is below average.[42]

La Nias occurred in 1904, 1908, 1910, 1916, 1924, 1928, 1938, 1950, 1955, 1964, 1970, 1973, 1975, 1988, 1995, 1998, 2010, and 2011.[43] In Canada, La Nia will, in general, cause a cooler, snowier winter, such as the near-record-breaking amounts of snow recorded in the La Nia winter of 2007/2008 in Eastern Canada.[44] [45] The 2010-2011 La Nia was one of the strongest ever observed. The effect on Eastern Australia was devastating.[46]

Transitional phases

Transitional phases at the onset or departure of El Nio or La Nia can also be important factors on global weather by affecting teleconnections. Significant episodes, known as Trans-Nio, are measured by the Trans-Nio index (TNI) (http://www.cgd.ucar.edu/cas/catalog/climind/TNI_N34/).[47] Examples of affected short-time climate in North America include precipitation in the Northwest US[48] and intense tornado activity in the contiguous US.[49]

Recent occurrences

A strong La Nia episode occurred during 19881989. La Nia Regional impacts of La Nia. also formed in 1995 and from 19982000, and a minor one from 20002001. In recent times, an occurrence of El Nio started in September 2006[50] and lasted until early 2007.[51] From June 2007 on, data indicated a moderate La Nia event, which strengthened in early 2008 and weakened before the start of 2009; the 20072008 La Nia event was the strongest since the 19881989 event. The strength of the La Nia made the 2008 Atlantic hurricane season one of the most active since 1944; 16 named storms had winds of at least 39 mph (63 km/h), eight of which became 74 mph (119 km/h) or greater hurricanes.[28] According to NOAA, El Nio conditions were in place in the equatorial Pacific Ocean starting June 2009, peaking in JanuaryFebruary. Positive SST anomalies (El Nio) lasted until May 2010. SST anomalies then transitioned into the negative (La Nia) and have now transitioned back to ENSO-neutral during April 2012. In early July, NOAA stated that El Nio conditions have a 50+% chance of developing during the Northern Hemisphere summer. As the 2012, Northern Hemisphere summer started to draw to a close, NOAA stated that El Nio conditions are likely to develop in August or September.[45]

Remote influence on tropical Atlantic Ocean

A study of climate records has shown that El Nio events in the equatorial Pacific are generally associated with a warm tropical North Atlantic in the following spring and summer.[52] About half of El Nio events persist sufficiently into the spring months for the Western Hemisphere Warm Pool to become unusually large in summer.[53] Occasionally, El Nio's effect on the Atlantic Walker circulation over South America strengthens the easterly trade winds in the western equatorial Atlantic region. As a result, an unusual cooling may occur in the eastern equatorial Atlantic in spring and summer following El Nio peaks in winter.[54] Cases of El Nio-type events in both oceans simultaneously have been linked to severe famines related to the extended failure of monsoon rains.[55]

ENSO and global warming

During the last several decades, the number of El Nio events increased, and the number of La Nia events decreased,[56] although observation of ENSO for much longer is needed to detect robust changes.[57] The question is whether this is a random fluctuation or a normal instance of variation for that phenomenon or the result of global climate changes toward global warming. The studies of historical data show the recent El Nio variation is most likely linked to global warming. For example, one of the most recent results, even after subtracting the positive influence of decadal variation, is shown to be possibly present in the ENSO trend,[58] the amplitude of the ENSO variability in the observed data still increases, by as much as 60% in the last 50 years.[59] The exact changes happening to ENSO in the future is uncertain:[60] Different models make different predictions.[61] It may be that the observed phenomenon of more frequent and stronger El Nio events occurs only in the initial phase of the global warming, and then (e.g., after the lower layers of the ocean get warmer, as well), El Nio will become weaker than it was.[62] It may also be that the stabilizing and destabilizing forces influencing the phenomenon will eventually compensate for each other.[63] More research is needed to provide a better answer to that question. The ENSO is considered to be a potential tipping element in Earth's climate.[64]

The "Modoki" or Central-Pacific El Nio debate

The traditional Nio, also called Eastern Pacific (EP) El Nio,[65] involves temperature anomalies in the Eastern Pacific. However, in the last two decades, nontraditional El Nios were observed, in which the usual place of the temperature anomaly (Nino 1 and 2) is not affected, but an anomaly arises in the central Pacific (Nino 3.4).[66] The phenomenon is called Central Pacific (CP) El Nio,[65] "dateline" El Nio (because the anomaly arises near the dateline), or El Nio "Modoki" (Modoki is Japanese for "similar, but different").[67] The effects of the CP El Nio are different from those of the traditional EP El Nioe.g., the new El Nio leads to more hurricanes more frequently making landfall in the Atlantic.[68] The recent discovery of El Nio Modoki has some scientists believing it to be linked to global warming.[69] However, satellite data go back only to 1979. More research must be done to find the correlation and study past El Nio episodes.

Map showing Nino3.4 and other index regions

There is also a scientific debate on the very existence of this "new" ENSO. Indeed, a number of studies dispute the reality of this statistical distinction or its increasing occurrence, or both, either arguing the reliable record is too short to detect such a distinction,[70][71] finding no distinction or trend using other statistical approaches,[72][73][74][75][76] or that other types should be distinguished, such as standard and extreme El Nios.[77][78] Following the asymmetric nature of the warm and cold phases of ENSO, a study could not identify such distinctions for La Nia, both in observations and in the climate models.[79]

Map of Atlantic major hurricanes during post-"Modoki" seasons, including 1987, 1992, 1995, 2003 and 2005.

The first recorded El Nio that originated in the central Pacific and moved toward the east was in 1986.[80] There is no scientific consensus on how/if climate change may affect ENSO.[81]

Health and social impacts of El Nio

Extreme weather conditions related to the El Nio cycle correlate with changes in the incidence of epidemic diseases. For example, the El Nio cycle is associated with increased risks of some of the diseases transmitted by mosquitoes, such as malaria, dengue, and Rift Valley fever. Cycles of malaria in India, Venezuela, and Colombia have now been linked to El Nio. Outbreaks of another mosquito-transmitted disease, Australian encephalitis (Murray Valley encephalitisMVE), occur in temperate south-east Australia after heavy rainfall and flooding, which are associated with La Nia events. A severe outbreak of Rift Valley fever occurred after extreme rainfall in north-eastern Kenya and southern Somalia during the 199798 El Nio.[82] ENSO may be linked to civil conflicts. Scientists at The Earth Institute of Columbia University, having analyzed data from 1950 to 2004, suggest ENSO may have had a role in 21% of all civil conflicts since 1950, with the risk of annual civil conflict doubling from 3% to 6% in countries affected by ENSO during El Nio years relative to La Nia years.[83][84]

Cultural history and prehistoric information

ENSO conditions have occurred at two- to seven-year intervals for at least the past 300 years, but most of them have been weak. Evidence is also strong for El Nio events during the early Holocene epoch 10,000 years ago.[85] El Nio affected pre-Columbian Incas [86] and may have led to the demise of the Moche and other pre-Columbian Peruvian cultures.[87] A recent study suggests a strong El-Nio effect between 1789 and 1793 caused poor crop yields in Europe, which in turn helped touch off the French Revolution.[88] The extreme weather produced by El Nio in 187677 gave rise to the most deadly famines of the 19th century.[89] The 1876 famine alone in northern China killed up to 13 million people.[90] An early recorded mention of the term "El Nio" to refer to climate occurred in 1892, when Captain Camilo Carrillo told the geographical society congress in Lima that Peruvian sailors named the warm northerly current "El Nio" because it was most noticeable around Christmas. The phenomenon had long been of interest because of its effects on the guano industry and other enterprises that depend on biological productivity of the sea.

