Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Global Games (Cambridge - 2003)

Global Games (Cambridge - 2003)

Uploaded by

chronoskatOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Global Games (Cambridge - 2003)

Global Games (Cambridge - 2003)

Uploaded by

chronoskatCopyright:

Available Formats

CHAPTER 3

Global Games: Theory and Applications

Stephen Morris and Hyun Song Shin

1. INTRODUCTION Many economic problems are naturally modeled as a game of incomplete information, where a players payoff depends on his own action, the actions of others, and some unknown economic fundamentals. For example, many accounts of currency attacks, bank runs, and liquidity crises give a central role to players uncertainty about other players actions. Because other players actions in such situations are motivated by their beliefs, the decision maker must take account of the beliefs held by other players. We know from the classic contribution of Harsanyi (19671968) that rational behavior in such environments not only depends on economic agents beliefs about economic fundamentals, but also depends on beliefs of higher-order i.e., players beliefs about other players beliefs, players beliefs about other players beliefs about other players beliefs, and so on. Indeed, Mertens and Zamir (1985) have shown how one can give a complete description of the type of a player in an incomplete information game in terms of a full hierarchy of beliefs at all levels. In principle, optimal strategic behavior should be analyzed in the space of all possible innite hierarchies of beliefs; however, such analysis is highly complex for players and analysts alike and is likely to prove intractable in general. It is therefore useful to identify strategic environments with incomplete information that are rich enough to capture the important role of higher-order beliefs in economic settings, but simple enough to allow tractable analysis. Global games, rst studied by Carlsson and van Damme (1993a), represent one such environment. Uncertain economic fundamentals are summarized by a state and each player observes a different signal of the state with a small amount of noise. Assuming that the noise technology is common knowledge among the players, each players signal generates beliefs about fundamentals, beliefs about other players beliefs about fundamentals, and so on. Our purpose in this paper is to describe how such models work, how global game reasoning can be applied to economic problems, and how this analysis relates to more general analysis of higher-order beliefs in strategic settings.

Global Games

57

One theme that emerges is that taking higher-order beliefs seriously does not require extremely sophisticated reasoning on the part of players. In Section 2, we present a benchmark result for binary action continuum player games with strategic complementarities where each player has the same payoff function. In a global games setting, there is a unique equilibrium where each player chooses the action that is a best response to a uniform belief over the proportion of his opponents choosing each action. Thus, when faced with some information concerning the underlying state of the world, the prescription for each player is to hypothesize that the proportion of other players who will opt for a particular action is a random variable that is uniformly distributed over the unit interval and choose the best action under these circumstances. We dub such beliefs (and the actions that they elicit) as being Laplacian, following Laplaces (1824) suggestion that one should apply a uniform prior to unknown events from the principle of insufcient reason. A striking feature of this conclusion is that it reconciles Harsanyis fully rational view of optimal behavior in incomplete information settings with the dissenting view of Kadane and Larkey (1982) and others that rational behavior in games should imply only that each player chooses an optimal action in the light of his subjective beliefs about others behavior, without deducing his subjective beliefs as part of the theory. If we let those subjective beliefs be the agnostic Laplacian prior, then there is no contradiction with Harsanyis view that players should deduce rational beliefs about others behavior in incomplete information settings. The importance of such analysis is not that we have an adequate account of the subtle reasoning undertaken by the players in the game; it clearly does not do justice to the reasoning inherent in the Harsanyi program. Rather, its importance lies in the fact that we have access to a form of short-cut, or heuristic device, that allows the economist to identify the actual outcomes in such games, and thereby open up the possibility of systematic analysis of economic questions that may otherwise appear to be intractable. One instance of this can be found in the debate concerning self-fullling beliefs and multiple equilibria. If one set of beliefs motivates actions that bring about the state of affairs envisaged in those beliefs, while another set of selffullling beliefs bring about quite different outcomes, then there is an apparent indeterminacy in the theory. In both cases, the beliefs are logically coherent, consistent with the known features of the economy, and are borne out by subsequent events. However, we do not have any guidance on which outcome will transpire without an account of how the initial beliefs are determined. We have argued elsewhere (Morris and Shin, 2000) that the apparent indeterminacy of beliefs in many models with multiple equilibria can be seen as the consequence of two modeling assumptions introduced to simplify the theory. First, the economic fundamentals are assumed to be common knowledge. Second, economic agents are assumed to be certain about others behavior in equilibrium. Both assumptions are made for the sake of tractability, but they do much more besides.

