Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Doctrine of Necessary Implication

Doctrine of Necessary Implication

Uploaded by

Yan Lean DollisonCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Cot 1 Lesson Plan Freedom of The Human PersonDocument13 pagesCot 1 Lesson Plan Freedom of The Human PersonJohn Eric Peregrino86% (14)

- Statcon NotesDocument35 pagesStatcon NotesAliNo ratings yet

- StatCon Finals ReviewerDocument13 pagesStatCon Finals ReviewerEmman Cariño100% (2)

- Privatization and Management Office v. Strategic Alliance Development CorporationDocument2 pagesPrivatization and Management Office v. Strategic Alliance Development CorporationJaypee Ortiz67% (3)

- Speech Chart of CasesDocument10 pagesSpeech Chart of CasesusflawstudentNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Necessary ImplicationDocument19 pagesDoctrine of Necessary ImplicationAivy Christine Manigos100% (1)

- Presumptions in StatconDocument40 pagesPresumptions in StatconNicole Deocaris100% (1)

- Presumptions STATCON ReportDocument13 pagesPresumptions STATCON ReportAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAANo ratings yet

- Palanca v. City of Manila and TrinidadDocument2 pagesPalanca v. City of Manila and TrinidadJanine Ismael100% (1)

- Ang Yu VS CaDocument2 pagesAng Yu VS Cairene anibongNo ratings yet

- Ting Vs Velez-TingDocument4 pagesTing Vs Velez-TingPaolo Mendioro100% (2)

- Obligations and Contracts Case Updates 2005 2014 2doc PDFDocument107 pagesObligations and Contracts Case Updates 2005 2014 2doc PDFNufa AlyhaNo ratings yet

- Exam ConstiDocument11 pagesExam ConstiAngie DouglasNo ratings yet

- Chrea Vs CHR Case DigestDocument6 pagesChrea Vs CHR Case DigestAj Guadalupe de MataNo ratings yet

- Stacon Case DigestDocument5 pagesStacon Case DigestRICKY ALEGARBESNo ratings yet

- How To Do A Case DigestDocument2 pagesHow To Do A Case DigestHK FreeNo ratings yet

- US V HartDocument2 pagesUS V HartJerahmeel CuevasNo ratings yet

- Ferrer V Bautista DigestDocument6 pagesFerrer V Bautista DigestJamiah HulipasNo ratings yet

- Obligations and Contracts Case Updates (2005-2014)Document88 pagesObligations and Contracts Case Updates (2005-2014)starryarryNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law: 1987 Constitution of The Republic of The PhilippinesDocument44 pagesConstitutional Law: 1987 Constitution of The Republic of The PhilippinesimoymitoNo ratings yet

- Calalang Vs Williams (Digest)Document1 pageCalalang Vs Williams (Digest)Stefan SalvatorNo ratings yet

- Crimpro ReviewerDocument59 pagesCrimpro ReviewerjojitusNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument25 pagesCase DigestDendi roszellsexy100% (1)

- Doctrine of Necessary ImplicationDocument1 pageDoctrine of Necessary Implicationprime100% (2)

- Political SBCDocument94 pagesPolitical SBCMDNo ratings yet

- Table of Contents Case DigestDocument9 pagesTable of Contents Case DigestBiggie DesturaNo ratings yet

- Facts:: 109. NPC V SPSDocument1 pageFacts:: 109. NPC V SPSLuna BaciNo ratings yet

- Consti Final ExamDocument39 pagesConsti Final ExamVeen Galicinao FernandezNo ratings yet

- Enrique Abad Vs Goldloop DigestDocument1 pageEnrique Abad Vs Goldloop DigestRyan Suaverdez100% (3)

- StatCon - Syllabus 2018Document13 pagesStatCon - Syllabus 2018Josiah BalgosNo ratings yet

- What Is A Breach of Promise To MarryDocument2 pagesWhat Is A Breach of Promise To MarryThina ChiiNo ratings yet

- Stat Con NotesDocument6 pagesStat Con NotesMis DeeNo ratings yet

- Summary of Manila Prince Hotel V GSISDocument3 pagesSummary of Manila Prince Hotel V GSISEros CabauatanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 - Judicial DepartmentDocument18 pagesChapter 12 - Judicial Departmentrizumu00No ratings yet

- Nitafan V Cir 152 Scra 284Document7 pagesNitafan V Cir 152 Scra 284Anonymous K286lBXothNo ratings yet

- Basic Guidelines PDFDocument3 pagesBasic Guidelines PDFSrezon HalderNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 - Maxims, Doctrines, Rules and Interpretation of The LawsDocument8 pagesChapter 7 - Maxims, Doctrines, Rules and Interpretation of The LawsVanessa Alarcon100% (2)

- Statcon Cases 7-12Document8 pagesStatcon Cases 7-12Frances Grace DamazoNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Implication DigestsDocument12 pagesDoctrine of Implication DigestsHannah TolentinoNo ratings yet