Average equatorial Pacific temperatures

Charles Todd, in 1893, suggested droughts in India and Australia tended to occur at the same time; Norman Lockyer noted the same in 1904. An El Nio connection with flooding was reported in 1895 by Pezet and Eguiguren. In 1924, Gilbert Walker (for whom the Walker circulation is named) coined the term "Southern Oscillation".

The major 198283 El Nio led to an upsurge of interest from the scientific community. The period 19901994 was unusual in that El Nios have rarely occurred in such rapid succession.[91] An especially intense El Nio event in 1998 caused an estimated 16% of the world's reef systems to die. The event temporarily warmed air temperature by 1.5C, compared to the usual increase of 0.25C associated with El Nio events.[92] Since then, mass coral bleaching has become common worldwide, with all regions having suffered "severe bleaching".[93] Major ENSO events were recorded in the years 179093, 1828, 187678, 1891, 192526, 197273, 198283, 199798 and 20092010,[55] with 1997-1998 being one of the strongest ever.[94]

Climate networks

Analysis of El Nio events using climate networks shows the dynamics of the climate network is very sensitive to El Nio events. Many links in the network fail during El Nio events.[95]

See also

Arctic oscillation Benguela Nio Indian Ocean Dipole Pacific Decadal Oscillation North Atlantic Oscillation

References

1. ^ "Independent NASA Satellite Measurements Confirm El Nio is Back and Strong" (http://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/releases/97/elninoup.html). NASA/JPL. 2. ^ Climate Prediction Center (2005-12-19). "Frequently Asked Questions about El Nio and La Nia" (http://www.cpc.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/ensostuff/ensofaq.shtml#DIFFER). National Centers for Environmental Prediction. Retrieved 2009-07-17. 3. ^ K.E. Trenberth, P.D. Jones, P. Ambenje, R. Bojariu , D. Easterling, A. Klein Tank, D. Parker, F. Rahimzadeh, J.A. Renwick, M. Rusticucci, B. Soden and P. Zhai. "Observations: Surface and Atmospheric Climate Change" (http://www.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg1/en/ch3.html). In Solomon, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K.B. Averyt, M. Tignor and H.L. Miller. Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 235336. 4. ^ "El Nio Information" (http://www.dfg.ca.gov/marine/elnino.asp). California Department of Fish and Game, Marine Region. 5. ^ Climate Prediction Center (2005-12-19). "ENSO FAQ: How often do El Nio and La Nia typically occur?" (http://www.cpc.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/ensostuff/ensofaq.shtml#HOWOFTEN). National Centers for Environmental Prediction. Retrieved 2009-07-26. 6. ^ National Climatic Data Center (June 2009). "El Nio / Southern Oscillation (ENSO) June 2009" (http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/climate/research/enso/?year=2009&month=6&submitted=true). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2009-07-26. 7. ^ a b WW2010 (1998-04-28). "El Nio" (http://ww2010.atmos.uiuc.edu/(Gh)/guides/mtr/eln/home.rxml). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Retrieved 2009-07-17. 8. ^ Tim Liu (2005-09-06). "El Nio Watch from Space" (http://airsea-www.jpl.nasa.gov/ENSO/welcome.html). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 2010-05-31. 9. ^ Stewart, Robert (2009-01-06). "El Nio and Tropical Heat"

9. ^ Stewart, Robert (2009-01-06). "El Nio and Tropical Heat" (http://oceanworld.tamu.edu/resources/oceanography-book/heatbudgets.htm). Our Ocean Planet: Oceanography in the 21st Century. Department of Oceanography, Texas A&M University. Retrieved 2009-07-25. 10. ^ Dr. Tony Phillips (2002-03-05). "A Curious Pacific Wave" (http://science.nasa.gov/headlines/y2002/05mar_kelvinwave.htm). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved 2009-07-24. 11. ^ Nova (1998). "1969" (http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/elnino/reach/1969.html). Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 2009-07-24. 12. ^ De-Zheng Sun; James B. Elsner (2007). Nonlinear Dynamics in Geosciences: 29 The Role of El NioSouthern Oscillation in Regulating its Background State (http://www.springerlink.com/content/r48078945n5w086v/). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-34918-3 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2F978-0-387-34918-3). ISBN 978-0-38734917-6. Retrieved 2009-07-24. 13. ^ Soon-Il An and In-Sik Kang (2000). "A Further Investigation of the Recharge Oscillator Paradigm for ENSO Using a Simple Coupled Model with the Zonal Mean and Eddy Separated" (http://ams.allenpress.com/perlserv/? request=get-document&doi=10.1175%2F1520-0442(2000)013%3C1987%3AAFIOTR%3E2.0.CO%3B2). Journal of Climate 13 (11): 198793. Bibcode:2000JCli...13.1987A (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2000JCli...13.1987A). doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2000)013<1987:AFIOTR>2.0.CO;2 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1175%2F15200442%282000%29013%3C1987%3AAFIOTR%3E2.0.CO%3B2). ISSN 1520-0442 (//www.worldcat.org/issn/1520-0442). Retrieved 2009-07-24. 14. ^ Jon Gottschalck and Wayne Higgins (2008-02-16). "Madden Julian Oscillation Impacts" (http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/precip/CWlink/MJO/MJO_1page_factsheet.pdf). Climate Prediction Center. Retrieved 2009-07-24. 15. ^ Air-Sea Interaction & Climate (2005-09-06). "El Nio Watch from Space" (http://airseawww.jpl.nasa.gov/ENSO/welcome.html). Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology. Retrieved 2009-07-17. 16. ^ Eisenman, Ian; Yu, Lisan; Tziperman, Eli (2005). "Westerly Wind Bursts: ENSO's Tail Rather than the Dog?". Journal of Climate 18 (24): 522438. Bibcode:2005JCli...18.5224E (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2005JCli...18.5224E). doi:10.1175/JCLI3588.1 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1175%2FJCLI3588.1). 17. ^ "Climate glossary - Southern Oscilliation Index (SOI)" (http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/glossary/soi.shtml). Bureau of Meteorology (Australia). 2002-04-03. Retrieved 2009-12-31. 18. ^ Pidwirny, Michael (2006-02-02). "Chapter 7: Introduction to the Atmosphere" (http://www.physicalgeography.net/fundamentals/7z.html). Fundamentals of Physical Geography. physicalgeography.net. Retrieved 2006-12-30. 19. ^ "Envisat watches for La Nia" (http://web.archive.org/web/20080424113710/http://www.bnsc.gov.uk/content.aspx?nid=5989). BNSC via the Internet Wayback Machine. 2011-01-09. Archived from the original (http://www.bnsc.gov.uk/content.aspx? nid=5989) on 2008-04-24. Retrieved 2007-07-26. 20. ^ "The Tropical Atmosphere Ocean Array: Gathering Data to Predict El Nio" (http://celebrating200years.noaa.gov/datasets/tropical/welcome.html). Celebrating 200 Years. NOAA. 2007-01-08. Retrieved 2007-07-26. 21. ^ "Ocean Surface Topography" (http://sealevel.jpl.nasa.gov/gallery/presentations/oceanography-101/ocean101slide14.html). Oceanography 101. JPL. 2006-07-05. Retrieved 2007-07-26."Annual Sea Level Data Summary Report July 2005 - June 2006" (http://web.archive.org/web/20070807235141/http://www.bom.gov.au/fwo/IDO60202/IDO60202.2006.pdf) (PDF). The Australian Baseline Sea Level Monitoring Project. Bureau of Meteorology. Archived from the original (http://www.bom.gov.au/fwo/IDO60202/IDO60202.2006.pdf) on 2007-08-07. Retrieved 2007-07-26. 22. ^ "Atmospheric Consequences of El Nio" (http://ww2010.atmos.uiuc.edu/%28Gh%29/guides/mtr/eln/atms.rxml). University of Illinois. Retrieved 2010-05-31. 23. ^ Pearcy, W. G.; Schoener, A. (1987). "Changes in the marine biota coincident with the 1982-1983 El Nio in the northeastern subarctic Pacific Ocean" (http://www.agu.org/pubs/crossref/1987/JC092iC13p14417.shtml). Journal of Geophysical Research 92 (C13): 1441728. Bibcode:1987JGR....9214417P (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1987JGR....9214417P). doi:10.1029/JC092iC13p14417 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1029%2FJC092iC13p14417).

