Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Temprory Injuction

Temprory Injuction

Uploaded by

Abha KumariOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Temprory Injuction

Temprory Injuction

Uploaded by

Abha KumariCopyright:

Available Formats

introduction The law of injunction in India has its origin in the Equity Jurisprudence of England from which we have

inherited the present administration of law. England too in its turn borrowed it from the Roman Law wherein it was known as Interdict. The Roman Interdicts were divided in three parts, prohibitory, restitutory and exhibitory. The prohibitory Interdict corresponds to injunction. The injunction as a chancery remedy developed at the time of Henry, the Vlth. The Chancellor set aside a certain bond by the plaintiff as one not binding on him. The Court of Common Pleas, however, gave a decree with bond. Chancellor thereupon devised the remedy of injunction by which he prohibited execution of the decree of Common Law Court. This exercise of power by issuing injunction by the Chancery Court was viewed with jealousy by the Common Law Court and it became a source of conflict between the two jurisdictions. This conflict rose to the climax between the Lord Justice Coke and Lord Chancellor Ellesmere in 1816. A decree was obtained from Lord Coke by practising gross fraud. The Chancellor thereupon by an injunction perpetually enjoined the decree-holder from proceeding to execute his judgment. The validity of this procedure of issuing injunction was seriously questioned. The matter was referred to Bacon, the then Attorney General and other counsel, who finally settled the question in favour of Chancellor. The jurisdiction to issue injunctions was thus affirmed and the remedy which is termed as the strong arm of the Courts of equity has contributed a lot to consolidate the position of the judiciary in dispensing justice between the litigant parties. From the aforesaid historical background it is manifest that the origin of the power to grant injunction is from equity, hence the exercise of the discretion by the Courts is to be governed mainly by equitable considerations. In our country in Criminal matters Sections 133, 142 and 144 of the Code of Criminal Procedure deal with grant of injunction. In Civil matters the law relating to grant of injunction is contained in Chapter VII of Part III of the Specific Relief Act, 1963. Sections 36 to 42 deal with the grant of injunction. It has been termed as a prever1tive relief which is granted at the discretion of the Court by injunction which may be temporary or perpetual. Section 37(1) and section 53 of the Specific Relief Act, 1963 deals with the temporary injunctions which are such as are to continue until a specified time, or until further orders of the Court, In CPC it is found in Sections 94(c) and Order 39 Rule 1 to5

TEMPORARY INJUNCTION

Every court is constituted for the purpose of administering justice between the parties and therefore, must be deemed to process all such powers as may be necessary to do full and complete justice to the parties before it. So far as the grant of temporary injunctions Is concerned, it used to be a small step during the progress of the suit or proceeding towards the preservation of its subject matter which could be property or any other right has now gained enormous importance and sometimes it becomes even more important than the final result of the suit or proceedings with the change of the time It is a well stated principle of law that an interim relief can always be granted in the aid of and as ancillary to the main relief available to the party on final determination of his rights in a suit or any other proceeding therefore, a court undoubtedly processes the power to grant interim relief during the pendency of the suit.

Case: State of Orissa vs. Madan Gopal, AIR (1952) An injunction is a judicial process whereby a party is required to do or to refrain from doing any particular act. Temporary injunction is mode of granting preventive relief by the court at its discretion. A temporary injunction is also known as interim injunction.

Object of temporary injunction

The purpose of granting interim relief is the preservation of property in dispute till legal rights and conflicting claims of the parties before the court are adjudicated.

The underlying object of granting temporary injunction is to maintain and preserve status quo at the time of institution of the proceedings and to prevent any change in it until the final determination of the suit.

Definition: According to order 39 of the CPC any order made temporarily prohibiting the defendant not to alienate, or to change or to damage the property in dispute during the pendency of the suit is called temporary injunction.

According to section 37(1) of the S. R. Act, temporary injunctions are such as are to continue until a specified time, or until the further order of the Court. They may be granted at any period of a suit and are regulated by the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908.

