Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Resistance, Reinhabitation, and Regime Change: David Gruenewald

Resistance, Reinhabitation, and Regime Change: David Gruenewald

Uploaded by

Zayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Resistance, Reinhabitation, and Regime Change: David Gruenewald

Resistance, Reinhabitation, and Regime Change: David Gruenewald

Uploaded by

Zayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Research in Rural Education, 2006, 21(9)

Resistance, Reinhabitation, and Regime Change

Washington State University

Citation: Gruenewald, D. (2006, August 2). Resistance, reinhabitation, and regime change. Journal of Research in Rural Education, 21(9). Retrieved [date] from http://jrre.psu.edu/articles/21-9.pdf Resistance Please linger with me and consider the suggestive power of Walt Whitmans poem, When I Heard the Lear nd Astronomer: When I heard the lear nd astronomer, When the proofs, the gures, were ranged in columns before me, When I was shown the charts and diagrams, to add, divide and measure them, When I sitting heard the astronomer where he lectured with much applause in the lecture-room, How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick, Till rising and gliding out I wanderd off by myself, In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time, Lookd up in perfect silence at the stars. (Whitman, 1955, p. 226) Reciting poetry at a mathematics research symposium is a form of resistance, similar to Whitmans response to the astronomy lecture, which is to rise and glide and wander off. He was a New Yorker, raised in Brooklyn, wrote for and edited several newspapers, went to the opera weekly. Whitman was an experiencer; he sought the thing itselfdirect experiencerather than its second-hand representation. I think we can therefore interpret anyones walking out of this or any lecture as an act or resistance worthy of careful study. We might ask: I wonder where that guy is going? W. S. Merwin, one of Americas greatest living poets, said of poetry, Any work of art makes one very simple

This paper was delivered as the lead keynote address at the Third Research Symposium of the Appalachian Collaborative Center for Learning, Assessment and Instruction in Mathematics (Newark, OH: May 18, 2006). Correspondence concerning this article should be directed to David A. Gruenewald, Department of Teaching and Learning, Washington State University, Pullman, WA 99164-2132. (dgruenewald@wsu.edu)

David Gruenewald

demand on anyone who genuinely wants to get in touch with it. And that is to stop. Youve got to stop what youre doing, what youre thinking, and what youre expecting and just be there . . . however long it takes (Merwin cited in Moyers, 1995, p. 2). Ive been working in public schools and universities for 2 decades now. My observation is that nobody in the system, myself included, seems capable of stopping what they are doing long enough to think deeply about it, to feel deeply about it, to really reect on the total experience. The work of schooling, whether you teach kindergarten, high school math, or philosophy of education, is a treadmill. As soon as you step on it, youre moving. As soon as you step on it, you are pulled by the belt of bureaucracy, by specialization or by research ndings, to move, faster, in a predetermined direction. How can we stop, feel, and think? Theres too much to do. William Carlos Williams (1944), another great American poet, wrote, Its difcult to get the news from poems yet men die miserably every day for the lack of what is found there. (from Asphodel, That Greeny Flower) What I get from Whitmans poem, what I so desperately need, is the strength of conviction to listen to myself, to trust myself enough to stop, feel, think, and act condently in my best interest. I read When I Heard the Lear nd Astronomer as a poem about resistance, resistance to the current reductionism of education to fragmented proofs, gures, charts, diagrams, standards, test scores, best practices, and all the unseen gears of the treadmill: How soon unaccountable I became tired and sick, Till rising and gliding out I wanderd off by myself, In the mystical moist night-air, and from time to time, Lookd up in perfect silence at the stars.

2 Resistance and Math Education

GRUENEWALD withdrew as a helper of the Clearinghouse and sent his story to Educational Researcher. Here, Schoenfeld (2006a) acknowledges that he had some misgivings about working for the Clearinghouse because the agenda is very narrow; I believe that many factors other than those on the [What Works] agenda should be taken into account when examining curricular effectiveness (p. 13). After reading Schoenfelds article, the invited response by the directors of the What Works, and Schoenfelds rejoinder, I believe that it is fundamentally these explicit misgivings about the narrowness of the What Works agenda that led to Schoenfelds silencing, disqualication, and resignation. In his rejoinder, Schoenfeld (2006b) notes: Let me be clear about the stakes involved in this case. The issue here is the suppression of a report that challenges the scientic underpinnings of the current federal policy agenda (p. 23). Im reminded here of the Borg in the television series Star Trek: The Next Generation. The Borg is a technologically advanced learning society that functions through a single collective will. In an eerie parody of globalization, the technologized Borg travel through space in these huge, indestructible cubes, assimilating individuals, communities, and cultures into the collective and destroying all who try to resist. Before they assimilate their victims, they make a show of undeniable force, and they warn, Resistance is futile. The Borg truly do appear unstoppable. Through the show of force, they are able to coerce potential resisters into believing that resistance really is futile. We need not wait for science ction: The numbers of actual resisters to the machine of assimilation are precariously few right now, and dwindling. I sympathize with Schoenfelds experience of being disqualied and admire his small act of academic courage. But as a philosopher and sociologist of education, Im not at all surprised by what happened, and Im also disappointed by the narrowness of Schoenfelds critique of What Works. Part of me wants to say, Welcome to my world, Alan, where what I care about most doesnt qualify for review, not to mention funding. Where what I care about most is disqualied because it doesnt t the ruling regime of scientic effectiveness. Where people are constantly telling me that resisting the regime is futile. Scientic research of the kind embraced by What Works is high status currency in the eld of educational interventions. What remains unknown is how much it is possible to resist, or to intervene with, the policy environment that led to Schoenfelds resignation. Is it possible, for example, to deepen and expand the educational conversation? What impact might such resistance have on the future of education? Or put another way, toward what Borg-like future might the lack of resistance be leading us? Schoenfeld is rightly indignant that his critiques of What Works were censored and suppressed, yet a political

