Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Baltimore Region Elderly Activity Patterns and Travel Characteristics Study

Baltimore Region Elderly Activity Patterns and Travel Characteristics Study

Uploaded by

Giora RozmarinCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Iowa State Patrol Fatality Reduction Enforcement Effort (FREE)Document9 pagesThe Iowa State Patrol Fatality Reduction Enforcement Effort (FREE)epraetorianNo ratings yet

- Sample Respondents of The StudyDocument2 pagesSample Respondents of The StudyMichael Qoi Laguilay40% (5)

- Annual Report 2014 Press ReleaseDocument2 pagesAnnual Report 2014 Press ReleaseAnonymous 2zbzrvNo ratings yet

- New Urbanism and TransportDocument28 pagesNew Urbanism and TransportusmanafzalarchNo ratings yet

- Getting Millennials Fromatob: The City Loop Bus Will Board at Spots #6, 7 or 8 Based On Arrival OrderDocument36 pagesGetting Millennials Fromatob: The City Loop Bus Will Board at Spots #6, 7 or 8 Based On Arrival OrderAnonymous 2zbzrvNo ratings yet

- Dangerous by DesignDocument20 pagesDangerous by DesignSAEHughesNo ratings yet

- Helmet Compliance - Condition of Habal-Habal Drivers in Metro Cebu Revised-with-cover-page-V2Document21 pagesHelmet Compliance - Condition of Habal-Habal Drivers in Metro Cebu Revised-with-cover-page-V2San TyNo ratings yet

- Level of Awareness of Selected Drivers On Traffic LawsDocument9 pagesLevel of Awareness of Selected Drivers On Traffic Lawskayeannejusto3No ratings yet

- Design Urban Transport Systems Older PopulationDocument1 pageDesign Urban Transport Systems Older PopulationSamiNo ratings yet

- Travel Mode Choice of The ElderlyDocument10 pagesTravel Mode Choice of The ElderlyShan BasnayakeNo ratings yet

- Mobility Characteristics of The Elderly and Their Associated Level of Satisfaction With Transport ServicesDocument12 pagesMobility Characteristics of The Elderly and Their Associated Level of Satisfaction With Transport ServicesShan BasnayakeNo ratings yet

- Helmet Compliance Condition of Habal HabDocument20 pagesHelmet Compliance Condition of Habal HabMikiesha SumatraNo ratings yet

- Bebe Gurl ThesisDocument33 pagesBebe Gurl Thesismalanaalter06No ratings yet

- Final Comm PlanDocument18 pagesFinal Comm PlanROZAN CHAYA MARQUEZNo ratings yet

- P299 Reynaldo - Final Research ProposalDocument12 pagesP299 Reynaldo - Final Research ProposalShamah ReynaldoNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of Motorcycle Riders in Ra 10054 Motorcycle Helmet Act of 2009Document8 pagesPerceptions of Motorcycle Riders in Ra 10054 Motorcycle Helmet Act of 2009Damianus AbunNo ratings yet

- Public Participation PlanDocument21 pagesPublic Participation PlanbethanywilcoxonNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER II TuazonDocument11 pagesCHAPTER II TuazonLester GarciaNo ratings yet

- Demand Determinants For Urban Public Transport ServicesDocument52 pagesDemand Determinants For Urban Public Transport ServicesRajesh KhadkaNo ratings yet

- Daong RevisedDocument4 pagesDaong RevisedJohn Albert De VillaNo ratings yet

- Sample Introduction Traffic Alignment ActivityDocument5 pagesSample Introduction Traffic Alignment ActivitySobaNo ratings yet

- Philippine StudiesDocument29 pagesPhilippine StudiesRic-Ric CabugNo ratings yet

- Mapping Informal Public Transport Termin PDFDocument24 pagesMapping Informal Public Transport Termin PDFemmanjabasaNo ratings yet

- Legislative Meeting Packet Feb 2012Document31 pagesLegislative Meeting Packet Feb 2012cticotskyNo ratings yet

- Dot 65841 DS1Document234 pagesDot 65841 DS1soghraNo ratings yet

- Legislative Meeting Packet Feb 2012Document31 pagesLegislative Meeting Packet Feb 2012cticotskyNo ratings yet

- Crystal City Multi Modal Transportation StudyDocument83 pagesCrystal City Multi Modal Transportation StudyCrystalCityStreetcarNo ratings yet

- 2006 - Paez Et Al - Elderly Mobility Demographic and Spatial Analysis of Trip Making in The Hamilton CMADocument33 pages2006 - Paez Et Al - Elderly Mobility Demographic and Spatial Analysis of Trip Making in The Hamilton CMARow Ordinary'sNo ratings yet

- Retail Travel Behavior Sociodemographic With Cluster AnalysisDocument21 pagesRetail Travel Behavior Sociodemographic With Cluster AnalysisrifzafakhrialNo ratings yet

- Chapter123 Research PresentationDocument27 pagesChapter123 Research PresentationApple MestNo ratings yet

- Business Policy Written Report - Traffic PolicyDocument16 pagesBusiness Policy Written Report - Traffic PolicyelaisajericagonzalesNo ratings yet

- Operational Plan - Bantay Karapatan Sa Halalan 2016Document10 pagesOperational Plan - Bantay Karapatan Sa Halalan 2016Lex Tamen CoercitorNo ratings yet

- Are We Facing Economic Gridlock - Bonnie Crombie's 'Focus On Five' E-Newsletter (May 13-27th)Document12 pagesAre We Facing Economic Gridlock - Bonnie Crombie's 'Focus On Five' E-Newsletter (May 13-27th)CrombieWard5No ratings yet

- Us - Dot - Bureau of Transportation Statistics - Freedom To Travel - EntireDocument52 pagesUs - Dot - Bureau of Transportation Statistics - Freedom To Travel - EntireprowagNo ratings yet

- Introduction!Document3 pagesIntroduction!AvinashOgiralaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Travel Characteristicsof Elders in BeijingDocument11 pagesAnalysis of Travel Characteristicsof Elders in BeijingShan BasnayakeNo ratings yet

- Impact of Covid-19 Among Public Commuters in Cotabato City Problem and Its BackgroundDocument17 pagesImpact of Covid-19 Among Public Commuters in Cotabato City Problem and Its BackgroundWalter MamadNo ratings yet

- Lessons Learned Report 1 2008Document16 pagesLessons Learned Report 1 2008Glenn RobinsonNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDocument28 pagesThe Problem and Its BackgroundKristle R BacolodNo ratings yet

- Muibi Ola CorrectedDocument88 pagesMuibi Ola CorrecteddicksonNo ratings yet

- Transit Mobile PaymentsDocument19 pagesTransit Mobile PaymentsvalenciaNo ratings yet

- Transpo Case Study (Chapter 1-5) Group 9Document28 pagesTranspo Case Study (Chapter 1-5) Group 9Macy Bautista33% (3)

- State of The Region FINAL PrintDocument60 pagesState of The Region FINAL PrintAnonymous Feglbx5No ratings yet

- 1212121Document7 pages1212121XDXDXDNo ratings yet

- CORE Excluded EnglishDocument78 pagesCORE Excluded EnglishBurma PartnershipNo ratings yet

- 3 RdtopicDocument2 pages3 RdtopicAldrei John MalanaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Travel Characteristics and Access Mode Choice of Elderly Urban Rail Riders in Denver, ColoradoDocument13 pagesAnalysis of Travel Characteristics and Access Mode Choice of Elderly Urban Rail Riders in Denver, ColoradoShan BasnayakeNo ratings yet

- Practicality - Negative SideDocument3 pagesPracticality - Negative SideMa. Theresa VillarinNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument14 pagesUntitledShaira Jane Villareal AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Kulang Kulang Thesis 1.0Document11 pagesKulang Kulang Thesis 1.0Kell LynoNo ratings yet

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument31 pagesReview of Related LiteratureRyle AquinoNo ratings yet

- Political DevolopmentDocument12 pagesPolitical DevolopmentKresha Parreñas100% (1)

- PTEG - Urban-Transport-Policies - FINAL For WebDocument60 pagesPTEG - Urban-Transport-Policies - FINAL For Webalyssa suyatNo ratings yet

- The Function of Public Transportation in Alleviating Traffic Congestion (AutoRecovered)Document4 pagesThe Function of Public Transportation in Alleviating Traffic Congestion (AutoRecovered)krizziahannekilapioNo ratings yet

- City Council 20240403 PacketDocument3 pagesCity Council 20240403 PacketIndiana Public Media NewsNo ratings yet

- Transportation for the Elderly: Changing Lifestyles, Changing NeedsFrom EverandTransportation for the Elderly: Changing Lifestyles, Changing NeedsNo ratings yet

