Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Draconaki Et Al. (2011) - Efficacy of Ultrasound-Guided Steroid Injections For Pain Management of Midfoot Joint Degenerative Disease

Draconaki Et Al. (2011) - Efficacy of Ultrasound-Guided Steroid Injections For Pain Management of Midfoot Joint Degenerative Disease

Uploaded by

xtraqrkyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Draconaki Et Al. (2011) - Efficacy of Ultrasound-Guided Steroid Injections For Pain Management of Midfoot Joint Degenerative Disease

Draconaki Et Al. (2011) - Efficacy of Ultrasound-Guided Steroid Injections For Pain Management of Midfoot Joint Degenerative Disease

Uploaded by

xtraqrkyCopyright:

Available Formats

Skeletal Radiol (2011) 40:10011006 DOI 10.

1007/s00256-010-1094-y

SCIENTIFIC ARTICLE

Efficacy of ultrasound-guided steroid injections for pain management of midfoot joint degenerative disease

Eleni E. Drakonaki & James S. B. Kho & Robert J. Sharp & Simon J. Ostlere

Received: 7 October 2010 / Revised: 22 December 2010 / Accepted: 29 December 2010 / Published online: 28 January 2011 # ISS 2011

Abstract Objective To examine the efficacy of ultrasound (US)guided injections for midfoot joint degenerative changes. Materials and methods The US images and radiographs of 63 patients with midfoot joint degenerative changes were retrospectively reviewed. In those patients who had USguided intra-articular steroid injection, the response to the injection was recorded by reviewing the 2-week pain diaries and clinical notes. Partial or complete pain relief was defined as a positive response and the same or increased level of pain as a negative response to the injection. Results Fifty-nine (59/63, 93.6%) patients with midfoot joint degenerative changes received US-guided injection. The majority of patients had a positive response up to 3 months post-injection (78.4% still experiencing pain relief at 2 weeks, 57.5% at 3 months and fewer than 15% of patients further than 3 months post-injection). The number of positive therapeutic responses did not differ significantly between patients with diagnostic and nondiagnostic response (p =0.2636). Conclusions US-guided intra-articular injections for midfoot degenerative changes can have a good therapeutic result in the majority of patients up to 3 months postinjection. Therapeutic response cannot be predicted by a positive diagnostic response.

E. E. Drakonaki (*) : J. S. B. Kho : S. J. Ostlere Department of Radiology, Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre NHS Trust, Windmill Road, Headington, Oxford OX3 7LD, UK e-mail: drakonaki@yahoo.gr R. J. Sharp Department of Orthopaedics , Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre NHS Trust, OX3 7LD, Oxford, UK

Keywords Midfoot osteoarthritis . Ultrasound . Guided injections

Introduction Ultrasound (US) is well established as a useful technique in demonstrating joint pathology and is widely used in the diagnosis and management of inflammatory arthritis [1]. Ultrasound is sensitive in detecting even minimal osteophytes, joint effusion, synovial proliferation, and hypervascularity, and can be used to monitor the effect of systematic therapy and to guide the intra-articular delivery of drugs [1]. US-guided injections have been proven to be more accurate than those performed blind or with the aid of fluoroscopy [1, 2]. Although US imaging has been widely applied in the clinical practice for the pain management of degenerative changes, there is limited published evidence regarding its efficacy and clinical utility [311]. The aim of this retrospective observational study is to examine the clinical utility of US for the pain management of midfoot joint degenerative changes by evaluating the diagnostic and therapeutic effect of US-guided corticosteroid/local anesthetic injections.

Materials and methods This retrospective study included patients with midfoot degenerative changes who were referred to the radiology department of our hospital for US examination and USguided intra-articular corticosteroid/local anesthetic injection. This retrospective study was performed following the Declaration of Helsinki principles.