How do we know when, and what, to resist? Alan Schoenfeld, in the March 2006 issue of Educational Researcher, tells a story of resistance that all math educators, and all curriculum specialists, need to consider. I want to use Schoenfelds piece to comment on the necessity and the difculty of resistance in todays climate of schooling and educational research. Schoenfeld titles his story, What Doesnt Work: The Challenge and Failure of the What Works Clearinghouse to Conduct Meaningful Reviews of Studies of Mathematics Curricula. Schoenfeld is a UCBerkeley professor of education who worked as a senior content advisor for the What Works Clearinghouse for its studies of mathematics curricula. An arm of the U.S. Department of Education, the What Works Clearinghouse collects, screens, and identies studies of the effectiveness of educational interventions (italics added, http://www. whatworks.ed.gov). Educational interventions. Its curious phrase for what used to be called teaching. The What Works Clearinghouse is part of the larger attempt by some educational researchers, at the direction of some policymakers to describewith scientic and mathematical precisionbest practices in teaching and learning. In order to qualify for review by the Clearinghouse, a study of educational interventions must be deemed adequately scientic by falling into one of the following three types: randomized experiments, quasi-experiments that use equating procedures, or studies that use the regression discontinuity design. Resistance is a typical, even an expected, response to domination. In this case, domination was the Clearinghouses decision to censor from its publications two essays that it had hired Schoenfeld to write. In these essays, Schoenfeld was critical of the research methodology used to establish educational effectiveness, or what works in middle-level math. Schoenfelds assessment after studying this methodology was straightforward: He simply warned that research reports calling programs effective or ineffective are potentially misleading, and he cited specic examples of how such a report might be misinterpreted. Welcome to research 101. The same could be said of virtually any research, anywhere. Why would the staff at the U.S. Department of Educations What Works Clearinghouse choose to censor this incredibly commonplace caution about educational research? Welcome to politics 101. What seems to have happened is that Schoenfeld told the government something it didnt want to hear: that educational effectiveness is more complicated, and more elusive, than the What Works Clearinghouse has been letting on. After twice refusing to print his critiques, Schoenfeld

RESISTANCE, REINHABITATION, AND REGIME CHANGE sociology of education reform would unveil the suppression of challenges to the reform agenda as everyday acts, taking place everywhere. Suppressing, silencing, and disqualifying challenges to an agenda is, in fact, exactly how a dominant agenda gets built. Let me give an example of how this plays out in educational research. A couple years back, the prestigious Review of Educational Research published an article titled, Comprehensive School Reform and Achievement: A MetaAnalysis (Borman, Hewes, Overman & Brown, 2003). This ambitious study sought to describe the effects on achievement of the most widely implemented school reform models in the U.S. Initially, researchers identied 33 reform models for inclusion in their analysis. In their introduction, however, the authors noted that four models were disqualied from the study in its early stages. The authors decided to explain the reason for the disqualications, and to name the programs rejected, not in the main text, but in the endnotes to their article. I was curious, so I squinted at the ne print in the endnotes and here is what I found: the four models were disqualied because [they] had no quantitative data on their achievement effects from which [the authors] could measure effect size estimates (Borman, Hewes, Overman, & Brown, 2003, p. 210). Again, this kind of disqualication shouldnt really surprise anyone. It is an everyday act everywhere. Disqualications based on statistical (i.e., mathematical) reasoning are what give the Clearinghouse the authority to claim what works. But what was signicant to me about this particular study, what caught my eye in the ne print, was that one of the disqualied reform models was the Foxre Fund, perhaps the oldest and most widely-implemented example of placeconscious, or community-focused, education in the U.S. The point is that in this case, the place-based reform model could not even be included in a comprehensive study of education reform because the study was not calibrated to measure the outcomes of a place-based program like Foxre.1 Schoenfeld critiques the way researchers draw their conclusions from the data. What he doesnt question is the way that entire bodies of dataand entire realms of possibilityare disqualied when they dont t the model, that is, when researchers lack the tools for dealing with them. Ivan Illich wrote, People who have been schooled down to size let unmeasured experience slip out of their hands. This is what I think is happening in educationwere being assimilated, were being schooled down to size. Unmeasured experience is slipping out of our hands as a result, and this slippage is what needs to be resisted. Education should never be thought of as an intervention, though resistance to it must be. To resist is to intervene. Reinhabitation: Mind, Body, Bioregion

