Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chemistry For Chefs: Are Chem-Chefs Happier Than Chief Chemists?

Chemistry For Chefs: Are Chem-Chefs Happier Than Chief Chemists?

Uploaded by

Gary McCammonOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chemistry For Chefs: Are Chem-Chefs Happier Than Chief Chemists?

Chemistry For Chefs: Are Chem-Chefs Happier Than Chief Chemists?

Uploaded by

Gary McCammonCopyright:

Available Formats

Chemistry for Chefs

Are chem-chefs happier than chief chemists?

If I think about the chemistry of cooking while Im in the kitchen, it may distract me from eating my next monsterpiece before its actually served. In general it will--hopefully for my wifes sake---get me to spend more time at the stove and convert monsterpieces into masterpieces. The first set of common reactions that caught my fancy are of the Maillard type. With the addition of heat, the amino group (NH2) of amino acids attacks the carbonyl group (C=O) of a reducing sugar eventually leading to a range of brownish and appetizing compounds. Do you have to worry the notorious acrylamide produced at higher temperatures if you cook in a cool kitchen? Here are some examples of baking and cooking products that include compounds from Maillard reactions: 1) Bread crust 2) Boiling of maple syrup 3) Roasting of almonds, coffee or cocoa nuts 4) Beer-making (wheres the heat you may wonder? Its the heat of fermentation. 5) Cookie baking The first compound formed from the amino attack is an N-substituted glycosylamine.(see aldo pentose example in the diagram) But the hexagonal ring of this molecule then breaks up, undergoes another rearrangement with the help of a pH change to produce an Amadori compound.

What happens to this typ eof compound depends on pH, but in either case the NH2 group is lost forming ketones.(A compound with C=O group sandwiched between carbons.)

In the next stage, these compounds are split into some of the brown compounds that we taste and smell. Here are some examples

Maillard reactions occur alongside caramelization (bonding of sugars) that also leads to browning. While Maillard reactions are taking place, amino acids can decompose into Schiff bases that eventually produce cereal like flavours and those of roasted nuts, bread and meat. Unless a sweet sauce is added to meat, the browning seen upon cooking is not a Maillard reaction. Rather it results from the oxidation of the Fe+2 in myoglobin to the Fe+3 state. This is part of the reaction where the myoglobin protein is denatured to hemichrome. And when a cooked leaf loses its green colour, it is because chlorophyll has lost its Mg+2 ion. Like most reactions it depends on enzymes. In this case if you want to maintain the green colour, a little baking soda can be added. (not too much or youll gain both colour and bitterness) The higher pH from HCO3- prevents the enzyme from converting chlorophyll into pheophytin. If you are non-meat eater, you wont mind me switching the topic from meat to seafood. Astaxanthin is a compound related to the carotene in carrots. It is pink and found in shrimp.

C40H56 carotene

OH

O O

HO

astaxanthinC40H52O4

Normally while the shrimp is alive, the pink colour of astaxanthin is not evident because it is bound to a protein, which changes its colour. But the heat of cooking uncoils the protein, unsheathing the same pigment that keeps flamingos feathers pink. A similar explanation applies to the blue/green to red colour change for cooked lobsters. (And by the way they do not scream when boiled. Placing them directly in boiling water is indeed painful for them, but the sharp sound is from the steam that escapes from their shell.)

Notice how similar astaxanthin is to carotene. But the extra C=O group in astaxanthin increases the alternating single-double bond network, which makes it easier for electrons to get excited to higher energy levels. Compared to carotene, astaxanthin needs less energy or that of a longer wavelength for electronic excitation. This is consistent with the fact that astaxanthin reflects color of a longer wavelength: pink instead of orange. By the way, if you find a flamingo feather, keep it. Astaxanthin sells for $ 7000/kg! Of course a feather will have a negligible fraction of astaxanthin, so look for a lost flamingo instead. In both cooking and food packaging, there is often a basis behind seemingly arbitrary procedures. For example, in cartons, an egg is stored with its narrow point down. Why? The wider end contains the air pocket, which due to its lower density tends to rise away from the yolk when the egg is stored in this proper position. When the egg is inverted, the air pocket, which contains bacterial and fungal spores, will rise into the yolk and lower its shelf life. We often distort reality by trying to operate by simple rules of thumb. This certainly applies to vitamins in fruits and vegetables. Cooking certainly reduces the concentration of vitamins in food, but it does not destroy them, as shown in the table below: Effect of Heat on Vitamins Source; USDA Food(100g) carrots red peppers broccoli Vit A in Raw(IU) 28129 5700 3000 Vit A in Cooked(IU) 17202 2760 1967 Vit C in Raw(mg) 5.9 190 93 Vit C in Cooked(mg) 3.6 163 65

