Professional Documents

Culture Documents

General Introduction: Amplypterus From Borneo (J. Beck & N. Blüthgen, Unpubl.) - Ambulycini Appear Intermediate

General Introduction: Amplypterus From Borneo (J. Beck & N. Blüthgen, Unpubl.) - Ambulycini Appear Intermediate

Uploaded by

Superb HeartOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

General Introduction: Amplypterus From Borneo (J. Beck & N. Blüthgen, Unpubl.) - Ambulycini Appear Intermediate

General Introduction: Amplypterus From Borneo (J. Beck & N. Blüthgen, Unpubl.) - Ambulycini Appear Intermediate

Uploaded by

Superb HeartCopyright:

Available Formats

GENERAL INTRODUCTION

range of body sizes among the family there are differences in average body size and -shape between the subfamilies - Macroglossinae have shorter wings and a larger thorax in relation to the wing size than other subfamilies (chapter 5.2), a fact that could influence flight abilities and dispersal of the taxa. Most adult Sphingidae feed an flower nectar which presumably allows them to imbibe energy in the form of carbohydrates, but probably only few proteins or amino acids. Adult search for amino acids or protein, which occurs in other taxa an flowers (e.g. Alm et al. 1990, Erhardt & Baker 1990, Erhardt 1991, Dunlap-Pianka et al. 1979, see also Blthgen & Fiedler 2004a, b and references therein) and elsewhere (Beck et al. 1999, Bnziger 1975, 1979, 1980, 1986), has not been studied in detail in the Sphingidae, but there are indications of nitrogen-related ` mud-puddling' in various species (Bnziger 1988, Bttiker 1973). Furthermore, some unusual adult feeding habits occur, such as stealing honey from bee's nests (in Acherontia sp.) and tear-drinking an large mammals (Bnziger 1988). Very little is known about the specificity of flower visits of adult hawkmoths, but it has been observed that Sphingidae apparently remember the location of rich nectar sources and visit them again (Janzen 1984, Pittaway 1997). Many Smerinthinae, particularly of the tribus Smerinthini, are not feeding as adults (as may be concluded from a missing or reduced proboscis; it is to date not really clear if this is a plesiomorphic character within the Sphingidae, I.J. Kitching pers. com .), while the adult feeding habits and their ecological consequences (see below) in the tribus Ambulycini (see table 1) requires further attention. Ambulycini have a reduced, yet probably functional proboscis, an which flower pollen were found in six species of the genera Ambulyx and Amplypterus from Borneo (J. Beck & N. Blthgen, unpubl.). Ambulycini appear intermediate between the non-feeding Smerinthini and the feeding adults of other subfamilies, with a larval biology similar to the former group, but traits of Sphinginae- or Macroglossinae adult behaviour (see also chapter 7 for discussion). Adult diet has an influence an life-span and egg production in Lepidoptera (e.g. Karlson 1994, Hill 1989, Hainsworth et al. 1991). The lack of adult feeding in some groups is i nfluencing their life-history with probably far-reaching ecological and behavioural consequences (e.g. Tammaru & Haukioja 1996, see also Janzen 1984 for a thorough discussion): Non-feeding adults have to produce all eggs from larval resources (capital breeders), while their adult life is presumably relatively short. Feeding adults, an the other hand, can use adult resources for egg production and body maintenance (income breeders), and thus have a potential for a longer adult life-span (see also the discussion of semelparous vs. iteroparous organisms in Begon et al. 1996). Parasitoids from a wide range of taxa are known to attack hawkmoth eggs and caterpillars of the Western Palaearctic region (see Pittaway 1997 for details), including nematode worms, Hymenoptera (Trichogrammatidae, Ichneumonidae, Braconidae) and Diptera (Tachinidae), which can lead to a mortality of up to 80 percent in some investigated caterpillar populations (see Pittaway 1997 for references). Known predators of larva and adults are invertebrates (ants, social wasps, beetles, spiders) as well as vertebrates (mice, shrews, birds, bats, cats; Pittaway 1997, Giardini 1993). Sphingidae rely mostly an crypsis as a means of predator escape, but eyespots (as snake-mimicry) in caterpillars and startling pink and yellow hindwings in adults occur in some taxa (Kitching & Cadiou 2000). Sequestration of toxic secondary plant compounds for protection against predators is apparently rare (Kitching &