1002

Skeletal Radiol (2011) 40:10011006

The recruitment of patients comprising the study group was performed as follows: The Picture Archiving and Communication System (PACS) of our hospital was searched for referrals for US examinations and US-guided injections in midfoot joints (tarsometatarsal, calcaneocuboid, naviculocuneiform, and talonavicular joints) over a period of 3 years. Referrals with evidence of inflammatory arthropathy, either at the time of the injection or during follow-up, were excluded from the study. To allow comparisons between US and radiographs, only cases where both investigations were performed within a period of 6 months of each other were included. This amounted to 63 cases, which formed the study group. All US examinations and US-guided injections were performed by five musculoskeletal consultants with more than 10 years of dedicated musculoskeletal experience or by four musculoskeletal radiology fellows under the supervision of one of the consultants. All examinations were performed using commercially available ultrasound systems (Antares Sonoline; Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA, and Philips HDI 5000 Advanced Technologies Laboratories, Bothel, WA) with high-frequency lineararray transducers ranging from 5 to 13 MHz and settings depending on personal preference. Patients were referred for injection by the Podiatric or Foot and Ankle services of our hospital. The US images and reports and the pre-US foot and ankle radiographs of the 63 cases were reviewed for evidence of midfoot joint degenerative changes by a consultant and a fellow in musculoskeletal radiology, in consensus. For US, the presence of synovial hypertrophy and osteophytes identified on the US images or described in the report was regarded as evidence of degenerative changes. For the radiographs, the presence of joint space loss accompanied by either osteophytes or subchondral sclerosis/cysts was regarded as evidence of degenerative changes. All pre-US radiographic views of the area of interest available in the system were reviewed. To assess the effectiveness of the corticosteroid/local anesthetic injections for midfoot OA, the pain diaries and clinical notes of the patients were reviewed. Pain diaries covered a period of 2 weeks following the injection. The patients were asked to qualitatively describe the postinjection pain level compared to the pre-injection pain level at specific time points (end of the first day, end of the second day, 1 week, and 2 weeks after the injection) by selecting one of following categories: worse, same, better, no pain (grades 03, respectively). The technique used to perform the injection does not vary substantially between operators in our department. Ultrasound is initially used to plan the optimum approach and, following infiltration with local anesthetic, a needle is guided into the joint cavity and maneuvered to allow free

flow of fluid into the joint. The injected material is a mixture of 11.5 ml of a long-acting local anesthetic solution (Bupivacaine hydrochloride 0.5%, Marcain Polyamp Streripack 0.5%, 10 ml, AstraZeneca, Luton, UK) and 20 to 40mgs of corticosteroid (Methylprednisolone acetate BP, Depomedrone 1 ml, 40 mg/vial, Pharmacia Ltd, Kent, UK). Following the procedure, pain diaries are given to the patients, who are instructed to complete the questionnaire over the next 2 weeks and mail it back to the department. All pain diaries and notes available were reviewed by a fellow in musculoskeletal radiology. The reported level of pain at the end of the first day and at 2 weeks post-injection was used to assess the diagnostic and the short-term therapeutic effect of the injection, respectively. The diagnostic/therapeutic effect was assumed as positive, if better or no pain was reported at the specific time points, indicating complete or partial pain relief, respectively (grades 2, 3, respectively). The diagnostic/therapeutic effect was assumed as negative, if same or worse was reported at the specific time points, indicating no pain relief or increase in the amount of pain, respectively (grades 1, 0, respectively). In patients with a positive short-term therapeutic effect (at 2 weeks), the long-term therapeutic effect of the injection (further than 2 weeks) was evaluated by reviewing the clinical notes. A longer-term positive therapeutic effect was recorded if there was evidence that the patient was completely asymptomatic or experienced substantial pain relief, if the patient was satisfied with the effect of the injection, or would consider another injection in case the pain recurs. The reported duration of the positive therapeutic effect was categorized according to the following time periods: 24 weeks, 13 months, 36 months, 612 months, and >12 months post-injection. A negative therapeutic effect was recorded in case the following information was included in the notes: the patient had no substantial pain relief or there was more pain than prior to the injection or the patient would not consider having a second injection or the patient was referred for alternative treatment. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 8.0 for Windows, SPSS Inc, Chicago, Il, USA). Fishers test was employed to assess the difference in the number of positive diagnostic and therapeutic injections between patients with findings in US only and patients with changes in both examinations. The McNemar test was employed to assess differences between patients with diagnostic and non-diagnostic response. Statistical significance was set at p <0.05.

Results The study group included 63 patients in total (22 men, 41 women, mean age 6510.6 years, minimum 55 years,

Skeletal Radiol (2011) 40:10011006

1003

maximum 82 years) who underwent US examinations of the midfoot joints for clinically suspected degenerative disease. All patients (63/63, 100%) had presented with midfoot tenderness and pain, 55/63 (87.3%) of patients with swelling over the dorsum of the midfoot and 6/63 (9.5%) patients had history of prior surgery or fracture. Ultrasound examination revealed signs of midfoot degenerative changes in 59/63 (93.6%) patients and plain radiographs in 45/63 (71.4%) patients. The mean time interval between the US and radiographic examinations was 163 weeks (minimum 2 weeks, maximum 24 weeks) and the radiographic views available included anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views of the foot in 43 cases, AP and oblique in nine cases, AP, lateral, and oblique views in eight cases and AP views in only three cases (Figs. 1, 2). All 59 patients with US signs of midfoot joint degenerative changes were injected. Fifty-one patients (51/59, 86.4%) returned their pain diaries. The outcome of the injections is presented in Tables 1 and 2. The effect was positive in 34/51 (66.7%) patients during the first day, in 39/51 (76.5%) at the end of the first week and 40/51 (78.4%) at the end of the second week post-injection

