Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Brazil's Poor Pay World Cup Penalty: by Maria Carrión

Brazil's Poor Pay World Cup Penalty: by Maria Carrión

Uploaded by

api-236378779Copyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- DLS Player ListDocument12 pagesDLS Player ListSuyog Sabale75% (28)

- Gunning For Greatness Ozil PDFDocument301 pagesGunning For Greatness Ozil PDFFaiz SyedNo ratings yet

- São Paulo CASE STUDYDocument19 pagesSão Paulo CASE STUDYOussama KhallilNo ratings yet

- Atestat Engleza Cezar AlexiaDocument14 pagesAtestat Engleza Cezar Alexiagrasunica97No ratings yet

- Here's How The World Cup Will Boost Brazil's Economy: Official FIFA PartnersDocument19 pagesHere's How The World Cup Will Boost Brazil's Economy: Official FIFA PartnersAna-Maria CartasNo ratings yet

- Specter of State-Terror On The World CupDocument3 pagesSpecter of State-Terror On The World CupSushovan DharNo ratings yet

- Anti-World Cup Protests Across Brazil - World News - The Guardian 1Document4 pagesAnti-World Cup Protests Across Brazil - World News - The Guardian 1api-318390484No ratings yet

- The Economic Impact of The World Cup On BrazilDocument7 pagesThe Economic Impact of The World Cup On Brazileadona15No ratings yet

- Brasilia: Does Life Begin at 50?Document7 pagesBrasilia: Does Life Begin at 50?Ferdi AparatNo ratings yet

- 7 Injured in Anti-World Cup Protest in Brazil's Largest City: La Prensa: America in EnglishDocument4 pages7 Injured in Anti-World Cup Protest in Brazil's Largest City: La Prensa: America in EnglishvanikulapoNo ratings yet

- Postcards from Rio: Favelas and the Contested Geographies of CitizenshipFrom EverandPostcards from Rio: Favelas and the Contested Geographies of CitizenshipNo ratings yet

- LonelyPlanet CelebrateBrazilDocument11 pagesLonelyPlanet CelebrateBrazilAna PortelaNo ratings yet

- Brazil CultureDocument2 pagesBrazil CultureHarry Jay100% (1)

- Salvador BahiaDocument1 pageSalvador BahiaSamora Tooling EngineerNo ratings yet

- Notícia Internacional Sobre o Incêndio em Santa MariaDocument5 pagesNotícia Internacional Sobre o Incêndio em Santa MariaVinícius LauretoNo ratings yet

- Perspective of World Cup: Can It Change Brazil?: Li Xiaodong Wisuttilak Kiattidech Flávia Fonseca Reading, 8 May 2014Document20 pagesPerspective of World Cup: Can It Change Brazil?: Li Xiaodong Wisuttilak Kiattidech Flávia Fonseca Reading, 8 May 2014Flávia FonsecaNo ratings yet

- Rio Carnival FinalDocument3 pagesRio Carnival FinalKetaanNo ratings yet

- BrazilDocument13 pagesBrazilFABIANA VALERIA SANTANDER PATIÑONo ratings yet

- Sorting Actvoty SacostandbenefitsDocument6 pagesSorting Actvoty SacostandbenefitsAryan ShahNo ratings yet

- Sao PauloDocument26 pagesSao PauloCristian MateiNo ratings yet

- São Paulo-BrazilDocument1 pageSão Paulo-BrazilSamora Tooling EngineerNo ratings yet

- Textbook The Rough Guide To Brazil 9Th Edition Rough Guides Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook The Rough Guide To Brazil 9Th Edition Rough Guides Ebook All Chapter PDFbrandon.little460100% (1)

- Welcome To The 2014 World Cup: Travel Tips From A BrazilianFrom EverandWelcome To The 2014 World Cup: Travel Tips From A BrazilianNo ratings yet

- Brazils World Cup Opening Day Brings Protests Home Team Victory - La TimesDocument4 pagesBrazils World Cup Opening Day Brings Protests Home Team Victory - La Timesapi-318388572No ratings yet

- The Inherent Blindness Surrounding The 2014 World Cup GamesDocument2 pagesThe Inherent Blindness Surrounding The 2014 World Cup GamesOmar Alansari-KregerNo ratings yet

- Rio de JaneiroDocument6 pagesRio de JaneiroEmmanuel EspitiaNo ratings yet

- 06 VincenteDelRio UpgradingCitySquatterSettlementsDocument21 pages06 VincenteDelRio UpgradingCitySquatterSettlementsjéssica franco böhmerNo ratings yet

- Program, Which Has Provided Economic Opportunity For Over Ten Thousand Women inDocument3 pagesProgram, Which Has Provided Economic Opportunity For Over Ten Thousand Women inapi-33334754No ratings yet

- Rio de Janeiro: Brazil Carnival Christ The RedeemerDocument3 pagesRio de Janeiro: Brazil Carnival Christ The RedeemerWasay BokhariNo ratings yet

