Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Beef Blackleg Clostridial Diseases

Beef Blackleg Clostridial Diseases

Uploaded by

Yan Lean DollisonOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Beef Blackleg Clostridial Diseases

Beef Blackleg Clostridial Diseases

Uploaded by

Yan Lean DollisonCopyright:

Available Formats

"#$!%!&'! ! !

Blackleg and Clostridial Diseases

The Clostridial diseases are a group of mostly fatal infections caused by bacteria belonging to the group called Clostridia. These organisms have the ability to form protective shell-like forms called spores when exposed to adverse conditions. This allows them to remain potentially infective in soils for long periods of time and present a real danger to the livestock population. Many of the organisms in this group are also normally present in the intestines of man and animals. Black Leg Blackleg is a disease caused by Clostridium chauvoei and primarily affects cattle under two years of age and is usually seen in the better doing calves. The organism is taken in by mouth. Symptoms first noted are those of lameness and depression. A swelling caused by gas bubbles, often can be felt under the skin as a crackling sensation. A high temperature is present. Occasionally, sudden death occurs with no symptoms observed. Upon a post mortem examination, the infected area is composed of black, dead (necrotic) muscle which is pocked with gas bubbles and is usually found in the heavier more active muscle masses of the animal. A sweetish odor of rancid butter may be detected from a fresh lesion. Lesions may occasionally be discovered in the diaphragm, heart or tongue. Diagnosis is based on the symptoms of lameness with a gaseous swelling under the skin in young cattle and is confirmed by post mortem and laboratory tests. The chances for survival are poor unless symptoms are discovered early in the disease. Large doses of penicillin may save the life of the animal if administered early. Prevention is readily accomplished, by the use of Blackleg bacterins which over the years have proven very effective. Vaccination at less than 4 months of age will not produce a lasting immunity. Calves vaccinated at less than 4 months should be revaccinated at 5-6 months. Malignant Edema Malignant edema is a disease of cattle of any age caused by CI. septicum is found in the feces of most domestic animals and in large numbers in the soil where livestock populations are high. The organism gains entrance to the body in deep wounds and can even be introduced into deep vaginal or uterine wounds in cows following difficult calving. The symptoms are those primarily of depression, loss of appetite and a wet doughy swelling around the wound which often gravitates to lower portions of the body. Temperatures of 106 or more are associated with the infection with death frequently occurring in twenty-four to forty-eight hours. Post mortem lesions seen are those of necrotic, darkened foul smelling areas under the skin, often extending into muscle. Very little if any gas is associated with the swelling. Diagnosis is based on the history of illness in unvaccinated cattle, typical symptoms and post mortem lesions with laboratory confirmation. Treatment with massive doses of penicillin in cases observed early is occasionally successful. The disease can be prevented by the use of Clostridium septicum bacterins usually produced in combination with other bacterins. Clostridium Novyi Infections caused by Cl. novyi, infrequently called Black disease, in cattle, occur sporadically in cow-calf operations as they are more often seen under feedlot conditions. The route of infection and transmission are not known, however, it is thought to gain entrance into the body by a wound infection, or possibly taken in orally. Only sudden deaths are thought to occur and sick cattle are not generally recognized. Post mortem lesions are similar to those of CI. septicum with a wet, foul smelling lesion being present. Diagnosis is based on the history of sudden death, significant post mortem lesions and