(Table 1). The injection had a positive diagnostic and shortterm therapeutic effect in 27/51 (52.9%) patients and a negative diagnostic and short-term therapeutic effect in 4/ 51 (7.8%) patients (Table 2). In 7/51 (13.7%) patients, the injection had a positive diagnostic and a short-term negative therapeutic effect and in 13/51 (25.5%) patients there was a negative diagnostic but positive short-term therapeutic effect (Table 2). The number of short-term positive therapeutic responses did not differ significantly between patients with diagnostic and non-diagnostic response (McNemar test, p =0.2636, Table 2). There was no statistically significant difference in the number of positive therapeutic responses between patients with evidence of degenerative changes only in US and patients with degenerative changes in both US and radiographs (76.9 and 75%, respectively, Fishers exact test, p =1). Data regarding the longer-term outcome of the injection (further than 2 weeks) were available in 40/51 patients. In 11/51 patients, the notes were either not available or noninformative. The patients were followed-up through the notes until pain had returned. A positive therapeutic effect was still evident in 27/40 (67.5%) patients at 24 weeks, in

Fig. 1 Plain radiographs and US images of a 52-year-old female with pain and swelling over the left first tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint. Anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) radiograph of the left foot demonstrates degenerative changes with joint space narrowing, osteophytes, and subchondral sclerosis, predominantly apparent on the AP view. Longitudinal color Doppler US image of the left first TMT joint (c) shows prominent osteophytes and synovial thickening with increased Doppler signal, corresponding to neovascularity.

Longitudinal B-mode US image (d) shows the linear echogenic needle entering the joint. An intra-articular injection of corticosteroid/ local anesthetic was performed under direct US guidance. The patient reported complete pain relief at 1 day, indicating a positive diagnostic effect and partial pain relief at the end of the second week, indicating a positive therapeutic effect. The review of the notes revealed that the patient still had less pain up to 2 months after the procedure and was given a second injection 3 months later

1004

Skeletal Radiol (2011) 40:10011006

Fig. 2 Plain radiograph and US images of a 50-year-old female with pain and swelling over the left fourth tarsometatarsal (TMT) joint. Although anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) radiographs of the left foot demonstrate no definite signs of degenerative changes, there are questionable osteophytes arising from the medial base of the fourth metatarsal and the contiguous cuboid. Short-axis color Doppler US image of the left fourth TMT joint (c) shows degenerative changes with definite bone irregularity and synovial thickening with increased

Doppler signal. d Longitudinal B-mode US image showing the linear echogenic needle entering the joint to deliver the mixture of corticosteroid/local anesthetic. The patient reported partial pain relief on the first day and at the end of the second week, indicating a positive diagnostic and short-term therapeutic effect. The review of the notes revealed that pain was back at pre-injection levels 3 weeks after the injection

23/40 (57.5%) patients at 13 months, in 6/40 (15%) patients at 36 months, in 4/40 (10%) at 612 months and in one patient (1/40, 2.5%) at 20 months (Table 1). No complications to the injection were recorded.

Table 1 Short- and long-term outcome of ultrasound-guided steroid injections for midfoot joint degenerative changes, presented at six time points: at the end of the first day and at the end of the first week and second week (based on the pain diaries) and 24 weeks, 13 months, Outcome Positive Grade 2 Grade 3 Negative Grade 1 Grade 0 Total 1 day 34/51 (66.7%) 26 8 17/51 (33.3%) 10 7 51 1 week 39/51 (76.5%) 32 7 12/51 (23.5%) 10 2 51 2 weeks 40/51 (78.4%) 30 10 11/51 (21.6%) 10 1 51 24 weeks 27/40 (67.5%)

Discussion Although US-guided corticosteroid intra-articular injections have been used in clinical practice for the management of

36 months, 612 months, and further than 12 months after the injection (based on patient notes). Grading: 0=worse, 1=same level of pain, 2=better and 3=no pain after the injection 13 months 23/40 (57.5%) 36 months 6/40 (15%) 612 months 4/40 (10%) >12 months 1/40 (2.5%)

13/40 (32.5%)

17/40 (42.5%)

34/40 (85%)

36/40 (90%)

39/40 (97.5%)

40

40

40

40

40

Skeletal Radiol (2011) 40:10011006 Table 2 Diagnostic and short-term therapeutic effect of US-guided corticosteroid/local anesthetic injections for midfoot joint degenerative disease. The diagnostic and the short-term therapeutic effects correspond to level of pain at the end of the first day and at 2 weeks post-injection, respectively Short-term therapeutic effect Diagnostic effect Positive Negative Total Positive 27 13 40 Negative 7 4 11 Total 34 17 51

