Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Taylor-Limbs of Empire

Taylor-Limbs of Empire

Uploaded by

bill6371Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Taylor-Limbs of Empire

Taylor-Limbs of Empire

Uploaded by

bill6371Copyright:

Available Formats

Christopher Taylor

The Limbs of Empire: Ahab, Santa Anna, and Moby-Dick

n June 1847, P. T. Barnums American Museum opened an exhibition featuring the captured prosthetic limb of General Antonio Lpez de Santa Anna, notorious leader of the Mexican army during the U.S.-Mexican War. The leg was brought to New York from the battlefields of Mexico and displayed before a sensationalized public who wrote, sang about, and went to see the generals wooden leg.1 Herman Melville, fascinated by Barnum and his representational practices, wrote a piece for Yankee Doodle on the life-sized exhibition of the great Santa-Anna Boot.2 Les Harrison has recently argued the importance of Barnums cultural practices to Melvilles novels, finding parallels between the American Museum and that thing of trophies, the Pequod.3 Like a museum, Moby-Dick collects and gives stories to things strange and quotidian, sampling and displaying U.S. and oceanic material culture in much the same way that the novels preface, Extracts, samples the bibliographic history of whales. What if, however, Moby-Dick did not simply incorporate the object epistemologies of museums but also incorporated the objects themselves? What if the dismasted captain Ahab is perched atopin a nearly literal fashionthe captured cork of General Santa Anna? Following Elaine Freedgood, I am suggesting a literal approach to the literary thing,4 yet Moby-Dick presents numerous challenges to this interpretive stance. From its title, the novel folds the literal into the literary, prioritizing the latter but opening space for a hermeneutic decision: Moby-Dick or the Whale?5 With Ishmael, readers oscillate between John Locke and Immanuel Kant, between the material and the metaphoric, between literal and literary reading modes ( MD, 357). The stakes are not merely epistemological; the loss of the literal is the

American Literature, Volume 83, Number 1, March 2011 DOI 10.1215/00029831-2010-062 2011 by Duke University Press

30American Literature

context in which the Pequod s tragedy unfolds. Starbucks feckless attempt to disenchant the whalea dumb thing, he claimslacks the affective and symbolic power of Ahabs figuring of that inscrutable thing ( MD, 178). Although the position Starbuck takes is unviable, the antinomy he establishes calls attention to the process and the politics by which things are deliteralized and figured. If the material is always already metaphoric, if the literal is always becoming literary, what are the politics of this process? What are the effects, and affects, of deliteralization? Freedgood advocates examining the literary thing in terms of its own properties and history and then refigur[ing it] alongside and athwart the novels manifest or dominant narrative.6 Yet to follow the literal history of Santa Annas prosthesis is to track the constant loss, as Freedgood would say, of its specific qualities and of its literal referent.7 The prosthetic thing appears in the archive as already determined by the narrative demands of empire; the figures of empire fill the gap left by the loss of the literal. Through the representational practices of people like Barnum, the generals leg, far from indexing his loss, figured the triumphs of empire building. It is this process of imperial metaphorizationa subtraction by addition, where the literal is lost by supplementing it with the prosthesis of figurative meaning that Moby-Dick engages.8 As The Quarter-deck chapter suggests, the surplus of the symbol is never simply an enchanted thing but a community that participates in and maintains the things figurative power. Moby-Dick, I argue, inscribes the process of deliteralization and figuration to which Santa Annas prosthesis was subject, attending to the power of things to produce and subordinate what he will call, on the outbreak of the war, the democratic rabble.9 Melvilles attention to the figurative work by which this material thing socially mattered necessitates rethinking the relationship between the text and the history with which it engages. Michael Paul Rogin proposes that MobyDick is irreducible to political-historical allegory insofar as Ahab himself renders allegorization an immanent aspect of the novel.10 Other scholars, refusing the grandeur of the allegorical, have unearthed dizzying and significant correspondences between the text and its context. Given the geographic and referential promiscuity of Moby-Dick, its context can extend endlessly, as evidenced by the important work of recent transnationally oriented scholarship that centers the Pequod s narrative in Japan, the Pacific, Latin America, South Asia, and so on.11

Ahab, Santa Anna, and Moby-Dick31

Although my reading draws on these approaches, it also suggests that Melvilles engagement with the social history of Santa Annas prosthesis calls for a displacement of focus. The link between Moby-Dick and imperialism in Mexico is more intimate than Ishmaels transfiguration of the ocean into a frontier prairie, or his rhetorical dismissal of the United States desire to add Mexico to Texas ( MD, 70). The novel does not just reflect, encode, correspond to, or offer a literary interpretation of an ontologically prior historical narrative but exposes the rhetorical figures that governed the symbolic economies through which the social text of the period known as the American 1848 was produced and cognized. In his engagement with Santa Annas prosthesis, Melville plays the part of a Russian formalist, revealing the rhetorical devices through which the limb gained its social meaning, while indicating that the particular figures Barnums exhibit deployed offer a hermeneutic for reading the social more broadly. Moby-Dick reads the figurative career of Santa Annas prosthesis to reconstruct the politics and political effects of the figures through which the social world of the American 1848 was constituted, thought, and reshaped. The process of industrialization, the rise of wage relations, the declining viability of independent artisan labor, and the concomitant formation of an urban working class structured the New York social world that Barnum and Melville inhabited.12 Resisting these changes, members of both the radical and popular sections of the working class developed racial and nationalist cultural forms through which they critiqued their dependence on industrial capitalism.13 Intertwined with nationalist and racial rhetoric, figures of bodily disability and loss underwrote working-class critiques of the heteronomy of capitalism and of wage slavery. While Jacksonian workers asserted a regenerative white national identity against the disabling effects of capitalism, U.S. elites deployed figures of bodily and fiscal injury to justify expansion into Mexico. Generating popular support for the war, this rhetoric of national loss captured and redirected the figures by which the working class critiqued capitalism: the prosthetics of empire offered the autonomy sought by workers resistant to debilitating industrial labor.14 For Melville, Barnums display of Santa Annas prosthesis exposes the uneven articulation of the working-class rhetoric of disability and regeneration with the elite language of loss and indemnity. Moby-Dick narrates, I argue, how hegemonic redeployments of the working-class rhetoric of loss transformed the hands of industry,

32American Literature

seeking autonomy through an imperial prosthetic, into the prostheses of an Ahabian empire.

Figuring the Prosthetic / The Prosthetic of the Figure

In 1839, France invaded Mexico in order to secure the property and investments of French nationals. In a proleptic enactment of the future U.S. rationale for invasion, France cited as its casus belli the necessity of gaining indemnification for damages done by Mexican citizens.15 General Santa Anna, disgraced since his defeat at the hands of Anglo colonizers in Texas, took the French invasion as a chance to restore his political and military reputation. This restoration came at a great cost, however: during action at Vera Cruz, he lost his left leg. In a public relations maneuver anticipating Barnums capitalization on its prosthetic replacement, Santa Anna had his amputated limb placed in a crystal jar and buried beneath a gaudy monument in a cemetery near Mexico City. Having suffered bodily loss in the defense of his nation against the French imperial power, he parlayed this obvious sign of his patriotism into power in Mexican political life.16 News of Santa Annas injury traveled to the United States through a variety of media. Anecdotes about it were published in Frances Caldern de la Barcas extraordinarily popular Life in Mexico (1843), a text Melville owned.17 Discussions of Santa Annas missing legand his ostentatious memorial to itwere set pieces in U.S. travelers accounts of Mexico,18 and this interest would continue into the 1850s and well beyond.19 For a reading public accustomed to the exotic stories composing William H. Prescotts successful Conquest of Mexico (1843), the tale of Santa Annas lost leg provided contemporary reenactment of a romantic hemispheric past.20 Interest in the leg, however, exceeded its anecdotal value. For proimperial U.S. Americans, the memorial to the leg was a moment of figurative excess in which Santa Anna illegitimately appropriated loss as a gain, generating symbolic surplus from material remains. Along these lines, Albert Gilliam records his experiences in the cemetery where the leg was buried: But what diverted my respect from the consecrated place in a considerable manner, and almost annihilated the effect of the useful lessons which the cemetery had impressed upon my mind, of human life and its end, was the beholding the pride and pageantry of a