- DestinationsDocument10 pagesDestinationseun pureNo ratings yet

- How Kosovo, 'Brazil of The Balkans', Consoled A Nation's DisappointmentDocument9 pagesHow Kosovo, 'Brazil of The Balkans', Consoled A Nation's DisappointmentkeshavNo ratings yet

- How Migration Shapes An Intercultural CityDocument7 pagesHow Migration Shapes An Intercultural CityAngie GomezNo ratings yet

- History of Rio de Janeiro and Interesting Facts About CarnivalDocument3 pagesHistory of Rio de Janeiro and Interesting Facts About CarnivalAmanda MottaNo ratings yet

- São Paulo: Language Watch EditDocument7 pagesSão Paulo: Language Watch Editrosendo javier lopez colindresNo ratings yet

- Brazil-Step2 1Document8 pagesBrazil-Step2 1api-307925472No ratings yet

- PASS PaperDocument2 pagesPASS Paperstevenyin123No ratings yet

- International Sport Events DebateDocument2 pagesInternational Sport Events DebateHương LyNo ratings yet

- 9e63b2 RIODocument8 pages9e63b2 RIOarynmariegNo ratings yet

- Guia Turístico BrasíliaDocument94 pagesGuia Turístico BrasíliafabricaosNo ratings yet

- The Lack of Black Faces in The Crowds Shows Brazil Is No True Rainbow NationDocument2 pagesThe Lack of Black Faces in The Crowds Shows Brazil Is No True Rainbow NationAntonio Mota FilhoNo ratings yet

- Site Location: Rio de JanerioDocument11 pagesSite Location: Rio de JanerioAbdul SakurNo ratings yet

- Corruption Ecological: Rio-Empty-SeatsDocument5 pagesCorruption Ecological: Rio-Empty-SeatsAnonymous 3HTgMDONo ratings yet

- About RioDocument10 pagesAbout RioFiyi AweNo ratings yet

- A Port in Global Capitalism Unveiling Entangled Accumulation in Rio de Janeiro by Sérgio Costa Guilherme Leite GonçalvesDocument125 pagesA Port in Global Capitalism Unveiling Entangled Accumulation in Rio de Janeiro by Sérgio Costa Guilherme Leite Gonçalvesleitegoncalves-1No ratings yet

- Global Trade ReportDocument10 pagesGlobal Trade ReportAshik RahmanNo ratings yet

- Dancing with the Devil in the City of God: Rio de Janeiro on the BrinkFrom EverandDancing with the Devil in the City of God: Rio de Janeiro on the BrinkRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Brazilian FutebolDocument2 pagesBrazilian FutebolTomFahyNo ratings yet

- Brazil 2014Document2 pagesBrazil 2014Lemfedel MounibNo ratings yet

- Describing My City CaliDocument3 pagesDescribing My City CaliCarlos Alberto Arce FajardoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics On BrazilDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Topics On Brazilafeaynwqz100% (1)

- OlympicassignmentDocument7 pagesOlympicassignmentapi-316351737No ratings yet

- Place I Want To VisitDocument6 pagesPlace I Want To VisitttzafiroskaNo ratings yet

- Commonwealth Games VinayakDocument31 pagesCommonwealth Games VinayakManohar DhavskarNo ratings yet

- Sport Tourism Giro Ditalia IsraelDocument5 pagesSport Tourism Giro Ditalia IsraelJonathan CohenNo ratings yet

- Brochure BrazilDocument2 pagesBrochure Brazilapi-273414249100% (1)

- London Opens Up To The World As Travel Show Draws Thousands - Gulf Times 30 Oct 2014Document1 pageLondon Opens Up To The World As Travel Show Draws Thousands - Gulf Times 30 Oct 2014Updesh KapurNo ratings yet

- Jazeel - Kicking Off in Brazil - TJ Final VersionDocument22 pagesJazeel - Kicking Off in Brazil - TJ Final VersionGabrielMarquesFernandesNo ratings yet

- Some People Think That Hosting An International Sports Event Is Good For The CountryDocument1 pageSome People Think That Hosting An International Sports Event Is Good For The CountryMinh Đức NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Gabriela Meneghetti FR PDFDocument78 pagesGabriela Meneghetti FR PDFvedahiNo ratings yet

- Line Up Full TimeDocument1 pageLine Up Full TimeSapwan AhmedNo ratings yet

- World Cup 2011Document1 pageWorld Cup 2011Eknath Abhijeet BandodkarNo ratings yet

- Johan CruyffDocument18 pagesJohan Cruyffvague10No ratings yet

- ProfessionalDocument2 pagesProfessionalSyed Anas SohailNo ratings yet

- Abtaha MaqsoodDocument2 pagesAbtaha MaqsoodWikibaseNo ratings yet

- WCup 1.8.6 enDocument44 pagesWCup 1.8.6 enGhoya KartanegaraNo ratings yet

- Web Math Minute Add 15Document12 pagesWeb Math Minute Add 15sr_maiNo ratings yet

- FIFA WEEKLY Magazine Issue #06 - EnglishDocument40 pagesFIFA WEEKLY Magazine Issue #06 - EnglishM1DJNo ratings yet