- STATCON Group 2 Legal MaximsDocument15 pagesSTATCON Group 2 Legal Maximsangelyn susonNo ratings yet

- Revalida Question 10Document2 pagesRevalida Question 10Kyle BanceNo ratings yet

- Term Paper in Statutory ConstructionDocument17 pagesTerm Paper in Statutory ConstructionMichelle VillamoraNo ratings yet

- MagdaDocument24 pagesMagdaIco AtienzaNo ratings yet

- Landbank of The Philippines vs. SantosDocument25 pagesLandbank of The Philippines vs. SantosTia RicafortNo ratings yet

- Case Name Metrobank V RosalesDocument2 pagesCase Name Metrobank V RosalesMowie AngelesNo ratings yet

- BOCEA vs. Teves Case DigestDocument2 pagesBOCEA vs. Teves Case DigestRhodz Coyoca Embalsado100% (1)

- Case No. 29 People v. Pimentel 288 SCRA 542 (1998)Document1 pageCase No. 29 People v. Pimentel 288 SCRA 542 (1998)William Christian Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-51201 May 29, 1980Document6 pagesG.R. No. L-51201 May 29, 1980Amrosy Bani BunsaNo ratings yet

- Statutory Construction and InterpretationDocument9 pagesStatutory Construction and InterpretationMichael Angelo Victoriano100% (1)

- Statcon FinalsDocument5 pagesStatcon FinalsChami PanlaqueNo ratings yet

- CIR V PRIMETOWN PROPERTY G.R. No. 162155Document3 pagesCIR V PRIMETOWN PROPERTY G.R. No. 162155Ariza Valencia100% (1)

- Republic vs. Court of Appeals (299 SCRA 199)Document4 pagesRepublic vs. Court of Appeals (299 SCRA 199)Krisleen Abrenica50% (2)

- Chua Case Spec. Pro.Document1 pageChua Case Spec. Pro.Donny WalshNo ratings yet

- Adasa v. Abalos (G.R. No. 168617)Document5 pagesAdasa v. Abalos (G.R. No. 168617)Rache Gutierrez100% (1)

- Mandatory and Directory StatutesDocument23 pagesMandatory and Directory StatutesSabir Saif Ali ChistiNo ratings yet

- Mandatory and Directory StatutesDocument23 pagesMandatory and Directory StatutesLoolu Kutty50% (2)

- Mandatory and Directory ProvisionsDocument5 pagesMandatory and Directory ProvisionsSUBRAHMANYA BHATNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 IosDocument34 pagesUnit 1 IosJibin KozhikkottuNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of Mandatory and Directory Statutes: Presented By: Rinkey Sharma Asst. Prof. of Law IilsDocument18 pagesInterpretation of Mandatory and Directory Statutes: Presented By: Rinkey Sharma Asst. Prof. of Law Iilsvenkatesha conapalliNo ratings yet

- Himmat Lal K Shah v. Commissioner of PoliceDocument6 pagesHimmat Lal K Shah v. Commissioner of PoliceSom Dutt VyasNo ratings yet

- Basic Principles of InterpretationDocument8 pagesBasic Principles of Interpretationangel mathewNo ratings yet

- THE LABOUR LAW IN UGANDA: [A TeeParkots Inc Publishers Product]From EverandTHE LABOUR LAW IN UGANDA: [A TeeParkots Inc Publishers Product]No ratings yet

- Jud AffDocument4 pagesJud AffYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- In God's Will, I Will Become A Lawyer. Pray, Study Hard and Everything Will Follow. Atty (.) Rhea L. DollisonDocument1 pageIn God's Will, I Will Become A Lawyer. Pray, Study Hard and Everything Will Follow. Atty (.) Rhea L. DollisonYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Breaking BadDocument3 pagesBreaking BadYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- VatDocument1 pageVatYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Penalties in GeneralDocument30 pagesPenalties in GeneralYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Buzzdock Ads: Kumonekta Sa Mga Kaibigan Online. Sumali Sa Grupong Facebook - Libre!Document3 pagesBuzzdock Ads: Kumonekta Sa Mga Kaibigan Online. Sumali Sa Grupong Facebook - Libre!Yan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Cus Tom KƏSTƏM/ : "The Old English Custom of Dancing Around The Maypole" Synonyms:, ,, ,, ,,, M OreDocument1 pageCus Tom KƏSTƏM/ : "The Old English Custom of Dancing Around The Maypole" Synonyms:, ,, ,, ,,, M OreYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Philippine Tariff FinderDocument1 pagePhilippine Tariff FinderYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Sanc Tion Sang (K) SH (Ə) NDocument2 pagesSanc Tion Sang (K) SH (Ə) NYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Construing Bigamy and Articles 40 and 41: What Went Wrong?Document13 pagesConstruing Bigamy and Articles 40 and 41: What Went Wrong?Yan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Levels of Organization: LEVEL 1 - CellsDocument2 pagesLevels of Organization: LEVEL 1 - CellsYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Cir Vs AlgueDocument2 pagesCir Vs AlgueYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Biology: For Other Uses, SeeDocument1 pageBiology: For Other Uses, SeeYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- For Other Uses, See and - This Article Is About A - For The Theory of Law, See - "Legal Concept" Redirects HereDocument2 pagesFor Other Uses, See and - This Article Is About A - For The Theory of Law, See - "Legal Concept" Redirects HereYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- GalaxyDocument1 pageGalaxyYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Ethics: (Eth-Iks) IPA SyllablesDocument1 pageEthics: (Eth-Iks) IPA SyllablesYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

