Professional Documents

Culture Documents

On The Composition of The Prototractatus - The Philosophical Quarterly-2005-Kang-1-20

On The Composition of The Prototractatus - The Philosophical Quarterly-2005-Kang-1-20

Uploaded by

Riko PiliangOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

On The Composition of The Prototractatus - The Philosophical Quarterly-2005-Kang-1-20

On The Composition of The Prototractatus - The Philosophical Quarterly-2005-Kang-1-20

Uploaded by

Riko PiliangCopyright:

Available Formats

ON THE COMPOSITION OF THE PROTOTRACTATUS

Bv Jixno K\xo

Wittgensteins Prototractatus raises dicult textual questions concerning both its structure and the

date of its composition. I provide an account of the structure of the Prototractatus by investigating

the hitherto unexplored connections between it and other early Wittgenstein manuscripts. I then con-

sider the two most inuential proposals on its date of composition, made by von Wright and

McGuinness, and argue that neither of them stands up to scrutiny. I make an alternative suggestion,

and discuss its implications for the signicance of the Prototractatus in the study of Wittgensteins

early philosophy.

I

In :q6, G.H. von Wright found a previously unknown Wittgenstein manu-

script in Vienna. An examination of the manuscript indicated that it was

divided into two parts that had rather dierent characters. The rst goes up

to the rst remark on p. :o

1

and contains an apparently early version of

the Tractatus: it bears the original German title of the Tractatus, Logisch-

Philosophische Abhandlung, and contains most of the remarks we nd in

the Tractatus, as well as its dedication and motto.

2

The actual wording of

these remarks is not exactly the same as that of the corresponding remarks

in the Tractatus, though the dierences are minor in many cases. Each of the

remarks has its number, and the numbering is substantially dierent from

that of the corresponding remarks. Moreover, the remarks in the manuscript

are not arranged according to their numbers. The second part starts from

the second remark on p. :o and goes up to p. :.:, where pp. ::q.: are

devoted to a preface virtually identical with that in the Tractatus. Unlike the

remarks in the rst part, all but six remarks in the second part have exactly

1

Most pages of the manuscript have their page numbers, and I follow them in this paper.

The rst couple of pages are unnumbered, however, and I cite them by indicating the ordinal

numbers corresponding to their order in the manuscript.

2

Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, tr. C.K. Ogden (London: Routledge, :q..),

tr. D. Pears and B. McGuinness (London: Routledge, :q6:). References to the remarks of

the Tractatus are made by their numbers. Unless indicated otherwise, I follow Pears and

McGuinness translation.

The Philosophical Quarterly, Vol. , No. :.8 January :oo

ISSN oo.8o

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo. Published by Blackwell Publishing, q6oo Garsington Road, Oxford ox .n, UK,

and o Main Street, Malden, x\ o.:8, USA.

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

the same numbers as their counterparts (the six exceptions occur on

pp. :o8q, with their numbers enclosed in square brackets), and their word-

ing is also completely identical in most cases. These features strongly suggest

that the remarks in the second part were directly incorporated into the

Tractatus. In collaboration with Brian McGuinness and Tauno Nyberg, von

Wright subsequently rearranged the remarks of the rst part of the

manuscript in order of their numbers and published the result in :q: under

the title Prototractatus.

3

PT is undeniably a welcome addition to the pre-Tractatus Wittgenstein

manuscripts we have today, which chiey include the :q: Notes on Logic

(hereafter NL), the :q: Notes Dictated to G.E. Moore (hereafter MN), and

the three wartime notebooks which Wittgenstein wrote from August :q: to

January :q: (hereafter NB :, NB . and NB respectively).

4

On the other

hand, however, PT is a problematic document, raising dicult textual ques-

tions regarding its composition. Two problems are particularly pressing.

First, it is not clear how Wittgenstein composed PT. This problem arises

because PT is not an independent work but is mostly based on Wittgen-

steins other manuscripts, the passage on the front page of PT indicating that

the majority of its remarks come directly from them (I shall return to this

passage in the next section). It is inconceivable that Wittgenstein extracted

the remarks in PT from other manuscripts entirely at random, without any

organizing principle: there must be some rough structure. But what kind of

structure? As I have already said, the remarks in PT are not arranged

according to their numbers, and in many cases they are not organized

thematically either, all too often jumping unexpectedly from one topic to

another which does not seem to be related. Indeed, it is very hard to see

what sort of organizing principle could be operative behind the apparently

chaotic assemblage of the remarks in PT.

Secondly, it is not clear when Wittgenstein wrote PT. Unlike the three

wartime notebooks that were essentially the diaries Wittgenstein kept, PT

does not contain any explicit date regarding its composition. Again, unlike

NL and MN,

5

whose dates of composition can easily be gured out from

. JINHO KANG

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

3

B. McGuinness et al. (eds), Prototractatus, tr. Pears and McGuinness (London: Routledge,

:q:, :qq6). The original manuscript is reproduced in facsimile in the book. In what follows I

refer to the rst part of the original manuscript, not the reconstructed version by McGuinness

et al., as PT. Similarly, the page numbers of the remarks I cite from PT are as they occur in the

manuscript, not as they are in the reconstructed version. I follow Pears and McGuinness

translation unless otherwise indicated.

4

All these manuscripts are published in one volume: G.H. von Wright and G.E.M.

Anscombe (eds), Notebooks ...., .nd edn (Oxford: Blackwell, :qq). NL and MN appear as

two appendices of the book.

5

For NL, see McGuinness and von Wright (eds), Ludwig Wittgenstein: Cambridge Letters

(Oxford: Blackwell, :qq, hereafter Letters), pp. ::. For MN, see Letters, pp. 88, :o..

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

Wittgensteins reference to them in his letters to Russell, we do not have any

letters or testimonies in which PT is explicitly mentioned. Hence the date of

its composition remains essentially a matter of conjecture, and this raises the

question of where we should locate PT in the overall development of

Wittgensteins early philosophy.

The aim of this paper is to shed light on these two problems surrounding

the composition of PT. In the next section, I shall provide an account of its

structure by investigating the hitherto unexplored connections between PT

and other early Wittgenstein manuscripts. In the following section I shall

then consider the two most inuential proposals about the date of composi-

tion of the Prototractatus, oered by von Wright and McGuinness, and argue

that neither of them stands up to scrutiny. I shall make an alternative

suggestion, and discuss its implications for the signicance of PT in the study

of Wittgensteins early philosophy.

II

A careful look at PT reveals a very interesting feature that seems to me to

provide a key to its structure: several horizontal lines are inserted among its

remarks. There are seven such lines, on pp. .8, ., 6o, 6, o, : and 8.

6

An

abrupt change of topic or numbering always takes place across these lines,

and this indicates that each block separated by a line comprises a somewhat

independent section of PT.

Of course, the hard question is how they are independent of one another.

To start with the rst section beginning on p. and ending on p. .8, a

notable feature of it is that it contains almost all the remarks with major

numbers up to 6 all those with a one-digit number from : to 6 and almost

all those with two- and three-digit numbers prior to 6.

