Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Teaching Students To Learn, Understand and Use Knowledge.

Teaching Students To Learn, Understand and Use Knowledge.

Uploaded by

Dr Malcolm SutherlandOriginal Title

Copyright

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Teaching Students To Learn, Understand and Use Knowledge.

Teaching Students To Learn, Understand and Use Knowledge.

Uploaded by

Dr Malcolm SutherlandCopyright:

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

TEACHING STUDENTS TO REMEMBER, UNDERSTAND AND USE KNOWLEDGE

A radical proposal for teaching students in a way which coerces them into memorising information, gathering data, solving problems and preparing themselves for the job interview room and the professional workplace

Written by Dr Malcolm Sutherland (LabSearch Ltd co-director)

MARCH 2013

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

CONTENTS

Executive summary Personal background A brief comment on university structure and management The drawbacks with some common teaching methods today Some proposals Some more ambitious proposals In conclusion

2 3 3 4 8 16 19

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

This document examines some of the problems with current teaching methods used in Scottish universities (namely in UWS), and contains some proposals on new and better teaching methods, as well as on preparing students for the workplace. Some of the problems with teaching in Scottish universities include: lectures and labs being cancelled or rescheduled, and lecturers ignoring students; very long lecture slots and an overdependence on reading off powerpoint slides; weak assessment methods such as clicker class tests; no tutorial sessions in some modules, and students not being probed and regularly tested on how much they have learned; very long exams, and generous time limits for written coursework; a lack of practical work (laboratory and field work) or its absence (with online courses); a bureaucratic obsession with modules, and pass-rate targets; and, lecturers no longer publishing work in books, and large journal publishers controlling access to information.

Proposals to improve teaching quality and university standards include: restoring entrance exams, and small class sizes; making students attend five days a week; delivery of lectorials, whereby the lecturer sits with a small group of students and asks them questions on what they have learned, and issues a shopping list of topics and information the students must investigate for the next session; more laboratory and practical work, and allowing senior students to supervise lab sessions for junior students; making students deliver presentations on their reports and essays, and defend their findings before a examining panel; replacing the 1st, 2:1, 2:2 and 3rd class grades with a simple Pass or Fail; trying to make students think of answers without using technology, e.g. make them understand equations, or perform basic arithmetic, etc. so that they understand what they are doing; and, find ways to keep students busy all year around, e.g. set up contracts and use the labs during the summer months, whereby clients send in samples, and students can process them when there are no classes.

The prime aim of any education course is to motivate a pupil or student to focus, to read and write down information, and to memorise and understand it completely, before and during practical work. Once a student has mastered the ability to concentrate, read, collate, comprehend and remember information, then (s)he can start to think outside the box, and begin to apply logical thinking, gather further information and deduce solutions to problems.

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

PERSONAL BACKGROUND

I am writing this document, after having spent over 15 years working and studying at six universities. I started out as a catering assistant at the University of St Andrews in 1997, and worked at the same institution as a security porter a few years later; on both occasions I observed (and overheard conversations concerning) several social and financial tensions, which were detrimental to some of the students studies. I spent four years reading for a BSc (Hons) degree at the University of Glasgow, where I worked hard, and yet forgot most of what I had revised for the exams. I then spent a few months attending MSc classes at The University of Abertay Dundee, where MS PowerpointTM slides and 3-hour lecture slots had become protocol. I then spent another five years completing a dubious PhD project involving poorly calibrated equipment, which was led by a strange group of semi-industry academics who did not want me to publish papers. Near the end of my PhD project, I spent seven months at Loughborough University, in a publish-or-die post-doc position, and suffered a nervous breakdown. During the past three and a half years, I have tried hard to make a living as a note-taker at UWS Paisley, where I tried to work with colleagues to try and run various projects, all of which were either derailed or didnt take off, owing more than anything else to an endemic apathy and lack of vision among a majority of colleagues and students. I have spent much of my adult life communicating with students and academics, including my father who has devoted over 25 years to working as a computing lecturer. I have made friends with several students and lecturers over the years, as well as a few adversaries along the way. Although I possess neither an enviable publication record nor a chair of faculty nor a professorship, I believe that I can write this document in an authoritative tone, and that I have enough experience of university teaching to understand why a radical upheaval in teaching style is essential.

A BRIEF COMMENT ON UNIVERSITY STRUCTURE AND MANAGEMENT

I was brought up to believe that a university is an exclusive organisation serving the intellectual elite. I am unrepentant in my view that a university is for the enlightenment and training of smart people, to fashion them into professionals who can take this country forward. It is not for everyone. Tutors should be senior, highly experienced professionals with a track record of accomplishments both inside and outside the ivory tower. If every student is stupid, then every student must fail. Neither money nor abstract targets should compromise the difficulty and quality of courses. Research should be a means to an end: it must address problems affecting the real world, and contribute to the teaching material, in order to prepare students for the workplace and to assist the country.

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

I believe that a university should pay for itself. Every academic every researcher and lecturer must pay his or her own way, either through raising fees, or securing grants. Nobody should profit from the university. No state money or interference should infect its function. Libraries, and laboratory facilities and equipment should be funded through the necessary mark-up on fees or research funds. They should be further be used for outsourcing work, whereby clients send in requests or samples, upon which staff and students can work. The library should be accessible to the general public, and there should be seminars to which everyone both within and outside the university is invited. Students and scholars alike should share in communal chores and even with marketing the institution. Students and academics should run the library, manage computer systems and maintain equipment. The principalship should be a rotating portfolio held by one of the professors, and passed onto another professor after one year. Nobody else, save students and academics, should be wandering around on campus. Provided an academic can justify the needs of his/her work, and can attract enough students and pay for his/her own keep, (s)he should be answerable to no-one. No bureaucrats should control what documents (s)he uses, where (s)he teaches, how (s)he teaches (within reason), how (s)he sets out assessments, and how and when (s)he issues exam/test marks and ranks a students progress.

THE DRAWBACKS WITH SOME COMMON TEACHING METHODS TODAY

I am writing this document, because (i) I fear that many of the Scottish universities which exist today face a growing threat from various economic and technological forces, which are billowing in the midst of the current recession; and (ii) because I believe that the current teaching and assessment methods (especially in UWS where I work) are failing students, and reaping a harvest of unemployable graduates who are disadvantaged in their search for work. During my three and a half years of service to UWS, I have been privy to a staggering lack of enthusiasm, intelligence and dedication, exhibited by hundreds of staff and students. Teaching which for many students was once a five-day-a-week race track of classes and labs which ran for nearly 40 weeks a year has been reduced to two or three classes a week for 25 weeks a year. There was a time when student life revolved largely around studies. Nowadays, studies more often than not revolve around the more vestigial trials of life. Several students skip class and try to hand in late coursework assignments because of domestic issues and having to juggle part-time jobs. Lectures used to last one hour, and were once more frequent. Around 30 years ago, students were expected to show up on time at a class and collect their attendance tickets and complete all the necessary attendances at lectures, tutorials and lab sessions. I remember when lecturers would lock the doors at five past the hour (this was around 12 years ago). Nowadays, many students are perplexed when questioned why they turned up 20 minutes late or worse. Todays registritis epidemic of lecturers barking at students to sign attendance sheets also seems to lack a certain moral dimension.