You might also like

- Stamp Bulletin 272 (Oct Dec 2003)Document37 pagesStamp Bulletin 272 (Oct Dec 2003)martinagmNo ratings yet

- Acherontia SP.), While It Could Be Related To Yet Unexplored Mating Behaviour in Other CasesDocument1 pageAcherontia SP.), While It Could Be Related To Yet Unexplored Mating Behaviour in Other CasesSuperb HeartNo ratings yet

- Agaricomycetes: Mushroom-Forming FungiDocument13 pagesAgaricomycetes: Mushroom-Forming FungiOliver SHNo ratings yet

- Agaricomycetes: Mushroom-Forming FungiDocument9 pagesAgaricomycetes: Mushroom-Forming FungiOliver SHNo ratings yet

- Indian Meal Moth (Hubner)Document15 pagesIndian Meal Moth (Hubner)shko noshaNo ratings yet

- Molecular Phylogeny of The Phytoparasitic Mite FamilyDocument38 pagesMolecular Phylogeny of The Phytoparasitic Mite Familymaria riveraNo ratings yet

- 7 - Biotic InteractionsDocument22 pages7 - Biotic InteractionsJorge Botia BecerraNo ratings yet

- Cactus ReviewDocument20 pagesCactus ReviewLinx_ANo ratings yet

- 202 The Regulatory Anatomy of Honeybee LifespanDocument20 pages202 The Regulatory Anatomy of Honeybee LifespanPablo ACNo ratings yet

- Amancio Et Al. - 2019 - Feeding Specialization of Flies (Diptera RichardiDocument7 pagesAmancio Et Al. - 2019 - Feeding Specialization of Flies (Diptera Richardigualu_pi_ta_No ratings yet

- tmp841D TMPDocument12 pagestmp841D TMPFrontiersNo ratings yet

- AscomycetesDocument24 pagesAscomycetesEsteban Jose De VirgilioNo ratings yet

- Butterfly PDFDocument24 pagesButterfly PDFzakir hussainNo ratings yet

- 7 - Biotic Interactions - 2001 - Behavioral Ecology of Tropical BirdsDocument20 pages7 - Biotic Interactions - 2001 - Behavioral Ecology of Tropical BirdsYesid MedinaNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Value and Use of Microalgae in Aquaculture: Malcolm R. BrownDocument12 pagesNutritional Value and Use of Microalgae in Aquaculture: Malcolm R. BrownClaudia Andrea Sanchez SanderNo ratings yet

- 爬行动物和益生菌Document22 pages爬行动物和益生菌Xiaoqiang KeNo ratings yet

- Fleming Et Al 2009Document27 pagesFleming Et Al 2009DANIEL POSADA GUTIERREZNo ratings yet

- Biological Control: Luc Barbaro, Andrea BattistiDocument8 pagesBiological Control: Luc Barbaro, Andrea Battistinima2020No ratings yet

- Studies On Biology and Reproduction of Butterflies (Family: Papilionidae) in Nilgiris Hills, Southern Western Ghats, IndiaDocument11 pagesStudies On Biology and Reproduction of Butterflies (Family: Papilionidae) in Nilgiris Hills, Southern Western Ghats, IndiaEman SamirNo ratings yet

- Review Hatchery TechnologyDocument6 pagesReview Hatchery Technologylucia_bregNo ratings yet

- Fleming Et Al. 2009 - The Evolution of Bat Pollination - A Phylogenetic PerspectiveDocument27 pagesFleming Et Al. 2009 - The Evolution of Bat Pollination - A Phylogenetic PerspectiveMarcelo MorettoNo ratings yet

- Lecture 10 Notes 2013Document3 pagesLecture 10 Notes 2013Richard HampsonNo ratings yet

- Hojun Song 2018Document25 pagesHojun Song 2018johanna abrilNo ratings yet

- Identification, Biology and Use of The Predator Stinkbug Podisus NigrispinusDocument7 pagesIdentification, Biology and Use of The Predator Stinkbug Podisus NigrispinusxpldroxNo ratings yet