Thus temporary injunction is regulated under the provisions of rules 1-5, order 39 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 Temporary Injunction in Civil Procedure Code Section 94 (c) and (e) of Code of Civil Procedure contain provisions under which the Court may in order to prevent the ends of justice from being defeated, grant a temporary injunction or make such other interlocutory order as may appear to the Court to be just and convenient. Section 95 further provides that where in any suit a temporary injunction is granted and it appears to the Court that there were no sufficient grounds, or the suit of the plaintiff falls and it appears to the Court that there was no reasonable or probable ground for instituting the same. The Court may on application of the defendant award reasonable compensation which may be to the extent of the pecuniary Jurisdiction of the Court trying the suit. The procedure with regard to the grant of temporary injunction and interlocutory orders has been provided in Order 39 of C.P.C., as far as this State is concerned, drastic changes were brought about by

amending the provisions contained in Order 39 by U.P. Act No. 57 of 1976. In Sub-Rule (2) of Rule 2 of Order 39, a proviso was inserted by which power of the Court to grant injunction was taken away in certain matters. Further a proviso was added in Rule 3 which provided that where it is proposed to grant an injunction without giving notice of the application to the opposite party, the Court shall record the reasons for its opinion that the object of granting the injunction would be defeated by the delay and require the applicant to serve the copy of the order of injunction along with copy of the application, affidavit, plaint and other documents relied on by him. Further, he has also been required to file on the same day on which the injunction is granted, an affidavit stating that the requirements contained in Proviso (a) have been complied with. Rule 3(e) further contains a very important provision which requires the Court to make an endeavour to finally dispose of the application within 30 days from the date on which the Injunction was granted and where it is unable to do so it shall record its reasons for such inability. Thus by introducing the aforesaid amendment an attempt was made to minimise the hardship and harassment caused by the injunction orders passed exparte.

When and how a temporary injunction is granted Grounds: According to Order 39 Rules 1& 2 of the CPC Temporary injunction may be granted by the Court in the following cases Where in any suit it is proved by affidavit or otherwiseI. Where any property in dispute in a suit is in danger of being wasted, damaged or alienated by any party to the suit, or wrongfully sold in execution of a decree or

II.

where the defendants threatens, or intends to remove or dispose of his property with a view to defrauding his creditors; or

III.

where the defendants threatens to dispossess the plaintiff or otherwise cause injury to the plaintiff in relation to any property in dispute in the suit; or

IV.

Where the defendant is about to commit a breach of contract, or other injury of any kind;

V.

Where the court is of the opinion that the interest of justice so requires.

Other basic condition The power to grant temporary injunction is in the discretion of the Court. This discretion however should be exercised reasonably, judiciously and on sound legal principles. Before granting a temporary injunction, the court must consider the following principles:-(i) When an application is made for it (ii) When the court is satisfied about the following aspects; namely(a) prima facie case (b) Irreparable loss (c) Balance of convenience; and (iii) After the notice has been given to the opposite (Rule 3, Order 39)

In granting a temporary injunction the Court should consider, Firstly- The plaintiff makes out a prima facie case; Secondly- That the plaintiff will suffer irreparable loss if the injunction prayed for is not granted; and Thirdly- The balance of convenience lies in favour of the plaintiff. In Dalpat Kumar & Anr. Vs. Prahlad Singh & Ors., AIR 1993 SC 276, the Supreme Court explained the scope of aforesaid material circumstances, but observed as under:- The

phrases `prima facie case, `balance of convenience and ` irreparable loss are not rhetoric phrases for incantation, but words of width and elasticity, to meet myriad situations presented by mans ingenuity in given facts and circumstances, but always is hedged with sound exercise of judicial discretion to meet the ends of justice. The facts rest eloquent and speak for themselves. It is well nigh impossible to find from facts prima facie case and balance of convenience.

Case: MT. AymumNessa vs. md. Obaidul haque, 35 DLR Temporary injunction should be refused in the absence of the above mentioned three principles. In Nawab Mir Barkat Ali vs. Nawab Zulfiquar AIR 1982 A.P. 384, the court held that the petitioner shall (i) make out "prima facie" case (ii) show that balance of convenience is in his favour and (iii) show that he would suffer irreparable loss if temporary injunction is not granted in his favour. Further, the first condition being "sine qua non", the plaintiff must prove one of the remaining two conditions for grant of temporary injunction.

Prima facie case: At first the court must consider whether the plaintiff makes out of a prima facie case in support of his claim. The existence of a prima facie case in favour of the plaintiff is necessary before a temporary injunction can be granted to him. Good prima facie case has been explained to mean that a serious question is to be tried in the suit and in the event of success, if the injunction be not granted the plaintiff would suffer irreparable injury. Cases: Uttara Bank vs. Macneill & Kilburn Ltd. 33 DLR.