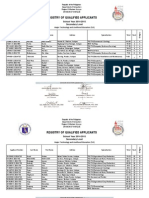

- Registry of Qualified Applicants: School Year 2014-2015 Secondary LevelDocument5 pagesRegistry of Qualified Applicants: School Year 2014-2015 Secondary LevelYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Filipino Drama in Japanese PeriodDocument1 pageFilipino Drama in Japanese PeriodYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

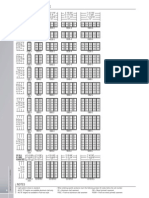

- Sizing Windows 400series Casement Casement AwningtransomDocument3 pagesSizing Windows 400series Casement Casement AwningtransomYan Lean Dollison100% (1)

- Del Rosario Vs FerrerDocument2 pagesDel Rosario Vs FerrerYan Lean Dollison100% (1)

- SPES 2015 Application FormDocument1 pageSPES 2015 Application FormYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Casement ElevationsDocument10 pagesCasement ElevationsYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- How To Evict A Live-In Girlfriend or Boyfriend - Combs Law Group, P.CDocument3 pagesHow To Evict A Live-In Girlfriend or Boyfriend - Combs Law Group, P.Cpujarze2No ratings yet

- Ab Initio or Is Rescindable by Reason of The Fraudulent Concealment orDocument2 pagesAb Initio or Is Rescindable by Reason of The Fraudulent Concealment orIldefonso HernaezNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Implication DigestsDocument12 pagesDoctrine of Implication DigestsHannah TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Bulger 4th Superseding IndictmentDocument93 pagesBulger 4th Superseding IndictmentWBURNo ratings yet

- Lakson Tobbaco Company 2008Document7 pagesLakson Tobbaco Company 2008Farqaleet KianiNo ratings yet

- 2 Corsiga vs. DefensorDocument5 pages2 Corsiga vs. Defensorchristopher d. balubayanNo ratings yet

- Is 2063 1 2002 PDFDocument75 pagesIs 2063 1 2002 PDFSuresh RajagopalNo ratings yet

- CIVIL LIBERTIES V EXECUTIVE SECRETARY G.R. No. 83896Document5 pagesCIVIL LIBERTIES V EXECUTIVE SECRETARY G.R. No. 83896Ariza ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Lepanto Consolidated Mining Co. v. Dumapis, G.R. No. 163210, (August 13, 2008), 584 PHIL 100-119Document10 pagesLepanto Consolidated Mining Co. v. Dumapis, G.R. No. 163210, (August 13, 2008), 584 PHIL 100-119Hershey Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- Court Order SSC Jen 2015 PDFDocument30 pagesCourt Order SSC Jen 2015 PDFPawan Kumar MeenaNo ratings yet

- Memorandum of Agreement - Relocation SurveyDocument4 pagesMemorandum of Agreement - Relocation Surveya.s.balilo01No ratings yet

- Unpaid Seller: A Seller Will Be Considered As An Unpaid Seller When He Satisfies Following ConditionsDocument5 pagesUnpaid Seller: A Seller Will Be Considered As An Unpaid Seller When He Satisfies Following ConditionskaranNo ratings yet

- Land TitsDocument56 pagesLand TitsKit ChampNo ratings yet

- Mark Weintraub v. United States, 400 U.S. 1014 (1971)Document5 pagesMark Weintraub v. United States, 400 U.S. 1014 (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- People V YabutDocument2 pagesPeople V YabutMark Leo BejeminoNo ratings yet

- Citibank CSRDocument3 pagesCitibank CSRJack JainNo ratings yet

- CRITICAL COMMENT ON RAGHUBAR SINGH VDocument16 pagesCRITICAL COMMENT ON RAGHUBAR SINGH VRitika RajawatNo ratings yet

- SITEL - Claims Reimbursement Form Rev.06 PDFDocument2 pagesSITEL - Claims Reimbursement Form Rev.06 PDFJoyce HerreraNo ratings yet

- Talisic v. Rinen PDFDocument3 pagesTalisic v. Rinen PDFRogelio BataclanNo ratings yet

- Lt. John Surface - Arrest Affidavit 2Document9 pagesLt. John Surface - Arrest Affidavit 2DavidNo ratings yet