- Martin Blasius: Fußball, Nationale Repräsentationen Und Gesellschaft. Die Fußballnationalmannschaft Im Jugoslawien Der 1980er JahreDocument40 pagesMartin Blasius: Fußball, Nationale Repräsentationen Und Gesellschaft. Die Fußballnationalmannschaft Im Jugoslawien Der 1980er Jahreblasiusm9492No ratings yet

- CM 2022 PiuraDocument11 pagesCM 2022 PiuraAnthony Hernaly Neyra HuamanNo ratings yet

- ICC Cricket World Cup 2011Document1 pageICC Cricket World Cup 2011paamerNo ratings yet

- Yuvraj & Harbhajan Back, Muraliistheonlysurprise: Manoj: Have To Be PatientDocument1 pageYuvraj & Harbhajan Back, Muraliistheonlysurprise: Manoj: Have To Be PatientPalash SwarnakarNo ratings yet

- Rise of A Football LegendDocument11 pagesRise of A Football Legendsamsunluak47No ratings yet

- Ergo March 19Document16 pagesErgo March 19Karthik100% (1)

- France vs. Argentina LIVE Score Updates: World Cup !nal Highlights As Kylian ..Document1 pageFrance vs. Argentina LIVE Score Updates: World Cup !nal Highlights As Kylian ..Gabriel ManjarrezNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument20 pagesDownloadFreestileMihaiNo ratings yet

- Municipality of Florence Stadio Artemio Franchi: Grado 1 Stadium Design RequirementsDocument29 pagesMunicipality of Florence Stadio Artemio Franchi: Grado 1 Stadium Design Requirementsfederico bosettiNo ratings yet

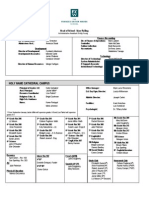

- Updated Faculty and Staff 2013-14 by LocationDocument2 pagesUpdated Faculty and Staff 2013-14 by LocationfxwwebmasterNo ratings yet

- Lionel Andrés MessiDocument3 pagesLionel Andrés MessiemmanueljosephNo ratings yet

- World Soccer 03 2024Document100 pagesWorld Soccer 03 2024Eddy ChanNo ratings yet

- Garrincha's TaleDocument4 pagesGarrincha's TaleDasha ChernenkoNo ratings yet

- PES2009 Player Database SortedDocument8 pagesPES2009 Player Database Sortednobbyeverton100% (1)

- Cricket World Cup 2011 ScheduleDocument1 pageCricket World Cup 2011 Scheduleapeksha_837No ratings yet

- Diego Maradona BiographyDocument2 pagesDiego Maradona BiographyJoaquin100% (2)

- Cronograma de Partidos Del Mundial Sub 20Document1 pageCronograma de Partidos Del Mundial Sub 20INFOnewsNo ratings yet

- Questions On SportsDocument9 pagesQuestions On SportsMadhavanNo ratings yet

- FIFA. (International Federation of Association Football)Document16 pagesFIFA. (International Federation of Association Football)maxdsNo ratings yet

Brazil's Poor Pay World Cup Penalty: by Maria Carrión

Brazil's Poor Pay World Cup Penalty: by Maria Carrión

Uploaded by

api-236378779Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Brazil's Poor Pay World Cup Penalty: by Maria Carrión

Brazil's Poor Pay World Cup Penalty: by Maria Carrión

Uploaded by

api-236378779Copyright:

Available Formats

26

u

July 2013

By Maria Carrin

Maria Carrin, former senior producer for Democracy

Now!, is a freelance journalist and documentary film-

maker based in Madrid.

Brazils Poor Pay

World Cup Penalty

Campello seemed keenly aware of the tension that

clung to the evening air as he cracked a few jokes

before launching into a peppy speech on the multiple

benefits of hosting soccers greatest tournament. Res-

idents patiently listened as he described plans that

included creating thousands of construction and ser-

vice jobs, recruiting volunteers, erecting canopies

with giant TV screens for the matches, and providing

free English lessons under a program called Ol tur-

ista (Hello, tourist).

As Campello concluded his talk, several residents

jumped from their seats for a turn at the microphone.

What about the evictions? asked a young man.

Can you tell us about plans to build a road

through our neighborhood? asked a woman.

We need health care and education, not mega-

events, said an older man to applause.

Nearby, local journalist Paulo Almeida broadcast the

event live on Bairro da Pazs community radio station.

As a parade of residents made their claims,

Campello seemed overwhelmed. I have to get back

to you with that, he kept repeating.

We are not interested in waving Brazilian flags or

volunteering for the World Cup, said longtime Bair-

ro da Paz resident and community activist Rafael

Lima after Campello had left. We need jobs. We

need education. We need land titles. We need health

care. And we need to know where this road they are

planning to build is going, and who will be affected.

Bairro da Paz is just one of many poor communi-

ties in Brazil facing evictions due to construction pro-

jects related to the 2014 World Cup, which will be

held in twelve cities throughout the country, and the

2016 Summer Olympics, which will take place in Rio

de Janeiro. Thousands of people in Brazil have

already been expelled from their homes, many in the

middle of the night, as bulldozers waited nearby to

make room for roads, stadiums, and other infrastruc-

ture. Citizens have responded by creating a network

of organizations to monitor and report abuses.