And where in the fruit and vegetable are the vitamins located? Does the peel contain a lot of nutrients? The answer varies. In the case of the potato, the peel does have fiber and minerals, and baking with the peel prevents the escape of some vitamin C during the cooking process. I have not been able to verify the claim that

most of the vitamin C is in the flesh just underneath the peel. In the case of mangos, vitamin A is distributed evenly throughout the orange pulp, which is coloured by similar beta carotene molecules. But the peel, especially when ripe, has antioxidants, carotenes and vitamin C. Apple peels are not devoid of nutrients either: they contain minerals (K+, Mg+2), antioxidants and fiber. Finally a great example of another endothermic reaction in the kitchen: cooking avocados. Some compounds in the avocado will be converted into bitter alkaloids with heat. But if the avocados are added towards the end of a recipe to minimize the amount of heat absorbed, then the amount of bitter-tasting products will be kept to a miniumum.

References

-Barham, Peter. Molecular Gastronomy. American Chemical Society 2010 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2855180/ -Atkins, P.W. Molecules. Scientific American Library. 1987 -McGee, Harold. On food and cooking: the science and lore of the kitchen. Simon & Schuster. 2004 -C.M. Ajilaa, S.G. Bhata and U.J.S. Prasada Rao. Valuable components of raw and ripe peels from two Indian mango varieties Central Food Technological Research Institute -United States Department of Agriculture usda.org -http://www.plantphysiol.org/cgi/reprint/39/6/1056.pdf

You might also like

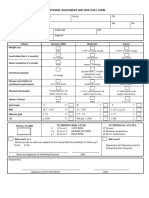

- 4 - Nutritional Assessment and Risk LevelDocument1 page4 - Nutritional Assessment and Risk LevelBok MatthewNo ratings yet

- UNIT 2 Heatlh and Safety in The Aviation Industry Lesson 1Document16 pagesUNIT 2 Heatlh and Safety in The Aviation Industry Lesson 1NekaNo ratings yet

- Advanced Level Craft RoastingDocument8 pagesAdvanced Level Craft RoastingStijn Braas75% (4)

- EXPERIMENT 5 Food Chemistry Egg White AlbuminDocument5 pagesEXPERIMENT 5 Food Chemistry Egg White AlbuminNurmazillazainal100% (3)

- Vitamin C in Food ProcessingDocument4 pagesVitamin C in Food ProcessingKishor Parihar100% (1)

- Biochemistry Homework HelpDocument10 pagesBiochemistry Homework HelpassignmentpediaNo ratings yet

- SYS-6010A Infusion Pump Operation Manual - V1.1Document66 pagesSYS-6010A Infusion Pump Operation Manual - V1.1bprz75% (4)

- Full Name DOB As in Your Checklist As in Your Checklist As in Your Checklist As in Your ChecklistDocument2 pagesFull Name DOB As in Your Checklist As in Your Checklist As in Your Checklist As in Your ChecklistSonam Pelden100% (1)

- Federal University of Agriculture, Makurdi College of Food Science and Technology Department of Food Science and TechnologyDocument13 pagesFederal University of Agriculture, Makurdi College of Food Science and Technology Department of Food Science and Technologyalyeabende moses msenNo ratings yet

- Pembentukan Senyawa Flavor Pada Reaksi MaillardDocument4 pagesPembentukan Senyawa Flavor Pada Reaksi MaillardUlul Ilmi ArhamNo ratings yet