4

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

Around the mid-20th century, most information was printed, handwritten, sketched into diagrams and had to be memorised. If you failed a test, it was your fault. The professor was supreme, and the lecturer was his own boss. Secretaries, clerks and auxiliary staff were very few in number. The principal had a quaint apartment and a modest stipend. Until the 1970s there were only a handful of universities, and less than 5% of school-leavers ever saw one. Students were the reason for the existence and activity of these once unique institutions. These days are a distant memory. Here are some of the deficiencies in the quality of teaching which I have witnessed (or which were reported) in recent years: Teaching is not a priority. It is not uncommon for many students to attend the campus only two days a week. Scandals erupted in some English universities last decade, where some arts students were only receiving a few hours of lectures and tutorials per week. I have witnessed lectures being cancelled or rescheduled at the last moment, and labs being annulled for administrative convenience. Stories abound of absent lecturers who are never in their offices, who cancel classes or even remove assessments from modules. I have been privy to some even worse practices, including lecturers not answering any queries from their students, and not even issuing test/exam marks. I have even heard some lecturers unashamedly state that they are focussed on their research and would rather not be teaching. The two to four-hour solid lecture slots. A one hour lecture can be tedious; three hours (even with short breaks) is simply counterproductive. I was also brought up in the church, and I know from years of enduring lectures and sermons that the brain can only absorb a slurry of information for about 30 to 40 minutes before short-circuiting. The marathon lecture slots crept into university timetables around a decade ago, and they benefit neither the lecturer nor the students. After two hours, everyone is fed up and wants to go home. Powerpoint slides. It is difficult to convey politely why powerpoint slide lectures are a nuisance. Here are my own reasons: o I believe they are a weak substitute for someone explaining something and spelling out his thoughts on the black/white-board. o Flagging up four bullet-points on a giant screen or pinching a diagram from Google images just looks tacky and unimaginative. Drawing a diagram and carefully annotating it is a necessary means for students to find out whether or not they understand what is being said. o I simply cannot tolerate the sight of several static powerpoint slides, with someone reading through them, and with nothing for me to write. As soon as the session begins, I feel as if my body is being drained of energy. My eyelids droop, my arms sag, my concentration dwindles and my ears draw the curtains. I am certain many students would concur...

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

o ...as they whip out their mobiles and send missives through social networks. o I think its a waste of time. Why not just email the powerpoint files to the students, and let them read these slides in their own time? Why do they need to attend this strange sort of public meeting? I feel it was more appropriate in the old days when information was contained in a few books, and the lecturer unfolded his secret knowledge to the students, guiding them on a mapped-out journey from first principles to complex solutions, through the use of chalk and a long stick, whilst the students copied the information onto notepad. Mass clicker and multiple choice class tests. Oh how I would love the interviewer in a job interview room to ask me a question, and present me with four possible answers, three of which are really silly! Multiple choice examinations almost defeat the purpose of an exam. If you cannot recall the correct answer, or are incapable of producing one, you deserve to fail. Two months after commencing my BSc course at Glasgow, I sat a class test for which I had conducted no revision. I randomly ticked the boxes, and scored 70%. Clicker class tests are similar, MS PowerpointTM-based, and even more absurd. The lecturer asks the class a question from the slide, and the students click A, B, C etc on little digital clicking devices, and the class results are produced on the screen. The intensity of being forced to recall what one has read and understood is almost absent from this exercise. No entrance exams, weak entrance requirements. There was a time when people had to pass an entrance examination in order to matriculate into a university. This was abolished many years ago, although my father sat his Highers in the mid-1970s, which were designated as university entrance exams. Even today, many university course leaders may issue conditional offers to prospective students, in that they must attain a certain number of grades A, B or C in order to meet the entrance requirements. I have witnessed several cases of school and college dropouts who failed exams and were still accepted onto university and FE college courses. Contrast this with Oxford or Cambridge, where you must have scored four to six As at school, and must pass entrance exams and attend interviews. I feel that those components should be restored. I am sorry to write this, but I have encountered far too many students who should have simply left school and taken a straight job. Coursework. I do accept that students should demonstrate a proficiency in writing reports, essays and commentaries on relevant issues and laboratory results. However, I am uncomfortable with the typical coursework assignment, whereby students are given several weeks or months to gather some data (some of which is given to them), and turn their findings into a 1500 word analysis and summary. In what way does this casual, slow exercise demonstrate true mastery and a problem-solving mindset? By contrast, a GP has to make decisions within minutes or hours. An engineer or lab technician has to think fast, and cannot always rely on books.

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

The long (two to three hour) written exam with short and long essay questions. Once again, I must express my misgivings on this style of assessment. I do accept that once a student has entered the examination hall, all books and notes are put away, and (s)he is all alone with only a brain, a pen, some paper and a limited amount of time to answer the questions without recourse. The problem is the length of time permitted. I spent many a long exam on my BSc and MSc courses mulling over the questions and scribbling short notes and organising my thoughts. I feel that this is not adequate preparation for the job interview room or the workplace. Taking the example of a GPs surgery, a patient doesnt provide a medical history, only to be told to give the GP two hours to think about it. A senior manager or scientist might have time to mull over a problem, but this is not always guaranteed. Information in the head should be sitting there, ready to be dispensed. Just imagine if a barrister is tongue-tied during a court session, and asks the judge if he could have two hours to run outside and think of an answer. The module system. Just as with powerpoint slides, I simply do not approve of modules. What exactly is a module? I do not deny that within a general discipline, e.g. Computing, there are various sub-disciplines, e.g. C++ programming. I am not against failing students who are good at some subjects, and completely incompetent in some others. However, modules have become an administrative obsession, and module points and credits have become false currencies. Employers could not care less. Is the applicant competent and knowledgeable, or not? The answer of I accumulated 220 UKAS points and passed six modules last session has mo re in common with the price of fish. I do believe that if a student is struggling at a certain stage in a course and is lacking the ability to process more advanced information, then (s)he needs to be dismissed from the course. No tutorials. In my judgement, tutorials are an essential icing on the cake of further education. The lecturer gathers half a dozen students from the class in a room, and probes them intensely on what they have learned and understood. This, in my opinion, is one reason why Oxford and Cambridge are considered to be excellent institutions. Sitting in a class of 100 people for a lecture is less inspiring; being closely probed and criticised and tested by a lecturer for an hour will command more revision and effort from a lot of students. A few weeks ago, I witnessed two lecturers at their wits end, fed up asking questions to large classes and receiving no answers. The rise of the online course. There is a frenzy of speculation over the rise of online degrees and teaching methods. Several latter-day prophets and moguls predict that education will soon be entirely internet-based, free (or cheaper) and distance-taught. I am filled with foreboding at the thought. I acknowledge that The Open University has existed for many years, and its students used to watch lectures on TV (indeed, I used to watch them at 6am when I was much younger). However, I think there is a two-fold problem with online education. How are students motivated into studying hard? How does the examiner know the student isnt cheating?