- Governing the Fragmented Metropolis: Planning for Regional SustainabilityFrom EverandGoverning the Fragmented Metropolis: Planning for Regional SustainabilityNo ratings yet

- Leading the localities: Executive mayors in English local governanceFrom EverandLeading the localities: Executive mayors in English local governanceNo ratings yet

- Gridlock: Why We're Stuck in Traffic and What To Do About ItFrom EverandGridlock: Why We're Stuck in Traffic and What To Do About ItRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- USCSDocument1 pageUSCSLamija AhmetspahićNo ratings yet

- Wavin PVC Pressure Pipe Systems Product and Technical Guide: Intelligent Solutions ForDocument1 pageWavin PVC Pressure Pipe Systems Product and Technical Guide: Intelligent Solutions ForGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Approved Cross Sections 3Document1 pageApproved Cross Sections 3Giora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Paper No. 01-2601: Leedoseu@pilot - Msu.eduDocument26 pagesPaper No. 01-2601: Leedoseu@pilot - Msu.eduGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- KEMBLA CatalogueDocument13 pagesKEMBLA CatalogueGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Soil - FillingDocument6 pagesSoil - FillingGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Construction and Performance of Ultra-Thin Bonded Hma Wearing CourseDocument26 pagesConstruction and Performance of Ultra-Thin Bonded Hma Wearing CourseGiora Rozmarin100% (1)

- Development of Critical Field Permeability and Pavement Density Values For Coarse-Graded Superpave PavementsDocument30 pagesDevelopment of Critical Field Permeability and Pavement Density Values For Coarse-Graded Superpave PavementsGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Constitutive Modeling of The Flexural Fatigue Performance of Fiber Reinforced and Lightweight ConcretesDocument18 pagesConstitutive Modeling of The Flexural Fatigue Performance of Fiber Reinforced and Lightweight ConcretesGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Paper No. TRB #01-3486 Development of Testing Procedures To Determine The Water-Cement Ratio of Hardened Portland Cement Concrete Using Semi-Automated Image Analysis TechniquesDocument14 pagesPaper No. TRB #01-3486 Development of Testing Procedures To Determine The Water-Cement Ratio of Hardened Portland Cement Concrete Using Semi-Automated Image Analysis TechniquesGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- A Consultant's Perspective of Highway Network Asset Management Practice in EnglandDocument8 pagesA Consultant's Perspective of Highway Network Asset Management Practice in EnglandGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Niittymaki@hut - Fi: Development of Integrated Air Pollution Modelling Systems For Urban Planning-DIANA ProjectDocument18 pagesNiittymaki@hut - Fi: Development of Integrated Air Pollution Modelling Systems For Urban Planning-DIANA ProjectGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Congestion Pricing and Roadspace Rationing: An Application To The San Francisco Bay Bridge CorridorDocument18 pagesCongestion Pricing and Roadspace Rationing: An Application To The San Francisco Bay Bridge CorridorGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- TRB ID: 01-3271: Polydor@Document17 pagesTRB ID: 01-3271: Polydor@Giora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- 00149Document21 pages00149Giora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- AC A S T Gis D: Learinghouse Pproach To Haring Ransportation ATADocument16 pagesAC A S T Gis D: Learinghouse Pproach To Haring Ransportation ATAGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Paper No. 01-2558: Title: Commuter Rail Station Governance and Parking PracticesDocument20 pagesPaper No. 01-2558: Title: Commuter Rail Station Governance and Parking PracticesGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Comparative Evaluation of Field Performance of Pavement Marking Products On Alternative Test Deck DesignsDocument23 pagesComparative Evaluation of Field Performance of Pavement Marking Products On Alternative Test Deck DesignsGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Commuter Activity Scheduling and Sequencing Behavior Across Geographical ContextsDocument28 pagesA Comparison of Commuter Activity Scheduling and Sequencing Behavior Across Geographical ContextsGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Concrete Slab Track State of The Practice: TRB Paper No. 01-0240Document32 pagesConcrete Slab Track State of The Practice: TRB Paper No. 01-0240Giora Rozmarin0% (1)

- Passing ReportDocument1 pagePassing Reportmht1No ratings yet

- Century Class ST and Coronado Driver's ManualDocument239 pagesCentury Class ST and Coronado Driver's ManualJohn AdamsNo ratings yet

- AOADocument7 pagesAOANitin SaxenaNo ratings yet

- VeloCity2011 Presentation Cycling AlbaniaDocument31 pagesVeloCity2011 Presentation Cycling AlbaniaDorina PojaniNo ratings yet

- SIDRA INTERSECTION - MODEL FUNDAMENTALS WORKSHOP Contents - 2019Document3 pagesSIDRA INTERSECTION - MODEL FUNDAMENTALS WORKSHOP Contents - 2019Marcelo QuintanilhaNo ratings yet

- Fuel Issues Form: م ش ش تامدخلاو تايرفحلل ةينطولا ةكرشلا National Drilling & Services Co. L.L.CDocument1 pageFuel Issues Form: م ش ش تامدخلاو تايرفحلل ةينطولا ةكرشلا National Drilling & Services Co. L.L.Ccmrig74No ratings yet

- LOTboarding PassDocument2 pagesLOTboarding PassbisonshotNo ratings yet

- Ahemdabad Case StudyDocument41 pagesAhemdabad Case StudyAr Kajal GangilNo ratings yet

- MB/L No - DMM209522 B/L No. 301-19-44854-301457: Combined Transport Bill of LadingDocument6 pagesMB/L No - DMM209522 B/L No. 301-19-44854-301457: Combined Transport Bill of LadingsravanNo ratings yet

- SCHOOL BASED ASSIGNMENT Geo (SJW)Document26 pagesSCHOOL BASED ASSIGNMENT Geo (SJW)Drippy PacNo ratings yet

- Tourism and CultureDocument5 pagesTourism and CultureLouise Marithe FlorNo ratings yet

- 6E 2134 1015 Hrs Zone 2 17F: Boarding Pass (Web Check In)Document2 pages6E 2134 1015 Hrs Zone 2 17F: Boarding Pass (Web Check In)alondraortega07No ratings yet

- JamshedpurDocument12 pagesJamshedpurविशालविजयपाटणकरNo ratings yet

- Airline Production PlanningDocument13 pagesAirline Production PlanningFadhlurrohman AziziNo ratings yet

- Place Making As An Approach To Revitalize Neglected Urban Open SpacesDocument10 pagesPlace Making As An Approach To Revitalize Neglected Urban Open SpacesSandra SamirNo ratings yet

- Stand-On Stacker Ergo Ajn 160Sdtfv: Mast Type Lift Height H Height of Mast Lowered h1 Max Mast Height h4Document2 pagesStand-On Stacker Ergo Ajn 160Sdtfv: Mast Type Lift Height H Height of Mast Lowered h1 Max Mast Height h4Xb ZNo ratings yet

- Incorporating Online Home Delivery ServicesDocument2 pagesIncorporating Online Home Delivery ServicesSead RizvanovićNo ratings yet

- Highway: Geometric DesignDocument33 pagesHighway: Geometric DesignGabriel Abanto QueseaNo ratings yet

- Completed Report Dissatisfaction 7-20-2023 1-48-08 PMDocument3 pagesCompleted Report Dissatisfaction 7-20-2023 1-48-08 PMCs ServiceNo ratings yet

- SAFMC Logbook: By: Nicole, Rui Yao and Guang YuanDocument17 pagesSAFMC Logbook: By: Nicole, Rui Yao and Guang YuansimpNo ratings yet

- R AFPam 10-1403 Air Mobility Planning Factors PDFDocument27 pagesR AFPam 10-1403 Air Mobility Planning Factors PDFStephen SmithNo ratings yet

- Business - Traveller.uk June.2023Document78 pagesBusiness - Traveller.uk June.2023Daniel dAzNo ratings yet

- Sample Vesselsearch Table f3I3yayz6TDocument4 pagesSample Vesselsearch Table f3I3yayz6TLuis Enrique RomeroNo ratings yet

- Regenerative Braking in Trains MinorDocument25 pagesRegenerative Braking in Trains Minormanish guptaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Road Damages in The Flow of Traffic in Iloilo CityDocument18 pagesThe Effect of Road Damages in The Flow of Traffic in Iloilo CityJudy ann RodriguezNo ratings yet

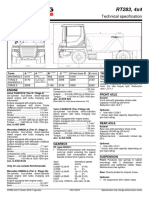

- Terberg RT283 PDFDocument2 pagesTerberg RT283 PDFHemerson FurtadoNo ratings yet