1005

McNemar test for paired proportions, p =0.2636. Statistical significance set at 0.05. (x2 =1.250 with 1 of freedom, odds ratio=1.857, 95% confidence interval

range=0.6895.497)

degenerative disease, little published evidence currently exists on their efficacy for reducing pain in the foot and ankle region [11]. More evidence exists on the effectiveness of intra-articular viscosupplementation (hyaluronic acid) injections for treating foot degenerative disease [1214]. A randomized placebo-controlled trial comparing intraarticular hyaluronic acid to corticosteroid injection in the first metatarsophalangeal joint found that, although both drugs produced significant symptom improvement, the effects were longer lasting for viscosupplementation compared to corticosteroids [14]. The only prospective study assessing the effect of foot intra-articular corticosteroid injections in 18 patients with osteoarthritis or rheumatoid arthritis using validated region specific questionnaires found a significant improvement up to 6 months postinjection with maximal improvement at 4 weeks and a further decline over time [10]. We found that the duration of the therapeutic effect of the US-guided intra-articular injections was varied. There was good to excellent pain relief up to 3 months after the injection, with the majority of patients (57.5%) still experiencing pain relief up to 3 months post-injection and a dramatic decline in the number of effective injections (less than 15% of patients) further than 3 months post-injection. Therefore, although there is considerable variation in the duration of the response, it seems that there is a role for corticosteroid injections for managing pain from midfoot joint degenerative changes for up to 3 months. An important issue is the recognition of specific prognostic factors that would predict a positive postinjection response. A previous study did not identify any independent clinical prognostic factors [10]. In our study, the number of patients experiencing a short-term therapeutic response did not differ significantly between those with a diagnostic and a non-diagnostic effect, thus suggesting that a diagnostic response does not predict a therapeutic

response. The purpose of a diagnostic joint injection is to deliver a local anesthetic with a particular length of action into the joint [15]. Depending on the duration of the response compared to the expected action of the anesthetic agent, it is possible to determine whether a particular joint is the source of the patients complaint [15]. We choose to use bupivacaine, an agent with an anesthetic duration of approximately 45 h, because it helps to reduce the incidence of the painful flare response that occasionally accompanies percutaneous steroid injections [16]. In 13.7% of our cases, there was a positive diagnostic but a negative therapeutic response, suggesting that the pain was actually originating from the particular joint that was injected but the corticosteroid was ineffective in reducing the inflammation and prolonging the therapeutic effect [17]. Interestingly, in 25.5% of cases there was a negative diagnostic but a positive therapeutic response, suggesting that either the local anesthetic was not effective for some indefinable reason (such as the steroid flare phenomenon) or that the pain did not originate from that particular joint, despite the apparent beneficial effect from the steroid injection. It is possible that some of these patients experienced coincidental spontaneous resolution of the symptoms, although the likelihood of this occurring is low, taking into account that all the cases had long-standing pain. A study on knee osteoarthritis has recently shown that patients with non-inflammatory characteristics on US had a longer benefit from intra-articular corticosteroids [9]. In the present study, it was not possible to assess the impact of the US imaging features on the duration of response, as retrospective grading of B-mode and Doppler findings would have been inaccurate. However, our findings suggest that the presence of radiological changes does not have significant implications on the outcome of the US-guided injections, as patients with degenerative changes only on US responded similarly to patients with changes on both US and radiographs. We recognize the presence of several limitations in this study, most of which are related to its retrospective design. A major limitation is that the long-term outcome of the injections was assessed by reviewing the patient notes, thus leading to some inevitable compromise in quantifying of the exact duration and the level of pain relief. To overcome this problem, and to minimize the subjectivity of the results, we categorized the phrases most commonly encountered in the notes into groups, we used larger time periods instead of exact time point, and binary outcome groups (yes/no pain relief) instead of subgroups indicating level of pain. The duration of symptoms prior to referral was also not recorded; however, all cases must have been longstanding, as it usually takes several months for a national health care system patient to complete the pathway from primary care to US-guided injection. Another limitation is