positive laboratory confirmation on fresh tissue. No treatment is recognized due to the sudden death aspect of the disease. Clostridium novyi bacterins are available in combination with other Clostridial bacterins and are generally thought to offer greater and more solid protection with two injections given four to six weeks apart. Clostriduim Sordellii CI. sordellii is a sudden death disease of primarily feedlot cattle, infrequently seen in cows. The route of transmission is unknown, but thought to be by mouth. No symptoms are observed as only dead animals are found. The post mortem findings are somewhat specific, as they tend to be found in the areas of brisket and throat, consisting of massive black hemorrhage and smelly muscle necrosis with no gas formation. No treatment is of value as sick animals are not observed. The diagnosis is based on the history of sudden death, with the typical post mortem lesions of the brisket and throat and by laboratory confirmation. Clostridium sordellii bacterins are available. Tetanus Tetanus in cattle is caused by CI. Tetani. Although cattle are less susceptible to tetanus than most other animals, it can occur. The organism lives in the intestines of many animals and is found widespread in soil. The organism is introduced into wounds created by punctures or lacerations caused either by accident or following "dirty surgery." The organism does not actively invade tissues creating a larger more noticeable wound, but remains in the small area where introduced and produces powerful toxins or poisons which primarily attack nerve tissue affecting both the spinal cord and brain. The symptoms observed are those of muscle spasms, sometimes violent, brought about by sudden sounds or touch. The spasms make normal locomotion difficult and animals are often seen uncoordinated in early cases. Also, in early stages, the ears are erect, the tail stiff and elevated and the third eyelid located in the corner of the eye is seen to protrude partially across the eye. In general, about 60% of affected untreated cattle die. No lesions are found post mortem, and only occasionally can the original offending wound be found. Diagnosis therefore, is based on typical clinical signs and perhaps the history of a recent wound. Treatment consists of tranquilization of the animal and antibiotics, preferably penicillin to stop the organisms from producing further toxin. Tetanus antitoxin may be used in large doses but

some question its effectiveness in treatment. Supportive treatment to prevent dehydration and starvation may need to be given for 1-4 week. Prevention is best accomplished by making sure lots and pasture areas are free from objects which might cause puncture wounds and by accomplishing surgical procedures as cleanly as possible. In areas of high risk, tetanus antitoxin can be given at the time of surgical procedures. Clostridium Hemolyticum CI. hemolyticum causes an infection commonly called red water disease. The disease has somewhat limited geographic locations, occurring mostly in Montana and along the coast of Texas, being found primarily in marshy lowlands. The organism taken in orally is frequently associated with liver fluke infection. Liver tissue damage caused by the flukes allows the bacteria to proliferate, grow and produce powerful toxins which destroy red blood cells, spilling the released red hemoglobin into the urine, hence the name red water disease. Symptoms seen are those of depression, anemia, bloody diarrhea, red stained urine, high temperature, collapse and death in 1-3 days. Post mortem lesions are those of an extremely pale animal, red stained urine in the bladder, thin watery blood and usually a large necrotic area in the liver. Treatment is usually of no avail unless begun early. Large doses of penicillin may help. A bacterin is available for use in areas where the disease appears, but must be given every six months. In heavily infected areas more frequent vaccination may be necessary. Enterotoxaemia This disease condition perfringens. is caused by Cl.

This organism is found throughout the world in the lower intestinal tract of man and animals. The disease entity seen most frequently in the cowcalf operation is hemorrhagic enterotoxaemia, caused by Cl. perfringens type C. There does seem to be somewhat of a geographical limitation to the condition, as it is seen most frequently in the mountain states and the western part of Kansas, Nebraska, South and North Dakota. It is, however, seen sporadically in the remainder of the Great Plains area. As Cl. perfringens is a normal inhabitant of almost all mammals, a specific set of circumstances must exist in order for the disease to present itself to the animal. (a) The type C strain of the bacteria must be present in the intestinal tract. (b) The bacteria must have an abundance of nutrients, especially carbohydrates for the bacteria to attack, as for instance, would be present in milk and (c) there must be at least a