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

Laboratory sessions and presentations. Another concern with online education is the absence of real, co-ordinated practical laboratory work. This issue might not apply to management or other arts subjects. However, in engineering, sciences and computing, practical work is vital. Back in actual universities, I have noticed the time allotted to practical lab sessions (especially chemistry and biological laboratory work and fieldwork) seems to have diminished. Course leaders and university clerks bemoan that running laboratories and conducting experiments (with lots of machines and chemicals) is prohibitively expensive, and pose several H&S risks. I have attended science classes, where no laboratory sessions have been provided. This is a sad state of affairs, especially when science employers are baying for applicants with a long list of practical lab skills. Secondly, although many students deliver presentations to the lecturers and fellow students, I feel this should be done far more often, by individuals rather than groups. Im not suggesting that students should aspire to be TV presenters, and I know some intelligent scientists and programmers who are very shy individuals who suffer stage fright. However, a job interview is a sort-of presentation, and demonstrating your ideas and work is part of almost any job.

The control over information. Over the past five years I have sensed that university libraries have lost pride of place. Many students known to me have never been to one. The long rows of colourful academic journal periodicals are old and are receding. Brand new textbooks are rare, and sit beside rows of dusty, peeling old books. The commercial journal publishers have become the masters. They control access to journal papers. Universities have to purchase online licences so as to let certain students enrolled on certain courses access certain journal articles online. Only recent articles are available online, and older ones are concealed. Textbooks, more often than not, are now e-books, and are under the caprice of the source publisher or webmaster. The Google Scholar Search often yields spurious, irrelevant web pages. Another worrying symptom is that lecturers seldom write definitive textbooks, as they toil over the redrafted redrafts of redrafts of papers they are trying to publish in certain journals, which are owned by distant corporations thousands of miles away. Another sad aspect is the source of information. How wonderful it would be to hear a lecturer talk about what equipment she was using when she was working for the NHS as a consultant last year, or another lecturer teach students to construct a program similar to the one he had written for a software house. On that note, I do greatly appreciate the visits by some industry and NHS professionals to UWS to deliver lectures.

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

SOME PROPOSALS

The Aim I believe that the prime aim of any education course be it at school, college or university level is to motivate a pupil or student to focus, to read and write down information, and to memorise and understand it completely, before and during practical work. Once a student has mastered the ability to concentrate, read, collate, comprehend and remember information, then (s)he can start to think outside the box, and begin to apply logical thinking, gather further information and deduce solutions to problems. My proposals may be described as constructivist. Indeed, many of them are not entirely original.

You think, but do you know? My advisor of studies at the University of Glasgow challenged students with this question regularly. Geology students would tell him they had found some information, or speculated that the answer was in a certain book, or suggested a lab method for analysing a certain property of a chemical or rock formation. Dr Allison was never impressed. He would interrogate us, and identify whether or not we had actually learned anything, and whether or not we had actually read books or knew what we were doing. Today we are distracted by all manner of new technologies: online journal resources, search engines and citation databases; apps for producing, storing and uploading/downloading data; online class test systems such as the clicker multiple choice questions; desktop publishing and presentation software; internal university software for collating and publishing timetables, assessments and exam marks; communication systems including social network websites and mobile phone apps for group collaboration...the list is exhaustive. As a former chemist and unenthusiastic computer user, I just take one look at all those apps, programs and web pages, and ask a simple question: Will this new device make students transfer information into their brains? How much more information does the brain absorb today when we have all these mobiles, apps and websites...compared with 40 years ago when it was held in lecture notes and books? It is my opinion that in many Scottish universities today, lecturers and students waste far too much time playing with software, and not enough time actually absorbing and using information. There is only one way to remember information: write it down, cover it up, and recite it in your head and chant it back, and keep on doing this until you can remember. This may be a Stone Age technique, but it still works. Technology must simplify and accelerate a process. Sadly, software and apps are often enforced upon staff and students for their own sake, and can often complicate and prolong what used to be a simple task. Using a technology must help a student learn more about the subject, and not just about learning how to use the technology.

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

Figuring it out: example 1 It is amazing what our brains are capable of when we put our gadgets to one side. A few days before writing this, I was attending a science lab where the students were asked to calculate the standard deviation of their pipetting volumes. For years, I used MS Excel to calculate the standard deviation, not really thinking about what I was doing. I stood at the corner of the laboratory, bored (as a notetaker, I had almost nothing to do), and then began to ponder on the standard deviation. Is this a measure of the average deviation of values from either side of the mean? Of course I had long forgotten the equation, but I began to apply my thoughts logically as I saw an example of some values, the mean and a standard deviation value on a handout:

0.120 0.121 0.130 0.116 0.112 0.123 Mean = 0.1203 Standard deviation = 0.006

Obviously a calculator is needed to produce the mean value. However, I guessed that the standard deviation is the average deviation of the values away from the mean value. Some values are below the mean, so there will be some negative deviations. However, if we add negative deviations to some positive deviations, they cancel one another out, and the mean deviation would be almost 0. I was beginning to remember that the equation included the square of (value Mean)2...of course! I recalled that this was divided over n - 1 (the number of values - 1). And of course, all those squared deviations, once divided by n, needed to be square-rooted. I had figured out that long-forgotten equation:

Then I looked closely at the values, and figured that I could add and subtract them using only my head and a pen. I imagined that there was no zero or a decimal point, and so I treated the values as if they were somewhere between 1160 and 1300, and so:

0.1200 0.1210 0.1300 0.1160 0.1120 0.1230 0.1203: 0.1203: 0.1203: 0.1203: 0.1203: 0.1203: 1200 1210 1300 1160 1120 1230 1203 1203 1203 1203 1203 1203 = = = = = = -3 +7 +97 -43 -83 +27 therefore therefore therefore therefore therefore therefore -0.0003 +0.0007 +0.0097 -0.0043 -0.0083 +0.0027

Then I squared the numbers. Squaring decimal numbers is quite easy if you write the (number x 10-x) as (-x) becomes (-2x). Some numbers (e.g. 97) were easier to square using a calculator, but here goes:

-0.003 is -3 x 10-4 +0.007 is +7 x 10-4 32 = 9 72 = 49 (-3 x 10-4)2 = 9 x 10-(4+4) (7 x 10-4)2 = 49 x 10-(4+4)

...and so on until I had produced the following values:

9 x 10-8, 49 x 10-8, 9409 x 10-8, 1849 x 10-8, 6889 x 10-8, 729 x 10-8

10

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

I then imagined these as whole numbers and added them up:

9 + 49 + 9409 + 1849 + 6889 + 729 = 18934

...then reconverted the answer back to (x 10-8):

= 18934 x 10-8 or 1.8934 x 10-4

I then divided this by (no. of values 1), or 5 (admittedly, using a calculator), to obtain a value of 3.7 x 10-5. The standard deviation is 0.006, or 6 x 10-3. The rest is easy: 62 equals 36...and 3.7 x 105 is also 37 x 10-6. 37 is almost the same as 36, and so the square root of 37 x 10-6 must therefore be close to 6 x 10(-6) 2, which is 0.006.

