Professional Documents

Culture Documents

'Postscript To Genocide,' by Susan Schulman, Delayed Gratification

'Postscript To Genocide,' by Susan Schulman, Delayed Gratification

Uploaded by

Susan SchulmanOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

'Postscript To Genocide,' by Susan Schulman, Delayed Gratification

'Postscript To Genocide,' by Susan Schulman, Delayed Gratification

Uploaded by

Susan SchulmanCopyright:

Available Formats

Dec

Sun 22nd

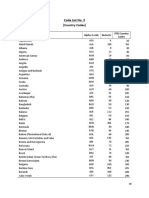

!"#$%%& () *"$"+%&, -.%

%/-*0-$%1 by civilian

helicopters lrom a N

compound in Bor, South

Sudan, leaving an estimated

3,000 loreigners still trapped

in the town by hghting. An

earlier S mission to rescue its

citizens lrom Bor was

abandoned alter its helicopters

were hred upon. Fri 27th

Mon 23rd

Denis MacShane, the lormer

Labour MP and Europe

minister, is ,%&$%&*%1 $2 ,"3

42&$5, "& 6.",2& lor making

lalse expense claims

amounting to almost 913,000.

782 4%49%., 2# :0,,"-&

6.2$%,$ ;.206 <0,,= :"2$

-.% .%>%-,%1 #.24 6.",2&

three months ahead ol

schedule. Nadezhda

Tolokonnikova and Maria

Alyokhina claim the amnesty is

a PP stunt by the Kremlin

ahead ol the Winter Olympics

in Sochi and announce plans

to set up a human rights

organisation.

Tue 24th

A Pussian research ship gets

$.-66%1 "& 5%-/= "*% "&

?&$-.*$"*- 8"$5 @@ *.%8

4%49%., 2& 92-.1A The

Akademik Shokalskiy is stuck

about 1,500 nautical miles

south ol Hobart, Tasmania.

Wed 25th

Pussia 1.26, ->> *5-.;%,

-;-"&,$ $5% ?.*$"* BC, the

28 Greenpeace activists and

two journalists who were

arrested in September when

Pussian authorities boarded

their ship, the Arctic Sunrise.

The group had protested

against a Gazprom oil rig.

A child born today

will grow up with

no conception of

privacy at all

S whistleblower D18-.1

)&281%& 8-.&, -;-"&,$

;2/%.&4%&$ ,6="&; in

Channel 4's annual

Christmas message.

Postscript

to a genocide

On 28th December,

the UNs Force Intervention

Brigade in the Democratic Republic

of the Congo called on the FDLR militia

whose members perpetrated the

Rwandan Genocide in 1994 to put down

their weapons and hand themselves in.

Susan Schulman, who has been

tracking this violent, ruthless group

for the last ve years, tells the story

of their devastating impact on

the local population and of

the armed children who nally

stood up to them

Photography: Susan Schulman

Sat 28th

October 2013

He has gone as far as he can by

road. After six bone-shaking hours

on the heavily potholed dirt track

the motorbike rider deposits him at

the intersection and drives of. He is

alone. He looks at the footpath ahead

of him. He has longed for this moment

since violence engulfed his family

and forced him to ee his birthplace

in the heartland of eastern Congo.

His village, Langira, where I first

met him in 2009, is still a three day

walk away over mountainous terrain.

But for the rst time in almost ve

years, 60-year-old Azayi Kabunga is

going home.

" #$%&' ($#

)*$+) $,, *-) .$#

-& /-0%12 3453

February 2009

The helicopter circles over the densely

forested terrain below, its Ukrainian

pilots peering intently out of the

window, searching for the smoke

signal that will guide us to the landing

pad. The mountains spread out in

all directions as far as the eye can

see. This is eastern Congo. There are

no roads here, no phone reception.

It is accessible only by foot. It is some

of the most deadly terrain on earth.

Conict and insecurity have raged

here for nearly 20 years, as myriad

armed militias and home-grown Mai

Mai (self defence groups) have preyed

on the population, competing for the

regions abundant resources. Five

million lives have been lost in these

forests in two decades, and a million

people displaced. In 1999, the UN

established a peacekeeping mission,

Monusco, here. At 22,000 troops it is

now the worlds largest and longest-

serving UN force.

The area borders Rwanda, and

after the genocide of the Tutsis in

Rwanda in 1994 some of the perpe-

trators, members of the notorious

Hutu Interhamwe, fled into these

dense forests. They never went home.

Instead, they regrouped into a military

and christened themselves the Forces

Dmocratiques de Libration du

Rwanda the FDLR. Heavily armed,

and estimated to number around

4,000, they are the most organised

and deadly of the many armed groups

who live in these forests. Since arriving

in the area, they have used horric

violence murder, torture and rape

against the local population. Not one

family has been left untouched.

