Professional Documents

Culture Documents

WB Yeats Society of NY - 2013 Poetry Competition Report

WB Yeats Society of NY - 2013 Poetry Competition Report

Uploaded by

Adam Rabb CohenCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

WB Yeats Society of NY - 2013 Poetry Competition Report

WB Yeats Society of NY - 2013 Poetry Competition Report

Uploaded by

Adam Rabb CohenCopyright:

Available Formats

Sing what is well made

W.B. Y EATS S OCIETY OF N.Y.

Kaplan strategizes her poem , and none of it feels artificial or forced. And the feeling that the poem carries is powerful, no m atter how sim ple the statem ents in it. M ary Legato Brownells second-prize poem has a cinem atic quality, a step-by-step, highly detailed walk back into the past during which the poets cam era-eye m isses nothing because the sacred place that is returned to m ust be approached with reverence for every m em ory it contains. At the sam e tim e in this return-tothe-past narrative, there is a philosophical dram a unfolding. Can w e ever return to place of joy that is now contam inated by experience, by loss? The language the poet (or her surrogate) drafts back into is the language of tears and regret. There is no going back, but poetry can recoup som ething of tem ps perdu because poetry is inextricably joined to m em ory. And poets are fated to rem em ber, whether tears com e or not. Again, the em otional power com es through the accrual of m inute particulars that are charged with feeling for the narrator. W e get a bit of Ireland in M argaret J. H oehns poem , and m aybe the difference between New Y ork and D ublin is that m essages there are still chalked on the sidewalk. (Here it is m ostly hopscotch diagram s, directions to Verizon technicians, or Boticelli paintings in full color.) M s. H oehns poem is a straightforward plea not to turn aw ay from a m irror im age of our own loss presented by chance to us in all its nakedness in the street. I liked the full-feeling here, the risk of sentim entality that in fact skirts the sentim ental because of the first-rate em ploym ent of details. Last year Victoria Givotovsky also won a runner-up award. She consistently writes excellent poem s. In The Door we are led into a night world that is as disorienting as it is ours. Som etim es we are condem ned to wander through our ow n room s as if they were a prison of blacks and greys punctuated by disturbing sounds, our own hope that the darkness will eventually attenuate into gray, the first signal that m orning is on its way. The river a shim m er, a trick of light atop green tow, is the first line of Nan B eckers untitled poem . Tow is the coarse and broken part of flax or hem p prepared for spinning; or a bundle of untwisted natural or m an-m ade fibers.. So the river is w oven or pre-woven here, a kind of art product. The poem s com plex unfolding bears this out in a Stevensian way that echoes with m usic. But an inner narrative em erges that is not unlike that of M ary Legato Brownells poem . A ll that went before we m et and after left, she tells us; we appropriate life gone. H ear it hear what w ould be here. W hat would guess whatever we had was separate. So am id the rhapsody com es the sorrow, but as a dull regret and without tears; rather with the m em ory of birdsong and flight. B ut now whatever the narrator and the im plied listener had is separate. W hereas M s. Brownell stalks and is stalked by every past m om ent, M s. Becker has to fight through her visions (her poetry) to find the feeling, but the feeling com es.

O ur last runner-up is Francesca Capossela. Her poem Going south appealed to m e with its toughness and Kerouackian feeling. H it the road, she tells us, but all the wild im ages that appear to the traveler on the road are frightening, som etim es even degrading, pushing one towards thievery and sex. This kind of travel is really flight, which I suppose leads to discoveries of a sort, but the discovery here, the poet tells us, is transcontinental sadness, guiding you hom e to, one supposes, another kind of static sadness. This poem has terrific m ovem ent and m ore than a little desperation. Its im agery is original and powerful, and m ore than suggests that a real poet is driving the car. As we think about these poem s and reread them , I want to thank Andrew M cGowan and D on Bates and the other m em bers of the W . B . Y eats Society who m ake this annual contest possible, and who have been kind enough to ask m e to judge it for the past two years. I think that Am erican poetry is traveling through a very rich period, and that this richness is reflected in the poem s of these winners.

shoots her a dirty look. I agree, it would be a good story, but I dont think its one I could write because m y grandm a would never rem ove her num ber. I know then that I cant ever get a tattoo because her num ber will always be there, a perm anent souvenir of pain far worse than needles, far deeper than ink in skin, so anything I write on m y body will be trivial, no, an insult. Though I never would do such a thing the only tattoo I could get would be m y grandm as num ber.

