Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Guardian Reading

The Guardian Reading

Uploaded by

candifilmstudiesOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Guardian Reading

The Guardian Reading

Uploaded by

candifilmstudiesCopyright:

Available Formats

The Guardian, Saturday 21 December 2002

On a wing and a prayer

Using amateur actors and a traumatised chicken, City of God exposes the violent truth of life in the slums of Brazil. Here, the Oscar-winning director Walter Salles explains why it had to be made It begins with a chicken who knows too much. We are in City of God, a favela (a Rio de Janeiro slum) in the early 1980s. A gang of young drug-dealers is preparing feijoada, the local stew. This chicken knows that she is dead meat and tries desperately to escape. The tragi-comic scene that ensues determines the tone of City of God, a Brazilian film by Fernando Meirelles, co-directed by Katia Lund. The fleeing animal is chased and fired at by the young hoodlums until fate leads her under the wheels of a police car. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. City of God (Cidade de Deus) Production year: 2002 Country: Rest of the world Cert (UK): 18 Runtime: 135 mins Directors: Fernando Meirelles Cast: Alexandre Rodrigues, Leandro Firmino da Hora, Matheus Nachtergaele, Phelipe Haagensen

A clash between the young princes of the favela and the police is imminent and promises to be bloody. It will, however, be frozen in time, as Meirelles takes us to the 1960s and 1970s in the same locale. Based on a true account by Paulo Lins, a writer born and raised in the place that lends its name to the film, City of God does not offer the comforting and touristy image of the Brazilian slums that Marcel Camus's 1959 film Orfeu Negro sold to the world. This is about a nation within a nation, about the millions of olvidados (the forgotten) that are statistically relevant, but scarcely represented on screen. Rarely has a film created such heated debate in Brazil. The country's current leader, Luiz Inacio da Silva, at the time the socialist presidential candidate, urged the then president, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, to see City of God in order to understand the extent of the urban tragedy in Brazil. Cardoso did. Arnaldo Jabor, one of Brazil's most important intellectuals, wrote that "this is not only a film. It is an important fact, a crucial statement, a hole in our national conscience." After I directed the Oscar-winning Central Station, our small production house had the opportunity to help a few films by upcoming Brazilian directors. The decision to be part of City of God was defined by the trust we had in Meirelles and his co-director, but also because few films could shed more light on the social apartheid of Brazil. There are more than 40,000 violent deaths a year in Brazil, more than three times the total number of deaths in Kosovo. Many of these deaths in our urban areas are the result of confrontation between drug gangs, or between dealers and the police. What City of God achieves is the possibility to understand how we got to this chaos. In the 1960s, families of immigrants expelled from their land in the north-east of the country found an illusory refuge in the slums of the capital, Rio de Janeiro. The marginalised youth living

on the fringe of society at that time had to bend to strict familial codes and rules. The drug was marijuana, which inspired a contemplative, "romantic" lifestyle. Gun use at the time was sporadic and the ends justified the means. In the 1970s and 1980s everything changed. The first large drug-dealers appeared and outlaws ceased to lead a nomadic life and settled their businesses in the heart of the favelas. These dealers began to control the communities in which they operated and created a parallel system of justice within their borders. Cocaine became the drug of choice and the .38 was traded for the AK47 and other machine guns. The death toll grew dramatically and the dealers became younger and younger. It was hell. City of God follows several real characters, whose lives started and ended within the favela's perimeter during these three decades. Bene, the cool marijuana dealer, Ze Pequeo, a merciless killer, and Rocket, the innocent eye, Lins's alter ego, a young black kid who manages to break the country's social and race barriers - at a price. Most of the film's actors are kids from amateur theatre groups in favelas, or non-actors found in a year-long casting effort in these communities. The directors rehearsed them for more than six months before the shoot and improvisation was encouraged. Like other directors in Brazil, I am used to working with non-actors, but I still do not know how Meirelles and Lund managed to achieve such a sense of realism. Do not expect pity or redemption. There are no such things in City of God. This is the depiction of a world where people have been forgotten for too long by the Brazilian ruling classes; a world where the state does not provide proper health or education services. In fact, the only items it provides freely are bullets. Now for the present: a time when the olvidados got tired of being forgotten, a time of diffuse, uncontrollable violence. " City of God is not only a portrait of our favelas, it is also our portrait, at 24 frames a second, our faces blurred with the faces of 10-year-old children holding machine guns. All the manifestations of our chaos become visible. This film will be seen by the whole country in terror, and I believe it will cause transformations in the political arena," says Jabor. There were also dissonant voices in Brazil, arguing that the film gives the impression that favelas are populated only by drug-dealers. They are not. In fact, an immense part of the Brazilian population has been the victim of this present state. This is when we realise that the chicken caught in the cross-fire at the beginning of City of God is not only a chicken. It is the reflection of so many Brazilians trapped in an unjust country. City of God is released on January 3.

