Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Prescribing of Prism

The Prescribing of Prism

Uploaded by

JosepMolinsReixachCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

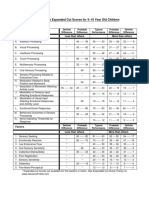

- Sensory Profile Expanded Cut Scores For 3-10 Year Old ChildrenDocument1 pageSensory Profile Expanded Cut Scores For 3-10 Year Old ChildrenAyra MagpiliNo ratings yet

- 8 The - Challenges - of - Amblyopia - TreatmentDocument6 pages8 The - Challenges - of - Amblyopia - TreatmentAndika SetiaNo ratings yet

- Presentation 1Document24 pagesPresentation 1-Yohanes Firmansyah-No ratings yet

- Accommodative and Binocular Vision Dysfunction in A Portuguese Clinical PopulationDocument7 pagesAccommodative and Binocular Vision Dysfunction in A Portuguese Clinical PopulationpoppyNo ratings yet

- Uveitis TopDocument9 pagesUveitis TopsrihandayaniakbarNo ratings yet

- MataDocument16 pagesMataIslah NadilaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Martijn VisserDocument146 pagesThesis Martijn Visserbismarkob47No ratings yet

- 12 Evidence Based Periodontology Systematic Reviews PDFDocument17 pages12 Evidence Based Periodontology Systematic Reviews PDFRohit ShahNo ratings yet

- Accommodative Changes With OrthokeratologyDocument10 pagesAccommodative Changes With OrthokeratologyGema FelipeNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2452232516302165 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S2452232516302165 MainIndah Nur LathifahNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Refractive Outcomes Between Femtosecond Laser-Assisted Cataract Surgery and Conventional Cataract SurgeryDocument7 pagesComparison of Refractive Outcomes Between Femtosecond Laser-Assisted Cataract Surgery and Conventional Cataract SurgeryoliviaNo ratings yet

- Contact Lenses Vs Spectacles in Myopes: Is There Any Difference in Accommodative and Binocular Function?Document12 pagesContact Lenses Vs Spectacles in Myopes: Is There Any Difference in Accommodative and Binocular Function?mau tauNo ratings yet

- Cureus 0014 00000029070Document7 pagesCureus 0014 00000029070abdi syahputraNo ratings yet

- Detecting Visual Field Progression: Ahmad A. Aref, MD, Donald L. Budenz, MD, MPHDocument6 pagesDetecting Visual Field Progression: Ahmad A. Aref, MD, Donald L. Budenz, MD, MPHJULIO COLAN MORANo ratings yet

- Isrn Orthopedics2013-940615Document8 pagesIsrn Orthopedics2013-940615Shahid HussainNo ratings yet

- Brolucizumab EstudioDocument13 pagesBrolucizumab EstudioJuan Carlos Mejía SernaNo ratings yet

- RPD Draft5 Group4Document4 pagesRPD Draft5 Group4api-527782385No ratings yet

- Jurnal PterygiumDocument5 pagesJurnal PterygiummirafitrNo ratings yet

- Computer Vision Syndrome 1Document10 pagesComputer Vision Syndrome 1Aaromal MaanasNo ratings yet

- Os Suportes Externos Melhoram o Equilíbrio Dinâmico em Pacientes Com Instabilidade Crônica Do Tornozelo - Uma Meta-AnáliseDocument19 pagesOs Suportes Externos Melhoram o Equilíbrio Dinâmico em Pacientes Com Instabilidade Crônica Do Tornozelo - Uma Meta-AnáliseThiago Penna ChavesNo ratings yet

- The Silent Gap Between Epilepsy Surgery Evaluations and Clinical Practice GuidelinesDocument2 pagesThe Silent Gap Between Epilepsy Surgery Evaluations and Clinical Practice GuidelinesAmelia PratiwiNo ratings yet

- 69 EdDocument10 pages69 EdAnna ListianaNo ratings yet

- Assisted Cataract Surgery Versus Standard UltrasoundDocument3 pagesAssisted Cataract Surgery Versus Standard UltrasoundNanda Tata NataNo ratings yet

- British Orthoptic Journal 2002Document9 pagesBritish Orthoptic Journal 2002roelkloosNo ratings yet

- Assessment of The Potential Iridology For Diagnosing Kidney Disease PDFDocument8 pagesAssessment of The Potential Iridology For Diagnosing Kidney Disease PDFSandya manoNo ratings yet

- Total or Partial Knee Arthroplasty Trial - TOPKAT: Study Protocol For A Randomised Controlled TrialDocument11 pagesTotal or Partial Knee Arthroplasty Trial - TOPKAT: Study Protocol For A Randomised Controlled TrialIvan DalitanNo ratings yet

- Treatment Based Subgroups LBP 2010Document11 pagesTreatment Based Subgroups LBP 2010Ju ChangNo ratings yet

- Science-Based Vision TherapyDocument2 pagesScience-Based Vision TherapyeveNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0161642022006698Document7 pagesPi Is 0161642022006698TRẦN NGỌC LAM THANHNo ratings yet

- Fundamentos Da BioestatisticaDocument7 pagesFundamentos Da BioestatisticaHenrique MartinsNo ratings yet

- VT Article On EfficacyDocument8 pagesVT Article On EfficacyEric ChowNo ratings yet

