Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Collaborative International Education: Reaching Across Borders

Collaborative International Education: Reaching Across Borders

Uploaded by

HANIZAWATI MAHATOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Collaborative International Education: Reaching Across Borders

Collaborative International Education: Reaching Across Borders

Uploaded by

HANIZAWATI MAHATCopyright:

Available Formats

The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available at www.emeraldinsight.com/1750-497X.

htm

INNOVATIVE PRACTICE

Collaborative international education: reaching across borders

Michael G. Hilgers, Barry B. Flachsbart and Cassandra C. Elrod

Department of Business & Information Technology, Missouri University of Science and Technology, Rolla, Missouri, USA

Abstract

Purpose As international boundaries fade and nancial pressures increase, universities are redening the norm in educational models. The move from a synchronous classroom to a blended classroom or a completely asynchronous environment has forced faculty to be creative in delivery while overcoming complexities in the associated infrastructure. Furthermore, geographic boundaries have diminished, leaving universities seeking ways to reach out to growing student markets, such as South-east Asia. However, this rapid international growth and nearly constant revision of delivery has raised serious questions regarding the maintenance of the quality and reputation of the institution. This is particularly challenging for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) programs requiring laboratory facilities, commercial software, and detailed, highly interactive theoretical analysis. The purpose of this paper is to describe the evolution, in the aforementioned environment, of a science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM)-centric university. Design/methodology/approach This paper will examine an example of using a local provider in an international setting to deliver content originating from three universities collaborating to deliver a single STEM degree. Findings The question of quality of education is found to overshadow this entire process, particularly given the strict constraints placed by accrediting organizations. Originality/value The example under consideration has addressed these issues in a variety of means, that is examined through the course of this paper as a case analysis. Keywords Sri Lanka, United States of America, Distance learning, Universities, Degrees, Higher education, Multicultural, Internet, Intercultural Paper type Case study

Collaborative international education 45

1. Introduction As international boundaries fade and nancial pressures increase, universities are redening the norm in educational models. Moving away from targeting on-campus students in the 18-22 year old range, schools are increasing reaching out to non-traditional students. Meeting the needs of students interested in a second career or graduate degrees while working full-time has forced many colleges to introduce extensive distance education programs. The move from a synchronous classroom to a blended classroom or a completely asynchronous environment has forced faculty to be creative in delivery while overcoming complexities in the associated infrastructure. Furthermore, geographic boundaries have diminished, leaving universities seeking ways to reach out to growing student markets, such as South-east Asia. However, this rapid international growth and nearly constant revision of delivery has raised serious questions regarding the maintenance of the quality and reputation of the institution,

Multicultural Education & Technology Journal Vol. 6 No. 1, 2012 pp. 45-56 q Emerald Group Publishing Limited 1750-497X DOI 10.1108/17504971211216319

METJ 6,1

46

particularly in situations involving multi-school collaborations. This is particularly challenging for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) programs requiring laboratory facilities, commercial software, and detailed, highly interactive theoretical analysis. This paper describes the evolution in the aforementioned environment of a STEM-centric university. While caring deeply about the quality of the education it delivers and its overall reputation, the specialized nature of its curriculum has driven it beyond the shrinking US pool of traditional students to nontraditional and international markets. In particular, this paper will examine an example of using a local provider in an international setting to deliver content originating from three universities collaborating to deliver a single STEM degree. This approach has not only proven to be successful but is redening the blended classroom in the domestic market. The question of quality of education underpins this entire process; particularly given the strict constraints placed by accrediting organizations. Infrastructure challenges exist at almost every level: overcoming basic differences between British and US approaches to education, using learning management systems (LMSs) to deliver content, managing software licenses using virtual servers, and the like. The example under consideration has addressed these issues in a variety of means that will be examined through the course of this paper. 2. Background This section will give background on technology, distance education and international collaboration. These components are key in the nature of this narrative. Global demands on the modern university are inducing a transformation (Morrison, 2003) from traditional synchronous classroom instruction to on-demand, asynchronous delivery (Howard et al., 2004) even prompting research into this evolutionary process as well as the associated methodologies (Cesarone, 2003). Without a doubt, institutional infrastructure, tradition, and history introduce an inertia to change (Kunstler, 2005) that must be understood and managed, yet cannot be allowed to dominate in the face of change (Eisenbarth, 2003). Kirkwood and Price (2006) argue that a distinction between information and communication technologies must be made at the highest level but that these concepts are often confused. This leads to a misunderstanding between e-learning and distance education (Eisenbarth, 2003). In fact, most of the technologies that make e-learning functional are used by non-distance students (Guri-Rosenblit, 2005). Institutions desire to make the learning process both efcient and effective. Developing content for distance education is expensive in time and resource; so many people have examined how to reuse learning materials (Hilgers et al., 2004; Shiratuddin and Landoni, 2003). Effectiveness research extends to emotional response on the part of the student at a psychological level (Larsen and Diener, 2001; Wilfred et al., 2004). It is argued that change should not be made for changes-sake (Njenga and Henry, 2010). In some of the earlier literature, a number of problems identied were viewed as nearly insurmountable, often leading to the conclusion that higher education was resistant to e-learning (Cheese, 2003) by the faculty and frustration on the part of the students (Hara, 1999). Later research addressed the delivery of online education, reaching the conclusion that the internet is more suited for some students than for others (Gosen, 2003; Wellington et al., 2005). Furthermore, a lack of effective marketing strategies of programs (Eisenbarth, 2003) and inadequacy of evaluations of the offerings

