Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Violence

Violence

Uploaded by

munchy72Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Violence

Violence

Uploaded by

munchy72Copyright:

Available Formats

How does the infliction of pain through violence turn the body into a political sign?

The relationship between the nation state and the bodies of its people is one of complexity and ambiguity (Fassin 2011: 294). Within nation-states, the role of violence as a tool for political purposes has been widely discussed (Foucault 1977; Nagengast 1994). In a similar vein, this essay seeks to discuss the way in which the infliction of pain through violence turns the body into a political sign that can be used for political purposes, by both nation states as recognized social, physical and political entities and by those who seek to disrupt or reorder nation states. In order to accomplish this task, this essay considers violence to be a multifaceted concept with both visible and invisible consequences, something that can be socially constructed, but also physically and mentally felt, and as something which has the intention of causing some form of pain, either directly or indirectly (Scarry 1985; Nagengast 1994). By first exploring the notion of abjection and Scarrys (1985) ideas regarding the conscience and language destroying capabilities of violence and pain, the transformation of the body into a political sign can be discussed. This essay utilizes examples from torture and war specifically, in order to explain and discuss that transformation.

The concept of the abject is important is describing the unbridgeable mental and physical boundary present between the personal experience of violence and the

witnessing of violence. Whilst the abject, much like violence, has remained notoriously hard to define, broken down to its simplest form, the abject has only one quality of the object that of being opposed to it (Kristeva 1982: 1). In discussing the issue of rape in the context of war, Diken and Laustsen (2005: 113), go further to suggest the abject is not just something that threatens normality by being opposed to it, nor is it a pole in a binary distinction but indistinction itself. As an example, Diken and Laustsen (2005: 113) recognize the child of forced rape in the Bosnian civil war as an abject, something, which is never of the woman herself, and something that cannot be detached from her in a social sense. The abject in these examples is thus something that is recognized as not being of any object, whether external or internal, and thus it is always opposed. Considering this concept, this essay can turn now to the notion of pain and violence as abjection in order to examine political role of violence on the body.

Understanding pain as abjection allows for a recognition of the defying nature of expressing pain and the recognition of the gap between the personal experience of violence and the witnessing of violence. Scarry (1985) in her seminal piece on the body in pain recognizes the inexpressibility of pain. She suggests that the nature of pain is such that it defies verbal expression due to it being not of or for anything(Scarry 1985: 5). This implies that it is not in the realm of other verbally expressible objects, such as love or fear, but due to its nature is in the rather uncertain space of the unsharable. Whilst not using the term abject, pain is defined as an abjection, something that is not of any object yet which is felt and can often be seen. Scarry (1985: 5) goes further to suggest that the nature of pain

makes it, more than any other phenomenon [resistant to] objectification in language. Together these examples make for a compelling structure within which to first examine the gap between the witnessing and the experience of pain.

Due to pains inherent nature as something inexpressible, language is devoid of usefulness, and in a space where language is not used, the body becomes something on which meaning and understanding are evaluated. Appadurai (1998: 912) citing many others suggest that anthropology has long recognized the ways with which the body is used as a means of creating and representing cultural meaning. With specific regards to violence however, it is pain that stems from violence that becomes inscribed. Not only that but, what is at once a body in pain becomes, not only a symbol of pain itself, but a space for the representation and inscription of meaning, and thus a space of symbolic potential beyond the scope of the individual body. With the breakdown of the ability to verbally communicate what is being felt, the gap between the experience and the witnessing of violence becomes unbridgeable and the representation upon the injured body is open for political representation and misrepresentation.

The case of torture, in this regard, is particularly useful in explaining the way in which the body can be turned into a political sign. Scarry (1985: 20) asserts that torture, whilst not only physically painful is at its most intense, completely language deconstructing. Scarry (1985: 20) makes a careful distinction here between the use of destroy and deconstruct, preferring the latter in an effort to convey the sense that it is not a momentary destruction, but a complete

breakdown and exposure of the tortureds voice, as opposed to language, during torture that serves to both elicit pain and deny its presence. This simultaneous construction of pain and deconstruction of voice through torture, serves the purpose of providing a body on which to inscribe representations. As Foucault (1977: 44) suggests, torture serves the purpose of inscribing the truth upon the tortureds body, and in this instance the truth of which is constructed and created by the torturer. The denial, as Scarry (1985: 56) explains occurs in the translation of all the objectified elements of pain into the insignia of the regime. Here then is the central point of torture, that of the breakdown of verbal language and conscience such that a sign can be inscribed upon the body, thus making the body itself a symbol of the political environment.