- Accident Analysis and Prevention: Thomas Kerwin, Brad J. Bushman TDocument7 pagesAccident Analysis and Prevention: Thomas Kerwin, Brad J. Bushman TJuan Pablo GMNo ratings yet

- Mec 531 Project Title Sept2013-Jan2014Document3 pagesMec 531 Project Title Sept2013-Jan2014arina azharyNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Seat ReservoirDocument1 pageDynamic Seat Reservoirmr.sithulwin22No ratings yet

- JRC Pipe RecoveryDocument16 pagesJRC Pipe RecoveryJean CarloNo ratings yet

Baltimore Region Elderly Activity Patterns and Travel Characteristics Study

Baltimore Region Elderly Activity Patterns and Travel Characteristics Study

Uploaded by

Giora RozmarinOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Baltimore Region Elderly Activity Patterns and Travel Characteristics Study

Baltimore Region Elderly Activity Patterns and Travel Characteristics Study

Uploaded by

Giora RozmarinCopyright:

Available Formats

TRB Paper Number 01-0544

Baltimore Region Elderly Activity Patterns and Travel Characteristics Study

By

Earl Long Baltimore Metropolitan Council 2700 Lighthouse Point East, Suite 310 Baltimore, MD 21224-4774 Telephone: 410-732-0500, X 1037 FAX: 410-732-8248 e-mail: elong@baltometro.org

John Morrison Ketron Division of the Bionetics Corporation 650 Beacon Street Boston, MA 02215 Telephone: 617-421-9005 FAX: 617-421-9161 e-mail: ketron@tiac.net John Balog Ketron Division of the Bionetics Corporation 103 Arrandale Boulevard Exton, PA 19341 Telephone: 610-280-9002 FAX: 610-280-9079 e-mail: jbalog@ketron.com

Abstract File Name: 01-0544.ab Paper File Name: 01-0544.doc Number of Words: 6,718 + 0 figures

Long, Morrison, Balog

Baltimore Region Elderly Activity Patterns and Travel Characteristics Study

STUDY CONTEXT

The Baltimore region is a major metropolitan area in the State of Maryland near the southern end of the urban Northeast Corridor. The region is bounded on the east by the Chesapeake Bay and the Maryland Eastern Shore, on the west by the Washington region, and on the north by the State of Pennsylvania. The 2,253 square mile Baltimore region is made up of six major political jurisdictions Baltimore City and the five suburban counties of Anne Arundel, Baltimore, Carroll, Harford, and Howard. The City of Annapolis is also included in the region. Baltimore City, the central city of the region, covers about 4 percent of the total regional land area while the five suburban jurisdictions occupy the other 96 percent. The current population of the Baltimore region is just over 2.5 million. Twenty-seven percent of the population of the region live in the central city, and 73% live in the suburban jurisdictions. Major travel corridors in the region are served by fixed route bus service, Light Rail, Metro subway, and MARC commuter rail. Paratransit services are available throughout much of the region.

PLANNING IN BALTIMORE REGION

The Baltimore Metropolitan Council (BMC) is a private non-profit regional planning agency that is committed to identifying regional interests and developing collaborative strategies to improve the quality of life and economic vitality of the region. The Transportation Steering Committee (TSC) is the federally-mandated Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) for the Baltimore region. The TSC consists of designated representatives appointed by the chief elected officials of the above-named jurisdictions, and designated representatives from the Maryland Department of Transportation, the Maryland Department of the Environment, and the Maryland Department of Planning. The TSC is responsible for developing and approving the regional Long Range Transportation Plan, the Transportation Improvement Program, and directing the Unified Planning Work Program (UPWP). The Baltimore Region Elderly Activity Patterns and Travel Characteristics Study (Elderly Travel Study) was part of the 1998 UPWP adopted by the TSC. The BMC has a Transportation Planning Division which is responsible for administering and carrying out the work of the UPWP, which included the Elderly Travel Study. The BMC staff was responsible for coordinating and guiding the work of the consultant for this study, and

Long, Morrison, Balog assisting the consultant in maintaining the necessary liaison with affected public agencies and organizations throughout the study.

STUDY BACKGROUND

The Baltimore region, like other metropolitan regions in the United States, is experiencing a long-term population aging trend. This ongoing trend is expected to intensify as the Baby Boom population begins to reach retirement age in the year 2010, and will last until around 2050 when the last of the Baby Boom population ages its way out of the life cycle. The dynamics of the elderly population growth in the Baltimore region mirror major national aging trends. According to the 1980 Census, there were more seniors living in the suburban portion of the Baltimore region than in the central city. This was the first time in history this demographic phenomenon has occurred both in the Baltimore region and nationally. The 1990 Census confirmed that the region was continuing to experience elderly population shifts from the central city to suburban jurisdictions as well as the further aging of the overall population. The combined effects of these aging-related trends are expected to be intensified by the ongoing phenomenon of in-place retirement. Meeting growing elderly activity, travel, and human service needs in the Baltimore region is expected to require substantially greater commitments from both the public and private sectors during the coming decades.

STUDY JUSTIFICATION

Work on the now completed 1998 Baltimore Regional Transportation Plan (BRTP) found that one of the most significant demographic changes that will occur in the Baltimore region during the time period covered by the BRTP (through the year 2020) will be the continued growth of the regions elderly population. By 2020, the elderly will make up approximately 17 percent of the entire regional population, and an even higher percentage (20%+) of the regions driving age population. Much of the anticipated growth of the elderly in the Baltimore region will be concentrated in low density suburban areas. By the year 2020, almost 80 percent of the regions elderly population will live in suburban jurisdictions. If in-place retirement trends persist, over 90% of the regions elderly population will continue to live in the same jurisdictions in which they originally retired. The trends analysis which was used to develop the BRTP was based on detailed knowledge of the activity patterns and travel characteristics of the regions prime driving age population (ages 16-64). In conjunction with the development of the BRTP, an extensive literature review found that significant information was available on elderly human factors characteristics, national-level elderly travel studies, and human service transportation programs that provide mobility options for the elderly and individuals with disabilities. However, very little information was found concerning the activity patterns and travel characteristics of the elderly in the Baltimore region.

Long, Morrison, Balog

STUDY GOALS

To overcome this critical lack of information on which to base future transportation planning for seniors in the region, the TSC authorized and funded this study to quantitatively define elderly activity patterns and travel characteristics in the Baltimore region. BMC structured the study to achieve the following goals: To provide a quantitative basis for understanding the relationships between elderly activity patterns, independent elderly mobility, and alternative elderly mobility options in the Baltimore region. To help to identify what public actions may be necessary to extend safe, independent elderly mobility, and to provide more user-friendly alternative transportation services to the elderly with mobility impairments, and to individuals with disabilities. To determine if information from national-level elderly travel studies could be adapted to Baltimore region transportation planning applications.

STUDY TEAM

Based on responses to a Request For Proposals (RFP), a BMC consultant selection committee chose the Ketron Division of the Bionetics Corporation (Ketron) to conduct the Elderly Travel Study. The consultant team included two sub-consultants to assist in the conduct of the study. The Schaefer Center for Public Policy (Schaefer Center), a public opinion research organization in Baltimore, assisted in the conduct of the telephone surveys and travel diaries, and the Family Research Group (FRG) of Baltimore provided the facilities and conducted the elderly travel focus group.

STUDY METHODOLOGY

During the Spring of 1999, Ketron conducted the Elderly Travel Study for the BMC. This was one of the first regional studies to document both central city and suburban elderly travel characteristics. BMC required that the Elderly Travel Study provide quantitative estimates of elderly activity patterns and travel characteristics in the Baltimore region within acceptable levels of reliability and margin of error. The study methodology designed by Ketron consisted of three phases: 1) telephone surveys, 2) one-day travel diaries, and 3) a focus group. The actual study surveying activities extended over a two month period from mid-April through mid-June 1999. Prior to and during this time period, there were no events or conditions that could have influenced the findings of the surveys, travel diaries, or focus group.

Long, Morrison, Balog Telephone Surveys Part 1 of the study consisted of telephone surveys. The purpose of the telephone survey was to measure self-reported travel frequencies, travel modes utilized, and travel problems experienced by senior respondents and all seniors living in respondent households. The telephone survey was designed for Computer Aided Telephone Interviewing (CATI). The survey questions were organized into 15 functional segments. The Schaefer Center conducted the telephone surveys. Potential senior respondents for this study were selected as a stratified random sample of all seniors in the six jurisdiction Baltimore region. A list of 6,000 Baltimore region seniors selected at random from a database of approximately 96,000 Baltimore region seniors was purchased from American Consumer Lists. The criteria for the initial selection of 6,000 candidates was that all potential respondents were to be 65 years or older, and be selected in proportion to the number of seniors living in each of the Baltimore region jurisdictions. The list of 6,000 seniors also contained demographic data about the potential respondents including age, length at current domicile, housing type, and income category.