7

In other words, the

section contains most of the remarks that form the framework of PT. For this

reason, I shall call this section the Core-Prototractatus, or Core-PT for short.

Core-PT has another noteworthy feature: the remarks in it do not seem to

originate from the manuscripts we have. Only a handful of remarks can be

traced in these, and few of them are verbatim citations.

8

On the front page of

PT Wittgenstein writes:

ON THE COMPOSITION OF THE PROTOTRACTATUS

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

6

The seven or eight further lines from p. :o onwards need not be my concern here: as I

have said, the part that comes after the rst remark on p. :o is not likely to belong to PT.

7

There are :oo such major remarks in PT; no fewer than 88 of them occur in the section

pp. .8. The exceptions are :.., :..:, .., .o8, .oq, ..:, ..., .., ., ., .: and ...

8

There are : such remarks out of the entire .8 remarks of Core-PT. In order of

appearance, they are .oq (NB, p. 8), ... (NL, p. :o), .o6 (NB, p. ), .o (NB, p. ), ..::

(NB, p. .), ..::6 (NB, p. :), .o:: (NL, p. :oo), .:oo: (NL, p. :o6), .. (NB, p. ), ..

(NB, p. ), ..: (NB, p. ), . (NB, p. ), .:o.. (NB, p. .) and .o:: (NB, p. ).

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

Among these propositions [diese Stze]

9

are inserted [gefgt ] all the good propositions

from my other manuscripts. The numbers indicate the order of the propositions and

their importance. Thus .o:o: follows .o: and is followed by .o::, which is a

more important proposition than .o:o:.

Here Wittgenstein uses the phrase these propositions, whose reference is

not clear. The passage indicates that the propositions meant are not from

other manuscripts of Wittgensteins. The passage also suggests that they

contain the remarks with major numbers, for Wittgenstein says that the

remarks from his other manuscripts are inserted among them. A possible

hypothesis concerning the origin of Core-PT, then, is that the remarks in it

are none other than what Wittgenstein refers to as these propositions in the

above passage. If we follow this hypothesis, presumably Core-PT was newly

written as Wittgenstein was composing PT. This would then explain why

only a handful of remarks in Core-PT can be traced in the other manuscripts

we have.

Another possible hypothesis is that what Wittgenstein refers to as these

propositions are not the entire remarks of Core-PT but those on p. , and

that the subsequent remarks up to p. .8 originate from some missing

manuscript (or manuscripts). We can plausibly conjecture from Elizabeth

Anscombes and Paul Engelmanns testimonies (Introduction, p. ) that

several manuscripts of Wittgensteins early period were destroyed, so there is

no diculty in positing the existence of missing manuscripts. Also, p. by

itself contains all the remarks with a one-digit number from : to 6 as well as

nine out of thirteen remarks with two-digit numbers prior to 6. In fact, I am

inclined towards this hypothesis, for it strikes me as far-fetched to suppose

that Wittgenstein means by these propositions in the above passage the

entire Core-PT ranging from p. to p. .8. Even if we adopt this hypothesis,

however, the original source for Core-PT must still have been no ordinary

manuscript, but must have contained a summary of Wittgensteins whole

work up to the time of composing PT, for otherwise we cannot explain why

the majority of remarks with three-digit numbers prior to 6 are contained in

pp. .8 of Core-PT (there are 8: such remarks in PT, and : of them occur

on pp. .8 of Core-PT).

Next come the remarks on pp. .8.. Those from .oq: on p. .8 to ..:

on p. show a striking common feature: they are drawn exclusively from

NL. Conclusive evidence for this is not only that almost all the remarks on

pp. .8 have their counterparts in NL, but also that the order of the

JINHO KANG

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

9

Pears and McGuinness translate diese Stze as the propositions in this book, which I

nd misleading. Accordingly I have modied their translation. Von Wright suggests a trans-

lation similar to mine in his Historical Introduction: the Origin of Wittgensteins Tractatus

(hereafter Introduction), in McGuinness et al. (eds), Prototractatus, pp. :, at p. , fn. :.

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

remarks corresponds almost exactly with the order of their appearance in

NL.

10

Together with the fact that there is no recognizable pattern in terms of

numbering or themes of those remarks, it shows beyond doubt that Wittgen-

stein composed pp. .8 of PT by transferring the remarks either directly

from NL or from a manuscript containing NL.

A similar pattern can also be found in the block from .oq: on p. o to

.o:: on p. .. Many remarks here are drawn from NB :., though in this

case they are intertwined with a number of remarks that do not appear in

NB :., and the order of the remarks that do appear do not follow the order

in NB :. as strictly as those on pp. .8 follow the order in NL. Among

the manuscripts we currently possess there is a signicant gap between

June :q: (when NB . was nished) and April :q:6 (when NB was begun),

during which period we do not have any manuscripts available. Wittgen-

stein reports in his letter of .. October :q: to Russell that he has recently

done a great deal of work and quite successfully, so much so that he is now

summarizing his whole work in the form of a treatise [Abhandlung].

11

Wittgenstein would not have written like this if he had not kept on working

after completing NB . in late June of :q:. This is even more plausible given

that he fails in NB . to come up with a settled view on the problems he was

wrestling with in June :q:, those of simples and of analysis (NB, pp. q:).

I thus conjecture that the remarks on pp. o. of PT which cannot be

found in NB :. originate from Wittgensteins work done during the period

immediately following the completion of NB ., and were probably kept in a

manuscript that is now missing.

What about the remarks from .o: on p. to .o on p. o?

Though we can nd the sources for about a fth of these remarks in NL,

MN and NB :.,

12

the rest of them do not occur in any of the manuscripts

we have. But given that the remarks on pp. .8 come from NL, and a

signicant portion of pp. o. from NB :., it is natural to suppose that

those on pp. o are mainly from a manuscript Wittgenstein composed

ON THE COMPOSITION OF THE PROTOTRACTATUS

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

10

o out of the entire 6 remarks from .oq: on p. .8 to ..: on p. belong to this

category. The six exceptions are ...::, .oo:6, .:oo:, .:oo:, .o. and ..:,

although ..: can be traced to a passage in NL, p. q6. None of them can be found in other

manuscripts we have. Incidentally, Wittgensteins original German manuscript of NL is un-

fortunately lost, and we have only Russells English translation of NL. Even through the lens of

Russells translation, however, we cannot fail to recognize the obvious correspondence.

11

Wittgensteins postcard to Frege on . August :q: suggests that he in fact started the

summarizing by late August. Unfortunately the postcard is lost, but we still have Heinrich

Scholzs summary of it. See Frege, Wissenschaftlicher Briefwechsel, ed. G. Gabriel et al. (Hamburg:

Felix Meiner, :q6), p. .66. I am indebted to Warren Goldfarb for reminding me of the

existence of this postcard.