- JOVRDocument5 pagesJOVRkrishan bansalNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Radiology and Imaging Technology Ijrit 5 051Document7 pagesInternational Journal of Radiology and Imaging Technology Ijrit 5 051grace liwantoNo ratings yet

- American Journal of Emergency MedicineDocument5 pagesAmerican Journal of Emergency MedicineMaria teresa salinas merelloNo ratings yet

- Piis0161642014003893 PDFDocument10 pagesPiis0161642014003893 PDFZhakiAlAsrorNo ratings yet

- Decompression Alone Versus Decompression and Instrumented Fusion For The Treatment of Isthmic Spondylolisthesis-A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument11 pagesDecompression Alone Versus Decompression and Instrumented Fusion For The Treatment of Isthmic Spondylolisthesis-A Randomized Controlled TrialAnadya RhadikaNo ratings yet

- Termaat 2005Document11 pagesTermaat 2005OkyôAmêliâNo ratings yet

- Compliance With Soft Contact Lens Replacement Schedules and Associated Contact Lens-Related Ocular Complications: The UCLA Contact Lens StudyDocument10 pagesCompliance With Soft Contact Lens Replacement Schedules and Associated Contact Lens-Related Ocular Complications: The UCLA Contact Lens StudyMirza RisqaNo ratings yet

- ArticleDocument11 pagesArticleSandro PerilloNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia - 2017 - ChrimesDocument6 pagesAnaesthesia - 2017 - Chrimesannasoares02No ratings yet

- 17.PLDD Vs Surgery RCTDocument9 pages17.PLDD Vs Surgery RCTBeata SviantickaNo ratings yet

- Beck 1988Document3 pagesBeck 1988Sebastian RiveroNo ratings yet

- Long Term Impact of Immediate Versus Delayed TreatDocument9 pagesLong Term Impact of Immediate Versus Delayed TreatTinara HusniaNo ratings yet

- s2.0 S1877056819X000791 s2.0 S1877056819300866main - PDFX Amz Security Token IQoJbDocument8 pagess2.0 S1877056819X000791 s2.0 S1877056819300866main - PDFX Amz Security Token IQoJbSaheba SafiqueNo ratings yet

- Stadhouder 2008 SpineDocument12 pagesStadhouder 2008 SpineVijay JephNo ratings yet

- Emily Covington Critical Review RelaxofonDocument6 pagesEmily Covington Critical Review Relaxofonapi-254759511No ratings yet

- Surgery For Degenerative Lumbar Spondylosis: Updated Cochrane ReviewDocument9 pagesSurgery For Degenerative Lumbar Spondylosis: Updated Cochrane Reviewchartreuse avonleaNo ratings yet

- Moore 2024Document13 pagesMoore 2024youthcp93No ratings yet

- Interventions For Treating Pain and Disability in Adults With Complex Regional Pain Syndrome-An Overview of Systematic ReviewsDocument5 pagesInterventions For Treating Pain and Disability in Adults With Complex Regional Pain Syndrome-An Overview of Systematic ReviewsmahunNo ratings yet

- Critical Apraisal Fitria RizkiDocument5 pagesCritical Apraisal Fitria RizkiFitria RizkyNo ratings yet

- Screening of Patients Suitable For Diagnostic Cervical Facet Joint Blocks 2012Document4 pagesScreening of Patients Suitable For Diagnostic Cervical Facet Joint Blocks 2012Ricardo AugustoNo ratings yet

- Hans-Rudolf Weiss: IV. PhysiotherapyDocument21 pagesHans-Rudolf Weiss: IV. PhysiotherapyyaasarloneNo ratings yet

- Two Casting Methods Compared in Patients With Colles' Fracture: A Pragmatic, Randomized Controlled TrialDocument12 pagesTwo Casting Methods Compared in Patients With Colles' Fracture: A Pragmatic, Randomized Controlled TrialTeja Laksana NukanaNo ratings yet

- Operating Room EnviromentDocument8 pagesOperating Room EnviromentBruno AlcaldeNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Long-Term Surgical Outcomes of Two-Muscle Surgery in Basic-Type Intermittent Exotropia: Bilateral Versus UnilateralDocument9 pagesComparison of Long-Term Surgical Outcomes of Two-Muscle Surgery in Basic-Type Intermittent Exotropia: Bilateral Versus UnilateralerwinNo ratings yet

- Phacoemulsification Versus Small Incision Cataract Surgery in Patients With UveitisDocument6 pagesPhacoemulsification Versus Small Incision Cataract Surgery in Patients With UveitisYahya Iryianto ButarbutarNo ratings yet

- Screening For Eye Disease: Our Role, Responsibility and Opportunity of ResearchDocument2 pagesScreening For Eye Disease: Our Role, Responsibility and Opportunity of ResearchPierre A. RodulfoNo ratings yet

- Catarata UveíticaDocument8 pagesCatarata UveíticaJesus Rodriguez NoriegaNo ratings yet

- The Skeffington Perspective of the Behavioral Model of Optometric Data Analysis and Vision CareFrom EverandThe Skeffington Perspective of the Behavioral Model of Optometric Data Analysis and Vision CareNo ratings yet

- Renal Pharmacotherapy: Dosage Adjustment of Medications Eliminated by the KidneysFrom EverandRenal Pharmacotherapy: Dosage Adjustment of Medications Eliminated by the KidneysNo ratings yet