- Ibt DB2Document3 pagesIbt DB2Ian TamondongNo ratings yet

- Enrique Caciedo Escobar v. U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, 935 F.2d 650, 4th Cir. (1991)Document7 pagesEnrique Caciedo Escobar v. U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, 935 F.2d 650, 4th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- REPORT OF SENATE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE (SPAC) ON THE ‘STATUS OF COMPLIANCE OF PARASTATALS’ SUBMISSION OF AUDITED ACCOUNTS AND AUDITOR’S REPORT THEREON TO THE OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR-GENERAL FOR THE FEDERATION’Document31 pagesREPORT OF SENATE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE (SPAC) ON THE ‘STATUS OF COMPLIANCE OF PARASTATALS’ SUBMISSION OF AUDITED ACCOUNTS AND AUDITOR’S REPORT THEREON TO THE OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR-GENERAL FOR THE FEDERATION’Olu Wole OnemolaNo ratings yet

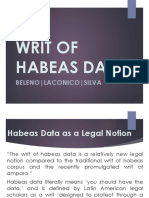

- Writ of Habeas DataDocument39 pagesWrit of Habeas DataMatthew WittNo ratings yet

- Pestle AnalysisDocument4 pagesPestle AnalysisKENNETH IAN MADERANo ratings yet

- Abad VS Dela Cruz 2015Document4 pagesAbad VS Dela Cruz 2015Lance ClementeNo ratings yet

- Independence of JudiciaryDocument6 pagesIndependence of JudiciaryChetan SharmaNo ratings yet

- LTD - Finals Quizzler - Answer Key (2019)Document5 pagesLTD - Finals Quizzler - Answer Key (2019)AndelueaNo ratings yet

Doctrine of Necessary Implication

Doctrine of Necessary Implication

Uploaded by

Yan Lean DollisonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Doctrine of Necessary Implication

Doctrine of Necessary Implication

Uploaded by

Yan Lean DollisonCopyright:

Available Formats

1. DOCTRINE OF NECESSARY IMPLICATION Chua vs. CSC and NIA [G.R. No. 88979.

. February 07, 1992] FACTS: Republic Act No. 6683 provided benefits for early retirement and voluntary separation from the government service as well as for involuntary separation due to reorganization. Deemed qualified to avail of its benefits are those enumerated in Sec. 2 of the Act. Petitioner Lydia Chua believing that she is qualified to avail of the benefits of the program, filed an application with respondent National Irrigation Administration (NIA) which, however, denied the same; instead, she was offered separation benefits equivalent to one half (1/2) month basic pay for every year of service commencing from 1980, or almost fifteen (15) years in four (4) successive governmental projects. A recourse by petitioner to the Civil Service Commission yielded negative results, citing that her position is co-terminous with the NIA project which is contractual in nature and thus excluded by the enumerations under Sec.3.1 of Joint DBM-CSC Circular Letter No. 89-1, i.e. casual, emergency, temporary or regular employment. Petitioner appealed to the Supreme Court by way of a special civil action for certiorari. ISSUE: Whether or not the petitioner is entitled to the benefits granted under Republic Act No. 6683. HELD: YES. Petition was granted. RATIO: Petitioner was established to be a co-terminous employee, a non-career civil servant, like casual and emergency employees. The Supreme Court sees no solid reason why the latter are extended benefits under the Early Retirement Law but the former are not. It will be noted that Rep. Act No. 6683 expressly extends its benefits for early retirement to regular, temporary, casual and emergency employees. But specifically excluded from the benefits are uniformed personnel of the AFP including those of the PC-INP. It can be argued that, expressio unius est exclusio alterius but the applicable maxim in this case is the doctrine of necessary implication which holds that what is implied in a statute is as much a part thereof as that which is expressed. [T]he Court believes, and so holds, that the denial by the respondents NIA and CSC of petitioners application for early retirement benefits under R.A. No. 6683 is unreasonable, unjustified, and oppressive, as petitioner had filed an application for voluntary retirement within a reasonable period and she is entitled to the benefits of said law. In the interest of substantial justice, her application must be granted; after all she served the government not only for two (2) years the minimum requirement under the law but for almost fifteen (15) years in four (4) successive governmental projects.