12

There are :o such remarks out of : .o. (MN, p. ::), .oq. (NL, p. :o), .o8 (NB,

p. ), .o8: (NB, p. ), .o8. (NB, p. ), .8: (MN, p. :o8 and NB, p. ), .:6o:

(NL, p. :o), .:6o. (NB, p. :), .. (NB, p. ) and .o. (MN, p. ::).

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

between NL and NB :.. We know from a :q: letter from Wittgenstein to

Russell (Letters, pp. q.) that he was working on a now missing manuscript

while staying in Norway during October :q:June :q:, the time that

comes precisely between the composition of NL and that of NB :..

Therefore I propose that the chief source of the remarks on pp. o is the

missing Norway manuscript. This proposal initially seems to meet a

diculty, for only three remarks on pp. o can be traced in MN (see

fn. :. above), and MN is none other than the notes Moore took when Witt-

genstein was explaining the main ideas he developed during the Norway

period.

13

But precisely because MN is Moores notes of Wittgensteins explan-

ation, there is no guarantee that it is faithful to what Wittgenstein actually

wrote down in the missing Norway manuscript. Indeed, an examination of

another manuscript, NL, suggests that that is probably not the case: NL con-

tains a summary which Wittgenstein dictated to Russell as well as his four

manuscripts. We nd, however, that hardly any of the remarks in the

summary are verbatim citations from the four manuscripts, and also that

the remarks on pp. .8 of PT come almost exclusively from the four

manuscripts of NL and not from the summary. Therefore I do not think that

the mismatch between pp. o and MN raises a serious problem.

Moreover, there is evidence that supports my proposal: the topics

addressed in the block on pp. o are those with which Wittgenstein was

chiey engaged during or before October :q:June :q:. For example, the

block starts with remarks on the nature of identity, and we can see from

Wittgensteins letters from October to December :q: that he was much

troubled by this problem.

14

Other topics that occur on pp. o include the

impossibility of saying the form of a proposition, tautologies and contra-

dictions, philosophy as a critique of language, proper introduction of the

primitive signs of logic, dierences between names and propositions, and

accompanying criticism of Freges view of propositions as names. These are

indeed the familiar themes one can nd in NL and MN.

15

On the other

hand, it is signicant that of the ideas Wittgenstein develops after June :q:

(e.g., picture theory, formal series, operation N, and numbers as indices of

operations I shall talk more about formal series and operation N in the

6 JINHO KANG

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

13

Here I rely on the following remark of Wittgenstein in his :q: letter to Russell: ... I

explained [my work] in detail to Moore when he was with me and he made various notes. So

you can best nd it all out from him (Letters, p. 88).

14

Identity is the very Devil! , writes Wittgenstein to Russell on : October :q: (Letters, p. :).

See also Letters, pp. , , 8, , 6o, 6..

15

As is fairly well known, the say/show distinction and the idea of tautology and

contradiction are two principal themes in MN. For philosophy as a critique of language, see

NL, pp. :o6; for a proper introduction of the primitive signs of logic, see MN, pp. :::8; for

the dierence between propositions and names, see NL, pp. q8q and MN, p. ::. and p. ::6;

for criticism of Freges view of propositions as names, see NL, p. q.

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

next section), none appears on pp. o, which gives further plausibility to

my proposal concerning the origin of the remarks on these pages.

If my conjecture so far is on the right track, we may conclude that the

section pp. .8. comes from the ve manuscripts of Wittgenstein roughly

in their chronological order: pp. .8 from NL; pp. o from the missing

Norway manuscript; pp. o. from NB :, NB . and a missing manuscript

immediately following NB .. But would these manuscripts have been the

direct sources for pp. .8. of PT ? This does not seem to be the case.

Rather, presumably what happened is that Wittgenstein had another manu-

script which contained the selection and revision of all those manuscripts,

and that he worked with this manuscript to compose pp. .8. of PT.

A recently found letter from Wittgensteins sister suggests that there was

indeed a manuscript of such a character. The letter contains a list of

Wittgensteins manuscripts by January :q:, as follows:

(:) A large Chancery volume (handwritten; a corrected typescript also exists)

(.) Two quarto volumes (handwritten; corrected typescripts also exist)

() A single quarto volume (part of it already exists in typewritten form)

() A single octavo volume (handwritten only; every proposition verbatim in

order without any correction)

() A large Chancery volume (contains the revision of (:) and (.) for

publication).

16

In an article concerning the history of pre-Tractatus manuscripts, Mc-

Guinness argues convincingly that items (:) and (.) are the missing Norway

manuscript and NB :., respectively (I shall not consider his argument here,

as it would take me too far aeld).

17

Assuming McGuinness argument, item

() then turns out to be a manuscript containing the revision of the Norway

manuscript and NB :., and my conjecture is that it was this manuscript

from which Wittgenstein extracted the remarks on pp. .8. of PT. This

conjecture may initially sound problematic, given that neither NL nor the

missing manuscript (which I suppose to have immediately followed NB .) is

mentioned among the manuscripts covered in item (). But there is room for

an answer. Regarding NL, it is likely that the Norway manuscript also

contained NL and not just the work Wittgenstein did during the Norway

period (this is also McGuinness hypothesis; see Manuscripts, p. .6:). The

ON THE COMPOSITION OF THE PROTOTRACTATUS

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

16

The letter is written in German and can be found in McGuinness et al. (eds), Wittgenstein

Familienbriefe (Wien: Hlder-Pichler-Tempsky, :qq6), p. .. I am grateful to Enzo de Pellegrin

for his help with German.

17

McGuinness, Some Pre-Tractatus Manuscripts (hereafter Manuscripts), repr. in his

Approaches to Wittgenstein (London: Routledge, .oo.), pp. .q6q. McGuinness paper was

originally published under the title Wittgensteins Pre-Tractatus Manuscripts, Grazer Philo-

sophische Studien, / (:q8q), pp. .

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

case for the missing manuscript is more dicult to make: McGuinness

(p. .6) argues with great plausibility that there was no notebook of a char-

acter similar to NB :. during July :q:March :q:6. Still, we cannot

conclude from this that Wittgenstein did not do any new work immediately

after the completion of NB .: as I have already said, his October letter to

Russell strongly suggests the contrary. Wittgenstein reports in the same

letter (Letters, p. :o) that he was making a summary of his work on loose

sheets of paper. Perhaps he also kept the results of his new work on these,

not in a notebook, and destroyed the sheets after he had transcribed their

contents in item () and then in item () with revision.

Also, three considerations give reasons to favour my conjecture. First, PT

pp. .8. form a single section and are not separated by further lines, and

this gives a prima facie ground for the hypothesis that the remarks on them

were copied from a single source rather than from multiple ones.

Secondly, I have suggested that the remarks from NB :. on pp. o. of

PT are intertwined with those that presumably come from Wittgensteins

work immediately following NB .. If this is correct, it would be plausible to

suppose that the original source for pp. o. was a manuscript that already

contained Wittgensteins reorganization of the materials from NB :. by

incorporating them into his work during the subsequent period.