was also seen as a problem (Brancheau and Wetherbe, 1994; Compora, 2003). In fact, some strong criticisms dealing with inadequate preparation and implementation of mission statements, a lack of internal or external needs assessment, inconsistency on how programs are approved, widely varying delivery methods, and little help for students were all identied in surveying various distance education programs (Compora, 2003; Koontz et al., 2006). In spite of some perceived difculties, though, distance education is strongly in place in Universities today and the various components are subject to careful examination (Moore and Kearsley, 1996). Distance education has become a standard in higher education; administrators see themselves as facilitators of the distance programs, although not responsible for the implementation (Husmann and Miller, 2001). While much of the development of distance education has taken place in developed countries, demand for easier access, convenience, and lower cost is changing the higher education system and global competition is driving continuing change, including a global outlook (Lenn, 2000). Education in developing Asia brings different challenges to the forefront, especially in the area of nancing (Bray and Lee, 2001). Bray and Lee (2001) also makes the point that all Asian countries operate in a context of globalization, with education seen as a major investment for social and economic gains. The inuences shaping higher education were grouped into three fundamental changes for the next several decades, including globalization of higher education, impact of technology on changing the denitions of students and faculty, and the impact of the marketplace on the basic business model of higher education (Mellow and Woolis, 2010). A call for addressing the issue of global mandates to deal with terms such as knowledge capital was also identied as a need (Teichler, 2004). Although there has been an explosion of higher education and providers of it, there are still sensitive areas, such as the legalities of educating across borders and cultures (Lenn, 2000). Nonetheless, it is believed that universities will have absolutely no limitations geographically when implementing marketing strategies and that internet access will be the only criteria (Feng and Morrison, 2003). We can infer from the various approaches in the literature that distance learning will continue to play a role and that globalization and collaboration will be important. The next sections describe a case history that moves in this way and identies some of the continuing challenges. 3. Discussion An evolution of a STEM distance education program Missouri University of Science and Technology (S&T) has one of the most STEM intensive curriculums in the nation, with over 90 percent of its student body in STEM and business. Only one other university in the USA has a greater concentration of students majoring in STEM degrees. With that said, distance education was initially viewed as impractical if not impossible. Students were required to do hands-on laboratory work or to participate in highly interactive theorem/proof courses. Distance education was relegated to a few courses in a few degrees for which the content was appropriate. The rst step toward offering distance courses was to provide parallel satellite courses at other locations, often using adjunct professors who had primary employment in an industrial organization. Students could participate in lectures on theory and

Collaborative international education 47

METJ 6,1

48

the satellite locations provided access to labs as needed. Alternatively, campus professors traveled to remote sites to present the courses. A primary concern throughout this process was ensuring that the quality of the courses offered was as high as the quality of the on-campus courses. Maintaining identical syllabi and comparing assignment and test results of the off-campus students with those of the on-campus students often established the desired levels of quality. This model seemed to work effectively and it provides guidelines for later developments as well. It is still used to this day via an engineering education center about one hundred miles from the main campus. As electronic capabilities for transmitting course presentations improved, many graduate courses transitioned to a mode of broadcasting the on-campus course to students located remotely. These synchronous presentations ensured that the course presentations were identical for both groups of students, but provided some challenges in handling assignments and examinations. With improvements to the internet, emailing assignments to the on-campus professor from remote students became commonplace. Examinations were often handled by enlisting proctors at remote sites who could call-in with student questions during the examinations, if needed. The synchronous nature of these initial offerings was sometimes broken by the need for remote students to listen to courses at times other than the time they were broadcast. This was especially true for professionals whose employment required them to travel extensively or for courses whose offering time was inconvenient for employed professionals , e.g. for courses offered during the daytime hours on the main campus. Further, some of the remote sites started to be located in different time zones, leading to increasing asynchronous presentations. This made it more difcult for remote students to get timely answers to questions that arose during the lectures, since such questions had to be submitted to the professor via e-mail and answered at a time later than the time the questions arose. As time went on, more and more of the distant students tended to be located independently, which meant that proctors for examinations needed to be enlisted on an individual basis. The most common solution for this was to enlist the students manager at the students place of employment, since both manager and employee had a stake in the quality of the course. In cases where this was impractical, local university testing centers or libraries were often able to supply proctoring services for examinations. This asynchronous, on-demand, style of course offering, though, was advantageous to the university in being able to attract excellent students from a world-wide audience, and to the students, who could take advantage of excellent courses from a high-quality university. So, we can sum up the model that evolved as effective and advantageous to both students and the university, but with challenges in arranging for timely interaction to answer student questions and with challenges in arranging for examinations. E-learning technology and content evolves with distance education As the need for the support of distance education grew, so did the technology on-campus; however, it is difcult to say which came rst. As with many academic institutions, S&T has its share of techno-advocates (a recently coined phrase). Perhaps the rst major tool to support both on-campus and off-campus education was the LMS Blackboard. The adoption of the LMS was driven by an on-campus research center called the Instructional Software Development Center (ISDC) that later evolved into the Center for Technology-Enhanced Learning (CTEL). In many ways it could be