Ahab, Santa Anna, and Moby-Dick33

monument, surmounted with the arms and the flag of Mexico floating from its corners, over the mortal remains of the left leg of the immortal Dictator, Santa Anna. The hero must excuse me, for since his leg has become public property, it cannot escape comment, and that too will be made, with blame or praise, as freely as his own deeds, just as his person will be eulogized after he himself shall have descended to the tomb.21 As Gilliam reads it, Santa Anna established a perverse synecdoche between his leg and his person, assigning his lost part the affective status of a fully dead body. The authority Santa Anna derived from this display is illegitimate because catachrestic; his personal and literal loss is placed improperly within a national symbolic economy, assuming a metaphorical value that exceeds the value of other Mexican bodies. Gilliam thus takes delight in describing what he codes as patriotic vandalism: One of the flag-staffs of the monument was broken down, perhaps by some one of his countrymen more daring than the rest, to retrieve the honour of his countrys flag, and show his opposition to the highest authority upon earth.22 George Wilkins Kendall similarly casts Santa Annas memorial to his leg as an improper capitalization on his loss: [A] general holy-day was given, and the limb was borne about in procession with great pomp and ceremony. Santa Anna makes much capital out of this affairenough to console him, probably, for the loss of the limb. On several occasions it has been carried about in procession, and I have little doubt that the leg, in pickle, is of infinitely more service to him than when attached to his own proper person.23 Once more, the generals leg signifies catachrestically, gaining a referential power infinitely more than it possessed when its semiosis was appropriately tied and subordinated to Santa Annas own proper person. The general, Kendall suggests, symbolically speculates on his limb, appropriating a surplus capital from his bodily disappropriation. Playing the role of an imperialist Starbuck, Kendall codes Santa Annas attempt to form a national community of mourning as an inappropriate prosthesis for the loss the general suffered in antiimperial warfare. The general, however, had prostheses other than the political symbolic. Santa Anna had a prosthetic limb manufactured by a Yankee

34American Literature

cabinetmaker from New York, and unlike Ahabs leg, it was tricked out with all the bells and whistles prosthetic science could afford. He purchased two of these high-tech legs for $1,300 a piecea massive personal expenditure.24 Indeed, Santa Annas loss came at a good time, for the ability to provide mechanical compensation for lost parts was progressing radically.25 As the science developed, so too did an ideological discourse on prosthetics, in which mechanical limbs materialized the regenerative, autonomy-giving effects of liberal capitalism and industrial manufacture. Benjamin Franklin Palmer, for instance, made important advances in prosthetics, and his leg drew much buzz in U.S. mechanical and medical journals, at several regional and national industrial exhibitions, and at houses of progressive science like the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia.26 In its account of the Washington fair at which Palmers leg was exhibited, Fishers National Magazine argues that the collection of goods on display is evidence of not a mere political independence, but a solid substantial independence, founded upon a supply of our own wants. The writer boasts of the great bulk of American manufactures which . . . are circulating throughout the Union, sustaining not only the one million or more persons who are constantly engaged in their fabrication, but giving life, animation and vigor to an immense internal trade . . . .27 If industry in general secured substantial freedom for the nation, the specific manufacture of prostheses offered a second freedom to those who experienced a loss. The reviewers at the Franklin Institute noted that Palmers leg was nearly self-acting: it could restore wearers to autonomy.28 Prosthetics offered a figure of liberal capitalism in which markets quite literally would restore autonomy to individuals and nations.29 For U.S. American readers, Santa Anna was figured as possessing two prostheses: the national community and power that symbolically supplemented his loss, and the self-acting manufactured limbs he purchased from New York. When the generals limb was captured, however, the two symbolic registers were conflated: to capture Santa Annas wooden leg was to conquer the Mexican nation, to appropriate the means whereby the general restored himself to autonomy. In 1847, the Fourth Illinois Regiment happened upon Santa Annas carriage during the battle of Cerro Gordo. Santa Anna and his party had abandoned their goods in their hasty, sudden flight, leaving behind several thousand dollars in gold as well as Santa Annas spare pros-

Ahab, Santa Anna, and Moby-Dick35

thetic leg.30 When the regiment seized the leg as a curious trophy, ensuing cultural productions shifted the meanings ascribed to prostheses. Palmers prosthesis had materialized ideologies of peaceful liberal capitalism, suggesting that northeastern markets and manufacturers could regenerate the nation. The discourse surrounding Santa Annas captured leg, however, intimated that militarism and territorial expansion could regenerate subjects whose autonomy seemed at riskparticularly neo-Jeffersonian, Jacksonian workers threatened by the possibility of becoming what Karl Marx called the inanimate limbs of urban industry.31 Santa Annas leg gained an exhibitionary value different than that of Palmers prosthesis, requiring a different cultural institution for its display. Whereas Palmers leg was on display at trade exhibitions, Santa Annas leg was immediately presented at, and figured in terms of, museums. Even the soldiers discussing Santa Annas leg invariably accorded it an exhibitionary value. One balladeer ventriloquizes Santa Annas imagined lament in these terms: For in the museum I will see / The leg I left behind me.32 George Furber, a volunteer soldier, similarly figures one of Santa Annas deserted homes as a museum, writing of his perambulations through its galleries: In the long gallery, we smiled as we observed one of the generals artificial legs lying there, booted finely, and excellently manufactured.33 Commenting on the enterprising spirit that created a virtual cottage industry around Santa Anna, a British soldier in the service of the United States records how several enterprising Yankees . . . for some months after [the battle] continued to exhibit veritable wooden legs of Santa Anna through the towns and cities of the States, with great success, making a pretty considerable speculation of it.34 Although the soldier intends veritable wooden legs as an ironic commentary on the forgeries of the prosthetic that circulated as authentic, this seeming paradox underscores the fact that Santa Annas leg gained a metaphorical value indifferent to the literal and particular legs that acted as bearers of that value (as Marx will say of the materiality of commodities). These real and imagined exhibitions of the legas we will see even more clearly with Barnumspectacularly demonstrated the regenerative benefits that U.S. imperialism offered Jacksonian workers. Rhetorically, labor under capitalism fragments the body of the worker to the extent that it can be primarily figured through the abusive synecdoche of hands.35 The leg of Santa Anna offered an imperial pros-

36American Literature

thesis through which U.S. workers could be restored to a full, and ethnically reconciled, republican body. George Strattons play The Siege of Mexico; or, the Confrere of Mechanics (1850), for instance, dramatically links ethnic reconciliation, the regeneration of artisanal autonomy, and the museum-like exhibition of Mexico. The plays protagonist is Hans, a German American bootmaker who lives in Mexico during the war. Juxtaposing the cramped confines of the northeastern United States to the expansiveness of Mexico, Hans declares: [Y]ou would hardly believe that the humble abode of a New Eng land mechanic and factory girl is a part of the once spacious palace of the magnificent Montezuma the Second. His new home is so spacious that he intends to transform it into a museum, telling a Catholic monk that he mean[s], at some future day, to open this remnant of Montezumas Palace as a museum and that he want[s] [the monk] for one of its curiosities.36 Indeed, the joking exhibition of individuals is a staple of Melvilles Yankee Doodle articles, in which he routinely proposes that Barnum exhibit Generals Taylor and Santa Anna.37 Since the play was published in 1850, it is likely that the playwright had Barnums museum display of Santa Annas leg in mind. Imagining the conquered territory as a museum, the artisan Hans exhibits an image of Mexico as a nonconstricting space where workers could work honestly, autonomously, and for themselves.