- Astigmatism - Optics Physiology and ManagementDocument318 pagesAstigmatism - Optics Physiology and ManagementJosepMolinsReixach100% (4)

- Scheiman Non-Surgical Interventions For CI Cochrane Review 2011Document60 pagesScheiman Non-Surgical Interventions For CI Cochrane Review 2011JosepMolinsReixachNo ratings yet

- Randomized Clinical Trial of Treatments For Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency in Children - Vision Therapy Was The Best TreatmentDocument14 pagesRandomized Clinical Trial of Treatments For Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency in Children - Vision Therapy Was The Best TreatmentJosepMolinsReixachNo ratings yet

- Randomised Clinical Trialof The Effectivenessof BIprism VSplaceboDocument7 pagesRandomised Clinical Trialof The Effectivenessof BIprism VSplaceboJosepMolinsReixachNo ratings yet

- An EvaluationDocument9 pagesAn EvaluationJosepMolinsReixachNo ratings yet

- Care of The Patient With Accommodative and Vergence DisfunctionDocument6 pagesCare of The Patient With Accommodative and Vergence DisfunctionJosepMolinsReixachNo ratings yet

- Accommodative Lag Using Dynamic Retinoscopy Age.10Document5 pagesAccommodative Lag Using Dynamic Retinoscopy Age.10JosepMolinsReixachNo ratings yet

- My Research ProposalDocument10 pagesMy Research ProposaloptometrynepalNo ratings yet

- Visual SystemDocument6 pagesVisual SystemJobelle Acena100% (1)

- Cranial Nerves (II)Document22 pagesCranial Nerves (II)ALONDRA GARCIANo ratings yet

- Kcal #ColorDocument12 pagesKcal #ColorRinaldhiHarifPunandityaNo ratings yet

- Cortical Deafness: Oleh: Dr. Laila Fajri Pembimbing: Dr. Novina Rahmawati, M.Si, Med, SP - THT-KL, FICSDocument18 pagesCortical Deafness: Oleh: Dr. Laila Fajri Pembimbing: Dr. Novina Rahmawati, M.Si, Med, SP - THT-KL, FICSzikral hadiNo ratings yet

- Assessing Neurologic System: Physical Assessment Guide To Collect Objective Client DataDocument3 pagesAssessing Neurologic System: Physical Assessment Guide To Collect Objective Client DataDanger JattNo ratings yet

- Monocular Elevation Deficiency (Double Elevator Palsy) A Cautionary NoteDocument2 pagesMonocular Elevation Deficiency (Double Elevator Palsy) A Cautionary NotePhilip McNelson100% (1)

- Eyes - Ears - Mouth - Nose (Lecture 5)Document50 pagesEyes - Ears - Mouth - Nose (Lecture 5)اسامة محمد السيد رمضانNo ratings yet

- Review: True or FalseDocument18 pagesReview: True or FalseAdorio JillianNo ratings yet

- Eye Movements in Reading and Information Processing: 20 Years of ResearchDocument51 pagesEye Movements in Reading and Information Processing: 20 Years of ResearchcraigspencerNo ratings yet

- Types of Hearing Loss: Md. Maruf Trainee Offr Otolaryngology & Head & Neck SurgeryDocument40 pagesTypes of Hearing Loss: Md. Maruf Trainee Offr Otolaryngology & Head & Neck SurgeryMaruf MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Advanced Audiology Nurses CourseDocument2 pagesAdvanced Audiology Nurses CourseKAUH EducationNo ratings yet

- Persuasive Speech Outline ENG 111 Date: 2020 Topic: AudienceDocument5 pagesPersuasive Speech Outline ENG 111 Date: 2020 Topic: AudienceMonira MstakimNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of HumphreyDocument42 pagesInterpretation of HumphreyRima Octaviani AdityaNo ratings yet

- Color Theory and DesignDocument15 pagesColor Theory and DesignJonathan JaphetNo ratings yet

- Lensa ProgresifDocument26 pagesLensa ProgresifMeironiWaimirNo ratings yet

- Ncm-116-Auditory-Disturbances 2Document24 pagesNcm-116-Auditory-Disturbances 2aaaawakandaNo ratings yet

- ColorTheory Princiles of Visual Design LCC 2720Document233 pagesColorTheory Princiles of Visual Design LCC 2720bryanNo ratings yet

- Duty Report 30 Maret 2018Document43 pagesDuty Report 30 Maret 2018riskhapangestikaNo ratings yet

- Color and Shade Matching in Operative DentistryDocument19 pagesColor and Shade Matching in Operative DentistryMarco Antonio García Luna100% (1)

- MalingeringDocument4 pagesMalingeringAnnamalai OdayappanNo ratings yet

- Ar Plate 92 - Pathway of Sound ReceptionDocument7 pagesAr Plate 92 - Pathway of Sound ReceptionmNo ratings yet

- Contact Lenses For Sporting ActivitiesDocument10 pagesContact Lenses For Sporting ActivitiesAlpaNo ratings yet

- University of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Science Department of Optometry Seminar On: AnisometropiaDocument42 pagesUniversity of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Science Department of Optometry Seminar On: Anisometropiahenok birukNo ratings yet

