Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sickness and Freedom

Sickness and Freedom

Uploaded by

sir_joseph_weissman0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

25 views2 pagesThis document discusses the relationship between sickness and freedom. It argues that becoming sick and recovering slowly can be a "fundamental cure for all pessimism." It also states that there are different kinds of pain distinguished not only by intensity and duration, but also by the nature of recovery. Finally, it discusses how the question of health and sickness is a social one and relates to overcoming suffering and the possibility of radical social change and difference.

Original Description:

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document discusses the relationship between sickness and freedom. It argues that becoming sick and recovering slowly can be a "fundamental cure for all pessimism." It also states that there are different kinds of pain distinguished not only by intensity and duration, but also by the nature of recovery. Finally, it discusses how the question of health and sickness is a social one and relates to overcoming suffering and the possibility of radical social change and difference.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as doc, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

25 views2 pagesSickness and Freedom

Sickness and Freedom

Uploaded by

sir_joseph_weissmanThis document discusses the relationship between sickness and freedom. It argues that becoming sick and recovering slowly can be a "fundamental cure for all pessimism." It also states that there are different kinds of pain distinguished not only by intensity and duration, but also by the nature of recovery. Finally, it discusses how the question of health and sickness is a social one and relates to overcoming suffering and the possibility of radical social change and difference.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as DOC, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as doc, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 2

Sickness and Freedom

Joseph Weissman

“…and how much sickness is expressed in the wild experiments and

singularities through which the liberated prisoner now seeks to demonstrate

his mastery over things!”

Human, All Too Human (7)

“To become sick in the manner of these free spirits, to remain sick for a long

time and then, slowly, slowly, to become healthy, by which I mean

‘healthier’, is a fundamental cure for all pessimism… There is wisdom,

practical wisdom, in for a long time prescribing even health for oneself only

in small doses.”

ibid (9)

How should we think the relation of strength of character to the

possibility of a recovery from sickness? First, we ought to remind ourselves

that sickness is not always and only a reaction. After all, a truly positive

outlook does not entail removing or annulling suffering, as of excising a

cancer, but rather the wholesale transmutation of suffering – as of lead to

gold. If there is an alchemical sense to suffering, even to cruelty, then our

outlook on life is no longer a matter for speculative metaphysics… but

rather, a question for a materialist psychology. In any case, as to the

question of strength of character, it seems clear enough that “the idea of

pain is not the same thing as the suffering of it.” (47)

Let us agree then that there are different kinds of pain, distinguished

not only by their intensity and duration (which would be differences in

degree,) but also even by the nature of the process of recovery. Pleasure and

pain are not metric units by which we can measure suffering and desire;

rather, these ‘units’ refer only to a chance arrangement which (always and

already) dominates any process of becoming-healthy. To convalesce is not

only a postponement, merely an interruption of an already latent decay – but

the possibility of a truly new perspective, a closure of the continuum of

suffering which therefore unfolds every equivocation involved in the word

health.

Thus the question of the appropriate treatment is often social, not only

in its essential nature, but even in its eventual goal. Suffering deprograms,

and offers an opening towards a transvaluation – a window which opens itself

not before the master, but before the patient student of suffering. That we

are quite able to engage in a process of self-destruction just as easily as a

process of recovery is already the ambiguity of the cure. The sickness of a

thought is not its abnormality: rather it is just a different position with regard

to observation, not only of the beauty of health, but even of all the various

possibilities of experimentation. Medical experiments are almost universally

held to have an equal measure of science and cruelty, and this is no

accident. Insofar as the promise of science is merely an end to suffering, it is

a highly religious promise.

When Nietzsche writes that “it is in such men as are capable of that

suffering – how few they will be! – that the first attempt will be made to see

whether mankind could transform itself from a moral to a knowing mankind,”

(58) we believe that he is drawing a political distinction between the sickness

of religion and the cruelty of science. The question of health and sickness is

at once that of overcoming suffering as well as the broadest social question

of change, the possibility of a radical difference and overcoming. Thus in self-

overcoming we find a paradoxical interface between the two bodies (of God,

of the World) which is already a cataclysmic unfolding, a new way to become

healthy. We see in health a sort of eternal recurrence of the ever-different

question of social and biological adaptation, beyond the dominant

arrangement of forces.