(http://dx.doi.org/10.1029%2FJC092iC13p14417). 24. ^ Climate Prediction Center. Average October-December (3-month) Temperature Rankings During ENSO Events. (http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/predictions/threats2/enso/elnino/UStrank/ond.gif) Retrieved on 2008-0416. 25. ^ Climate Prediction Center. Average December-February (3-month) Temperature Rankings During ENSO Events. (http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/predictions/threats2/enso/elnino/UStrank/djf.gif) Retrieved on 2008-0416. 26. ^ http://www.davidsuzuki.org/Climate_Change/Impacts/Extreme_Weather/El_Nino.asp 27. ^ Vancouver 2010 to Be Warmest Winter Olympics Yet (http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2010/02/100212-vancouver-2010-warmest-winter-olympics) 28. ^ a b Brian K. Sullivan (2010-05-06). "El Nio Warning Will Fade Out by June, U.S. Says (Update 1)" (http://www.businessweek.com/news/2010-05-06/el-nino-warming-will-fade-out-by-june-u-s-says-update1-.html). Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 2010-05-31. 29. ^ Joint Typhoon Warning Center (2006). 3.3 JTWC Forecasting Philosophies. (http://www.nrlmry.navy.mil/forecaster_handbooks/Philippines2/Forecasters%20Handbook%20for%20the%20Phil ippine%20Islands%20and%20Surrounding%20Waters%20Typhoon%20Forecasting.3.pdf) United States Navy. Retrieved on 2007-02-11. 30. ^ a b M. C. Wu, W. L. Chang, and W. M. Leung (2003). Impacts of El NioSouthern Oscillation Events on Tropical Cyclone Landfalling Activity in the Western North Pacific. (http://ams.allenpress.com/perlserv/? request=get-document&doi=10.1175%2F1520-0442(2004)017%3C1419:IOENOE%3E2.0.CO%3B2) Journal of Climate: pp. 14191428. Retrieved on 2007-02-11. 31. ^ Pacific ENSO Applications Climate Center. Pacific ENSO Update: 4th Quarter, 2006. Vol. 12 No. 4. (http://www.soest.hawaii.edu/MET/Enso/peu/2006_4th/guam_cnmi.htm) Retrieved on 2008-03-19. 32. ^ Edward N. Rappaport (September 1999). "Atlantic Hurricane Season of 1997" (http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/general/lib/lib1/nhclib/mwreviews/1997.pdf). Monthly Weather Review 127 (9): 2012. Bibcode:1999MWRv..127.2012R (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1999MWRv..127.2012R). doi:10.1175/15200493(1999)127<2012:AHSO>2.0.CO;2 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1175%2F15200493%281999%29127%3C2012%3AAHSO%3E2.0.CO%3B2). ISSN 1520-0493 (//www.worldcat.org/issn/15200493). Retrieved 2009-07-18. 33. ^ http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/Epac_hurr/background_information.html 34. ^ Turner, John (2004). "The El NioSouthern Oscillation and Antarctica". International Journal of Climatology 24: 131. Bibcode:2004IJCli..24....1T (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2004IJCli..24....1T). doi:10.1002/joc.965 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fjoc.965). 35. ^ a b Yuan, Xiaojun (2004). "ENSO-related impacts on Antarctic sea ice: a synthesis of phenomenon and mechanisms". Antarctic Science 16 (4): 415425. doi:10.1017/S0954102004002238 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1017%2FS0954102004002238). 36. ^ "Concern over Europe 'snow crisis'" (http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6185345.stm). BBC News. 2006-12-17. Retrieved 2010-05-01. 37. ^ http://www.channelnewsasia.com/stories/singaporelocalnews/view/1040778/1/.html 38. ^ Tropical Atmosphere Ocean project (2008-03-24). "What is La Nia?" (http://www.pmel.noaa.gov/tao/elnino/lanina-story.html). Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory. Retrieved 2009-07-17. 39. ^ http://www.scoop.co.nz/stories/WO1010/S00173/la-nina-weather-likely-to-last-for-months.htm 40. ^ Hong, Lynda (2008-03-13). "Recent heavy rain not caused by global warming" (http://www.channelnewsasia.com/stories/singaporelocalnews/view/334735/1/.html). Channel NewsAsia. Retrieved 2008-06-22. 41. ^ a b "La Nia follows El Nio, the GLOBE El Nio Experiment continues" (http://classic.globe.gov/fsl/html/templ.cgi?butler_lanina&lang=en). Retrieved 2010-05-31. 42. ^ "ENSO Diagnostic Discussion" (http://www.cpc.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/enso_advisory/ensodisc.html). Climate Prediction Center. 2008-06-05. 43. ^ "La Nia Information" (http://www.publicaffairs.noaa.gov/lanina.html). Retrieved 2010-05-31. 44. ^ http://www.ec.gc.ca/doc/smc-msc/2008/s3_eng.html 45. ^ a b http://www.cpc.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/lanina/enso_evolution-status-fcsts-web.pdf