1006

Skeletal Radiol (2011) 40:10011006 4. Keen HI, Conaghan PG. Usefulness of ultrasound in osteoarthritis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35:50319. 5. Keen HI, Wakefield RJ, Conaghan PG. A systematic review of ultrasonography in osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:6119. 6. Chao J, Kalunian K. Ultrasonography in osteoarthritis: recent advances and prospects for the future. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20:5604. 7. Mller I, Bong D, Naredo E, et al. Ultrasound in the study and monitoring of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16 Suppl 3:S47. 8. Meenagh G, Filippucci E, Iagnocco A, et al. Ultrasound imaging for the rheumatologist VIII. Ultrasound imaging in osteoarthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2007;25:1725. 9. Chao J, Wu C, Sun B, et al. Inflammatory characteristics on ultrasound predict poorer long-term response to intraarticular corticosteroid injections in knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2010;37:6505. 10. Ward ST, Williams PL, Purkayastha S. Intra-articular corticosteroid injections in the foot and ankle: a prospective 1-year followup investigation. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2008;47:13844. 11. Peterson C, Hodler J. Evidence-based radiology (part 2): Is there sufficient research to support the use of therapeutic injections into the peripheral joints? Skeletal Radiol. 2010;39:118. 12. Sun SF, Chou YJ, Hsu CW, et al. Efficacy of intra-articular hyaluronic acid in patients with osteoarthritis of the ankle: a prospective study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14:86774. 13. Munteanu SE, Menz HB, Zammit GV, et al. Efficacy of intraarticular hyaluronan (Synvisc) for the treatment of osteoarthritis affecting the first metatarsophalangeal joint of the foot (hallux limitus): study protocol for a randomised placebo-controlled trial. J Foot Ankle Res. 2009;2:2. 14. Pons M, Alvarez F, Solana J, Viladot R, Varela L. Sodium hyaluronate in the treatment of hallux rigidus: a single-blind, randomized study. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:3842. 15. Newman JS. Diagnostic and therapeutic injections of the foot and ankle. Semin Roentgenol. 2004;39:8594. 16. Middleton F, Coakes J, Umarji S, Palmer S, Venn R, Panayiotou S. The efficacy of intra-articular bupivacaine for relief of pain following arthroscopy of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:16035. 17. Klint E, Grundtman C, Engstrom M, et al. Intraarticular glucocorticoid treatment reduces inflammation in synovial cell infiltrations more efficiently than in synovial blood vessels. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:3880889. 18. Lo GH, LaValley M, McAlindon T, Felson DT. Intra-articular hyaluronic acid in treatment of knee osteoarthritis: a metaanalysis. JAMA. 2003;290:311521. 19. Manchikanti L, Hirsch JA, Smith HS. Evidence-based medicine, systematic reviews and guidelines in interventional pain management: Part 2: Randomized controlled trials. Pain Physician. 2008;11:71773. 20. Bolton JE. The evidence in evidence-based practice: What counts and what doesn t count? J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2001;24:3626.

associated with the subjectivity in describing the level of pain. The impact of different levels of activity and the possible use of pain killers were not taken into consideration. As they were not systematically reported, the fact that injections were performed by several radiologists may have influenced the success of the procedure and the radiographic projections used were not standardized. Another issue is the lack of a control group, so the placebo effect of the injection cannot be assessed. Although the placebo effect for intra-articular injections of viscosupplementation is reported to be as high as 76% [18], placebo-controlled studies on knee and foot osteoarthritis have shown that corticosteroid/local anesthetic injections were still more effective than the placebo [9, 16]. Although the need of randomized placebo-controlled trials using detailed pain scoring systems is considered desirable in the era of evidence-based medicine [19], clinically relevant observational studies are ethically more solid and reflect the actual patient population more closely [19, 20]. In conclusion, this retrospective study shows US-guided intra-articular corticosteroid/local anesthetic injections for midfoot joint degenerative changes can achieve good shortand medium-term results. The presence of radiologic changes and the diagnostic effect of the injections cannot predict a positive therapeutic effect. Further prospective studies are needed to assess the clinical role of US and USguided injections for pain management of degenerative joint disease.

Conflict of Interest The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Cheung PP, Dougados M, Gossec L. Reliability of ultrasonography to detect synovitis in rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature review of 35 studies (1, 415 patients). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62:32334. 2. Reach JS, Easley ME, Chuckpaiwong B, Nunley JA. Accuracy of ultrasound guided injections in the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30:23942. 3. Keen HI, Conaghan PG. Ultrasonography in osteoarthritis. Radiol Clin North Am. 2009;47:58194.

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

You might also like

- Philip Merlan, From Platonism To NeoplatonismDocument267 pagesPhilip Merlan, From Platonism To NeoplatonismAnonymous fgaljTd100% (1)

- Park 2014Document7 pagesPark 2014Nurfitrianti ArfahNo ratings yet

- Comparison Between Outcomes of Dry Needling With Conventional Protocol and Rood's Approach With Conventional Protocol On Pain, Strength and Balance in Knee OsteoarthritisDocument29 pagesComparison Between Outcomes of Dry Needling With Conventional Protocol and Rood's Approach With Conventional Protocol On Pain, Strength and Balance in Knee OsteoarthritisDrPratibha SinghNo ratings yet

- Massage Therapy For Osteoarthritis of The KneeDocument6 pagesMassage Therapy For Osteoarthritis of The KneeDrAbhay ShankargoudaNo ratings yet

- Tascioglu Et Al 2010 Short Term Effectiveness of Ultrasound Therapy in Knee OsteoarthritisDocument10 pagesTascioglu Et Al 2010 Short Term Effectiveness of Ultrasound Therapy in Knee Osteoarthritiskrishnamunirajulu1028No ratings yet

- Rajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, KarnatakaDocument13 pagesRajiv Gandhi University of Health Sciences, Bangalore, KarnatakaR HariNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Correlation Between TMD and Cervical Spine Pain and Mobility: Is The Whole Body Balance TMJ Related?Document8 pagesResearch Article: Correlation Between TMD and Cervical Spine Pain and Mobility: Is The Whole Body Balance TMJ Related?gloriagaskNo ratings yet

- Nice 1stDocument6 pagesNice 1staldiNo ratings yet

- Surgical Versus Nonsurgical Therapy For Lumbar Spinal StenosisDocument17 pagesSurgical Versus Nonsurgical Therapy For Lumbar Spinal StenosisIbnu 'AsyiqinNo ratings yet