You might also like

- Healers On HealingDocument5 pagesHealers On Healingmario100% (2)

- What Your Aches and Pains Are Telling You: Cries of the Body, Messages from the SoulFrom EverandWhat Your Aches and Pains Are Telling You: Cries of the Body, Messages from the SoulNo ratings yet

- Seven Secrets of Time Travel: Mystic Voyages of the Energy BodyFrom EverandSeven Secrets of Time Travel: Mystic Voyages of the Energy BodyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Business Demographic QuestionnaireDocument5 pagesBusiness Demographic QuestionnaireHemanth RatalaNo ratings yet

- MARKING SCHEME 1.3.1 Logic GatesDocument30 pagesMARKING SCHEME 1.3.1 Logic GateshassanNo ratings yet

- The Art of True Healing: The Unlimited Power of Prayer and VisualizationFrom EverandThe Art of True Healing: The Unlimited Power of Prayer and VisualizationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- Considerations of Disease by Dr. Edward Bach 1930Document18 pagesConsiderations of Disease by Dr. Edward Bach 1930Timing Magic with Lisa Allen MH100% (2)

- Corsini - Existential PsychotherapyDocument5 pagesCorsini - Existential Psychotherapynini345No ratings yet

- Peer Mediated Instruction ArticleDocument12 pagesPeer Mediated Instruction ArticleMaria Angela B. SorianoNo ratings yet

- On Suffering: Philosophical Reflections On What It Means To Be HumanDocument36 pagesOn Suffering: Philosophical Reflections On What It Means To Be Humangladbutterfly100% (3)

- The Metaphysics of TraumaDocument31 pagesThe Metaphysics of TraumaAngelica Maria Grande MontalvoNo ratings yet

- Unlocking Your Self-Healing Potential: A Journey Back to Health Through Authenticity, Self-determination and CreativityFrom EverandUnlocking Your Self-Healing Potential: A Journey Back to Health Through Authenticity, Self-determination and CreativityNo ratings yet

- (OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying Vol. 2 Iss. 4) Frankl, Viktor E. - Existential Escapism (1972) (10.2190 - JKVQ-YTQV-VLDV-3JKL) - Libgen - LiDocument5 pages(OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying Vol. 2 Iss. 4) Frankl, Viktor E. - Existential Escapism (1972) (10.2190 - JKVQ-YTQV-VLDV-3JKL) - Libgen - LiSwami KarunakaranandaNo ratings yet

- Book I The Nature of DiseaseDocument5 pagesBook I The Nature of DiseaseKhalid Latif KhanNo ratings yet

- Echoes of Sorrow: Navigating the Depths of a Heart Full of PainFrom EverandEchoes of Sorrow: Navigating the Depths of a Heart Full of PainNo ratings yet

- Nietzsche's Agon With Ressentiment: Towards A Therapeutic Reading of Critical TransvaluationDocument26 pagesNietzsche's Agon With Ressentiment: Towards A Therapeutic Reading of Critical TransvaluationfrankchouraquiNo ratings yet

- Pain As Negativity, Heidegger's Aesthetics & The Aesthetic Judgement of Pain by G. JensenDocument4 pagesPain As Negativity, Heidegger's Aesthetics & The Aesthetic Judgement of Pain by G. JensenGlenda JensenNo ratings yet

- Health and DiseaseDocument16 pagesHealth and DiseaseHaris LiviuNo ratings yet

- Existentialism and DisabilityDocument4 pagesExistentialism and DisabilityKellenRothNo ratings yet

- The Paradox of Healing PainDocument12 pagesThe Paradox of Healing PainWaseem RsNo ratings yet

- The Body Deva: Working with the Spiritual Consciousness of the BodyFrom EverandThe Body Deva: Working with the Spiritual Consciousness of the BodyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Wymbreck NietzscheDocument10 pagesWymbreck Nietzschebobjones1111No ratings yet

- The Philosophy Cure: Lessons on Living from the Great PhilosophersFrom EverandThe Philosophy Cure: Lessons on Living from the Great PhilosophersNo ratings yet

- Haydon Rochester The Gist of It 1919Document152 pagesHaydon Rochester The Gist of It 1919Vasco GuerreiroNo ratings yet