Thirdly, there is evidence on pp. .8. that the remarks from NL and NB

:. have already undergone some revisions. For example, PT .o.6 reads

We understand [a proposition] when we understand its constituents (my

translation). But the original remark in NL was We understand [a proposi-

tion] when we understand its constituents and forms (NL, p. :o; my italics

of course this is Russells English translation of Wittgensteins original

German remark). If we are reminded that what Wittgenstein means by

forms in NL are relation signs, we may read this revision as reecting the

development of his thought that the distinction he had drawn between

names and relation signs in NL collapsed at the time of composing the

immediate source manuscript for pp. .8. of PT.

18

Another example is PT

.o.:, which reads Reality [Wirklichkeit] must be restricted to two alterna-

tives by a proposition: yes or no; to this end it must be completely described

by the proposition (my translation). The original remark in NB, however,

was The meaning [Bedeutung] of a proposition must be restricted to two

alternatives by the proposition and its way of representing: yes or no. To this

end it must be completely described by the proposition (NB, p. ..; my

translation). As is fairly well known, Wittgenstein initially thought in NL that

8 JINHO KANG

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

18

Or we could read this revision as indicating a less signicant change that Wittgenstein no

longer uses the term form to refer to relation signs in PT. I prefer the rst reading, but I

cannot argue for it here.

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

a proposition has meaning as well as sense and that the meaning of a

proposition is a fact that corresponds to it (NL, p. q). The above entry in NB

shows that Wittgenstein still held onto this thought while making the entry.

Later in the Tractatus, however, we nd that he no longer talks about the

meaning of a proposition as something distinct from its sense. It is not hard

to surmise, then, that the change from meaning in the NB entry to reality

in PT .o.: reects this change in Wittgensteins thought. Another inter-

esting feature of PT .o.: is that the phrase and its way of representing

[und seine Darstellungsweise] in the NB original is missing from it, but this

dierence is the result of Wittgensteins crossing out the phrase that

was initially contained in PT .o.:. This strongly suggests that in contrast

with the phrase and its way of representing, the term meaning in the NB

entry had already been replaced with reality in the immediate source manu-

script for PT .o.:. Therefore it further supports my general conjecture

that pp. .8. of PT do not come directly from the missing Norway manu-

script and NB :., but rather from another manuscript which contained

their revision.

I now turn to the next three sections: the rst on pp. .6o, the second on

pp. 6o, and the third on pp. 6o. They contain many remarks from NL

and NB :.; some of the remarks on pp. 6o can also be traced in MN.

Here, however, the order of their appearance hardly follows their order in

these manuscripts. The length of each section is also considerably shorter

than that of pp. .8o. These features suggest that the remarks in these

sections are organized rather thematically, and we can indeed nd a common

theme governing each section. The general subject of all three sections is

logic. It is understandable why Wittgenstein gives a special treatment of this

subject by separating these sections from others, for the clarication of the

nature of logic was without doubt the central task of his early philosophy.

Since these sections do not contain any remarks occurring in NB , I con-

jecture that their immediate source was made by Wittgenstein between the

completion of NB . ( June :q:) and the starting of NB (April :q:6). We

have seen that he was summarizing his previous work during this period; the

three sections from p. . to p. o presumably come from the summary of

Wittgensteins thoughts on logic in NL, MN and NB :..

The section pp. .6o mostly consists of general remarks on the nature of

logic. It begins with Wittgensteins cryptic assertion Logic must take care

of itself (PT .o6.), which originally occurs as his rst philosophical entry

in NB : (NB, p. .). The remark expresses the idea of what I call the autonomy

of logic, which plays a crucial role in shaping the subsequent development of

Wittgensteins thought: among the consequences of the autonomy of logic

are the sign/symbol distinction, the separation of logical syntax from the

ON THE COMPOSITION OF THE PROTOTRACTATUS q

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

meaning of a sign, the limits of language as the limits of the world, and the

impossibility of giving an a priori specication of the logical forms of elemen-

tary propositions.

19

And we can nd in the section pp. .6o that these ideas

are indeed its main themes.

The following two sections on pp. 6o and pp. 6o then deal with the

nature of logical constants and logical propositions, respectively. The section on

pp. 6o discusses truth-functions and quantiers. In particular, Wittgen-

stein explains truth-functions by what he calls the class-theory [Klassen-

Theorie] in NB . (NB, p. ), which characterizes truth-functions in terms of

their roles in the inferential relations among propositions.

20

A discussion

of the identity sign is absent, and this reects Wittgensteins view since

November :q: that the identity sign can be completely eliminated in a

logically perspicuous notation (NB, p. ). The section ends with several

brief remarks on the notion of operation, which is employed by Wittgenstein

in order to explain the nature of truth-functions in the Tractatus. The section

on pp. 6o then discusses the nature of logical propositions, explaining

their tautological character and how it makes them unique when compared

with ordinary non-logical propositions. This part of Wittgensteins early

philosophy is relatively well known, so I shall not comment further.

The section on pp. o: need not concern us much here, for it is very

brief and consists of only four remarks (6.o:, 6.o., 6., ). Perhaps Wittgen-

stein did not derive them from his manuscripts but newly formulated them

while composing PT, which would then explain why he separated this small

section from others.

The next section, which consists of the remarks from p. : to p. 8, is

drawn mainly from NB :., but also from NL, MN and NB , and again it

is organized thematically. The topics treated here are those which Wittgen-

stein has not discussed until p. :: the nature of causality and of scientic

laws; the logical form of propositions containing expressions for proposi-

tional attitudes; the meaning of the world and life; ethics; mysticism; and

probability. In other words, Wittgenstein discusses on pp. :8 what one

might call the side-topics

21

of his early philosophy, or those topics to which

he applies his investigations on logic and the nature of a proposition.

The remarks on pp. 8:o comprise a large single section. Here, we can

nd that those from .:. on p. 8: to ..o. on p. 86 are exclusively drawn

from NB , and again almost exactly in the order of their appearance

:o JINHO KANG

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

19

I discuss the idea of autonomy of logic and the pivotal role it plays in the development of

Wittgensteins thoughts in ch. of my The Road to the Tractatus: a Study of the Development of

Wittgensteins Early Philosophy (Harvard Ph.D. dissertation, .oo).

20

I give an account of Wittgensteins class-theory in ch. of my dissertation.

21

I am not entirely happy with this term, as it suggests that these topics are somehow less

important in the Tractatus. But I have failed to come up with a better alternative.

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

there.

22

With this feature as a clue, I suggest that the section pp. 8:o is

similar to pp. .8., that is, the selection from Wittgensteins manuscripts

roughly in their original order. An examination of the other blocks of the

section gives some plausibility to this proposal. The remarks from .o:. on

p. 8 to .... on p. 8: are concerned with the general form of proposition

and related topics. None of its remarks is in NB :., while the opening

remark, .o:., can be found in NB (NB, p. 8q). It turns out that the rst

series of philosophical remarks in NB addresses just the problem of the

general form of proposition (NB, p. :; I give some discussion of these

remarks in the next section). These circumstances suggest that pp. 88:

originally come from Wittgensteins work following NB . and immediately

preceding NB , the work that presumably led to the subsequent develop-

ment of his thought on the general form of proposition in NB .