The burden is on the plaintiff to satisfy the court by leading evidence or otherwise that he has a prima facie case in his favour of him. In respect of prima facie case, it was held in K. Karunanidhi vs. R. Ranganathan Chettiar AIR 1973 Mad 443 that prima facie case does not mean the thorough examination of the rival claims by the court. This is so because the scope of enquiry in an interlocutory application like a petition for temporary injunction is limited and not exhaustive as in the case of a suit. It was observed in M.K. Dasappa vs. G. Ramachandra: AIR 1976 Kant. 53 that in deciding prima facie case the court is to be guided by the apparent strength or otherwise of plaintiffs case as revealed in the affidavits or other material. In Deity Kashiswar Mahadev vs. Gram Sabha: AIR 1973 H.P. 2, the court pointed out that the plaintiff need not prove his title to the property in temporary injunction petition and that it is enough if the plaintiff can show that he has a fair question to raise as to existence of right of which he alleges and can satisfy the court that the property in dispute should be preserved in its present actual condition until such question is disposed of. Explaining the ambit and the scope of the connotation prima facie case inMartin Burn Ltd. VS. Banerjee 1958. A prima facie case does not mean a case proved to the hilt but a case which can be said to be established if the evidence which is led in support of the same were believed.

Irreparable injury: Irreparable injury means that the injury must be one that cannot be adequately compensated for in damages. The mere fact that if no injunctins was granted the party would be open to criminal prosecution does not mean that irreparable injury would be non issue of an injunction. The existence of a prima facie case is not itself sufficient. The applicant should further show that irreparable injury will occur to him if the injunction is not granted and there is no other remedy open to him by which he will protect himself from the consequences of the apprehended injury. PLD 1960 Dhaka, 153 (DB)

In the case of Orissa State Commercial Transport Corporation Ltd. v. Satyanarayan Singh, (1974) 40 Cut LT 336, observed: 'Irreparable injury' means such injury which cannot be adequately remedied by damages. (The Supreme Court in Hindustan Petroleum Corporation v. Shrinarayan and Ors., (2002) 5 SCC 760, has held with regard to grant of interlocutory injunction which can also be applied with regard to grant of permanent injunction. It is specifically clear from the above principle that with regard to grant of permanent injunction the Court has to see that whether plaintiff has a legal right asserted by him in his favour or by violation of his right he would suffer irreparable injury

Balance of inconvenience: The court should issue an injunction where the balance of convenience is in favour of the plaintiff and not where the balance is in favour of the opposite party. The meaning of balance of convenience in favour of the plaintiff is that if an injunction is not granted and the suit is ultimately decided in favour of the plaintiffs. The inconvenience caused to the plaintiff would be granted than that which would be caused to the defendants if an injunction is grated but the suit is ultimately dismissed. Although it is called balance of convenience it is really the balance of inconvenience, and it is for the plaintiffs to show that the inconvenience caused to them would be granted than that which may be caused to the defendants. Should the inconvenience be equal, it is the plaintiffs who suffer. In other wards the plaintiffs have to show that the comparative mischief from the inconvenience which is likely to arise from withholding the injunction will be greater than which is likely to arise from granting it. In Bikash Chandra Deb vs Vijaya Minerals Pvt. Ltd.: 2005 (1) CHN 582, the Honble Calcutta High Court observed that issue of balance of convenience, it is to be noted that the Court shall lean in favour of introduction of the concept of balance of convenience, but does not mean and imply that the balance would be on one side and not in favour of the other. There must be proper balance between the parties and the balance cannot be an one-sided affair. in Antaryami Dalabehera vs Bishnu Charan Dalabehera: 2002 I OLR 531, as this point, it was held that balance of convenience, which means, comparative mischief for inconvenience to

the parties. The inconvenience to the petitioner if temporary Injunction is refused would be balanced and compared with that of the opposite party, if it is granted. In Anwar Elahi vs Vinod Misra And Anr. 1995 IVAD Delhi 576, 60 (1995) DLT 752, 1995 (35) DRJ 341 it was held that Balance of convenience means that comparative mischief or inconvenience which is likely to issue from withholding the injunction will be greater than that which is likely to arise from granting it. In applying this principle, the Court has to weigh the amount of substantial mischief that is likely to be done to the applicant if the injunction is refused and compare it with that which is likely to be caused to the other side if the injunction is granted. In Colgate Palmolive (India) Ltd. Vs. Hindustan Lever Ltd., AIR 1999 SC 3105, this court observed that the other considerations which ought to weigh with the Court hearing the application or petition for the grant of injunctions are as below : (i) Extent of damages being an adequate remedy; (ii) Protect the plaintiffs interest for violation of his rights though however having regard to the injury that may be suffered by the defendants by reason therefor ; (iii) The court while dealing with the matter ought not to ignore the factum of strength of one partys case being stronger than the others; (iv) No fixed rules or notions ought to be had in the matter of grant of injunction but on the facts and circumstances of each case- the relief being kept flexible; (v) The issue is to be looked from the point of view as to whether on refusal of the injunction the plaintiff would suffer irreparable loss and injury keeping in view the strength of the parties case; (vi) Balance of convenience or inconvenience ought to be considered as an important requirement even if there is a serious question or prima facie case in support of the grant; (vii) Whether the grant or refusal of injunction will adversely affect the interest of general public which can or cannot be compensated otherwise.