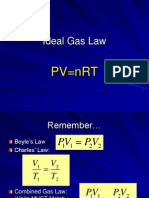

Figuring it out: example 2 This concerns proportions. In another recent class, I had to use the Ideal Gas Law, PV = nRT. (Pressure x Volume) is equal to (no. of moles of an element (e.g. carbon) x a constant x the temperature). I was having a task trying to convert various values into Fuel-Air ratios, masses of fuels (e.g. propene) and masses of air involved in a combustion reaction. This sounds hideous, but for now just focus the mind on the gas law. The volume of a gas is directly proportional to the moles (or amount) of a gas, and directly proportional to the temperature, and inversely proportional to the pressure. If you raise the temperature, the gas inside a balloon expands. If you pump more gas into a balloon, it expands. If you increased the pressure around the balloon, it shrinks. It is very simple! I didnt need to find this on Google. I worked it out in my head.

Logical thinking does not always save the day Real life is complicated, and real data is often muddled, detailed, and cannot always be categorised and simplified. There are times when one has to write down everything and just keep reading it and memorising it. My suggestion is try to memorise everything first, and then try to batch and condense the data later. Sometimes it may not even be possible to memorise everything. On the same day when I worked out the standard deviation backwards, I also noticed a large poster on the wall which listed all the dozens of white blood cells, lymphocytes and other cells in the lymphatic system (which fight bacteria and viruses). The table looked horrific. A few months earlier I was attending some immunology classes, and I was struggling to understand all the different terms, the different cells and their functions. Nothing seemed to match. The only thing I managed to understand is that some of these cells meet the antigens (which could be bacteria or viruses) inside little strands in the body called the lymphatic system; some other cells are chemical messengers signalling to some more types of cells which fight the little beasties. These are complicated processes, and the information has to be memorised in its entirety.

11

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

Lectorials I do not believe in long lectures. I believe that information should be shared and discussed among students, and that tutors should probe and challenge students reasoning in the classroom. I believe we should reject the old system of large assemblies of students filling a large room listening to someone droning on. Many school teachers will agree that small classrooms and interactive sessions are more effective. The lecturer should know his/her subject, but (s)he should make the students take responsibility in gathering and processing information. Here are my proposals: Each student should be attending at least one lectorial per day, Monday to Friday (delivered by different lecturers on various subjects). Each student group should consist of no more than 10 students. This will make it harder for lazy students to try and avoid answering questions. Students must carry notepads, pens and diaries to every class. engineering students must carry calculators. Science and

The session is not a place where the tutor reads a long list of notes. Both the tutor and the students should know the subject intimately. (The lecturer should not be one step ahead of the students, or made to lecture on unfamiliar topics.) Near the end of the lectorial, the lecturer (or rather, the tutor) introduces a topic, and speaks on it for about 10 to 15 minutes. The students all take notes. Then (s)he hands the students what I would term a shopping list of terms, concepts and ideas, which the students must investigate. For example, in a biomedical class, the tutor briefly describes the mechanisms affecting blood pressure, and issues a list of terms and sub-topics, which the students must investigate and learn, e.g. o Cardiac output, Systole, Diastole, parasympathetic and sympathetic and endocrine influences on heart rate, the Blood Pressure Equation, etc. The students spend the rest of the day in the library or online, investigating and gathering information, memorising equations and key facts, and practicing relevant calculations. At the start of the next lectorial, students must switch off their mobile phones, turn off their tablets and laptops, and place them in a deposit box on the agreement that they have promised to participate fully in the lectorial discussions and tests. The tutor will ask each student a question, and the student must either provide a verbal answer, or demonstrate/illustrate an answer using pen and pad, or using a whiteboard. This could even be artistic, e.g. a biomedical student must draw a diagram of the heart, showing all its major parts, or a diagram showing the sympathetic and parasympathetic influences on heart rate.

12

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

Students are awarded marks for punctuality, answering questions correctly, and showing an interest by asking further questions: o Each student is asked perhaps two to four questions, and is marked as follows (out of 3): Good effort, a detailed and correct answer: 3/3 A modest effort, but with some flaws in the answer or a lack of detailed information: 2/3 A poor or incorrect answer: 1/3 Uh, dont know = 0/3

o Students should be given bonus marks for asking questions and contributing to further discussion. Questions should be relevant and pertinent. Enquiries such as what time does this class finish or when do we get our marks for last weeks class test or wheres the loo do not qualify. o Attendance should form around a quarter or a third of the marks for each lectorial. If attendance is marked out of 2, then: Attendance before the start of the lectorial: 2/2 Slightly late attendance (up to 10 minutes into the session): 1/2 10 minutes into the session, the tutor should lock the door. Students who turn up more than 10 minutes late cannot enter the room, and lose both attendance and lectorial marks.

If students score less than 50% in a lectorial, they cannot progress onto the next one. They shall have to re-take a remedial lectorial assessment, and if they fail a second time, they shall have to withdraw from the course. This seems harsh, but I have encountered a similar system in the past. In the mid-1990s I sat some Scotvec modules at school, where I had to pass each class test or be discharged from the class. I failed one Scotvec Biology module and had to resit it (with a different set of questions). I failed a Scotvec Economics test and failed it a second time, and so I had to leave the classroom. I know it wasnt nice, and I had revised, but the simple truth was that I couldnt understand the subject. Lectorials should form at least a third of the potential marks awarded for a subject or to use the dreaded word the module. For theoretical subjects (e.g. management, social sciences) the value of the lectorial sessions should be even higher, maybe exceeding 50%.

Essays, reports and presentations: Dragons Den-style I believe that students deserve marks for the quality of their writing style and grammar, and the precision and neatness of diagrams, tables and graphs in written reports and essays.

13

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

However, I also believe that once they have written a piece, they should stand in front of a panel of examiners and defend their work. In my judgement, this is good preparation for the job interview room and the workplace. Again I must emphasise that students should present their work individually in front of the examining panel, even if they worked in small teams. A good example was when I worked with three students in my MSc class to design a water treatment plant: we each had certain aspects to investigate and design (e.g. removal of grit and dirt; heating and electrical power), and each one of us had to present our own findings and designs, and take questions from the floor. Students who ask questions should even be awarded bonus marks for very clever questions. (This marking system was used in the Dundee Institute of Technology back in the 1980s.)

Fast class tests, Old Driving Theory Test-style In 2000 I was one of the first people to sit the computer touch-screen driving theory test. It was a joke. I had to answer 35 multiple choice questions, and when I reached the end of the test, a screen appeared, showing me how many questions I had answered correctly: if I had answered less than 30/35 correctly, I had to navigate back and revisit the questions until I reached 30/35 within the one hour time limit. A year earlier, one of my friends was among the last people to complete the test using pen and paper. There was no software to indicate how many questions he had answered correctly. In fact, he failed on the first attempt, and so he revised hard, and passed the second time round. I do believe students should sit class tests and exams. However, students must be able to perform calculations and demonstrate a clear understanding of their subject within a short duration. Again, the aim here is to try and mimic the job interview situation, where an interviewer asks a question, and the applicant must provide an answer on the spot. One idea may be to set a 15-minute class test, where each student must answer a science or mathematical question, or a certain number of questions. The students should be able to remember the relevant equations, and be able to write out their working quickly within the time limit. As with lectorials, if a student fails a short class test, (s)he cannot progress further, and may be given a remedial class test, and if (s)he fails the remedial, (s)he has to withdraw from the subject or module. I would suggest at least one fast class test per month at the very least.

