Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Origin of Rural Women Empowerment

Origin of Rural Women Empowerment

Uploaded by

varunatkims12Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Origin of Rural Women Empowerment

Origin of Rural Women Empowerment

Uploaded by

varunatkims12Copyright:

Available Formats

Saturday, August 11, 2012 More Sharing ServicesShare | Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share on stumbleupon

Share on email Share on print | VIEW : Womens empowerment: a historical profile in India Dr Fatima Hussain The position of women in a society is the true index of its cultural and spiritual attainment. In the Rig Vedic age, women enjoyed a high position in Indian society Womens empowerment in India has had a long and rich history. Today, millions of ordinary women live, work and struggle to survive. Whether fighting for safe contraception, literacy, water or resisting sexual harassment, a vibrant and active womens movement thrives in many parts of India, aiming to empower them successfully. There are varied political and cultural circumstances under which groups of women organise themselves. Women organisations are not autonomous or free agents; rather they inherit a field and its accompanying social relations and when they act, they act in response to it and within it. The position of women in a society is the true index of its cultural and spiritual attainment. In the Rig Vedic age, women enjoyed a high position in Indian society. They had full freedom for spiritual and intellectual development. Gargi Vachaspati was one such distinguished woman of the era. Vedic literature has references, which recommend the assurance of the birth of a scholarly daughter. Daughters like sons were initiated into Vedic studies and had to lead a life devoted to learning self-control and discipline. Many women rose to become Vedic scholars, orators, poets and teachers. Some remained unmarried for a lifelong pursuit of knowledge and were called Brahmanavadinies. Women married at a mature age and were equal partners of their husbands in the performance of spiritual and temporal duties. They were free to attend public assemblies and were active participants in social activities. However, as society grew complex, the four-vama system based on occupation was replaced by the vama system based on birth. In the process, the status of women was reduced to that of shudras. Women ceased to be economically productive and their position became secondary. As taboos concerning smell and touch crystalised, women were forbidden to participate in religious sacrifices during periods of menstruation, confinement and child bearing, as they were considered unclean and untouchable. The Smriti writers like Manu, Yagnavalkya were issued mandates to EDITORIAL : Our treatment of Hindus COMMENT : Another one? Salman Tarik Kureshi VIEW : Why look up to others every time? Naeem Tahir VIEW : Womens empowerment: a historical profile in India Dr Fatima Hussain OVER A COFFEE : Waqar to Imran: the water car syndrome Dr Haider Shah COMMENT : Eat, pray, agitate Afrah Jamal LETTERS: KHALIDS CARTOON

discontinue the practice of Upanyas for daughters, which adversely affected their education. Characterising them as emotional and temperamental, Manu propounded the theory of the perpetual tutelage of women, along with other social taboos resulting in inhuman customs. The emergence of feudalism in around the fourth century relegated the status of women to that of property. With the advent of Islam in India, the status of women assumed a new form, as by that time, the males of the community had started interpreting Islamic injunctions selectively to suit patriarchal needs. Notwithstanding this, Queens Raziya Sultana and Nurjahan played a key role in shaping medieval Indian politics. With the advent of the British rule, a unique fusion of western and eastern thought took place. India came in contact with the modern west, where a far-reaching transformation had taken place in politics, economic and cultural spheres, giving impetus to a rethinking of values. Indian socio-religious reformers, who launched a campaign against social evils, especially relating to the treatment of women, took up a challenge to expunge child marriage, female infanticide, purdah system, sati, subjugation of widows, etc. In this direction, some Christian missionaries tried to persuade British government to abandon the policy of neutrality in social issues of Indians and legislate against the evil social customs. The idea of imparting education to Indian women by establishing exclusive schools for them originated from missionaries in 1819. English education opened a whole new world to Indian women, a world of social purposes, coloured by the ideals of liberalism, humanism, liberty and equality. The British government under William Bentick, abolished sati in 1829, later female infanticide was banned, and in 1856, the Widow Remarriage Act was passed. Ironically, it was men and not women, who initially took up the cause of womens empowerment in India. The forerunners in this field were Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar, Swami Dayananda Saraswathi; Keshab Chandra Sen, MG Ranade, Rabindranath Tagore, Swami Vivekanand, Virsalingam Pantulu, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, Gopal Krishna Gokhale and M K Gandhi. Thus, it was clear that national progress could not be achieved without the progress of women. Although men were first to take up the cause of women, the latter came up closely behind and organised themselves to work for their emancipation. The chief women to lead the nascent womens movement were Pandita Ramabai (1858-1922), Ramabai Ranade who presided over the Arya Mahila Samaj (1862-1924), Anandibai Joshi (1865-1887), Francina Sorabjee, Annie Jagannathan