partial slow down or stoppage of intestinal tract movement brought about by ingesting a particularly large amount of feed allowing the toxins to accumulate and be absorbed in the gut. These conditions could be met in the case of a young vigorous week old calf, who, after exercise develops a real hunger and drinks more than its normal amount of milk from a good milking dam, overloads its digestive tract and the right conditions exist. The disease is usually seen then in calves one week of age or less. Although riders may find only dead calves, more often the symptoms observed are those of acute abdominal pain as evidenced by kicking at the stomach and straining. Later the calves go down, frequently go into "paddling" type convulsions and die usually within 12 hours after symptoms are noted. Infrequently a bloody diarrhea may develop prior to death. At post mortem one finds spectacular lesions of an extremely reddened section of small intestine, several inches to several feet in length which can be easily seen as soon as the abdominal wall is opened. A blood-tinged thick fluid is found when the gut is opened; Hemorrhages may be found on the heart and thymus as well. Diagnosis is based on the typical clinical symptoms and the spectacular lesion at post mortem. A definitive diagnosis can be made in the laboratory with gut content; however, it must be collected and frozen or delivered to the laboratory within six hours of death. There is no treatment of value as the animals almost always die following the appearance of symptom. The disease can be prevented by giving the calf an injection of Clostridium perfringens Type C Antitoxin (antiserum) as soon as possible after birth. One preventive injection seems to protect almost all of the calves through the dangerous early period of life. A more efficient method of protection however, if there is a history of a problem with the disease on the premises, is to vaccinate the cows with Clostridium perfringens Type C Toxoid. Two doses are given during pregnancy and a yearly booster thereafter. This allows the cow to produce her own antitoxin in the colostrum and therefore protects the calf after nursing. Sporadic outbreaks of type D enterotoxaemia do occur but infrequently, usually occurring in calves after weaning and while on dry feed. Calves dying of type D do not show the spectacular bloody intestinal lesions at post mortem but have hemorrhages on the heart and thymus. A laboratory confirmation is necessary to absolutely diagnose type D. Types C.& D enterotoxaemia of course do occur

in feedlot cattle, but rarely in mature stock cows. Botulism Botulism, caused by CI. botulinum occurs only rarely in the United States and has only been reported in Texas. The organism is found as a contaminant in feeds usually present in a decomposing animal, such as a rabbit or rat, which as it grows in the small animal, produces a powerful toxin which leaks out into the surrounding feedstuff and cattle ingest the contaminated feed. The symptoms are those of a progressive paralysis ending in death. No significant lesions are present at post mortem. No treatment is of value. Since the disease is so sporadic and rare no preventive bacterins are available for cattle. Diagnosis must be based on presumptive evidence and definitive diagnosis is almost impossible. Clostridium Biological Products The following biological products (bacterins, antitoxins and toxoids) for immunizing cattle against Clostridial diseases have been licensed by USDA for production in the United States. Some of the less widely used products may not be available in all areas. Consult your local veterinarian for his recommendations for your particular herd health program. Bacterins 1. Clostridium chauvoei *Pasteurella hemolytica-multocida 2. Clostridium chauvoei *Pasteurella multocida 3. Clostridium chauvoei Clostridium septicum 4. Clostridium chauvoei Clostridium septicum 5. Clostridium chauvoei *Pasteurella hemolytica-multocida 6. Clostridium haemolyticum Clostridium septicum

*Causes secondary bacterial pneumonia

Antitoxins 1. Clostridium perfringens type D 2. Clostridium perfringens type C 3. Clostridium perfringens type C & D Bacterin- Toxoids 1. Clostridium chauvoei Clostridium septicum Clostridium novyi 2. Clostridium chauvoei Clostridium novyi Clostridium soredellii 3. Clostridium chauvoei Clostridium septicum Clostridium novyi Clostridium perfringens C & D 4. Clostridium novyi 5. Clostridium novyi Clostridium soredellii

6. 7. 8. 9.

Clostridium novyi Clostridium perfringens types C & 0 Clostridium perfringens type C Clostridium perfringens type D Clostridium perfringens types C & D

Common terminology of disease conditions Caused by:

Clostridium chauvoei- blackleg Clostridium chauvoei - malignant edema Clostridium novyi - black disease Clostridium soredellii - big head Clostridium perfringens C & enterotoxaemia or overeating.

D-

Summary The Clostridial diseases as a group present a unique problem in control and diagnosis. The cow-calf operator should work closely with his local veterinarian in evaluating the prevalence of these agents in his area. As was noted in the discussion, prompt post mortem examinations and tissue collection for laboratory testing are essential for an accurate diagnosis.