considered a techno-advocate idea that was accepted only by the early-adopters. However, problems with the performance of the system and the need for training of the faculty led to a slow integration into campus standard practice. Meanwhile the growing distance education had a need for content delivery and management, as do most classes; however, options were limited for distant studies. Faculty was under the pressure to e-mail course material, create listservs, nd proctors for examinations and so forth; that is, much of the functionality encapsulated in an LMS. Hence, users of the technology to deliver a distant course soon found themselves setting an example for campus. With recent releases, the LMS has become a staple element of campus courses, as well. This discussion about the LMS is worthwhile because it demonstrates the inter-relationship between on- and off-campus education. Many technologies brought to campus to facilitate distance learning are now considered standard for on-campus use. Web-Ex is now used in collaborations across great distances, the teleconferencing rooms are in high demand, and Smart boards and podiums (originally used in the distance classrooms only) appear in almost every classroom. While e-learning technology may be just a tool for distance education, it is a tool that gets great campus exposure. Not all technology and distance education marriages have gone smoothly without some accommodations. A prime example of that resides in the Information Science and Technology (IST) program concerning the Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) classes. These classes are heavy users of SAP, a complex and very large software system. It is expensive to buy the licenses even for a limited number of seats. The software resided in a dedicated laboratory, making distance sections a challenge. After much trial and error and excessive ulceration, the campus IT department implemented a virtual license server. On-campus, this means that students can use the software in any computer-learning center. For distant students, access to the software has become feasible. While this server was original put in place for the distance program, it is being used by a number of other software systems. Most of these, like SAP, are highly specialized programs for use in upper-level courses in engineering or science. Again, distance education and technology drive growth together. It will be argued shortly that this is also a course for university program marketing, that distance education opens doors of opportunity other than those of technology. A model of international collaboration Several years ago S&T entered into an agreement with American National College of Sri Lanka (ANC) to offer the S&T IST degree there. This degree was selected from the campus offerings because the international students value highly technical degrees with much application. Looking over the STEM degrees from this region of the world, students favor programs that are composed almost exclusively of the science and technology classes apropos for the degree. From the US perspective, their degrees have essentially minimal general education and many technical electives. However, as the global marketplace evolved, the realization developed that there are needs for success other than strictly technological. It should be noted that Missouri S&T presently offers two undergraduate degrees in the Business and Information Technology (BIT) department: a B.S in Business and Management Systems and a B.S. in IST. Undergraduate students in IST focus primarily on the use and applications of computing systems, but they also take

Collaborative international education 49

METJ 6,1

50

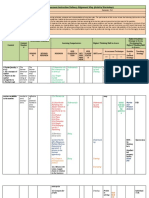

common business topic courses including management and organizational behavior, nancial accounting, corporate nance, and marketing (Elrod et al., 2009). So, both business and technical courses would be required. The rationale for this mixture of requirements is the belief that, in a society that is evolving into more and more dependence on technology in the business workplace, it is extremely important for information technology graduates to understand business concepts (Elrod et al., 2009). In offering the single Missouri University of Science and Technology IST degree in Sri Lanka, four main areas would be needed: general education, business, IST, and free electives. ANC had already been offering a business degree, in collaboration with two US Universities. The new IST degree would be able to utilize these existing relationships (and the quality control that had already been established for them) in order to provide two of the areas. Patten University had been offering general electives and these general electives met quality standards. Northwood University had been offering business core courses, again with good quality. Missouri S&Ts IST program would need to offer the IST core and elective courses, and S&Ts Computer Science department would be able to teach additional elective courses, building a technology-heavy degree (Figure 1 and Table I). All three universities work with ANC to hire faculty in Sri Lanka appropriate for their degree. Each of these universities takes its own steps to ensure the quality

Figure 1. Structure of Missouri S&T degree in Sri Lanka

Spring 2010 (15 February-13 May) IST50 CMPSC53 CMPSC54 Summer 2010 (24 May-12 August) IST51 CMPSC153 Fall 2010 (20 September-16 December) IST151 IST 231 CMPS128 Spring 2011 IST233 IST286 CMPSC253 IST50 CMPSC53 CMPSC54 Summer 2011 ERP 246 IST241 IST243 IST51 CMPSC153 Fall 2011 BUS397 IST223 IST 353 IST151 ERP246 CMPS128 Spring 2012 BUS398 IST 321 IST 361 IST233 IST286 CMPSC253 IST50 CMPSC53 CMPSC54

Information systems Introduction to programming Introduction to programming laboratory Implementation of IS I Data structures I Implementation of IS II Computing internals and operating systems Discrete mathematics for computer science Networks and communications Web & new media design & development Data structures II Information systems Introduction to programming Introduction to programming laboratory Intro to ERP E-Commerce Systems analysis Implementation of IS I Data structures I Senior design I Database management Modular software systems in java Implementation of IS II Intro to ERP Discrete mathematics for computer science Senior design II Network performance design and mgmt Information systems project management Networks and communications Web & new media design & development Data structures II Information systems Introduction to programming Introduction to programming laboratory

Collaborative international education 51

Table I. Example of course sequencing to organize progression of cohorts

of the courses they offered. However, the B.S. degree would be from Missouri S&T. Initially, there were minimal concerns about these arrangements, given that both Northwood and Patton Universities had been successfully offering in Sri Lanka most of their courses for a number of years. In many respects these arrangements were similar to having students transfer to Missouri S&T from these universities in the USA. The Missouri S&T admissions team worked out transfer agreements with the Universities to get all the paperwork into place. Be it noted that we are aware of a number of US Universities that have campuses overseas, as well as a number of US Universities that have exchange programs with universities in other countries. However, we are not aware of other programs