What about the block from ..o: on p. 8 to .oo:6 on p. :o? If the

general conjecture I have made is correct, the remarks here must have been

drawn from the manuscript(s) Wittgenstein composed after NB , i.e., after

January :q:. Wittgenstein writes in a postcard to Engelmann on .6 January

:q: that he can work again.

23

He then writes in a letter to Engelmann

(p. ) on : March :q: that he is working reasonably hard. Finally, we nd

from Freges postcard to Wittgenstein on .6 April :q: that Frege is amazed

at Wittgensteins nding the time to do scientic work [wissenschaftlichen

Arbeiten] while in military service.

24

It is unlikely that the work Wittgenstein

was doing at this period was simply that of extracting from what he had

already written; it must have been some new work. Therefore these docu-

ments favour the hypothesis that Wittgenstein was working on new material

in :q: whose manuscript is now missing. Indeed, it turns out that hardly

any remarks on pp. 8:o can be directly traced in NL, MN or NB :.

25

An examination also indicates that several thoughts on these pages are the

results of the development after NB . For example, Wittgenstein declares in

..o: on p. 8 that he separates the concept of generality from truth-

functions, and criticizes Frege and Russell for combining both concepts

in their generality notations; but we do not nd any indication of this idea in

ON THE COMPOSITION OF THE PROTOTRACTATUS ::

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

22

Only two out of the o remarks on pp. 8:6 (6. and 6.) are missing in NB .

Interestingly, these remarks comprise what turns out to be the notorious penultimate passage

of the Tractatus, where Wittgenstein declares that his statements in the Tractatus should even-

tually be recognized as nonsense.

23

Engelmann, Letters from Wittgenstein with a Memoir (Oxford: Blackwell, :q6), p. .

24

Frege, Briefe an Ludwig Wittgenstein aus den Jahren :q::q.o, p. :, ed. A. Janik and

P. Berger, in B. McGuinness and R. Haller (eds), Wittgenstein in Focus Im Brennpunkt Wittgenstein

(Amsterdam: Rodopi, :q8q), pp. .

25

There are only seven traceable remarks out of q8 in this block: 6.: (NB, p. 8:), .o.:

(NL, p. :o6), .:o:: (NB, p. ), .oq:: (NB, p. 6:), .. (NB, p. 8.), 6.. (NB, p. q:), and

..o::. (NB, p. o).

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

NB or in the manuscripts prior to it. Also, Wittgenstein talks substantially

about the nature of mathematics on pp. :oo. (6.o:, 6.., 6.., 6..:, 6...,

6.o::) and, in particular, gives a denition of numbers in terms of indices of

operations (6.o::) which is essentially the same as what appears in Tractatus

6.o.. But apparently he had not yet reached this idea when he completed

NB . Indeed, the nature of mathematics is a topic Wittgenstein seldom

touches up to the period of NB .

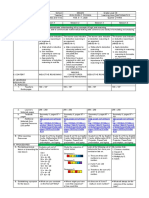

To summarize, I suggest that PT is organized in the following way:

:. pp. .8: Core-PT

.. pp. .8.: from the manuscript containing the revision of NL and

NB :.

(a) pp. .8: from NL

(b) pp. o: from the missing Norway manuscript

(c) pp. o.: from NB :. and the work immediately following NB .

. pp. .6o: the autonomy of logic and its implications

. pp. 6o: the nature of logical constants

. pp. 6o: the nature of logical propositions

6. pp. o:: additional concluding major remarks

. pp. :8: side-topics (science, analysis of judgement, ethics, probability,

etc.)

8. pp. 8:o: from later manuscripts

(a) pp. 88:: from the work immediately preceding NB

(b) pp. 8:6: from NB

(c) pp. 8:o: from the :q: manuscript(s) following NB .

Admittedly, some of the suggestions are highly conjectural. But all seem to

me at least reasonably plausible. My hope is that they can serve as a useful

starting-point for further investigations of PT.

III

I now turn to the date of composition of PT. Von Wright, in his intro-

duction to the reconstructed version of PT (p. q), suggests that PT was

written just before the nal composition of the Tractatus in the summer of

:q:8. The suggestion is primarily based on the occurrence of a dedication to

the memory of David Pinsent on the third page of PT. Pinsent, who was

Wittgensteins closest friend, was killed in an aircraft accident on 8 May

:q:8. Von Wright points out that Wittgenstein could not have known the

news until a month or so later. And we know from Wittgensteins letter to

Russell (Letters, p. :::) that he nished the Tractatus in August :q:8; hence the

:. JINHO KANG

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

conjecture that the composition of PT was immediately prior to that of

the Tractatus.

As von Wright himself (p. q) was aware, his proposal was based on the

assumption that the dedication to the memory of Pinsent had not been

added later to the main body of PT. However, there is a reason to doubt this

assumption. Among the documents we have, there is a letter sent to Witt-

genstein by Ellen Pinsent, David Pinsents mother, in which she informs

Wittgenstein of her sons tragic death. The letter is dated 6 July :q:8, and

it is natural to think that Wittgenstein came to know of Pinsents death

through this letter.

26

We do not know exactly when Wittgenstein received

the letter or when in the August of :q:8 he nished the Tractatus, but it seems

reasonable to suppose that there would have been at most a month left for

Wittgenstein to work on PT and the Tractatus if he had started composing

PT after he received Ellen Pinsents letter. Even if we take into consideration

the circumstance that Wittgenstein was on leave from early July to the end

of September after his long involvement in military service,

27

I nd it hard

to believe that he managed to complete both PT and the Tractatus within a

month. Therefore it seems to me that the dedication to the memory of

Pinsent in PT is indeed a later addition, which undermines the main reason

for accepting von Wrights proposal.

More recently, in the article mentioned in the previous section,

McGuinness has put forward a radically dierent hypothesis (Manuscripts,

pp. .668). He proposes that Wittgenstein worked on PT at three dierent

stages, writing its rst : pages from October :q: to March :q:6, the second

part up to p. 8 around September :q:6, and the third up to p. :o. some

time between January :q: and July :q:8. McGuinness proposal has been

widely accepted among Wittgenstein scholars, and the :qq6 edition of the

reconstructed version of PT now begins with McGuinness preface, where

he reiterates his hypothesis.

28

The proposal, if correct, would have an

important consequence for the study of the origin of the Tractatus. Combin-

ing the three dierent parts of PT with other manuscripts of Wittgensteins,

we would now have a fairly comprehensive list of pre-Tractatus manuscripts

that covers the entire period of his early philosophy: NL (October :q:), MN

(April :q:), NB :. (August :q:June :q:), PT pp. : (October :q:

ON THE COMPOSITION OF THE PROTOTRACTATUS :

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

26

Wittgenstein sends a reply in which he expresses his wish to dedicate the Tractatus to

David Pinsent. Both Ellen Pinsents letter and Wittgensteins reply can be found in von Wright

(ed.), A Portrait of Wittgenstein as a Young Man (Oxford: Blackwell :qqo), pp. :oq. Probably von

Wright did not know of the existence of these letters while writing Introduction in :q:.