You might also like

- Lesson Plan Breastfeeding PDFDocument13 pagesLesson Plan Breastfeeding PDFSrikutty Devu85% (20)

- Confined Space Permit PDFDocument2 pagesConfined Space Permit PDFrashid zaman100% (1)

- Blackleg and Other Clostridial Diseases in CattleDocument3 pagesBlackleg and Other Clostridial Diseases in CattleYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Enterotoxemia, Anaerobic Dysentery, Bradsot, Botulism and NecrobacteriosisDocument17 pagesEnterotoxemia, Anaerobic Dysentery, Bradsot, Botulism and NecrobacteriosisNajafova SuadaNo ratings yet

- Anthrax Black LegDocument20 pagesAnthrax Black LegCary PriceNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Clostridium Species in Cattle and SheepDocument2 pagesAn Overview of Clostridium Species in Cattle and SheepRobert Marian RăureanuNo ratings yet

- Clostridial infections-LR3Document8 pagesClostridial infections-LR3yomifNo ratings yet

- Cysticercosis (Panneerselvam Gowtham 90A)Document13 pagesCysticercosis (Panneerselvam Gowtham 90A)Gautam Josh100% (1)

- Gram Positive BacilliDocument6 pagesGram Positive BacilliSteve ShirmpNo ratings yet

- Enterotoxaemia: SynonymsDocument5 pagesEnterotoxaemia: SynonymsMd Shamim AhasanNo ratings yet

- Lec 15Document9 pagesLec 15surendradeora3628No ratings yet

- Anaerobic Spore-Forming Bacteria: S.Y.MaselleDocument41 pagesAnaerobic Spore-Forming Bacteria: S.Y.MaselleMasali MacdonaNo ratings yet

- AnthraxDocument27 pagesAnthraxSantosh BhandariNo ratings yet

- What Is Bacillus AnthracisDocument6 pagesWhat Is Bacillus AnthracisFrancis AjeroNo ratings yet

- Animal DiseasesDocument27 pagesAnimal DiseasessandraespinosaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 Viral Diseases of RuminantsDocument15 pagesChapter 4 Viral Diseases of RuminantsJAD IMADNo ratings yet

- Lam 2Document33 pagesLam 2bishal.ad.002No ratings yet

- AnthraxDocument6 pagesAnthraxeutamène ramziNo ratings yet

- Taeniasis Cyst Guideline PDFDocument11 pagesTaeniasis Cyst Guideline PDFAustine OsaweNo ratings yet

- Gastrointestinal Disease of CattleDocument64 pagesGastrointestinal Disease of CattleRikka LaugoNo ratings yet

- ROLL NO 30 (Assignment On Zoonotic Importance of Nematodes)Document3 pagesROLL NO 30 (Assignment On Zoonotic Importance of Nematodes)barsha subediNo ratings yet

- Abdelfattah Monged Selim - Tetanus 2Document25 pagesAbdelfattah Monged Selim - Tetanus 2Saja MaraqaNo ratings yet

- 1.2 - Bacillus AnthracisDocument26 pages1.2 - Bacillus Anthracissajad abasNo ratings yet

- Echinococcosis AsiyaDocument20 pagesEchinococcosis AsiyaBiswadeepan AcharyaNo ratings yet

- Cattle Meat Inspeccion Chapter 1Document45 pagesCattle Meat Inspeccion Chapter 1MIGAJOHNSON100% (1)

- Diseases - What Is Q Fever (Query Fever) What Causes Q Fever (Medical News Today-16 June 2010)Document5 pagesDiseases - What Is Q Fever (Query Fever) What Causes Q Fever (Medical News Today-16 June 2010)National Child Health Resource Centre (NCHRC)No ratings yet

- Typhoid FeverDocument37 pagesTyphoid FeverMuqtadir “The Ruler” KuchikiNo ratings yet