METJ 6,1

like the one described above, which blends extensive distance education with the previously-established programs between ANC, Patten, and Northwood, nor have we discovered any literature which describes such a collaboration. Clearly, future work is appropriate to determine whether the model we have developed is really unique or merely a copy of something similar. Challenges in implementation Offering a degree coordinating three universities across at least four departments is not without its challenges. This new approach would, however, provide some aspects that would lead to broader opportunities in traditional markets, if all issues and concerns could be resolved successfully, thus providing Missouri S&T with a wider market for courses. Initially, it was planned to have the local university work with Missouri S&T to hire professors to teach the courses in the IST program, giving them a great amount of autonomy, but concerns from the accrediting agency led to an alternate approach, utilizing distance education in an expanded role. It was decided to provide the courses as broadcasts of on-campus sections, but to a class of students in Sri Lanka. This was to ensure that academically qualied people, as deemed by the accreditation agency, would be teaching the courses. This was an unforeseen circumstance and has heavily involved S&T in the hiring process. Another issue is that Sri Lankan classes meet on a trimester system whereas S&T is a semester campus. This means that classes would meet on a different calendar schedule and would utilize the broadcasts, but with a local facilitator, who would also collect assignments and give examinations, then grade them and report grades. But this process would be asynchronous to what was happening in Missouri. The facilitator would also be in class to answer any questions and would stay in touch with the Missouri S&T professor to monitor student performance. All assignments and examinations would be identical to the ones used on the Missouri S&T campus. This process has largely overcome two of the challenges of the distance model: the use of an on-site well-qualied professor in the classroom means that student questions can be answered in a timely manner. Further, monitoring exams is not an issue, either. Quality is monitored by the S&T professor via a review of sample homework assignments and examinations. These samples are supplied either electronically or via a courier service and the S&T professor can validate that the grading is being done consistently with the grading for students at S&T. Learning outcomes are also measured exactly the same way as on the home campus, with submission of documents to the evaluation teams for review. The goal is that the remote students will be treated exactly like on-campus students and will meet the same standards. Cohorts of Sri Lankan students enter the program at regular intervals. This is important as the funds and resources are not available to offer all courses needed on both campuses at all times. It was a challenge to synchronize all the campuses involved so as to ensure the students of ANC could graduate at the appropriate time. An example schedule is shown in Table I. Given that the calendars are out of sync, careful attention had to be given to semester boundaries, such as the break between fall and spring. Another issue in this regard is that S&T does not have an extensive summer program; yet ANC routinely teaches in the summer. This meant that spring and fall offerings from the previous academic year needed to be recreated.

52

Another unforeseen issue was the demand of the distance classrooms on-campus. These rooms are equipped with at least Web-Ex and as much as a full video studio. It has been the policy of S&T that only upper level courses (primarily for Master students) would be taught in a distance room. This was to conserve resources. However, the Sri Lanka program required S&T to offer undergraduate courses. This needed approval at the highest levels and resulted in heavy negotiation with administration. The planning of the schedule for the distance room involved the Registrars ofce and compromises were formed. A further complication in this matter was that no computer-equipped classroom was also a distance room. Many of the undergraduate IST classes use computers extensively during lectures and laboratories. To resolve this issue, the Vice-Provost of Global Learning invested in supplying one of the large computer learning classrooms at S&T with Web-Ex that was monitored and managed by the Video Communication Center. Now that a room was in place, it was necessary to ensure that the Sri Lanka sections got scheduled in that room. This was not something automatically done by the registrar; again, compromises were required. The Missouri S&T professors were utilizing the Blackboard course management tools, but the offset timeframes of lecture offerings meant that timing of material being made available to students would differ signicantly. This problem was solved by creating separate sections for each class. Both the Missouri S&T Professor and the local facilitator were able to access these materials. Generally, the materials were placed into the Blackboard sections based on the US date and time availabilities and the local facilitator would modify the dates and times to t the local lecture timeframes. In some of the courses, these materials were quite extensive and spreadsheets of what should be appearing when (organized by lecture number) were created to aid in this management process. A nal issue involves funding and compensation. Ultimately a program like the collaboration with Sri Lanka is created to increase revenue for the university. The expenses of the distance program for the traditional student body were paid for by higher tuition rates and out of state fees. For various reasons, the arrangement with Sri Lanka is that S&T would receive a at fee per student enrolled in the program. This money would then be divided across the Global Learning, administrative, and ultimately the BIT department. By the time the funds reach the department level, there is very little available to compensate the professor for his or her time, leaving the faculty with the feeling they are doing extra work for no recognition or salary. This is a major human relation problem. Ultimately, this program sees its primary upside potential to be Sri Lankan students who choose to come to the S&T campus to nish their degrees and/or continue for graduate school. If a reasonable percentage of students make the transition, then the revenue back to the department is signicant and could potentially create competition to teach the Sri Lanka classes. Reections on the model and the future The model has thus evolved to utilize distance education extensively, but with an on-site professor to provide rapid student interaction and help. In many ways, it seems to be the best way that distance education could be presented it provides the advantages to the university of being able to attract excellent students from a world-wide audience and