From the address file of potential respondents, the home locations of the 6,000 candidates were geocoded and their home census block groups were determined. Residents were geocoded so that a final stratified sample of survey candidates could be drawn that was representative of the residential density of Baltimore region seniors. Using 1990 census data, Ketron rank ordered all census block groups in the six jurisdiction region. The ranking ran from the block group containing the largest number of seniors to the block group containing the smallest number of seniors. These block groups were then subdivided into four quartiles such that each quartile contained approximately the same total number of seniors. Randomly selected block groups were then selected from each quartile sufficient to provide 1,200 potential respondents representative of all elderly densities throughout the region. A surveying goal was then established for each selected block group. This segmentation plan was designed to assure that the completed survey would be representative of the population distribution of seniors in the Baltimore region. The initial goal of the study was to complete 200 telephone surveys and to record as many travel diaries as possible. As the survey progressed, it became clear that the completion rate of the surveying was higher than anticipated and the surveying goal could be increased. The surveying goal was accordingly increased to 300 completed telephone surveys and a second random selection of block groups segmented by jurisdiction and quartile was drawn. However, in the second selection, Ketron did not select any block groups from Baltimore City. This decision was made to increase the proportion of suburban elderly in the sample, reflecting the growing need for governments to prepare for the travel and other needs of seniors retiring in their suburban home locations. The telephone survey portion of the study was concluded with 308 completed surveys. The duration of each survey was a function of the number of seniors living in the respondent household. The total CATI survey contained over 100 questions to cover households with a single and multiple seniors. Most surveys of single-senior households required 50 to 60

Long, Morrison, Balog minutes to complete. Two-senior households required 70 to 80 minutes. Three and four senior households required from 90 to 105 minutes. Anecdotal information prior to the survey indicated that senior telephone surveys should be short, probably not longer than 15 to 20 minutes. However, it was clear from the 1995 National Personal Transportation Study (1995 NPTS) and Ketrons survey experience that longer-duration telephone interviews could be successfully completed by seniors. To obtain the maximum amount of information from the telephone interviews, a well designed, long-duration telephone survey was developed that made allowances for possible respondent fatigue. Several break points were included in the survey where seniors could conclude the interview and provide useful information short of actually completing the full telephone survey.

It is a significant that none of the seniors who agreed to be surveyed aborted the telephone interview at any of the interim break points. The study confirmed that longer-duration telephone surveys can be successfully completed if they are well designed, presented by experienced professional interviewers, directly recorded in a computer database, and relevant to the target population. Travel Diaries Part 2 of the study consisted of one-day travel diaries. Ketron developed the travel diary questions. Each senior who completed a telephone survey was asked to keep a one-day travel diary. The prospective travel day was assigned to each respondent during the telephone survey, and the travel diary was mailed out within two days after each telephone survey. The computer assigned the travel day to be 8 or 9 days later than the day of the telephone survey. The respondents agreed to maintain a travel diary, and agreed to read the travel diary to a Schaefer Center surveyor when the surveyor called back approximately two days after the travel day. The travel diary which consisted of 13 pages was mailed to each respondent. For ease of reading, the diary was printed in 14 point Arial bold font throughout. The first page identified the respondent and provided instructions for recording trips. The 2nd through 13th pages were for registering the First Trip, Second Trip, etc. Thus, the diary could record up to 12 trips and provided seven pieces of information about each trip. The trip descriptors record the same information as those captured in the 1995 NPTS. As was the case with the travel diaries in the 1995 NPTS, the actual completion rate of the diaries by seniors was approximately 50%. Eighty-six travel diaries had been recorded by May 11, the final day of telephone surveys. Recording of the travel diaries continued for another week, and was concluded on May 19. In addition to the 133 seniors who recorded their trips and read back trip information to interviewers, an additional 25 respondents reported to the interviewers that they had taken no trips on their trip day. Thus, a total of 158 travel diaries were recorded as completed.

Long, Morrison, Balog Focus Group

Part 3 of the study consisted of a focus group of seniors who participated in the telephone survey. During the telephone survey phase, persons who completed the telephone survey were asked whether they would be willing to participate in a follow-up focus group to further discuss senior travel issues. Ninety-six individuals indicated a willingness to participate in a follow-up group. Ketron provided FRG with participant contact information. FRG contacted all of the candidates and confirmed 12 senior participants for the focus group. Confirmation calls were made on the day of the focus group, and 4 of the 12 seniors canceled. Additionally, 1 of the remaining 8 seniors failed to arrive for the focus group. The follow-up focus group was attended by seven seniors who participated in the telephone surveys. All participants in the focus group were active travelers who are in the Low Travel Need category. They were chiefly concerned about how failing eyesight and reflexes were affecting their driving ability. Four of the participants also were public transportation patrons. Their concerns were for enhanced transit services and for mitigation of crime and safety issues. The focus group was conducted on the afternoon of June 17, 1999 at the FRG focus group center located in downtown Baltimore. The date was selected because there was no home baseball game or other special event which would have caused significant traffic complications for focus group participants. No respondents from Carroll, Harford, or Howard Counties agreed to participate in the focus group. The seven respondents who participated in the focus group, however, were an adequate representation of active travelers in the senior population. The focus group discussion guide, which was developed by Ketron in conjunction with FRG, was used by the moderator to coordinate the discussion. The focus group discussion took two hours to complete. Respondents appeared to be greatly pleased to have this opportunity to express their opinions and concerns about travel around the Baltimore region.

STUDY STATISTICAL ACCURACY

Ketrons segmentation plan was designed to produce a stratified sample of respondents that was proportional to the senior population of each jurisdiction, and within jurisdictions, proportional to the population density of seniors in block groups. Seniors in Baltimore and Carroll Counties declined to be surveyed at a higher rate than seniors in the other four jurisdictions. To adjust for these differential survey rates, Ketron made a decision to include a higher proportion of seniors from Baltimore County and other suburban jurisdictions in the group of prospective respondents. By increasing the number of suburban respondents, the tendency of Baltimore County and Carroll County seniors who declined to be surveyed was counteracted.

Long, Morrison, Balog This study has a margin of error of +/-5% to 7% at the 90% confidence level for Baltimore County, and for the other four suburban jurisdictions when their 124 respondents are aggregated. Given its smaller sample size, data from the 74 respondents in Baltimore City has a reliability of +/- 8%. Extensive analysis was conducted to determine whether the cohort of seniors surveyed matched the geographic distribution of seniors in the Baltimore region, and whether the demographics of the senior cohort surveyed influenced the response pattern. The following is a summary of the findings regarding the patterns of completed and refused surveys: The pattern of completed surveys adequately matches the percentage distribution of seniors expected in the 2000 census by jurisdiction, and also matches the population density of seniors by census tract.

Apartment dwellers as a rule were less willing to be surveyed than homeowners. Homeowners in Baltimore County were less willing to be surveyed than homeowners in the other five jurisdictions. Apartment dwellers across all jurisdictions were equally reluctant to be surveyed. Seniors of lower income and seniors of higher income were more reluctant to be surveyed than were middle-income seniors. Younger seniors and older seniors were more reluctant to be surveyed than were seniors in the 71-75 age bracket. Length of residence had no impact on the willingness of seniors to be surveyed.

On the basis of the rate of growth in the senior population, the six jurisdictions were segmented into three groups. The first group includes Baltimore County which has the highest percentage rate of growth in senior population. The second group includes Anne Arundel, Carroll, Harford, and Howard Counties which are experiencing moderate growth in senior population. The third group includes Baltimore City which is experiencing negative growth in senior population. Based on the above observations, the overall statistical findings in this study can be assumed to have a margin of error of +/-5% to 7% at a 90% confidence level. However, due to the demographic impacts seen in the willingness to be surveyed findings, estimates may underrepresent the actual level of travel characteristics and travel need experienced by apartment dwellers and lower-income residents in the six jurisdiction region. Likewise, travel characteristics and travel need estimates may under-represent the actual experiences of younger seniors and the oldest seniors. Finally, to a lesser extent, these estimates may under-represent the actual travel characteristics and travel needs of homeowners in Baltimore County, and by upper income residents throughout the region.