- Fleming Et Al 2009Document27 pagesFleming Et Al 2009Simon Garth PurserNo ratings yet

- Butterfly-Farming The Flying Gems by Labay PIFGEX 2009Document30 pagesButterfly-Farming The Flying Gems by Labay PIFGEX 2009Anonymous HXLczq375% (4)

- Brian Final ProjectDocument25 pagesBrian Final ProjectEdward MuiruriNo ratings yet

- Phytoliths As Indicators of Pedogenesis and Paleoenvironmental Changes in The Brazilian CerradoDocument5 pagesPhytoliths As Indicators of Pedogenesis and Paleoenvironmental Changes in The Brazilian Cerradokaname10No ratings yet

- Seed Storage ProteinsDocument12 pagesSeed Storage ProteinsChandra LekhaNo ratings yet

- Coccinellidae As Predators of Mites PDFDocument16 pagesCoccinellidae As Predators of Mites PDFJulian LeonardoNo ratings yet

- Spodoptera Litura - CPHST Datasheet - 2014 - 2Document15 pagesSpodoptera Litura - CPHST Datasheet - 2014 - 2shahid attaNo ratings yet

- Heithaus 1982Document41 pagesHeithaus 1982DANIEL POSADA GUTIERREZNo ratings yet

- Taygetis Cleopatra Ms For Submission Rev1 TT EDFINAL Rev MRMDocument7 pagesTaygetis Cleopatra Ms For Submission Rev1 TT EDFINAL Rev MRMRoberto CrepesNo ratings yet

- Biology Form 3 NotesDocument75 pagesBiology Form 3 NotesFar taNo ratings yet

- Larvae 3Document81 pagesLarvae 3Kenaia AdeleyeNo ratings yet

- Floral Rewards and Pollination in Cytiseae (Fabaceae) : Plant Systematics and Evolution May 2003Document12 pagesFloral Rewards and Pollination in Cytiseae (Fabaceae) : Plant Systematics and Evolution May 2003AngelaNo ratings yet

- Control of Invertebrate Occupants of Nests: August 2015Document2 pagesControl of Invertebrate Occupants of Nests: August 2015MHS MEUTIA SOLEHAHNo ratings yet

- Proteína de InsectosDocument5 pagesProteína de InsectosLauraNo ratings yet

- Fungal Sex: The Basidiomycota: Marco Coelho, Guus Bakkeren, Sheng Sun, Michael Hood, Tatiana GiraudDocument30 pagesFungal Sex: The Basidiomycota: Marco Coelho, Guus Bakkeren, Sheng Sun, Michael Hood, Tatiana GiraudRui MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Asociación Planta OrmigaDocument4 pagesAsociación Planta OrmigaDaniel Aparicio HilaresNo ratings yet

- Willow Salix PDFDocument22 pagesWillow Salix PDFsamNo ratings yet

- Marone Et Al 2017 Diet Switching of Seed-Eating Birds Wintering in Grazed Habitats of The Central Monte ArgentinaDocument11 pagesMarone Et Al 2017 Diet Switching of Seed-Eating Birds Wintering in Grazed Habitats of The Central Monte ArgentinaagustinzarNo ratings yet

- Mushroom CultivationDocument37 pagesMushroom CultivationRISHI ANIRUDH MNo ratings yet

- Fru RaygrassDocument13 pagesFru RaygrassPablo Peralta RoaNo ratings yet

- Fleming 1994Document8 pagesFleming 1994José Manuel HoyosNo ratings yet

- Phylogenetic Analysis of Eurytominae (Chalcidoidea: Eurytomidae) Based On Morphological CharactersDocument70 pagesPhylogenetic Analysis of Eurytominae (Chalcidoidea: Eurytomidae) Based On Morphological CharactersAna MaríaNo ratings yet

- 2 - Breeding SeasonsDocument14 pages2 - Breeding SeasonsJorge Botia BecerraNo ratings yet

- 1.1 Taxonomy of ActinomycetesDocument8 pages1.1 Taxonomy of ActinomycetesLinguumNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Flora 2019 151528Document36 pages10 1016@j Flora 2019 151528oscardckotsNo ratings yet