3. CHAPTER 12 MANDATORY AND DIRECTORY STATUTES Whether an enactment is mandatory or directory depends on the scope and the object of the statute. Where the enactment demands the performance of certain provision without any option or discretion itwill be called peremptory or mandatory. On the other hand if the acting authority is vested with discretion, choice or judgment the enactment is directory. In deciding whether the provision is directory or mandatory, one has to ascertain whether the power is coupled with a duty of the person to whom it is given to exercise it. If so, then it is imperative. Generally the intention of the legislature is expressed by mandatory and directory verbs such as may, shall and must. However, sometimes the legislature uses such words interchangeably. In such cases, the interpreter of the law has to consider the intention of the legislature. If two interpretations are possible then the one which preserves the constitutionality of the particular statutory provisions should be adopted and the one which renders it unconstitutional and void should be rejected. Non-compliance of mandatory provisions has penal consequences where as non-compliance of directory provisions would not furnish any cause of action or ground of challenge. Distinction .It is one of the rules of construction that a provision is not mandatory unless noncompliance with it is made penal. Mandatory provisions should be fulfilled and obeyed exactly, whereas in case of provisions of directory enactments substantial compliance is satisfiable. Test for determining whether a provision in a statute is directory or mandatory. Lord Campbell observed that there can be no universal applications as to when a statutory provisions be regarded as merely directory and when mandatory. The performance of certain provision without any option or discretion it will be called peremptory or mandatory. On the other hand if the acting authority is vested with discretion, choice or judgment the enactment is directory. In deciding whether the provision is directory or mandatory, one has to ascertain whether the power is coupled with a duty of the person to whom it is given to exercise it. If so, then it is imperative. Generally the intention of the legislature is expressed by mandatory and directory verbs such as may, shall and must. However, sometimes the legislature uses such words interchangeably. In such cases, the interpreter of the law has to consider the intention of the legislature. If two interpretations are possible then the one which preserves the constitutionality of the particular statutory provisions should be adopted and the one which renders it unconstitutional and void should be rejected. Non-compliance of mandatory provisions has penal consequences where as noncompliance of directory provisions would not furnish any cause of action or ground of challenge. Distinction It is one of the rules of construction that a provision is not mandatory unless non-compliance with it is made penal Mandatory provisions should be fulfilled and obeyed exactly, whereas in case of provisions of directory enactments substantial compliance is satisfiable. Test for determining whether a provision in a statute is directory or mandatory. Lord Campbell observed that there can be no universal applications as to when a statutory provisions be regarded as merely directory and when mandatory. Maxwell says that it is impossible to lay down any general rule for determining whether a provision is mandatory or directory. The supreme court of India is stressing time and again that the question whether a statute is mandatory or directory, is not capable of generalization and that in each case the

court should try and get at the real intention of the legislature by analyzing the entire provisions of the enactment and the scheme underlying it. In other words it depends on the intent of the legislature and not upon the language in which the intent is clothed. The intent of the legislature must be ascertained not only from the phraseology of the provision, but also from its nature, design and consequences which would follow from construing it in one form or another. May, shall and must. The words may, shall and must should initially be deemed to have been used in their natural and ordinary sense. May signifies permission and implies that the authority has been allowed discretion. In state of UP v Jogendra Singh, the Supreme Court observed that there is no doubt that the word may generally does not mean must or shall. But it is well settled that the word may is capable of meaning must or shall in the light of context. It is also clear that when a discretion is conferred upon a public authority coupled with an obligation, the word may should be construed to mean a command ( Smt. Sudir Bala Roy v West Bengal). May will have compulsory force if a requisite condition has to be filled. Cotton L.J observed that May can never mean must but when any authority or body has a power to it by the word May it becomes its duty to exercise that power. Shall- in the normal sense imports command. It is well settled that the use of the word shall does not always mean that the enactment is obligatory or mandatory. It depends upon the context in which the word shall occurs and the other circumstances. Unless an interpretation leads to some absurd or inconvenient consequences or contradicts with the intent of the legislature the court shall interpret the word shall in mandatory sense. Must- is doubtlessly a word of command. Specific Terminologies 99% of negative terms are mandatory; affirmative terms are mostly mandatory where guiding principle for vesting of powers depends on context. In procedural statutes both negative and affirmative are mandatory. Aids to construction for determination of the character of words can be used. Time fixation If time fixation is provided to the executive, it is supposed to be permissive with regard to the issue of time only. However, provisions regarding time may be considered mandatory if the intention of the legislature appears to impose literal compliance with the requirement of time. Statutes regulating tax and election proceeding are generally considered permissive. However the Supreme Court held in Manila mohan lal v Syed Ahamed, whenever a statute requires a particular act to be done in a particular manner and also lays down that failure to comply will have consequence. It would be difficult to accept the argument that the failure to comply with the required said requirement should lead to any other consequence.

You might also like

- Cot 1 Lesson Plan Freedom of The Human PersonDocument13 pagesCot 1 Lesson Plan Freedom of The Human PersonJohn Eric Peregrino86% (14)

- Statcon NotesDocument35 pagesStatcon NotesAliNo ratings yet

- StatCon Finals ReviewerDocument13 pagesStatCon Finals ReviewerEmman Cariño100% (2)

- Privatization and Management Office v. Strategic Alliance Development CorporationDocument2 pagesPrivatization and Management Office v. Strategic Alliance Development CorporationJaypee Ortiz67% (3)

- Speech Chart of CasesDocument10 pagesSpeech Chart of CasesusflawstudentNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Necessary ImplicationDocument19 pagesDoctrine of Necessary ImplicationAivy Christine Manigos100% (1)

- Presumptions in StatconDocument40 pagesPresumptions in StatconNicole Deocaris100% (1)

- Presumptions STATCON ReportDocument13 pagesPresumptions STATCON ReportAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAANo ratings yet

- Palanca v. City of Manila and TrinidadDocument2 pagesPalanca v. City of Manila and TrinidadJanine Ismael100% (1)