Long, Morrison, Balog

MAJOR STUDY FINDINGS

Level of Travel Need The most significant finding of this study was the documentation of three levels of travel need among the current cohort of seniors in the Baltimore region. These travel need measures were derived from extensive statistical analysis of responses to the telephone interviews and supporting data from the travel diaries. From this analysis, composite measures of travel need were developed which related travel frequency patterns, travel characteristics, travel-related disabilities, and level of travel frequency satisfaction and life satisfaction. Through use of multiple regression analysis, it was determined that only four of the questions asked of respondents had predictive value for explaining self-reported travel frequency. These variables are: 1) ability to walk 3 blocks unassisted; 2) difficulty going shopping; 3) whether the senior drives, and 4) gender of the respondent. Of the four predictive variables, the respondents ability to walk 3 blocks unassisted proved to be the most robust in explaining travel frequencies reported in this study. From the cluster analysis, the pattern that emerged is one of reinforcing disabilities, or offsetting disabilities. The High Travel Need category is composed of seniors who have reinforcing disabilities, that is, seniors who cannot walk and also cannot drive. The Moderate Travel Need category is composed of seniors who have offsetting disabilities, that is, seniors who cannot walk but do drive, or seniors who can walk but do not drive. The Low Travel Need category is composed of seniors who can walk, drive, and have no difficulty going shopping or to the doctor. The final estimates of travel need developed in this study are as follows: High Travel Need Approximately 7% to 8% of the senior population in all of the jurisdictions in the Baltimore region are in the High Travel Need category, characterized as traveling out of their homes infrequently, having a moderate to severe disability, and reliant on family and friends for both long and short-distance travel. The proportion of seniors in the High Travel Need category was found to be greater in the 80+ group. Moderate Travel Need Approximately 13% of the senior population of the suburban jurisdictions and approximately 26% of the senior population of Baltimore City are in the Moderate Travel Need category, characterized by moderately frequent travel, reliance on family and friends for longer-distance (but not short-distance travel), mild physical disabilities and no drivers license or reduced driving.

Long, Morrison, Balog Low Travel Need Approximately 79% of the senior population of the suburban jurisdictions and approximately 65% of the senior population of Baltimore City are in the Low Travel Need category, characterized by frequent travel out of their homes, no reliance on friends or family, and no or insignificant physical disabilities. These estimates of travel need should assist organizations, agencies, and business interests in the Baltimore region to scope the magnitude of senior travel demand at different travel need levels. In-Place Retirement Another significant finding of this study was documentation of the level of in-place retirement in the Baltimore region. The level of in-place retirement is extremely important because it is a direct measure of the long-term spatial distribution of the senior population throughout the region, and the duration of travel-related difficulties that seniors may experience as a result of their residential location.

This study verified that national-level movers-by-age survey data from the 1986 and 1996 Geographic Mobility Survey by the U. S. Census Bureau is applicable to the Baltimore region. Both Census surveys showed that substantially less than 10% of seniors (age 65+) move. Of those seniors that move, approximately 3% move locally, and approximately 2% move elsewhere (beyond the region where they previously lived). During the telephone interview, respondents were asked whether they plan to continue living at their present address for the foreseeable future, or do they plan to move in the foreseeable future. Ninety (90) percent of the respondents stated that they plan to remain in their current residence for the foreseeable future, 6.6% plan to move in the near future or in a few years, and 2.0% plan to remain as long as they can be independent. Further analysis documented that there is a minimal propensity of Baltimore region PreBaby Boom seniors to move by travel need category, age of respondent, or jurisdiction of residence. From this analysis, it is clear that the social responsibility of jurisdictions in the Baltimore region to address the travel and other needs of older residents will not be mitigated by relocation of seniors out of their current residences. Travel Characteristics Trip Purposes From the responses to the telephone survey and travel diaries, 17 different senior trip purposes were identified. These trip purposes were aggregated into 5 functionally-related trip purpose groups as follows:

Long, Morrison, Balog

10

Socialization-Related Trips Approximately 30% of total senior trips fall into this category, which includes trips in the following subgroups: Visiting Friends Family (8%), Dining Out (7%), Religious Activity (7%), Other Social Recreation (4%), School (2%), and Senior Center (2%). Shopping-Related Trips Approximately 27% of total senior trips falls into this category, which includes trips in the following subgroups: Shopping (25%), and Convenience Store (2%). Miscellaneous Trips Approximately 20% of senior trips fall into this category, which includes trips in the following subgroups: Other (18%), Vacation (1%), Picking up and Dropping Off Passengers (1%). Life Maintenance-Related Trips Approximately 16% of senior trips fall into this category, which includes trips in the following subgroups: Personal Business (9%) and Medical (7%). Employment-Related Trips Approximately 7% of senior trips fall into this category, which includes Work (5%) and Work-related (2%). These trips are not distributed uniformly throughout the week which indicates that senior employment may tend to be part-time in nature. Of the total trips made by seniors, 72% occur on weekdays, and 28% on weekends. Travel Modes From the travel diary responses, the following are the major findings regarding travel modes used by seniors in the region: Seniors who travel out of their homes daily or several times a week utilize a variety of travel modes to get around. However, seniors who travel infrequently, that is, once a week or less, are almost exclusively dependent on family and friends for transportation. Even for infrequent senior travelers, the ability to walk determines travel frequency. Those who are able to walk 3 blocks, even with difficulty, are able to get out of their homes at least a few times a week. Those who are unable to walk 3 blocks unassisted leave their homes on average only a few times per month. Age, jurisdiction of residence, family composition, and employment characteristics had no significant influence on the travel mode utilized by seniors. The travel modes used by seniors in the region are as follows: Drive Alone Auto Approximately 58% of senior trips are made by drive alone auto. Shared Ride Auto Approximately 34% of senior trips are made using rideshare arrangements, provided by family, friends, relatives (21%), and others (13%).

Long, Morrison, Balog

11

Non-Motorized Modes Approximately 5% of senior trips are made by walking, wheeling, and biking. Transit / Paratransit Modes Approximately 1% of senior trips are made using transit and paratransit.

It is evident that seniors in the region are committed to travel by automobile. Over 90% of all senior trips are made by automobile as drivers (58%) or as shared ride passengers (34%). The dispersed travel patterns of the Pre-Baby Boom seniors surveyed in this study do not appear to be conveniently served by existing fixed public transit routes. Many seniors regard paratransit service as time consuming and unreliable especially for return trips. The responses of seniors in this survey clearly indicates that the current cohort of seniors in the region are not transit and paratransit dependent. Travel by Day From the travel diary responses, senior trips in the region increase Monday through Wednesday, then decline through Sunday. Maximum senior trips occur on Wednesday (4.7 trips/senior). Minimum senior trips occur on Sunday (2.9 trips/senior). The average daily trips taken by seniors is 3.5 trips/senior. Trip Lengths From the travel diary responses, senior trips in the region require travel of 1 to 6 miles or more regardless of purpose. Approximately 93% of all trips recorded by seniors are beyond walking distance and require motorized travel. Only 7% of senior trips have a distance of 3 blocks or less. And of those, only 1% of trips are within the same building and 2% are trips on the same block. The average senior trip length in the region is approximately 5.7 miles.

MAJOR FOCUS GROUP THEMES

A focus group was held after the completion of the surveying phases of the study. Four of the focus group participants were users of public transportation, and six participants in the focus group held current drivers licenses. One participant had never learned to drive. She was the most active public transportation user in the focus group. All of the seven focus group participants were in the Low Travel Need category; all reported that they travel every day, and several had used public transportation to reach the focus group session. A review of the responses of focus group participants to telephone survey questions about impediments to local and regional travel revealed concerns about lack of good public transportation and safety/security for senior citizens.