One-on-one short verbal exams Doctor in the House is probably one of the greatest and most influential films featuring student life. Near the end, the medical students must sit their exams. These include being interrogated by examiners in their offices on various medical subjects. In one examination room, a student is shown some jars containing body parts, and asked to identify them. In another, a student is asked to analyse body samples under the microscope and identify

14

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

them. In a third and more memorable exam, a student is quizzed by a professor who pretends to be a patient who is suffering from various symptoms. The student is asked questions, and he provides answers, and these lead to more questions, and further discussion until the student can identify the cause of the symptoms, and suggest what treatment is required. This, in my view, is one of the missing links in university. So for example, a biomedical student is asked to design a blood sample carrier, and describe how a blood sample is processed. (S)he enters a small examination room, where one of the lecturers holds up an ordinary plastic bottle, and says to the student, I want to collect a blood sample and then have it analysed. I am going to collect the blood in this bottle. Is this fine? To which the obvious answer is No. Why not? Is this not the right type of bottle? The student says no, and tells the lecturer that blood is collected in a special plastic bag. The lecturer asks further questions, e.g. what is the shape of the bag, what size, what volume, is there anything connected to it, what is the material, what labels should be placed on the bag, is a simple blood sample acceptable, or should it be a fraction, e.g. red blood cells only? The question and answer session continues for about 10 to 20 minutes until the student either provides an adequate solution, or time runs out.

Regular practical work (This applies mainly to computing, sciences and engineering) Education should be an active process, not a passive one. It requires more than sitting and watching movie clips, reading text and listening to someone droning. No IT or computer games/graphics company wants to hire someone who hasnt built several programs and demos and prototypes. No science lab or NHS branch will want someone who hasnt cut up body parts, or processed bodily fluids or analysed solutions in the lab. In a recent class, I witnessed some angry chemistry students expressing frustration after two and a half hours of someone reading off powerpoint slides. They didnt want to read about lab-work. They wanted to be in the lab, doing it for real. If only. Computing students have no excuse for not writing code and building programs and testing their own demos outside the lecture room. Laptops can be as cheap as 200, and it costs but a few pounds () for ones own internet browser and dongle device. I would suggest that prospective computing students must attend an entrance exam, where they demonstrate their own work, possibly as a portfolio website with demos, programs and even apps and games which can be purchased. It is harder for science and engineering students to be able to access a lab and perform practical work. It is illegal to set up a lab in the garden shed. Lecturers and students must complete a long batch of paperwork before the first bottles of solvent can be ordered. Not to mention that science labs are expensive. Todays regulations have rendered science and engineering courses so anodyne that practical lab sessions are few and far between. Biology students no longer dissect rats, and it wouldnt surprise me if medical students can no longer dissect a dead persons body.

15

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

A few months ago, I attended some microbiology labs where some 3 rd-year students were spreading some dangerous bacterial colonies onto agar plates. There was an excitement and tension in the air. These tiny luminous blobs were lethal. You could scrape off a blob and drop it into someones glass, and send him to the hospital. As a notetaker, I unnerved the lecturer and the lab technicians as I sat in the corner of the room. However, I knew that the students were having a great time. Whether it is computing, science, medicine or engineering, there should be regular practical work (even going out into the town or to a company site), every week. There should be practical sessions at least two days a week. Business studies students should be building their own companies, and visiting banks, agencies and conducting market research for real, even with clipboards on street corners. Computing students should be building programmes and selling products. Science students should be collecting, processing and analysing samples, even during the long summer months. Engineering students should be visiting construction sites, and should even be working on them during vacation, even as chain-boys or as brick-counters. Senior students should be supervising, and even leading, lab sessions for more junior students.

SOME MORE AMBITIOUS PROPOSALS

Fill up the long summer vacations with contract work Over the past few years, several people from IT companies and the NHS have informed me and my students that they are stressed out, and can only complete a certain amount of work. Forensic departments in the Scottish Police are being closed down or restructured, and according to one experienced forensics lecturer many samples collected at crime scenes are discarded. The NHS blood laboratories process millions of samples, and their technicians are overworked and have to make decisions on which samples deserve priority. Games companies are always on the lookout for freelance programmers, and many IT firms and other clients need a web developer or programmer to build a program on a short-term contract. The universities with their eager students should get involved. I believe that universities are failing students, not least because they are abandoned for five long summer months to sit at home and forget what they learned. Information which was corn-plastered into the mind during April and May fades away during June. Students return in October, and struggle to recall basic concepts taught a year earlier. Universities need to get serious and make themselves (and their students) indispensable. Departments should network with companies and organisations. Chemistry and biomedical departments should lease their labs to clients, which send in samples (of a medium or low priority), which staff and (the more competent) students can analyse, particularly over the summer. Departments can charge for these services, and many students will be more than willing to process real samples for real clients. They can build portfolios as well as accrue module credits.

16

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

Employers nearly always demand applicants with 3+ years of relevant experience. At the time of writing, very few biomedical, chemistry and engineering graduates can secure jobs. A few (larger) organisations may cast a marbled eye on young school-leavers and graduates, and offer the occasional apprenticeship. This approach has gone badly wrong in some cases. Perhaps the worst has been the recent scandal of local authorities taking on PGCE trainee school-teachers, and then making them redundant after two years. Do away with the 1st, 2:1, 2:2 and 3rd class rankings Employers do not really care about the level of degree attained. Many recruiters will insist that applicants possess a 2:1 degree or better, but deep down, they are not really interested in the ranking. Furthermore, a 2:2 degree from Edinburgh or Imperial College may be valued more than a 2:1 degree from, e.g. Glasgow Caledonian University or Abertay. (I am not casting any judgement here.) Many years ago when I was searching for placements (alongside my BSc course), I used to display all the marks I achieved in all my subjects. This can be more revealing. Furthermore, employers may be interested to learn how well the student performed, relative to the rest of the class. If someone came 4th or 2nd in a class, I am sure many recruiters will keep reading through the rest of his/her resume. I do not believe in the 1st, 2:1, 2:2 and 3rd class categories. A first class graduate is either a geek, or someone who worked day and night. Why is the second class grading split into 2:1 and 2:2? We tend to think that a 2:1 graduate is not quite a geek but did well, whereas a 2:2 graduate was either slightly incompetent or slightly idle. There is a general consensus that a 3rd class graduate is incompetent and idle, but managed to stumble into the university and write something. We need to do away with this. In my judgement, students either pass or fail. Can they be trusted by an employer? Are they intelligent, reliable and competent? Are they self-disciplined and mature? Can they analyse with precision, and write reports of a high quality? Can they understand complicated information, and be able to sift through it, and use their knowledge and reasoning to solve problems, and convey ideas to a client or a patient? Can they work alone or within a team to build a product or provide a service? Is the student a safe pair of hands, as far as the employer is concerned?