58

Morris and Shin

They allow agents actions and beliefs to be perfectly coordinated in a way that invites multiplicity of equilibria. In contrast, global games allow theorists to model information in a more realistic way, and thereby escape this straitjacket. More importantly, through the heuristic device of Laplacian actions, global games allow modelers to pin down which set of self-fullling beliefs will prevail in equilibrium. As well as any theoretical satisfaction at identifying a unique outcome in a game, there are more substantial issues at stake. Global games allow us to capture the idea that economic agents may be pushed into taking a particular action because of their belief that others are taking such actions. Thus, inefcient outcomes may be forced on the agents by the external circumstances even though they would all be better off if everyone refrained from such actions. Bank runs and nancial crises are prime examples of such cases. We can draw the important distinction between whether there can be inefcient equilibrium outcomes and whether there is a unique outcome in equilibrium. Global games, therefore, are of more than purely theoretical interest. They allow more enlightened debate on substantial economic questions. In Section 2.3, we discuss applications that model economic problems using global games. Global games open up other interesting avenues of investigation. One of them is the importance of public information in contexts where there is an element of coordination between the players. There is plentiful anecdotal evidence from a variety of contexts that public information has an apparently disproportionate impact relative to private information. Financial markets apparently overreact to announcements from central bankers that merely state the obvious, or reafrm widely known policy stances. But a closer look at this phenomenon with the benet of the insights given by global games makes such instances less mysterious. If market participants are concerned about the reaction of other participants to the news, the public nature of the news conveys more information than simply the face value of the announcement. It conveys important strategic information on the likely beliefs of other market participants. In this case, the overreaction would be entirely rational and determined by the type of equilibrium logic inherent in a game of incomplete information. In Section 3, these issues are developed more systematically. Global games can be seen as a particular instance of equilibrium selection though perturbations. The set of perturbations is especially rich because it turns out that they allow for a rich structure of higher-order beliefs. In Section 4, we delve somewhat deeper into the properties of general global games not merely those whose action sets are binary. We discuss how global games are related to other notions of equilibrium renements and what is the nature of the perturbation implicit in global games. The general framework allows us to disentangle two properties of global games. The rst property is that a unique outcome is selected in the game. A second, more subtle, question is how such a unique outcome depends on the underlying information structure and the noise in the players signals. Although in some cases the outcome is sensitive to the details of the information structure, there are cases where a particular outcome

You might also like

- Chapter 3: Game Theory: Game Theory Extends The Theory of Individual Decision-Making ToDocument20 pagesChapter 3: Game Theory: Game Theory Extends The Theory of Individual Decision-Making Toshipra100% (2)

- Working Paper Series BDocument7 pagesWorking Paper Series BGigih PringgondaniNo ratings yet

- Organization ComDocument40 pagesOrganization ComLisan AhmedNo ratings yet

- Game Theory: Sri Sharada Institute of Indian Management - ResearchDocument20 pagesGame Theory: Sri Sharada Institute of Indian Management - ResearchPrakhar_87No ratings yet

- Game Theory: A Guide to Game Theory, Strategy, Economics, and Success!From EverandGame Theory: A Guide to Game Theory, Strategy, Economics, and Success!No ratings yet

- BPSM7103 Advanced Strategic Management Assignment Jan 2020Document45 pagesBPSM7103 Advanced Strategic Management Assignment Jan 2020J PHUAHNo ratings yet

- What Is Game TheoryDocument10 pagesWhat Is Game TheoryAbbas Jan Bangash0% (1)

- Research Paper Topic - Game Theory: Table of ContactsDocument9 pagesResearch Paper Topic - Game Theory: Table of ContactsPriyanshi SoniNo ratings yet

- Iterative Dominance in Game TheoryDocument19 pagesIterative Dominance in Game TheorySundaramali Govindaswamy GNo ratings yet

- What Is Game TheoryDocument4 pagesWhat Is Game TheoryssafihiNo ratings yet

- 002 Thakor 1991 Survey Game Theory and FinancesDocument14 pages002 Thakor 1991 Survey Game Theory and FinancesIdeas Guarani KaiowaNo ratings yet

- Pareja, Nelvie Mae C. - Assignment No. 3Document8 pagesPareja, Nelvie Mae C. - Assignment No. 3Nelvie Mae ParejaNo ratings yet

- Game TheoryDocument7 pagesGame TheorysithcheyNo ratings yet

- Game TheoryDocument21 pagesGame TheoryJoan Albet SerraNo ratings yet

- Game TheoryDocument8 pagesGame TheoryZaharatul Munir SarahNo ratings yet

- Iterative Dominance in Game Theory-IDocument19 pagesIterative Dominance in Game Theory-ISundaramali Govindaswamy GNo ratings yet