- Lensmeter by RenatoDocument25 pagesLensmeter by RenatoMuhammed AbdulmajeedNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan For K-12 Curriculum Science Grade 2Document7 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan For K-12 Curriculum Science Grade 2Angel Limbo100% (3)

- Physical Evidence and Servicescape 1Document16 pagesPhysical Evidence and Servicescape 1Abhi KumarNo ratings yet

- Complementary Colors: Complementary Colors Are Pairs of Colors Which, When Combined or MixedDocument8 pagesComplementary Colors: Complementary Colors Are Pairs of Colors Which, When Combined or MixedgamerootNo ratings yet

- Approach To A Patient With AstigmatismDocument57 pagesApproach To A Patient With AstigmatismNarendra N Naru100% (1)

The Prescribing of Prism

The Prescribing of Prism

Uploaded by

JosepMolinsReixachCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Prescribing of Prism

The Prescribing of Prism

Uploaded by

JosepMolinsReixachCopyright:

Available Formats

Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol (2008) 246:627629 DOI 10.

1007/s00417-008-0799-2

GUEST EDITORIAL

The prescribing of prisms in clinical practice

Lyle S. Gray

Received: 15 February 2008 / Accepted: 19 February 2008 / Published online: 1 April 2008 # Springer-Verlag 2008

Abstract The use of prisms in cases of decompensated heterophoria is an established treatment modality. The clinical literature lacks consensus upon the appropriate use of prisms, and fails to provide the necessary evidence base. While the experimental literature can guide the practitioner, the lack of double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical studies needs to be addressed. Keywords Prisms . Binocular . Vergence adaption The use of prisms in cases of binocular dysfunction is an important treatment modality for dealing with such patients [1]. The decision to prescribe a prism, and what value of prism to give, is subject to varying clinical opinions and practices [2]. The conservative view in clinical practice is that prisms should not be prescribed in the absence of symptoms of binocular dysfunction [1]. Furthermore, the prescribing of prisms is contraindicated in certain cases, due to the risk of exacerbating an existing condition through the process of vergence adaptation [36]. The control of the vergence response has been described previously using linear systems modelling [7], and can aid our understanding of the aetiology of binocular visual dysfunction, and the effect of clinical intervention. The normal vergence response operates in a closed-loop feedback system, where the total response is the sum of the outputs of two control elements with differing temporal

properties; a fast (phasic) control element and a slow (tonic) adaptive control element [7]. Previous reports have suggested that the strength of the adaptive vergence control element is often related to the presence of symptoms in patients with binocular dysfunction, and in severe cases the output of the adaptive vergence controller may be reduced to almost zero [8, 9]. In less severe cases, vergence adaptation may be present at a sub-normal level, but sufficient to produce an adaptive response to the introduction of a prism [8]. In such patients, strengthening the adaptive vergence control element is the treatment of first choice [8, 9]. Other studies have shown that in elderly patients vergence adaptation is very limited, and that while this may often be the cause of binocular dysfunction in these patients, remedial action with prisms is clinically viable because adaptation is very unlikely [10]. Indeed, we observe in our own binocular vision clinic that treatments designed to improve the strength of the adaptive vergence controller are generally unsuccessful in elderly patients. Typical clinical measures of binocular function, three of which are investigated by Otto et al. [11] in the current issue, are: 1. Heterophoria (or dissociated phoria). This represents the fusion-free position of the eyes, and therefore the magnitude of the deviation which has to be overcome by the vergence system. 2. Fixation disparity. First investigated by Ogle [12], this represents a small misalignment of the visual axes during binocular viewing, normally measured in seconds of arc. Many clinicians take the view that fixation disparity is indicative of stress within the binocular system [1]. Other authors regard fixation disparity to be a purposeful error, necessary for the vergence control system [5].

L. S. Gray (*) Department of Vision Sciences, Glasgow Caledonian University, Cowcaddens Road, Glasgow G4 0BA, UK e-mail: lsgr@gcal.ac.uk

628

Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol (2008) 246:627629

3. Associated heterophoria Mallett [13, 14] is the author associated with describing the clinical characteristics of this measurement, which measures the amount of prism required to reduce any fixation disparity (in 2 above) present to zero. In Malletts opinion, the presence of an associated phoria in a patient with symptoms of binocular vision dysfunction is indicative of stress within the binocular system, and requires treatment [15]. 4. Fusional vergence reserves. This is a clinical measure of the overall ability of the vergence system to control heterophoria. It is generally used in the calculation of Sheards Criterion [16], which requires the vergence reserves to be at least twice the size of any heterophoria present. There is evidence that the vergence reserves are related to the strength of the adaptive component of the vergence system [8, 9]. Each of these measures assess one specific aspect of binocular function, and while some practitioners prefer to rely on a particular measure to assess binocular function, others may assess a combination of the measures above to decide the most appropriate clinical intervention for the patient [2]. There is a lack of consensus in the literature about which of these measures correlates most closely with symptoms of binocular dysfunction, and which provides the most accurate basis for prescribing a prism when this is appropriate. Previous work has shown that no single measure correlates well with patient symptoms in all types of binocular anomaly, suggesting that neither fixation disparity, nor associated phoria, provide a universal indicator of binocular dysfunction [17]. This work also found that measures of vergence reserves often showed a better correlation with symptoms [17]. The imperative question for the clinician remains; is there a reliable method to determine the magnitude of prism required to compensate the heterophoria in patients suitable for this method of treatment? Mallett [15] suggested that the associated heterophoria identified the uncompensated portion of the binocular anomaly, and therefore this value represented the prism required to give the patient binocular comfort and stability. Other studies have questioned this [5, 17], and indeed the presence of an associated phoria in patients without binocular visual problems casts doubt on the general applicability of this measure [18]. Sheards criterion provides a rationale for prescribing prisms [1, 18]; however, there is still a lack of randomised controlled clinical trials to prove the efficacy of any treatment of binocular vision [2], although a recent study has begun to address this [19]. The use of a measure such as the comfortable prism, while clinically appealing, is highly subjective in nature, and would also require a clinical evidence base to prove efficacy. There is considerable work still to be done in the field of clinical management of