Condense degree programmes Not so long ago, UWS, Abertay and many other universities were colleges, which offered shorter, more vocational courses. I am not going to write about the political squabbles over the old binary line. I will state briefly that there was a time when not every school -leaver was expected to go to university and spend three to five years reading for a degree. More poignantly, UWS was once the Paisley Institute of Technology, which at one time was one of the best technical colleges in the country.

17

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

Not every discipline demands four years spent away from home surviving on a student loan and trying to support oneself by flipping hamburgers and stacking shelves. Medicine and Law are extremely difficult subjects, which take years to master. Programming, chemistry and engineering disciplines (e.g. architecture) could be condensed to three or even two years, and may not need to be accorded a BSc title. I believe that students should not be teenage school-leavers who enter into this rite of passage of leaving home, getting drunk and trying to balance studies with some part-time job. I remember starting my BSc course at age 17; I was a naive, ignorant prat who talked a load of drivel half the time, who possessed no real world experience. I may have attended classes and passed my exams, but I was not ready. I knew nobody in industry. I did not understand the importance of extra-curricular achievement. I kept wondering what I needed to know, and not asking myself why I needed to know something. University should be for more mature, intellectually brilliant people who can pass entrance exams and demonstrate a passion for their subject. I think someone leaving school should spend a few years saving up the money, trying to gain some relevant experience, and then try and enter university. I also do not see why nearly all students should be under-25. I think anyone between 20 and 60 should apply (and only the smartest get in). Perhaps it is time to break away from the late September to May format. Courses should run throughout the year, but for maybe two or three years. Or, classes (lectorials, etc) should run from September to June, and contracting work should run during the summer. Either way, students should not be sitting idle for half the year.

Research as a means to an end Research and teaching are two different mistresses. I am not opposed to lecturers having to conduct and publish research. However, the two duties should not be allowed to overlap to the point where the one cancels out the other. One idea may be for lecturers to teach from September to May, and conduct research during the summer. Research should include visiting sites and offices in industry, and finding out what employers demand from graduates, and what help is required. An example is a biomedical lecturer investigating the latest laboratory techniques, and maybe offering to develop a new technique in the university lab and hiring some students to process a batch of samples. Furthermore, lecturers should be writing textbooks and publishing their notes as books or ebooks or blog sites. I feel that peer-reviewed journal paper publishing is overrated, and has become an end in itself. In theory, the journal paper publishing exercise ensures that only very high-quality, accurate work can be promoted. Sadly, it is also a rather nepotistic exercise. If your project leader is a professor with a long list of previous publications (many of them written by other people), then of course your paper will be published. Many journals host papers written by a conclave of usual suspects. I am not suggesting that trying to publish an actual book is much fairer; we have heard many tales of famous authors struggling to persuade publishers to consider their works, and some having their work rejected by dozens of wary publishers.

18

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

I admit that this matter is off-tangent, and there are many pros and cons with publishing research using other methods. However, it is time to acknowledge that the RAE and REF exercises have been detrimental to teaching, as enthusiastic tutors are told that helping students is not a priority, and weary lecturers are made to cancel classes, and paperpublishing post-docs are imported into the lecture room to teach a bit on the side before running back to the office to redraft the redraft. Not to mention (as I have observed on many occasions) that several journal papers are regurgitations of early papers and conference proceedings. Research should assist students and be of use to the nation. We need lecturers to visit industry, analyse what is happening out there, work with potential employers, and update their knowledge of the subject in books and other notes. I do agree that research writings should be subject to review. Nowadays, online blogging and fora websites allow for people to submit comments underneath articles.

IN CONCLUSION

Universities are different from most private sector and public sector workplaces. They are hubs for the stimulation and training of great minds. They should be led by some of the smartest people in the country, and should attract only the smartest applicants. University education and research runs on thought. Money, mechanical and electrical power and manual effort are the prime drivers in most other employment sectors. The shelf-stackers must shift merchandise quickly. Van drivers must plot the fastest route from one drop point to the next and the rest is up to the vehicle. Many public sector workers fill forms and work to meet specified targets. The university is different. It survives on allowing lecturers and students the liberty to sit in a quiet place, to read, to contemplate, to design, generate and test theories and data. Universities face a growing threat from online education methods. However, interaction is an essential tool in training students, and inducing them to think on the spot and focus their minds on the subject. The biggest threat to university education comes not from the internet, but from distractions. Technologies have their uses, but in recent years they have proved a burden, and scholars waste too much time trying to reformat files, upload other files onto online data systems, or rebooting computers, or using an obscure app or program just to view an internal file, when only a few scribbled notes on a sheet of paper are required. Journal paper publishing has become a higher priority than teaching, and many academics waste a disproportionate time on redrafting redrafts of papers, which will be read by very few people. Internal university bureaucracy has further suffocated teaching quality. If universities are to survive, then the student (as the customer and fee-payer) must come first, and teaching must be the prime function, and prospective employers should be the ones who review the work by the academics. Furthermore, academics must not be tethered

19

Teaching students to remember, understand and use knowledge

into passing students in order to prove that the majority of a class can pass each and every module. If a student is incompetent or lazy, (s)he must fail, and must take the lions share of the blame. Entrance exams should be restored, and the grading and length of degree courses also need to be questioned. Learning is about absorbing and understanding information, and students must be directed to doing this. In the science, computing and engineering fields, the importance of practical work cannot be underestimated. Students must be working on something stimulating and relevant throughout the year, particularly in the summer months. It is time to combat the persistent interference from bureaucrats, and the deluge of forms and procedures which are not integral to teaching students. The universities where I have worked have become warehouses; ruled by audaciously rich principal-managers above layer after layer of middle-managers; packed to the gills with students, who are seldom regarded as anything more than bums on seats; where clerks outnumber the academics; and where teaching staff cannot even mark their own students honestly. Every hoop, every tick-box, every form, every intradepartmental meeting and every target (e.g. 70% of students must pass first year) reduces thinking time, both for the academic and the student. Tutors and supervisors should be answerable to no-one save the students, and to prospective employers in relevant industries. Students and tutors alike should supervise lab sessions, run the libraries, and even perform menial duties including cleaning and maintenance. If universities are to survive, then academics must take back the powers they have lost, students must be tested vigorously, and industry must play a direct role. It is time to reinstall vigour and honesty within the university, and to lift the caps and inhibitions which distract and prevent students from absorbing information and preparing for the workplace. A university exists to keep the lamps of learning and truth trimmed and bright. Our task is to follow truth, and to maintain standards. (Rt. Hon. Stanley Baldwin)

20

You might also like

- Mike's Videos - General Chemistry Lesson Outline PDFDocument63 pagesMike's Videos - General Chemistry Lesson Outline PDFAmandaLe50% (2)