You might also like

- Challenge of Jurisdiction Layout1Document7 pagesChallenge of Jurisdiction Layout1Michael Kovach99% (71)

- IN 441 Case Principles SP 2019Document2 pagesIN 441 Case Principles SP 2019Ghina Shaikh100% (1)

- Stan Allen Urbanisms in The Plural The Information ThreadDocument26 pagesStan Allen Urbanisms in The Plural The Information ThreadAneta Mudronja PletenacNo ratings yet

- Introduction To MootingDocument12 pagesIntroduction To MootingPrakash KumarNo ratings yet

- Summary SuitsDocument18 pagesSummary SuitsRajendra KumarNo ratings yet

- Temporary InjunctionDocument6 pagesTemporary InjunctionBasant Kamboj100% (2)

- TPA (Lis Pedence & Part Perfm.)Document5 pagesTPA (Lis Pedence & Part Perfm.)Unknown100% (1)

- Long Questions & Answers: Law of PropertyDocument30 pagesLong Questions & Answers: Law of PropertyASHISH LOYANo ratings yet

- The Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 Non-Joinder and Misjoinder Parties To SuitsDocument13 pagesThe Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 Non-Joinder and Misjoinder Parties To Suitsnirav doshiNo ratings yet

- Evidence ActDocument23 pagesEvidence ActsandliNo ratings yet

- Burden & Standard of ProofDocument8 pagesBurden & Standard of ProofDickson Tk Chuma Jr.No ratings yet

- Jurisdiction in International Law - Details You Must Know - IpleadersDocument14 pagesJurisdiction in International Law - Details You Must Know - IpleadersSakshi JhaNo ratings yet

- Dying DeclarationsDocument3 pagesDying DeclarationszmblNo ratings yet

- Substance and ProcedureDocument20 pagesSubstance and ProcedureAditya GuptaNo ratings yet

- Arrest Under CRPCDocument5 pagesArrest Under CRPCMSSLLB1922 SuryaNo ratings yet

- Writ JurisdictionDocument3 pagesWrit JurisdictionRS123No ratings yet

- AsylumDocument4 pagesAsylummehak khanNo ratings yet

- JURISDICTIONDocument15 pagesJURISDICTIONPuneet BhushanNo ratings yet

- ProhibtionDocument4 pagesProhibtionshaina batraNo ratings yet

- A. Preventive Relief: 1. INJUNCTIONS (O. 29 RHC 2012)Document16 pagesA. Preventive Relief: 1. INJUNCTIONS (O. 29 RHC 2012)syakirahNo ratings yet

- SummonsDocument11 pagesSummonsjuhanaoberoiNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of RestitutionDocument15 pagesDoctrine of RestitutionBhart BhardwajNo ratings yet

- Media Law: Contempt of CourtDocument15 pagesMedia Law: Contempt of CourtKimmy May Codilla-AmadNo ratings yet

- Pre-Trial Stage in Criminal LawDocument9 pagesPre-Trial Stage in Criminal LawSunil DahiyaNo ratings yet

- 7.law of TreatiesDocument11 pages7.law of TreatiesAleePandoSolano100% (1)

- TRESPASSDocument46 pagesTRESPASSTilakNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Law of TortsDocument15 pagesIntroduction To The Law of TortssrinivasaNo ratings yet

- Analyzing Preventive Detention in Light of Constitutional ProvisionsDocument20 pagesAnalyzing Preventive Detention in Light of Constitutional ProvisionsRahul TambiNo ratings yet

- Banking Laws Non Performing Assets A Study of Legal RegulationsDocument26 pagesBanking Laws Non Performing Assets A Study of Legal Regulationssandhya raniNo ratings yet

- International Crimes Tribunal (ICTB) Bangladesh and Violations of Right To Fair Trial A Comparative StudyDocument16 pagesInternational Crimes Tribunal (ICTB) Bangladesh and Violations of Right To Fair Trial A Comparative StudyMuhammad Abdullah Fazi100% (2)