You might also like

- El Narco: Inside Mexico's Criminal InsurgencyFrom EverandEl Narco: Inside Mexico's Criminal InsurgencyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (22)

- The Gangster As Tragic HeroDocument4 pagesThe Gangster As Tragic HeroJirobuchon100% (2)

- Anansi Goes Fishing PDFDocument10 pagesAnansi Goes Fishing PDFBarbara SwensonNo ratings yet

- An Offer We Can't Refuse: The Mafia in the Mind of AmericaFrom EverandAn Offer We Can't Refuse: The Mafia in the Mind of AmericaNo ratings yet

- Living FireDocument64 pagesLiving FireSam WyseNo ratings yet

- An Ethic of The EstheticDocument11 pagesAn Ethic of The EstheticZelloffNo ratings yet

- GORDON, R. A. - A Narrative of National Reform - Quanto Vale Ou É Por Quilo - 2005Document20 pagesGORDON, R. A. - A Narrative of National Reform - Quanto Vale Ou É Por Quilo - 2005Marcelo SpitznerNo ratings yet

- Midterm Paper Cidade de DeusDocument7 pagesMidterm Paper Cidade de Deusordnas113No ratings yet

- The Exportation of Narconovelas From Latin America To The World Has Contributed On The Building of Stereotypes About The Region's CultureDocument4 pagesThe Exportation of Narconovelas From Latin America To The World Has Contributed On The Building of Stereotypes About The Region's CultureVeronica BahamonNo ratings yet

- Caesar. The Film Stared A Hot Headed Cunning Street Tough Named Rico. Rico Quickly BecameDocument4 pagesCaesar. The Film Stared A Hot Headed Cunning Street Tough Named Rico. Rico Quickly BecameElizabeth AriasNo ratings yet

- Name Year and Section: 1. Give 3 Scenes in The Movie That Are Reflective of The Current State of The Society and ExplainDocument4 pagesName Year and Section: 1. Give 3 Scenes in The Movie That Are Reflective of The Current State of The Society and ExplaincjNo ratings yet

- Morro Daniel Perl in Final Ed 1Document5 pagesMorro Daniel Perl in Final Ed 1danielperlinNo ratings yet

- 10 Best Documentaries of 2017 - Top Documentary Movies of The YearDocument30 pages10 Best Documentaries of 2017 - Top Documentary Movies of The Yearcharanmann9165No ratings yet

- Diken City of GodDocument12 pagesDiken City of Godtelemahos2No ratings yet

- Fernandez L'Hoeste From Rodrigo To Rosario 2008Document15 pagesFernandez L'Hoeste From Rodrigo To Rosario 2008Pedro Gonzales Duran0% (1)

- Movie City of God by Fernando MeirellesDocument36 pagesMovie City of God by Fernando MeirellesScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- A History of Place and SpaceDocument9 pagesA History of Place and SpaceCorinna100% (1)

- City of GodDocument6 pagesCity of GodPaul GibsonNo ratings yet

- The Politics in TreseDocument3 pagesThe Politics in TreseRianne MotasNo ratings yet