27

See McGuinness, Wittgenstein: a Life (University of California Press, :q88), p. .6.

28

Prototractatus, pp. viixii. McGuinness hypothesis can also be found in his introduction to

the German critical edition of the Tractatus. See Logisch-Philosophische Abhandlung: kritische Edition,

ed. B. McGuinness and J. Schulte (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, :q8q), pp. xxiixxiv.

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

March :q:6), NB (April :q:6January :q:), PT pp. :8 (September :q:6),

and PT pp. 8:o. ( January :q:July :q:8). Again, the existence of this

comprehensive list leads us to expect that it would enable us to chronicle

Wittgensteins philosophical developments in his early period and identify

when and how he came up with the various central ideas of the Tractatus.

But is McGuinness proposal right? Obviously, what is most signicant in

his proposal is the conjecture that a large part of PT, its rst : pages, was

already composed during October :q:March :q:6. This conjecture is

based on McGuinness investigation of the list of Wittgensteins manuscripts

set out in the previous section. Item () in the list supposedly contained

the revision of the missing Norway manuscript (which included NL and the

original source of MN) and NB :.. McGuinness claims that item () is none

other than PT in its early form, which he calls proto-Prototractatus,

physically identical with the rst : pages of PT. McGuinness (Manuscripts,

pp. .66) gives three reasons for his claim: rst, he points out that the rst

: pages of PT do largely consist of the remarks from NL, MN and NB :.,

while none of the remarks from NB occurs before p. 6. Secondly, as I

have said, there are several lines inserted in PT, and one of them is on p. :

following what turns out to be the nal remark of the Tractatus (Whereof

one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent). Given the occurrence of this

remark, McGuinness interprets the line on p. : as the seal marking a

provisional closing-point of PT. Thirdly, he argues that the rst : pages

of PT are dierent from what remains, in that there is roughly a natural

progression concerning the numbering of their remarks, those with the

numbers starting with 6 being lled in last, whereas we cannot nd such a

progression in the remaining part of PT.

But these reasons are somewhat tenuous. As for the rst, it is entirely

possible that the remarks from NB are absent on the rst : pages of PT

not because the latter were written before NB , but simply because

Wittgenstein extracted the remarks up to p. : from the manuscripts prior to

NB . In fact, the structure I have discerned in the previous section suggests

that this was precisely the case (with the possible exception of Core-PT; I

shall talk about this shortly). As for the second, there are ve other lines

occurring prior to p. :. If the line on p. : can be interpreted as the seal

separating the remarks prior to it from the rest of PT, why not the previous

ones? McGuinness is simply silent about the occurrence of these lines. As for

the third, I confess that I cannot see such a progression of numbering on

pp. : of PT. Indeed, the existence of a block like pp. .8 seems to

make the supposition dicult to maintain, for the remarks in this block

follow the order of their occurrence in NL; surely this order cannot have

anything to do with that of numbering.

: JINHO KANG

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

So the reasons McGuinness gives do not seem to support his proposal

that the rst : pages of PT were written during October :q:March :q:6.

But my discussion so far has not refuted it, either. That is, McGuinness

proposal is still compatible with what we can plausibly infer from PT and

other relevant documents. Is there any positive reason to think that his

proposal is wrong?

There is one, I think, which comes from an examination of Core-PT. This

comprises pp. .8 of PT, and there is no possibility that it was later added

to the section starting on p. .8, as the latter immediately follows Core-PT

without a change of page. So if McGuinness proposal is correct, Core-

PT must also have been written before NB . If so, the thoughts in Core-PT

must be less developed than those in NB . But it seems to me that several

ideas in it are indeed more fully developed than those in NB .

All these ideas relate to the problem of formulating the general form of

proposition. In Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein recalls through the

mouth of an interlocutor that this problem gave him most headache [meiste

Kopfzerbrechen],

29

and an examination of his manuscripts in the early period

seems to conrm this recollection: though the phrase the general form of

proposition appears as early as MN (MN, pp. :::, ::), Wittgenstein fails to

reach its formulation even at the very end of NB . In his NB entry on .:

November :q:6, for example, he conrms only that the general form of

proposition exists and that it must be possible to formulate it (NB, p. 8q).

Wittgenstein is not yet capable of saying what it is. On the other hand, the

general form of proposition does appear in Core-PT (PT 6),

30

although not

exactly in the same form as in the Tractatus. This already raises a suspicion

for the consequence of McGuinness proposal that Core-PT was composed

before NB .

The general form of proposition Wittgenstein ultimately gives in the

Tractatus is [p, , N( )] (Tractatus 6). He writes in Tractatus . that this

formulation is a variable. Again, he remarks in .: that all variables can be

construed as propositional variables [Satzvariablen], i.e., variables whose values

are (linguistic) propositions and not objects or facts. According to Wittgen-

stein, there are three ways of stipulating values of a propositional variable:

rst, we can simply enumerate those propositions that are its values;

secondly, we can give a function fx whose values for all values of x are the

ON THE COMPOSITION OF THE PROTOTRACTATUS :

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

29

Wittgenstein, Philosophical Investigations, tr. Anscombe, .nd edn (Oxford: Blackwell, :q8),

6.

30

The formulation in PT 6 is dubbed the general form of a truth-function. But

Wittgenstein says in PT that a proposition is a truth-function of elementary proposition,

which makes it clear that the formulation in PT 6 is intended as the general form of

proposition. Wittgenstein also calls the general form of proposition in the Tractatus the general

form of a truth-function (Tractatus 6).

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

propositions to be described (Tractatus .o:); nally, we can give a formal

law that governs the construction of the propositions (ibid.). The pro-

positions resulting from the third kind of stipulation form a formal series

[Formenreihe],

31

its formal law characterizing the formal properties common

to all the propositions thus constructed.

The general form of proposition Wittgenstein gives in Tractatus 6 belongs

to this third way of stipulating its values: its rst term p represents a

collection of elementary propositions. The third term species the operation

applied to an arbitrary term to produce the next term; the operation em-

ployed in the general form of proposition is the operation N, or the

generalized Sheer stroke that simultaneously negates all its bases (Tractatus

.o.). The second term represents arbitrary results of applying the

operation N successively to the elementary propositions represented by p.

What the general form of proposition says, then, is that its value is any term

of a formal series resulting from successive applications of the operation N to

elementary propositions which are independently specied and are repre-

sented by p as the rst term of this series.