O

N A WARM EVENING THIS PAST FEBRUARY, ABOUT 100

residents of the Bairro da Paz, a favela located on the periphery of

the northeastern Brazilian city of Salvador da Bahia, gathered in a

community center to hear a presentation by Ney Campello, Bahias secretary

of state for the World Cup. Perched on a hill not far from the citys airport,

Bairro da Paz is one of Salvadors most politically active slums, and the crowd

that evening included schoolteachers, health care workers, and youth

activists anxious to hear firsthand how the 2014 World Cup would affect

their community.

Carrion 7.2013_FeatureD 12.2005x 6/4/13 6:21 PM Page 26

The Progressive

u

27

Raquel Rolnik, U.N. Special Rap-

porteur on Adequate Housing,

warned in 2011 about large-scale

human rights abuses committed

across Brazil in the name of World

Cup and Olympics construction. I

am particularly worried, she said,

about what seems to be a pattern of

lack of transparency, consultation,

dialogue, fair negotiation, and partic-

ipation of the affected communities

in processes concerning evictions

undertaken or planned in connection

with the World Cup and Olympics.

W

ith legendary players like

Pel and a national soccer

team revered for its grace-

ful, inimitable style, Brazil is consid-

ered the world capital of soccer. In

2007, when the country was awarded

the hosting of the 2014 World Cup,

Brazilians celebrated enthusiastically.

Then-president Luiz Incio Lula da

Silva, of the Workers Party, which has

done much to eradicate extreme

poverty, pledged that the Cup would

help Brazil upgrade its faltering infra -

structure, create thousands of jobs,

and promote the country internation-

ally as a modern, dynamic and diverse

place worth visiting and investing in.

In 2009, Lulas impassioned speech

before the International Olympic

Committee also won Brazil the 2016

Summer Olympic Games.

Soccer fever still abounds in Brazil,

but I found little enthusiasm for the

World Cup during my visit to Sal-

vador in February. Instead, reality has

set in. As my taxi driver, a fervent soc-

cer fan, told me on my first day, I

wish Argentina was hosting the World

Cup instead, and thats coming from

Argentinas eternal rival, a Brazilian.

According to estimates by the Uni-

versity of So Paolo, the World Cup

and the Olympics will together cost

Brazil about $33 billion. This

includes the massive overhaul of

national transportation infrastructure

such as airports, highways, train and

metro lines, and urban public trans-

port, and the construction of stadi-

ums and other sporting facilities. The

government has promised that these

investments will benefit all Brazilians

not just through improved infrastruc-

ture but also through long-term indi-

rect benefits from tourism and for-

eign investment.

But many Brazilians are question-

ing the governments projections.

They point to South Africa and the

United Kingdom as countries that

ended up with massive debt and little

return on their investments.

The Brazilian governments

promises that construction projects

would attract private financing have

largely failed to materialize, so tax-

payers are picking up most of the tab.

Of twelve stadiums built or

revamped whose costs have almost

tripled their projected budgets, ten

are publicly financed and between

four and eight will probably become

white elephants similar to those

that now dot the landscape in places

like Athens and Johannesburg.

S

alvador, Brazils third largest city,

will host the World Cup for one

week. The city has made com-

mitments to FIFA, the soccer govern-

ing body, to upgrade its crumbling

infrastructure, by building two access

Salvadors state-of-the-art stadium cost almost double the projected amount.

M

A

R

I

A

C

A

R

R

I

N

Carrion 7.2013_FeatureD 12.2005x 6/4/13 6:21 PM Page 27

28

u

July 2013

roads to the airport, completing a sub-

way line whose construction has lan-

guished for twelve years while its orig-

inal $500 million budget vanished,

and building a $300 million state-of-

the-art stadium, the Fonte Nova.

One criticism echoed by many res-

idents is the citys decision to raze its

old stadium, which offered public

sporting facilities, including athletic

fields, basketball courts, and the states

only public Olympic-size swimming

pool, where Bahias professional swim-

mers have trained. There are no plans

to rebuild these installations.

The new stadium was built by a pri-

vate-public consortium that includes

the Brazilian construction giant Ode-

brecht, also involved in reconstruction

efforts in Iraq and New Orleans, dia-

mond mining in Angola, and oil pro-

duction in Venezuela. Odebrecht,

which is building many of the other

stadiums for the Cup, has advanced

the money along with another compa-

ny, OAS, owned in part by the uncle of

Salvador Mayor A. C. M. Neto. The

government pledged to reimburse the

full amount while allowing the compa-

nies to exploit the venue for the next

thirty-five yearsa sweet deal by all

accounts.

We came to this arrangement

because the state does not have the

cash right now to build the stadium,

explains Jos Sergio Gabrielli, secre-

tary of state for planning, whose office

is responsible for seeking resources

and planning for many of these pro-

jects. Gabrielli also acknowledged to

me that except for the stadium and a

pedestrian bridge linking it to the his-

toric center, none of the other

promised infrastructure designed to

improve transportation will be ready

for 2014. Instead, the city will declare

World Cup week a holiday and create

special transportation corridors.