Yankee Doodle and the American Museum

Santa Anna and the U.S. soldiers he battled were united in this: they both made speculations on the generals leg, subjecting it to multiple figurative operations. As we have seen, U.S. observers judged inappropriate Santa Annas transformation of his literal loss into a symbolic surplus. This surplus of sovereignty had the effect of rendering commensurate the generals severed leg and the fully dead, hauntingly suggesting that the Mexican nation itself functioned as Santa Annas figurative prosthetic. Examining the prosthetic limbs display in the American Museum, Melville transposes this critique, claiming that U.S. proimperialists themselves gained an improper symbolic surplus from the leg, a surplus they put to work to secure working-class consent to imperial war. In a letter to his brother Gansevoort, Melvilles ironic but anxiety-laden account of the outbreak of the war focuses on the figurative means deployed to produce the wars cross-class appeal:

Ahab, Santa Anna, and Moby-Dick37

People here are all in a state of delirium about the Mexican War. A military arder pervades all ranksMilitia Colonels wax red in their coat facingsand prentice boys are running off to the wars by scores.Nothing is talked of but the Halls of the Montezumas. And to hear folks prate about those purely figurative apartments one would suppose that they were another Versailles where our democratic rabble meant to make a night of it ere long.38 Melville understood popular support for imperialism as a state of delirium marked by intense affects and swift unreflective action. Three years later, in Mardi (1849), he linked lapses in self-consciousness to popular support for imperial war: And though unlike King Bello of Dominora, your great chieftain, sovereign-kings! may not declare war of himself; nevertheless, has he done a still more imperial thing: gone to war without declaring intentions. You yourselves were precipitated upon a neighboring nation, ere you knew your spears were in your hands.39 More acted upon than acting, the populace wars in the passive voice, unconsciously giving popular legitimacy to the illegal acts of a thinly veiled President Polk. This passivity also surprises Ishmael and the crew of the Pequod, who marvel[ ] how it was that they themselves became so excited by Ahabs performance ( MD, 175). Melville, like Ishmael, is attuned to if not admiring of the immense potential of this democratic rabble, figuring their revolutionary power through an allusion to Versailles. Yet this frantic democracy is articulated with delirious imperialism ( MD, 164). Melvilles letter poses important questions: Why did the democratic rabble subordinate its power to, and articulate its desires with, elite imperialism; and what representational strategies produced, inflated, and managed this delirious desire for empire? What indeed is the relationship between the purely figurative apartments of the Halls of the Montezumas and the military ardor pervad[ing] all ranks? The figurative, and figuring, apartments of Barnums American Museum offer some answers. Harrison has argued that museums were critical locations for the staging of disputes between high and low culture during the 1840s.40 The geographical location of Barnums museum maps the cultural antagonisms the museum had to negotiate.41 Caught between high and low, the Bowery Bhoys and the New York middle class, Barnum attempted to obliterate the social fault lines crisscrossing his museum so that it would appeal to middleclass audiences as well as members of the upward-identifying work-

38American Literature

ing class.42 The museum had a conduct code of behavior in order to ensure middle-class decorum, and Barnum had plain-clothes detectives in the crowds to ferret out improper behavior and, of course, prostitutes.43 Thus, even while much of the content of the museum was for working-class audiences, the performances the museum demanded were in keeping with middle-class norms.44 These norms frequently registered in terms of a national identity that sutured over the fault lines of class. The American Museum was arrayed with a set of flags, patriotic slogans, and so on; much later, one could purchase timbers from Abraham Lincolns cabin in the gift shop.45 Barnums museum articulated this urban nationalism with U.S. imperialism, illustrating Shelley Streebys observation that there were multiple connections between city and empire.46 More specifically, U.S. national culture and working-class urban culture in particularof the later 1840s was structured through U.S. imperialism in Mexico. Thus, the position of Barnums museum within New York needs to be read vis--vis its position within an imperial geography, in which New York was linked to the Southwest and Mexico through the circulation of sensational narratives and displays. The circulation of Santa Annas leg spectacularly articulates New York cultural antagonisms with imperial territorialism in Mexico. Barnums exhibition of the limb began on 26 June 1847. Even though some claimed that the prosthesis on display was a fake, the minimal cost of admission (twenty-five cents) assured the false limb a large audience of upward-identifying patriots drawn from the urban working class.47 The limb itself, however, was not the only thing attendees would have consumed. It is likely that much of the history of appropriation I have just traced would have been incorporated into Barnums exhibition.48 Neil Harris describes Barnums representational practices: The objects inside the museum, and Barnums activities outside, focused attention on their own structures and operations, were empirically testable, and enabledor at least invitedaudiences and participants to learn how they worked. They appealed because they exposed their processes of action. . . . [O]ne might term this an operational aesthetic, an approach to experience that equated beauty with information and technique.49 Barnums things were never Starbuckian dumb things whose simple materiality provided sensational stuff for visual consumption. Rather,

Ahab, Santa Anna, and Moby-Dick39

to get the full experience of Barnums museum, audiences had to engage with the objects, to seek information about Barnums mode of displaying the thing as well as about the thing itself. Bluford Adams has argued for the centrality of narrative to Barnums operational aesthetic, claiming that Barnums stories were far more important than the objects they supposedly contextualized. As he describes it, narratives of acquisition emphasized where [the object] had come from, how it had arrived, and how much it had cost.50 Barnums things functioned as an occasion for the story that was told about them; an object crystallized a web of social relations and thingly histories from which its full meaning came. Regarding Santa Annas prosthesis, audiences would have been encouraged to participate in the imperial appropriation of the limb (and the land) by imaginatively and narratively reenacting its history of acquisition. This material and narrative appropriation of imperialism by Barnums working-class audience assisted in the formation of free-labor republican militarism, providing a kind of resolution for the class antagonisms that threatened to consume urban centers of the Northeast. Melville recognized the powerful cross-class appeal of imperial war, as well as the way empire was being deployed as a tool for managing the demands posed by free-laborists and radicals in the Northeast. Implicit in his description of the cultural atmosphere of New York is a critique of imperial representational modalities that presented Mexico as a land of riches waiting to be snatched at little cost. As we have seen, the purely figurative apartments were continually presented to U.S. workers as having material, factual existence through sensational literature and exhibitions. In Yankee Doodle, Melville claims that these figures have no literal referentthat they are, in short, humbug. Melvilles article on Santa Annas leg deflates, by satirically inflating, the symbolic value of the imperial trophy: yankee doodle has come to one conclusion. If the whole world of animated naturehuman or bruteat any time produces a monstrosity or a wonder, she has but one object in viewto benefit barnum. barnum, under the happy influence of a tallow candle in some corner or other of Yankee land, was born sole heir to all her lean men, fat women, dwarfs, two-headed cows, amphibious sea-maidens, large-eyed owls, small-eyed mice, rabbit-eating anacondas, bugs, monkies and mummies. His domain extends even to

40American Literature

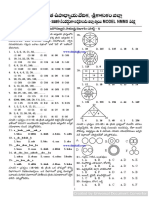

the forest, and he claims exclusive right to all wooden legs lost, as estrays on the field of battle, and, as a matter of course, to the boots in which they are encased. We give an interior view of the Barnum Property, embracing a life-sized exhibition of the great Santa-Anna Boot, which has been brought onby the loops of two able-bodied young negroesdirect from the seat of war.51 The joking tone of the article turns critical when Barnum is figured less as the heir to the weird than as an appropriator of loss: His domain extends even to the forest, and he claims exclusive right to all wooden legs lost, as strays on the field of battle (italics added). Barnums domain gives him a sovereign right to appropriate loss, to spectacularize it and to speculate on it, as if remnants of others losses were his rightful and exclusive property. Melville repeats with a slight difference the very critique U.S. commentators made of Santa Annas memorial of his lost limb: Barnum speculates with (anothers) loss, improperly appropriating surplus capital from (anothers) bodily disappropriation. Barnums appropriation of profit from loss is mirrored in the way the leg itself loses its literal referent and gains a metaphorical surplus. Melville satirically marks the boots metaphoric and affective inflation by literally inflating its size. It was carried by two ablebodied young negroes direct from the seat of war and advertised as one thousand tines biger than any other mans leg (see fig. 1). The metaphorical inflation of the leg inversely corresponds to the decrease in price to view it, for Melville claims that Yankee Doodles description of the object giv[es] for a sixpence what [Barnum] would have charged a quarter for.52 The leg enlarges as its potential working-class audience grows; the imperial signifier inflates as a function of working-class imperial desire. The class-leveling, democratic space of the museum precipitates (as in Mardi ) a frantic democracy, whose excited rush to view the boot seems to further inflate its size. The gigantic leg functions as a synecdoche of the museum, but it also threatens to incorporate and contain the entire space. In a process Jacques Derrida calls invagination, the part threatens to make the whole a part of itself.53 The American Museum (the boot itself covers over the word American) risks being subsumed under a Mexican prosthesis; the United States risks being subsumed by the purely figurative apartments of Mexico. The prosthesis of empire might take over the full body of the nation.

Figure 1View of the Barnum Property, woodcut from Yankee Doodle, 31 July 1837.