Long, Morrison, Balog Driving Issues

12

The facilitator initiated a discussion of modes of travel, who helps the respondents, and challenges to driving. Some of the respondents stated that they enjoy driving and stated that they feel happy driving. As a secondary travel mode, people preferred the Metro subway and Light Rail. There was an active discussion about older driver problems. Participants agreed that they had curtailed night driving and driving when it was raining. Seniors do not make long driving trips alone. Two participants still drive at night, but both try to avoid rush hour. All participants indicated that they tried to avoid rush hour. All agreed that vision was an issue and, surprisingly, all respondents agreed that senior drivers should have annual vision examinations. One respondent stated that she goes to her eye-doctor voluntarily for eye examinations. One respondent stated that judgement when driving was becoming a problem. Another mentioned that she used to reflexively check for children while she was driving, but now has to remember to do that. Others mentioned that younger drivers are more aggressive and the reflexes of seniors were less quick and that their response times were longer. Participants were concerned about the readability of signs, especially the white-on-green street signs which they regard as difficult to read at night. Participants agreed that there should be a driver license and vision checks each year for seniors. Public Transportation Issues The facilitator led a discussion about the use of public transportation. Participants talked about problems they experience using transit. They felt that ignorance of public transit options and the time it takes to travel on public transportation combined to reduce utilization. Several participants stated that they receive incorrect and incomplete directions on how to use public transportation. Other stated that they were always put on hold when they called the customer service center for transit information and directions. Participants discussed safety and public transportation. Some of the concerns expressed by participants included: lack of understanding about transit fare structure, fare equipment and transit routes, irregular transit service and long headways especially during off-peak periods, fear of missing connections and being stranded in unfamiliar surroundings, apprehension about strangers around transit stops, concern about unruly passengers and school students on transit vehicles, apprehension about being isolated on multi-car trains, and concern about broken elevators and escalators at stations. Participants also pointed out the difficulties carrying packages on public transportation, long walking distances to and from transit stops, and lack of evening and Sunday service. As a wrap-up, the moderator asked participants to list things that should be done to improve public transportation. The following is the list of recommendations suggested by focus group participants:

Long, Morrison, Balog 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. Improve transit security. Improve station escalators and elevators maintenance. Improve transit information services. Provide more frequent transit service, particularly on weekends. Provide more Park-Ride lots and bus service in the suburbs. Provide volunteers at senior centers to help seniors learn to use transit.

13

Paratransit and Individualized Service Issues In closing, participants were asked about paratransit services. None of the participants were registered paratransit riders, but one participant rides with her husband. Most participants knew other seniors who are paratransit riders. The general consensus is that the service runs late and is not dependable, especially on return trips. There was not a lot of enthusiasm for paratransit service among the participants. There was somewhat more enthusiasm for other models of individualized services, including shuttles to shopping malls and neighborhood connector services. Participants stated that some seniors might benefit from these services, but were pessimistic about how long such services might last. Further discussion of paratransit options could not be generated.

TRANSPORTATION IMPROVEMENTS RECOMMENDED BY SENIORS

During the telephone surveys, respondents were asked to name impediments that posed the biggest problem for them in getting around their neighborhood and around the region. After each of the problem questions, respondents were asked to identify improvements that would enhance their mobility in the neighborhood and the region. For each question, they were allowed to identify up to four problems or four improvements. The responses to the travel problem and travel improvement questions were analyzed and grouped into the three travel need categories defined in this study. This grouping of responses showed that there was excellent conceptual agreement between the travel need categories and problems/improvements identified by respondents in those categories. Recommendations by High Travel Need Respondents - Seniors in the High Travel Need category expressed a desire for better paratransit service and improve safety for both local and regional travel. Recommendations by Moderate Travel Need Respondents - Seniors in the Moderate Travel Need category showed characteristics midway between the Low Travel Need and High Travel Need categories. Moderate Travel Need respondents suggested better bus service, improve safety and better sidewalks to enhance local travel, and better bus service and improve safety to enhance regional travel. Recommendations by Low Travel Need Respondents - Seniors in the Low Travel Need category expressed a desire for improved local bus services and for improved sidewalks and crosswalks that would make their ambulation easier.

Long, Morrison, Balog

14

In summary, improvements in bus service were the most frequently suggested travel enhancement. Improvements in paratransit service were the least frequently suggested enhancement. It is interesting to note that improvements in bus service were the most frequently selected travel enhancement by respondents living in three of the suburban jurisdictions - Anne Arundel, Carroll, and Howard Counties. While this study indicates that seniors have an active interest in enhanced transit service, it sheds little light on how many seniors would actually use such enhanced services if they were available.

COMPARABILITY OF STUDY FINDINGS WITH 1995 NPTS

At various intervals, several federal agencies sponsor a nationwide survey of personal travel in the United States. NPTS surveys have been conducted in 1969, 1977, 1983, 1990, and 1995. The agencies sponsoring the 1995 NPTS were: Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), Bureau of Transportation Statistics (BTS), Federal Transit Administration (FTA), and National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). As described in the 1995 NPTS Users Guide1 The NPTS is a tool in the urban transportation planning process; it provides data on personal travel behavior, trends in travel over time, trip generation rates, national data to use as a benchmark in reviewing local data, and data for various other planning and modeling applications. (pp 1-3) The 1995 NPTS is available in two formats. The Public Use NPTS data files omit much data that identifies specific geographic areas where respondents live. It is impossible to analyze Public Use data at local jurisdictional levels. However, professional researchers may sign a confidentiality agreement and receive the DOT version of the NPTS. This version removes all of the personal identifier information from the survey, but includes geographic locators such as the state, jurisdiction, zip, telephone area code, and telephone prefix for each respondent. The DOT version also includes other information, such as exact age of respondent, that has been aggregated into categories in the Public Use version. Ketron obtained the DOT version of the 1995 NPTS to provide comparison data for the Elderly Travel Study. The object was to compare selected NPTS data with Elderly Travel Study data to identify areas of agreement and/or items of inconsistency. To determine the reliability of the findings of the Elderly Travel Study, the trip making as recorded in the travel diaries maintained by 63 seniors living in the Baltimore region who participated in the 1995 NPTS was compared with trip making recorded in the travel diaries maintained by Elderly Travel Study respondents. With a very few exceptions, the NPTS data confirmed the findings of the Elderly Travel Study, including major trip purposes, trip distribution, and trip distance data.

1

1995 NPTS USERS GUIDE FOR THE PUBLIC USE DATA FILES; Research Triangle Institute and the Federal Highway Administration, October 1997, Publication Number FHWA-PL-98-002

Long, Morrison, Balog

15

Data from the 1995 NPTS confirmed that the Elderly Travel Study is accurate within its prescribed margin of error.

STUDY CONCLUSIONS

Information gathered in the Elderly Travel Study documents that: Baltimore region seniors are an active and growing population group, most of whom drive and travel by automobile, and to a very limited degree, use public fixed route transit and paratransit services. Approximately 92% of all trips taken by seniors are in automobiles, with seniors driving alone comprising approximately 58% of all senior trips. There is no social program that could supplant this level of senior driving and automobile travel. However, significantly enhanced public transportation and paratransit could possibly become more readily available options for seniors when their driving abilities are diminished. More work is needed to determine what attributes of public transportation and paratransit could be strengthened or marketed more effectively to seniors. Approximately 79% of seniors who live in the five suburban jurisdictions and 65% of seniors who live in Baltimore City are in the Low Travel Need category of seniors who travel as freely as they desire, do not rely on outside transportation assistance, and are not significantly impaired by physical disabilities. This group supports enhanced public transportation services, particularly in the suburban jurisdictions, and possibly would be interested in older driver programs. Approximately 13% of seniors in suburban jurisdictions and 26% of seniors in Baltimore City are in the Moderate Travel Need category of seniors characterized by moderately frequent travel, reliance on family and friends for longer-distance (but not short-distance) travel, mild physical disabilities and no drivers license or reduced driving. This group supports enhanced public transportation services, but is more concerned about safety and security in public places than seniors in the Low Travel Need group. Drivers in this category seem to experience typical older driver problems more than seniors in the Low Travel Need category and possibly would be more interested in older driver programs. Approximately 7% to 8% of seniors in all six Baltimore region jurisdictions are in the High Travel Need category. This category of seniors is characterized by traveling out of their houses infrequently, having a moderate to severe physical disability, and being reliant on friends and family for both short and long-distance travel. This category of infrequent travelers slightly favors improvements in paratransit services over improvements in fixedroute transit services, and is obviously concerned about safety and security issues while in public. In-place retirement among Baltimore region Pre-Baby Boom seniors is an extremely widespread phenomenon. This study documented that there is a minimal propensity of Baltimore region seniors to move by travel need category, age of respondent, or jurisdiction of residence. It is clear that the social responsibility of jurisdictions in the Baltimore region

Long, Morrison, Balog

16

to address the travel and other needs of older residents will not be mitigated by relocation of seniors out of their current residences. The Elderly Travel Study provides significant documentation of the activity patterns and travel characteristics of seniors (age 65+) in the Baltimore region. These findings should greatly assist in the development of public policies that seek to extend safe, independent mobility for seniors, and to develop feasible travel options for seniors, especially in High Travel Need and Moderate Travel Need categories.