- Dairy Cattle DiseasesDocument14 pagesDairy Cattle DiseasesLaddi SandhuNo ratings yet

- Granulosus and E. Multilocularis (Hydatid) .: Tenia Solium or T. Saginata (Teniasis)Document7 pagesGranulosus and E. Multilocularis (Hydatid) .: Tenia Solium or T. Saginata (Teniasis)moosNo ratings yet

- Soliuminfections and Not Infection With Taniea Saginata.: Pathogenesis & EpimiologyDocument2 pagesSoliuminfections and Not Infection With Taniea Saginata.: Pathogenesis & EpimiologyraphaelNo ratings yet

- TetanusDocument7 pagesTetanusKimchi LynnNo ratings yet

- Cdnursing PPT 2021Document37 pagesCdnursing PPT 2021yuuki konnoNo ratings yet

- Selma CestodesDocument23 pagesSelma CestodesAhmed EisaNo ratings yet

- Clostridium Tetan1Document4 pagesClostridium Tetan1Jul SkynEtNo ratings yet

- Zoonotic DiseasesDocument96 pagesZoonotic DiseasesWakjira GemedaNo ratings yet

- Brief Introduction To Protozoan Diseases of PoultryDocument5 pagesBrief Introduction To Protozoan Diseases of Poultrykarki Keadr Dr100% (4)

- BLACKQUARTERDocument4 pagesBLACKQUARTERMd Shamim AhasanNo ratings yet

- Clinical ManifestationDocument6 pagesClinical ManifestationKrystal Jane SalinasNo ratings yet

- Bakteri ClostridiumDocument39 pagesBakteri ClostridiumEuuzNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 Bacterial Diseases of Ruminants 2020Document30 pagesChapter 5 Bacterial Diseases of Ruminants 2020JAD IMADNo ratings yet

- Coccidiosis: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention: Training What Is Coccidiosis?Document8 pagesCoccidiosis: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention: Training What Is Coccidiosis?cigar77No ratings yet

- Taenia Saginata and SoliumDocument46 pagesTaenia Saginata and SoliumKotilakshmanareddy TetaliNo ratings yet

- Bacillus and Biological Warfare: Dr. Samah Binte Latif M - Phil (Part-1), Microbiology Dhaka Medical CollegeDocument67 pagesBacillus and Biological Warfare: Dr. Samah Binte Latif M - Phil (Part-1), Microbiology Dhaka Medical CollegeTania.dmp20No ratings yet

- GANGRENEDocument2 pagesGANGRENEJonathan SchillerNo ratings yet

- Top Five Lethal InfectionsDocument3 pagesTop Five Lethal InfectionsRodney Langley100% (1)

- Kuliah Cestode & Trematode (Hand-Out)Document13 pagesKuliah Cestode & Trematode (Hand-Out)made yogaNo ratings yet

- Large Animal Medicine PPt2016Document221 pagesLarge Animal Medicine PPt2016kibrushe260No ratings yet

- Rabbit DiseasesDocument315 pagesRabbit DiseasesABOHEMEED ALY100% (1)

- Cryptosporidium ParvumDocument7 pagesCryptosporidium ParvumKalebNo ratings yet

- Dr. Nadia Aziz C.A.B.C.M. Department of Community Medicine Medical College, Baghdad UniversityDocument49 pagesDr. Nadia Aziz C.A.B.C.M. Department of Community Medicine Medical College, Baghdad UniversityMazinNo ratings yet

- Large A.medicine 4th YearDocument285 pagesLarge A.medicine 4th YearAssefaTayachewNo ratings yet

- Food Hygeine MeatsDocument27 pagesFood Hygeine MeatsStevenNo ratings yet

- Anthrax 2012 ReportDocument6 pagesAnthrax 2012 ReportAko Gle C MarizNo ratings yet

- TaeniasisDocument66 pagesTaeniasisM Lutfi Fanani100% (1)

- (WIDMER E A) Flesh of Swine (Ministry, 1988-05)Document3 pages(WIDMER E A) Flesh of Swine (Ministry, 1988-05)Nicolas MarieNo ratings yet