What Works. The very name assumes agreement about the nature of the task. What task? What are we supposed to be doing? What Whitman performs in When I Heard the Lear nd Astronomer is the reinhabitation of his own experience. The proofs, the gures, were ranged in columns before him; he was shown the charts and diagrams; the lecturer demonstrated his expertisebut Whitman listened to his body, his intuition, his soul, his heart, his whole being . . . and rising and gliding he wandered off by himself. We might try reinhabiting ourselves, but weve been so assimilated, so schooled with method and discourse, that its hard to return to our senses, to our sense of being alive in the world, to experience ourselves and each other in this moment, and in the places where we rush around together like ants. How are you doing? Fine, busy though. Stop. What is it that we really believe in? What is it that we really want from our work and from our lives? In their focus on relatively trivial matters, many educational researchesespecially curriculum specialiststend to neglect such questions in favor of various kinds of proof. Increasingly I believe that these proofs are cover-ups, distractions from the nagging unspoken feeling that we dont know what the hell we are doing or why. In my teaching and research on education and place, Im constantly coming back to questions of purpose. What am I trying to get at, really? What happened here in this place? Whats happing here in this place? What should happen here in this place? We need to understand where we are and what it is we are trying to accomplish before we can gauge what works. This principle seems obvious to me, and there is a certain logic to it. But questioning our purposes, deliberating in earnest about our aims? Most educators are just too hell-bent on achievement. Poetry makes me stop. Time for another poem. Like Whitmans, this poem is about math, resistance, and reinhabiting the space you are in. Zimmers Head Thudding Against the Blackboard by Paul Zimmer (1999): At the blackboard I had missed Five number problems in a row, And was about to foul a sixth, When the old exasperated nun Began to pound my head against My six mistakes. When I cried, She threw me back into my seat, Where I hid my head and swore That very day Id be a poet, And curse her yellow teeth with this.

For a history of Foxre, see Puckett (1989).

4 The Clock of the Long Now

GRUENEWALD and principals are deemed effective if they produce results quickly. Longitudinal studies are considered long-term if they span a mere ten years, and even this time frame is exceedingly rare in research. The only research methodology with an arguably long-term perspective is historical or philosophical research, yet such work is marginalized as impractical and it is effectively banished from most colleges of education, Ph.D. programs, professional journals, and conferences. What The Clock of the Long Now and the Long Now Foundation (www.longnow.org) represents to me is a way of reinhabiting the time frames that keep us from talking together about our most sacred aims as educators and as human beings. It is a symbol of resistance to the push to produce results in the short term. Resistance to the shortterm press is needed in order to create the time and space to reconsider our aims and to reassess what works. Regime Change Do we need a regime change? Heres a relevant passage from the preamble of the Earth Charter, a multicultural, international peoples treaty available in over 40 languages at www.earthcharter.org: The Global Situation: The dominant patterns of production and consumption are causing environmental devastation, the depletion of resources, and a massive extinction of species. Communities are being undermined. The benets of development are not shared equitably and the gap between rich and poor is widening. Injustice, poverty, ignorance, and violent conict are widespread and the cause of great suffering. An unprecedented rise in human population has overburdened ecological and social systems. The foundations of global security are threatened. These trends are perilousbut not inevitable. I sense an out-of-touch elitism in what is called educational research when I reect on the enormous injustices and atrocities of recent times. What works? According to a 2003 UNESCO report titled Learning to Live Together: Have We Failed? over 180 million people were killed intentionally during the twentieth century. The initiators and perpetrators of these crimes, the report states, are usually people who have spent a great deal of their lives in the education systems of both rich and poor countries (pp. 12-13). The report also says that on September 11, 2001 some 3,000 people were killed in a series of terrorist attacks. But also, on the same day and every day since, some 35,000 children died of hunger and poverty in the world, 7,500 people

Stopping is hard. Our experience of timewhat we have time for and what we dontpretty much denes who we are and what we believe in. Here is how Stewart Brand (1999), author of The Clock of the Long Now, describes our situation: Civilization is revving itself into a pathologically short attention span. The trend might be coming from the acceleration of technology, the short-horizon perspective of market-driven economics, the next-election perspective of democracies, or the distraction of personal multitasking. Some sort of balancing corrective to the short-sightedness is neededsome mechanism or myth that encourages the long view and the taking of long-term responsibility, where the long term is measured at least in centuries. (p. 2) Brands book is a collection of essays on the speeded up nature of time and experience, and on the need to teach ourselves and practice long-term thinking and long-term responsibility. At the heart of the book is a description of a project to build the worlds slowest clock, one that will keep perfect time for the next 10,000 years. Computer designer Daniel Hillis wrote of this project in 1993, I think it is time for us to start a long-term project that gets people thinking past the mental barrier of the Millennium. I would like to propose a large (think Stonehenge) mechanical clock, powered by seasonal temperate changes. It ticks once a year, bongs once a century, and the cuckoo comes out every millennium. (Hillis cited in Brand, 1993, p. 3) The idea behind The Clock of the Long Now is to create an actual working artifact that represents a new way of thinking about time and responsibility. It is an image for a new myth, a reinhabitation of experience and of civilization. Instead of long-term thinking meaning next quarters prots, or next semesters teaching load, or when I retire, or when my kids or their kids kids inherit whatever is left, it means the next 1,000 years or 10,000 years. The cuckoo wont come out until then. The eld of education daily contributes to the pathological rush that Brand and Hillis and many others believe denes our ever more dangerous and destructive civilization. Lets pay attention: We live in a time of re and dust. One need only pick up a newspaper to see that the world is in ames. Meanwhile, high-stakes testing and annual yearly progress put the long term about 9 months out from the start of every school year. Curriculum reforms, teachers,