- The Essential Teaching Skills Ebook PDFDocument11 pagesThe Essential Teaching Skills Ebook PDFBaiquinda ElzulfaNo ratings yet

- Ib History Guide 2017Document108 pagesIb History Guide 2017api-288127856No ratings yet

- Ideal GasDocument12 pagesIdeal GasJasminSutkovicNo ratings yet

- Essays Reading TeqnuichesDocument177 pagesEssays Reading TeqnuichesoltjanaNo ratings yet

- Seven Principles For Good Teaching - University of Tennessee at Chattanoog104603Document15 pagesSeven Principles For Good Teaching - University of Tennessee at Chattanoog104603Majeed MajeedNo ratings yet

- Mini Thesis TitleDocument5 pagesMini Thesis Titlesupnilante1980100% (2)

- International Development Spring 2024 updatedDocument13 pagesInternational Development Spring 2024 updatedeynullabeyliseymurNo ratings yet

- Mini Thesis FormatDocument4 pagesMini Thesis Formatjenniferperrysterlingheights100% (2)

- Skip To Main ContentDocument20 pagesSkip To Main ContentSher AwanNo ratings yet

- Pathways to Professorship: A Career Guide for Aspiring AcademicsFrom EverandPathways to Professorship: A Career Guide for Aspiring AcademicsNo ratings yet

- Student Engagement Strategies For The ClassroomDocument8 pagesStudent Engagement Strategies For The Classroommassagekevin100% (1)

- Literature Review On Educational FacilitiesDocument7 pagesLiterature Review On Educational Facilitiesafmzfsqopfanlw100% (1)

- Research Template by Zeynep SomuncuDocument7 pagesResearch Template by Zeynep Somuncuapi-644146694No ratings yet

- Community College CourseworkDocument7 pagesCommunity College Courseworkcprdxeajd100% (2)

- Blue Book 2020 Revised IIDocument16 pagesBlue Book 2020 Revised IItorquerxfNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Template Week 10 Kanuni Research Assignment 5Document4 pagesResearch Paper Template Week 10 Kanuni Research Assignment 5api-302410946No ratings yet

- Quality Qualified, Which Students Cannot Gain by Self-StudyingDocument2 pagesQuality Qualified, Which Students Cannot Gain by Self-StudyingDat NguyenNo ratings yet

- Ta HB Ch2 Teaching StrategyDocument20 pagesTa HB Ch2 Teaching StrategyvicenteferrerNo ratings yet

- Research Assignment 5 - Rasim DamirovDocument3 pagesResearch Assignment 5 - Rasim Damirovapi-302245524No ratings yet

- The Hidden Curriculum of Dissertation AdvisingDocument6 pagesThe Hidden Curriculum of Dissertation AdvisingHelpWritingACollegePaperYonkers100% (1)

- University of Washington Online LearningDocument6 pagesUniversity of Washington Online Learningapi-259632481No ratings yet

- Research or Coursework MastersDocument8 pagesResearch or Coursework Mastersbcr9srp4100% (2)

- Thesis Topics On Distance EducationDocument5 pagesThesis Topics On Distance Educationh0nuvad1sif2100% (1)

- Kindly Work On Your Assigned Area of The Syllabus For Purposive CommDocument6 pagesKindly Work On Your Assigned Area of The Syllabus For Purposive CommNeo ArtajoNo ratings yet

- Dutoit Trajectories 2020Document131 pagesDutoit Trajectories 2020Sasha-Lee KrielNo ratings yet

- Overview of The American University ClassroomDocument4 pagesOverview of The American University Classroomapi-288361278No ratings yet

- Master Coursework UumDocument5 pagesMaster Coursework Uumd0t1f1wujap3100% (2)

- Research Paper About Tardiness in SchoolDocument8 pagesResearch Paper About Tardiness in Schoolafmchxxyo100% (1)

- Thesis Title For High SchoolDocument5 pagesThesis Title For High Schoolgqdknjnbf100% (1)

- Social Work Unsw Course OutlineDocument5 pagesSocial Work Unsw Course Outlineafiwjkfpc100% (2)

- Curriculum: ImportanceDocument3 pagesCurriculum: ImportanceMohsin AliNo ratings yet

- Primary Education Dissertation TitlesDocument4 pagesPrimary Education Dissertation TitlesHelpWithWritingPaperSingapore100% (1)

- Nature and Scope of Distance EducationDocument7 pagesNature and Scope of Distance EducationhabibshanglaNo ratings yet

- Formal EducationDocument5 pagesFormal EducationAliza Therese ReyesNo ratings yet

- Assignment 3 ReportDocument11 pagesAssignment 3 ReportDaniel AdebayoNo ratings yet

- Study Habits of Bsa Students at Tip-ManilaDocument44 pagesStudy Habits of Bsa Students at Tip-ManilaJodie Sagdullas88% (56)

- 101 Things You Can Do The First Three Weeks of ClassDocument16 pages101 Things You Can Do The First Three Weeks of ClassvelumanijayaramanNo ratings yet

- Subject - Reflection On The Advanced Writing CourseDocument6 pagesSubject - Reflection On The Advanced Writing CoursePham Ngoc Phuoc AnNo ratings yet

- Large Classes Teaching GuideDocument26 pagesLarge Classes Teaching GuidesupositionNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Student EngagementDocument8 pagesDissertation Student EngagementProfessionalPaperWritersUK100% (1)

- f64d6 Ys6owDocument33 pagesf64d6 Ys6owManjares, Erika R.No ratings yet

- Practical Research 2Document14 pagesPractical Research 2Reymark ReyesNo ratings yet

- EDUC 105 Facilitate Learning ModuleDocument61 pagesEDUC 105 Facilitate Learning ModuleLoren Marie Lemana AceboNo ratings yet

- EDACE 714 International Education Syllabus-FinalDocument26 pagesEDACE 714 International Education Syllabus-FinalNaydelin BarreraNo ratings yet

- Tap 201 Suleiman Muriuki Cat 1Document6 pagesTap 201 Suleiman Muriuki Cat 1Ryan PaulNo ratings yet

- Term Paper Classroom ManagementDocument7 pagesTerm Paper Classroom Managementc5j2ksrg100% (1)

- Principles of Teaching Term PaperDocument4 pagesPrinciples of Teaching Term Paperc5j2ksrg100% (1)

- Handout To Accompany Interactive Presentation On Integrated Aligned Course DesignDocument6 pagesHandout To Accompany Interactive Presentation On Integrated Aligned Course DesignIlene Dawn AlexanderNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Titles For Early Years EducationDocument8 pagesDissertation Titles For Early Years EducationPayToWritePapersUK100% (1)

- Higher Education and Online EducationDocument16 pagesHigher Education and Online Educationcatalin barascuNo ratings yet

- Increasing Undergraduate Involvement in Computer Science ResearchDocument8 pagesIncreasing Undergraduate Involvement in Computer Science ResearchvvmmrrNo ratings yet

- How To Make A Teaching StatementDocument10 pagesHow To Make A Teaching StatementNedelcuGeorgeNo ratings yet