Collaborative international education 53

METJ 6,1

54

to the students of being able to take advantage of excellent courses from a high-quality university, as described earlier. It overcomes the challenges involved with student interaction and with giving exams. At the same time, there has been no effort to try to evaluate whether the model is as good as it can be. Clearly, future work should focus on this kind of evaluation and on what kind of modications might be tried to further improve the model. Now that this new approach and the techniques for handling it have been worked out, how does it provide for new approaches for Missouri S&T in marketing and managing course offerings to its traditional US markets? First, consider the aspect of blended offerings from multiple universities. Although transfer agreements and transfers among universities and colleges have been normal practice for a long time, a designed approach for multiple universities to each offer courses in areas where they have special expertise and to team their expertise for degree offerings is not yet normal practice in the USA. For Missouri S&T, this experience has provided incentive to offer to team initially with other Universities within the Missouri system of universities and to utilize this style of central courses with local facilitators. Concerns about different school year calendars can be overcome by creation of multiple class material distribution sections, as was developed for the international collaborative experience. Second, the expertise of professors in performing for broadcast lectures has been broadened from graduate courses to all courses. Since a broadcast lecture generally requires more careful preparation, it seems that this new normality will lead to an increase in the level of professor preparation skills. Third, the on-campus students are very aware of the fact that each class is being broadcast and that questions directed to them in class will be captured in the broadcast. Anecdotally, professors seem to believe that this has led to an increase in student attentiveness in class. However, students who utilize the distance materials are expected to pay the additional fee for a distance course, and this is a limiting factor. 4. Conclusion Enrollments are dwindling in most regions of the USA. State funding is less certain than it used to be. On the other hand, the number of available students in the Asian market is increasing. They know that US schools offer excellent education; yet how is that excellence brought to students half-a-world away? This is a question revolutionizing modern education. The degree program in Sri Lanka is a new horizon for Missouri S&T, and perhaps many other schools. It is not without its complexities, but it is hoped that this article effectively shared the experience, the obstacles encountered, and the solutions that were found.

References Brancheau, J. and Wetherbe, J. (1994), Understanding Innovation Diffusion Helps Boost Acceptance Rates of New Technology, Dryden Press, Orlando, FL. Bray, M. and Lee, W.O. (2001), Education and Political Transitions in East Asia: Diversity and Commonality, Comparative Education Research Centre, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

Cesarone, B. (2003), Using technology in the classroom to foster student learning, Childhood Education, Vol. 79 No. 5, pp. 329-31. Cheese, P. (2003), What keeps universities from embracing e-learning?, Learning and Training, November 5. Compora, D.P. (2003), Current trends in distance education: an administrative model, Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, Vol. 6 No. 2. Eisenbarth, G. (2003), The online education market: much is at stake for institutions of higher education, On the Horizon, Vol. 11 No. 3, pp. 9-15. Elrod, C., Flachsbart, B. and Kehr, W. (2009), Improving student employability by embedding marketing concepts in information science and technology courses, Issues in Information Systems, Vol. X No. 1, pp. 155-66. Feng, R. and Morrison, A. (2003), East versus west: a comparison of online destination marketing in China and the USA, Journal of Vacation Marketing, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 43-56. Gosen, J. (2003), A model for online education delivery and a look at online delivery effectivenes, Developments in Business Simulations and Experiential Learning, Vol. 30, pp. 279-87. Guri-Rosenblit, S. (2005), Distance education and e-learning: not the same thing, Higher Education, Vol. 49 No. 4, pp. 467-93. Hara, N. (1999), Students frustrations with a web-based distance education course, First Monday, Vol. 4 No. 12. Hilgers, M.G., Hall, R. and Buechler, M. (2004), Design and development considerations of a learning object repositor, Proceedings of the Eleventh Americas Conference on Information Systems, Omaha, NE, pp. 635-40. Howard, C., Schenk, K. and Discenza, R. (2004), Distance Learning and University Effectiveness: Changing Educational Paradigms for Online Learning, Information Science Publishing (Idea Group Inc.), Hershey, PA. Husmann, K. and Miller, M. (2001), Improving distance education: perceptions of program administrators, Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, Vol. IV No. 1, pp. 66-89. Kirkwood, A. and Price, L. (2006), Adaptation for a changing environment: developing learning and teaching with information and communication technologies, International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning, Vol. 7 No. 2. Koontz, F.R., Li, H. and Compora, D.P. (2006), Designing Effective Online Online Instruction-A Handbook for Web-Based Courses, Rowman & LIttleeld Education, Oxford. Kunstler, B. (2005), The hothouse effect: a model for change in higher education, On the Horizon, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 173-81. Larsen, R.J. and Diener, E. (2001), Emotional response intensity as an individual difference measure, Journal of Research in Personality, Vol. 21, pp. 1-39. Lenn, M. (2000), Higher education and the global marketplace: a practical guide to sustaining quality, On the Horizon, Vol. 8 No. 5, pp. 7-10. Mellow, G.O. and Woolis, D.D. (2010), Teetering between eras: higher education in a global, knowledge networked world, On the Horizon, Vol. 18 No. 4, pp. 308-19. Moore, M. and Kearsley, G. (1996), Distance Education: A Systems View, Wadsworth Publishing, Belmont, CA. Morrison, J. (2003), US higher education in transition, On the Horizon, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 6-10.