RESISTANCE, REINHABITATION, AND REGIME CHANGE died of HIV/AIDS, and about 14,000 became infected. The authors of this UNESCO report write: The possibility of learning and teaching [how we might go on] living together depends on the recognition of every one of these problems, the ability of presenting them side by side and on making headway in understanding their specicities and also their interconnectedness. (UNESCO: IBE, p. 91) If you want to experience some creative dissonance, juxtapose these observations about living and learning in the 21st century with the latest educational regulations from No Child Left Behind, or the latest boasts of the What Works Clearinghouse. Here is something else to chew on: A recent Worldwatch (2004, Necessity section) report states, Providing adequate food, clean water, and basic education for the worlds poorest could all be achieved for less than people spend annually on makeup, ice cream, and pet food. What, in this very surreal context, is the meaning of educational effectiveness? What works? To identify as an educational researcher in a world full of violence, injustice, and ecological ruin is, rst of all, a privilege. It strikes me as somewhat bizarre to say it, but it is a privilege to have the economic and social capital needed, and the distance from suffering required, to be able to reect in relative comfort on the worlds problems, to be an interpreter of major crises instead of a victim. An elitist trap that has marked the researcher with pretension and even irrelevance is the tendency not to recognize the privileges that make professional research possible. This is not to say that research doesnt require sacrices, it does, but to acknowledge more particularly that academe has been and remains an enclave of privilege, and further, to suggest that with privilege comes a responsibility to examine and work to transform the structures that maintain interconnected webs of privilege, oppression, violence, and multiple forms of domination and control. Regime change: The Earth Charter aims at the following cultural transformations, among many others: 1. 2. Promote the equitable distribution of wealth within nations and among nations. Eliminate discrimination in all its forms, such as that based on race, color, sex, sexual orientation, religion, language, and national, ethnic or social origin. Demilitarize national security systems to the level of a non-provocative defense posture, and convert military resources to peaceful purposes, including ecological restoration. 4. Transmit to future generations values, traditions, and institutions that support the long-term ourishing of Earths human and ecological communities. Recognize the ignored, protect the vulnerable, serve those who suffer, and enable them to develop their capacities and to pursue their aspirations.

5.

These are the kind of principles that ought to guide our thinking about effectiveness, accountability, or rather, responsibility. An essential part of the work of the researcher, then, at least in the broad cultural sphere of education, is to situate her inquiry, whatever it is, against the background of a larger analysis of culture, identity, difference, conict, and the possibilities for learning to live together in diverse, unequal communities. This constitutes a regime change in a eld that too often refuses to analyze its own assumptions. This is what it means to me to be critical: to develop a deep cultural analysis that might provide the foundation for meaningful action in the work of education. And to do this, I believe we need to resist current trends toward further professionalization and specialization in the eld. We need to resist what works long enough to reect on what matters. In his provocative book, Representations of the Intellectual, the late Edward Said described the pressure of specialization as the greatest threat to the development of the intellectual. Said (1994) wrote, Specialization means losing sight of the raw effort of constructing either art or knowledge; as a result you cannot view knowledge and art as choices and decisions, commitments and alignments, but only in terms of impersonal theories or methodologies. . . . In the end as a fully specialized . . . intellectual you become tame and accepting of whatever the so-called leaders in the eld will allow. Specialization also kills your sense of excitement and discovery, both of which are irreducibly present in the intellectuals make-up. In the nal analysis, giving up to specialization is, I have always felt, laziness, so you end up doing what others tell you, because that is your specialty after all. (p. 77) Said reminds me that intellectual work is deeply personal and political. That it cannot be about following the rules of a system that rewards intellectual conformity, but that it must be a spirited struggle, a raw effort to question, reect, stand up, speak, create, and act, and to do all of these things in the presence of those credentialed experts who may very well look on you and your work disapprovingly.

3.

GRUENEWALD do/ with your one wild and precious life? I cannot stress too much how difcult it is to insert such a question into contemporary discourse about schooling. The corporate takeover of public life is narrowing the possibilities of all our institutions. We are now training teachers, administrators, children and youth to compete and succeed in a global economy that privileges a few at great costs to land and people, to human and nonhuman communities. We are now training teachers, administrators, children and youth to produce better results for a leadership that has lost millions of jobs, accumulated record debts, eroded environmental protection and civil liberties, exacerbated inequities in wealth and power, waged regular war, abandoned the mission of the United Nations, sold out to the corporate media, and that is increasingly out of favor among citizens of every nation. Resistance is by no means futile. To be a researcher capable of resistance, of identifying the need for resistance, is, therefore, to develop an analysis, a critique. The agitating French philosopher Michel Foucault (1988) explains, A critique is not a matter of saying that things are not right as they are. It is a matter of pointing out on what kinds of assumptions, what kinds of familiar, unchallenged, unconsidered modes of thought the practices that we accept rest. . . . I think the work of deep transformation can only be carried out in a free atmosphere, one constantly agitated by permanent criticism. (pp. 154-155) Obviously, though, analysis and critique are not enough to ensure action. As Paulo Freire (1995) insists in Pedagogy of the Oppressed, When a word is deprived of its dimension of action, reection automatically suffers as well; and the work is changed into idle chatter, into verbalism, into an alienated and alienating blah. It becomes an empty word, one which cannot denounce the world, for denunciation is impossible without a commitment to transform, and there is no transformation without action. (p. 68) So I ask myself again, What is it I plan to do with my one wild and precious life? And as a teacher I ask, What is it you plan to do with yours? Finally, to be a researcher is not to isolate oneself, but to nd, create, or open to a community of others with whom you will share it, the journey to acknowledge privilege, work for justice, condemn oppression, and respond to the call that is your one chance to make life wild and precious. bell hooks (1990) calls this community a space of radical openness . . . a margina profound edge. Locating oneself