45. ^ a b http://www.cpc.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/lanina/enso_evolution-status-fcsts-web.pdf 46. ^ http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/enso/feature/ENSO-feature.shtml 47. ^ Trenberth, Kevin E.; D. P. Stepaniak (2001). "Indices of El Nio Evolution". J. Climate 14 (8): 1697701. doi:10.1175/1520-0442(2001)014<1697:LIOENO>2.0.CO;2 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1175%2F15200442%282001%29014%3C1697%3ALIOENO%3E2.0.CO%3B2). 48. ^ Kennedy, Adam M.; D. C. Garen, R. W. Koch (2009). "The association between climate teleconnection indices and Upper Klamath seasonal streamflow: Trans-Nio Index". Hydrol. Process. 23 (7): 97384. doi:10.1002/hyp.7200 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1002%2Fhyp.7200). 49. ^ Lee, Sang-Ki; R. Atlas, D. Enfield, C. Wang, and H. Liu (2012). "Is there an optimal ENSO pattern that enhances large-scale atmospheric processes conducive to tornado outbreaks in the U.S?". J. Climate. in press. doi:10.1175/JCLI-D-12-00128.1 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1175%2FJCLI-D-12-00128.1). 50. ^ Pastor, Rene (2006-09-14). "El Nio climate pattern forms in Pacific Ocean" (http://www.usatoday.com/weather/climate/2006-09-13-el-nino_x.htm). USA Today. 51. ^ Borenstein, Seth (2007-02-28). "There Goes El Nio, Here Comes La Nia" (http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2007/02/28/tech/main2523483.shtml). CBS News. 52. ^ David B. Enfield and Dennis A. Mayer (1997). "Tropical Atlantic sea surface temperature variability and its relation to El NioSouthern Oscillation" (http://www.agu.org/pubs/crossref/1997/96JC03296.shtml). Journal of Geophysical Research 102 (C1): 929945. Bibcode:1997JGR...102..929E (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1997JGR...102..929E). doi:10.1029/96JC03296 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1029%2F96JC03296). Retrieved 2009-11-29. 53. ^ Sang-Ki Lee, Chunzai Wang and David B. Enfield (2008). "Why do some El Nios have no impact on tropical North Atlantic SST?" (http://www.agu.org/pubs/crossref/2008/2008GL034734.shtml). Geophysical Research Letters 35 (L16705): L16705. Bibcode:2008GeoRL..3516705L (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2008GeoRL..3516705L). doi:10.1029/2008GL034734 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1029%2F2008GL034734). Retrieved 2009-11-29. 54. ^ M. Latif and A. Grtzner (2000). "The equatorial Atlantic oscillation and its response to ENSO" (http://www.springerlink.com/content/1hjeatc9jjlb0lh2/?p=038dacb0cb4140679f406a9ebed3304a&pi=0). Climate Dynamics 16 (23): 213218. Bibcode:2000ClDy...16..213L (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2000ClDy...16..213L). doi:10.1007/s003820050014 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs003820050014). Retrieved 2009-11-29. 55. ^ a b Davis, Mike (2001). Late Victorian Holocausts: El Nio Famines and the Making of the Third World. London: Verso. p. 271. ISBN 1-85984-739-0. 56. ^ Trenberth, Kevin E.; Hoar, Timothy J. (January 1996). "The 19901995 El NioSouthern Oscillation event: Longest on record". Geophysical Research Letters 23 (1): 57&;60. Bibcode:1996GeoRL..23...57T (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1996GeoRL..23...57T). doi:10.1029/95GL03602 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1029%2F95GL03602). 57. ^ Wittenberg, A. T. (2009), Are historical records sufficient to constrain ENSO simulations?, Geophys. Res. Lett., 36, L12702, doi:10.1029/2009GL038710. 58. ^ Fedorov, Alexey V.; Philander, S. George (2000). "Is El Nio Changing?". Science 288 (5473): 19972002. Bibcode:2000Sci...288.1997F (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2000Sci...288.1997F). doi:10.1126/science.288.5473.1997 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1126%2Fscience.288.5473.1997). PMID 10856205 (//www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10856205). 59. ^ Zhang, Qiong; Guan, Yue; Yang, Haijun (2008). "ENSO Amplitude Change in Observation and Coupled Models". Advances in Atmospheric Sciences 25 (3): 3316. Bibcode:2008AdAtS..25..361Z (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2008AdAtS..25..361Z). doi:10.1007/s00376-008-0361-5 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs00376-008-0361-5). 60. ^ Collins, M., et al., (2010): The impact of global warming on the tropical Pacific Ocean and El Nio. Nature Geosci., 3 (6), 391397, URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ngeo868 61. ^ Merryfield, William J. (2006). "Changes to ENSO under CO2 Doubling in a Multimodel Ensemble" (http://www.ocgy.ubc.ca/~yzq/books/paper5_IPCC_revised/Merryfield2006.pdf). Journal of Climate 19 (16): 400927. Bibcode:2006JCli...19.4009M (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2006JCli...19.4009M). doi:10.1175/JCLI3834.1 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1175%2FJCLI3834.1). 62. ^ Meehl, G. A.; Teng, H.; Branstator, G. (2006). "Future changes of El Nio in two global coupled climate models". Climate Dynamics 26 (6): 549. Bibcode:2006ClDy...26..549M

63. 64.

65.

66.

67. 68.

69.

70. 71. 72. 73. 74. 75. 76.

77. 78. 79. 80. 81.