- Roast MarApr08 ScienceofBrowningDocument5 pagesRoast MarApr08 ScienceofBrowningmadbakingNo ratings yet

- Fermentation: University of Diyala College of Engineering Department of Chemical EngineeringDocument13 pagesFermentation: University of Diyala College of Engineering Department of Chemical EngineeringEnegineer HusseinNo ratings yet

- Experiment 4 BIO121Document12 pagesExperiment 4 BIO121Pui Ling ChanNo ratings yet

- Browning Reactions in FoodsDocument19 pagesBrowning Reactions in FoodsImg UsmleNo ratings yet

- Alterations Occurring in Fruits and VegetablesDocument5 pagesAlterations Occurring in Fruits and VegetablesYU TANo ratings yet

- A4 Food Spoilage & PreservationDocument15 pagesA4 Food Spoilage & PreservationRavi kishore KuchiyaNo ratings yet

- Food Processing 1Document31 pagesFood Processing 1Casio Je-urNo ratings yet

- D02 Week 6Document21 pagesD02 Week 6Somi LeeNo ratings yet

- 15872242211HSCTC0201 Effects of Cooking On NutrientsDocument3 pages15872242211HSCTC0201 Effects of Cooking On NutrientsnablakNo ratings yet

- Science of FlavourDocument4 pagesScience of FlavourJosefBaldacchinoNo ratings yet

- Maillard ReactionDocument19 pagesMaillard Reactionapi-546795600No ratings yet

- Arteagagómezabrilgalilea IpqtraducciónDocument17 pagesArteagagómezabrilgalilea IpqtraducciónYumeko HamadaNo ratings yet

- Maillard ReactionDocument17 pagesMaillard ReactionjawwadNo ratings yet

- Exam FinalDocument11 pagesExam FinalsimurabiyeNo ratings yet

- Lecture 08 (Mass Food Production)Document6 pagesLecture 08 (Mass Food Production)Kaustubh MoreNo ratings yet

- Vitamin C in Food ProcessingDocument5 pagesVitamin C in Food ProcessingKishor PariharNo ratings yet

- Nutrient Losses Throughout The Blood FlowDocument2 pagesNutrient Losses Throughout The Blood FlowGwenethVineEscalanteNo ratings yet

- ProteinsDocument8 pagesProteinsNara100% (1)

- 1/ Reaction Involving Residues in Proteins: by Acidic AgentsDocument6 pages1/ Reaction Involving Residues in Proteins: by Acidic AgentsVạn LingNo ratings yet

- Mr. Omar Alajil (أ. ليجعلا رمع) M.Sc Food TechnologyDocument51 pagesMr. Omar Alajil (أ. ليجعلا رمع) M.Sc Food TechnologyCaryl Alvarado SilangNo ratings yet

- Cabbage As NutritionDocument5 pagesCabbage As NutritionJohn ApostleNo ratings yet

- Why Does Your Coffee Taste and Smell DeliciousDocument1 pageWhy Does Your Coffee Taste and Smell DeliciousleandroniedbalskiNo ratings yet

- Youre WelcomeDocument5 pagesYoure Welcomeatena mgNo ratings yet

- 09 Is Microwave Food Unhealty NL 02-04eDocument8 pages09 Is Microwave Food Unhealty NL 02-04ekamilazurNo ratings yet

- Aea Chem SPMS PDFDocument23 pagesAea Chem SPMS PDFDaniel ConwayNo ratings yet

- Methods of Preservation of MeatDocument30 pagesMethods of Preservation of MeatAmit MauryaNo ratings yet

- Que No 5 B) Influence of Water Activity On Food Spoilage Reations Ans - Water Activity & Microbial GrowthDocument11 pagesQue No 5 B) Influence of Water Activity On Food Spoilage Reations Ans - Water Activity & Microbial GrowthAmit Kr GodaraNo ratings yet

- Aim and Objective of Cooking FoodDocument20 pagesAim and Objective of Cooking FoodAneesh Ramachandran PillaiNo ratings yet