- Insectsin Forensic InvestigationsDocument18 pagesInsectsin Forensic InvestigationsJudicaëlNo ratings yet

- Marine Ecology - 2011 - Cecere - Vegetative Reproduction by Multicellular Propagules in Rhodophyta An OverviewDocument19 pagesMarine Ecology - 2011 - Cecere - Vegetative Reproduction by Multicellular Propagules in Rhodophyta An OverviewKathya Gómez AmigoNo ratings yet

- CBO9780511902451A015Document20 pagesCBO9780511902451A015Veronica B MarinaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Crop ProtectionDocument22 pagesIntroduction To Crop ProtectionaaNo ratings yet

- Beautiful Portraits !Document6 pagesBeautiful Portraits !Berengere HAUETNo ratings yet

- Family PteromalidaeDocument25 pagesFamily PteromalidaeSimone BM MinduimNo ratings yet

- 70 232 1 PB3 PDFDocument41 pages70 232 1 PB3 PDFRosa Quezada DanielNo ratings yet

- 1 IntoDocument8 pages1 IntoJuneville Vincent AndoNo ratings yet

- Biology Review 5.4 and 5.5 - IB DiplomaDocument5 pagesBiology Review 5.4 and 5.5 - IB DiplomaRosa PietroiustiNo ratings yet

- See AlsoDocument2 pagesSee AlsoJonee SansomNo ratings yet

- Seed Predation and Dispersal by PeccarieDocument39 pagesSeed Predation and Dispersal by PeccarieCarlos ZaniniNo ratings yet

- Tenses ExplanationsDocument22 pagesTenses ExplanationsSuperb HeartNo ratings yet

- Company: ElectricityDocument3 pagesCompany: ElectricitySuperb HeartNo ratings yet

- Construction Management Including Review of CONSTRUCTION Contractors' Schedules, QA/QC, Field Inspection, and Progress ReportingDocument1 pageConstruction Management Including Review of CONSTRUCTION Contractors' Schedules, QA/QC, Field Inspection, and Progress ReportingSuperb HeartNo ratings yet

- Saudl Geetricity Company: Qurayyah Combined Cycle Power Plant, Extension (BlockDocument1 pageSaudl Geetricity Company: Qurayyah Combined Cycle Power Plant, Extension (BlockSuperb HeartNo ratings yet

- I.,t :.a.".. L L: Schepule Contract NoDocument1 pageI.,t :.a.".. L L: Schepule Contract NoSuperb HeartNo ratings yet

- Instrumentation and Control 8.1: PTS # 06EG902Document1 pageInstrumentation and Control 8.1: PTS # 06EG902Superb HeartNo ratings yet

- Saudi Electricity CompanyDocument2 pagesSaudi Electricity CompanySuperb HeartNo ratings yet

- 6.4.8.5 Reagents: PTS # 06EG902Document1 page6.4.8.5 Reagents: PTS # 06EG902Superb HeartNo ratings yet

- 4.9 Spare Parts: PTS # 06EG902Document2 pages4.9 Spare Parts: PTS # 06EG902Superb HeartNo ratings yet

- Jo .Z :? R: Saudi Electricity CompanyDocument2 pagesJo .Z :? R: Saudi Electricity CompanySuperb HeartNo ratings yet

- Andrallus Spinidens - RiceDocument6 pagesAndrallus Spinidens - RiceAbigaile Javier-HilaNo ratings yet

- Agrotis IpsilonDocument17 pagesAgrotis IpsilonMayuri VohraNo ratings yet

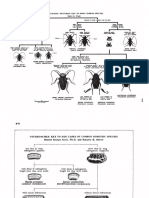

- Cockroaches: Pictorial Key To Some Common Species: Harry D. PrattDocument8 pagesCockroaches: Pictorial Key To Some Common Species: Harry D. PrattMatteo CorradoNo ratings yet

- Butterfl Ies and Moths: Teacher's Guide Classroom ActivitiesDocument54 pagesButterfl Ies and Moths: Teacher's Guide Classroom ActivitiesIPI Accounting TeamNo ratings yet