You might also like

- The Iowa State Patrol Fatality Reduction Enforcement Effort (FREE)Document9 pagesThe Iowa State Patrol Fatality Reduction Enforcement Effort (FREE)epraetorianNo ratings yet

- Sample Respondents of The StudyDocument2 pagesSample Respondents of The StudyMichael Qoi Laguilay40% (5)

- Annual Report 2014 Press ReleaseDocument2 pagesAnnual Report 2014 Press ReleaseAnonymous 2zbzrvNo ratings yet

- New Urbanism and TransportDocument28 pagesNew Urbanism and TransportusmanafzalarchNo ratings yet

- Getting Millennials Fromatob: The City Loop Bus Will Board at Spots #6, 7 or 8 Based On Arrival OrderDocument36 pagesGetting Millennials Fromatob: The City Loop Bus Will Board at Spots #6, 7 or 8 Based On Arrival OrderAnonymous 2zbzrvNo ratings yet

- Dangerous by DesignDocument20 pagesDangerous by DesignSAEHughesNo ratings yet

- Helmet Compliance - Condition of Habal-Habal Drivers in Metro Cebu Revised-with-cover-page-V2Document21 pagesHelmet Compliance - Condition of Habal-Habal Drivers in Metro Cebu Revised-with-cover-page-V2San TyNo ratings yet

- Level of Awareness of Selected Drivers On Traffic LawsDocument9 pagesLevel of Awareness of Selected Drivers On Traffic Lawskayeannejusto3No ratings yet

- Design Urban Transport Systems Older PopulationDocument1 pageDesign Urban Transport Systems Older PopulationSamiNo ratings yet

- Travel Mode Choice of The ElderlyDocument10 pagesTravel Mode Choice of The ElderlyShan BasnayakeNo ratings yet

- Mobility Characteristics of The Elderly and Their Associated Level of Satisfaction With Transport ServicesDocument12 pagesMobility Characteristics of The Elderly and Their Associated Level of Satisfaction With Transport ServicesShan BasnayakeNo ratings yet

- Helmet Compliance Condition of Habal HabDocument20 pagesHelmet Compliance Condition of Habal HabMikiesha SumatraNo ratings yet

- Bebe Gurl ThesisDocument33 pagesBebe Gurl Thesismalanaalter06No ratings yet

- Final Comm PlanDocument18 pagesFinal Comm PlanROZAN CHAYA MARQUEZNo ratings yet

- P299 Reynaldo - Final Research ProposalDocument12 pagesP299 Reynaldo - Final Research ProposalShamah ReynaldoNo ratings yet

- Perceptions of Motorcycle Riders in Ra 10054 Motorcycle Helmet Act of 2009Document8 pagesPerceptions of Motorcycle Riders in Ra 10054 Motorcycle Helmet Act of 2009Damianus AbunNo ratings yet

- Public Participation PlanDocument21 pagesPublic Participation PlanbethanywilcoxonNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER II TuazonDocument11 pagesCHAPTER II TuazonLester GarciaNo ratings yet

- Demand Determinants For Urban Public Transport ServicesDocument52 pagesDemand Determinants For Urban Public Transport ServicesRajesh KhadkaNo ratings yet

- Daong RevisedDocument4 pagesDaong RevisedJohn Albert De VillaNo ratings yet

- Sample Introduction Traffic Alignment ActivityDocument5 pagesSample Introduction Traffic Alignment ActivitySobaNo ratings yet

- Philippine StudiesDocument29 pagesPhilippine StudiesRic-Ric CabugNo ratings yet

- Mapping Informal Public Transport Termin PDFDocument24 pagesMapping Informal Public Transport Termin PDFemmanjabasaNo ratings yet

- Legislative Meeting Packet Feb 2012Document31 pagesLegislative Meeting Packet Feb 2012cticotskyNo ratings yet

- Dot 65841 DS1Document234 pagesDot 65841 DS1soghraNo ratings yet

- Legislative Meeting Packet Feb 2012Document31 pagesLegislative Meeting Packet Feb 2012cticotskyNo ratings yet

- Crystal City Multi Modal Transportation StudyDocument83 pagesCrystal City Multi Modal Transportation StudyCrystalCityStreetcarNo ratings yet

- 2006 - Paez Et Al - Elderly Mobility Demographic and Spatial Analysis of Trip Making in The Hamilton CMADocument33 pages2006 - Paez Et Al - Elderly Mobility Demographic and Spatial Analysis of Trip Making in The Hamilton CMARow Ordinary'sNo ratings yet

- Retail Travel Behavior Sociodemographic With Cluster AnalysisDocument21 pagesRetail Travel Behavior Sociodemographic With Cluster AnalysisrifzafakhrialNo ratings yet

- Chapter123 Research PresentationDocument27 pagesChapter123 Research PresentationApple MestNo ratings yet

- Business Policy Written Report - Traffic PolicyDocument16 pagesBusiness Policy Written Report - Traffic PolicyelaisajericagonzalesNo ratings yet

- Operational Plan - Bantay Karapatan Sa Halalan 2016Document10 pagesOperational Plan - Bantay Karapatan Sa Halalan 2016Lex Tamen CoercitorNo ratings yet

- Are We Facing Economic Gridlock - Bonnie Crombie's 'Focus On Five' E-Newsletter (May 13-27th)Document12 pagesAre We Facing Economic Gridlock - Bonnie Crombie's 'Focus On Five' E-Newsletter (May 13-27th)CrombieWard5No ratings yet

- Us - Dot - Bureau of Transportation Statistics - Freedom To Travel - EntireDocument52 pagesUs - Dot - Bureau of Transportation Statistics - Freedom To Travel - EntireprowagNo ratings yet

- Introduction!Document3 pagesIntroduction!AvinashOgiralaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Travel Characteristicsof Elders in BeijingDocument11 pagesAnalysis of Travel Characteristicsof Elders in BeijingShan BasnayakeNo ratings yet

- Impact of Covid-19 Among Public Commuters in Cotabato City Problem and Its BackgroundDocument17 pagesImpact of Covid-19 Among Public Commuters in Cotabato City Problem and Its BackgroundWalter MamadNo ratings yet

- Lessons Learned Report 1 2008Document16 pagesLessons Learned Report 1 2008Glenn RobinsonNo ratings yet

- The Problem and Its BackgroundDocument28 pagesThe Problem and Its BackgroundKristle R BacolodNo ratings yet

- Muibi Ola CorrectedDocument88 pagesMuibi Ola CorrecteddicksonNo ratings yet

- Transit Mobile PaymentsDocument19 pagesTransit Mobile PaymentsvalenciaNo ratings yet

- Transpo Case Study (Chapter 1-5) Group 9Document28 pagesTranspo Case Study (Chapter 1-5) Group 9Macy Bautista33% (3)

- State of The Region FINAL PrintDocument60 pagesState of The Region FINAL PrintAnonymous Feglbx5No ratings yet

- 1212121Document7 pages1212121XDXDXDNo ratings yet

- CORE Excluded EnglishDocument78 pagesCORE Excluded EnglishBurma PartnershipNo ratings yet

- 3 RdtopicDocument2 pages3 RdtopicAldrei John MalanaNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Travel Characteristics and Access Mode Choice of Elderly Urban Rail Riders in Denver, ColoradoDocument13 pagesAnalysis of Travel Characteristics and Access Mode Choice of Elderly Urban Rail Riders in Denver, ColoradoShan BasnayakeNo ratings yet

- Practicality - Negative SideDocument3 pagesPracticality - Negative SideMa. Theresa VillarinNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument14 pagesUntitledShaira Jane Villareal AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Kulang Kulang Thesis 1.0Document11 pagesKulang Kulang Thesis 1.0Kell LynoNo ratings yet

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument31 pagesReview of Related LiteratureRyle AquinoNo ratings yet

- Political DevolopmentDocument12 pagesPolitical DevolopmentKresha Parreñas100% (1)

- PTEG - Urban-Transport-Policies - FINAL For WebDocument60 pagesPTEG - Urban-Transport-Policies - FINAL For Webalyssa suyatNo ratings yet

- The Function of Public Transportation in Alleviating Traffic Congestion (AutoRecovered)Document4 pagesThe Function of Public Transportation in Alleviating Traffic Congestion (AutoRecovered)krizziahannekilapioNo ratings yet

- City Council 20240403 PacketDocument3 pagesCity Council 20240403 PacketIndiana Public Media NewsNo ratings yet

- Transportation for the Elderly: Changing Lifestyles, Changing NeedsFrom EverandTransportation for the Elderly: Changing Lifestyles, Changing NeedsNo ratings yet

- Governing the Fragmented Metropolis: Planning for Regional SustainabilityFrom EverandGoverning the Fragmented Metropolis: Planning for Regional SustainabilityNo ratings yet

- Leading the localities: Executive mayors in English local governanceFrom EverandLeading the localities: Executive mayors in English local governanceNo ratings yet

- Gridlock: Why We're Stuck in Traffic and What To Do About ItFrom EverandGridlock: Why We're Stuck in Traffic and What To Do About ItRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- USCSDocument1 pageUSCSLamija AhmetspahićNo ratings yet