On a broader scale, and often featuring torture, war is another site and cause of the transformation of the body into a political sign through pain and violence. The relationship between the body and the nation state is perhaps most important in this discussion of war, as it is often with the bodies of soldiers with which the war is fought and won or lost. The nature of bodily sacrifice in war is perhaps the most obvious display of the ability of pain and violence to turn the body into a political sign. As Scarry (1985: 112) notes, the body may be permanently or partially loaned in the act of war, thus forever being a symbol of the politics of war. Further to this, Green (1994) and Diken and Laustsen (2005), in their discussion of Guatemalan and Bosnian ethnic conflicts respectively, describe the way that the bodies of the dead and injured serve as physical representations of both the political regimes and the nature of the violence. The bodies have lost their ability to verbally express their pain, or in some

circumstances the bodies are so visibly injured that the political signs are too visible to look past. Diken and Laustsen (2005) also suggest that not only do the bodies of those injured become political signs, but they also serve to further inflict trauma on the family and community. The victims of war rape in this case are forever burdened with the physical and mental pain of the act committed, and with the social representation on their bodies as a victim of rape.

Thus, the transformation of the body into a political sign due to the infliction of pain through violence must be understood through a number of different concepts. At first the horror and abject nature of pain itself creates a situation whereby the pained is unable to verbalize the experience of their pain. This in turn creates an unbridgeable space between the experience in the body of the witness to such pain and the body experiencing the pain. This social void created by the difficulty in expressing pain thus serves to create a space whereby the body is open to visual representations. As has been noted by Scarry(1985: 14), The failure to express pain will always work to allow its appropriation and conflation with debased forms of power.

References Appadurai, Arjun (1998). 'Dead Certainty: Ethnic Violence in the Era of Globalization.' Development and Change, 29: 905-925. Diken, B., and Laustsen, C. (2005) Becoming Abject: Rape as a Weapon of War. Body & Society 11(1):111-128.

Fassin, D. (2011) The Trace: Violence, Truth, and the Politics of the Body. Social Research, 78(2). Foucault, Michael (1977) Discipline & Punishment , NY: Pantheon Books, pp. 3269. Green, L. (1994) Fear as a Way of Life. Cultural Anthropology, 9 (2): 227-256. Kristeva, J.(1982) Approaching Abjection Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, New York: Columbia University Press, , pp.1-31 Nagengast, C. (1994). 'Violence, Terror and the Crisis of the State.' Annual Review of Anthropology 23: 109-36. Scarry, E. (1985), The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World, Oxford University Press, New York.

You might also like

- Healing Collective Trauma: A Process for Integrating Our Intergenerational and Cultural WoundsFrom EverandHealing Collective Trauma: A Process for Integrating Our Intergenerational and Cultural WoundsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Understanding Judith ButlerDocument25 pagesUnderstanding Judith Butlermerakuchsaman100% (1)

- Trauma Signals in Life Stories by BenEzerDocument16 pagesTrauma Signals in Life Stories by BenEzermoebiustripNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Popular Culture and MediaDocument8 pagesRethinking Popular Culture and MediaThomasMaloryNo ratings yet

- The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of The World - Elaine ScarryDocument4 pagesThe Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of The World - Elaine Scarrygolinuji0% (1)

- Theories of Conflict PDFDocument12 pagesTheories of Conflict PDFCakama Mbimbi33% (3)

- (Artículo) Wurnser, León. Mortal Wound, Shame, and Tragic SearchDocument28 pages(Artículo) Wurnser, León. Mortal Wound, Shame, and Tragic SearchMaira Suárez ANo ratings yet

- Knowing the Suffering of Others: Legal Perspectives on Pain and Its MeaningsFrom EverandKnowing the Suffering of Others: Legal Perspectives on Pain and Its MeaningsNo ratings yet