W

ith 3.5 million residents,

Salvador was Brazils first

capital city and the point

of entry for millions of African slaves

brought by the Portuguese to toil in

the sugar fields. Tourists are attracted

by its unique Afro-Brazilian culture

and a carnival that rivals that of Rio

de Janeiro. But Salvador is also a

deeply divided city. The gap between

the very wealthy and the very poor

remains dismal, public health and

education face shortages of every

kind, and the city suffers from high

rates of violent crime.

Salvadors population is over-

whelmingly black, yet the city has

never elected a black mayor. Its politi-

cal and economic power structures are

controlled by whites and remain prac-

tically out of reach for black Brazil-

ians. The upcoming World Cup has

brought these inequalities to the sur-

face. On the one hand, Afro-Brazilian

culture is used by the city and by FIFA

to attract visitors, but on the other,

most black Brazilians are excluded

from participation. The choice of

Ivete Sangalo, a popular white singer,

to perform Brazils national anthem

during the inauguration of Salvadors

stadium has offended many Afro-

Brazilians. As renowned black activist

Silvio Humberto, co-founder of the

Steve Biko Cultural Institute, who was

recently elected to Salvadors city

council, told me: We are not invited

to this party.

Humbertos words echoed

throughout my stay in Salvador as I

interviewed ordinary Brazilians about

the World Cup. Perhaps the most

publicized example of this exclusion

is the ban imposed by FIFA against

Salvadors emblematic Bahianas da

Acaraj, black women in lace dresses

who sell African-influenced food on

the streets. The ban, designed to ben-

efit official sponsors such as Coca-

Cola and McDonalds, will apply not

just inside the stadium but also with-

in a two-kilometer perimeter.

The soccer organization has

shown a total lack of respect for our

local culture and for what we repre-

sent, says Rita dos Santos, president

of the Association of Bahiana Sellers of

Acaraj, who has circulated a petition

on Change.org. Ten Bahianas

worked in the old stadium and now

we are told they cannot return because

of the ban and because they did not

design any space for them. So now

people will eat hamburgers instead?

The FIFA-imposed ban will also

affect the livelihood of hundreds of

other vendors who work the streets of

the city center, within the exclusion

zone. The city is already trying to reg-

ulate street vending for the Cup by

corralling sellers in officially desig-

nated areas. They will put me in a

corner, hidden from view, so how can

I make a living? says Vera Luzia

Mesias dos Santos, who braids hair in

the central Plaa da S.

O

ne of the more controversial

projects is a pedestrian

bridge linking the stadium

to Pelourinho, Salvadors historic

neighborhood, a UNESCO World

Heritage site and Salvadors main

tourist attraction. With its rows of

bright pastel colonial houses inter-

spersed with Renaissance churches,

Pelourinhos cobblestoned streets are

lined with souvenir stores and restau-

rants, and many of its buildings

house Afro-Brazilian cultural and

social centers. Its streets abound with

street vendors, capoeira groups, and

musicians. Its prettiest square, Largo

do Pelourinho, was the site of the

first slave market in the Americas.

But Afro-Brazilians describe the

place as an empty shell, a shopping

center for tourists, and they hardly

visit the neighborhood. In the 1990s,

as the city began to restore the crum-

bling buildings, it expelled its black

residents to peripheral favelas with no

infrastructure or social services. Jecil-

da Melo is one of the survivors. In

2002, she founded the Association of

Residents and Friends of Pelourinho,

and she and other families fought to

remain in their homes. We were a

group of women who said: No, we

are not leaving, Melo says as she sits

in the associations small headquar-

ters. Taking their case to the local

authorities, they finally obtained the

permanent right to remain in the

homes, although the land still belongs

to the government. They do not

Carrion 7.2013_FeatureD 12.2005x 6/4/13 6:21 PM Page 28

want poor people living here; we are

an embarrassment to them, she tells

me. And during the World Cup, they

will want us out of sight.

The projected pedestrian bridge,

with a conveyor belt, air condition-

ing, and a $100 million price tag,

would ferry fans from the matches to

the center of Pelourinho, bypassing

poor areas below. Meanwhile, the

mortals underneath will receive the

empty cans and the banana peels,

says Melo, wondering how the cash-

strapped city will maintain such a

costly bridge.

Up the street, Maura Cristina da

Silva, a housing rights activist, pon-

ders the fate of her community as she

sips coffee in her home on the

ground floor of a restored colonial

building she and another six families

occupied several years ago. Mostly

we are black women with kids who

have been expelled or priced out of

the housing market, she says. We

are fighting for the right to remain.

Da Silva forecasts a major social

cleansing effort in the historic district

by the city before the World Cup.

They will try to get rid of the

street people, the meninos da rua, and

anyone else who does not fit into their

postcard image, she says. The mes-

sage is: Poor and black, out of sight.

Bairro da Paz, where many of

Pelourinhos evicted ended up, is par-

ticularly vulnerable to forced removals

because more than 95 percent of its

residents do not have titles to their

homes or the land they are built on,

which means that they would receive

little or nothing in compensation.