- Curry - Violence ColombiaDocument12 pagesCurry - Violence Colombiakyeong_eunpNo ratings yet

- City of GodDocument15 pagesCity of Godlarkana459835No ratings yet

- Colombia Again at The Crossroads. Peace, What Peace?Document3 pagesColombia Again at The Crossroads. Peace, What Peace?anpapisiNo ratings yet

- Amores PerrosDocument10 pagesAmores PerroserinakiNo ratings yet

- Multiculturalism in FilmDocument4 pagesMulticulturalism in FilmBrentNo ratings yet

- Brazilian Movies You Should WatchDocument2 pagesBrazilian Movies You Should WatchCélia NascimentoNo ratings yet

- The Best New True Crime Stories: Small TownsFrom EverandThe Best New True Crime Stories: Small TownsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- City of God EssayDocument3 pagesCity of God EssayBrian OlsenNo ratings yet

- Blade Runner:: - How Is The City Depicted in The Movie?Document4 pagesBlade Runner:: - How Is The City Depicted in The Movie?Eduward DragomirNo ratings yet

- Pixote, A Lei Do Mais Fraco: Between Fact and FictionDocument11 pagesPixote, A Lei Do Mais Fraco: Between Fact and Fictionalerre1No ratings yet

- Fresa y ChocoDocument6 pagesFresa y ChocoEsmeralda RoldanNo ratings yet

- Identitytheory - City of God ReviewDocument4 pagesIdentitytheory - City of God ReviewcandifilmstudiesNo ratings yet

- The World's Worst Serial Killers: Monsters whose crimes shocked the worldFrom EverandThe World's Worst Serial Killers: Monsters whose crimes shocked the worldNo ratings yet

- Rivera Et Al - Myth, Relative Evil and Anti-Hero in Narcos y Fariña 2022Document28 pagesRivera Et Al - Myth, Relative Evil and Anti-Hero in Narcos y Fariña 2022Nemo Castelli SjNo ratings yet

- Some People Have A Ghost Town, We Have A Ghost CityDocument20 pagesSome People Have A Ghost Town, We Have A Ghost CitygitaigoNo ratings yet

- Reflective Personal Essay: Assignment 2Document4 pagesReflective Personal Essay: Assignment 2Siddharth KumarNo ratings yet

- Richard Wright's Native Son As A Neo-Slave NarrativeDocument10 pagesRichard Wright's Native Son As A Neo-Slave Narrativeprofemina MNo ratings yet

- Marta Peixoto - Rios Favelas in Recent Fiction and FilmDocument9 pagesMarta Peixoto - Rios Favelas in Recent Fiction and FilmArthur PereiraNo ratings yet

- Insane Clown Pantheon: Comparative Mythology and the Dark Carnival. Carnival of Carnage and AzazelFrom EverandInsane Clown Pantheon: Comparative Mythology and the Dark Carnival. Carnival of Carnage and AzazelRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- The Death of J.P. CuencaDocument6 pagesThe Death of J.P. CuencaJoão Paulo CuencaNo ratings yet

- 1 Baker - 210818 - 002951Document5 pages1 Baker - 210818 - 002951thilaksafaryNo ratings yet

- New Left ReviewDocument20 pagesNew Left Reviewarun_shivananda2754No ratings yet

- Metaphor and Blade Runner's Racial PoliticsDocument27 pagesMetaphor and Blade Runner's Racial Politicsindiges7No ratings yet

- HUS 254 Final Exam Review PackageDocument13 pagesHUS 254 Final Exam Review PackageNerdy Notes Inc.No ratings yet

- Vigilantes and the Media: 8 Horrific True Crime Stories of Vigilantes: Murder for Justice, #1From EverandVigilantes and the Media: 8 Horrific True Crime Stories of Vigilantes: Murder for Justice, #1Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- The Ripper's Children: Inside the World of Modern Serial KillersFrom EverandThe Ripper's Children: Inside the World of Modern Serial KillersNo ratings yet