- Good Night and Good Luck EssayDocument6 pagesGood Night and Good Luck EssayAnonymous 8g33yr100% (1)

- Naroda Patiya Judgment: Communalism CombatDocument80 pagesNaroda Patiya Judgment: Communalism CombatAfreen AzimNo ratings yet

- Rethinking The Body in Pain (By Michael McIntyre)Document30 pagesRethinking The Body in Pain (By Michael McIntyre)mmcintyrNo ratings yet

- The Body in Pain Notes PDFDocument3 pagesThe Body in Pain Notes PDFLorna BoNo ratings yet

- First-Order and Second-Order SufferingDocument16 pagesFirst-Order and Second-Order Sufferingmarcelo DuarteNo ratings yet

- In The Name of ResistanceDocument10 pagesIn The Name of ResistanceNicoleta AldeaNo ratings yet

- Vol13 No1 2017 Trauma and Counter Trauma Emanuel 655 2605 1 PB UatvwvDocument20 pagesVol13 No1 2017 Trauma and Counter Trauma Emanuel 655 2605 1 PB UatvwvDavid EinsteinNo ratings yet

- Peace Education 2Document3 pagesPeace Education 2Jen67% (3)

- I. Testimonio: The Witness, The Truth, and The InaudibleDocument2 pagesI. Testimonio: The Witness, The Truth, and The InaudibleMachete100% (1)

- Clara Han PDFDocument19 pagesClara Han PDFEnzo Antonio Isola SanchezNo ratings yet

- Clara Han PDFDocument19 pagesClara Han PDFCaro OjedaNo ratings yet

- Pols 415Document8 pagesPols 415nastya.amalovaNo ratings yet

- Violently Peaceful: Tibetan Self-Immolation and The Problem of The Non/Violence BinaryDocument15 pagesViolently Peaceful: Tibetan Self-Immolation and The Problem of The Non/Violence BinaryAtticus Peri JohnstonNo ratings yet

- Sara Ahmed, Lancaster University: Communities That Feel: Intensity, Difference and AttachmentDocument15 pagesSara Ahmed, Lancaster University: Communities That Feel: Intensity, Difference and AttachmentClaire BriegelNo ratings yet

- Types & Levels of ConflictDocument11 pagesTypes & Levels of ConflictNeelakshi TomarNo ratings yet

- Scheler Suffering SchubackDocument12 pagesScheler Suffering SchubackMignon14No ratings yet

- Disarming Weaponized Identities Limitations and Opportunities OICD EMICDocument26 pagesDisarming Weaponized Identities Limitations and Opportunities OICD EMICBruce WhiteNo ratings yet

- Johanna Oksala CH 2 Violence)Document26 pagesJohanna Oksala CH 2 Violence)sttbrownNo ratings yet

- 10 PDFDocument15 pages10 PDFPalin WonNo ratings yet

- The Humanitarian Politics of Testimony: Subjectification Through Trauma in The Israeli-Palestinian ConflictDocument28 pagesThe Humanitarian Politics of Testimony: Subjectification Through Trauma in The Israeli-Palestinian ConflictJohn StoufferNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Narratives of SufferingDocument19 pagesPhilosophical Narratives of SufferingEnric Benito OliverNo ratings yet

- My Final ProjectDocument53 pagesMy Final ProjectOgakason Rasheed Oshoke100% (1)

- Neitzsche KDocument7 pagesNeitzsche KnoNo ratings yet

- CH 1 (13-19) For PrintDocument7 pagesCH 1 (13-19) For PrintBekalu WachisoNo ratings yet

- Discourse and Social Theory LemkeDocument222 pagesDiscourse and Social Theory LemkeMarcelo SanhuezaNo ratings yet

- Recognition Gaps in The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The People-State and Self-Other AxesDocument33 pagesRecognition Gaps in The Israeli-Palestinian Conflict: The People-State and Self-Other AxesBenSandoval_86No ratings yet

- Can The Dead SpeakDocument7 pagesCan The Dead SpeakHéctor BezaresNo ratings yet

- The Language of TortureDocument18 pagesThe Language of TortureSam LudwigNo ratings yet