models". Climate Dynamics 26 (6): 549. Bibcode:2006ClDy...26..549M (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2006ClDy...26..549M). doi:10.1007/s00382-005-0098-0 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1007%2Fs00382-005-0098-0). ^ Philip, S.; Van Oldenborgh, G. J. (2006). "Shifts in ENSO coupling processes under global warming". Geophysical Research Letters 33 (11). doi:10.1029/2006GL026196 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1029%2F2006GL026196). ^ Lenton, T. M.; Held, H.; Kriegler, E.; Hall, J. W.; Lucht, W.; Rahmstorf, S.; Schellnhuber, H. J. (2008). "Tipping Elements in the Earth's Climate System". PNAS 105 (6): 17861793. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705414105 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1073%2Fpnas.0705414105). ^ a b Kao, Hsun-Ying and Jin-Yi Yu (2009). "Contrasting Eastern-Pacific and Central-Pacific Types of ENSO" (http://ams.allenpress.com/perlserv/?request=get-abstract&doi=10.1175%2F2008JCLI2309.1). Journal of Climate 22 (3): 615632. Bibcode:2009JCli...22..615K (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2009JCli...22..615K). doi:10.1175/2008JCLI2309.1 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1175%2F2008JCLI2309.1). More than one of | w o r k =and | j o u r n a l =specified (help) ^ Larkin, N. K.; Harrison, D. E. (2005). "On the definition of El Nio and associated seasonal average U.S. Weather anomalies". Geophysical Research Letters 32 (13): L13705. Bibcode:2005GeoRL..3213705L (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2005GeoRL..3213705L). doi:10.1029/2005GL022738 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1029%2F2005GL022738). ^ Michele Marra (2002-01-01). Modern Japanese Aesthetics: A Reader (http://books.google.com/? id=CDwaTsno9IMC). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-2077-0. ^ Hye-Mi Kim, Peter J. Webster, & Judith A. Curry; Webster (2009). "Impact of Shifting Patterns of Pacific Ocean Warming on North Atlantic Tropical Cyclones" (http://www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/abstract/325/5936/77). Science 335 (5936): 7780. Bibcode:2009Sci...325...77K (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2009Sci...325...77K). doi:10.1126/science.1174062 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1126%2Fscience.1174062). PMID 19574388 (//www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19574388). More than one of | w o r k =and | j o u r n a l =specified (help) ^ Yeh, Sang-Wook; Kug, Jong-Seong; Dewitte, Boris; Kwon, Min-Ho; Kirtman, Ben P.; Jin, Fei-Fei (September 2009). "El Nio in a changing climate". Nature 461 (7263): 5114. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..511Y (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2009Natur.461..511Y). doi:10.1038/nature08316 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnature08316). PMID 19779449 (//www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19779449). ^ Nicholls, N., (2008): Recent trends in the seasonal and temporal behaviour of the El Nio Southern Oscillation. Geophysical Research Letters, 35(L19703) ^ McPhaden, M. J., T. Lee, and D. McClurg (2011), El Nio and its relationship to changing background conditions in the tropical Pacific Ocean, Geophys. Res. Lett., 38, L15709, doi:10.1029/2011GL048275 ^ Giese, B. S., and S. Ray (2011): El Nio variability in simple ocean data assimilation (SODA), 18712008, J. Geophys. Res., 116, C02024 ^ Newman, M., S.-I. Shin, and M. A. Alexander (2011), Natural variation in ENSO flavors, Geophys. Res. Lett., 38, L14705, doi:10.1029/2011GL047658. ^ Yeh, S. W., B. P. Kirtman, J. S. Kug, W. Park, and M. Latif (2011), Natural variability of the central Pacific El Nio event on multi centennial timescales, Geophys. Res. Lett., 38, L02704, doi:10.1029/2010GL045886 ^ Na et al. (2011): Statistical simulations of the future 50-year statistics of cold-tongue El Nio and warm-pool El Nio. Asia-Pacific J. Atmos. Sci., 47(3), 223-233 ^ L'Heureux, M., Collins, D., & Hu, Z.-Z. (2012). Linear trends in sea surface temperature of the tropical Pacific Ocean and implications for the El Nio-Southern Oscillation. Climate Dynamics, 114. doi:10.1007/s00382-0121331-2 ^ Lengaigne, M. & Vecchi, G. (2010). Contrasting the termination of moderate and extreme El Nio events in coupled general circulation models Climate Dynamics, 35, 299-313 ^ Takahashi, K., A. Montecinos, K. Goubanova, and B. Dewitte, (2011): ENSO regimes: Reinterpreting the canonical and Modoki El Nio. Geophys. Res. Lett., 38, L10704, doi:10.1029/2011GL047364. ^ Kug, J.-S., F.-F. Jin, and S.-I. An, 2009: Two types of El Nio events: Cold Tongue El Nio and Warm Pool El Nio. J. Climate, 22, 1499 -1515. ^ S. George Philander (2004). Our Affair with El Nio: How We Transformed an Enchanting Peruvian Current Into a Global Climate Hazard. ISBN 978-0-691-11335-7. ^ Collins, M., S-I An, W. Cai, A. Ganachaud, E. Guilyardi, F-F Jin, M. Jochum, M. Lengaigne, S. Power, A. Timmermann, G. Vecchi and A. Wittenberg (2010). The Impact of Global Warming on the Tropical Pacific and El

82. 83.

84.

85.

86. 87. 88.

89. 90. 91.

92.

93.

94.

95.

Timmermann, G. Vecchi and A. Wittenberg (2010). The Impact of Global Warming on the Tropical Pacific and El Nio. Nature Geoscience, 3, 391-397 ^ "El Nio and its health impact" (http://www.allcountries.org/health/el_nino_and_its_health_impact.html). Health Topics A to Z. Retrieved 2011-01-01.. ^ Hsiang, S. M. , Meng, K. C. & Cane, M. A. (2011). "Civil conflicts are associated with the global climate" (http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v476/n7361/full/nature10311.html). Nature 476 (7361): 438441. Bibcode:2011Natur.476..438H (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2011Natur.476..438H). doi:10.1038/nature10311 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnature10311). ^ Quirin Schiermeier (2011). "Climate cycles drive civil war" (http://www.nature.com/news/2011/110824/full/news.2011.501.html). Nature 476: 406407. doi:10.1038/news.2011.501 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2Fnews.2011.501). ^ Carr, Matthieu et al. (2005). "Strong El Nio events during the early Holocene: stable isotope evidence from Peruvian sea shells". The Holocene 15 (1): 427. doi:10.1191/0959683605h1782rp (http://dx.doi.org/10.1191%2F0959683605h1782rp). ^ "El Nino here to stay" (http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/25433.stm). BBC News. Retrieved 2010-05-01. ^ Brian Fagan (1999). Floods, Famines and Emporers: El Nio and the Fate of Civilizations. Basic Books. pp. 119138. ISBN 0-465-01120-9. ^ Grove, Richard H. (1998). "Global Impact of the 178993 El Nio". Nature 393 (6683): 3189. Bibcode:1998Natur.393..318G (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1998Natur.393..318G). doi:10.1038/30636 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1038%2F30636). ^ " Grda, C.: Famine: A Short History (http://press.princeton.edu/chapters/s8857.html)". Princeton University Press. ^ Dimensions of need People and populations at risk (http://www.fao.org/docrep/U8480E/U8480E05.htm). Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). ^ Trenberth, Kevin E.; Hoar, Timothy J. (1996). "The 19901995 El NioSouthern Oscillation Event: Longest on Record" (http://www.agu.org/pubs/crossref/1996/95GL03602.shtml). Geophysical Research Letters 23 (1): 5760. Bibcode:1996GeoRL..23...57T (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1996GeoRL..23...57T). doi:10.1029/95GL03602 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1029%2F95GL03602). ^ Trenberth, K. E. et al. (2002). "Evolution of El Nio Southern Oscillation and global atmospheric surface temperatures". Journal of Geophysical Research 107 (D8): 4065. Bibcode:2002JGRD..107.4065T (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2002JGRD..107.4065T). doi:10.1029/2000JD000298 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1029%2F2000JD000298). ^ Marshall, Paul; Schuttenberg, Heidi (2006). A reef manager's guide to coral bleaching (http://coris.noaa.gov/activities/reef_managers_guide/). Townsville, Qld.: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. ISBN 1-876945-40-0. ^ ENSO Cycle: Recent Evolution, Current Status and Predictions (http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/lanina/enso_evolution-status-fcsts-web.pdf). National Weather Service, Climate Prediction Center. ^ K. Yamasaki, A. Gozolchiani, S. Havlin (2008). "Climate networks around the globe are significantly affected by El Nino" (http://havlin.biu.ac.il/Publications.php? keyword=Climate+networks+around+the+globe+are+significantly+affected+by+El+Nino&year=*&match=all). Phys. Rev. Lett 100: 228501. Bibcode:2008PhRvL.100c8501L (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2008PhRvL.100c8501L). doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.038501 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1103%2FPhysRevLett.100.038501).