2013 Poetry Competition

R EPORT OF THE JUDGE

ast year I picked three poets from M assachusetts as winners of this contest; this year I have picked all wom en, though I didnt know that when I was m aking m y choices, of course.

A year ago I didnt hazard a guess about why so m any good poets cam e to the contest from M assachusetts, but m aybe it wont be out of order if I speculate on the fact that all of this years winners are fem ale. I am not going to say that wom en are better poets than m en. But wom en poets often have som ething that poetry deeply needs, and that m any m en dont have, or have in sm all supply, and that is a direct line to feeling. M en often spend a lot of tim e living in their heads. W om en often prim arily grasp the world with w hat C. G. Jung called the feeling function, one of the Four Functions in his fam ous system of hum an types that includes thinking, sensation, and intuition. W e dont get a purchase on reality through only a single function, though, and Jung m ade this clear; the dom inant function has a wing function that is alm ost as highly developed as the dom inant function. Allied to feeling would either be sensation (how the world com es to us through our senses) or intuition and of course the word wom ens has not been long joined to the word intuition for nothing. I wont go further into Jungs system right now, but its som ething that a poet m ale or fem ale m ight look into. In his thinking these Functions are also directly linked to introversion and extraversion, whether one has an outgoing personality or lives m ore inwardly. After a little study, you m ight be able to find yourself in Jungs system , and discover that you are a thinkingintuitive type who is an extravert. At which point you can go to work on your feeling function and your sensation function, trying to create what used to be called a well-rounded personality. As we know, Y eats loved system s of this kind, so I dont feel that Im going out on a lim b by bringing in a few of Jungs ideas. Alisha Kaplan, a runner-up in last years contest, took first prize this year with a poem that begins casually, with its persons chatting about tattooing, and swiftly and skillfully brings us to realization that not all tattoos are frivolous. Indeed, they have been for m illions a sym bol of life and death. The poem m ade m e rem em ber when the M ill Luncheonette on Broadway near Colum bia U niversity was owned and operated by Jews whose tattooed num bers were im possible to m iss as they handed you a dish of ice cream . (Today the establishm ent is called the Korean M ill Luncheonette.) I love the clarity and econom y with which M s.

Bill Zavatsky

F IRST P RIZE

S ECOND P RIZE You Must Drift Back Into The Language That Is Your Language

by Mary Legato Brownell, Jenkintown PA

I turn from the curb on 17th near C hestnut and w alk past the parking attendants, and remember having handed them the w orn keys to my car w hen w e w ould arrive, how kind they w ere and how naive I w as as they opened the doors and lifted our suitcases, your computer, our canvas book bags, sometimes a grocery sack of sparkling w ater, bananas, cashew s. Tw o naval oranges. Biscotti Id baked for you the day before your plane w ould land. All this I remember in a compression of images and sounds as iridescent and divisional as the cardinal I now w atch each evening as he cuts the w aning light of summer into startling facts, sw ooping across the small yards of my neighborhood in an endless search for instincts place to pause. U nder a stone portico, the hotel entrance w as framed in granite carvings of small leaves, and opened to an elevator paneled in rose w alnut w hose mechanisms of movement w ere so polished w ith lavender oil, I could not feel them, invisible as they w ere to any sense of my ow n bodys gravity. Framed in thin strips of pounded brass, the elevator doors closed to the disappearing ground and opened seconds later, thirty feet above, to the marbled continent of the lobby . I remember the flush and w hisper of those doors, the domestic secret of being alone w ith you, briefly, for an inscrutable moment of tenderness, the w ay I felt as you checked us in that the coming days and nights w ere to be an outliers show dow n, that I w as an outlier, too. I know , now , that in a life you must drift back into the language that is your language. I remember the hotel bar, its arched entrance, and hesitate tonight, w alking instead to the nearby Ladies R oom to w ash my hands and close my eyes. I remember telling