Said cites the existentialist philosopher Sartre, who said that the intellectual is never more an intellectual than when surrounded, cajoled, hemmed in, hectored by society to be one thing or another, because only then and on that basis can intellectual work be constructed (p. 76). Intellectual work, according to this view, is an act of creative resistance to the pressures of specialization, pressures that are endemic to school and university work. When we can resist what works long enough to reect on what matters, we will experience a regime change. How does one negotiate the pressures of professionalization so as not to become absorbed and assimilated by them? I have argued that to be a researcher is rst a privilege and second a responsibility, the responsibility to acknowledge privilege and to be critical of those structures that maintain privileges at great costs to other individuals, communities, and ecosystems. Third, I believe that to embrace the work of education, to undertake the struggle to create against the pressure to please and achieve, is to respond to an inner call. We need to re-learn how to pay attention to our innermost thoughts and feelings. Resistance is not futile. We need to acknowledge when we are tired and sick, and to rise and glide condently when we need to be replenished. It saddens and angers me to reect on the many ways that schools and universities fail to encourage us to listen to the deep places inside of us where creative people have always found their inspiration. Instead, we are classied, tracked, programmed, and coerced to obey the self-important voices of external authority or peer reviewvoices that chant accountability, achievement, best practice, what works, standardization, rigor, resistance is futile. I quote from the U.S. governments No Child Left Behind website: The new law redenes the federal governments role in kindergarten-through-grade-12 education . . . the new law will change the culture of Americas schools so that they dene their success in terms of student achievement. . . . The rst principle of accountability for results involves the creation of standards in each state for what a child should know and learn in reading and math in grades three through eight. With those standards in place, student progress and achievement will be measured according to state tests designed to match those state standards and given to every child, every year. ( 1-2) Student progress and achievement will be measured according to state tests designed to match those state standards and given to every child, every year: Resistance is futile. The great contemporary poet Mary Oliver asks in her poem The Summer Day, Tell me, what is it you plan to

RESISTANCE, REINHABITATION, AND REGIME CHANGE there, she writes, is difcult yet necessary. It is not a safe place. One is always at risk. One needs a community of resistance (p. 149). References Borman, G., Hewes, B., Overman, L., & Brown, S. (2003). Comprehensive school reform and achievement: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 73, 125-230. Brand, S. (1999). The clock of the long now. New York: Basic Books. Foucault, M. (1988). Politics, philosophy, culture: Interviews and other writings, 1977-1984. New York: Routledge. Freire, P. (1995). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum. hooks, b. (1990). Yearning: Race, gender, and cultural politics. Boston: South End Press. Illich, I. (1971) Deschooling society. New York: Harper & Row. Moyers, B. (1995). The language of life: A festival of poets. New York: Doubleday. Oliver, M. (1992). The summer days. In New and selected poems (p. 94). Boston: Beacon Press. Puckett, J. (1989). Foxre reconsidered: A twenty-year experiment in progressive education. Urban and Chicago, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Said, E. (1994). Representations of the intellectual. New York: Pantheon Books. Schoenfeld, A. (2006a). What doesnt work: The challenge and failure of the What Works Clearinghouse to conduct meaningful reviews of studies of mathematics curricula. Educational Researcher, 35(2), 13-21. Schoenfeld, A. (2006b). Reply to comments from What Works Clearinghouse on What Doesnt Work. Educational Researcher, 35(2), 23. UNESCO International Bureau of Education. (2003). Learning to live together: Have we failed? Geneva, Switzerland: Author. U.S. Department of Education. (2002). Testing for results. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://www. ed.gov/nclb/accountability/ayp/testingforresults.html) Whitman, W. (1955). Leaves of grass. New York: The New American Library. Williams, W. C. (1944). Collected poems: 1939-1962 (Vol. 2). New York: New Directions. Worldwatch Institute. (2004). State of the world 2004: Consumption by the numbers. Williamsportt, PA: Author. Retrieved from www.worldwatch.org/press/ news/2004/01/07 Zimmer, P. (1999). Zimmers head thudding against the blackboard. In M. Anderson & D. Hassler (Eds.), Learning by heart: Contemporary American poetry about school (p. 21). Iowa City, IA: The University of Iowa Press.