Kuenzer, C.; Zhao, D.; Scipal, K.; Sabel, D.; Naeimi, V.; Bartalis, Z.; Hasenauer, S.; Mehl, H.; Dech, S.; Waganer, W. (2009). "El Nio southern oscillation influences represented in ERS scatterometer-derived soil moisture data". Applied Geography. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2009.04.004 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.apgeog.2009.04.004).

Further reading

Caviedes, Csar N. (2001). El Nio in History: Storming Through the Ages. Gainesville: University of Florida Press. ISBN 0-8130-2099-9. Fagan, Brian M. (1999). Floods, Famines, and Emperors: El Nio and the Fate of Civilizations. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-7126-6478-5. Glantz, Michael H. (2001). Currents of change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-52178672-X. Philander, S. George (1990). El Nio, La Nia and the Southern Oscillation. San Diego: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-553235-0. Trenberth, Kevin E. (1997). "The definition of El Nio" (http://ams.allenpress.com/perlserv/?request=resloc&uri=urn%3Aap%3Apdf%3Adoi%3A10.1175%2F15200477%281997%29078%3C2771%3ATDOENO%3E2.0.CO%3B2) (pdf). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 78 (12): 27717. Bibcode:1997BAMS...78.2771T (http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1997BAMS...78.2771T). doi:10.1175/15200477(1997)078<2771:TDOENO>2.0.CO;2 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1175%2F15200477%281997%29078%3C2771%3ATDOENO%3E2.0.CO%3B2). ISSN 1520-0477 (//www.worldcat.org/issn/1520-0477). Kuenzer, C.; Zhao, D.; Scipal, K.; Sabel, D.; Naeimi, V.; Bartalis, Z.; Hasenauer, S.; Mehl, H.; Dech, S.; Waganer, W. (2009). "El Nio southern oscillation influences represented in ERS scatterometer-derived soil moisture data". Applied Geography. doi:10.1016/j.apgeog.2009.04.004 (http://dx.doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.apgeog.2009.04.004).

External links

International Research Centre on El Nio-CIIFEN (http://www.ciifen-int.org) Latest ENSO updates & predictions from the International Research Institute for Climate and Society (http://iri.columbia.edu/climate/ENSO/currentinfo/QuickLook.html) PO.DAAC's El Nio Animations (http://podaac.jpl.nasa.gov/el-nino/index.html) National Academy of Sciences El Nio/La Nia article (http://www7.nationalacademies.org/opus/elnino.html) NOAA FAQ "What is ENSO?" (http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/ensostuff/ensofaq.shtml#ENSO) Latest El Nio/La Nia Data from NASA (http://sealevel.jpl.nasa.gov/science/jason1-quick-look/) Economic Costs of El Nio / La Nia and Economic Benefits from Improved Forecasting (http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/oa/esb/?goal=climate&file=events/enso/) from "NOAA Socioeconomics" website initiative El-NioSouthern Oscillation (http://www.linkingweatherandclimate.com/ENSO/) El Nio and La Nia from the 1999 International Red Cross World Disasters Report (http://www.ericjlyman.com/elnino.html) by Eric J. Lyman. ENSO (El NioSouthern Oscillation) (http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/precip/CWlink/MJO/enso.shtml) La Nia episodes in the Tropical Pacific (http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/lanina/cold_impacts.shtml) NOAA announces 2004 El Nio (http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2004/s2317.htm) NOAA El Nio Page (http://www.elnino.noaa.gov) Ocean Motion: El Nio (http://www.oceanmotion.org/html/impact/el-nino.htm)

SOI (Southern Oscillation Index) (http://www.bom.gov.au/lam/glossary/soid.htm) The Climate of Peru (http://www.limaperunet.com/climate/climateall.html) What is El Nio? (http://www.pmel.noaa.gov/tao/elnino/el-nino-story.html) What is La Nia? (http://www.pmel.noaa.gov/tao/elnino/la-nina-story.html) El-Nino, La-Nina, Southern Oscillation, ENSO (http://biophysics.sbg.ac.at/atmo/elnino.htm) Kelvin Wave Renews El Nio - NASA, Earth Observatory image of the day, 2010, March 21 (http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/IOTD/view.php?id=43105) Animation of ENSO in Victoria, Australia (http://www.new.dpi.vic.gov.au/agriculture/environment-andcommunity/climate/understanding-weather-and-climate/climatedogs/enso) Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=El_NioSouthern_Oscillation&oldid=551033387" Categories: Tropical meteorology Physical oceanography Natural history of the Americas Natural history of Oceania Effects of global warming Climate patterns Weather hazards Spanish loanwords This page was last modified on 18 April 2013 at 20:57. Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

You might also like

- Dean Moya - SUGGESTED ANSWER (BAR 2022) LECTUREDocument97 pagesDean Moya - SUGGESTED ANSWER (BAR 2022) LECTURELuchie Castro100% (2)

- El Niño and La Niña EventsDocument7 pagesEl Niño and La Niña Eventslallu24No ratings yet

- KAREN NUÑEZ v. NORMA MOISES-PALMADocument4 pagesKAREN NUÑEZ v. NORMA MOISES-PALMARizza Angela MangallenoNo ratings yet

- El Niño and La Nina WikipediaDocument10 pagesEl Niño and La Nina WikipediaAbegail Pineda-MercadoNo ratings yet

- El Nino and La NinaDocument13 pagesEl Nino and La NinashilpaogaleNo ratings yet

- El Niño/La Niña-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO, Is A Quasi-Periodic Climate Pattern ThatDocument8 pagesEl Niño/La Niña-Southern Oscillation, or ENSO, Is A Quasi-Periodic Climate Pattern That9995246588No ratings yet