- Haydon Rochester - The Gist of It For Healing, Health and Happiness (1919)Document152 pagesHaydon Rochester - The Gist of It For Healing, Health and Happiness (1919)momir6856No ratings yet

- Rise Take Up Your Bed and Walk AttainingDocument40 pagesRise Take Up Your Bed and Walk Attaininggheorghealice0711No ratings yet

- The Myth of Psychotherapy: Mental Healing as Religion, Rhetoric, and RepressionFrom EverandThe Myth of Psychotherapy: Mental Healing as Religion, Rhetoric, and RepressionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

- Lo Normal y Lo Patologico. George CanguilhemDocument9 pagesLo Normal y Lo Patologico. George CanguilhemVirginiaNo ratings yet

- The Paradox of PainDocument2 pagesThe Paradox of Painashkatcham0381No ratings yet

- The Sacred Self - Introduction - Thomas CsordasDocument13 pagesThe Sacred Self - Introduction - Thomas CsordasAmy PenningtonNo ratings yet

- Eassy Humanities ContributeDocument9 pagesEassy Humanities Contributeoumou80No ratings yet

- PsychopathiaDocument26 pagesPsychopathiaKunal KejriwalNo ratings yet

- Conceptualizing Suffering and PainDocument11 pagesConceptualizing Suffering and PainHlatli Nia100% (1)

- Euthanasia Debate (Draft)Document4 pagesEuthanasia Debate (Draft)Evan Man TaglucopNo ratings yet

- First-Order and Second-Order SufferingDocument16 pagesFirst-Order and Second-Order Sufferingmarcelo DuarteNo ratings yet

- Ethics FinalsDocument22 pagesEthics FinalsEll VNo ratings yet

- 1986 Universal Aspects of Symbolic HealingDocument14 pages1986 Universal Aspects of Symbolic HealingLuana SouzaNo ratings yet

- Meaning of LifeDocument9 pagesMeaning of LifeMichael CameronNo ratings yet

- Speech 1NC 8-7 6PMDocument4 pagesSpeech 1NC 8-7 6PMEpic Chestnut100% (1)

- The History and Practice of Psychoanalysis (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandThe History and Practice of Psychoanalysis (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)No ratings yet

- EJOM Reinventing The Wheel Part IIDocument6 pagesEJOM Reinventing The Wheel Part IIlevimorchy2242No ratings yet

- Mental Healing and HypnosisDocument4 pagesMental Healing and HypnosisAmmienus MarcellinNo ratings yet

- On A Scale From 1 To 10: Life Writing and Lyrical PainDocument18 pagesOn A Scale From 1 To 10: Life Writing and Lyrical PainHS22D001 MalavikaNo ratings yet

- Inside Chronic Pain: An Intimate and Critical AccountFrom EverandInside Chronic Pain: An Intimate and Critical AccountRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Peace, Power & Plenty (Unabridged): Before a Man Can Lift Himself, He Must Lift His ThoughtFrom EverandPeace, Power & Plenty (Unabridged): Before a Man Can Lift Himself, He Must Lift His ThoughtNo ratings yet

- The HealerDocument30 pagesThe HealerRachel50% (2)

- Lesson 5Document80 pagesLesson 5Anthony Joseph ReyesNo ratings yet

- Why Energetic Therapies WorkDocument18 pagesWhy Energetic Therapies WorkSteve Evans100% (1)

- Chapter 20Document7 pagesChapter 20Mati GouskosNo ratings yet

- Nelkin 1994 - Reconsidering PainDocument20 pagesNelkin 1994 - Reconsidering PainLuis Enrique De La Mora RangelNo ratings yet

- With Joyful Acceptance, Maybe: Developing a Contemporary Theology of Suffering in Conversation with Five Christian Thinkers: Gregory the Great, Julian of Norwich, Jeremy Taylor, C. S. Lewis, and Ivone GebaraFrom EverandWith Joyful Acceptance, Maybe: Developing a Contemporary Theology of Suffering in Conversation with Five Christian Thinkers: Gregory the Great, Julian of Norwich, Jeremy Taylor, C. S. Lewis, and Ivone GebaraNo ratings yet

- Pastoral PsychologyDocument11 pagesPastoral PsychologynicajoseNo ratings yet

- The Case For Suffering Focused Ethics Lukas Gloor and Adriano ManninoDocument15 pagesThe Case For Suffering Focused Ethics Lukas Gloor and Adriano ManninoJaviera FargaNo ratings yet