- Ang Yu VS CaDocument2 pagesAng Yu VS Cairene anibongNo ratings yet

- Ting Vs Velez-TingDocument4 pagesTing Vs Velez-TingPaolo Mendioro100% (2)

- Obligations and Contracts Case Updates 2005 2014 2doc PDFDocument107 pagesObligations and Contracts Case Updates 2005 2014 2doc PDFNufa AlyhaNo ratings yet

- Exam ConstiDocument11 pagesExam ConstiAngie DouglasNo ratings yet

- Chrea Vs CHR Case DigestDocument6 pagesChrea Vs CHR Case DigestAj Guadalupe de MataNo ratings yet

- Stacon Case DigestDocument5 pagesStacon Case DigestRICKY ALEGARBESNo ratings yet

- How To Do A Case DigestDocument2 pagesHow To Do A Case DigestHK FreeNo ratings yet

- US V HartDocument2 pagesUS V HartJerahmeel CuevasNo ratings yet

- Ferrer V Bautista DigestDocument6 pagesFerrer V Bautista DigestJamiah HulipasNo ratings yet

- Obligations and Contracts Case Updates (2005-2014)Document88 pagesObligations and Contracts Case Updates (2005-2014)starryarryNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law: 1987 Constitution of The Republic of The PhilippinesDocument44 pagesConstitutional Law: 1987 Constitution of The Republic of The PhilippinesimoymitoNo ratings yet

- Calalang Vs Williams (Digest)Document1 pageCalalang Vs Williams (Digest)Stefan SalvatorNo ratings yet

- Crimpro ReviewerDocument59 pagesCrimpro ReviewerjojitusNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument25 pagesCase DigestDendi roszellsexy100% (1)

- Doctrine of Necessary ImplicationDocument1 pageDoctrine of Necessary Implicationprime100% (2)

- Political SBCDocument94 pagesPolitical SBCMDNo ratings yet

- Table of Contents Case DigestDocument9 pagesTable of Contents Case DigestBiggie DesturaNo ratings yet

- Facts:: 109. NPC V SPSDocument1 pageFacts:: 109. NPC V SPSLuna BaciNo ratings yet

- Consti Final ExamDocument39 pagesConsti Final ExamVeen Galicinao FernandezNo ratings yet

- Enrique Abad Vs Goldloop DigestDocument1 pageEnrique Abad Vs Goldloop DigestRyan Suaverdez100% (3)

- StatCon - Syllabus 2018Document13 pagesStatCon - Syllabus 2018Josiah BalgosNo ratings yet

- What Is A Breach of Promise To MarryDocument2 pagesWhat Is A Breach of Promise To MarryThina ChiiNo ratings yet

- Stat Con NotesDocument6 pagesStat Con NotesMis DeeNo ratings yet

- Summary of Manila Prince Hotel V GSISDocument3 pagesSummary of Manila Prince Hotel V GSISEros CabauatanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 - Judicial DepartmentDocument18 pagesChapter 12 - Judicial Departmentrizumu00No ratings yet

- Nitafan V Cir 152 Scra 284Document7 pagesNitafan V Cir 152 Scra 284Anonymous K286lBXothNo ratings yet

- Basic Guidelines PDFDocument3 pagesBasic Guidelines PDFSrezon HalderNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7 - Maxims, Doctrines, Rules and Interpretation of The LawsDocument8 pagesChapter 7 - Maxims, Doctrines, Rules and Interpretation of The LawsVanessa Alarcon100% (2)

- Statcon Cases 7-12Document8 pagesStatcon Cases 7-12Frances Grace DamazoNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Implication DigestsDocument12 pagesDoctrine of Implication DigestsHannah TolentinoNo ratings yet

- STATCON Group 2 Legal MaximsDocument15 pagesSTATCON Group 2 Legal Maximsangelyn susonNo ratings yet

- Revalida Question 10Document2 pagesRevalida Question 10Kyle BanceNo ratings yet

- Term Paper in Statutory ConstructionDocument17 pagesTerm Paper in Statutory ConstructionMichelle VillamoraNo ratings yet

- MagdaDocument24 pagesMagdaIco AtienzaNo ratings yet

- Landbank of The Philippines vs. SantosDocument25 pagesLandbank of The Philippines vs. SantosTia RicafortNo ratings yet

- Case Name Metrobank V RosalesDocument2 pagesCase Name Metrobank V RosalesMowie AngelesNo ratings yet

- BOCEA vs. Teves Case DigestDocument2 pagesBOCEA vs. Teves Case DigestRhodz Coyoca Embalsado100% (1)

- Case No. 29 People v. Pimentel 288 SCRA 542 (1998)Document1 pageCase No. 29 People v. Pimentel 288 SCRA 542 (1998)William Christian Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-51201 May 29, 1980Document6 pagesG.R. No. L-51201 May 29, 1980Amrosy Bani BunsaNo ratings yet

- Statutory Construction and InterpretationDocument9 pagesStatutory Construction and InterpretationMichael Angelo Victoriano100% (1)