So the central idea for Wittgensteins formulation of the general form of

proposition is that of formal series. Now we do nd that the idea of formal

series appears in Core-PT in a fairly developed form. Wittgenstein says that

one of the three ways of stipulating propositions for a propositional variable

is to give certain formal features characterizing those propositions (PT

.oo:, .oo). He also claims that Frege and Russell failed to see the

possibility of this formal kind of generalization (PT .oo:), and thus that

their way of characterizing the ancestral relation contains a vicious circle

(PT .oo:). According to Wittgenstein, the ancestral relation holding

among the propositions aRb; (x):aRx.xRb; (x, y):aRx.xRy.yRb; ... must be

construed as a formal property characterizing the series of these propositions

(PT .oo.). All these remarks appear without any signicant change in

Tractatus .:., .o:.

On the other hand, nothing recognizable as the idea of formal series

occurs in any manuscripts prior to NB , and we can witness only a glimpse of

the idea when Wittgenstein began making the entries of NB in April :q:6

(NB, p. :):

Every simple proposition can be brought into the form x.

That is why we may compose all simple propositions from this form.

Suppose that all simple propositions were given me: then it can simply be asked what

propositions I can construct from them. And these are all propositions and this is how

they are bounded.

:6 JINHO KANG

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

31

Pears and McGuinness translate this term as a series of forms; I have followed Ogdens

translation.

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

(p): p = aRx.xRy. ... .zRb

(p):p = aRx (:6 April :q:6)

The above denition can in its general form only be a rule for a written notation

which has nothing to do with the sense of the signs.

But can there be such a rule?

The denition is only possible if it is itself not a proposition.

In that case a proposition cannot treat of all propositions, while a denition can. (:

April :q:6)

The above denition, however, just does not deal with all propositions, for it

essentially contains real variables. It is quite analogous to an operation whose own

result can be taken as its base. (. April :q:6)

These are rather dark remarks, and I shall not attempt to give a detailed

exegesis of them. What is important for my purpose here, however, is that

the denition of simple propositions Wittgenstein gives in the passage is

very similar to the formal series aRb; (x):aRx.xRb; (x, y):aRx.xRy.yRb; ...

in PT .oo. and again in Tractatus .:., and that he gives the denition

still in terms of a generalized proposition with a quantier ( p) in front of it.

This indicates that Wittgenstein has not yet come up with the idea of pre-

senting the denition of the ancestral relation as a formal law generating a

formal series.

Wittgenstein remarks on the next day that the denition he has given can

only be a rule for a notation and cannot be itself a proposition. It seems to

me that he anticipates here the view in Core-PT and in the Tractatus that a

formal series must be characterized not by a generalized proposition but by

a propositional variable, i.e., a stipulation of propositions, without being

itself a proposition. One might question my conjecture on the ground that a

rule for a mere notation cannot be a stipulation of propositions. I do not think,

however, that Wittgenstein means by a rule for a written notation in the

above passage a rule manipulating meaningless marks or signs in a purely

syntactic sense. When he remarks that such a rule has nothing to do

with the sense of the signs, I take him to mean simply that one need not

know the sense of the signs in order to see what kind of propositions can be

constructed from them by the rule. Even though one does not know the

senses of p and q, for example, one can know that a proposition p q can

be constructed from p and q by the rule for the disjunction. Still, accord-

ing to Wittgenstein such a construction is possible only because p and q are

propositions, i.e., have senses.

On . April :q:6, then, Wittgenstein points out that the denition

contains a real variable and is analogous to an operation. The term

operation appears as early as in NL (NL, p. :o), but this passage is appar-

ently the rst indication of the idea that one way of giving a propositional

variable is to specify a formal law with the help of an operation. Again it

ON THE COMPOSITION OF THE PROTOTRACTATUS :

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

shows that Wittgenstein was only beginning to develop the idea of formal

series by the time he started NB .

Moreover, I have remarked that the operation Wittgenstein employs in

characterizing the general form of proposition in the Tractatus is the opera-

tion N, or the generalized Sheer stroke. The formulation of the general

form of proposition in Core-PT 6 does employ the operation N. On the other

hand, even though NL suggests that Wittgenstein already knew the Sheer

stroke at that time,

32

the idea of the generalized Sheer stroke with an arbitrary

number of bases does not occur in NB or in any manuscripts prior to it.

Perhaps more decisively, on p. : of Core-PT occurs the following explana-

tion of the existential quantier in terms of the operation N:

... If has as its values all the values of a function (x) for all values of x, then N( )

means (x).(x).

This remark in PT .. is repeated almost verbatim in Tractatus ... On the

other hand, we nd Wittgenstein asking the following question in the entry

of NB on :: May :q:6 (NB, p. .)

(x).x

Is (x) etc. really an operation?

But what would be its base?

It is hard to believe that Wittgenstein made this sort of entry after he came

up with the idea in PT ...

I think that the textual considerations I have so far given provide fairly

conclusive evidence against McGuinness conjecture that the rst : pages of

PT were composed before NB . They must have been written after NB ,

some time between January :q: and July :q:8.

Considering the information currently available, any further conjecture

regarding the date of composition of PT will have to be speculative. I shall

give one that seems most plausible to me. I have suggested in my account of

the structure of PT that the remarks on pp. 8:o originate from a :q:

manuscript (or manuscripts) Wittgenstein composed after NB . I have also

suggested that rather than being newly written material, Core-PT is more

likely to be based on a previous manuscript having the character of a

summary of Wittgensteins work. If these suggestions are right, Wittgenstein

must have rst completed the :q: manuscript(s) and the manuscript for

Core-PT before he started PT.

33

He was at the Russian front for the whole of

:q:, serving as an artillery ocer at a division of the Austro-Hungarian

:8 JINHO KANG

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

32

See NL, pp. :o., where Wittgenstein introduces the Sheer stroke of a disjunctive form

(p q).

33

In what follows, my description of Wittgensteins situation in :q::8 is based on the

accounts given by McGuinness, Wittgenstein: a Life, pp. .66, and R. Monk, Wittgenstein: the

Duty of Genius (New York: Free Press, :qqo), pp. :o.

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

IIIrd Army. The army was stationed north of the Carpathian mountains

until July, when the Russians launched the Kerensky oensive. I conjecture

that Wittgenstein worked on the :q: manuscript(s) and the manuscript for

Core-PT during the period JanuaryJuly :q:. The Austro-Hungarian IIIrd

Army made a counter-oensive against the Russians, and advanced along

the river Pruth, ending by capturing the city of Czernowitz in the Ukraine

in August. Wittgenstein was stationed with the Army at Czernowitz until the

end of February :q:8, after which he was transferred to the Italian front.

The situation during Wittgensteins presence at Czernowitz was relatively

quiet and manageable, with few military battles taking place after a limited

advance on . August :q:. My conjecture is that it was during this period

from September :q: to February :q:8 that Wittgenstein composed PT.

34

Engelmann (Introduction, p. q) testies that Wittgenstein dictated his

manuscript for a typewriter before going to the Italian front in March :q:8,

and it is likely that this manuscript was PT itself or the rearrangement of the

remarks in PT according to their numbers. Apparently there were still

problems that remained to be solved, and Wittgensteins work at the Italian

front seems to have been devoted to them. A postcard of June : from Frege

to Wittgenstein suggests that Wittgenstein came up with the nal solutions

by early May :q:8. Frege writes

Many thanks for your card of :o.V. I am pleased that you have arrived at a certain

conclusion. May you soon be able to write down everything you have come up with

so that it shall not be lost. This may help me advance in the dicult area in which I

am struggling.