binocular vision dysfunction in order to provide the required evidence base. In all cases of binocular dysfunction, the choice to prescribe prisms lies with the clinician, who must judge what is most appropriate for each individual patient. A relatively straightforward procedure has been described to assess the probability of vergence adaptation occurring and rendering any prescribed prism ineffective [20]. Where prism treatment is being considered, obtain a prior measurement of the associated phoria, insert the prism to be prescribed into the trial frame and measure the associated phoria with the prism in situ. Allow the patient to wear the prism for 10 minutes; if the associated phoria returns to the value measured prior to insertion of the prism, then the patients vergence adaptation mechanism has been strong enough to overcome the prism, and it will have little clinical benefit. Conversely, if no vergence adaptation is observed, the patient is likely to derive significant clinical benefit from this treatment.

Acknowledgements The author would like to acknowledge the useful comments of Drs Niall Strang and Dirk Seidel in the preparation of this editorial.

References

1. Evans BJW (2002) Pickwells Binocular Vision Anomalies, 4th edn. Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford 2. O Leary CI, Evans BJW (2003) Criteria for prescribing optometric interventions: literature review and practitioner survey. Ophthal Physiol Opt 23:429439 3. North RV, Henson DB (1981) Adaptation to prism induced heterophoria in subjects with abnormal binocular vision or asthenopia. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 58:746752 4. North RV, Henson DB (1982) Effect of orthoptics upon the ability of patients to adapt to prism-induced heterophoria. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 59:983986 5. Schor CM (1983) Fixation disparity and vergence adaptation. In: Schor CM, Ciuffreda KJ (eds) Vergence eye movements: basic and clinical aspects. Butterworths, Boston 6. Lie I, Opheim A (1985) Long term acceptance of prisms by heterophorics. J Am Opt Assoc 56:272278 7. Schor CM, Kotulak JC (1986) Dynamic interactions between accommodation and convergence are velocity sensitive. Vision Res 26:927942 8. North RV, Henson DB (1992) The effect of orthoptic treatment upon the vergence adaptation mechanism. Optom Vis Sci 69:294299 9. Schor C, Horner D (1989) Adaptive disorders of accommodation and vergence in binocular dysfunction. Ophthal Physiol Opt 9:264268 10. Winn B, Gilmartin B, Sculfor DL et al (1994) Vergence adaptation and senescence. Optom Vis Sci 71:797800 11. Otto JMN, Kromeier M, Bach M, Kommerell G (2008) Do dissociated or associated phoria predict the comfortable prism? Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol [in press] 12. Ogle KN (1964) Researches in Binocular Vision. Hafner, New York 13. Mallet RFJ (1964) The investigation of heterophoria at near and a new fixation disparity technique. Optician 148:547551

Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol (2008) 246:627629 14. Mallet RFJ (1966) A fixation disparity test for distance use. Optician 152:18 15. Mallett RFJ (1974) Fixation disparityits genesis and relation to asthenopia. Ophthal Opt 14:11591168 16. Sheard C (1930) Zones of ocular comfort. Am J Optom 7:925 17. Sheedy JE, Saladin JJ (1983) Validity of diagnostic criteria and case analysis in binocular vision disorders. In: Schor CM, Ciuffreda KJ (eds) Vergence eye movements: basic and clinical aspects. Butterworths, Boston

629 18. Grisham JD (1983) Treatment of binocular dysfunctions. In: Schor CM, Ciuffreda KJ (eds) Vergence eye movements: basic and clinical aspects. Butterworths, Boston 19. O Leary CI, Evans BJW (2006) Double-masked randomised placebo-controlled trial of the effect of prismatic corrections on the rate of reading and the relationship with symptoms. Ophthal Physiol Opt 26:555565 20. Rosenfield M (1997) Tonic vergence and vergence adaptation. Optom Vis Sci 74:303328

You might also like

- Sensory Profile Expanded Cut Scores For 3-10 Year Old ChildrenDocument1 pageSensory Profile Expanded Cut Scores For 3-10 Year Old ChildrenAyra MagpiliNo ratings yet

- 8 The - Challenges - of - Amblyopia - TreatmentDocument6 pages8 The - Challenges - of - Amblyopia - TreatmentAndika SetiaNo ratings yet

- Presentation 1Document24 pagesPresentation 1-Yohanes Firmansyah-No ratings yet

- Accommodative and Binocular Vision Dysfunction in A Portuguese Clinical PopulationDocument7 pagesAccommodative and Binocular Vision Dysfunction in A Portuguese Clinical PopulationpoppyNo ratings yet