- El Niño AssignmentDocument14 pagesEl Niño AssignmentasifaqtabsaifNo ratings yet

- El Nino and La Nina: Durlov Jyoti Kalita/104Document3 pagesEl Nino and La Nina: Durlov Jyoti Kalita/104Rahul DekaNo ratings yet

- Fgfa - El Nino and La NinaDocument3 pagesFgfa - El Nino and La NinaRahul DekaNo ratings yet

- What Is El Nino?Document13 pagesWhat Is El Nino?Fernan Lee R. ManingoNo ratings yet

- El Nino Is A Weather Phenomenon Caused When Warm Water From The Western Pacific Ocean Flows EastwardDocument2 pagesEl Nino Is A Weather Phenomenon Caused When Warm Water From The Western Pacific Ocean Flows Eastwardabirami sNo ratings yet

- El NinoDocument3 pagesEl NinoCrimsondustNo ratings yet

- El Nino and La NinaDocument9 pagesEl Nino and La NinaMathew Beniga GacoNo ratings yet

- El Nino and La NinaDocument6 pagesEl Nino and La NinaEdit O Pics StatusNo ratings yet

- El - Nino - La - NinaDocument62 pagesEl - Nino - La - NinaoussheroNo ratings yet

- El Nino and La NinaDocument6 pagesEl Nino and La NinaalaxyadNo ratings yet

- 2010 Jan EnsoscillationDocument3 pages2010 Jan EnsoscillationBradee DoodeeNo ratings yet

- Ocean CurrentsDocument2 pagesOcean Currentsapi-260189186No ratings yet

- El NinoPublicDocument4 pagesEl NinoPublicJoao Carlos PolicanteNo ratings yet

- El Nino What Is El Niño?Document3 pagesEl Nino What Is El Niño?RIZKI HALWANI RAMADHAN -No ratings yet

- El NinoDocument25 pagesEl NinohimaniNo ratings yet

- The Phenomenon of El Niño and La Niña: Group: 1. 2. 3. 4Document5 pagesThe Phenomenon of El Niño and La Niña: Group: 1. 2. 3. 4Diyah FibriyaniNo ratings yet

- El Nino: By: John Vincent M. RosalesDocument8 pagesEl Nino: By: John Vincent M. RosalesJohn Mark Manalo RosalesNo ratings yet

- El Niño and La Niña (ESS Assignment)Document21 pagesEl Niño and La Niña (ESS Assignment)akshat5552No ratings yet

- ENSO ReportDocument18 pagesENSO ReportMALABIKA MONDALNo ratings yet

- Wind and Wind CirculationDocument4 pagesWind and Wind Circulationandreifernandez1412No ratings yet

- El Niño, (Spanish:: Oceanography Ocean South America Ecuador Chile Oceanic Niño Index Pacific OceanDocument2 pagesEl Niño, (Spanish:: Oceanography Ocean South America Ecuador Chile Oceanic Niño Index Pacific OceanEsteban RinconNo ratings yet

- El Nino and La NinaDocument11 pagesEl Nino and La NinaXyNo ratings yet

- El Nino & La Nina EssayDocument4 pagesEl Nino & La Nina EssayAaron Dela Cruz100% (1)

- Inter-Annual Variability Notes/Overview/Study GuideDocument3 pagesInter-Annual Variability Notes/Overview/Study GuideOliviaLimónNo ratings yet

- El Nino and La Nina Upsc Notes 27Document5 pagesEl Nino and La Nina Upsc Notes 27Mohd AshrafNo ratings yet

- How Does El Nino Affects The EnvironmentDocument4 pagesHow Does El Nino Affects The Environment방탄소년단parkchimchimwaifuNo ratings yet

- El Niño and La NiñaDocument21 pagesEl Niño and La NiñaEej EspinoNo ratings yet

- Literature Review EssayDocument12 pagesLiterature Review Essayapi-745245526No ratings yet

- El Nino La NinaDocument2 pagesEl Nino La Ninamariieya03No ratings yet

- Case Study El NinoDocument5 pagesCase Study El Ninojohn m0% (1)

- Group 2 Presentation: El NiñoDocument25 pagesGroup 2 Presentation: El NiñoFernan Lee R. ManingoNo ratings yet

- Group 2 Presentation: El NiñoDocument26 pagesGroup 2 Presentation: El NiñoFernan Lee R. ManingoNo ratings yet

- Climate Change: What Is El Niño?Document3 pagesClimate Change: What Is El Niño?Ayeah Metran EscoberNo ratings yet

- El Nino La Nina and Climate Change ModuleDocument3 pagesEl Nino La Nina and Climate Change ModuleGennelle GabrielNo ratings yet

- El Niño Term Paper For Earth Science: Submitted By: Chrisma Marie Faris BSED 1 Submitted To: Ms. Rili May OebandaDocument12 pagesEl Niño Term Paper For Earth Science: Submitted By: Chrisma Marie Faris BSED 1 Submitted To: Ms. Rili May OebandaChris MaNo ratings yet

- The Three Phases of The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)Document4 pagesThe Three Phases of The El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO)GAMMA FACULTYNo ratings yet

- CLimatology.17.El NinoDocument14 pagesCLimatology.17.El NinoVikram DasNo ratings yet

- Inquiries: The Difference Between El Niño and La Niña PhenomenaDocument8 pagesInquiries: The Difference Between El Niño and La Niña PhenomenaShirin MadrilenoNo ratings yet

- Nglish OR Cience ND EchnologyDocument14 pagesNglish OR Cience ND EchnologydeathmoonkillerNo ratings yet

- Effects of El Nino and La LinaDocument41 pagesEffects of El Nino and La LinaK Sai maheswariNo ratings yet

- La Niña EnsoDocument19 pagesLa Niña EnsoAli BabaNo ratings yet

- El Niño: Normal ConditionsDocument3 pagesEl Niño: Normal ConditionsMaria AbregoNo ratings yet

- Global Winds, Air Masses, and FrontsDocument27 pagesGlobal Winds, Air Masses, and FrontsOlga DeeNo ratings yet

- El NinoDocument2 pagesEl NinonisAfiqahNo ratings yet

- El NinoDocument2 pagesEl NinonisAfiqahNo ratings yet

- Effects On The Global Climate AnnDocument5 pagesEffects On The Global Climate AnnMaynard PascualNo ratings yet

- The Impact of El Nino and La Nina On The United Arab Emirates (UAE) RainfallDocument6 pagesThe Impact of El Nino and La Nina On The United Arab Emirates (UAE) RainfallTI Journals PublishingNo ratings yet

- El Niño and La NiñaDocument2 pagesEl Niño and La Niñacessmaria59No ratings yet

- Greenhouse EffectDocument2 pagesGreenhouse EffectGiejill SomontanNo ratings yet

- Earths ClimateDocument90 pagesEarths Climatentshehi princeNo ratings yet

- ENSO Science 222 1983aDocument7 pagesENSO Science 222 1983aJoseDapozzoNo ratings yet