42American Literature

Melvilles critique of Barnums display of the prosthesis does double duty as a critique of imperial discourses on regeneration and reparation. While the war in elite terms was represented as a means of securing indemnity for lost property, in popular terms the justification for war was represented through dismembered, violated bodies. The figure of the raped woman was central to this imaginary, but so too were the wounded bodies of U.S. men on the southwestern frontier.54 These bodies demanded a response; as Congressman Hugh Haralson declared, Blood cries aloud upon us for . . . action.55 For Senator Lewis Cass, the necessity of avenging wounded bodies and of preventing such atrocities from happening again required a full military invasion.56 Securing the wholeness of American bodies necessitated geographic expansion, and working-class proimperialists promoted this logic. Not only would war provide imaginary reparation to the wounded and dead, but the material form of reparationterritory offered what Frederick Jackson Turner would call perennial rebirth to the northeastern proletariat suffering in the manufacturing cities.57 George Lippards epigraph for his Legends of Mexico (1847)Thomas Paines charge that [w]e fight not to enslave, nor for conquest / But to make room upon the earth for honest men to live inexpresses neatly the link between imperial war, territory, and proletarian regeneration.58 Ahabs demand for vengeance thematizes this critique. Yankee Doodles analysis suggests that imperial war was not offering a whole, regenerated body to U.S. workers. Rather, in their enthusiastic consumption of the metaphor of imperial gain, the working class simply exchanges synecdoches: who once were hands have now become legs. The monstrous size of Santa Annas leg, bigger than all the bodies rushing beneath it, suggests that if urban workers are being reincorporated and regenerated, this reincorporation still leaves these workers as mere parts of a body. The very symbolics that secure their enthusiasm and gain their consent leave the democratic rabble subordinated within a national design. Melville, I propose, is alerting us to the social logic of hegemony formation, in which a single part of a social body gains an inflated and representational status that subordinates all other parts of the social body. It is this logic that Moby-Dick scrutinizes when Ahab convenes his crew on the quarterdeck of the Pequod, securing their consent to dismember his dismemberer.

Ahab, Santa Anna, and Moby-Dick43 Barnum on Board

It is tempting to read Ahab as Santa Anna, given the similarity of the figurative operations to which they subject their lossnot to mention the more obvious trait they share. Yet Melvilles relationship to the general was mediated through Barnums exhibit, and it is Barnums representational practices, and their class effects, that Melville explores in Moby-Dick. In an article documenting Melvilles critique of Jacksonianism and free-labor ideology, Ian McGuire argues that the novel is interested in examining the reasons for [free-labor republicanisms] failure as an economic and political doctrine.59 Free-labor republicanism did not simply fail, however; it became imperial. Melville is interested in how territorial imperialism came to be accepted as an alternative to the industrial capitalist order that free-labor republicans resisted, arguing in his Yankee Doodle article that deliteralized and metaphorized things enabled workers to imagine empire as a regenerative program. In the relations between Ahab and his crew, as between Barnum and his audience, Melville isolates two figurative operations through which imperial things were imbued with affect and meaning: synecdoche, through which a single part of a whole comes to stand in for the whole; and metaphor, in which a figure gains an unstable, nonliteral referent that inflates its signifying capacity. Ahabs loss stands in for the grievances of his crew in general, and thenas we can see through the reparation Ahab demands, the sublime Thing of the white whalethis loss is inflated to metaphysical dimensions. It is through these figurative operations that Ahabs crew willfully turns from whaling to revengeor, from industry to empire. Read from the perspective of Santa Annas prosthesis and the cultural history it indexes, Moby-Dick decomposes the logic through which working-class resistance to industrial capitalism produced an imperialist hegemonic bloc.60 Industrial capitalism, Moby-Dick suggests, exposes subjects to heteronomous violence, disaggregating social collectivities and individual bodies. Ahab, of course, loses his limb on a whaling voyage, Pip goes mad, and [t]oes are scarce among veteran blubber-room men ( MD, 458). In the chapter A Squeeze of the Hand, Ishmael marks how capitalism splits subjects, synecdochalizing them into a community of hands. His enthusiasm stands in marked contrast to Jacksonian fears about the loss of autonomy; for Ishmael, the workers

44American Literature

disembodied but mingling parts open a new form of collectivity, one that does not call for bodily regeneration or social reincorporation. This possibility, however, is foreclosed, and Ishmael maintains that if capitalism unites dispersed subjects, it maintains them in a disaggregated dispersal. Commenting on the cosmopolitan crew, he turns their island provenance into a metaphor for a dispersed social being: They were nearly all Islanders in the Pequod, Isolatoes too, I call such, not acknowledging the common continent of men, but each Isolato living on a separate continent of his own ( MD, 131). Ishmael notes that even when capitalism brings disparate subjects from all over the world into the enclosed space of a ship, it lacks the figurative resources to articulate these isolated continents: the only metaphorics available to capitalism are those that point to a sociality of estranged dispersal. Marxs Eighteenth Brumaire (published a year after Moby-Dick1852and in New York as well) famously attends to this dispersal-in-unity: [T] he great mass of the French nation is formed by the simple addition of isomorphous magnitudes, much as potatoes in a sack form a sack of potatoes. Moby-Dick comes to much the same conclusion as Marx: They cannot represent themselves; they must be represented.61 If Rogin argues that only Ahabs allegory gives Moby-Dick its narrative, it is because Ahabs quest gives the Pequod the social cohesion that capitalism lacks (SG, 116). Ishmael figures this cohered society as a republican collectivity federated through grief: Yet now, federated along one keel, what a set these Isolatoes were! An Anacharsis Clootz deputation from all the isles of the sea, and all the ends of the earth, accompanying Old Ahab in the Pequod to lay the worlds grievances before that bar from which not very many of them ever come back ( MD, 132). Ahab federates this community of shared grief through the careful staging of his lost leg; his particular loss stands in for and represents the grievances of the whole crew. Ahab, in other words, offers his loss as a synecdoche for the crews grief, a social-symbolic action best described by theorists of hegemony. The concept of hegemony describes the ways in which nonidentical classes (with, therefore, nonidentical interests) join together in a makeshift unity. Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe write that in a hegemonic articulation of society, a set of particularities establish relations of equivalence between themselves. It becomes necessary, however, to represent the totality of the chain, beyond the mere differential particularisms of

Ahab, Santa Anna, and Moby-Dick45

the equivalential links. What are the means of representation? As we argue, only one particularity whose body is split, for without ceasing to be its own particularity, it transforms its body in the representation of a universality transcending it . . . .62 For a set of particularities (like Ishmaels set of Isolatoes) to form a politically cohesive unit, one particularity within this articulated network needs to serve as a synecdoche, as a part functioning to represent the whole chain of equivalencies as if universal. With his literally split body, Ahab performs this hegemonic articulation, transforming his lost leg and his visible prosthesis into a synecdochal object capable of mediating between his own particular injury and the general grievances of the crew. The hegemonic signifier has the phallic function of providing symbolic consistency to the social field. As Laclau and Mouffe put it, Jacques Lacans master-signifier involves the notion of a particular element assuming a universal structuring function within a certain discursive field . . . . At the same time, [W]hatever organization that field has is only the result of that function . . . .63 Hegemony formation is a poetic act in which hegemonic signifiers assume the position of the phallus and re-form social-symbolic relations. Ahab, Rogin suggests, imposes allegorical control and determinate meaning: hegemonic signifiers impose this meaning by articulating disarticulated particularities within a unifying narrative (SG, 111). In line with this reading, Leslie Katz has called attention to the image-making power of the amputees state in Moby-Dick.64 In The Quarter-deck, Ahab federates the crew by deploying many of the rhetorical, representational, and performative techniques common to U.S. working-class cultureparticularly those deployed by Barnum. Like Barnum, Ahab offers a narrative that enables his crew to imaginatively appropriate and consume the history by which he acquired his object. Ahabs narrative, however, is not one of simple acquisition; it is also one of bodily dispossession. The crew comes to appropriate Ahabs loss as if it were its own. Ishmael recounts: I, Ishmael, was one of that crew; my shouts had gone up with the rest; my oath had been welded with theirs . . . . A wild, mystical, sympathetical feeling was in me; Ahabs quenchless feud seemed mine. With greedy ears I learned the history of that murderous monster against whom I and all the others had taken our oaths of violence and revenge ( MD, 194; italics added). Ahabs staging of his loss, and the crews identifi-