- Economics and Balance - EditedDocument4 pagesEconomics and Balance - EditedMlangeni SakhumuziNo ratings yet

- Spill Learn Path 8Document42 pagesSpill Learn Path 8f1sky4242No ratings yet

- A Study On Game TheoryDocument7 pagesA Study On Game TheoryJanmar OlanNo ratings yet

- Trust vs. Macroeconomic and Political Stability, An Experimental ApproachDocument7 pagesTrust vs. Macroeconomic and Political Stability, An Experimental ApproachSamar EissaNo ratings yet

- How To Identify Trust and Reciprocity: James C. CoxDocument22 pagesHow To Identify Trust and Reciprocity: James C. CoxMario Alexander Diaz CaraballoNo ratings yet

- Report SkillDocument14 pagesReport Skillsunil hansdaNo ratings yet

- Complexity in Economic and Financial MarketsDocument16 pagesComplexity in Economic and Financial Marketsdavebell30No ratings yet

- Asset Pricing and Sports BettingDocument76 pagesAsset Pricing and Sports BettingNeal Erickson100% (1)

- Sonnemann Camerer Fox Langer 2013 - Behavioral FinanceDocument6 pagesSonnemann Camerer Fox Langer 2013 - Behavioral FinancevalleNo ratings yet

- Aoki Endogenizing InstitutionsDocument39 pagesAoki Endogenizing InstitutionsecrcauNo ratings yet

- Method For Numerical Investigation Game TheoryDocument3 pagesMethod For Numerical Investigation Game Theoryyorany físicoNo ratings yet

- Game Theory & Nash EquilibriumDocument3 pagesGame Theory & Nash EquilibriumdamarismagererNo ratings yet

- Dufwenberg 2004Document31 pagesDufwenberg 2004SNamNo ratings yet

- Game TheoryDocument26 pagesGame Theorynoelia gNo ratings yet

- Game TheoryDocument3 pagesGame Theorywake up PhilippinesNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Conflict A111Document35 pagesAn Analysis of Conflict A111accelwNo ratings yet

- Cultures of Kindness - A Meta Analysis of Trust Game Experiments PDFDocument58 pagesCultures of Kindness - A Meta Analysis of Trust Game Experiments PDFfarnaz_2647334No ratings yet

- Game Theory Project Oct '08Document16 pagesGame Theory Project Oct '08Ruhi SonalNo ratings yet

- What Is Game Theory?Document5 pagesWhat Is Game Theory?Akriti SinghNo ratings yet

- Game Theory Thesis IdeasDocument8 pagesGame Theory Thesis IdeasPaySomeoneToWriteYourPaperSpringfield100% (2)

- Complexity Financial MarketsDocument16 pagesComplexity Financial MarketsmanuelbrionesNo ratings yet

- Learning and Evolutionary Game TheoryDocument7 pagesLearning and Evolutionary Game TheorygvpapasNo ratings yet

- Game Theory ModelsDocument64 pagesGame Theory ModelsAngelo PolimenoNo ratings yet

- Australian Journal of Agricultural Economics - June 1969 - Longworth - MANAGEMENT GAMES AND THE TEACHING OF FARM MANAGEMENTDocument10 pagesAustralian Journal of Agricultural Economics - June 1969 - Longworth - MANAGEMENT GAMES AND THE TEACHING OF FARM MANAGEMENTlourdusamy0006No ratings yet

- Artigo - But Who Will Guard The Guardians (Leonid Hurwicz)Document12 pagesArtigo - But Who Will Guard The Guardians (Leonid Hurwicz)Rafael VasconcellosNo ratings yet

- Intelligence, Personality, and Gains From Cooperation in Repeated InteractionsDocument40 pagesIntelligence, Personality, and Gains From Cooperation in Repeated InteractionsLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- Paper 04 Rubinstein (1991)Document17 pagesPaper 04 Rubinstein (1991)jacoboNo ratings yet

- Jervis Preception MispreceptionDocument15 pagesJervis Preception MispreceptionLolo SilvanaNo ratings yet

- A Review On Game Theory As A Tool in Operation ResearchDocument22 pagesA Review On Game Theory As A Tool in Operation ResearchRaphael OnuohaNo ratings yet

- 2144051-Sarah Aryana-UTS Games TheoryDocument26 pages2144051-Sarah Aryana-UTS Games TheorySarah AryanaNo ratings yet