- Meta-Analysis Evaluating Music Interventions For Anxiety and Pain in SurgeryDocument11 pagesMeta-Analysis Evaluating Music Interventions For Anxiety and Pain in SurgeryMifta FauziayahNo ratings yet

- FisioterapiDocument7 pagesFisioterapiRidwan Hadinata SalimNo ratings yet

- Clinical Study: Autologous Blood Injection and Wrist Immobilisation For Chronic Lateral EpicondylitisDocument6 pagesClinical Study: Autologous Blood Injection and Wrist Immobilisation For Chronic Lateral EpicondylitistriptykhannaNo ratings yet

- Effect of Isometric Quadriceps Exercise On Muscle StrengthDocument7 pagesEffect of Isometric Quadriceps Exercise On Muscle StrengthAyu RoseNo ratings yet

- Vertebroplastia Evidencia 1 USADocument11 pagesVertebroplastia Evidencia 1 USAandres donnetNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0003999319303892 MainDocument8 pages1 s2.0 S0003999319303892 MainRizkyrafiqoh afdinNo ratings yet

- 4 FQB GN 7 C YTf 5 GM FJJ PRs DZyDocument8 pages4 FQB GN 7 C YTf 5 GM FJJ PRs DZygck85fj8pnNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Ultrasound Treatment For The Management of KDocument7 pagesThe Effectiveness of Ultrasound Treatment For The Management of Kkrishnamunirajulu1028No ratings yet

- Journal ESWT Pada DewasaDocument7 pagesJournal ESWT Pada DewasaPhilipusHendryHartonoNo ratings yet

- Use of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation Device in Early Osteoarthritis of The KneeDocument7 pagesUse of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation Device in Early Osteoarthritis of The KneeAlifah Nisrina Rihadatul AisyNo ratings yet

- Article 4Document10 pagesArticle 4umair muqriNo ratings yet

- Ijss Aug Oa12Document5 pagesIjss Aug Oa12Herry HendrayadiNo ratings yet

- Short-Wave Diathermy in The Treatment of Knee OsteoarthritisDocument10 pagesShort-Wave Diathermy in The Treatment of Knee Osteoarthritisapi-462099014No ratings yet

- Judul, Pengantar, Tujuan Dan MetodeDocument3 pagesJudul, Pengantar, Tujuan Dan MetodenurrahmiNo ratings yet

- Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy VersusDocument7 pagesExtracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy VersusGiannis SaramantosNo ratings yet

- 2013 Knee Prolotherapy RCTDocument9 pages2013 Knee Prolotherapy RCTReyn JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Ebm in Ultrasounds and Schock WavesDocument35 pagesEbm in Ultrasounds and Schock Wavessabina vladeanuNo ratings yet

- Abat 2016Document8 pagesAbat 2016toaldoNo ratings yet

- Short-Term Recovery From HipDocument4 pagesShort-Term Recovery From Hipdamien333No ratings yet

- Comparison of The Efficacy of Physical Therapy andDocument5 pagesComparison of The Efficacy of Physical Therapy andfi.afifah NurNo ratings yet

- Effects of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation On Pain Pain Sensitivity and Function in People With Knee Osteoarthritis. A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument14 pagesEffects of Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation On Pain Pain Sensitivity and Function in People With Knee Osteoarthritis. A Randomized Controlled TrialLorena Rico ArtigasNo ratings yet

- Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy For Sacroiliac Joint Pain: A Prospective, Randomized, Sham-Controlled Short-Term TrialDocument7 pagesExtracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy For Sacroiliac Joint Pain: A Prospective, Randomized, Sham-Controlled Short-Term TrialLizeth Tatiana Ortiz PalominoNo ratings yet

- OA Manual Therapy ArticleDocument14 pagesOA Manual Therapy ArticlekapilphysioNo ratings yet

- Ilter 2015Document8 pagesIlter 2015Ahmad Awaludin TaslimNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review of Diagnostic Utility and Therapeutic Effectiveness of Thoracic Facet Joint InterventionsDocument19 pagesSystematic Review of Diagnostic Utility and Therapeutic Effectiveness of Thoracic Facet Joint InterventionsRongalaSnehaNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Chronic Pain On Postoperative PaiDocument12 pagesThe Influence of Chronic Pain On Postoperative PairflaviogjNo ratings yet

- Tangtiphaiboontana 2021Document8 pagesTangtiphaiboontana 2021翁嘉聰No ratings yet

- Jmu 26 194Document6 pagesJmu 26 194Arkar SoeNo ratings yet

- Predictors of Pain Resolution After Varicocelectomy For Painful VaricoceleDocument5 pagesPredictors of Pain Resolution After Varicocelectomy For Painful VaricoceleMuhammad AndilaNo ratings yet