46American Literature

cation with it, creates a pseudo-democratic community and space in which captain and crew intimately mingle. Whereas in White-Jacket (1850) the disciplinary performances on the quarterdeck reproduce divisions between officers and crew, in Moby-Dick the quarterdeck is a space in which the ships social divisions are suspended and a carnivalesque atmosphere reigns. Due to this suspension of social divisionsa suspension that recalls the class politics of Barnums American MuseumHarrison claims that the Pequod contains a meliorative potential lost to the New York cultural landscape it metonymizes.65 The heterotopic space of the ship allows for the obliteration of cultural antagonisms between high and low, workers and elites. But reading Ahabs performance aboard the ship as a repetition of Barnums display of Santa Annas leg complicates this claim: the quarterdeck of the Pequod metonymizes a New York cultural landscape structured by the U.S.-Mexican War. Like Melvilles Barnum, Ahab makes a domain of loss. And this domains founding carnival is one of empire. The scenes cross-class social hybridity is reinforced and expressed by a carnivalesque generic mixing that brings together theatrical stage directions, soliloquies, novelistic narration, a shanty, ritual call-and-response forms, philosophical digression, and so on. If the quarterdeck briefly resembles a democratic state, it is also a state of delirium, a frantic democracy. Ahab instrumentalizes these delirium-inducing moments of heteroglossic cultural democracy to attain his hegemonic position. Like the thinly veiled Polk of Mardi, Ahab possesses a precipitating manner that results in the crew picking up their harpoons to kill the whale without knowing why ( MD, 505). Ahabs call-and-response leaves the mariners marvelling how it was that they themselves became so excited at such seemingly purposeless questions (175). Ahab even appears to draw on workingclass literary culture. Like a figure out of a dime novel, Neil Tolchin points out, Ahab rants and raves on the quarterdeck.66 Indeed, Ahabs ritualization of revenge, as well as the affective intensity of his performance, recalls the theatrical quality of vengeance in both Lippards Bel of Prairie Eden (1848) and Ned Bluntlines Magdalena (1847). The captain exclaims: [I]t was Moby Dick that dismasted me; Moby Dick that brought me to this dead stump I stand on now. Aye, aye, he shouted with a terrific, loud, animal sob, like that of a heart-stricken moose; Aye, aye! it was that accursed white whale that razeed me; made a poor pegging lubber of me for ever and a day! ( MD, 177).

Ahab, Santa Anna, and Moby-Dick47

This intensity thrills the crew. When Ahab declares their shifted purpose (And this is what ye have shipped for, men!), the crew mirrors their increasing proximity to Ahabs psycho-affective state by literally moving closer to Ahab as they express their assent to his mission: Aye, aye! shouted the harpooneers and seamen, running closer to the excited old man. Ahab even ritualizes the genre of the contract: What say ye, men, will ye splice hands on it, now? ( MD, 177). As Ishmael makes clear, however, this splicing of hands did not appear to the crew as an ordinary capitalist contractthe kinds of contracts Jacksonian workers feared would make them wage slavesbut as an oath. Unlike the A Squeeze of the Hand chapter, in which bodiless hands squeeze! squeeze! squeeze! in an ecstatic refusal of reincorporation, captain and crew incorporate themselves in order to effect a symbolic reembodiment. Ahabs synecdochalization of his loss recodes the social-symbolic field of the Pequod, recasting the capitalist value and object relations that structured the social life of the ship and offering the crew an alternative to contracts and capitalism. When Ishmael signs his contract to ship on the Pequod, Bildad and Peleg subject him to a humiliating evaluation and devaluation of his skills, dictating and diminishing the value of his labor ( MD, 8587). Ahabs oath, with its intimate, voluntarist, and masculine splicing of hands, stands in marked contrast to the contracts of capitalism. The doubloon that Ahab posts as a reward simulates the splicing as a moment of contract formation; at the same time, it marks Ahabs ability to determine and declare a new modality of value relations. The doubloon is less an object with which one would purchase goods on land (worth sixteen dollars, about double an unskilled whalers monthly wage), and more a signifier of incorporation into the new economy of things that Ahab founds.67 Ahabs lost leg can serve as a synecdoche for the crews grief because of the metaphoric value with which he inflates it. His ivory is less a prosthesis than a grim insistence on the irreparable nature of his loss. The carpenter compares Ahabs prosthesis to those available in urban marketplaces: Time, time; if I but only had the time, I could turn him out as neat a leg now as ever (sneezes) scraped to a lady in a parlor. Those buckskin legs and calves of legs Ive seen in shop windows wouldnt compare at all. They soak water, they do; and of course get rheumatic,

48American Literature

and have to be doctored (sneezes) with washes and lotions, just like live legs. ( MD, 511) The carpenter suggests that these nearly living prostheses are nearly literal substitutions for lost limbs. Yet Ahab refuses to take his loss literally, rejecting commensurate substitution and the regenerative possibility of capitalist exchange. This becomes clearest on the quarterdeck, when he smites his chest and declares to Starbuck, Nantucket market! . . . If moneys to be the measurer, man, and the accountants have computed their great counting-house the globe, by girdling it with guineas, one to every three parts of an inch; then, let me tell thee, that my vengeance will fetch a great premium here! ( MD, 178). Where capitalist market relations work through the substitutability of objects for money, Ahab posits an alternative mode of valuing objects, here marked by the term vengeance. Vengeance establishes a personal regime of values that governs the substitutability of things, relating incommensurables in an aneconomic way. Ahabs desire for regeneration through violence exceeds the economy of substitution; he intends to generate a surplus from his dismasting. Insofar as the captain desires access to that unknown but still reasoning thing standing behind the phenomenal world, Ahabs bodily loss is converted into a metaphysical gainthe Ding an sich for his missing leg ( MD, 178). Ahab deliteralizes and metaphorizes his loss: a lost leg becomes a white whale. His generation of symbolic surplus from literal loss recalls Santa Anna, who turned his amputation into political capital; Barnum, who turned Santa Annas prosthetic limb into profit; and the working-class audience of the Yankee Doodle sketch, whose enthusiasm for Barnums exhibit seems to increase the physical size of the prosthesis itself. More generally, Ahabs inflationary logic mirrors the logic of claims made by proponents of the war on Mexico. Polk might not have demanded access to a noumenal Thing, but he definitely wanted more than the United States claimed to have lost. The anonymous author of The Conquest of Mexico! (1846), for instance, cites Polks identification of a series of unredressed injuries inflicted by the Mexican authorities and people on the persons and property of citizens of the United States, and provides an index that details the exact monetary amount of damages done.68 As Mexico was fiscally bankrupt, however, the United States would have difficulty recovering the actual value of losses. The author then abjures the logic of finan-

Ahab, Santa Anna, and Moby-Dick49

cial substitution, claiming that only conquest would provide commensurate reparation: [T]here is no mode of [indemnification] but that of invasion and conquest. The Mexican republic is politically, socially, and morally dissolute. . . . It is financially exhausted, and if we would obtain indemnity at all, it must be in its territory. Yet The Conquest of Mexico! admits that redress is a providential pretext, that its calculus of loss is a fiction for gain: In retribution for [Mexicos] corruptions, divine providence has allowed it to create an unavoidable necessity for invasion.69 The United States would obtain so great an indemnity that it would, in turn, pay Mexico.70 As Rogin points out, pacifists like Theodore Parker compared the imperial United States to the biblical Ahab, who cites a fictive injury as a pretext for killing Naboth and claiming his coveted vineyard (SG, 123). Narratives of loss grounded imperialisms economy of regeneration. Starbucks failed reinscription of capitalist substitution is an attempt to get out of this blasphemous economy of inflationary reparation. James Duban reads Starbucks feckless attempt to reinscribe capitalist value relations as an allegory for the failure of Whigs to provide strong opposition to the declaration of war.71 It also marks the failure of economistic argumentslike those deployed by activists in New Eng landto ground a socially thick, antiwar movement.72 Like Barnums great Santa Anna boot, the mad captain provides a metaphor of loss and gain capacious enough to provide a figurative apartment for the crew. However, if Ahab offers his loss as a representative and inflated metaphor, the crew maintains its significance. The irony of hegemony formation, as Melville suggests in his Yankee Doodle sketch, is that the sign that subordinates a class to the hegemon in fact only gains its signifying power though the desire of the subordinated class. Just as the working-class audience maintained and inflated the signifying capacity of Santa Annas boot, so too does the crew maintain the sign of Ahabs leg. In the chapter Ahabs Leg, we are told that Ahab has had an accident: [H]is ivory limb having been so violently displaced, that it had stake-wise smitten, and all but pierced his groin; nor was it without extreme difficulty that the agonizing wound was entirely cured ( MD, 505). Significantly, this wound is a secret, and the reader discovers why it was, that for a certain period, both before and after the sailing of the Pequod, he had hidden himself away with such Grand-Lama-like exclusiveness. During this period, Ishmael wanted nothing more than to [c]lap eye on