- Uveitis TopDocument9 pagesUveitis TopsrihandayaniakbarNo ratings yet

- MataDocument16 pagesMataIslah NadilaNo ratings yet

- Thesis Martijn VisserDocument146 pagesThesis Martijn Visserbismarkob47No ratings yet

- 12 Evidence Based Periodontology Systematic Reviews PDFDocument17 pages12 Evidence Based Periodontology Systematic Reviews PDFRohit ShahNo ratings yet

- Accommodative Changes With OrthokeratologyDocument10 pagesAccommodative Changes With OrthokeratologyGema FelipeNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2452232516302165 MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S2452232516302165 MainIndah Nur LathifahNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Refractive Outcomes Between Femtosecond Laser-Assisted Cataract Surgery and Conventional Cataract SurgeryDocument7 pagesComparison of Refractive Outcomes Between Femtosecond Laser-Assisted Cataract Surgery and Conventional Cataract SurgeryoliviaNo ratings yet

- Contact Lenses Vs Spectacles in Myopes: Is There Any Difference in Accommodative and Binocular Function?Document12 pagesContact Lenses Vs Spectacles in Myopes: Is There Any Difference in Accommodative and Binocular Function?mau tauNo ratings yet

- Cureus 0014 00000029070Document7 pagesCureus 0014 00000029070abdi syahputraNo ratings yet

- Detecting Visual Field Progression: Ahmad A. Aref, MD, Donald L. Budenz, MD, MPHDocument6 pagesDetecting Visual Field Progression: Ahmad A. Aref, MD, Donald L. Budenz, MD, MPHJULIO COLAN MORANo ratings yet

- Isrn Orthopedics2013-940615Document8 pagesIsrn Orthopedics2013-940615Shahid HussainNo ratings yet

- Brolucizumab EstudioDocument13 pagesBrolucizumab EstudioJuan Carlos Mejía SernaNo ratings yet

- RPD Draft5 Group4Document4 pagesRPD Draft5 Group4api-527782385No ratings yet

- Jurnal PterygiumDocument5 pagesJurnal PterygiummirafitrNo ratings yet

- Computer Vision Syndrome 1Document10 pagesComputer Vision Syndrome 1Aaromal MaanasNo ratings yet

- Os Suportes Externos Melhoram o Equilíbrio Dinâmico em Pacientes Com Instabilidade Crônica Do Tornozelo - Uma Meta-AnáliseDocument19 pagesOs Suportes Externos Melhoram o Equilíbrio Dinâmico em Pacientes Com Instabilidade Crônica Do Tornozelo - Uma Meta-AnáliseThiago Penna ChavesNo ratings yet

- The Silent Gap Between Epilepsy Surgery Evaluations and Clinical Practice GuidelinesDocument2 pagesThe Silent Gap Between Epilepsy Surgery Evaluations and Clinical Practice GuidelinesAmelia PratiwiNo ratings yet

- 69 EdDocument10 pages69 EdAnna ListianaNo ratings yet

- Assisted Cataract Surgery Versus Standard UltrasoundDocument3 pagesAssisted Cataract Surgery Versus Standard UltrasoundNanda Tata NataNo ratings yet

- British Orthoptic Journal 2002Document9 pagesBritish Orthoptic Journal 2002roelkloosNo ratings yet

- Assessment of The Potential Iridology For Diagnosing Kidney Disease PDFDocument8 pagesAssessment of The Potential Iridology For Diagnosing Kidney Disease PDFSandya manoNo ratings yet

- Total or Partial Knee Arthroplasty Trial - TOPKAT: Study Protocol For A Randomised Controlled TrialDocument11 pagesTotal or Partial Knee Arthroplasty Trial - TOPKAT: Study Protocol For A Randomised Controlled TrialIvan DalitanNo ratings yet

- Treatment Based Subgroups LBP 2010Document11 pagesTreatment Based Subgroups LBP 2010Ju ChangNo ratings yet

- Science-Based Vision TherapyDocument2 pagesScience-Based Vision TherapyeveNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0161642022006698Document7 pagesPi Is 0161642022006698TRẦN NGỌC LAM THANHNo ratings yet

- Fundamentos Da BioestatisticaDocument7 pagesFundamentos Da BioestatisticaHenrique MartinsNo ratings yet

- VT Article On EfficacyDocument8 pagesVT Article On EfficacyEric ChowNo ratings yet

- JOVRDocument5 pagesJOVRkrishan bansalNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Radiology and Imaging Technology Ijrit 5 051Document7 pagesInternational Journal of Radiology and Imaging Technology Ijrit 5 051grace liwantoNo ratings yet

- American Journal of Emergency MedicineDocument5 pagesAmerican Journal of Emergency MedicineMaria teresa salinas merelloNo ratings yet

- Piis0161642014003893 PDFDocument10 pagesPiis0161642014003893 PDFZhakiAlAsrorNo ratings yet

- Decompression Alone Versus Decompression and Instrumented Fusion For The Treatment of Isthmic Spondylolisthesis-A Randomized Controlled TrialDocument11 pagesDecompression Alone Versus Decompression and Instrumented Fusion For The Treatment of Isthmic Spondylolisthesis-A Randomized Controlled TrialAnadya RhadikaNo ratings yet