A-6876

by Alisha Kaplan, Brooklyn NY

Its Sunday afternoon and were sitting on m y roof, talking about tattoos. D am ian wont get one because he likes the idea of being pure. Lulu would if she wasnt afraid of needles. Jane has three and I think theyre all stupid but I would never tell her that. I tell them how I want to get a Zen Buddhist sym bol but I wouldnt because Im not a poser and I couldnt be buried in a Jewish cem etery and it would probably kill m y grandm other. Then, as the H olocaust often sneaks its way into m y conversations, I m ention her num ber. D am ian asks if she ever considered getting it rem oved. Jane says it would be a great story to write about. Lulu

you about the startling pow er of the hand dryers force, how the skin over my fingertips vibrated as the moisture w as w hisked aw ay. I loved that w e laughed over that. I dry my hands tonight as I did then, and w alk to the bars entrance as if there is a sound I have suddenly forgotten. Against the nearest w all, the same small couches are upholstered in a soft red fabric w oven in Spain. W e settled best in public places in churches, in synagogues, seats in restaurants, seats on benches, seats on buses. In hotel bars w e ordered scotch; sometimes martinis. C offee once. The bartender alw ays brought a small w hite bow l of almonds mixed w ith raisins and sunflow er seeds, and w ed lay out the ceremony of our pens and napkin scraps of w ords. Today Im sitting on my side of the far couch. D eep pillow s cushion the w ood curve of its back. I have taken out my black pen, my paper, my list. The bartender has brought a small w hite bow l of almonds, settling it to the small table in front of me. A balding man at a far-end stool tells the w oman leaning to him that someday he w ants to take a submarine trip, not in a glass-bottom tourist boat, w here looking into the sea mirrors the inside of a w ell-groomed fish tank, but one in w hich the air pressure is countered, and the hallw ays are w ide enough for only one person to w alk along at a time. He tells her that his children are nineteen and fifteen. She tells him shes been to Haw aii, that he should go someday because he w ill never eat such fresh fish in his life if he doesnt. He thinks she is dazzling. W hen the bartender brings my scotch, I asked her if I can sit here for a w hile, and confess that I am not a guest in the hotel. She smiles. O f course I can, and then I cry, drifting back into the language that is my language.

why we look away from this m an as we skirt around him , why we don't hold him in our arm s and help him to stand. H ow else to explain why we act as if nothing is am iss in a world where one of us is m issing, and another is on his knees willing him self to becom e the N orth Star or whatever else it m ight take to bring the lost hom e.

The Door

by Victoria Givotovsky, Cornwall Bridge CT

as when you wake late into the night and sounds sound strange in the dark a door banging som ewhere the wind shifting where you can't see and your feet find the floorboards m ove carefully along the corridor until you reach the other room where you lie down on a sheet-straightened bed still hearing the door som ewhere bum p into its fram e the noise at unexpected intervals startles you so you turn on a light and leaf through a book but the print does not speak to you in the sam e way as the stuttering door speaks to you so you turn off the light the room suddenly ablaze with black and you listen until the door stops its halting sentences and your eyes see how the night has shifted how the sky fattens into gray

Hit the road Because theres nowhere to go but down. Nothing to do but fall. W atching Kansas fly by through the rainy window, like a kid curled up in a sterilized sitting room or on the floor of a hospital ward, whispering to you through m iles of traffic and hundreds of relapses and seconds to spare till they know This is your transcontinental sadness, guiding you hom e.

Untitled

by Nan Becker, Newton NJ

The river a shim m er, a trick of light atop green tow, bloom s sideways, ripples that answer the winds calling. Eases then, when enam el still, yields as if its lost sight of its persuasion, knowing neither trouble nor fatigue. It does not seem to bother with breath but waits suddenly a great believer in surprise. W aves, the theys follow,

N ational Arts Club 15G ram ercy Park South N ew York N Y 10003 www.YeatsSociety.org

H ONORABLE M ENTIONS For the Man Outside a Shelter in Dublin Who is Writing on the Sidewalk

by Margaret J. Hoehn, Sacramento CA

M ichael please com e hom e we love you the door is unlocked and is always open The anarchy of grief can clutch a m an's hand and set it in m otion, can com pel him to kneel on the sidewalk beneath the cottonwoods' blur of silver, and print both prayer and poem in chalk with words so bare they throw open the doors and windows of his house so all who walk by can see inside the room s where he lives. And in our looking we m ight see our own tired faces m irrored back, our own shabby cupboards of loss and regret. H ow else to explain

pools of them selves, silent shadows that m ove like an old sadness changing its m ind, gentled by passing life after life concurring to go through, to go on, all that went before we m et and after left, guessing though guessing, none of it m eans terrible things, or joyous we appropriate life gone, unsentim entally, none of it m eaning harm , although it does, did, and like a birds tip-toe, leaning , it calls. Hear it hear what would be here. H ear the downy drum behind a robins slow purdy, hear the whom p of a heron flying low over a river that stream s a stone. W ho would guess whatever we had was separate.