- METEOROLOGY Final Research CompilationDocument31 pagesMETEOROLOGY Final Research CompilationJanmar SamongNo ratings yet

- ElninoDocument1 pageElninoWin JackpotNo ratings yet

- El Nin O and The Southern Oscillation: ObservationDocument55 pagesEl Nin O and The Southern Oscillation: ObservationAcademia GustavoNo ratings yet

- Singh and FriendsDocument2 pagesSingh and FriendsakurilNo ratings yet

- SEBI Cracks The Whip - The HinduDocument2 pagesSEBI Cracks The Whip - The HinduakurilNo ratings yet

- Alternative To MID Day Meal Scheme - SHG - VillagesDocument2 pagesAlternative To MID Day Meal Scheme - SHG - VillagesakurilNo ratings yet

- 7.decorative FinishesDocument28 pages7.decorative FinishesakurilNo ratings yet

- 3.chemical Bonding AgentsDocument14 pages3.chemical Bonding AgentsakurilNo ratings yet

- AUGUST - 2 - Amendment To RTI Act 2005Document3 pagesAUGUST - 2 - Amendment To RTI Act 2005akurilNo ratings yet

- A Glimmer of HopeDocument2 pagesA Glimmer of HopeakurilNo ratings yet

- D.R. Congo - Disputes/Conflicts - A Page From History - International Affair !Document15 pagesD.R. Congo - Disputes/Conflicts - A Page From History - International Affair !akurilNo ratings yet

- AUGUST 1 Min of Culture e AbhilekhDocument1 pageAUGUST 1 Min of Culture e AbhilekhakurilNo ratings yet

- How To Apply - Instructions To Candidates: WWW - Licindia.in/careers - HTMDocument4 pagesHow To Apply - Instructions To Candidates: WWW - Licindia.in/careers - HTMakurilNo ratings yet

- U.S.-India Economic Collaboration: Breaking NewsDocument12 pagesU.S.-India Economic Collaboration: Breaking NewsakurilNo ratings yet

- A Flangeless Complete Denture Prosthesis A Case Report April 2017 7862206681 3603082Document2 pagesA Flangeless Complete Denture Prosthesis A Case Report April 2017 7862206681 3603082wdyNo ratings yet

- Beeck V Aquaslide 'N' Dive Corp.Document2 pagesBeeck V Aquaslide 'N' Dive Corp.crlstinaaaNo ratings yet

- The Christian in Complete Armour or A Treatise On The Saint's War With The Devil William Gurnall 1655 Vol 2Document453 pagesThe Christian in Complete Armour or A Treatise On The Saint's War With The Devil William Gurnall 1655 Vol 2Spirit of William Tyndale50% (2)

- Business Continuity Planning ChecklistDocument2 pagesBusiness Continuity Planning ChecklistShawn AmeliNo ratings yet

- The Giant and The RockDocument6 pagesThe Giant and The RockVangie SalvacionNo ratings yet

- Schematic Diagram of Relay & Tcms Panel T: REV Revised by Checked by Approved byDocument1 pageSchematic Diagram of Relay & Tcms Panel T: REV Revised by Checked by Approved byTaufiq HidayatNo ratings yet

- Hematology: Mohamad H Qari, MD, FRCPADocument49 pagesHematology: Mohamad H Qari, MD, FRCPASantoz ArieNo ratings yet

- Implementing The Weil, Tate and Ate Pairings Using Sage SoftwareDocument19 pagesImplementing The Weil, Tate and Ate Pairings Using Sage SoftwareMuhammad SadnoNo ratings yet

- Kodaks Nos 1A and 3 Series IIIDocument78 pagesKodaks Nos 1A and 3 Series IIIFalcoNo ratings yet

- Quadratic Equation Solved Problems PDFDocument10 pagesQuadratic Equation Solved Problems PDFRakesh RajNo ratings yet

- Ict Grade 10Document46 pagesIct Grade 10Stephanie Shane ArellanoNo ratings yet

- Powerful Utility Tractors: Model: 2605-4R 2615-2R 2615-4R 2625-2R 2625-4R 2635-2R 2635-4RDocument2 pagesPowerful Utility Tractors: Model: 2605-4R 2615-2R 2615-4R 2625-2R 2625-4R 2635-2R 2635-4RKilluaR32No ratings yet

- 17.HB158 Welding Manual301 V30713Document38 pages17.HB158 Welding Manual301 V30713James DickinsonNo ratings yet

- About Mind Spo!s: People Also AskDocument1 pageAbout Mind Spo!s: People Also AskMichael FernandoNo ratings yet

- Alls Well That Ends WellDocument31 pagesAlls Well That Ends WellGAREN100% (2)

- English Work - Maria Isabel GrajalesDocument5 pagesEnglish Work - Maria Isabel GrajalesDavid RodriguezNo ratings yet

- PowerSCADA Expert System Integrators Manual v7.30Document260 pagesPowerSCADA Expert System Integrators Manual v7.30Hutch WoNo ratings yet

- Palm SundayDocument4 pagesPalm SundayALFREDO ELACIONNo ratings yet

- Banners of The Insurgent Army of N. Makhno 1918-1921Document10 pagesBanners of The Insurgent Army of N. Makhno 1918-1921Malcolm ArchibaldNo ratings yet

- Kerala Agricultural University: Main Campus, Vellanikkara, Thrissur - 680 656, KeralaDocument3 pagesKerala Agricultural University: Main Campus, Vellanikkara, Thrissur - 680 656, KeralaAyyoobNo ratings yet

- LS5 QTR4 - 19. LS5 - SGJ-Likas Na Yaman (Introduction)Document4 pagesLS5 QTR4 - 19. LS5 - SGJ-Likas Na Yaman (Introduction)Roy JarlegoNo ratings yet

- Rakeshkaydalwar Welcome LetterDocument3 pagesRakeshkaydalwar Welcome LetterrakeshkaydalwarNo ratings yet

- Age DiscriminationDocument2 pagesAge DiscriminationMona Karllaine CortezNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Elements in Thomas Kuhn's Historiography of ScienceDocument12 pagesPhilosophical Elements in Thomas Kuhn's Historiography of ScienceMartín IraniNo ratings yet

- Engr. Frederick B. Garcia: Proposed 3-Storey ResidenceDocument1 pageEngr. Frederick B. Garcia: Proposed 3-Storey Residencesam nacionNo ratings yet

- 03 Preliminary PagesDocument12 pages03 Preliminary PagesBillie Jan Louie JardinNo ratings yet

- Autodesk Navisworks Installation GuideDocument120 pagesAutodesk Navisworks Installation GuidemindwriterNo ratings yet

- kazan-helicopters (Russian Helicopters) 소개 2016Document33 pageskazan-helicopters (Russian Helicopters) 소개 2016Lee JihoonNo ratings yet