- Wavin PVC Pressure Pipe Systems Product and Technical Guide: Intelligent Solutions ForDocument1 pageWavin PVC Pressure Pipe Systems Product and Technical Guide: Intelligent Solutions ForGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Approved Cross Sections 3Document1 pageApproved Cross Sections 3Giora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Paper No. 01-2601: Leedoseu@pilot - Msu.eduDocument26 pagesPaper No. 01-2601: Leedoseu@pilot - Msu.eduGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- KEMBLA CatalogueDocument13 pagesKEMBLA CatalogueGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Soil - FillingDocument6 pagesSoil - FillingGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Construction and Performance of Ultra-Thin Bonded Hma Wearing CourseDocument26 pagesConstruction and Performance of Ultra-Thin Bonded Hma Wearing CourseGiora Rozmarin100% (1)

- Development of Critical Field Permeability and Pavement Density Values For Coarse-Graded Superpave PavementsDocument30 pagesDevelopment of Critical Field Permeability and Pavement Density Values For Coarse-Graded Superpave PavementsGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Constitutive Modeling of The Flexural Fatigue Performance of Fiber Reinforced and Lightweight ConcretesDocument18 pagesConstitutive Modeling of The Flexural Fatigue Performance of Fiber Reinforced and Lightweight ConcretesGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Paper No. TRB #01-3486 Development of Testing Procedures To Determine The Water-Cement Ratio of Hardened Portland Cement Concrete Using Semi-Automated Image Analysis TechniquesDocument14 pagesPaper No. TRB #01-3486 Development of Testing Procedures To Determine The Water-Cement Ratio of Hardened Portland Cement Concrete Using Semi-Automated Image Analysis TechniquesGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- A Consultant's Perspective of Highway Network Asset Management Practice in EnglandDocument8 pagesA Consultant's Perspective of Highway Network Asset Management Practice in EnglandGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Niittymaki@hut - Fi: Development of Integrated Air Pollution Modelling Systems For Urban Planning-DIANA ProjectDocument18 pagesNiittymaki@hut - Fi: Development of Integrated Air Pollution Modelling Systems For Urban Planning-DIANA ProjectGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Congestion Pricing and Roadspace Rationing: An Application To The San Francisco Bay Bridge CorridorDocument18 pagesCongestion Pricing and Roadspace Rationing: An Application To The San Francisco Bay Bridge CorridorGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- TRB ID: 01-3271: Polydor@Document17 pagesTRB ID: 01-3271: Polydor@Giora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- 00149Document21 pages00149Giora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- AC A S T Gis D: Learinghouse Pproach To Haring Ransportation ATADocument16 pagesAC A S T Gis D: Learinghouse Pproach To Haring Ransportation ATAGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Paper No. 01-2558: Title: Commuter Rail Station Governance and Parking PracticesDocument20 pagesPaper No. 01-2558: Title: Commuter Rail Station Governance and Parking PracticesGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Comparative Evaluation of Field Performance of Pavement Marking Products On Alternative Test Deck DesignsDocument23 pagesComparative Evaluation of Field Performance of Pavement Marking Products On Alternative Test Deck DesignsGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of Commuter Activity Scheduling and Sequencing Behavior Across Geographical ContextsDocument28 pagesA Comparison of Commuter Activity Scheduling and Sequencing Behavior Across Geographical ContextsGiora RozmarinNo ratings yet

- Concrete Slab Track State of The Practice: TRB Paper No. 01-0240Document32 pagesConcrete Slab Track State of The Practice: TRB Paper No. 01-0240Giora Rozmarin0% (1)

- Passing ReportDocument1 pagePassing Reportmht1No ratings yet

- Century Class ST and Coronado Driver's ManualDocument239 pagesCentury Class ST and Coronado Driver's ManualJohn AdamsNo ratings yet

- AOADocument7 pagesAOANitin SaxenaNo ratings yet

- VeloCity2011 Presentation Cycling AlbaniaDocument31 pagesVeloCity2011 Presentation Cycling AlbaniaDorina PojaniNo ratings yet

- SIDRA INTERSECTION - MODEL FUNDAMENTALS WORKSHOP Contents - 2019Document3 pagesSIDRA INTERSECTION - MODEL FUNDAMENTALS WORKSHOP Contents - 2019Marcelo QuintanilhaNo ratings yet

- Fuel Issues Form: م ش ش تامدخلاو تايرفحلل ةينطولا ةكرشلا National Drilling & Services Co. L.L.CDocument1 pageFuel Issues Form: م ش ش تامدخلاو تايرفحلل ةينطولا ةكرشلا National Drilling & Services Co. L.L.Ccmrig74No ratings yet

- LOTboarding PassDocument2 pagesLOTboarding PassbisonshotNo ratings yet

- Ahemdabad Case StudyDocument41 pagesAhemdabad Case StudyAr Kajal GangilNo ratings yet

- MB/L No - DMM209522 B/L No. 301-19-44854-301457: Combined Transport Bill of LadingDocument6 pagesMB/L No - DMM209522 B/L No. 301-19-44854-301457: Combined Transport Bill of LadingsravanNo ratings yet

- SCHOOL BASED ASSIGNMENT Geo (SJW)Document26 pagesSCHOOL BASED ASSIGNMENT Geo (SJW)Drippy PacNo ratings yet

- Tourism and CultureDocument5 pagesTourism and CultureLouise Marithe FlorNo ratings yet

- 6E 2134 1015 Hrs Zone 2 17F: Boarding Pass (Web Check In)Document2 pages6E 2134 1015 Hrs Zone 2 17F: Boarding Pass (Web Check In)alondraortega07No ratings yet

- JamshedpurDocument12 pagesJamshedpurविशालविजयपाटणकरNo ratings yet

- Airline Production PlanningDocument13 pagesAirline Production PlanningFadhlurrohman AziziNo ratings yet

- Place Making As An Approach To Revitalize Neglected Urban Open SpacesDocument10 pagesPlace Making As An Approach To Revitalize Neglected Urban Open SpacesSandra SamirNo ratings yet

- Stand-On Stacker Ergo Ajn 160Sdtfv: Mast Type Lift Height H Height of Mast Lowered h1 Max Mast Height h4Document2 pagesStand-On Stacker Ergo Ajn 160Sdtfv: Mast Type Lift Height H Height of Mast Lowered h1 Max Mast Height h4Xb ZNo ratings yet

- Incorporating Online Home Delivery ServicesDocument2 pagesIncorporating Online Home Delivery ServicesSead RizvanovićNo ratings yet

- Highway: Geometric DesignDocument33 pagesHighway: Geometric DesignGabriel Abanto QueseaNo ratings yet

- Completed Report Dissatisfaction 7-20-2023 1-48-08 PMDocument3 pagesCompleted Report Dissatisfaction 7-20-2023 1-48-08 PMCs ServiceNo ratings yet

- SAFMC Logbook: By: Nicole, Rui Yao and Guang YuanDocument17 pagesSAFMC Logbook: By: Nicole, Rui Yao and Guang YuansimpNo ratings yet

- R AFPam 10-1403 Air Mobility Planning Factors PDFDocument27 pagesR AFPam 10-1403 Air Mobility Planning Factors PDFStephen SmithNo ratings yet

- Business - Traveller.uk June.2023Document78 pagesBusiness - Traveller.uk June.2023Daniel dAzNo ratings yet

- Sample Vesselsearch Table f3I3yayz6TDocument4 pagesSample Vesselsearch Table f3I3yayz6TLuis Enrique RomeroNo ratings yet

- Regenerative Braking in Trains MinorDocument25 pagesRegenerative Braking in Trains Minormanish guptaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Road Damages in The Flow of Traffic in Iloilo CityDocument18 pagesThe Effect of Road Damages in The Flow of Traffic in Iloilo CityJudy ann RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Terberg RT283 PDFDocument2 pagesTerberg RT283 PDFHemerson FurtadoNo ratings yet

- Accident Analysis and Prevention: Thomas Kerwin, Brad J. Bushman TDocument7 pagesAccident Analysis and Prevention: Thomas Kerwin, Brad J. Bushman TJuan Pablo GMNo ratings yet

- Mec 531 Project Title Sept2013-Jan2014Document3 pagesMec 531 Project Title Sept2013-Jan2014arina azharyNo ratings yet

- Dynamic Seat ReservoirDocument1 pageDynamic Seat Reservoirmr.sithulwin22No ratings yet

- JRC Pipe RecoveryDocument16 pagesJRC Pipe RecoveryJean CarloNo ratings yet