50American Literature

Captain Ahab. In The Prophet, Ishmael, riveted by Elijahs story, receives an ambiguous, half-hinting, half-revealing, shrouded sort of talk that produces in him all kinds of vague wonderments and halfapprehensions, and all connected with the Pequod; and Captain Ahab; and the leg he had lost . . . . Ahabs lack of his sensational thing, his invisibility, and the rumor that swirls around him, make his appearance on the quarterdeck that much more affectively intense. He only emerges into visibility once the carpenter hasin secretprovided him with his sensational prosthesis. Well, manmaker! Ahab calls out to him ( MD, 506, 80, 103, 512). Manmaker indeed: the crew literally produces the representational means of its own hegemonic subordination. Ahab exposes the crews subordination as the novel reaches its conclusion, effectively dismissing Ishmaels republican figure of the Anacharsis Clootz deputation, federated along one keel ( MD, 132). In his reading of Barnums exhibition, Melville undercuts the Mexican Wars rhetoric of bodily regeneration and reparation by depicting the incorporation of the working class into national culture as a displacement of synecdoches: laboring hands became legs. This critique becomes explicit in Moby-Dick. Ahab, claiming a metaphoric existence beyond his literal body, promotes a radical individualism akin to that offered by the frontier: Ye see an old man cut down to the stump; leaning on a shivered lance; propped up on a lonely foot. Tis Ahab his bodys part; but Ahabs souls a centipede, that moves upon a hundred legs ( MD, 611). Even after losing his second prosthetic limb, Ahab claims, In his own proper and inaccessible being . . . . Ahab is for ever Ahab, man. He locates himself beyond any kind of embodiment, prosthetic or fleshy: [E]ven with a broken bone, old Ahab is untouched; and I account no living bone of mine one jot more me, than this dead one thats lost ( MD, 610). Ahabs refusal of the mutual, joint-stock world in the name of self-making is, however, revealed to be a ruse; he is still in a state of inter-indebtedness, but as the hegemon is to the hegemonized ( MD, 68, 514). In the culminating scenes, Ahab reveals that his centipede soul is composed of the bodies of his men: Ye are not other men, but my arms and my legs ( MD, 619). Empire, Melville proposes, offers no regeneration for the violation of living a synecdochalized life. There is no exit from the figurative, Moby-Dick suggests. Starbucks attempt to mute the social garrulousness of objectsto show things to

Ahab, Santa Anna, and Moby-Dick51

power, as it werehas all the political efficaciousness of pointing out that Santa Annas prosthesis was just leather, cork, and wood. To take Santa Annas leg literally, or to decide that Moby-Dick is just a whale, is an impossible taskno one else took it so. Yet, as Melville intimates, it is not the literalness of things but the contextually situated way they are figured that makes them socially and politically generative, and that renders the social legible. Moby-Dick rigorously dissects the figurative operations through which U.S. proimperialists transformed Santa Annas leg into an imperial prosthesis, a metaphor of the regenerative autonomy that Mexico offered to the New York working class. Read with the history of Santa Annas leg, the textual context, status, and aims of the novel dramatically shift. Insistently calling attention to the political effects of the figurative, Melville offers a hermeneutic for readingand critiquingthe social grammar of collectivity formation. Moby-Dick is less an allegory of the American 1848 than an analysis, one that offers a rhetorical theory of the political history that Santa Annas prosthesis metonymically insinuates into the text.

University of Pennsylvania Notes I would like to thank Amy Kaplan, David Kazanjian, Murad Idris, Ania Loomba, Phil Maciak, and Ashley Cohen for their insightful comments on this essay. 1 See Jesse Alemn, The Ethnic in the Canon; or, On Finding Santa Annas Wooden Leg, MELUS 29 (fall-winter 2004): 16582. 2 Herman Melville, View of the Barnum Property, Yankee Doodle, 12 March 1870; reprinted in The Piazza Tales and Other Prose Pieces, 1839 1860, vol. 9 of The Writings of Herman Melville, ed. Harrison Hayford, Alma A. MacDougall, and G. Thomas Tan selle (Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern Univ. Press and the Newberry Library, 1987), 448. 3 Herman Melville, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (1851; reprint, New York: Penguin Classics, 2003), 78. Further references to Moby-Dick are to this edition and will be cited parenthetically in the text as MD. See Les Harrison, The Temple and the Forum: The American Museum and Cultural Authority in Hawthorne, Melville, Stowe, and Whitman (Tuscaloosa: Univ. of Alabama Press, 2007), 98105. 4 Elaine Freedgood, The Ideas in Things: Fugitive Meaning in the Victorian Novel (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2006), 11. 5 My thanks to Jos Lavery for this point. 6 Freedgood, The Ideas in Things, 12. 7 Freedgood explains, [A]n object in a novel, in order for it to have mean-

52American Literature

10

11

12

13 14

ing, cannot be itself, even in a two-dimensional, scenery producing kind of way; it is wrenched away from that possibility by the metaphorical relation itself. . . . Objects become metaphorical (and meaningful) through a loss of many of their specific qualities. They retain only those that illuminate something about the predicate to which they must yield (The Ideas in Things, 10). My understanding of loss as productive is inspired by David L. Eng and David Kazanjian, who write that loss is not a purely negative quality but is rather laden with creative, political potential (Eng and Kazanjian, eds., preface to Loss: The Politics of Mourning [Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press, 2003], ix). Herman Melville, Correspondence, vol. 14 of The Writings of Herman Melville, ed. Lynn Horth (Evanston and Chicago: Northwestern Univ. Press and the Newberry Library, 1993), 40. Michael Paul Rogin, Subversive Genealogy: The Politics and Art of Herman Melville (Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press, 1985), 108. Further references are to this edition and will be cited parenthetically in the text as SG. See David Chappell, Ahabs Boat: Non-European Seamen in Western Ships of Exploration and Commerce, in Sea Changes: Historicizing the Ocean, ed. Bernhard Klein and Gesa Mackenthun (New York: Routledge, 2004), 7589; Rodrigo Lazo, So Spanishly Poetic: Moby-Dicks Doubloon and Latin America, in Ungraspable Phantom: Essays on MobyDick, ed. John Bryant, Mary K. Bercaw Edwards, and Timothy Marr (Kent, Ohio: Kent State Univ. Press, 2006), 22437; Ikuno Saiki, Strike though the Unreasoning Masks: Moby-Dick and Japan, in Whole Oceans Away: Melville and the Pacific, ed. Jill Barnum, Wyn Kelley, and Christopher Sten (Kent, Ohio: Kent State Univ. Press, 2007), 18398; Elizabeth Schultz, The Subordinate Phantoms: Melvilles Conflicted Response to Asia in Moby-Dick, in Whole Oceans Away, ed. Barnum, Kelley, and Sten, 199212; Erik Rangno, Melvilles Japan and the Marketplace Religion of Terror, Nineteenth-Century Literature 62 (March 2008): 46592; and Antonio Barrenecha, Conquistadors, Monsters, and Maps: MobyDick in a New World Context, Comparative American Studies 7 (March 2009): 1833. See Alexander Saxton, The Rise and Fall of the White Republic: Class Politics and Mass Culture in Nineteenth-Century America (London: Verso, 1990); and Sean Wilentz, Chants Democratic: New York and the Rise of the American Working Class, 17881850 (New York: Oxford Univ. Press, 1986). See David R. Roediger, The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class (London: Verso, 1991). See Bill Brown, Science Fiction, the Worlds Fair, and the Prosthetics of Empire, 19101915, in Cultures of United States Imperialism, ed. Amy