- Bio Politics and The Anthropology of Pain.Document3 pagesBio Politics and The Anthropology of Pain.Glenda JensenNo ratings yet

- Galtung Typology of Violence-1Document4 pagesGaltung Typology of Violence-1Cheryl Salude Romero100% (1)

- PagusiDocument18 pagesPagusiUmair AbdullahNo ratings yet

- Resentment and Ressentiment Bernard N. Meltzer, Central Michigan UniversityDocument16 pagesResentment and Ressentiment Bernard N. Meltzer, Central Michigan UniversityNikola At NikoNo ratings yet

- Galtung, Violence and Gender (Confortini) PDFDocument35 pagesGaltung, Violence and Gender (Confortini) PDFMustafa ZajaNo ratings yet

- On A Scale From 1 To 10: Life Writing and Lyrical PainDocument18 pagesOn A Scale From 1 To 10: Life Writing and Lyrical PainHS22D001 MalavikaNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Being Angry - Political Anger - European Journal of Social Theory 7 (2) 123-132Document10 pagesThe Importance of Being Angry - Political Anger - European Journal of Social Theory 7 (2) 123-132Adina IlieNo ratings yet

- Rethinking Edgar Tekere's A Lifetime of StruggleDocument14 pagesRethinking Edgar Tekere's A Lifetime of StruggleLinos TichazorwaNo ratings yet

- Revange Sources of Suffering BySalman AkhtarDocument20 pagesRevange Sources of Suffering BySalman Akhtarizastudias2No ratings yet

- Katerina Kolozova Identities Contribution Vol X PDFDocument8 pagesKaterina Kolozova Identities Contribution Vol X PDFsuudfiinNo ratings yet

- Reports From The FieldDocument26 pagesReports From The FieldEurípides BurgosNo ratings yet

- Coming To Our Senses:Appreciating The Sensorial in Medical AnthropologyDocument35 pagesComing To Our Senses:Appreciating The Sensorial in Medical AnthropologyTori SheldonNo ratings yet

- Cultural ViolenceDocument16 pagesCultural ViolenceGrupo Chaski / Stefan Kaspar100% (3)

- 1.2. The Conceptual Definitions of Peace and ConflictDocument31 pages1.2. The Conceptual Definitions of Peace and ConflictJdNo ratings yet

- Visitation - Love AC: When The Power of Love Over Comes The Love of Power, The World Will Truly Know PeaceDocument26 pagesVisitation - Love AC: When The Power of Love Over Comes The Love of Power, The World Will Truly Know PeaceAlexNo ratings yet

- Literature Review A. Existing StudiesDocument9 pagesLiterature Review A. Existing StudiesAlifya bkNo ratings yet

- Meaning of PeaceDocument4 pagesMeaning of PeaceMaYour BukhariNo ratings yet

- How Does Carole King's Song (You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman' Help To Illustrate The Cultural Politics of Emotion'?Document8 pagesHow Does Carole King's Song (You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman' Help To Illustrate The Cultural Politics of Emotion'?chiara blardoniNo ratings yet

- The Specifi City of Torture As Trauma:: The Human Wilderness When Words FailDocument23 pagesThe Specifi City of Torture As Trauma:: The Human Wilderness When Words FailMuhammad IlyasNo ratings yet

- The Stage and The Stake: 16 Century Anabaptist Martyrdom As Resistance To Violent SpectacleDocument17 pagesThe Stage and The Stake: 16 Century Anabaptist Martyrdom As Resistance To Violent SpectacleLeah WalkerNo ratings yet

- Understanding Violence Triangle and Structural ViolenceDocument2 pagesUnderstanding Violence Triangle and Structural ViolenceBobichand RajkumarNo ratings yet

- Political Thought 2Document4 pagesPolitical Thought 2Nikhilkumar BhosaleNo ratings yet

- 07 - Chapter-3.pdf Trauma and Third SpaceDocument14 pages07 - Chapter-3.pdf Trauma and Third Spaceyashica tomarNo ratings yet

- Journal of Conflict Resolution-2014-Lavi-68-92 PDFDocument25 pagesJournal of Conflict Resolution-2014-Lavi-68-92 PDFMohammad Zandi ZiaraniNo ratings yet