- Monsters IncDocument20 pagesMonsters IncMarc MarquetNo ratings yet

- True Crime Chronicles, Volume One: Serial Killers, Outlaws, and Justice ... Real Crime Stories From The 1800sFrom EverandTrue Crime Chronicles, Volume One: Serial Killers, Outlaws, and Justice ... Real Crime Stories From The 1800sNo ratings yet

- Mr. Claro - Modern Nonfiction Reading Selection by Charles Simic The Spider's WebDocument5 pagesMr. Claro - Modern Nonfiction Reading Selection by Charles Simic The Spider's WebNoran GomaaNo ratings yet

- Leanah S. Torio Section 6 Respeto: A Reflection of Our SocietyDocument3 pagesLeanah S. Torio Section 6 Respeto: A Reflection of Our SocietyJoana Tandoc100% (1)

- What's The Key To A 'Successful' Adaptation - VietceteraDocument10 pagesWhat's The Key To A 'Successful' Adaptation - VietceteraMaiLy1099No ratings yet

- Nexus Business ModelDocument12 pagesNexus Business ModelKommy AzarpourNo ratings yet

- Lamb As "Absolutely Awful, Ludicrous Movie - The Serial Killer That Doesn't Exist, Behaviors ThatDocument6 pagesLamb As "Absolutely Awful, Ludicrous Movie - The Serial Killer That Doesn't Exist, Behaviors ThatstarryfacehaoNo ratings yet

- Glauber Rocha. Aesthetics of HungerDocument4 pagesGlauber Rocha. Aesthetics of HungerIzadora XavierNo ratings yet

- G322 - Section B Film Industry Lesson 2Document10 pagesG322 - Section B Film Industry Lesson 2candifilmstudiesNo ratings yet

- G322 - Section B Film Industry: Lesson 2 Exam Theme 1 - AudiencesDocument10 pagesG322 - Section B Film Industry: Lesson 2 Exam Theme 1 - AudiencescandifilmstudiesNo ratings yet

- Notes On Blindness: Cognition Is BeautifulDocument25 pagesNotes On Blindness: Cognition Is BeautifulcandifilmstudiesNo ratings yet

- FDA Yearbook2016Document124 pagesFDA Yearbook2016candifilmstudiesNo ratings yet

- Bfi Statistical Yearbook 2016Document280 pagesBfi Statistical Yearbook 2016candifilmstudiesNo ratings yet

- Title Sequence Mark SchemeDocument2 pagesTitle Sequence Mark SchemecandifilmstudiesNo ratings yet

- Blog Mark SchemeDocument1 pageBlog Mark SchemecandifilmstudiesNo ratings yet

- Blog Mark SchemeDocument2 pagesBlog Mark SchemecandifilmstudiesNo ratings yet

- Evaluation Mark SchemeDocument2 pagesEvaluation Mark SchemecandifilmstudiesNo ratings yet

- Handout 1 Evaluating Social Media Case Study TextDocument3 pagesHandout 1 Evaluating Social Media Case Study TextcandifilmstudiesNo ratings yet

- Sarah Psychoanalytical TheoryDocument8 pagesSarah Psychoanalytical TheorycandifilmstudiesNo ratings yet

- Homework - Doc Martin Gender and Regional IdentityDocument2 pagesHomework - Doc Martin Gender and Regional IdentitycandifilmstudiesNo ratings yet

- Sarah Psychoanalytical TheoryDocument8 pagesSarah Psychoanalytical TheorycandifilmstudiesNo ratings yet

- Michael Jinadu - Autuer TheoryDocument6 pagesMichael Jinadu - Autuer TheorycandifilmstudiesNo ratings yet

- Usufruct TemplateDocument3 pagesUsufruct Templatekcsb researchNo ratings yet

- 2015-16 Khamanon Kamli 300 Khamanon Fatehgarh SahibDocument4 pages2015-16 Khamanon Kamli 300 Khamanon Fatehgarh Sahibraj soniNo ratings yet