- This Is Your Health, This Is Your Health On Cooked FoodDocument7 pagesThis Is Your Health, This Is Your Health On Cooked FoodJonasSunshine100% (1)

- To Cook With Dry Heat, As in An Oven or Near Hot Coals.Document10 pagesTo Cook With Dry Heat, As in An Oven or Near Hot Coals.Mad LuNo ratings yet

- Foods: Biogenic Amines, Phenolic, and Aroma-Related Compounds of Unroasted and Roasted Cocoa Beans With DiDocument19 pagesFoods: Biogenic Amines, Phenolic, and Aroma-Related Compounds of Unroasted and Roasted Cocoa Beans With DiNhật Nguyễn SĩNo ratings yet

- Chem ReportDocument5 pagesChem ReportFrancisco Jayme GuiangNo ratings yet

- 10 Importance of ChemistryDocument5 pages10 Importance of ChemistryDante SallicopNo ratings yet

- Module I Principles of Shelf Life Chapter 2. Modes of Food Deterioration and Food LossesDocument7 pagesModule I Principles of Shelf Life Chapter 2. Modes of Food Deterioration and Food LossesCaca PrianganNo ratings yet

- 16 Micro Analysis-Canned FoodDocument8 pages16 Micro Analysis-Canned Foodalda khairinaNo ratings yet

- Reactions of Fats and Fatty AcidsDocument9 pagesReactions of Fats and Fatty AcidsMalikHamzaNo ratings yet

- Chemistry in Cooking-Molecular GastronomyDocument18 pagesChemistry in Cooking-Molecular GastronomyNirek SaravananNo ratings yet

- 6 - Toxicants Formed During ProcessingDocument45 pages6 - Toxicants Formed During Processingismailmannur100% (1)

- Effects of Processing and StorageDocument8 pagesEffects of Processing and StorageTami HurleyNo ratings yet

- MG in en PMDocument6 pagesMG in en PMrahulnavetNo ratings yet

- Experiment 5 Food ChemDocument4 pagesExperiment 5 Food ChemNur mazilla bt zainal100% (1)

- Proteins Are Essential Nutrients For TheDocument9 pagesProteins Are Essential Nutrients For TheapriantokaNo ratings yet

- Document 17Document13 pagesDocument 17Oneal PaembonanNo ratings yet

- Food BasicsDocument30 pagesFood BasicsRupini SinnanPandian100% (1)

- Experiment No 1 PostDocument9 pagesExperiment No 1 PostShaina TabjanNo ratings yet

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Fermentation and Aerobic RespirationDocument10 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of Fermentation and Aerobic RespirationIan Gabriel MayoNo ratings yet

- Denaturation of ProteinsDocument16 pagesDenaturation of ProteinsLineah Untalan100% (2)

- Lab Report Gen. Chem.Document6 pagesLab Report Gen. Chem.Francesca GenerNo ratings yet

- KrebDocument6 pagesKrebreservamaximaNo ratings yet

- SaltingDocument39 pagesSaltingivy bontrostroNo ratings yet

- Presentation Of: Department of PETROCHEMICAL EngineeringDocument63 pagesPresentation Of: Department of PETROCHEMICAL EngineeringSadhan PadhiNo ratings yet

- Powers ChartDocument3 pagesPowers ChartGary McCammonNo ratings yet

- Violation TicketsDocument32 pagesViolation TicketsGary McCammon100% (2)

- Traveler 1800Document10 pagesTraveler 1800Gary McCammon100% (3)

- Usan Stem ListDocument30 pagesUsan Stem ListGary McCammonNo ratings yet

- Random Equipstuff For Hol (Roll D100)Document5 pagesRandom Equipstuff For Hol (Roll D100)Gary McCammonNo ratings yet

- Dead Simple Fantasy RPGDocument1 pageDead Simple Fantasy RPGGary McCammonNo ratings yet

- Using and Abusing Adderall: What's The Big Deal? by Katie Anthony University of KentuckyDocument4 pagesUsing and Abusing Adderall: What's The Big Deal? by Katie Anthony University of KentuckyJia Hui JoanaNo ratings yet