You might also like

- State of Content Marketing 2023Document126 pagesState of Content Marketing 2023pavan teja100% (1)

- Martha Nussbaum's Liberal Education Paper PDFDocument16 pagesMartha Nussbaum's Liberal Education Paper PDFSergio CaroNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Conversations: Challenging Habits of ThoughtFrom EverandInterdisciplinary Conversations: Challenging Habits of ThoughtRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- A Critique of Creativity and Complexity PDFDocument73 pagesA Critique of Creativity and Complexity PDFzirpoNo ratings yet

- Maarij Al Lahfan Li Al Taraqi Ila Haqaiq Al IrfanDocument87 pagesMaarij Al Lahfan Li Al Taraqi Ila Haqaiq Al IrfanZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Everythings An Argument NotesDocument4 pagesEverythings An Argument Notesjumurph100% (1)

- Nelson 'Fierce Humanities'Document8 pagesNelson 'Fierce Humanities'mandrade_22No ratings yet

- Political Science Pedagogy: Critical Political Theory and Radical PracticeDocument183 pagesPolitical Science Pedagogy: Critical Political Theory and Radical PracticeTemesgen DestaNo ratings yet

- Science in General Education 2013Document9 pagesScience in General Education 2013JulianNo ratings yet

- Laboratories and Rat Boxes: A Literary History of Organic and Mechanistic Models of EducationFrom EverandLaboratories and Rat Boxes: A Literary History of Organic and Mechanistic Models of EducationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- By Paul Henrickson, PH.DDocument6 pagesBy Paul Henrickson, PH.DPaul HenricksonNo ratings yet

- Anarchy Thesis StatementDocument6 pagesAnarchy Thesis Statementfjcxm773100% (2)

- Principles of Behavior An Introduction To Behavior Theory (Clark L. Hull)Document444 pagesPrinciples of Behavior An Introduction To Behavior Theory (Clark L. Hull)Pablo Villanueva FernándezNo ratings yet

- Full Download Sociology Your Compass For A New World Canadian 5th Edition Brym Solutions ManualDocument19 pagesFull Download Sociology Your Compass For A New World Canadian 5th Edition Brym Solutions Manualcherlysulc100% (30)

- Dynamics of the Contemporary University: Growth, Accretion, and ConflictFrom EverandDynamics of the Contemporary University: Growth, Accretion, and ConflictNo ratings yet

- Adam Podgorecki - Higher Faculties - A Cross-National Study of University Culture (1997)Document206 pagesAdam Podgorecki - Higher Faculties - A Cross-National Study of University Culture (1997)muldri100% (1)

- The Alienated Academic The Struggle For Autonomy Inside The University 1St Ed Edition Richard Hall Full Chapter PDFDocument69 pagesThe Alienated Academic The Struggle For Autonomy Inside The University 1St Ed Edition Richard Hall Full Chapter PDFbaldusboyrie100% (2)

- Compulsory MiseducationDocument65 pagesCompulsory Miseducationapi-3705112No ratings yet

- Greene (2013) .Document11 pagesGreene (2013) .Pattylú Quintana Figueroa100% (1)

- Allsup - Creating An Educational Framework For Popular Music in Public Schools. Anticipating The Second-WaveDocument28 pagesAllsup - Creating An Educational Framework For Popular Music in Public Schools. Anticipating The Second-WaveemschrisNo ratings yet

- Class Matters: A Response To Shiv VisvanathanDocument2 pagesClass Matters: A Response To Shiv VisvanathanSamar SinghNo ratings yet

- Lingua Franca v4.PsDocument6 pagesLingua Franca v4.Pssagret10No ratings yet

- Vivian M May - Pursuing Intersectionality, Unsettling Dominant Imaginaries-Routledge (2015)Document301 pagesVivian M May - Pursuing Intersectionality, Unsettling Dominant Imaginaries-Routledge (2015)Bianca Lopes BritesNo ratings yet

- 2000 Fall McCullybookrevConnectionDocument2 pages2000 Fall McCullybookrevConnectionJohn O. HarneyNo ratings yet

- Schools of Thought: Twenty-Five Years of Interpretive Social ScienceFrom EverandSchools of Thought: Twenty-Five Years of Interpretive Social ScienceNo ratings yet

- Toward A Critical Theory of States The Poulantzas-Miliband Debate After Globalization - Clyde W. BarrowDocument219 pagesToward A Critical Theory of States The Poulantzas-Miliband Debate After Globalization - Clyde W. BarrowKaren Souza da Silva100% (1)

- Democracy's Children: Intellectuals and the Rise of Cultural PoliticsFrom EverandDemocracy's Children: Intellectuals and the Rise of Cultural PoliticsRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Dwnload Full Sociology Your Compass For A New World Canadian 5th Edition Brym Solutions Manual PDFDocument36 pagesDwnload Full Sociology Your Compass For A New World Canadian 5th Edition Brym Solutions Manual PDFhollypyroxyle8n9oz100% (13)

- Lustick Polity Taking Evol Seriously Pol201026a PDFDocument31 pagesLustick Polity Taking Evol Seriously Pol201026a PDFLuis Gonzalo Trigo SotoNo ratings yet

- PSCI 0400 920 DraftsyllabusDocument5 pagesPSCI 0400 920 DraftsyllabusJag uarNo ratings yet

- Good Enough Methods For Ethnographical Research (1) (Luttrell, 2000)Document20 pagesGood Enough Methods For Ethnographical Research (1) (Luttrell, 2000)Saul RecinasNo ratings yet

- Disciplined Mind: What All Students Should UnderstandFrom EverandDisciplined Mind: What All Students Should UnderstandRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (21)

- The Quest For A New EducationDocument17 pagesThe Quest For A New EducationremipedsNo ratings yet