Ahab, Santa Anna, and Moby-Dick53 Kaplan and Donald E. Pease (Durham, N.C.: Duke Univ. Press, 1993), 12963. The classic text on the trope of regeneration is Richard Slotkin, Regeneration through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 16001860 (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan Univ. Press, 1973). See Robert L. Scheina, Latin Americas Wars: The Age of the Caudillo, 17911899 (London: Brassey, 2003), 169. See Alemn, Ethnic in the Canon, 168. Frances Erskine Caldern de la Barca, Life in Mexico, 2 vols. (Boston: Little, Brown, 1843), 2:29091. See, for instance, George Frederick Augustus Ruxton, Adventures in Mexico and The Rocky Mountains (New York: Harper and Brothers, 1848), 29; and Albert M. Gilliam, Travels over the Table Lands and Cordilleras of Mexico (Philadelphia: John Moore, 1846), 4155, 120. The tale entered into childrens schoolbooks, presumably to liven up accounts of the Mexican War; see Charles Augustus Goodrich, A History of the United States of America, Adapted to the Capacity of Youth (Boston: Brewer and Tileston, 1852), 302. See also the gift book The Rough and Ready Annual; or, Military Souvenir (New York: Appleton, 1848); as well as George Denison Prentice, Prenticeana; or, Wit and Humor in Paragraphs (1859; reprint, Philadelphia: Claxton, 1871), 14244, 180. For a discussion of Prescott and U.S. historiographys supplementation of its past with a primitive romanticism drawn from Mexico, see Alemn, Ethnic in the Canon, 167. Gilliam, Travels over the Table Lands, 11920. Ibid., 120. See also Marcius Willsons account of the overthrow of Santa Anna, in which symbolic violence is visited upon the leg: Rejoicings and festivities of the people followed. The tragedy of Brutus, or Romance made Free, was performed at the theatre in honor of the success of the revolutionists; and every thing bearing the name of Santa Anna,his trophies, statues, portraits, were destroyed by the populace. Even his amputated leg, which had been embalmed and buried with military honors, was disinterred, dragged through the streets, and broken to pieces, with every mark of indignity and contempt ( American History: Comprising Historical Sketches of the Indian Tribes (New York: Mark H. Newman, 1847), 614. George Wilkins Kendall, Narrative of the Texan Santa F Expedition (London: Henry Washbourne, 1847), 203. See Alemn, Ethnic in the Canon, 168. Maximilian Joseph Chelius, A System of Surgery, trans. John South (London: Henry Renshaw, 1847), 846. See The Sixth Exhibition of the Massachusetts Charitable Mechanic Association (Boston: Eastburns Press, 1850), 16667; and Albert Gallatin Browne, Reports of the First Exhibition of the Salem Charitable Mechanic Association (Salem, Mass.: Streeter and Porter, 1849), 43.

15 16 17 18

19

20

21 22

23 24 25 26

54American Literature

27 Redwood Fisher, Fishers National Magazine and Industrial Record 3 ( July 1846): 155. 28 William Hamilton, Journal of the Franklin Institute 19 ( January 1850): 61. 29 The reviewers note, It is for the benefit of those who have had the misfortune to lose a leg, not less than for the encouragement of the inventor and the manufacturers, who are deserving of their patronage, and who we regard as their greatest benefactors, that we [doctors endorse Palmers leg] ( Jefferson Church, Jas M. Smith, N. Adams, Alfred Lambert, Edwin Seeger, R. G. W. Eng lish, and O. C. Chaffee), New Eng land Botanic, Medical, and Surgical Journal, 1 September 1849, 279. 30 See Ezra M. Prince, Transactions of the McLean County Historical Society 1 (Bloomington, Ill.: Pantagraph, 1899): 2730; and Ezra M. Prince, The Fourth Illinois Regiment in the War with Mexico, Transactions of the Illinois State Historical Society 11 (Springfield: Illinois State Journal, 1906): 17287. 31 Karl Marx, Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy, trans. Martin Nicolaus (New York: Penguin, 1993), 693. For links among free-labor republicanism, flight from the cities, and expansion, see Thomas R. Hietala, Manifest Design: American Exceptionalism and Empire (1985; reprint, Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell Univ. Press, 2003), 55131; as well as the fascinating case study of artisan radical George Wilkes in Alexander Saxton, Rise and Fall of the White Republic: Class Politics and Mass Culture in Nineteenth-Century America (London: Verso, 2003), 20526. 32 Lyrics from the popular song The Leg I Left behind Me, originally published in Jacob Oswandel, Notes of the Mexican War: 184618471848 (Philadelphia: n.p., 1885); cited in Alemn, Ethnic in the Canon, 17071. 33 George C. Furber, The Twelve Months Volunteer: Or, Journal of a Private, in the Tennessee Regiment of Cavalry, in the Campaign, in Mexico, 184647 (Cincinnati, Ohio: James, 1857), 601. 34 George Ballantine, Autobiography of an Eng lish Soldier in the United States Army (New York: Stringer and Townsend, 1853), 197. Coincidentally, before joining the military Ballantine nearly goes a-whaling, referring to his desire to see some of those scenes of enchantment of which the inimitable Herman Melville has given such charming and graphical descriptions in his Typee and Omoo (11). 35 I borrow this phrase from Bruce Robbins, The Servants Hand: Eng lish Fiction from Below (Durham, N.C.: Duke Univ. Press, 1993), ix. 36 George W. Stratton, Siege of Mexico, Or, The Confrere of Mechanics: A Melo-drama, in Three Acts (founded on the Mexican War) (Milwaukee, Wisc.: n.p., 1850), 5, 39. 37 See Melvilles Authentic Anecdotes of Old Zack, in Piazza Tales, ed. Hayford, MacDougall, and Tanselle, 21229. See also Luther Stearns

Ahab, Santa Anna, and Moby-Dick55 Mansfield, Melvilles Comic Articles on Zachary Taylor, American Literature 9 ( January 1938): 41118. One of the ironies of this letter is that Melville wrote it after Gansevoort had died in London on 12 May 1846, one day after the declaration of war by the U.S. Congress (see Correspondence, ed. Horth, 39). Herman Melville, Mardi: And a Voyage Thither (1849; reprint, New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 1973), 436. See Harrison, Temple and the Forum, ix46. Bluford Adams relates that cross-class encounters were common both at the Broadway and Ann Street Museum . . . and at Barnums second Museum at 539 and 541 Broadway. In decades that saw New Yorks neighborhoodsand the amusements that catered to themsplinter along lines of class and ethnicity, everybody went to Barnums ( E Pluribus Barnum: The Great Showman and the Making of U.S. Popular Culture [Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 2007], 7576). Harrison, Temple and the Forum, 105. See Adams, E Pluribus Barnum, 120. As Diana Taylor points out, museums are both places and practices (The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas [Durham, N.C.: Duke Univ. Press, 2003], 63.) See Adams, E Pluribus Barnum, 83. Shelley Streeby, American Sensations: Class, Empire, and the Production of Popular Culture (Berkeley and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press, 2002), 5. William Knight Northall writes, We never had the smallest confidence in Santa Annas wooden leg; and always thought it was about the lamest affair [Barnum] ever undertook to palm off upon the public ( Before and behind the Curtain; or, Fifteen Years Observations among the Theatres of New York [New York: W. F. Burgess, 1851], 162). This is likely, but not certain. As a result of the fire that consumed that museum in 1860, most of the exhibitionary apparatus was lost. Neil Harris, Humbug: The Art of P. T. Barnum (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1981), 57. Adams, E Pluribus Barnum, 83, 85. Melville, View of the Barnum Property, 448. Ibid. Jacques Derrida, The Law of Genre, trans. Avital Ronell, Critical Inquiry 7 (autumn 1980): 5581. For a concise formulation of invagination, see Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Love Me, Love My Ombre, Elle, Diacritics 14 (winter 1984): 2021. See Streeby, American Sensations, 6975. Hugh Haralson, Congressional Globe, 29th Cong., 1st sess., 1846, 793. Lewis Cass argued, A Mexican army is upon our soil. Are we to confine