and Rukmabai. Albeit they were unable to completely emancipate and empower Indian women, they did succeed in sowing the seeds of the womens movement in India. With the advent of the 20th century, the scope of womens movement began to enlarge rapidly, with a large number of women themselves making definite efforts in the fields of education and health. Demands for equal status of political rights found general expression through various women organisations. The trend towards feminism suddenly found powerful response in the country and the movements for liberation grew with remarkable vigour and audacity. Education made its way into the seclusion of the zenana and women emerged as socially and economically important. The speed with which India became welded into a single national unit had its impact on the womens movement. The unity of Indian womanhood began from about 1885 with the formation of the Indian National Congress. This was the first time that womens movements, which were until now expressing through individual efforts and aspirations, acquired an allembracing collective character. When Mahatma Gandhi entered the political scene, Indian women joined the National Movement in large members, thus giving great momentum to their own feminist movement. After the partition of Bengal, Gandhi gave a call to women to come forward for defying all social taboos, sacrificing physical comforts and denying the validity of all unreasonable restrictions, to take up political struggle. Gandhis unique contribution was the awakening of the immense untapped power in Indian womanhood, both urban and rural, for its utilisation for the progress of the Indian National Movement. The movement for political suffrage for women, even as early as 1917, was an evidence of the existence of self-consciousness among women. The arguments of Annie Besant, Sarojini Naidu, Herabai Tata and Mithan Tata were so convincing that British parliament decided to consider the question of womens suffrage a domestic subject, to be settled by Indian provincial legislation. By 1929, the vote was one of the links making Indian womanhood a vital unit in the life of the country. From around 1917, another subject came to infuse an all India unity among women, namely the health service. The organisation of All India Health Service along with Red Cross, AII India Maternity and Child Welfare Association and All India Central Conference took place. The Girls Guides movement also fostered unity among girls and loosened the bonds of conservatism. The linking process began by foundation of the All India Womens Conference in 1926 by Margaret

Cousins. This organisation fused all the scattered energies into a compact unit, a forum for redressing grievances raising demands and announcing their collective strength. The rural women did not lag far behind and supported the Salt Satyagraha protest march in 1929; in large numbers. They also joined the hand of desh-sevikas. Sarala Devi Devi Chaudhrani, Rustomji Faridoonji Durgabai Deshmukh, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, Vijay Laxmi Pandit, Kamala Devi Chattopadhya, Begum Sharifa Hamid Ali and Fatima Jinnah were other touch bearers of the embryonic womens movement in India. After the World War I, a new category of womens organisations began emerging. These carried a definite programme of social work and education, infused with a spirit of nationalism. As a result of the womens movement in India, women could secure equality of status with men. However, after 1947, womens movement in India slowed down and lost its somewhat frenzied pace. Nevertheless, the womens movement for empowerment continues its steady march forward. Today, Indian women are, in no way inferior to women in the rest of the world. A few among the galaxy of women who have brought laurels to India are Indira Gandhi, Mother Teresa, Kiran Bedi, Kalpana Chawala, Arundhati Roy and the list goes on. The writer is an associate professor of History at the Delhi University, India Home | Editorial More Sharing ServicesShare | Share on facebook Share on twitter Share on linkedin Share on stumbleupon Share on email Share on print | Daily Times - All Rights Reserved Site developed and hosted by WorldCALL Internet Solutions

Used books in Pakistan Web hosting in Pakistan

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Indian Railway Conventional Locomotive Basics To AllDocument484 pagesIndian Railway Conventional Locomotive Basics To AllHarsh Vardhan Singh85% (13)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The 1877 Genocide of 30 Million Hindus by The Christian British Ruler1Document2 pagesThe 1877 Genocide of 30 Million Hindus by The Christian British Ruler1ripestNo ratings yet

- Indian Painting BrowDocument166 pagesIndian Painting BrowCastshadNo ratings yet