But now, at last, hope for peace is in

the air. A groundbreaking agreement

between Congo and Rwanda has just

been concluded, which prioritises

ridding eastern Congo of the FDLR.

Joint military operations against the

FDLR have been launched and we

are en route to the front line of this

efort, the forward operating base of

the Rwandan Defence Force (RDF).

The thin plume of smoke is

spotted. As we begin our descent, a

rough 50 metre-wide circle hacked

out of the dense bush becomes visible.

A gaggle of local Congolese dressed in

rags stand at the edge of the landing

pad as heavy bags are unloaded from

the helicopter. Marked Lady Shoes,

they contain the green wellington

boots favoured by the RDF. The RDF

ofcers are enlisting the assembled

Congolese to help carry the sacks to

their troops deeper in the bush. Its

a rare opportunity for the locals to

earn money, and theres no shortage

of volunteers.

Operations will be conducted on

foot. The soldiers, accompanied by

their chosen porters carrying sacks of

Lady Shoes, le silently into the bush.

The path descends steeply, criss-

crossed by roots, and the thick jungle

enclosing us creates an eerie twilight.

The soldiers move swiftly and it is

hard to stay upright. We cross a small

river, and an ascent brings us out of

the bush and onto a high crest where

we catch our breath.

The path disappears. Feet slip

on the steep hillside. An old porter,

exhausted, barefoot and thin as a rail,

drops his sack and struggles to hoist

its 50 kilo load onto his back. His feet

sink deep into the mud as the younger

porters mock him and the soldiers

shout at him to hurry.

Dusk has fallen by the time we

reach Langira. It is a typical village in

the rural, resource-rich area of North

Kivu where, in the absence of roads,

communications and state presence,

impunity rules. This is where the

thousands who ood the camps for

the displaced many miles away come

from; this is where the GBV (Gender

Based Violence) victims who crowd

the far-away hospitals have been

grievously wounded. This is where

people have struggled to survive since

the FDLR arrived 15 years earlier,

fresh from their butchery in Rwanda.

Dawn has barely broken the next

day when a group of villagers emerges

through the morning fog. They have

been sleeping in the bush in fear

for their lives. One of them, Azayi

Kabunga, 56, shows me around the

village. He is an important man in the

area: a teacher, plantation owner and

leader. His house has a corrugated iron

roof, a sign of uncommon prosperity.

The FDLR have killed a lot of

people, he says, gesturing at the

verdant surroundings. There are

a lot of tombs around here. The

group has murdered eight of Azayis

family members, including his father

and sister.

We pass small houses with peaked

thatch roofs. All are deserted and

empty. Small tufts of green poke

through the mud walls.

The years of relentless violence

have had a catastrophic impact.

Education, healthcare, agriculture,

commerce: all have been decimated,

impoverishing people who had always

lived comfortably and easily from

the produce of their fertile region,

and sending many others to the grim

refuge of distant camps. The ongoing

operations are intended to end the

horror and at long last bring peace.

Hopes are high.

Mortars echo in the hills around

us. The RDF radios crackle. The

commander issues quick-re orders

to his troops. The military operation is

planned to last for a month. It is now

entering its third week.

A few hours later a woman

emerges from the bush, struggling

75% !EF: 5-/%

G">>%1 - >2$ 2#

6%26>%HI ?+-=" ,-=,H

;%,$0."&; -$ $5%

/%.1-&$ ,0..20&1"&;,A

J75%.% -.% - >2$ 2#

$249, -.20&1 5%.%IK

6-771'89) +1.:* 1) 1 *87-:$;.89 71&<) 1. 1& 190# (1)8 $, .*8 =$&'$78)8

,$9:8) &819 /1)*%&'1 >1') 019?8< @A1<# B*$8)C 198 %&7$1<8<

DEF .9$$;) +17? .*9$%'* .*8 980$.8 981:*8) $, G17-?17- <-).9-:.2 +*-:* -)

a|so nhabted by FDLP ghters "H1#- /1(%&'1 -& F8(9%19# 344I

October 2009

I have come to Goma, the main town

in North Kivu. In 1994, thousands of

Rwandan refugees poured over the

border here to escape the genocide

in their country as it unfolded over

a period of 100 days in April. By the

time it ended, 800,000 Rwandans

had been killed and 850,000

Rwandan refugees occupied ve huge

camps set up for them in DRC just

north of Goma. When the refugees

started to return home the camps did

not close. They soon lled again, but

this time with Congolese displaced by

the FDLR.

I am in Mungunga camp, a vast,

hellish terrain of plastic sheeting

shelters set on a bed of sharp lava

rocks. It is a harsh environment.