- Hillman Suicide and The SoulDocument10 pagesHillman Suicide and The SoulRenzo Benvenuto100% (2)

- Csordas - The Sacred SelfDocument73 pagesCsordas - The Sacred SelfAmanda SerafimNo ratings yet

- HUMSS - DIASS12 - Module-5 - Gertrudes MalvarDocument16 pagesHUMSS - DIASS12 - Module-5 - Gertrudes MalvarAldrich SuarezNo ratings yet

- US3060165 Toxic RicinDocument3 pagesUS3060165 Toxic RicinJames LindonNo ratings yet

- Core Principles Behind The Agile ManifestoDocument2 pagesCore Principles Behind The Agile ManifestoAhmad Ibrahim Makki MarufNo ratings yet

- SM203 HSE Observations ChecklistDocument5 pagesSM203 HSE Observations ChecklistramodNo ratings yet

- Metal-Organic Frameworks and Their Postsynthetic ModificationDocument60 pagesMetal-Organic Frameworks and Their Postsynthetic ModificationDean HidayatNo ratings yet

- Literature Review in Research ProposalDocument5 pagesLiterature Review in Research Proposalmzgxwevkg100% (1)

- The Contribution of Cognitive Psychology To The STDocument18 pagesThe Contribution of Cognitive Psychology To The STAshutosh SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Iv TimersDocument48 pagesIv TimersanishthNo ratings yet

- Influence Without Authority PresentationDocument18 pagesInfluence Without Authority Presentationatroutt100% (1)

- Reconfiguring Area Studies For Global AgeDocument27 pagesReconfiguring Area Studies For Global AgePasquimelNo ratings yet

- BeedDocument2 pagesBeedCharuzu SanNo ratings yet

- Indian RailWay E Ticket ExampleDocument1 pageIndian RailWay E Ticket ExamplegouthamlalNo ratings yet

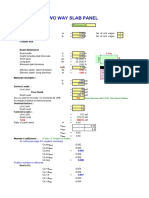

- Slab and Beam Design CalculationsDocument29 pagesSlab and Beam Design CalculationsAwais HameedNo ratings yet

- Full Download Introduction To Behavioral Research Methods 6th Edition Leary Solutions ManualDocument36 pagesFull Download Introduction To Behavioral Research Methods 6th Edition Leary Solutions Manualethanr07ken100% (26)

- XCELL48 v2Document8 pagesXCELL48 v2paulmarlonromme8809No ratings yet

- Module 3Document1 pageModule 3Shnx ArtNo ratings yet

- Sociotropy, Autonomy, and Self-CriticismDocument10 pagesSociotropy, Autonomy, and Self-Criticismowilm892973100% (1)

- Daf-Brochure LF PDFDocument28 pagesDaf-Brochure LF PDFIonut AnghelutaNo ratings yet

- Depth InterviewDocument23 pagesDepth InterviewRevs MenonNo ratings yet

- User Interface Evaluation Methods For Internet Banking Web Sites: A Review, Evaluation and Case StudyDocument6 pagesUser Interface Evaluation Methods For Internet Banking Web Sites: A Review, Evaluation and Case StudyPanayiotis ZaphirisNo ratings yet

- Steel Final Project: Prepared By: Siva Soran Supervised By: Mr. Shuaaib A. MohammedDocument25 pagesSteel Final Project: Prepared By: Siva Soran Supervised By: Mr. Shuaaib A. Mohammedsiva soranNo ratings yet

- DatabaseDocument326 pagesDatabaseFurukawa SaiNo ratings yet

- Pipe Drafting and DesignDocument38 pagesPipe Drafting and DesignMohammad TaherNo ratings yet

- Drilling Blowout PreventionDocument203 pagesDrilling Blowout PreventionLuisBlandón100% (1)

- Fairchild Display Power SolutionDocument58 pagesFairchild Display Power SolutionFrancisco Antonio100% (1)

- Gym Membership Application PDF Format DownloadDocument4 pagesGym Membership Application PDF Format DownloadFranco Evale YumulNo ratings yet

- 6 - MikroalgaDocument52 pages6 - MikroalgaSyohibhattul Islamiyah BaharNo ratings yet