- Junagadh StateDocument4 pagesJunagadh StateAziz0346No ratings yet

- Notice MergedDocument58 pagesNotice MergedPriya ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Thesis Report - Highrise Constrxn PDFDocument108 pagesThesis Report - Highrise Constrxn PDFNancy TessNo ratings yet

- EMB101 - Study Guide (Midterm)Document1 pageEMB101 - Study Guide (Midterm)akhlakhNo ratings yet

- Belonging To Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe: Form of Caste CertificateDocument2 pagesBelonging To Scheduled Caste or Scheduled Tribe: Form of Caste CertificateRajesh Kumar SahuNo ratings yet

- June-2016 W.L. Ty-IV VDocument6 pagesJune-2016 W.L. Ty-IV VRaju SutradharNo ratings yet

- Ultra Hni Data 2Document189 pagesUltra Hni Data 2PDRK BABIUNo ratings yet

- Challan No. 105915 Challan No. 105915 Challan No. 105915: Bank Stamp Bank Stamp Bank StampDocument1 pageChallan No. 105915 Challan No. 105915 Challan No. 105915: Bank Stamp Bank Stamp Bank StampSamad RazaNo ratings yet

- Gupta EmpireDocument10 pagesGupta EmpireSk SkNo ratings yet

- Education Reforms by British GovernmentDocument6 pagesEducation Reforms by British GovernmentSalmanNo ratings yet

- Indian National MovementDocument5 pagesIndian National MovementVijaya Kumar SNo ratings yet

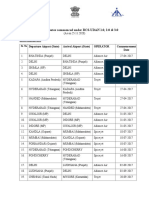

- List of RCS Routes Commenced Under RCS-UDAN 1.0, 2.0 & 3.0 RCS-UDAN 1.0Document11 pagesList of RCS Routes Commenced Under RCS-UDAN 1.0, 2.0 & 3.0 RCS-UDAN 1.0Arunesh DuttaNo ratings yet

- Marketing Practices by FMCG Companies For Rural Market: Institute of Business Management C.S.J.M University KanpurDocument80 pagesMarketing Practices by FMCG Companies For Rural Market: Institute of Business Management C.S.J.M University KanpurDeepak YadavNo ratings yet

- Project On Happily Unmarri Ed, Mumbai: Submitted By: Anish Adarkar Priyanka BaxiDocument16 pagesProject On Happily Unmarri Ed, Mumbai: Submitted By: Anish Adarkar Priyanka BaxipriyankabaxiNo ratings yet

- SoM January 2024Document10 pagesSoM January 2024gupta00987No ratings yet

- On Targeted Killings in Kashmir: July 2022Document2 pagesOn Targeted Killings in Kashmir: July 2022m ameenNo ratings yet

- A Study of Supply Chain Management of Vegetables in KaushambiDocument58 pagesA Study of Supply Chain Management of Vegetables in Kaushambianjali singhNo ratings yet

- Delhi SultanateDocument11 pagesDelhi SultanateKabeer PallikkalNo ratings yet

- The RSS Goal of Hindu Rashtra: - SaveraDocument22 pagesThe RSS Goal of Hindu Rashtra: - SaveraDebasis DashNo ratings yet

- Federal Bank BR ListDocument215 pagesFederal Bank BR Listthanseer003100% (1)

- Assignment - National Political PartiesDocument17 pagesAssignment - National Political PartiesMonishaNo ratings yet

- A TaleDocument5 pagesA TaleuverdavsuNo ratings yet

- Nationalism in India - Question BankDocument2 pagesNationalism in India - Question BankAADHINATH AJITHKUMARNo ratings yet

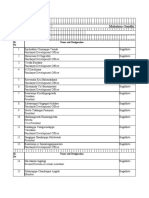

- Training On Renewable Energy, Rain Water Harvesting and Environment Protection (BagalkoteDocument572 pagesTraining On Renewable Energy, Rain Water Harvesting and Environment Protection (Bagalkotejaya duklanNo ratings yet

- Strategic Analysis of InfosysDocument40 pagesStrategic Analysis of InfosysMaruti VagmareNo ratings yet

- Gupta Trading Co. Gst-Challan Payment-1Document1 pageGupta Trading Co. Gst-Challan Payment-1Pradeep G NairNo ratings yet

- Religion and Religiousity CourseDocument5 pagesReligion and Religiousity CourseNeha BishlaNo ratings yet