Much of that land is privately owned,

and a 2010 city plan showed a large

section targeted for eviction.

Even the building we are in right

now has no title and could be expro-

priated, explains Marinalva Souza

Santos, president of Bairro da Pazs

neighborhood association, as we sit in

the associations community center.

There is a revolving door between

politics and real estate, and the World

Cup is the perfect excuse to go ahead

with development plans that had little

chance a few years ago due to local

opposition, says housing rights

lawyer Manoel Nascimento.

T

hese plans are in plain sight as

I approach Bairro da Paz on a

hot summer morning. The

view from my bus window as we veer

off the main highway and dip into

Bairro da Paz shows a landscape of

inequality. In the forefront, tiny com-

pact brick and wood houses cling to

steep hills connected by almost verti-

cal staircases carved into the dirt.

Sewage flows down potholed streets,

and small children play in the dirt.

Just a few hundred yards away,

dozens of high-rise luxury condo-

miniums, some still under construc-

tion, encircle the favela: The impossi-

bly wealthy elites, barricaded behind

electrified fences and protected by

private armed guards, loom over the

poor underneath.

Unfortunately for the residents,

they are sitting on prime property,

explains Nascimento, who works with

CEAS, a liberation theology nonprof-

it. This area is highly valuable: It is

close to the airport and to the beaches.

The sales offices for these high-rises

airbrushed Bairro da Paz from their

promotional photos and replaced it

with a green area. That definitely gave

away their real intentions.

Nascimento describes his surprise

when he saw the buildings begin to go

up in 2010 because the only way in and

out of them is through nearby favelas.

Soon afterward, the local govern-

ment unveiled its World Cup devel-

opment plans and it all became clear:

They had designed a road to service

these closed-gated communities, he

says. This is the road that would

split Bairro da Paz in two and dis-

place hundreds of families.

A year before the World Cup kick-

off, communities like Bairro da Paz

throughout Brazil have issued the

first red card of the tournament. It

may not be the last.

u

The Progressive

u

29

Bairro da Paz activists outside their community center, threatened by luxury

condo construction.

M

A

R

I

A

C

A

R

R

I

N

Carrion 7.2013_FeatureD 12.2005x 6/4/13 6:21 PM Page 29

You might also like

- DLS Player ListDocument12 pagesDLS Player ListSuyog Sabale75% (28)

- Gunning For Greatness Ozil PDFDocument301 pagesGunning For Greatness Ozil PDFFaiz SyedNo ratings yet

- São Paulo CASE STUDYDocument19 pagesSão Paulo CASE STUDYOussama KhallilNo ratings yet

- Atestat Engleza Cezar AlexiaDocument14 pagesAtestat Engleza Cezar Alexiagrasunica97No ratings yet

- Here's How The World Cup Will Boost Brazil's Economy: Official FIFA PartnersDocument19 pagesHere's How The World Cup Will Boost Brazil's Economy: Official FIFA PartnersAna-Maria CartasNo ratings yet

- Specter of State-Terror On The World CupDocument3 pagesSpecter of State-Terror On The World CupSushovan DharNo ratings yet

- Anti-World Cup Protests Across Brazil - World News - The Guardian 1Document4 pagesAnti-World Cup Protests Across Brazil - World News - The Guardian 1api-318390484No ratings yet

- The Economic Impact of The World Cup On BrazilDocument7 pagesThe Economic Impact of The World Cup On Brazileadona15No ratings yet

- Brasilia: Does Life Begin at 50?Document7 pagesBrasilia: Does Life Begin at 50?Ferdi AparatNo ratings yet

- 7 Injured in Anti-World Cup Protest in Brazil's Largest City: La Prensa: America in EnglishDocument4 pages7 Injured in Anti-World Cup Protest in Brazil's Largest City: La Prensa: America in EnglishvanikulapoNo ratings yet

- Postcards from Rio: Favelas and the Contested Geographies of CitizenshipFrom EverandPostcards from Rio: Favelas and the Contested Geographies of CitizenshipNo ratings yet

- LonelyPlanet CelebrateBrazilDocument11 pagesLonelyPlanet CelebrateBrazilAna PortelaNo ratings yet

- Brazil CultureDocument2 pagesBrazil CultureHarry Jay100% (1)

- Salvador BahiaDocument1 pageSalvador BahiaSamora Tooling EngineerNo ratings yet

- Notícia Internacional Sobre o Incêndio em Santa MariaDocument5 pagesNotícia Internacional Sobre o Incêndio em Santa MariaVinícius LauretoNo ratings yet

- Perspective of World Cup: Can It Change Brazil?: Li Xiaodong Wisuttilak Kiattidech Flávia Fonseca Reading, 8 May 2014Document20 pagesPerspective of World Cup: Can It Change Brazil?: Li Xiaodong Wisuttilak Kiattidech Flávia Fonseca Reading, 8 May 2014Flávia FonsecaNo ratings yet