- Hookworm RephraseDocument6 pagesHookworm Rephrasecooky maknaeNo ratings yet

- Clostridial Diseases in Cattle PDFDocument4 pagesClostridial Diseases in Cattle PDFMuhammad JameelNo ratings yet

- Enteric FeverDocument7 pagesEnteric FeverkudzaimuregidubeNo ratings yet

- Notes on Diseases of Cattle: Cause, Symptoms and TreatmentFrom EverandNotes on Diseases of Cattle: Cause, Symptoms and TreatmentNo ratings yet

- Q-fever, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandQ-fever, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- 911 Pigeon Disease & Treatment Protocols!From Everand911 Pigeon Disease & Treatment Protocols!Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Jud AffDocument4 pagesJud AffYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Buzzdock Ads: Kumonekta Sa Mga Kaibigan Online. Sumali Sa Grupong Facebook - Libre!Document3 pagesBuzzdock Ads: Kumonekta Sa Mga Kaibigan Online. Sumali Sa Grupong Facebook - Libre!Yan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Breaking BadDocument3 pagesBreaking BadYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Penalties in GeneralDocument30 pagesPenalties in GeneralYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- In God's Will, I Will Become A Lawyer. Pray, Study Hard and Everything Will Follow. Atty (.) Rhea L. DollisonDocument1 pageIn God's Will, I Will Become A Lawyer. Pray, Study Hard and Everything Will Follow. Atty (.) Rhea L. DollisonYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Cus Tom KƏSTƏM/ : "The Old English Custom of Dancing Around The Maypole" Synonyms:, ,, ,, ,,, M OreDocument1 pageCus Tom KƏSTƏM/ : "The Old English Custom of Dancing Around The Maypole" Synonyms:, ,, ,, ,,, M OreYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Sanc Tion Sang (K) SH (Ə) NDocument2 pagesSanc Tion Sang (K) SH (Ə) NYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Philippine Tariff FinderDocument1 pagePhilippine Tariff FinderYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Construing Bigamy and Articles 40 and 41: What Went Wrong?Document13 pagesConstruing Bigamy and Articles 40 and 41: What Went Wrong?Yan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- VatDocument1 pageVatYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- GalaxyDocument1 pageGalaxyYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Levels of Organization: LEVEL 1 - CellsDocument2 pagesLevels of Organization: LEVEL 1 - CellsYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Biology: For Other Uses, SeeDocument1 pageBiology: For Other Uses, SeeYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- For Other Uses, See and - This Article Is About A - For The Theory of Law, See - "Legal Concept" Redirects HereDocument2 pagesFor Other Uses, See and - This Article Is About A - For The Theory of Law, See - "Legal Concept" Redirects HereYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Cir Vs AlgueDocument2 pagesCir Vs AlgueYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

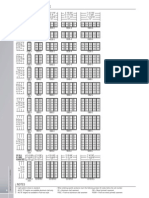

- Sizing Windows 400series Casement Casement AwningtransomDocument3 pagesSizing Windows 400series Casement Casement AwningtransomYan Lean Dollison100% (1)

- Ethics: (Eth-Iks) IPA SyllablesDocument1 pageEthics: (Eth-Iks) IPA SyllablesYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Filipino Drama in Japanese PeriodDocument1 pageFilipino Drama in Japanese PeriodYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

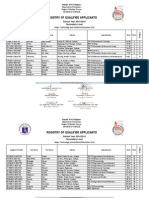

- Registry of Qualified Applicants: School Year 2014-2015 Secondary LevelDocument5 pagesRegistry of Qualified Applicants: School Year 2014-2015 Secondary LevelYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Casement ElevationsDocument10 pagesCasement ElevationsYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- SPES 2015 Application FormDocument1 pageSPES 2015 Application FormYan Lean DollisonNo ratings yet

- Del Rosario Vs FerrerDocument2 pagesDel Rosario Vs FerrerYan Lean Dollison100% (1)