- Sovereignty and International LawDocument6 pagesSovereignty and International LawAkshatNo ratings yet

- Advisory Jurisdiction of Supreme CourtDocument49 pagesAdvisory Jurisdiction of Supreme CourtMohammad Imran0% (1)

- Asylum - International LawDocument18 pagesAsylum - International LawGulka TandonNo ratings yet

- My Research ProposalDocument7 pagesMy Research ProposalSumeda AriyaratneNo ratings yet

- 3.enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards Issues and Challenges PDFDocument42 pages3.enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards Issues and Challenges PDFPintu BabuNo ratings yet

- AbdmentDocument23 pagesAbdmentmilindaNo ratings yet

- Pil ProjectDocument21 pagesPil ProjectMahamana Malaviya NYPNo ratings yet

- Judicial Internship Experience by Tejas ParabDocument3 pagesJudicial Internship Experience by Tejas ParabAdv Tejas Parab100% (1)

- Section 57 of The Indian Evidence ActDocument4 pagesSection 57 of The Indian Evidence ActActusReusJurorNo ratings yet

- LLB 5TH Sem CPC Unit 3Document15 pagesLLB 5TH Sem CPC Unit 3Duby ManNo ratings yet

- Special Rules of EvidenceDocument2 pagesSpecial Rules of EvidenceZeesahnNo ratings yet

- Practice Note: Competence and Compellability of WitnessesDocument3 pagesPractice Note: Competence and Compellability of WitnessesMERCY LAWNo ratings yet

- Act 29 (Mensah B Annotated)Document198 pagesAct 29 (Mensah B Annotated)Emmanuella KwatiaNo ratings yet

- Limitation ActDocument28 pagesLimitation ActHuzefa Mannan DohadwalaNo ratings yet

- Law of EvidenceDocument14 pagesLaw of EvidenceSuhani BaliNo ratings yet

- A Critical Appraisal of The Concept of Plea Bargaining in Criminal Justice Delivery in NigeriaDocument13 pagesA Critical Appraisal of The Concept of Plea Bargaining in Criminal Justice Delivery in NigeriaMark-Arthur Richie E ObiNo ratings yet

- 024 1966 Mohammedan LawDocument20 pages024 1966 Mohammedan LawM.r. SodhaNo ratings yet

- Final ListDocument10 pagesFinal ListAshish RajNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction of The It Act 2000Document21 pagesJurisdiction of The It Act 2000Anurag Chaurasia100% (1)

- Distinction / Difference Between Public Nuisance and Private NuisanceDocument12 pagesDistinction / Difference Between Public Nuisance and Private Nuisanceankit vermaNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 49 Security For Keeping The Peace and For Good BehaviourDocument8 pagesCHAPTER 49 Security For Keeping The Peace and For Good BehaviourAmit GuptaNo ratings yet

- Conditions Restricting TransferDocument16 pagesConditions Restricting TransferSwati AnandNo ratings yet

- InsuranceDocument9 pagesInsurancePrashant MeenaNo ratings yet

- Adekeye and Others VDocument1 pageAdekeye and Others VAbū Bakr Aṣ-ṢiddīqNo ratings yet

- Lecture 4 - Strict LiabilityDocument8 pagesLecture 4 - Strict LiabilityJijoolNo ratings yet

- Joint Liability and Strict LiabilityDocument9 pagesJoint Liability and Strict LiabilityAnkit PathakNo ratings yet

- Tenure and EstatesDocument2 pagesTenure and EstatesAdam 'Fez' Ferris100% (2)

- Jurisdiction of The ICJ, HAGUEDocument17 pagesJurisdiction of The ICJ, HAGUECharity Lasi Magtibay100% (1)

- Burden of Proof and Standard of Proof in Civil LitigationDocument39 pagesBurden of Proof and Standard of Proof in Civil Litigationdecaa_513466129No ratings yet

- Legitimate Expectaion ConstiDocument10 pagesLegitimate Expectaion ConstiFongVoonYukeNo ratings yet

- Mod 2 - StatutesDocument24 pagesMod 2 - StatutessoumyaNo ratings yet

- Carriage by Land Legislation Relating To CarriageDocument3 pagesCarriage by Land Legislation Relating To CarriageAbha Kumari0% (1)

- Abha Project of SILDocument31 pagesAbha Project of SILAbha KumariNo ratings yet