35

It may have been that Wittgenstein started composing PT around this

time, not in late :q: as I have suggested. But I am somewhat sceptical

about this possibility, for the Austrian oensive took place on June :, about

a month later, and Wittgenstein actively participated in the oensive. This

was the last battle he took part in, and he was given leave on July :q:8

until the end of September. As I have already indicated, Wittgenstein

reports in his letter to Russell that he nished the Tractatus in August :q:8.

He would probably have composed the Tractatus with (the typescript of ) PT

as its basis during JulyAugust of :q:8, renumbering and rearranging the

remarks in PT, adding new ones, polishing various expressions, and

improving styles. Assuming that the remarks on pp. :o.: of the original

ON THE COMPOSITION OF THE PROTOTRACTATUS :q

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

34

This is also Monks conjecture (Wittgenstein: the Duty of Genius, p. :.), although he does not

make clear on what evidence he bases it. In Wittgenstein: a Life (p. .6), McGuinness also

entertains the possibility of Wittgensteins composing PT at the Russian front in :q:. Appar-

ently, however, McGuinness changed his mind later, as shown in his Manuscripts.

35

Frege, Briefe an Ludwig Wittgenstein aus den Jahren :q::q.o, p. :. I have followed

the unpublished translation by Burton Dreben and Juliet Floyd.

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

manuscript of PT were directly incorporated into the Tractatus, I conjecture

that they date from this period.

If my conjecture so far is on the right track, we may conclude that after

all, von Wrights original proposal concerning the date of composition of PT

is more to the point than McGuinness: McGuinness proposal implies that

the rst : pages of PT were completed about two years before Wittgenstein

started composing the Tractatus in its present form, and this naturally en-

courages the idea that there may be some signicant dierence between PT

and the Tractatus that reects the two years development in Wittgensteins

thought.

36

But if Wittgenstein composed PT from late :q: to early :q:8, the

time at which his view must have been developed into its mature form, there

is little reason to think that the thoughts in PT deviate from the Tractatus in

any signicant way. So even though von Wrights specic proposal that PT

was composed in the summer of :q:8 is not convincing, his general char-

acterization of PT as an immediate predecessor of the Tractatus seems to be

entirely apt.

From a dierent perspective, however, we can see that McGuinness pro-

posal is more to the point than von Wrights. McGuinness certainly deserves

credit for rst pointing out the pattern in PT showing that its remarks are

drawn from Wittgensteins manuscripts roughly in their chronological order,

a pattern that is also suggested by my discussion of the PT sections after

Core-PT. Surely Wittgenstein would have made various changes to the

remarks he extracted in accordance with the latest stage of the development

in his thought, but each section of PT must still preserve the main ideas of

the corresponding manuscripts. I thus think that we are still left with the

possibility of using [PT] to elucidate the order in which Wittgenstein intro-

duced into his nal Tractatus ... things new and old, a hope McGuinness

expresses in his article (Manuscripts, p. .6q). In fact, the detailed

correlation I have made of each section of PT with Wittgensteins other

manuscripts seems to reinforce this hope.

37

Harvard University

.o JINHO KANG

The Editors of The Philosophical Quarterly, .oo

36

See, e.g., M. Kremer, Contextualism and Holism in the Early Wittgenstein: from

Prototractatus to Tractatus, Philosophical Topics, . (:qq), pp. 8:.o. Assuming McGuinness

proposal, Kremer argues that some notable changes in the numbering from PT to Tractatus

indicate a fundamental shift in Wittgensteins thought towards contextualism and holism.

37

I would like to thank Warren Goldfarb and Thomas Ricketts for encouraging discussions

and helpful comments, and two anonymous referees for useful suggestions.

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

J

a

n

u

a

r

y

9

,

2

0

1

4

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

p

q

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

You might also like

- The Realistic Spirit Wittgenstein Philosophy and The Mind Representation and MindDocument345 pagesThe Realistic Spirit Wittgenstein Philosophy and The Mind Representation and MindJuan-hito Rocha100% (1)

- Wittgenstein's Remarks On The Foundation of MathematicsDocument25 pagesWittgenstein's Remarks On The Foundation of Mathematicsgravitastic100% (1)

- Nietzsche - Last NotebooksDocument334 pagesNietzsche - Last Notebooksplgomes92% (13)

- A New Edition of Nestle Aland Greek New Testament J Keith ElliottDocument19 pagesA New Edition of Nestle Aland Greek New Testament J Keith ElliottAnonymous cXzO2E750% (4)

- Wittgenstein On Truth and Necessity in Mathematics - Joseph (1994)Document215 pagesWittgenstein On Truth and Necessity in Mathematics - Joseph (1994)Brian WoodNo ratings yet

- Pascal's Treatise On The Arithmetical Triangle: Mathematical Induction, Combinations, The Binomial Theorem and Fermat's TheoremDocument14 pagesPascal's Treatise On The Arithmetical Triangle: Mathematical Induction, Combinations, The Binomial Theorem and Fermat's TheoremYEAG92No ratings yet

- 1994 Vlastos G. - Socratic StudiesDocument166 pages1994 Vlastos G. - Socratic StudiesVildana SelimovicNo ratings yet

- Oxford Referencing Style PDFDocument9 pagesOxford Referencing Style PDFDomestos125100% (2)

- (Lecture Notes in Mathematics 1538) Paul-André Meyer (Auth.) - Quantum Probability For Probabilists-Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg (1995)Document321 pages(Lecture Notes in Mathematics 1538) Paul-André Meyer (Auth.) - Quantum Probability For Probabilists-Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg (1995)panou dimNo ratings yet

- DLL Math 8 4.1Document8 pagesDLL Math 8 4.1Irish Rhea Famodulan100% (1)

- Geometry Chapter 2 PDFDocument113 pagesGeometry Chapter 2 PDFKosin ChuaprarongNo ratings yet

- A New Approach To Quantum Logic PDFDocument194 pagesA New Approach To Quantum Logic PDFBiswajit PaulNo ratings yet

- Klaassen - Wittgenstein As A Kantian PhilosopherDocument21 pagesKlaassen - Wittgenstein As A Kantian Philosopherandersonnakano6724No ratings yet

- Bigtype 1 3 DBDocument8 pagesBigtype 1 3 DBCamila JourdanNo ratings yet

- On The Origin and Compilation of Cause and Effect: Intuitive Awareness'Document8 pagesOn The Origin and Compilation of Cause and Effect: Intuitive Awareness'malachi42No ratings yet

- Barker, 1979 - Untangling The Net Metaphor PDFDocument18 pagesBarker, 1979 - Untangling The Net Metaphor PDFandersonnakano6724No ratings yet

- Wittgenstein on the Arbitrariness of GrammarFrom EverandWittgenstein on the Arbitrariness of GrammarRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (4)