- Clinical StudyDocument8 pagesClinical Studylilis pratiwiNo ratings yet

- Assessing Pain Relief Following Medical and Surgical Interventions For Lumbar Disc HerniationDocument4 pagesAssessing Pain Relief Following Medical and Surgical Interventions For Lumbar Disc HerniationInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- 1472 6882 13 55 PDFDocument16 pages1472 6882 13 55 PDFUlfaAmaliaFajrinNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument12 pagesUntitledapi-243703329No ratings yet

- Artigo - US Pra Dor CrônicaDocument12 pagesArtigo - US Pra Dor CrônicaJose Carlos CamposNo ratings yet

- JCM 08 00051 v2Document7 pagesJCM 08 00051 v2joelruizmaNo ratings yet

- Prospective, Controlled & Randomized Study: With & Without Epiduroscopy AssistanceDocument1 pageProspective, Controlled & Randomized Study: With & Without Epiduroscopy AssistanceProf. Dr. Ahmed El MollaNo ratings yet

- KNEST Keg438Document7 pagesKNEST Keg438jsyugesh21No ratings yet

- Acupuncture in Patients With Osteoarthritis of The Knee: A Randomised TrialDocument9 pagesAcupuncture in Patients With Osteoarthritis of The Knee: A Randomised TrialDiana PiresNo ratings yet

- CA Glar 2016Document7 pagesCA Glar 2016bdhNo ratings yet

- 1 UsDocument7 pages1 UsJenny VibsNo ratings yet

- Articulo de HombroDocument8 pagesArticulo de HombroYesenia OchoaNo ratings yet

- Diagnostic Values of Tests For Acromioclavicular Joint PainDocument6 pagesDiagnostic Values of Tests For Acromioclavicular Joint Painarum_negariNo ratings yet

- Suprascapular Nerve Block Versus Steroid Injection For Non-Specific Shoulder PainDocument7 pagesSuprascapular Nerve Block Versus Steroid Injection For Non-Specific Shoulder PainTri KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Bed Angels On PainDocument12 pagesBed Angels On PainNiken AninditaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment in PDocument7 pagesEffects of Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment in PbesombespierreNo ratings yet

- Bernadeth P. Solomon BSN Lll-A The Effectiveness of Motorised Lumbar Traction in The Management of LBP With Lumbo Sacral Nerve Root Involvement: A Feasibility Study Annette A Harte1Document5 pagesBernadeth P. Solomon BSN Lll-A The Effectiveness of Motorised Lumbar Traction in The Management of LBP With Lumbo Sacral Nerve Root Involvement: A Feasibility Study Annette A Harte1roonnNo ratings yet

- Effective Use of Viscosupplementation After Knee Arthroscopy: Experience From A Working GroupDocument10 pagesEffective Use of Viscosupplementation After Knee Arthroscopy: Experience From A Working GroupIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Pain, Trunk Muscle Strength, Spine Mobility and Disability Following Lumbar Disc SurgeryDocument5 pagesPain, Trunk Muscle Strength, Spine Mobility and Disability Following Lumbar Disc Surgerye7choevaNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Therapeutic Facet Joint Interventions in Chronic Spinal PainDocument26 pagesA Systematic Review of Therapeutic Facet Joint Interventions in Chronic Spinal PainJulie RoseNo ratings yet

- Auriculotherapy For Pain Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled TrialsDocument12 pagesAuriculotherapy For Pain Management: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled TrialsSol Instituto TerapêuticoNo ratings yet

- Critical AppraisalDocument13 pagesCritical AppraisalRatna Widiyanti KNo ratings yet

- Pearson - Age-Associated Changes in Blood Pressure in A Longitudinal Study of Healthy Men & WomenDocument7 pagesPearson - Age-Associated Changes in Blood Pressure in A Longitudinal Study of Healthy Men & WomenxtraqrkyNo ratings yet

- Braun Et Al. (2007) - Diagnosis and Management of Nail PigmentationsDocument13 pagesBraun Et Al. (2007) - Diagnosis and Management of Nail PigmentationsxtraqrkyNo ratings yet

- Leung (2008) - Familial Melanonychia StriataDocument4 pagesLeung (2008) - Familial Melanonychia StriataxtraqrkyNo ratings yet

- Selim (2008) - Melanonychia A Question of DensityDocument2 pagesSelim (2008) - Melanonychia A Question of DensityxtraqrkyNo ratings yet

- Morrison & Ferrari (2009) - Inter-Rater Reliability of The Foot Posture Index (FPI-6) in The Assessment of The Paediatric FootDocument6 pagesMorrison & Ferrari (2009) - Inter-Rater Reliability of The Foot Posture Index (FPI-6) in The Assessment of The Paediatric FootxtraqrkyNo ratings yet

- Harris Et Al. (2004) - Diagnosis and Treatment of Pediatric FlatfootDocument33 pagesHarris Et Al. (2004) - Diagnosis and Treatment of Pediatric FlatfootxtraqrkyNo ratings yet