Collaborative international education 55

METJ 6,1

56

Njenga, J.K. and Henry, L. (2010), The myths about e-learning in higher education, British Journal of Educational Technology, Vol. 41 No. 2, pp. 199-212. Shiratuddin, N. and Landoni, M. (2003), A usability study for promoting econtent in higher education, Educational Technology & Society, Vol. 6 No. 4, pp. 112-24. Teichler, U. (2004), The changing debate on internationalisation of higher education, Higher Education, Vol. 48 No. 1, pp. 5-26. Wellington, W., Hutchinson, D. and Faria, A.J. (2005), Using the internet to enhance course presentation: a help or hindrance to student learning, Developments in Business Simulations and Experiential Learning, Vol. 32, pp. 364-71. Wilfred, L., Hall, R., Hilgers, M.G., Leu, M., Hortenstine, J. and Walker, C. (2004), Training in affectively intense virtual environments, Proceedings of the AACE E-Learn Conference, pp. 2233-40. About the authors Dr Michael G. Hilgers is a Professor of Information Science and Technology as well as the Associate Chair of the Business and Information Technology Department at the Missouri University of Science & Technology. He earned his PhD at Brown University. Over the last decade he has pursued educational technology in a variety of roles. He was the Director of both the Instructional Software Development Center and the Center for Technology-Enhanced Learning. He has served on the Board of Directors of the Center for Education, Research, and Innovation. Dr Hilgers has had extensive funding to develop virtual environment training systems and other information-based learning systems. His recent research interests include applications of mathematical models of information to a variety of settings including human-computer interaction. Dr Barry B. Flachsbart is a Professor in Information Science and Technology within the Department of Business and Information Technology at the Missouri University of Science and Technology (formerly University of Missouri-Rolla UMR). He earned his PhD at Stanford University and has had an extensive, 30 plus year career in industry prior coming to academia. He has worked at McDonnell Douglass and Union Pacic Technologies, serving in many upper-level management roles. His current research interests include project management and large database systems. He has also published extensively in the areas of computer applications, manufacturing process design, and articial intelligence. Dr Cassandra C. Elrod is an Assistant Professor of Management in the Department of Business and Information Technology at the Missouri University of Science and Technology (formerly University of Missouri Rolla). She received her PhD in Engineering Management from the University of Missouri Rolla. Her research interests include quality management, lean enterprise, higher education, project management and process control. Dr Cassandra C. Elrod is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: cassa@mst.edu

To purchase reprints of this article please e-mail: reprints@emeraldinsight.com Or visit our web site for further details: www.emeraldinsight.com/reprints

You might also like

- Oral Defense Script FinalDocument4 pagesOral Defense Script FinalManuel Dela Cruz67% (6)

- Guide To CMI Level 7 Stratgic Management and Leadership QualificationsDocument2 pagesGuide To CMI Level 7 Stratgic Management and Leadership Qualificationskim.taylor5743No ratings yet

- Positional Words Lesson PlanDocument1 pagePositional Words Lesson Planapi-384643701No ratings yet

- Alphabet Flashcards 9up PDFDocument9 pagesAlphabet Flashcards 9up PDFAnonymous oLaVyPyNo ratings yet

- E-Learning Focus of The ChapterDocument10 pagesE-Learning Focus of The ChapterGeorge MaherNo ratings yet

- Use of ICT and Student Learning in Higher Education:: Challenges and ResponsesDocument19 pagesUse of ICT and Student Learning in Higher Education:: Challenges and ResponsesDayna DamianiNo ratings yet

- Education and TechnologyDocument10 pagesEducation and TechnologymusamuwagaNo ratings yet

- 130417-Barrie-Todhunter-RS-REVIEW-v01 BTDocument31 pages130417-Barrie-Todhunter-RS-REVIEW-v01 BTCedie YganoNo ratings yet

- 5 Assumptons OJDLA PDFDocument7 pages5 Assumptons OJDLA PDFdaveasuNo ratings yet

- s10639 019 09886 3 PDFDocument24 pagess10639 019 09886 3 PDFKokak DelightsNo ratings yet

- Identifying Success in Online Teacher Education and Professional DevelopmentDocument16 pagesIdentifying Success in Online Teacher Education and Professional DevelopmentMohammad shaabanNo ratings yet

- Preparing For The Digital Educationt PDFDocument235 pagesPreparing For The Digital Educationt PDFBruno massinhanNo ratings yet

- Contextual Factors That Sustain Innovative Pedagogical Practice Using Technology An International StudyDocument17 pagesContextual Factors That Sustain Innovative Pedagogical Practice Using Technology An International StudyLinda PertiwiNo ratings yet

- 1892 14278 1 PBDocument287 pages1892 14278 1 PBGustavo MouraNo ratings yet

- Academic Staff Perceptions of Ict and Elearning A Thai He Case StudyDocument10 pagesAcademic Staff Perceptions of Ict and Elearning A Thai He Case StudyI Wayan RedhanaNo ratings yet

- Student Retention in Higher Education What Role For Virtual Learning EnvironmentsDocument11 pagesStudent Retention in Higher Education What Role For Virtual Learning EnvironmentsAndrea GranadosNo ratings yet

- E-Learning Developments and ExperiencesDocument14 pagesE-Learning Developments and Experiencesorcilacamas354No ratings yet

- 1840-Article Text-5786-1-10-20140421 PDFDocument25 pages1840-Article Text-5786-1-10-20140421 PDFSarim AqeelNo ratings yet