- A Traditional Approa To Tea Ing: Flipping The Photography ClassroomDocument6 pagesA Traditional Approa To Tea Ing: Flipping The Photography ClassroomCristian Rizo Ruiz100% (1)

- Coursework of PHDDocument7 pagesCoursework of PHDf5a1eam9100% (2)

- Tips For Succeeding As A New Engineering Assistant Professor Draft Paper Final VersionDocument12 pagesTips For Succeeding As A New Engineering Assistant Professor Draft Paper Final VersionbinzbinzNo ratings yet

- Research Paper About Education TopicsDocument8 pagesResearch Paper About Education Topicsgbjtjrwgf100% (1)

- Midterm Exam - Sci Ed 223Document3 pagesMidterm Exam - Sci Ed 223Jhonel MelgarNo ratings yet

- Research Paper About Absenteeism in SchoolDocument7 pagesResearch Paper About Absenteeism in Schoolcan8t8g5100% (1)

- Dissertation Action ResearchDocument5 pagesDissertation Action ResearchBuyCheapPaperNorthLasVegas100% (1)

- The Principles That Facilitate Successful and Timely Degree CompletionFrom EverandThe Principles That Facilitate Successful and Timely Degree CompletionNo ratings yet

- The Economist’s Craft: An Introduction to Research, Publishing, and Professional DevelopmentFrom EverandThe Economist’s Craft: An Introduction to Research, Publishing, and Professional DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Waste Characterisation Literature ReviewDocument41 pagesWaste Characterisation Literature ReviewDr Malcolm Sutherland100% (1)

- IPPC Report For A Glass Manufacturing Factory, Montrose, ScotlandDocument23 pagesIPPC Report For A Glass Manufacturing Factory, Montrose, ScotlandDr Malcolm SutherlandNo ratings yet

- Issues Concerning The New Abstraction Sites at Buckland, Primrose and Elms Vale.Document54 pagesIssues Concerning The New Abstraction Sites at Buckland, Primrose and Elms Vale.Dr Malcolm SutherlandNo ratings yet

- Tenerife: Formation, Stratigraphy and Water ResourcesDocument25 pagesTenerife: Formation, Stratigraphy and Water ResourcesDr Malcolm SutherlandNo ratings yet

- Glenrothes 1948 To 1998. A Geographical Study of The 'New Town' in Its 50th Year. Malcolm Sutherland, 1998Document21 pagesGlenrothes 1948 To 1998. A Geographical Study of The 'New Town' in Its 50th Year. Malcolm Sutherland, 1998Dr Malcolm SutherlandNo ratings yet

- Counter-Urbanisation in Chicago - Can This Be Overcome? Malcolm A Sutherland, 1998Document25 pagesCounter-Urbanisation in Chicago - Can This Be Overcome? Malcolm A Sutherland, 1998Dr Malcolm SutherlandNo ratings yet

- Topic 3.2 - Modeling A GasDocument49 pagesTopic 3.2 - Modeling A GasPaul AmezquitaNo ratings yet

- Https - Scholar - Vt.edu - Access - Content - Group - Exam Keys - Test 4 Form B Solutions PDFDocument18 pagesHttps - Scholar - Vt.edu - Access - Content - Group - Exam Keys - Test 4 Form B Solutions PDFEmmett GeorgeNo ratings yet

- 5 6190716459740561759Document157 pages5 6190716459740561759MD ARMAGHAN AHMAD0% (1)

- The Gas Laws: Porschia Marie D. Rosalem, LPTDocument48 pagesThe Gas Laws: Porschia Marie D. Rosalem, LPTGio Rico Naquila EscoñaNo ratings yet

- Othe Gas LawsDocument20 pagesOthe Gas Lawsromavin guillermoNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1Document48 pagesLecture 1vivekNo ratings yet

- MALIK Phy Kinetic TheoryDocument34 pagesMALIK Phy Kinetic TheoryShadab HanafiNo ratings yet

- 101 GasesDocument6 pages101 GasesQaz Zaq100% (1)

- Handouts Gas Laws and Chemical ReactionsDocument5 pagesHandouts Gas Laws and Chemical ReactionsMary Rose AliquioNo ratings yet

- Objective Chemistry Gear UpDocument42 pagesObjective Chemistry Gear UpmohamedNo ratings yet

- CLS Aipmt-18-19 XIII Che Study-Package-2 SET-1 Chapter-5 PDFDocument46 pagesCLS Aipmt-18-19 XIII Che Study-Package-2 SET-1 Chapter-5 PDFعمران ابن مشرفNo ratings yet

- SG 74CalculatingK 61d7d001d3dfd1.61d7d005b55853.96045589Document27 pagesSG 74CalculatingK 61d7d001d3dfd1.61d7d005b55853.96045589任思诗No ratings yet

- Van Der WallsDocument24 pagesVan Der WallsAnonymous oVRvsdWzfBNo ratings yet

- Satish Chandra: Unit - I, Real GasesDocument6 pagesSatish Chandra: Unit - I, Real GasesSanchari BiswasNo ratings yet

- How To Convert To and From Parts-Per-Million (PPM) PDFDocument6 pagesHow To Convert To and From Parts-Per-Million (PPM) PDFrizanindyaNo ratings yet

- Physical Behavior of Gases: Kinetic TheoryDocument12 pagesPhysical Behavior of Gases: Kinetic TheoryPAUL KOLERENo ratings yet

- Kinetic Theory of GasesDocument6 pagesKinetic Theory of GasesSecret SantaNo ratings yet

- National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST) : Lab ReportDocument6 pagesNational University of Sciences and Technology (NUST) : Lab ReportMohammad SalehNo ratings yet

- Chem Lab ZN Al AnalysisDocument3 pagesChem Lab ZN Al AnalysisZack Ploen0% (1)

- Part II Introduction To ThermodynamicsDocument30 pagesPart II Introduction To ThermodynamicsLeon MyselfNo ratings yet

- Science10 - Fourth - QTR - Module - 1 - de Jesus - L1Document16 pagesScience10 - Fourth - QTR - Module - 1 - de Jesus - L1Helma Jabello AriolaNo ratings yet

- An Accurate Method For Determining Oil PVT Properties Using The Standing-Katz Gas Z Factor ChartDocument105 pagesAn Accurate Method For Determining Oil PVT Properties Using The Standing-Katz Gas Z Factor ChartSuleiman BaruniNo ratings yet

- Ideal Gas LawDocument25 pagesIdeal Gas LawAndreea Ella100% (1)

- 1 Gases and LiquidsDocument41 pages1 Gases and LiquidsElisha LabaneroNo ratings yet

- Ch14 The Ideal Gas Law and Kinetic TheoryDocument54 pagesCh14 The Ideal Gas Law and Kinetic TheorysugarfootgalNo ratings yet

- Wichert AzizDocument8 pagesWichert AzizkroidmanNo ratings yet

- SCIENCE Q4 NotesDocument2 pagesSCIENCE Q4 NotesKyshley VargasNo ratings yet

- Behavior of GasesDocument4 pagesBehavior of GasesDuaneNo ratings yet