Going south

by Francesca Capossela, Brooklyn NY

H it the road. not hard enough to lose consciousness but firm ly, the way you would slap your lover, if you had the kind of lover that needed to be slapped, or the guts to hurt som eone, so that when you pick your head up, pulled over on the side of the road by the m uddy M ississippi, you m ean to be there. Reflected in hollow eyes, the white lines glide under your tires like synchronized swim m ers. Like cellphones in outer space these open planes and everglades are too artificial. Painted like a postcard, written like a slant rhym e. Y ou get tired of the open road when going to go is dead and gone and over the payphone your m om is belligerent and then saccharine and she wants you hom e again. There are clichd coffee grinds and gas station loners that glide their greasy eyes over your greasy body. you pay seven dollars to use their shower and the soap sm ells like m elons and cigarettes and tears. Y oud like to steal the stars out of the bruised sky like the candy bars you pocket in grocery stores. Y oud like to photograph the car lights m oving to the beat of the radio.

The W.B. Yeats Society of New York poetry competition is open to members and nonmembers of any age, from any locality. Poems in English up to 60 lines, not previously published, on any subject may be submitted. Each poem (judged separately) typed on an 8.5 x 11-inch sheet without authors name; attach 3x5 card with name, address, phone, e-mail. Entry fee $8 for first poem, $7 each additional. Mail to 2011 Poetry Competition, WB Yeats Society of NY, National Arts Club, 15 Gramercy Park S, New York NY 10003. Include S.A.S.E. to receive the report like this one. List of winners is posted on YeatsSociety.org around March 31. First prize $500, second prize $250. Winners and honorable mentions receive 2year memberships in the Society and are honored at an event in New York in April. Authors retain rights, but grant us the right to publish winning entries. These are complete guidelines; no entry form necessary. Deadline for 2014 competition is February 1. We reserve the right to hold late submissions to following year. For information on our other programs, or on membership, visit YeatsSociety.org or write to us.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Wergle Flomp - The Poems That Started It AllDocument7 pagesWergle Flomp - The Poems That Started It AllAdam Rabb Cohen100% (1)

- Elm Street Historic District: Round Hill Road Extension - Preliminary Study ReportDocument20 pagesElm Street Historic District: Round Hill Road Extension - Preliminary Study ReportAdam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- An Essay On The True Art of Playing Keyboard Instrument HandoutDocument2 pagesAn Essay On The True Art of Playing Keyboard Instrument HandoutKrystian Sekowski33% (3)

- Table of Use and Dim Regs URCDocument5 pagesTable of Use and Dim Regs URCNorthampton City Councilor At-Large Ryan O'DonnellNo ratings yet

- Beautiful Italian ViolinsDocument111 pagesBeautiful Italian Violinsedosartori50% (2)

- White TempleDocument12 pagesWhite TempleYna VictoriaNo ratings yet

- Northampton Zoning For URBDocument6 pagesNorthampton Zoning For URBAdam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- DPW Meeting About North Street 2012-06-25Document1 pageDPW Meeting About North Street 2012-06-25Adam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Northampton in 2030Document23 pagesContemporary Northampton in 2030Adam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- Table of Use and Dim Regs URADocument4 pagesTable of Use and Dim Regs URANorthampton City Councilor At-Large Ryan O'DonnellNo ratings yet