- As ISO 10993.8-2003 Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices Selection and Qualification of Reference MateriaDocument8 pagesAs ISO 10993.8-2003 Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices Selection and Qualification of Reference MateriaSAI Global - APACNo ratings yet

- Neet AnaesthesiaDocument233 pagesNeet AnaesthesiaASHISHNo ratings yet

- Iso TS 22330-18Document46 pagesIso TS 22330-18adenorla1100% (5)

- Finnish Aged Care GlossaryDocument25 pagesFinnish Aged Care GlossaryVeronicaGelfgren100% (1)

- Targeted Individuals (TIs) and Electronic HarassmentDocument4 pagesTargeted Individuals (TIs) and Electronic HarassmentIJRASETPublicationsNo ratings yet

- International Bio-Gas Enterprises (Latest)Document25 pagesInternational Bio-Gas Enterprises (Latest)Om Prakash100% (1)

- S Under The MicroscopeDocument41 pagesS Under The MicroscopeBruno SarmentoNo ratings yet

- Animal Teeth vs. Human Teeth PPT (Teacher Version)Document14 pagesAnimal Teeth vs. Human Teeth PPT (Teacher Version)Allison LeCoqNo ratings yet

- Catalogue Process English 2017Document85 pagesCatalogue Process English 2017Badea DanielNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Fire Protection R2Document64 pagesFundamentals of Fire Protection R2khalid mansourNo ratings yet

- MIS 107 - Literature Review - by Dr. AbdullahDocument3 pagesMIS 107 - Literature Review - by Dr. AbdullahMunjir Abdullah 2112217030No ratings yet

- Analysis of Laboratory Critical Value Reporting at A Large Academic Medical CenterDocument7 pagesAnalysis of Laboratory Critical Value Reporting at A Large Academic Medical CenterLevi GasparNo ratings yet

- The Burns Depression ChecklistDocument2 pagesThe Burns Depression Checklistim247black50% (2)

- The Ultimate Ultramarathon Training PlanDocument6 pagesThe Ultimate Ultramarathon Training Plansinclaire90210No ratings yet

- MSK 72 SHAMBHU KUMAR GUPTA - InsurnceDocument1 pageMSK 72 SHAMBHU KUMAR GUPTA - InsurnceAnil SharmaNo ratings yet

- Updated Census TimelineDocument4 pagesUpdated Census TimelineinforumdocsNo ratings yet

- View PublicationDocument16 pagesView PublicationpmilyNo ratings yet

- Coconut Whipped Cream Recipe - Minimalist Baker RecipesDocument2 pagesCoconut Whipped Cream Recipe - Minimalist Baker RecipesJune LeeNo ratings yet

- BOLT StudyDocument11 pagesBOLT Studytiago_nelson100% (1)

- Orthopaedic Instruments and ImplantsDocument21 pagesOrthopaedic Instruments and ImplantsgibreilNo ratings yet

- Kettlebell Workouts 2Document10 pagesKettlebell Workouts 2NoBannerNo ratings yet

- PT. Bina Mitra Jaya BersamaDocument26 pagesPT. Bina Mitra Jaya BersamaAdhiemax SsNo ratings yet

- MACD FormDocument44 pagesMACD FormNik ShNo ratings yet

- Cesarean Section: Name-Vishnu Kumar Bairwa Roll No.-132Document24 pagesCesarean Section: Name-Vishnu Kumar Bairwa Roll No.-132vishnu kumarNo ratings yet

- TranscriptionDocument5 pagesTranscriptionNecka AmoloNo ratings yet

- Excretion in Humans 1 QPDocument9 pagesExcretion in Humans 1 QPBritanya EastNo ratings yet

- Venofer Venofer Iron Infusion Nursing Care PlanDocument2 pagesVenofer Venofer Iron Infusion Nursing Care PlanErica Ruth CabrillasNo ratings yet

- Sigma VikoteDocument3 pagesSigma VikoteimranNo ratings yet