- Termaat 2005Document11 pagesTermaat 2005OkyôAmêliâNo ratings yet

- Compliance With Soft Contact Lens Replacement Schedules and Associated Contact Lens-Related Ocular Complications: The UCLA Contact Lens StudyDocument10 pagesCompliance With Soft Contact Lens Replacement Schedules and Associated Contact Lens-Related Ocular Complications: The UCLA Contact Lens StudyMirza RisqaNo ratings yet

- ArticleDocument11 pagesArticleSandro PerilloNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia - 2017 - ChrimesDocument6 pagesAnaesthesia - 2017 - Chrimesannasoares02No ratings yet

- 17.PLDD Vs Surgery RCTDocument9 pages17.PLDD Vs Surgery RCTBeata SviantickaNo ratings yet

- Beck 1988Document3 pagesBeck 1988Sebastian RiveroNo ratings yet

- Long Term Impact of Immediate Versus Delayed TreatDocument9 pagesLong Term Impact of Immediate Versus Delayed TreatTinara HusniaNo ratings yet

- s2.0 S1877056819X000791 s2.0 S1877056819300866main - PDFX Amz Security Token IQoJbDocument8 pagess2.0 S1877056819X000791 s2.0 S1877056819300866main - PDFX Amz Security Token IQoJbSaheba SafiqueNo ratings yet

- Stadhouder 2008 SpineDocument12 pagesStadhouder 2008 SpineVijay JephNo ratings yet

- Emily Covington Critical Review RelaxofonDocument6 pagesEmily Covington Critical Review Relaxofonapi-254759511No ratings yet

- Surgery For Degenerative Lumbar Spondylosis: Updated Cochrane ReviewDocument9 pagesSurgery For Degenerative Lumbar Spondylosis: Updated Cochrane Reviewchartreuse avonleaNo ratings yet

- Moore 2024Document13 pagesMoore 2024youthcp93No ratings yet

- Interventions For Treating Pain and Disability in Adults With Complex Regional Pain Syndrome-An Overview of Systematic ReviewsDocument5 pagesInterventions For Treating Pain and Disability in Adults With Complex Regional Pain Syndrome-An Overview of Systematic ReviewsmahunNo ratings yet

- Critical Apraisal Fitria RizkiDocument5 pagesCritical Apraisal Fitria RizkiFitria RizkyNo ratings yet

- Screening of Patients Suitable For Diagnostic Cervical Facet Joint Blocks 2012Document4 pagesScreening of Patients Suitable For Diagnostic Cervical Facet Joint Blocks 2012Ricardo AugustoNo ratings yet

- Hans-Rudolf Weiss: IV. PhysiotherapyDocument21 pagesHans-Rudolf Weiss: IV. PhysiotherapyyaasarloneNo ratings yet

- Two Casting Methods Compared in Patients With Colles' Fracture: A Pragmatic, Randomized Controlled TrialDocument12 pagesTwo Casting Methods Compared in Patients With Colles' Fracture: A Pragmatic, Randomized Controlled TrialTeja Laksana NukanaNo ratings yet

- Operating Room EnviromentDocument8 pagesOperating Room EnviromentBruno AlcaldeNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Long-Term Surgical Outcomes of Two-Muscle Surgery in Basic-Type Intermittent Exotropia: Bilateral Versus UnilateralDocument9 pagesComparison of Long-Term Surgical Outcomes of Two-Muscle Surgery in Basic-Type Intermittent Exotropia: Bilateral Versus UnilateralerwinNo ratings yet

- Phacoemulsification Versus Small Incision Cataract Surgery in Patients With UveitisDocument6 pagesPhacoemulsification Versus Small Incision Cataract Surgery in Patients With UveitisYahya Iryianto ButarbutarNo ratings yet

- Screening For Eye Disease: Our Role, Responsibility and Opportunity of ResearchDocument2 pagesScreening For Eye Disease: Our Role, Responsibility and Opportunity of ResearchPierre A. RodulfoNo ratings yet

- Catarata UveíticaDocument8 pagesCatarata UveíticaJesus Rodriguez NoriegaNo ratings yet

- The Skeffington Perspective of the Behavioral Model of Optometric Data Analysis and Vision CareFrom EverandThe Skeffington Perspective of the Behavioral Model of Optometric Data Analysis and Vision CareNo ratings yet

- Renal Pharmacotherapy: Dosage Adjustment of Medications Eliminated by the KidneysFrom EverandRenal Pharmacotherapy: Dosage Adjustment of Medications Eliminated by the KidneysNo ratings yet

- Astigmatism - Optics Physiology and ManagementDocument318 pagesAstigmatism - Optics Physiology and ManagementJosepMolinsReixach100% (4)

- Scheiman Non-Surgical Interventions For CI Cochrane Review 2011Document60 pagesScheiman Non-Surgical Interventions For CI Cochrane Review 2011JosepMolinsReixachNo ratings yet

- Randomized Clinical Trial of Treatments For Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency in Children - Vision Therapy Was The Best TreatmentDocument14 pagesRandomized Clinical Trial of Treatments For Symptomatic Convergence Insufficiency in Children - Vision Therapy Was The Best TreatmentJosepMolinsReixachNo ratings yet