- The Contingency of PainDocument4 pagesThe Contingency of PainnikepaltomNo ratings yet

- Institutional Violence. Towards a New Approach: Legal Studies, #1From EverandInstitutional Violence. Towards a New Approach: Legal Studies, #1No ratings yet

- Amber Wright V Washington, Order State Defendant's Motion For Production OrderDocument7 pagesAmber Wright V Washington, Order State Defendant's Motion For Production OrderRick ThomaNo ratings yet

- MACN-A019 - Affidavit of Sovereign Personam Jurisdiction - Born NameDocument1 pageMACN-A019 - Affidavit of Sovereign Personam Jurisdiction - Born Namemoorish americanNo ratings yet

- PLJ Volume 84Document27 pagesPLJ Volume 84Mc NierraNo ratings yet

- Ibps Po MainsDocument18 pagesIbps Po MainsRaviraj GhadiNo ratings yet

- Industrial Relations GKDocument8 pagesIndustrial Relations GKGopi KrishnaNo ratings yet

- World War I and The Russian Revolution UnitDocument50 pagesWorld War I and The Russian Revolution Unitapi-455214046No ratings yet

- EulogyDocument3 pagesEulogyapi-310560627No ratings yet

- APUSH DBQ 1950sDocument4 pagesAPUSH DBQ 1950sDiana LeNo ratings yet

- Letter From Troy University Chancellor's Office To Board of TrusteesDocument2 pagesLetter From Troy University Chancellor's Office To Board of TrusteesahkotchNo ratings yet

- Behm SourceDocument14 pagesBehm SourceLily WebbNo ratings yet

- 'One Nation, One Election' - Feasible For India - PDFDocument4 pages'One Nation, One Election' - Feasible For India - PDFlalit vashistNo ratings yet

- 2014-8-4 Complaint and ExhibitsDocument243 pages2014-8-4 Complaint and ExhibitshasenrNo ratings yet

- Reforming The Health Sector in Developing Countries (Walt & Gilson)Document18 pagesReforming The Health Sector in Developing Countries (Walt & Gilson)Oghochukwu Franklin100% (1)

- ACC152 Example 8Document3 pagesACC152 Example 8Janna CereraNo ratings yet

- Islam Awr Kafalat-e-AamaDocument130 pagesIslam Awr Kafalat-e-AamaMinhajBooksNo ratings yet

- Politics of Women's Reservation in India: Satarupa PalDocument5 pagesPolitics of Women's Reservation in India: Satarupa PalAbhishek SaravananNo ratings yet

- APPSC Filling of Backlog Vacancies SC-STDocument2 pagesAPPSC Filling of Backlog Vacancies SC-STSEKHARNo ratings yet

- Amar Abhala Ewadha-अमर आभाळा एवढाDocument4 pagesAmar Abhala Ewadha-अमर आभाळा एवढाAnil Pundlik GokhaleNo ratings yet

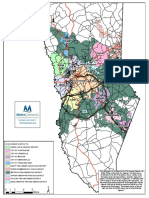

- Metro Connects Service Map As of 2016Document1 pageMetro Connects Service Map As of 2016AnnaBrutzmanNo ratings yet

- Himmler: The Father of The HolocaustDocument7 pagesHimmler: The Father of The HolocaustKyle SnyderNo ratings yet

- Commonwealth Games India Objective TestDocument4 pagesCommonwealth Games India Objective TestKirti BikramNo ratings yet

- UN Security CouncilDocument3 pagesUN Security Councilakashvir singhNo ratings yet

- Hey, Mayor Adams, Not Every Criticism Is About RaceDocument1 pageHey, Mayor Adams, Not Every Criticism Is About RaceRamonita GarciaNo ratings yet

- CLJ 2Document2 pagesCLJ 2Emmanuel De OcampoNo ratings yet

- Power Point For Social Studies 5th Grade LessonDocument7 pagesPower Point For Social Studies 5th Grade Lessonapi-240468923No ratings yet

- Jewish Standard, October 19, 2018Document67 pagesJewish Standard, October 19, 2018New Jersey Jewish StandardNo ratings yet

- Why Go To School - Wolk PDFDocument12 pagesWhy Go To School - Wolk PDFq234234234No ratings yet