- Keohane Political Science As A Vocation 2009Document5 pagesKeohane Political Science As A Vocation 2009J.C.No ratings yet

- The Value of The Arts in Education: Scholarworks at WmuDocument35 pagesThe Value of The Arts in Education: Scholarworks at WmuJenny jorquinNo ratings yet

- Metodologia em PS - RozinDocument13 pagesMetodologia em PS - RozinjubartijottoNo ratings yet

- Artikel KatzDocument15 pagesArtikel KatzmvbuggenNo ratings yet

- Connolly File - Michigan7 2018 MMMRDocument119 pagesConnolly File - Michigan7 2018 MMMRAndrew TsangNo ratings yet

- Sociology of The AnarchistDocument139 pagesSociology of The AnarchistYusni AzizNo ratings yet

- Paper 1Document19 pagesPaper 1quynhpham.89233020100No ratings yet

- The Alienated Academic The Struggle For Autonomy Inside The University 1St Ed Edition Richard Hall Full ChapterDocument67 pagesThe Alienated Academic The Struggle For Autonomy Inside The University 1St Ed Edition Richard Hall Full Chaptertodd.thompson395100% (8)

- Ability Disability and The Question of PhilosophyDocument8 pagesAbility Disability and The Question of PhilosophyJorge OrozcoNo ratings yet

- Visionary Pragmatism by Romand ColesDocument41 pagesVisionary Pragmatism by Romand ColesDuke University PressNo ratings yet

- Essay-Fredric Jameson, Leonard Green-Interview With Fredric JamesonDocument21 pagesEssay-Fredric Jameson, Leonard Green-Interview With Fredric Jamesonmaryam sehatNo ratings yet

- (Inter) Dependent Learning Learning Is InteractionDocument28 pages(Inter) Dependent Learning Learning Is Interactionjhoracios836318No ratings yet

- Challenging Values - ConflictContradiction and PedagogyDocument15 pagesChallenging Values - ConflictContradiction and PedagogyCameliaGrigorașNo ratings yet

- Political Science As A VocationDocument5 pagesPolitical Science As A VocationNap GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Miller 1998Document4 pagesMiller 1998Katerin ElizabethNo ratings yet

- Literary Criticism Term PaperDocument5 pagesLiterary Criticism Term Paperc5rn3sbr100% (1)

- On Ontological DisobedienceDocument13 pagesOn Ontological DisobedienceRenzoTaddeiNo ratings yet

- Teague - The Value of The Arts in EducationDocument36 pagesTeague - The Value of The Arts in EducationThorin TeagueNo ratings yet

- Oxford University PressDocument3 pagesOxford University PressBehroz KaramyNo ratings yet

- General Introduction To The - Indoctrination Studies - SectionDocument3 pagesGeneral Introduction To The - Indoctrination Studies - Sectionlrc3No ratings yet

- Burawoy (1998) The Extended Case MethodDocument31 pagesBurawoy (1998) The Extended Case MethodnahuelsanNo ratings yet

- The Death of a Scientist: The (self-)annihilation of Modern Scientific CommunityFrom EverandThe Death of a Scientist: The (self-)annihilation of Modern Scientific CommunityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- COMPLICITY ContentsandPrologueDocument6 pagesCOMPLICITY ContentsandPrologueFernanda CardosoNo ratings yet

- BNM Structure 20170817 enDocument1 pageBNM Structure 20170817 enZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Nuclear Power Plant Design AnalysisDocument499 pagesNuclear Power Plant Design AnalysisBharath RamNo ratings yet

- Aerostat Radar SystemDocument3 pagesAerostat Radar SystemZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Hsbcs Guide To Straight Through ProcessingDocument8 pagesHsbcs Guide To Straight Through ProcessingZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Quest For The Red Sulphur by Claude AddasDocument180 pagesQuest For The Red Sulphur by Claude AddasZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-Hadrami100% (4)

- Public Debt Old Bonds FraudDocument1 pagePublic Debt Old Bonds FraudZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Physics BrochureDocument6 pagesPhysics BrochureZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Luminex Sample Business PlanDocument22 pagesLuminex Sample Business PlanZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Trade For Corporates OverviewDocument47 pagesTrade For Corporates OverviewZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- mt798 FAQv2Document7 pagesmt798 FAQv2Zayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Islamic SpiritualityDocument5 pagesIslamic SpiritualityZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Omar Diary of Sultan AhmadDocument333 pagesOmar Diary of Sultan AhmadZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Hsbcs Guide To Straight Through ProcessingDocument8 pagesHsbcs Guide To Straight Through ProcessingVi ZaNo ratings yet

- SWIFT Trade Finance Messages and Anticipated Changes 2015Document20 pagesSWIFT Trade Finance Messages and Anticipated Changes 2015Zayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Esoteric Deviation Text 1Document973 pagesEsoteric Deviation Text 1Abd al-Haqq MarshallNo ratings yet