- TRACCIA CALL - Al Arafah Islami Bank LimitedDocument9 pagesTRACCIA CALL - Al Arafah Islami Bank LimitedMd. Helal UddinNo ratings yet

- If Any: With BothDocument1 pageIf Any: With BothAkshat YadavNo ratings yet

- 5.de Borja Vs de BorjaDocument1 page5.de Borja Vs de BorjaTriciaNo ratings yet

- 24-85E-Social ScienceDocument6 pages24-85E-Social ScienceRosie RoseNo ratings yet

- Withdrawal Petition Jaya Basak 23 (3) CPCDocument6 pagesWithdrawal Petition Jaya Basak 23 (3) CPCBiltu DeyNo ratings yet

- Fatal Domestic ViolenceDocument8 pagesFatal Domestic ViolenceDesmond KevogoNo ratings yet

- Steering GearDocument5 pagesSteering Gearandreea.sultan1100% (1)

- Jaxity Fonseca DisobedienceDocument3 pagesJaxity Fonseca Disobedienceapi-458063024No ratings yet

- "Freedom Lies in Being Bold: EssayDocument3 pages"Freedom Lies in Being Bold: EssayOlya BragaNo ratings yet

- Static GK: Stadiums Around The WorldDocument4 pagesStatic GK: Stadiums Around The WorldanishNo ratings yet

- MANUAL-09 - Tricity - Start Page 6Document124 pagesMANUAL-09 - Tricity - Start Page 6SakshiNo ratings yet

- Callnames - PlayersDocument69 pagesCallnames - PlayersshafiraNo ratings yet

- Persons and Family Relations: Tape Is Are Not Allowed.)Document7 pagesPersons and Family Relations: Tape Is Are Not Allowed.)Jica GulaNo ratings yet

- COMPROMIS-2018: Justice P.N. Bhagwati Memorial International Moot Court Competition On Human RightsDocument14 pagesCOMPROMIS-2018: Justice P.N. Bhagwati Memorial International Moot Court Competition On Human RightsmohitNo ratings yet

- Limang Presidente NG PilipinasDocument10 pagesLimang Presidente NG PilipinasJonalle BumagatNo ratings yet

- Phil Assn of Free Labor Union Vs CallejaDocument3 pagesPhil Assn of Free Labor Union Vs CallejaAitor LunaNo ratings yet

- Voodoo Book ListDocument4 pagesVoodoo Book ListmjsfwfesNo ratings yet

- Sunshine Book Co. v. Summerfield, 355 U.S. 372 (1958)Document1 pageSunshine Book Co. v. Summerfield, 355 U.S. 372 (1958)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

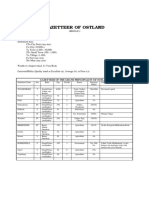

- Gazetteer of OstlandDocument5 pagesGazetteer of OstlandRatcatcher GeneralNo ratings yet

- 15 Revisting Constitutional Guarantees - Prof. Patricia R.P. Salvador DawayDocument46 pages15 Revisting Constitutional Guarantees - Prof. Patricia R.P. Salvador DawayJ. O. M. SalazarNo ratings yet

- Memorando Sentencia Usa A Radames BenitezDocument5 pagesMemorando Sentencia Usa A Radames BenitezVictor Torres MontalvoNo ratings yet

- Louis F. Budenz - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument5 pagesLouis F. Budenz - Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaAndemanNo ratings yet

- CRIMPRO Syllabus-2019Document14 pagesCRIMPRO Syllabus-2019millicentjhadeNo ratings yet

- Tryst With Destiny by Jawaharlal NehruDocument3 pagesTryst With Destiny by Jawaharlal Nehruparaschinu007100% (1)

- Convalidation Process IseDocument5 pagesConvalidation Process IsemancunNo ratings yet

- Flower Power LibreDocument1 pageFlower Power LibresurabhiraiifsNo ratings yet

- Quitclaim of An EmployeeDocument3 pagesQuitclaim of An EmployeeJasmin MiroyNo ratings yet