- Order #860801Document7 pagesOrder #860801Reece JMNo ratings yet

- Game TheoryDocument10 pagesGame TheoryKiran Patil100% (1)

- EconomicsDocument7 pagesEconomicsshiwani chaudharyNo ratings yet

- Game TheoryDocument3 pagesGame TheoryShaheryar RashidNo ratings yet

- Note On Basic GT ConceptsDocument5 pagesNote On Basic GT ConceptsmatthewvanherzeeleNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Hierarchy TheoryDocument18 pagesCognitive Hierarchy TheoryLucianoNo ratings yet

- Proto Rustichini Sofianos (2018) Intelligence PT RGDocument149 pagesProto Rustichini Sofianos (2018) Intelligence PT RGLeonardo SimonciniNo ratings yet

- The Game TheoryDocument10 pagesThe Game TheoryZedek PeterNo ratings yet

- Coor1 PDFDocument17 pagesCoor1 PDFblue 1234No ratings yet

- Faingold SannikovDocument84 pagesFaingold SannikovAnonymous y0GMKcadZBNo ratings yet

- Rock Lick 25 PDFDocument1 pageRock Lick 25 PDFchronoskatNo ratings yet

- Forward Roll Patterns With Chords D, G, and A: Pattern 19Document1 pageForward Roll Patterns With Chords D, G, and A: Pattern 19chronoskatNo ratings yet

- 36 Rock SauceDocument1 page36 Rock SaucechronoskatNo ratings yet

- Jazz Up Your BluesDocument1 pageJazz Up Your BlueschronoskatNo ratings yet

- Gettin' Comfortable: Angus ClarkDocument1 pageGettin' Comfortable: Angus ClarkchronoskatNo ratings yet

- Jump Start Fingerstyle 2Document1 pageJump Start Fingerstyle 2chronoskatNo ratings yet

- Jazz Rock 03Document1 pageJazz Rock 03chronoskatNo ratings yet

- Jump Start Fingerstyle 1Document1 pageJump Start Fingerstyle 1chronoskatNo ratings yet

- Down & Dirty: Angus ClarkDocument1 pageDown & Dirty: Angus ClarkchronoskatNo ratings yet

- Sliding Ascent Minor: Angus ClarkDocument1 pageSliding Ascent Minor: Angus ClarkchronoskatNo ratings yet

- Best V Chord Lick Ever: Angus ClarkDocument1 pageBest V Chord Lick Ever: Angus ClarkchronoskatNo ratings yet

- Double Stop Sixths: Angus ClarkDocument1 pageDouble Stop Sixths: Angus ClarkchronoskatNo ratings yet

- Radio Rock Lick 16Document1 pageRadio Rock Lick 16chronoskatNo ratings yet

- Bending Major Descent: Angus ClarkDocument1 pageBending Major Descent: Angus ClarkchronoskatNo ratings yet

- Radio Rock Lick 12Document1 pageRadio Rock Lick 12chronoskatNo ratings yet

- Radio Rock Lick 9Document1 pageRadio Rock Lick 9chronoskatNo ratings yet

- Comin' On Strong: Angus ClarkDocument1 pageComin' On Strong: Angus ClarkchronoskatNo ratings yet

- Radio Rock Lick 4Document1 pageRadio Rock Lick 4chronoskatNo ratings yet

- Radio Rock Lick 10Document1 pageRadio Rock Lick 10chronoskatNo ratings yet

- Stutter Descend Bend: Angus ClarkDocument1 pageStutter Descend Bend: Angus ClarkchronoskatNo ratings yet

- Radio Rock Lick 1Document1 pageRadio Rock Lick 1chronoskatNo ratings yet

- Bending Major Ascent: Angus ClarkDocument1 pageBending Major Ascent: Angus ClarkchronoskatNo ratings yet

- Descending Sixes: Angus ClarkDocument1 pageDescending Sixes: Angus ClarkchronoskatNo ratings yet

- Bop Slide Minor: Angus ClarkDocument1 pageBop Slide Minor: Angus ClarkchronoskatNo ratings yet

- King of The BeesDocument2 pagesKing of The BeeschronoskatNo ratings yet

- Canon Rock (Violin)Document2 pagesCanon Rock (Violin)chronoskatNo ratings yet

- Stochastic Volatility and Local VolatilityDocument1 pageStochastic Volatility and Local VolatilitychronoskatNo ratings yet

- Young Kings (T.me-Riset9)Document25 pagesYoung Kings (T.me-Riset9)PRASOON PATELNo ratings yet