- Statcon FinalsDocument5 pagesStatcon FinalsChami PanlaqueNo ratings yet

- CIR V PRIMETOWN PROPERTY G.R. No. 162155Document3 pagesCIR V PRIMETOWN PROPERTY G.R. No. 162155Ariza Valencia100% (1)

- Republic vs. Court of Appeals (299 SCRA 199)Document4 pagesRepublic vs. Court of Appeals (299 SCRA 199)Krisleen Abrenica50% (2)

- Chua Case Spec. Pro.Document1 pageChua Case Spec. Pro.Donny WalshNo ratings yet

- Adasa v. Abalos (G.R. No. 168617)Document5 pagesAdasa v. Abalos (G.R. No. 168617)Rache Gutierrez100% (1)

- Mandatory and Directory StatutesDocument23 pagesMandatory and Directory StatutesSabir Saif Ali ChistiNo ratings yet

- Mandatory and Directory StatutesDocument23 pagesMandatory and Directory StatutesLoolu Kutty50% (2)

- Mandatory and Directory ProvisionsDocument5 pagesMandatory and Directory ProvisionsSUBRAHMANYA BHATNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 IosDocument34 pagesUnit 1 IosJibin KozhikkottuNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of Mandatory and Directory Statutes: Presented By: Rinkey Sharma Asst. Prof. of Law IilsDocument18 pagesInterpretation of Mandatory and Directory Statutes: Presented By: Rinkey Sharma Asst. Prof. of Law Iilsvenkatesha conapalliNo ratings yet

- Himmat Lal K Shah v. Commissioner of PoliceDocument6 pagesHimmat Lal K Shah v. Commissioner of PoliceSom Dutt VyasNo ratings yet

- Basic Principles of InterpretationDocument8 pagesBasic Principles of Interpretationangel mathewNo ratings yet

- THE LABOUR LAW IN UGANDA: [A TeeParkots Inc Publishers Product]From EverandTHE LABOUR LAW IN UGANDA: [A TeeParkots Inc Publishers Product]No ratings yet

- Jud AffDocument4 pagesJud AffYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- In God's Will, I Will Become A Lawyer. Pray, Study Hard and Everything Will Follow. Atty (.) Rhea L. DollisonDocument1 pageIn God's Will, I Will Become A Lawyer. Pray, Study Hard and Everything Will Follow. Atty (.) Rhea L. DollisonYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Breaking BadDocument3 pagesBreaking BadYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- VatDocument1 pageVatYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Penalties in GeneralDocument30 pagesPenalties in GeneralYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Buzzdock Ads: Kumonekta Sa Mga Kaibigan Online. Sumali Sa Grupong Facebook - Libre!Document3 pagesBuzzdock Ads: Kumonekta Sa Mga Kaibigan Online. Sumali Sa Grupong Facebook - Libre!Yan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Cus Tom KƏSTƏM/ : "The Old English Custom of Dancing Around The Maypole" Synonyms:, ,, ,, ,,, M OreDocument1 pageCus Tom KƏSTƏM/ : "The Old English Custom of Dancing Around The Maypole" Synonyms:, ,, ,, ,,, M OreYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Philippine Tariff FinderDocument1 pagePhilippine Tariff FinderYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Sanc Tion Sang (K) SH (Ə) NDocument2 pagesSanc Tion Sang (K) SH (Ə) NYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Construing Bigamy and Articles 40 and 41: What Went Wrong?Document13 pagesConstruing Bigamy and Articles 40 and 41: What Went Wrong?Yan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Levels of Organization: LEVEL 1 - CellsDocument2 pagesLevels of Organization: LEVEL 1 - CellsYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Cir Vs AlgueDocument2 pagesCir Vs AlgueYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Biology: For Other Uses, SeeDocument1 pageBiology: For Other Uses, SeeYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- For Other Uses, See and - This Article Is About A - For The Theory of Law, See - "Legal Concept" Redirects HereDocument2 pagesFor Other Uses, See and - This Article Is About A - For The Theory of Law, See - "Legal Concept" Redirects HereYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- GalaxyDocument1 pageGalaxyYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Ethics: (Eth-Iks) IPA SyllablesDocument1 pageEthics: (Eth-Iks) IPA SyllablesYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Registry of Qualified Applicants: School Year 2014-2015 Secondary LevelDocument5 pagesRegistry of Qualified Applicants: School Year 2014-2015 Secondary LevelYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Filipino Drama in Japanese PeriodDocument1 pageFilipino Drama in Japanese PeriodYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Sizing Windows 400series Casement Casement AwningtransomDocument3 pagesSizing Windows 400series Casement Casement AwningtransomYan Lean Dollison100% (1)

- Del Rosario Vs FerrerDocument2 pagesDel Rosario Vs FerrerYan Lean Dollison100% (1)

- SPES 2015 Application FormDocument1 pageSPES 2015 Application FormYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Casement ElevationsDocument10 pagesCasement ElevationsYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- How To Evict A Live-In Girlfriend or Boyfriend - Combs Law Group, P.CDocument3 pagesHow To Evict A Live-In Girlfriend or Boyfriend - Combs Law Group, P.Cpujarze2No ratings yet