- 185straight Lines Miscellaneous ExerciseDocument25 pages185straight Lines Miscellaneous ExerciseZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- The Diwan of Ibn ArabiDocument3 pagesThe Diwan of Ibn ArabiZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- CryptologyDocument18 pagesCryptologyZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Autonomous Region in Muslim MindanaoDocument80 pagesAutonomous Region in Muslim MindanaoZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Multi Radar Tracker MRTDocument4 pagesMulti Radar Tracker MRTZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- 1 Extremely Low Expectation 5 Extremely High Expectation Questions 1 2 3 4 5Document1 page1 Extremely Low Expectation 5 Extremely High Expectation Questions 1 2 3 4 5Zayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Eastern.: ADJ - Genetive Masculine Singular AdjectiveDocument3 pagesEastern.: ADJ - Genetive Masculine Singular AdjectiveZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Absolute Determination of The Fast Neutron Fluxes by Using The Flow-Type Manganese Bath MethodDocument8 pagesAbsolute Determination of The Fast Neutron Fluxes by Using The Flow-Type Manganese Bath MethodZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Title 7 Natural Resources and Environmental Control Delaware Administrative Code 1 1100 Air Quality Management Section 1134 Emission Banking and Trading ProgramDocument15 pagesTitle 7 Natural Resources and Environmental Control Delaware Administrative Code 1 1100 Air Quality Management Section 1134 Emission Banking and Trading ProgramZayd Iskandar Dzolkarnain Al-HadramiNo ratings yet

- Stone Houses of Jefferson CountyDocument240 pagesStone Houses of Jefferson CountyAs PireNo ratings yet

- CORE122 - Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human PersonDocument6 pagesCORE122 - Introduction To The Philosophy of The Human PersonSHIENNA MAE ALVISNo ratings yet

- Intensive-Level Survey of The Washington Heights Area of Washington DC.Document128 pagesIntensive-Level Survey of The Washington Heights Area of Washington DC.Envision Adams MorganNo ratings yet

- View Full-Featured Version: Send To PrinterDocument5 pagesView Full-Featured Version: Send To PrinteremmanjabasaNo ratings yet

- AKPI - Laporan Tahunan 2019Document218 pagesAKPI - Laporan Tahunan 2019Yehezkiel OktavianusNo ratings yet

- FA REV PRB - Prelim Exam Wit Ans Key LatestDocument13 pagesFA REV PRB - Prelim Exam Wit Ans Key LatestLuiNo ratings yet

- 2007 AmuDocument85 pages2007 AmuAnindyaMustikaNo ratings yet

- Purposive Communication LectureDocument70 pagesPurposive Communication LectureJericho DadoNo ratings yet

- Check My TripDocument3 pagesCheck My TripBabar WaheedNo ratings yet

- AnnamayyaDocument4 pagesAnnamayyaSaiswaroopa IyerNo ratings yet

- Atlantic Coastwatch: An Era Ending?Document8 pagesAtlantic Coastwatch: An Era Ending?Friends of the Atlantic Coast Watch NewsletNo ratings yet

- Arts 9 Qtr. 3 Final Unit-Learning-PlanDocument15 pagesArts 9 Qtr. 3 Final Unit-Learning-PlanGen TalladNo ratings yet

- Ethics SyllabusDocument5 pagesEthics SyllabusprincessNo ratings yet

- Holy Rosary - Sorrowful MysteriesDocument43 pagesHoly Rosary - Sorrowful MysteriesRhea AvilaNo ratings yet

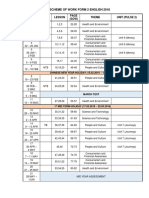

- Scheme of Work Form 2 English 2018: Week Types Lesson (SOW) Theme Unit (Pulse 2)Document2 pagesScheme of Work Form 2 English 2018: Week Types Lesson (SOW) Theme Unit (Pulse 2)Subramaniam Periannan100% (2)

- Modul Berbicara 1Document49 pagesModul Berbicara 1Alif Satuhu100% (1)

- 2.6 Acuna - Norway - NorthernLightsDocument9 pages2.6 Acuna - Norway - NorthernLightssharkzvaderzNo ratings yet

- IA 6 Module 5-Edited-CorpuzDocument15 pagesIA 6 Module 5-Edited-CorpuzAngeline AlesnaNo ratings yet

- Accounting 1 Module 3Document20 pagesAccounting 1 Module 3Rose Marie Recorte100% (1)

- Internship Report-Ashiqul Islam Anik - 114 162 017 - 23APRIL, 22Document56 pagesInternship Report-Ashiqul Islam Anik - 114 162 017 - 23APRIL, 22Selim KhanNo ratings yet

- Cash and Cash Equivalents (Problems)Document9 pagesCash and Cash Equivalents (Problems)IAN PADAYOGDOGNo ratings yet

- LLB102 2023 2 DeferredDocument8 pagesLLB102 2023 2 Deferredlo seNo ratings yet

- Mission - List Codigos Commandos 2Document3 pagesMission - List Codigos Commandos 2Cristian Andres0% (1)

- Illustration For Payback Calculation of AHFDocument7 pagesIllustration For Payback Calculation of AHFAditya PandeyNo ratings yet

- The Acient Eurasian World - Vol. IDocument352 pagesThe Acient Eurasian World - Vol. IIpsissimus100% (1)

- Chapter 2 LAW ON PARTNERSHIPDocument22 pagesChapter 2 LAW ON PARTNERSHIPApril Ann C. GarciaNo ratings yet

- 3 MicroDocument4 pages3 MicroDumitraNo ratings yet

- Green Building: Technical Report OnDocument9 pagesGreen Building: Technical Report OnAnurag BorahNo ratings yet