- EBS 2 Module Student Version Updated 10022020Document18 pagesEBS 2 Module Student Version Updated 10022020mark lester panganibanNo ratings yet

- EpicorDocument15 pagesEpicorsalesh100% (1)

- Applications Are Invited in Prescribed Format Available Online On Shivaji University WebsiteDocument3 pagesApplications Are Invited in Prescribed Format Available Online On Shivaji University WebsiteAtul TcsNo ratings yet

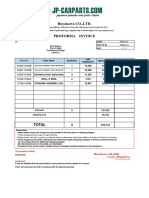

- Hayakawa CO.,LTD.: TO: Dated: 08/01/19 Invoice No.: 190801421 1 / 1Document1 pageHayakawa CO.,LTD.: TO: Dated: 08/01/19 Invoice No.: 190801421 1 / 1Earl CharlesNo ratings yet

- Chaudhary Charan Singh University, Meerut: Bachelor of Business Administration (B.B.A.)Document49 pagesChaudhary Charan Singh University, Meerut: Bachelor of Business Administration (B.B.A.)Pari SharmaNo ratings yet

- Capitalization Rules: Unless It Appears at The Beginning of A SentenceDocument3 pagesCapitalization Rules: Unless It Appears at The Beginning of A SentenceHanah Abegail NavaltaNo ratings yet

- CLJ 1 - PCJSDocument41 pagesCLJ 1 - PCJSSay DoradoNo ratings yet

- Essays On Contemporary Issues in AfricanDocument19 pagesEssays On Contemporary Issues in AfricanDickson Omukuba JuniorNo ratings yet

- GST - E-InvoicingDocument17 pagesGST - E-Invoicingnehal ajgaonkarNo ratings yet

- Church of EnglandDocument34 pagesChurch of Englandbrian2chrisNo ratings yet

- G3X GarminDocument450 pagesG3X GarmincrguanapolloNo ratings yet

- NTJD CURRICULUM CHECKLIST SHIFTEES 115, 116, 117, 118 VSN 3 0Document41 pagesNTJD CURRICULUM CHECKLIST SHIFTEES 115, 116, 117, 118 VSN 3 0Jappy AlonNo ratings yet

- IBM Public Cloud Platform - Amigo2021Document24 pagesIBM Public Cloud Platform - Amigo2021Thai PhamNo ratings yet

- Unit 5a - VocabularyDocument1 pageUnit 5a - VocabularyCarlos ManriqueNo ratings yet

- 74-Article Text-292-1-10-20210928Document20 pages74-Article Text-292-1-10-20210928Dinda PardapNo ratings yet

- Moeller Consumer Units and The 17 Edition Wiring RegulationsDocument12 pagesMoeller Consumer Units and The 17 Edition Wiring RegulationsArvensisdesignNo ratings yet

- 1 5407Document37 pages1 5407Norman ScheelNo ratings yet

- Gilgit-Baltistan: Administrative TerritoryDocument12 pagesGilgit-Baltistan: Administrative TerritoryRizwan689No ratings yet

- Audit ChecklistDocument6 pagesAudit ChecklistSangeeta BSRNo ratings yet

- 12 Phrases That Will Defuse Any ArgumentDocument4 pages12 Phrases That Will Defuse Any ArgumentSidajayNo ratings yet

- Renewable Energy Mir 20200330 Web PDFDocument31 pagesRenewable Energy Mir 20200330 Web PDFJuan Carlos CastroNo ratings yet

- Book ReviewDocument4 pagesBook Reviewananya sinhaNo ratings yet

- Einstein God Does Not Play Dice SecDocument11 pagesEinstein God Does Not Play Dice SecyatusacomosaNo ratings yet

- Decoding A Term SheetDocument1 pageDecoding A Term Sheetsantosh kumar pandaNo ratings yet

- Silas Engineering Company ProfileDocument6 pagesSilas Engineering Company Profilesandesh negiNo ratings yet

- God Sees The Truth But WaitsDocument2 pagesGod Sees The Truth But WaitsrowenaNo ratings yet

- Edtpa Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesEdtpa Lesson Planapi-280516383No ratings yet

- The Gimmick of Health Insurance SchemesDocument42 pagesThe Gimmick of Health Insurance SchemesParag MoreNo ratings yet

- Company Information: 32nd Street Corner 7th Avenue, Bonifacio Global City @globemybusiness Taguig, PhilippinesDocument3 pagesCompany Information: 32nd Street Corner 7th Avenue, Bonifacio Global City @globemybusiness Taguig, PhilippinesTequila Mhae LopezNo ratings yet