- E-Learning Challenges Faced by Academics in Higher Education: A Literature ReviewDocument11 pagesE-Learning Challenges Faced by Academics in Higher Education: A Literature ReviewTaregh KaramiNo ratings yet

- Academic Cheating in Higher Education The Effect o PDFDocument5 pagesAcademic Cheating in Higher Education The Effect o PDFGuteNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Technology in SchoolsDocument8 pagesLiterature Review On Technology in Schoolsc5eakf6z100% (1)

- Attitude Towards E-Learning - The Case of Mauritian Students in Public TeisDocument16 pagesAttitude Towards E-Learning - The Case of Mauritian Students in Public TeisGlobal Research and Development ServicesNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Information Technology in EducationDocument11 pagesLiterature Review On Information Technology in EducationaflsgzobeNo ratings yet

- DERECHE GROUP - Chapter 123.Document14 pagesDERECHE GROUP - Chapter 123.MARITES M. CUYOSNo ratings yet

- Internet and Higher Education: Patsy Moskal, Charles Dziuban, Joel HartmanDocument9 pagesInternet and Higher Education: Patsy Moskal, Charles Dziuban, Joel HartmanTri FaujiNo ratings yet

- Blended-Learning in Tvet For Empowering Engineering Students' With Technological Innovations: A Case of BangladeshDocument15 pagesBlended-Learning in Tvet For Empowering Engineering Students' With Technological Innovations: A Case of Bangladeshtamanimo100% (1)

- Faculty Perceptions of Distance Education Courses: A SurveyDocument8 pagesFaculty Perceptions of Distance Education Courses: A SurveyCustodio, Al FrancesNo ratings yet

- Perspective and Challenges of The Students On Modular Learning ApproachDocument13 pagesPerspective and Challenges of The Students On Modular Learning ApproachNim RowelaNo ratings yet

- E-Learning: The Student Experience: Jennifer Gilbert, Susan Morton and Jennifer RowleyDocument14 pagesE-Learning: The Student Experience: Jennifer Gilbert, Susan Morton and Jennifer RowleyNurul Amira AmiruddinNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Learning Styles On Learners in E-Learning Environments An Empirical StudyDocument5 pagesThe Influence of Learning Styles On Learners in E-Learning Environments An Empirical StudyMohamedNo ratings yet

- Emmanuel Eng150 Document Annotated Bib BLANK TEMPLATEDocument11 pagesEmmanuel Eng150 Document Annotated Bib BLANK TEMPLATEda xzibitNo ratings yet

- Technological Changes in Student Affairs Administration: Chapter TwelveDocument13 pagesTechnological Changes in Student Affairs Administration: Chapter TwelveRyan Michael OducadoNo ratings yet

- Online Learning in Higher Education: Exploring Advantages and Disadvantages For EngagementDocument14 pagesOnline Learning in Higher Education: Exploring Advantages and Disadvantages For EngagementAfnan MagedNo ratings yet

- Power Distance Literature ReviewDocument6 pagesPower Distance Literature Reviewakjnbowgf100% (1)

- A Framework For Transition Supporting Learning To-3Document16 pagesA Framework For Transition Supporting Learning To-3angle angleNo ratings yet

- Cover Sheet: Online Learning and Teaching (OLT) Conference 2006, Pages Pp. 21-30Document12 pagesCover Sheet: Online Learning and Teaching (OLT) Conference 2006, Pages Pp. 21-30Shri Avinash NarendhranNo ratings yet

- 8.blended .FullDocument14 pages8.blended .FullTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Midtermedit 5370Document10 pagesMidtermedit 5370api-236494955No ratings yet

- Reserts ProposalDocument4 pagesReserts ProposalachuchutvwellNo ratings yet

- Accessible Online Learning - A Preliminary Investigation of Educational Technologists' and Faculty Members' Knowledge and SkillsDocument14 pagesAccessible Online Learning - A Preliminary Investigation of Educational Technologists' and Faculty Members' Knowledge and SkillsPatrick Lowenthal (Boise State)No ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1 in RESEARCHDocument8 pagesCHAPTER 1 in RESEARCHDencie C. CabarlesNo ratings yet

- Research Thesis CharingDocument19 pagesResearch Thesis CharingDanica RicaldeNo ratings yet

- Blended Learning in Computing Education: It 'S Here But Does It Work?Document22 pagesBlended Learning in Computing Education: It 'S Here But Does It Work?Rafsan SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Thesis 1.1 TrialDocument17 pagesThesis 1.1 Trialmark angelo mamarilNo ratings yet

- STI ThesisDocument12 pagesSTI ThesisKurt Francis Hendrick S. PascualNo ratings yet

- EJ1332422Document11 pagesEJ1332422Loulou MowsNo ratings yet

- FarrDocument20 pagesFarrJGONZ123No ratings yet

- Globalization in MathematicsDocument11 pagesGlobalization in MathematicsArianne Rose EspirituNo ratings yet

- Sample ResearchDocument22 pagesSample ResearchZachary GregorioNo ratings yet

- Article 1 FortechprojectDocument8 pagesArticle 1 Fortechprojectapi-281080247No ratings yet

- Redesigning Teaching Practices in Higher Education Amidst Pandemic: The Case of Technologically Challenged InstructorsDocument18 pagesRedesigning Teaching Practices in Higher Education Amidst Pandemic: The Case of Technologically Challenged InstructorsShella Mae LozadaNo ratings yet