It begins to rain, and I step into

a shelter. A woman of about 30 sits

inside. A baby clings to her, screaming

inconsolably, and a dazed toddler is

pressed up against her side. Sat on

the bare lava rock oor are two young

boys, both terrifyingly skinny and

utterly devoid of energy. Their knee

joints bulge obscenely, their eyes are

sunk deep in their sockets.

The woman looks at me. I know

you, she says, incredulously. You

were with the Rwandan soldiers in

Langira, lming us just when we had

started to ee.

It is difficult to reconcile this

Eleema with the woman I met nine

months earlier. It is even more difcult

to reconcile her boys, whose vibrant

energy and high spirits had so struck

me then, with the two boys now sat in

front of me, listless and barely able to

keep their eyes open. They had never

intended to come this far.

The FDLR was burning whole

villages, Eleema tells me. After the

RDF left, they started hunting people.

If they found you they would cut your

arms, your legs or pierce your eyes

and leave you blind. They were raping

women they raped you and tied you

to a tree and just left you there. Some

people died because there was no way

we could care for their injuries. We

just had to leave them there and they

bled to death.

Travelling on foot, it took them

three months to make the 100 mile

journey here.

See how the children look. Thats

because theyve been ill for a long

time, without food or medicines.

Looted of their belongings early on,

Eleema and her children never spent

more than two days in one place and

didnt dare eat a cooked meal for fear

the smoke would give them away. You

just had to pull your children by the

arm to keep them going that was the

only way to survive. Many didnt make

it. Eleemas in-laws, grandparents

and brother-in-law were amongst

those killed.

The population of Langira has

also been forced to ee. Azayi and

his family are in Goma too, sharing

a dirt oor with two other displaced

families. Left with nothing to do and

no way to make a living, Azayi has the

air of a defeated man. The operations

launched in February were meant to

bring peace. Not this.

Meanwhile, in Kimua, in Azayi and

Eleemas home area of Walowa-Yunga,

the UN has established a small base

of 30 Uruguayan soldiers. The area is

thick with FDLR, hidden in the dense

forests where they have lived rough for

15 years, The purpose of the base is to

persuade FDLR combatants to leave

the bush and repatriate to Rwanda,

and to protect the civilian population.

Occasional FDLR combatants,

AK-47s slung over their shoulders,

grenades attached to their belts,

pass through on the path which runs

between the hilltop village and the UN

base set in the muddy eld below. They

pause to chat amongst themselves

and, at one point, try unsuccessfully

to persuade the UN soldiers to loan

them their satellite phone. Very

occasionally, a combatant wanting to

be repatriated to Rwanda will arrive in

the dead of night at the base.

Despite his muddy bush home,

FDLR Major Nassor, 40, is wearing

i mpeccabl y pressed fati gues

and gleaming wellington boots when

I meet him at the derelict ruins of a

school, accompanied by a teenage

soldier whose AK-47 hangs over

a green shirt with a gorilla emblem

on it. The teenager is as inarticulate

and unhappy as Major Nassor

is garrulous.

Handsome, cocky and vain, Major

Nassor scofs at the idea that RDF and

UN operations are having any impact

on the FDLR. He not only denies any

abuses against the locals, but also

declares they are all friends. The

Congolese population testies to our

friendship! he exclaims.

I have yet to meet a Congolese

who will testify to anything of the sort.

Certainly not the man who arrived at

the UN base with his head split and

bleeding from an FDLR attack that

had happened just 500 metres from

where we were sitting, nor the woman

with the terrified baby screaming

on her shoulders who also arrived at

the base after being attacked nearby.

Nor the many hiding in terror in the

bush from the FDLR, like Kabeti

Boulenbe Mputo and his family, for

whom the arrival of the UN brings

hope from the relentless violence of

their friends.

Kabeti is a local chief and school

teacher in the nearby village of

Mukoberwa. He has come from

his bush refuge to the main path to

meet the UN patrol. At last the UN

has come. Now we can be saved,

he declares.

Azayi greets her. Her name is Eleema

Nbandu.

The refugees soon move on,

disappearing back into the bush. A

small girl, ve or six years old, wearing

a ragged dress and with a small fabric

sack hanging from her forehead

pauses on the edge of the clearing,

staring at me. She has never seen

anyone like me before. The last white

person to have come here was decades

earlier, a missionary in the 1960s.

I ask her if she thinks I am the

only white person in the world or if

she thinks there are others. Ha! I

know there are others, she exclaims

triumphantly. They live in the

helicopters and airplanes. And

with that, she runs of to catch up

with the others.

against the weight of the sack hung

from her forehead. Close behind

comes a steady stream of people

carrying all manner of belongings

mattresses, sewing machines, pots and

pans, goats, chickens. One small child

cradles a white guinea pig; the woman

behind her balances a teetering stack

of schoolbooks on her head. These

are refugees from the neighbouring

community of Brazza. They are eeing

the horror of the FDLR.