- Rio Carnival FinalDocument3 pagesRio Carnival FinalKetaanNo ratings yet

- BrazilDocument13 pagesBrazilFABIANA VALERIA SANTANDER PATIÑONo ratings yet

- Sorting Actvoty SacostandbenefitsDocument6 pagesSorting Actvoty SacostandbenefitsAryan ShahNo ratings yet

- Sao PauloDocument26 pagesSao PauloCristian MateiNo ratings yet

- São Paulo-BrazilDocument1 pageSão Paulo-BrazilSamora Tooling EngineerNo ratings yet

- Textbook The Rough Guide To Brazil 9Th Edition Rough Guides Ebook All Chapter PDFDocument53 pagesTextbook The Rough Guide To Brazil 9Th Edition Rough Guides Ebook All Chapter PDFbrandon.little460100% (1)

- Welcome To The 2014 World Cup: Travel Tips From A BrazilianFrom EverandWelcome To The 2014 World Cup: Travel Tips From A BrazilianNo ratings yet

- Brazils World Cup Opening Day Brings Protests Home Team Victory - La TimesDocument4 pagesBrazils World Cup Opening Day Brings Protests Home Team Victory - La Timesapi-318388572No ratings yet

- The Inherent Blindness Surrounding The 2014 World Cup GamesDocument2 pagesThe Inherent Blindness Surrounding The 2014 World Cup GamesOmar Alansari-KregerNo ratings yet

- Rio de JaneiroDocument6 pagesRio de JaneiroEmmanuel EspitiaNo ratings yet

- 06 VincenteDelRio UpgradingCitySquatterSettlementsDocument21 pages06 VincenteDelRio UpgradingCitySquatterSettlementsjéssica franco böhmerNo ratings yet

- Program, Which Has Provided Economic Opportunity For Over Ten Thousand Women inDocument3 pagesProgram, Which Has Provided Economic Opportunity For Over Ten Thousand Women inapi-33334754No ratings yet

- Rio de Janeiro: Brazil Carnival Christ The RedeemerDocument3 pagesRio de Janeiro: Brazil Carnival Christ The RedeemerWasay BokhariNo ratings yet

- DestinationsDocument10 pagesDestinationseun pureNo ratings yet

- How Kosovo, 'Brazil of The Balkans', Consoled A Nation's DisappointmentDocument9 pagesHow Kosovo, 'Brazil of The Balkans', Consoled A Nation's DisappointmentkeshavNo ratings yet

- How Migration Shapes An Intercultural CityDocument7 pagesHow Migration Shapes An Intercultural CityAngie GomezNo ratings yet

- History of Rio de Janeiro and Interesting Facts About CarnivalDocument3 pagesHistory of Rio de Janeiro and Interesting Facts About CarnivalAmanda MottaNo ratings yet

- São Paulo: Language Watch EditDocument7 pagesSão Paulo: Language Watch Editrosendo javier lopez colindresNo ratings yet

- Brazil-Step2 1Document8 pagesBrazil-Step2 1api-307925472No ratings yet

- PASS PaperDocument2 pagesPASS Paperstevenyin123No ratings yet

- International Sport Events DebateDocument2 pagesInternational Sport Events DebateHương LyNo ratings yet

- 9e63b2 RIODocument8 pages9e63b2 RIOarynmariegNo ratings yet

- Guia Turístico BrasíliaDocument94 pagesGuia Turístico BrasíliafabricaosNo ratings yet

- The Lack of Black Faces in The Crowds Shows Brazil Is No True Rainbow NationDocument2 pagesThe Lack of Black Faces in The Crowds Shows Brazil Is No True Rainbow NationAntonio Mota FilhoNo ratings yet

- Site Location: Rio de JanerioDocument11 pagesSite Location: Rio de JanerioAbdul SakurNo ratings yet

- Corruption Ecological: Rio-Empty-SeatsDocument5 pagesCorruption Ecological: Rio-Empty-SeatsAnonymous 3HTgMDONo ratings yet

- About RioDocument10 pagesAbout RioFiyi AweNo ratings yet

- A Port in Global Capitalism Unveiling Entangled Accumulation in Rio de Janeiro by Sérgio Costa Guilherme Leite GonçalvesDocument125 pagesA Port in Global Capitalism Unveiling Entangled Accumulation in Rio de Janeiro by Sérgio Costa Guilherme Leite Gonçalvesleitegoncalves-1No ratings yet

- Global Trade ReportDocument10 pagesGlobal Trade ReportAshik RahmanNo ratings yet

- Dancing with the Devil in the City of God: Rio de Janeiro on the BrinkFrom EverandDancing with the Devil in the City of God: Rio de Janeiro on the BrinkRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Brazilian FutebolDocument2 pagesBrazilian FutebolTomFahyNo ratings yet

- Brazil 2014Document2 pagesBrazil 2014Lemfedel MounibNo ratings yet

- Describing My City CaliDocument3 pagesDescribing My City CaliCarlos Alberto Arce FajardoNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Topics On BrazilDocument6 pagesResearch Paper Topics On Brazilafeaynwqz100% (1)