- Randomised Clinical Trialof The Effectivenessof BIprism VSplaceboDocument7 pagesRandomised Clinical Trialof The Effectivenessof BIprism VSplaceboJosepMolinsReixachNo ratings yet

- An EvaluationDocument9 pagesAn EvaluationJosepMolinsReixachNo ratings yet

- Care of The Patient With Accommodative and Vergence DisfunctionDocument6 pagesCare of The Patient With Accommodative and Vergence DisfunctionJosepMolinsReixachNo ratings yet

- Accommodative Lag Using Dynamic Retinoscopy Age.10Document5 pagesAccommodative Lag Using Dynamic Retinoscopy Age.10JosepMolinsReixachNo ratings yet

- My Research ProposalDocument10 pagesMy Research ProposaloptometrynepalNo ratings yet

- Visual SystemDocument6 pagesVisual SystemJobelle Acena100% (1)

- Cranial Nerves (II)Document22 pagesCranial Nerves (II)ALONDRA GARCIANo ratings yet

- Kcal #ColorDocument12 pagesKcal #ColorRinaldhiHarifPunandityaNo ratings yet

- Cortical Deafness: Oleh: Dr. Laila Fajri Pembimbing: Dr. Novina Rahmawati, M.Si, Med, SP - THT-KL, FICSDocument18 pagesCortical Deafness: Oleh: Dr. Laila Fajri Pembimbing: Dr. Novina Rahmawati, M.Si, Med, SP - THT-KL, FICSzikral hadiNo ratings yet

- Assessing Neurologic System: Physical Assessment Guide To Collect Objective Client DataDocument3 pagesAssessing Neurologic System: Physical Assessment Guide To Collect Objective Client DataDanger JattNo ratings yet

- Monocular Elevation Deficiency (Double Elevator Palsy) A Cautionary NoteDocument2 pagesMonocular Elevation Deficiency (Double Elevator Palsy) A Cautionary NotePhilip McNelson100% (1)

- Eyes - Ears - Mouth - Nose (Lecture 5)Document50 pagesEyes - Ears - Mouth - Nose (Lecture 5)اسامة محمد السيد رمضانNo ratings yet

- Review: True or FalseDocument18 pagesReview: True or FalseAdorio JillianNo ratings yet

- Eye Movements in Reading and Information Processing: 20 Years of ResearchDocument51 pagesEye Movements in Reading and Information Processing: 20 Years of ResearchcraigspencerNo ratings yet

- Types of Hearing Loss: Md. Maruf Trainee Offr Otolaryngology & Head & Neck SurgeryDocument40 pagesTypes of Hearing Loss: Md. Maruf Trainee Offr Otolaryngology & Head & Neck SurgeryMaruf MahmoodNo ratings yet

- Advanced Audiology Nurses CourseDocument2 pagesAdvanced Audiology Nurses CourseKAUH EducationNo ratings yet

- Persuasive Speech Outline ENG 111 Date: 2020 Topic: AudienceDocument5 pagesPersuasive Speech Outline ENG 111 Date: 2020 Topic: AudienceMonira MstakimNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of HumphreyDocument42 pagesInterpretation of HumphreyRima Octaviani AdityaNo ratings yet

- Color Theory and DesignDocument15 pagesColor Theory and DesignJonathan JaphetNo ratings yet

- Lensa ProgresifDocument26 pagesLensa ProgresifMeironiWaimirNo ratings yet

- Ncm-116-Auditory-Disturbances 2Document24 pagesNcm-116-Auditory-Disturbances 2aaaawakandaNo ratings yet

- ColorTheory Princiles of Visual Design LCC 2720Document233 pagesColorTheory Princiles of Visual Design LCC 2720bryanNo ratings yet

- Duty Report 30 Maret 2018Document43 pagesDuty Report 30 Maret 2018riskhapangestikaNo ratings yet

- Color and Shade Matching in Operative DentistryDocument19 pagesColor and Shade Matching in Operative DentistryMarco Antonio García Luna100% (1)

- MalingeringDocument4 pagesMalingeringAnnamalai OdayappanNo ratings yet

- Ar Plate 92 - Pathway of Sound ReceptionDocument7 pagesAr Plate 92 - Pathway of Sound ReceptionmNo ratings yet

- Contact Lenses For Sporting ActivitiesDocument10 pagesContact Lenses For Sporting ActivitiesAlpaNo ratings yet

- University of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Science Department of Optometry Seminar On: AnisometropiaDocument42 pagesUniversity of Gondar College of Medicine and Health Science Department of Optometry Seminar On: Anisometropiahenok birukNo ratings yet

- Lensmeter by RenatoDocument25 pagesLensmeter by RenatoMuhammed AbdulmajeedNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan For K-12 Curriculum Science Grade 2Document7 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan For K-12 Curriculum Science Grade 2Angel Limbo100% (3)

- Physical Evidence and Servicescape 1Document16 pagesPhysical Evidence and Servicescape 1Abhi KumarNo ratings yet

- Complementary Colors: Complementary Colors Are Pairs of Colors Which, When Combined or MixedDocument8 pagesComplementary Colors: Complementary Colors Are Pairs of Colors Which, When Combined or MixedgamerootNo ratings yet

- Approach To A Patient With AstigmatismDocument57 pagesApproach To A Patient With AstigmatismNarendra N Naru100% (1)