- Blended Learning in Higher EducationDocument14 pagesBlended Learning in Higher EducationEen Nuraeni100% (1)

- Wingate Doing Away With Study SkillsDocument15 pagesWingate Doing Away With Study SkillsChompNo ratings yet

- EJ880095Document8 pagesEJ880095jeimperialNo ratings yet

- Critical - Success Online EducationDocument8 pagesCritical - Success Online EducationTofucika Luketazi100% (2)

- QUANTITATIVE RESEARCH Barriers To Learning in Distance EducationDocument6 pagesQUANTITATIVE RESEARCH Barriers To Learning in Distance EducationJiennie Ruth LovitosNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Adult Learners' Decision To Drop Out or Persist in Online LearningDocument12 pagesFactors Influencing Adult Learners' Decision To Drop Out or Persist in Online LearningMaya CamarasuNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature The Importance of Science EducationDocument6 pagesReview of Related Literature The Importance of Science EducationRD BonifacioNo ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature The Importance of Science EducationDocument6 pagesReview of Related Literature The Importance of Science EducationRD BonifacioNo ratings yet

- Student's Perception Towards The Efficacy of LMS During Distance LearningDocument23 pagesStudent's Perception Towards The Efficacy of LMS During Distance LearningRaquel ValentinNo ratings yet

- Blending ModuleDocument12 pagesBlending ModuleMohamad Siri MusliminNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1-3Document4 pagesChapter 1-3Nguyễn Thiện PhúcNo ratings yet

- Leadership in Continuing Education in Higher EducationFrom EverandLeadership in Continuing Education in Higher EducationNo ratings yet

- Changes in the Higher Education Sector: Contemporary Drivers and the Pursuit of ExcellenceFrom EverandChanges in the Higher Education Sector: Contemporary Drivers and the Pursuit of ExcellenceNo ratings yet

- Media in Information Literacy DLLDocument3 pagesMedia in Information Literacy DLLAngelie Pasag GarciaNo ratings yet

- Lena Archer Jarred Wenzel Curriculum Ideology AssignmentDocument9 pagesLena Archer Jarred Wenzel Curriculum Ideology Assignmentapi-482428947No ratings yet

- Discourse Analysis LECTURE 1Document4 pagesDiscourse Analysis LECTURE 1Sorin Mihai Vass100% (1)

- Annual Action Plan of SPGDocument4 pagesAnnual Action Plan of SPGjack jack100% (2)

- Math in 2025Document223 pagesMath in 2025fakename129129No ratings yet

- For Teacher'S Continuous Learning and DevelopmentDocument42 pagesFor Teacher'S Continuous Learning and DevelopmentMa Ria LizaNo ratings yet

- Park PaulayDocument202 pagesPark PaulaytrabajosicNo ratings yet

- Word Origin: Practice Tests ONE - Prepare For MaRRS Spelling Bee Competition ExamDocument47 pagesWord Origin: Practice Tests ONE - Prepare For MaRRS Spelling Bee Competition ExamDebashis Pati100% (2)

- Department of MathematicsDocument31 pagesDepartment of MathematicsmcdabenNo ratings yet

- Key Concepts of Curriculum (Part 2)Document13 pagesKey Concepts of Curriculum (Part 2)Angel Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- UTS - Unit 3 Activity - Setting SMART GoalsDocument4 pagesUTS - Unit 3 Activity - Setting SMART GoalsCHRISTIAN MARTIRESNo ratings yet

- Food Processing DLL 1 Week 1Document6 pagesFood Processing DLL 1 Week 1Maeshellane DepioNo ratings yet

- TMIGLesson 1Document5 pagesTMIGLesson 1Marie ShaneNo ratings yet

- Survey Questionnaires in The Study of Study Habits of StudentsDocument4 pagesSurvey Questionnaires in The Study of Study Habits of StudentsSameer ShafqatNo ratings yet

- Leslie Lio 14Document11 pagesLeslie Lio 14bobleeNo ratings yet

- Let's Read!: A Guide To IELTS ReadingDocument5 pagesLet's Read!: A Guide To IELTS ReadingRafiz SarkerNo ratings yet

- Osmeňa Colleges College of Teacher EducationDocument6 pagesOsmeňa Colleges College of Teacher EducationJojo AcuñaNo ratings yet

- Picto Narrative On District INSET Day 5Document2 pagesPicto Narrative On District INSET Day 5Wendy Arasan100% (3)

- FS1 Activity 16.1Document4 pagesFS1 Activity 16.1Angela RamirezNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document30 pagesChapter 1Sneha AgarwalNo ratings yet

- CIDAM EntrepreneurDocument3 pagesCIDAM EntrepreneurChristian100% (5)

- Lesson Plan Template: What Is Your Favorite Movie?Document4 pagesLesson Plan Template: What Is Your Favorite Movie?api-357843755No ratings yet

- Job Announcement Form NIT RaipurDocument2 pagesJob Announcement Form NIT RaipurMitesh WaghelaNo ratings yet

- Written AnalysisDocument3 pagesWritten AnalysisidaismailNo ratings yet

- Shane R. Brady, PHD, Assistant Professor, University of OklahomaDocument16 pagesShane R. Brady, PHD, Assistant Professor, University of OklahomaGrace Talamera-SandicoNo ratings yet

- Toukball Lesson 1docxDocument8 pagesToukball Lesson 1docxapi-334968025No ratings yet