- Diversities of Butterflies in KashmirDocument11 pagesDiversities of Butterflies in KashmirMalik AsjadNo ratings yet

- Insect AriumDocument11 pagesInsect AriumBabasChongNo ratings yet

- AEN 301 2019 Batch VERY SHORT NOTESDocument39 pagesAEN 301 2019 Batch VERY SHORT NOTESMd Arief SyedNo ratings yet

- Drain Fly - Google Search 3Document1 pageDrain Fly - Google Search 3ayu diana awangNo ratings yet

- Article: Contribution To The Knowledge of Ephemeroptera (Insecta) From Goiás State, BrazilDocument15 pagesArticle: Contribution To The Knowledge of Ephemeroptera (Insecta) From Goiás State, BrazilErikcsen Augusto RaimundiNo ratings yet

- Care Guide: Goliath Stick Insect, Eurycnema GoliathDocument2 pagesCare Guide: Goliath Stick Insect, Eurycnema GoliathDionisius D. SutantoNo ratings yet

- 2015 Catalog WebDocument32 pages2015 Catalog WebmealysrNo ratings yet

- Pelatihan Budidaya Sebagai Pakan Burung Puyuh Untuk Masyarakat Di Desa Batee Puteh Kecamatan Langsa LamaDocument14 pagesPelatihan Budidaya Sebagai Pakan Burung Puyuh Untuk Masyarakat Di Desa Batee Puteh Kecamatan Langsa LamaIlhan MansizNo ratings yet

- Attracting Beneficial Insects ArticleDocument3 pagesAttracting Beneficial Insects Articlein678No ratings yet

- Integrated Pest Management in OkraDocument21 pagesIntegrated Pest Management in OkraParry Grewal100% (1)

- Classification of Insects: Practical ManualDocument69 pagesClassification of Insects: Practical ManualFARZANA FAROOQUENo ratings yet

- Common Pests of Field CropsDocument37 pagesCommon Pests of Field CropsShaira MacauyagNo ratings yet

- Endang Sri Ratna - Efisiensi Parasitisasi Inang Spodoptera Litura (F.)Document9 pagesEndang Sri Ratna - Efisiensi Parasitisasi Inang Spodoptera Litura (F.)U - SoundNo ratings yet

- Morphometrics of Caste System and Colony Structure of The Asian Weaver Ant, Oecophylla Smaragdina Fabricius, 1775 (Hymenoptera Formicidae) From Cacao Farms in Luzon Island, PhilippinesDocument12 pagesMorphometrics of Caste System and Colony Structure of The Asian Weaver Ant, Oecophylla Smaragdina Fabricius, 1775 (Hymenoptera Formicidae) From Cacao Farms in Luzon Island, PhilippinesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Honey BeeDocument21 pagesHoney Beeapi-286042559100% (1)

- AfricanizedhoneybeesDocument2 pagesAfricanizedhoneybeesRodrigo MedinaNo ratings yet

- Pest of Pepper Final1Document23 pagesPest of Pepper Final1Navneet MahantNo ratings yet

- Thea's Monarch Butterfly Migration Biology Final ProjectDocument8 pagesThea's Monarch Butterfly Migration Biology Final ProjectCharles IppolitoNo ratings yet

- Read The Text Quickly and Sign The Difficult WordsDocument4 pagesRead The Text Quickly and Sign The Difficult WordsFirdaus Dwi Yulian 74934No ratings yet

- 20 Songs Butterfly Caterpillar Songs CompletedDocument8 pages20 Songs Butterfly Caterpillar Songs Completedapi-259262734No ratings yet

- Hymenoptera: (Wasps, Bees, Ants)Document46 pagesHymenoptera: (Wasps, Bees, Ants)Herold Riwaldo SNo ratings yet

- 08 SummerbugbooksDocument7 pages08 SummerbugbooksmahounololiNo ratings yet

- Pest Control2Document49 pagesPest Control2manna726No ratings yet

- PracDocument3 pagesPracsam000678No ratings yet

- Lista Publicaciones CINATDocument21 pagesLista Publicaciones CINATKenny Golfin CascanteNo ratings yet