38

39 40 41

42 43 44

45 46

47

48 49 50 51 52 53

54 55 56

56American Literature

57 58

59 60

61

62 63

our efforts to repelling them? Are we to drive them to the border, and then stop our pursuit, and allow them to find refuge in their own territory? And what then? To collect again to cross our frontier at some other point, and again to renew the same scenes . . . ? The advantage would be altogether on the side of the Mexicans, while the loss would be altogether ours. . . . I am for making the defense effectual by not only driving off the enemy, but by following them into their own territory, and by dictating a peace even in the capital, if it be necessary (Congressional Globe, 29th Cong., 1st sess., 1846, 799). Frederick Jackson Turner, The Frontier in American History (New York: Henry Holt, 1920), 2. Thomas Paine, The American Crisis 4, 12 September 1777 (Philadelphia: Styner and Cist, 1777); epigraph for George Lippard, Legends of Mexico (Philadelphia: T. B. Peterson, 1847), title page. Ian McGuire, Who aint a slave? Moby-Dick and the Ideology of Free Labor, Journal of American Studies 37 (August 2003): 293. It should be noted that whalers in general appear to be opposed to U.S. imperialism in Mexico. The primary expressive mode of whalers the shantyindicates a stiff resistance to U.S. territorial imperialism. Shanties rewrote the history of the imperial encounter in favor of Mexico. In Walk Me Along, Johnny, sailors sang: Oh, General Taylor died long ago / Hes gone, me boys, where the winds dont blow. / He died on the fields of ol Monterry / An Santiana he gained the day. Santiana contains a similar rewriting of history, with the addition that Santa Anna is figured as a whaler who dies on board a ship: Oh, Santiana now we mourn, / We left him buried off Cape Horn. Stan Hugill claims that many British seamen left their boats to fight on the side of the Mexicans during the war, perhaps providing discursive material for these ballads. These shanties were explosively popular. When the last U.S. whaler was decommissioned in the early twentieth century, Santiana was the final shanty sung. That this history of resistance is entirely absent is significant. Instead, Ishmael declares, Let America add Mexico to Texas ( MD, 70). Melville is not providing a real-historical response to the Mexican War; rather, he is using the ship as an analytical unit in order to investigate the process of hegemony formation. See Stan Hugill, Shanties from the Seven Seas: Shipboard Work-Songs and Songs Used as Work-Songs from the Great Days of Sail (London: Routledge, 1980), 7087. Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, in Surveys from Exile: Political Writings, Volume 2, ed. David Fernbach (New York: Vintage, 1974), 239. Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics (London: Verso, 2001), xiii. Ibid., xi.

Ahab, Santa Anna, and Moby-Dick57 64 Leslie Katz, Flesh of His Flesh: Amputation in Moby-Dick and S. W. Mitchells Medical Papers, Genders 4 (March 1989): 2. 65 Harrison, Temple and the Forum, 105. 66 Neil L. Tolchin, Mourning, Gender, and Creativity in the Art of Herman Melville (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press, 1988), 131. 67 Unskilled whalers averaged $6.20 per month in 1845, $9.43 in 1848, and $9.85 in 1851. Captains averaged $66.62, $106.09, and $119.93 per month for those same years. See Lance E. Davis, Robert E. Gallman, and Karin Gleiter, In Pursuit of Leviathan: Technology, Institutions, Productivity, and Profits in American Whaling, 18161906 (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1997), 176. 68 The Conquest of Mexico! An Appeal to the Citizens of the United States, on the Justice and Expediency of the Conquest of Mexico; with Historical and Descriptive Information Respecting That Country (Boston: Jordan and Wiley, 1846), 15. 69 Ibid., 16 70 See Clayton Charles Kohl, Claims as a Cause of the Mexican War (New York: New York Univ. Press, 1914). Although the scholarship is obviously dated, it usefully and exhaustively tracks a deep history of claims and counterclaims between Mexico and the United States. 71 James Duban, A Pantomime of Action: Starbuck and American Whig Dissidence, New Eng land Quarterly 55 (September 1982): 43239. 72 Economistic arguments against the war were abundant. Theodore Parker argued that the Mexican War resulted in a massive withdrawal of workers from the countrys labor supply: The indirect pecuniary cost of the war is caused, first, by diverting some 150,000 men . . . from the works of productive industry, to the labors of war, which produce nothing . . . . The withdrawal of such an amount of labor from the common industry of the country must be seriously felt ( A Sermon of the Mexican War [Boston: 1848], 13); Similarly, Abiel Abbot Livermore claimed that the energies of many thousand men in both countries ha[d] been diverted from industrial and productive occupations (The War with Mexico Reviewed [Boston: American Peace Society, 1850], 88).

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Case Questions - Grocery GatewayDocument4 pagesCase Questions - Grocery GatewayPankaj SharmaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Revlon Case Report - Big BossDocument32 pagesRevlon Case Report - Big BossMohd EizraNo ratings yet

- TAVISTOCK Psychialry MK-ULTRA EIR PDFDocument8 pagesTAVISTOCK Psychialry MK-ULTRA EIR PDFHANKMAMZERNo ratings yet

- Deirdre J. Wright, LICSW, ACSW P.O. Box 11302 Washington, DCDocument4 pagesDeirdre J. Wright, LICSW, ACSW P.O. Box 11302 Washington, DCdedeej100% (1)

- Edtpa Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesEdtpa Lesson Planapi-280516383No ratings yet

- Sushil - Poudel - Resume SampleDocument1 pageSushil - Poudel - Resume SampleSushil PaudelNo ratings yet

- Indian Bank - Education Loan Application FormDocument2 pagesIndian Bank - Education Loan Application Formabhishek100% (4)

- Pe ReviewerDocument3 pagesPe Reviewerig: vrlcmNo ratings yet

- Teaching Note Archer Daniels Midland Company: Case OverviewDocument7 pagesTeaching Note Archer Daniels Midland Company: Case OverviewRoyAlexanderWujatsonNo ratings yet

- Ethics (Merged)Document54 pagesEthics (Merged)Stanley T. VelascoNo ratings yet

- Vax Cert PHDocument1 pageVax Cert PHRulen CataloNo ratings yet

- Quill Corp. v. North Dakota, 504 U.S. 298 (1992)Document28 pagesQuill Corp. v. North Dakota, 504 U.S. 298 (1992)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Mahatma Gandhi BiographyDocument5 pagesMahatma Gandhi BiographyGian LuceroNo ratings yet

- Current Affairs of February 2024Document36 pagesCurrent Affairs of February 2024imrankhan872019No ratings yet

- Microeconomics Corso Di Laurea in Economics and Finance Mock 1 Partial ExamDocument9 pagesMicroeconomics Corso Di Laurea in Economics and Finance Mock 1 Partial ExamĐặng DungNo ratings yet

- 451research Pathfinder RedHat Mobile and IoTDocument13 pages451research Pathfinder RedHat Mobile and IoTP SridharNo ratings yet

- Entrepreneurial Journey of Richard BransonDocument7 pagesEntrepreneurial Journey of Richard Bransondolly saggarNo ratings yet

- Tlm4all@NMMS 2019 Model Grand Test-1 (EM) by APMF SrikakulamDocument8 pagesTlm4all@NMMS 2019 Model Grand Test-1 (EM) by APMF SrikakulamThirupathaiahNo ratings yet

- Homework PET RP1EXBO (26:2)Document3 pagesHomework PET RP1EXBO (26:2)Vy ĐinhNo ratings yet

- Integration of Circular Economy in The Surf Industry - A Vision Aligned With The Sustainable Development GoalsDocument1 pageIntegration of Circular Economy in The Surf Industry - A Vision Aligned With The Sustainable Development GoalsVladan KuzmanovicNo ratings yet

- Decoding A Term SheetDocument1 pageDecoding A Term Sheetsantosh kumar pandaNo ratings yet

- GST - E-InvoicingDocument17 pagesGST - E-Invoicingnehal ajgaonkarNo ratings yet

- Silas Engineering Company ProfileDocument6 pagesSilas Engineering Company Profilesandesh negiNo ratings yet

- Summary (Nido)Document3 pagesSummary (Nido)G21. Villanueva, Camille T.No ratings yet

- Numismatics - An Art and Investment.Document4 pagesNumismatics - An Art and Investment.Suresh Kumar manoharanNo ratings yet

- 81 Department of Commerce PDFDocument17 pages81 Department of Commerce PDFDrAbhishek SarafNo ratings yet

- Ch01 Forwrd and Futures, OptionsDocument34 pagesCh01 Forwrd and Futures, Optionsabaig2011No ratings yet

- Mario ComettiDocument4 pagesMario ComettiMario ComettiNo ratings yet

- Bhim Yadav - Latest With Changes IncorporatedDocument38 pagesBhim Yadav - Latest With Changes IncorporatedvimalNo ratings yet

- JointTradesMATSLetter FinalDocument4 pagesJointTradesMATSLetter FinaljeffbradynprNo ratings yet