- Fitzpatricks Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology - Exfoliative Erythroderma SyndromeDocument17 pagesFitzpatricks Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology - Exfoliative Erythroderma SyndromextraqrkyNo ratings yet

- Sehgal Et Al. (2004) - Erythroderma :exfoliative Dermatitis - A SynopsisDocument9 pagesSehgal Et Al. (2004) - Erythroderma :exfoliative Dermatitis - A SynopsisxtraqrkyNo ratings yet

- Guwahati: Places To VisitDocument5 pagesGuwahati: Places To Visitdrishti kuthariNo ratings yet

- Solar MPPT PresentationDocument21 pagesSolar MPPT PresentationPravat SatpathyNo ratings yet

- Us - Tsubaki - Sprocket - Catalog 2Document199 pagesUs - Tsubaki - Sprocket - Catalog 2Jairo Andrés FANo ratings yet

- Traffic Flow - WikipediaDocument146 pagesTraffic Flow - WikipediaAngeline AgunatNo ratings yet

- Jul-Sep 2008 Voice For Native Plants Newsletter, Native Plant Society of New MexicoDocument16 pagesJul-Sep 2008 Voice For Native Plants Newsletter, Native Plant Society of New Mexicofriends of the Native Plant Society of New MexicoNo ratings yet

- Capacity PlanDocument1 pageCapacity PlanbishnuNo ratings yet

- Preparation of Paracetamol Post LabDocument5 pagesPreparation of Paracetamol Post Labshmesa_alrNo ratings yet

- Jaisalmer - Secular ArchitectureDocument12 pagesJaisalmer - Secular Architecturearpriyasankar12No ratings yet

- Deluge Valve Installation ManualDocument7 pagesDeluge Valve Installation Manualrahull.miishraNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Matchemphys 2019 05 033Document13 pages10 1016@j Matchemphys 2019 05 033Deghboudj SamirNo ratings yet

- Jean AttachmentDocument17 pagesJean AttachmentReena VermaNo ratings yet

- Pronoun Reference - Exercise 5: Correction Should Sound Natural and Be LogicalDocument4 pagesPronoun Reference - Exercise 5: Correction Should Sound Natural and Be LogicalPreecha ChanlaNo ratings yet

- Firearms in America 1600 - 1899Document310 pagesFirearms in America 1600 - 1899Mike100% (3)

- Siskyou Bombing RangeDocument114 pagesSiskyou Bombing RangeCAP History LibraryNo ratings yet

- Twinkle For Heather Challenge V2Document63 pagesTwinkle For Heather Challenge V2gillian.cartwrightNo ratings yet

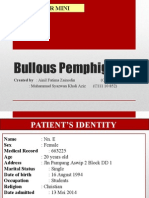

- Bullous PemphigoidDocument21 pagesBullous PemphigoidChe Ainil ZainodinNo ratings yet

- Ray OpticsDocument6 pagesRay OpticsshardaviharphysicsNo ratings yet

- 26 MatricesDocument26 pages26 MatricesFazli KamawalNo ratings yet

- Key AnDocument17 pagesKey Anpro techNo ratings yet

- 11thMachAutoExpo 2022Document112 pages11thMachAutoExpo 2022Priyanka KadamNo ratings yet

- Accepted Manuscript: Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & ReviewsDocument43 pagesAccepted Manuscript: Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & ReviewsYanet FrancoNo ratings yet

- Manual of - Installation - Operation - Maintenance Light Oil and Biodiesel Burners Progressive and Fully Modulating Versions PG30 PG90 PG510 PG60 PG91 PG515 PG70 PG92 PG520 PG80 PG81Document52 pagesManual of - Installation - Operation - Maintenance Light Oil and Biodiesel Burners Progressive and Fully Modulating Versions PG30 PG90 PG510 PG60 PG91 PG515 PG70 PG92 PG520 PG80 PG81OSAMANo ratings yet

- Balsa Wood BridgeDocument31 pagesBalsa Wood BridgeAlvin WongNo ratings yet

- WBC AnomaliesDocument20 pagesWBC AnomaliesJosephine Piedad100% (1)

- ESP Front Page Idea Aravinth 2Document10 pagesESP Front Page Idea Aravinth 2adcreation3696No ratings yet

- What Hartmann'S Solution Is and What It Is Used For?Document4 pagesWhat Hartmann'S Solution Is and What It Is Used For?YudhaNo ratings yet

- Acceleration Theory & Business Cycles: Sem Ii - MebeDocument14 pagesAcceleration Theory & Business Cycles: Sem Ii - MebePrabhmeet SethiNo ratings yet

- Appendix 11 Design FMEA ChecklistDocument16 pagesAppendix 11 Design FMEA ChecklistDearRed FrankNo ratings yet

- Quail Farming Business Plan PDF OverviewDocument5 pagesQuail Farming Business Plan PDF OverviewhenrymcdoNo ratings yet