- Ab Initio or Is Rescindable by Reason of The Fraudulent Concealment orDocument2 pagesAb Initio or Is Rescindable by Reason of The Fraudulent Concealment orIldefonso HernaezNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Implication DigestsDocument12 pagesDoctrine of Implication DigestsHannah TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Bulger 4th Superseding IndictmentDocument93 pagesBulger 4th Superseding IndictmentWBURNo ratings yet

- Lakson Tobbaco Company 2008Document7 pagesLakson Tobbaco Company 2008Farqaleet KianiNo ratings yet

- 2 Corsiga vs. DefensorDocument5 pages2 Corsiga vs. Defensorchristopher d. balubayanNo ratings yet

- Is 2063 1 2002 PDFDocument75 pagesIs 2063 1 2002 PDFSuresh RajagopalNo ratings yet

- CIVIL LIBERTIES V EXECUTIVE SECRETARY G.R. No. 83896Document5 pagesCIVIL LIBERTIES V EXECUTIVE SECRETARY G.R. No. 83896Ariza ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Lepanto Consolidated Mining Co. v. Dumapis, G.R. No. 163210, (August 13, 2008), 584 PHIL 100-119Document10 pagesLepanto Consolidated Mining Co. v. Dumapis, G.R. No. 163210, (August 13, 2008), 584 PHIL 100-119Hershey Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- Court Order SSC Jen 2015 PDFDocument30 pagesCourt Order SSC Jen 2015 PDFPawan Kumar MeenaNo ratings yet

- Memorandum of Agreement - Relocation SurveyDocument4 pagesMemorandum of Agreement - Relocation Surveya.s.balilo01No ratings yet

- Unpaid Seller: A Seller Will Be Considered As An Unpaid Seller When He Satisfies Following ConditionsDocument5 pagesUnpaid Seller: A Seller Will Be Considered As An Unpaid Seller When He Satisfies Following ConditionskaranNo ratings yet

- Land TitsDocument56 pagesLand TitsKit ChampNo ratings yet

- Mark Weintraub v. United States, 400 U.S. 1014 (1971)Document5 pagesMark Weintraub v. United States, 400 U.S. 1014 (1971)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- People V YabutDocument2 pagesPeople V YabutMark Leo BejeminoNo ratings yet

- Citibank CSRDocument3 pagesCitibank CSRJack JainNo ratings yet

- CRITICAL COMMENT ON RAGHUBAR SINGH VDocument16 pagesCRITICAL COMMENT ON RAGHUBAR SINGH VRitika RajawatNo ratings yet

- SITEL - Claims Reimbursement Form Rev.06 PDFDocument2 pagesSITEL - Claims Reimbursement Form Rev.06 PDFJoyce HerreraNo ratings yet

- Talisic v. Rinen PDFDocument3 pagesTalisic v. Rinen PDFRogelio BataclanNo ratings yet

- Lt. John Surface - Arrest Affidavit 2Document9 pagesLt. John Surface - Arrest Affidavit 2DavidNo ratings yet

- Ibt DB2Document3 pagesIbt DB2Ian TamondongNo ratings yet

- Enrique Caciedo Escobar v. U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, 935 F.2d 650, 4th Cir. (1991)Document7 pagesEnrique Caciedo Escobar v. U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service, 935 F.2d 650, 4th Cir. (1991)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- REPORT OF SENATE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE (SPAC) ON THE ‘STATUS OF COMPLIANCE OF PARASTATALS’ SUBMISSION OF AUDITED ACCOUNTS AND AUDITOR’S REPORT THEREON TO THE OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR-GENERAL FOR THE FEDERATION’Document31 pagesREPORT OF SENATE PUBLIC ACCOUNTS COMMITTEE (SPAC) ON THE ‘STATUS OF COMPLIANCE OF PARASTATALS’ SUBMISSION OF AUDITED ACCOUNTS AND AUDITOR’S REPORT THEREON TO THE OFFICE OF THE AUDITOR-GENERAL FOR THE FEDERATION’Olu Wole OnemolaNo ratings yet

- Writ of Habeas DataDocument39 pagesWrit of Habeas DataMatthew WittNo ratings yet

- Pestle AnalysisDocument4 pagesPestle AnalysisKENNETH IAN MADERANo ratings yet

- Abad VS Dela Cruz 2015Document4 pagesAbad VS Dela Cruz 2015Lance ClementeNo ratings yet

- Independence of JudiciaryDocument6 pagesIndependence of JudiciaryChetan SharmaNo ratings yet

- LTD - Finals Quizzler - Answer Key (2019)Document5 pagesLTD - Finals Quizzler - Answer Key (2019)AndelueaNo ratings yet

![THE LABOUR LAW IN UGANDA: [A TeeParkots Inc Publishers Product]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/702714789/149x198/ac277f344e/1706724197?v=1)