- DPW Responds To Petition On North Street Reconstruction 05-24-2012Document2 pagesDPW Responds To Petition On North Street Reconstruction 05-24-2012Adam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- Appeals Court Affirms Land Court Decision Against Kohl ConstructionDocument1 pageAppeals Court Affirms Land Court Decision Against Kohl ConstructionAdam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- CDM Northampton Stormwater System Assessment and Plan 2012-05 Vol 2 AppendicesDocument243 pagesCDM Northampton Stormwater System Assessment and Plan 2012-05 Vol 2 AppendicesAdam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- CDM Northampton Stormwater System Assessment and Plan 2012-05 Vol 1Document93 pagesCDM Northampton Stormwater System Assessment and Plan 2012-05 Vol 1Adam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- DPW: North Street Information, June 10, 2010Document4 pagesDPW: North Street Information, June 10, 2010Adam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- Don't by Shevaun BranniganDocument1 pageDon't by Shevaun BranniganAdam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- North Street Presentation 2012-03-06Document20 pagesNorth Street Presentation 2012-03-06Adam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- Charter Drafting Committee Agenda 2011-11-30 RevisedDocument1 pageCharter Drafting Committee Agenda 2011-11-30 RevisedAdam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- Planning Board Agenda 12-08-2011Document2 pagesPlanning Board Agenda 12-08-2011Adam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- City Charter Forum II Final 12-06-2011Document17 pagesCity Charter Forum II Final 12-06-2011Adam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- North Street Layout Concepts 2012-03-01Document3 pagesNorth Street Layout Concepts 2012-03-01Adam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- Northampton Finance Director Report For 12-15-2011Document2 pagesNorthampton Finance Director Report For 12-15-2011Adam Rabb CohenNo ratings yet

- Baroque: UK: US: FrenchDocument38 pagesBaroque: UK: US: FrenchNicole BalateñaNo ratings yet

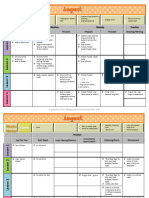

- 00 Kinder Year Long 2013Document20 pages00 Kinder Year Long 2013Tan SamNo ratings yet

- Punk's Not Dead!Document30 pagesPunk's Not Dead!andra_nic2005No ratings yet

- Event ManagementDocument13 pagesEvent ManagementSidhotam Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- Set Online KarateDocument1 pageSet Online Karateponomarr.ssNo ratings yet

- Organ 49Document68 pagesOrgan 49ZebulonNo ratings yet

- Experiences With Holbein Palettes - WetCanvasDocument7 pagesExperiences With Holbein Palettes - WetCanvasfrazNo ratings yet

- 2013 Royal Design Studio Stencil Product Catalog ISSUUDocument62 pages2013 Royal Design Studio Stencil Product Catalog ISSUUNur AiniNo ratings yet

- Title PagesDocument83 pagesTitle PagesbolshNo ratings yet

- Economics G11 STDocument369 pagesEconomics G11 STAsrat AyalewNo ratings yet

- 0-14 Tower, Dubai, UAEDocument20 pages0-14 Tower, Dubai, UAEalditikos100% (1)

- Sands CapesDocument3 pagesSands CapesMakv2lisNo ratings yet

- Japan and America's Influence On Each Other's Culture: Kent Katsuda South Lyon High School February 2017Document7 pagesJapan and America's Influence On Each Other's Culture: Kent Katsuda South Lyon High School February 2017kentkatsudaNo ratings yet

- xORDIN 600-2018Document193 pagesxORDIN 600-2018CosminNo ratings yet

- Pettey CVDocument6 pagesPettey CVapi-293980858No ratings yet

- Barch Vii MesraDocument7 pagesBarch Vii MesrachaithanyaNo ratings yet

- Babbitt OrientDocument1 pageBabbitt OrientNinel GaneaNo ratings yet

- Coulee Roots BujinkanDocument19 pagesCoulee Roots BujinkanGodsniper100% (2)

- Ged0117 Sec102 Fa1binuya - MirandaDocument2 pagesGed0117 Sec102 Fa1binuya - MirandaSamantha Lauren BinuyaNo ratings yet

- Plato and The PaintersDocument21 pagesPlato and The PaintersZhennya SlootskinNo ratings yet

- كتلوج سيراميك كليوباترا الاول2008Document74 pagesكتلوج سيراميك كليوباترا الاول2008tamer nady100% (2)

- ADocument14 pagesANguyen Le Khanh ChauNo ratings yet

- Lucy Ravenscar - Star Wars Mini Amigurumi Chewbacca (C)Document7 pagesLucy Ravenscar - Star Wars Mini Amigurumi Chewbacca (C)Joy100% (2)

- America's Favorite Classical Music Bloopers: TestsDocument4 pagesAmerica's Favorite Classical Music Bloopers: TestsjammesNo ratings yet

- Foggy Glass DiseaseDocument9 pagesFoggy Glass DiseaseClef GonadanNo ratings yet

- 7.the National Artists of The Philippines For ArchitectureDocument19 pages7.the National Artists of The Philippines For Architecturebhojo100% (1)

- Paris Ward CVDocument1 pageParis Ward CVapi-430150049No ratings yet