- OlympicassignmentDocument7 pagesOlympicassignmentapi-316351737No ratings yet

- Place I Want To VisitDocument6 pagesPlace I Want To VisitttzafiroskaNo ratings yet

- Commonwealth Games VinayakDocument31 pagesCommonwealth Games VinayakManohar DhavskarNo ratings yet

- Sport Tourism Giro Ditalia IsraelDocument5 pagesSport Tourism Giro Ditalia IsraelJonathan CohenNo ratings yet

- Brochure BrazilDocument2 pagesBrochure Brazilapi-273414249100% (1)

- London Opens Up To The World As Travel Show Draws Thousands - Gulf Times 30 Oct 2014Document1 pageLondon Opens Up To The World As Travel Show Draws Thousands - Gulf Times 30 Oct 2014Updesh KapurNo ratings yet

- Jazeel - Kicking Off in Brazil - TJ Final VersionDocument22 pagesJazeel - Kicking Off in Brazil - TJ Final VersionGabrielMarquesFernandesNo ratings yet

- Some People Think That Hosting An International Sports Event Is Good For The CountryDocument1 pageSome People Think That Hosting An International Sports Event Is Good For The CountryMinh Đức NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Gabriela Meneghetti FR PDFDocument78 pagesGabriela Meneghetti FR PDFvedahiNo ratings yet

- Line Up Full TimeDocument1 pageLine Up Full TimeSapwan AhmedNo ratings yet

- World Cup 2011Document1 pageWorld Cup 2011Eknath Abhijeet BandodkarNo ratings yet

- Johan CruyffDocument18 pagesJohan Cruyffvague10No ratings yet

- ProfessionalDocument2 pagesProfessionalSyed Anas SohailNo ratings yet

- Abtaha MaqsoodDocument2 pagesAbtaha MaqsoodWikibaseNo ratings yet

- WCup 1.8.6 enDocument44 pagesWCup 1.8.6 enGhoya KartanegaraNo ratings yet

- Web Math Minute Add 15Document12 pagesWeb Math Minute Add 15sr_maiNo ratings yet

- FIFA WEEKLY Magazine Issue #06 - EnglishDocument40 pagesFIFA WEEKLY Magazine Issue #06 - EnglishM1DJNo ratings yet

- Martin Blasius: Fußball, Nationale Repräsentationen Und Gesellschaft. Die Fußballnationalmannschaft Im Jugoslawien Der 1980er JahreDocument40 pagesMartin Blasius: Fußball, Nationale Repräsentationen Und Gesellschaft. Die Fußballnationalmannschaft Im Jugoslawien Der 1980er Jahreblasiusm9492No ratings yet

- CM 2022 PiuraDocument11 pagesCM 2022 PiuraAnthony Hernaly Neyra HuamanNo ratings yet

- ICC Cricket World Cup 2011Document1 pageICC Cricket World Cup 2011paamerNo ratings yet

- Yuvraj & Harbhajan Back, Muraliistheonlysurprise: Manoj: Have To Be PatientDocument1 pageYuvraj & Harbhajan Back, Muraliistheonlysurprise: Manoj: Have To Be PatientPalash SwarnakarNo ratings yet

- Rise of A Football LegendDocument11 pagesRise of A Football Legendsamsunluak47No ratings yet

- Ergo March 19Document16 pagesErgo March 19Karthik100% (1)

- France vs. Argentina LIVE Score Updates: World Cup !nal Highlights As Kylian ..Document1 pageFrance vs. Argentina LIVE Score Updates: World Cup !nal Highlights As Kylian ..Gabriel ManjarrezNo ratings yet

- DownloadDocument20 pagesDownloadFreestileMihaiNo ratings yet

- Municipality of Florence Stadio Artemio Franchi: Grado 1 Stadium Design RequirementsDocument29 pagesMunicipality of Florence Stadio Artemio Franchi: Grado 1 Stadium Design Requirementsfederico bosettiNo ratings yet

- Updated Faculty and Staff 2013-14 by LocationDocument2 pagesUpdated Faculty and Staff 2013-14 by LocationfxwwebmasterNo ratings yet

- Lionel Andrés MessiDocument3 pagesLionel Andrés MessiemmanueljosephNo ratings yet

- World Soccer 03 2024Document100 pagesWorld Soccer 03 2024Eddy ChanNo ratings yet

- Garrincha's TaleDocument4 pagesGarrincha's TaleDasha ChernenkoNo ratings yet

- PES2009 Player Database SortedDocument8 pagesPES2009 Player Database Sortednobbyeverton100% (1)

- Cricket World Cup 2011 ScheduleDocument1 pageCricket World Cup 2011 Scheduleapeksha_837No ratings yet

- Diego Maradona BiographyDocument2 pagesDiego Maradona BiographyJoaquin100% (2)

- Cronograma de Partidos Del Mundial Sub 20Document1 pageCronograma de Partidos Del Mundial Sub 20INFOnewsNo ratings yet

- Questions On SportsDocument9 pagesQuestions On SportsMadhavanNo ratings yet

- FIFA. (International Federation of Association Football)Document16 pagesFIFA. (International Federation of Association Football)maxdsNo ratings yet