- Skripsi Nisa Pengaruh Edukasi Perilaku Personal Hygiene RevisiDocument110 pagesSkripsi Nisa Pengaruh Edukasi Perilaku Personal Hygiene RevisiannisaNo ratings yet

- Ds 3175Document1 pageDs 3175Muhammad TauqeerNo ratings yet

- ROG-HSE-PLC-003, Access and Egress PolicyDocument1 pageROG-HSE-PLC-003, Access and Egress PolicyvladNo ratings yet

- Ejercicios de Permutacion EstadisticaDocument2 pagesEjercicios de Permutacion EstadisticaAndresDiazNo ratings yet

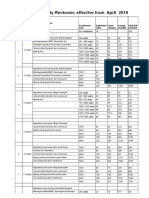

- Ready Reckoner of 2mmd Under New Tariff FY 19Document12 pagesReady Reckoner of 2mmd Under New Tariff FY 19podapodaNo ratings yet

- Bright Kids - 06092016Document12 pagesBright Kids - 06092016Times MediaNo ratings yet

- Magna Carta For Women - BrieferDocument15 pagesMagna Carta For Women - BrieferPaulo TapallaNo ratings yet

- Treachercollinssyndrome: Albaraa Aljerian,, Mirko S. GilardinoDocument9 pagesTreachercollinssyndrome: Albaraa Aljerian,, Mirko S. GilardinoSai KrupaNo ratings yet

- Mitral Regurgitation Etiology and Pathophysiology: Physical ExaminationsDocument11 pagesMitral Regurgitation Etiology and Pathophysiology: Physical ExaminationsDelmy SanjayaNo ratings yet

- Speech To Inform - Clara Angelina - 2021867406Document7 pagesSpeech To Inform - Clara Angelina - 2021867406clara anglnaNo ratings yet

- Stok BmjsDocument14 pagesStok BmjsAtik Marfu'ahNo ratings yet

- Tamaka GrahamDocument3 pagesTamaka GrahamTamaka GrahamNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Fetal WellbeingDocument177 pagesAssessment of Fetal Wellbeingvrutipatel100% (1)

- Specific Objective Teacher AND Learner Activity AV Aids: Time Content EvaluationDocument14 pagesSpecific Objective Teacher AND Learner Activity AV Aids: Time Content Evaluationthanuja mathewNo ratings yet

- A Paediatric Musculoskeletal Competence FrameworkDocument18 pagesA Paediatric Musculoskeletal Competence FrameworkPT Depart AMCHNo ratings yet

- Off-Season Football Training - Muscle & StrengthDocument12 pagesOff-Season Football Training - Muscle & StrengthTom HochhalterNo ratings yet

- Abdul Halim, Abu Sayeed Md. Abdullah, Fazlur Rahman, Animesh BiswasDocument11 pagesAbdul Halim, Abu Sayeed Md. Abdullah, Fazlur Rahman, Animesh BiswasNoraNo ratings yet

- 403ACIjournalsDocument10 pages403ACIjournalsNguyen Van QuyenNo ratings yet

- Secretary of Labor v. Barretto Granite Corporation, 830 F.2d 396, 1st Cir. (1987)Document8 pagesSecretary of Labor v. Barretto Granite Corporation, 830 F.2d 396, 1st Cir. (1987)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Hyoscine Hydrobromide PDFDocument3 pagesHyoscine Hydrobromide PDFNiluh Komang Putri PurnamantiNo ratings yet

- Facial Flow Final PDFDocument6 pagesFacial Flow Final PDFsamir caceresNo ratings yet

- NRNP PRAC 6635 Comprehensive Psychiatric Evaluation Template 2Document6 pagesNRNP PRAC 6635 Comprehensive Psychiatric Evaluation Template 2superbwriters10No ratings yet

- Chest Tube DrainageDocument3 pagesChest Tube DrainageCyndi Jane Bandin Cruzata100% (1)

- Utilities Pugeda Quiz 6Document1 pageUtilities Pugeda Quiz 6corazon philNo ratings yet