- Women, S PropertyDocument60 pagesWomen, S PropertyAbha KumariNo ratings yet

- Disarmament: Aims & ObjectivesDocument6 pagesDisarmament: Aims & ObjectivesAbha KumariNo ratings yet

- InterpretationDocument31 pagesInterpretationricha sethiaNo ratings yet

- Arrogante V Deliarte DigestDocument2 pagesArrogante V Deliarte Digestztirb08100% (3)

- Salconmas SDN BHD V Ketua Setiausaha Kementerian Dalam Negeri & AnorDocument24 pagesSalconmas SDN BHD V Ketua Setiausaha Kementerian Dalam Negeri & AnorZueidriena HasanienNo ratings yet

- Trustees Fiduciary and Breach of FiduciaryDocument3 pagesTrustees Fiduciary and Breach of FiduciaryjohngaultNo ratings yet

- Answer GuanticDocument9 pagesAnswer GuanticAljunBaetiongDiazNo ratings yet

- Thomas v. Brockbank, 10th Cir. (2006)Document11 pagesThomas v. Brockbank, 10th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Case 1 ACAP vs. CADocument2 pagesCase 1 ACAP vs. CAGrey Kristoff AranasNo ratings yet

- The Negotiable Instruments Law of The PhilippinesDocument6 pagesThe Negotiable Instruments Law of The PhilippinesJames Cedrick NuasNo ratings yet

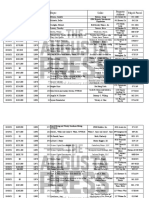

- Sale Date Sale Price Deed Book Deed Page Buyer Seller Property Address Map & ParcelDocument4 pagesSale Date Sale Price Deed Book Deed Page Buyer Seller Property Address Map & ParcelaugustapressNo ratings yet

- 562 Supreme Court Reports Annotated: Tibo vs. The Provincial CommanderDocument10 pages562 Supreme Court Reports Annotated: Tibo vs. The Provincial CommanderEllis LagascaNo ratings yet

- Succession Outline ReviewerDocument22 pagesSuccession Outline ReviewerChaNo ratings yet

- Adr Digest Pool-2Document88 pagesAdr Digest Pool-2Benedict Jonathan BermudezNo ratings yet

- Facebook Affidavit of IdentityDocument1 pageFacebook Affidavit of Identityacademyvr66No ratings yet

- Heirs of Medrano Vs de VeraDocument2 pagesHeirs of Medrano Vs de VerastephclloNo ratings yet

- CIVPRO Digests (3rd Batch) - Atty. FamadorDocument8 pagesCIVPRO Digests (3rd Batch) - Atty. FamadorJon Joshua FalconeNo ratings yet

- People's Homesite v. Jeremias (Digest)Document2 pagesPeople's Homesite v. Jeremias (Digest)Amin JulkipliNo ratings yet

- Goh Keng How V Raja Zainal Abidin Bin Raja HDocument22 pagesGoh Keng How V Raja Zainal Abidin Bin Raja HChin Kuen YeiNo ratings yet

- The Law Relating To CarriageDocument89 pagesThe Law Relating To CarriageMd Enamul HasanNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 310 The Law Reform - Fatal Accidents and Miscellaneous Provisions - Act FINAL CHAPA PDFDocument15 pagesCHAPTER 310 The Law Reform - Fatal Accidents and Miscellaneous Provisions - Act FINAL CHAPA PDFEsther MaugoNo ratings yet

- Succession Case DigestsDocument30 pagesSuccession Case DigestsRegine Yamas100% (4)

- A Research Paper On PartitionDocument15 pagesA Research Paper On Partitionlyka timanNo ratings yet

- Sample Complaint Revised Rules - Rse ClassDocument14 pagesSample Complaint Revised Rules - Rse ClassBenedict Jonathan Bermudez100% (11)

- Special Proceedings Green NotesDocument9 pagesSpecial Proceedings Green NotesNewCovenantChurchNo ratings yet

- Deed of Donation of A Portion of LandDocument1 pageDeed of Donation of A Portion of LandMarj ApolinarNo ratings yet

- Law of TortsDocument38 pagesLaw of TortsSrikrishnan S TNo ratings yet

- Parkland Complaint Full With ExhibitsDocument46 pagesParkland Complaint Full With ExhibitsLancasterOnlineNo ratings yet

- in Re SabioDocument14 pagesin Re SabioLGRRC DoseNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Change Color - EmeperadorDocument2 pagesAffidavit of Change Color - Emeperadorjoonee09No ratings yet