The convoy pauses for a while: a

guitar is strummed, children cavort

and, in this brief moment of respite,

an almost carnivalesque spirit sets

in. A woman passes the infant on her

shoulders to her older daughter, and

puts her sack onto the ground, as

her small sons run off to play.

L-&1,24%H

*2*G= -&1 /-"&H

M-N2. O-,,2. ,*2##,

-$ $5% "1%- $5-$ :E!

-&1 (O 26%.-$"2&,

-.% 5-/"&; -&= "46-*$

2& $5% !EF:K

J78801 1&< *89 ,10-7# -& 344I FEAD K1L$9 M1))$9 V||agers from Brazza approach Langra as they ee FDLP atroctes

November 2010

It is almost two years since the launch

of operations to defeat the FDLR. The

little UN base at Kimua has doubled

in size to 60 troops. Azayi and Eleema

are still in Goma. Their circumstances

have gone from bad to worse. But

the FDLR has gone from strength

to strength. They have become the

undisputed rulers of the area, a fact

acknowledged by the UN.

Captain Pasayero is in charge of

the Uruguayan Monusco troops. We

are on the hill overlooking the eld

and the UN base. Some two dozen

heavily armed men are below. They

sway about, crack jokes and play with

their weapons. They look drunk.

The local law and the power in

this area is in the hands of the FDLR,

Captain Pasayero remarks, surveying

the scene below. More armed men

are approaching, crossing the field

directly in front of the UN base. All

those men are FDLR. All of them.

They control who goes where. They

control everything.

The FDLR are no longer living

in the bush. They have appropriated

all the locals houses over the 20

kilometre stretch regularly patrolled

by the UN. Their heavily armed

presence is ubiquitous, inescapable

and shocking. Villages and paths are

overowing with armed, intimidating

and often drunk combatants. The

army operations and the UN were

meant to eliminate the FDLR. Instead,

the UN has presided over a stunning

expansion of FDLR power.

Their brutal regime has made

prisoners of the locals on their own

land. The FDLR are charging road

tax, controlling the markets, and

cultivating the appropriated elds of

the population, starving the locals.

They have revived the health clinic,

press-ganged the local doctor to treat

them and have even installed their

own tailor. They rape, loot, kill and

terrorise at will, uninhibited by the

UN presence.

But something new is happening.

For the rst time since I have been

coming here, a mood of resistance

is sweeping the area. The story of a

young man who had responded to

FDLR violence at the market by taking

an axe to a militia mans head echoes

in proud hushed tones through every

village; the stuf of legend, inspiration

and hope.

Locals have well and truly had

enough. If we leave it to the UN, 15-

year-old schoolboy Amani explains,

we risk being exterminated. Amani

and his friend Vianey have come to

talk to me in the privacy of the UN

base to explain why they are forming

their own Mai Mai group.

There are too many atrocities.

There was a woman that they raped,

and after raping her they destroyed

her eyes. My own mother was raped.

We cant just stand there with folded

arms any more, Vianey declares.

We have to protect our population.

Amani, who wears a small oval amulet

containing a picture of Obama, nods

his assent. We are many now, and not

only schoolboys, Vianey asserts.

However many they might be,

they have no weapons. Instead,

they rely on finding or scrounging

cartridges which they throw onto the

re to trick the FDLR into believing

they are armed.

A hundred miles away I find

Eleema in a shack in the corner of

an overgrown, deserted lot in Goma.

Her previous shelter washed away

in the rain. A man took pity on her,

homeless with five small children,

and has allowed her to stay in the

shack, which was never meant for

habitation. Eleema has just delivered

a baby, Esther. It was the middle of

the night and rain was pouring in

through the roof, as usual, forming a

pool in the middle of the dirt oor. The

older children were stood shivering,

pressed up against the walls, as

Eleema laboured before she tells me

with shame delivering her baby in

the puddle.

Azayi, too, is despondent. Unable

to find any work, he is relying on

what his wife is able to earn carrying

heavy loads which, at 55 years old,

she is barely able to manage. His son

Daniel, 12, is being thrown out of

school almost every day for not having

paid the fees and is nding it hard

to cope.

There are two main feelings I

have, Azayi condes. First is shame.

Second is anger. I am ashamed to see

my son kicked out of school because I

am unable to full my duty of paying

the fees Now I have to be here like

a beggar, waiting for my wife to come

back so that I can be fed. Waiting for

the children to be chased, not having

any solution to provide, to save them

from being expelled.

If I heard the FDLR were no

longer in Langira, I wouldnt even

take the time to pack, I would just

rush back, Azayi says. But, for now, it

is impossible.

N& 34542 .*8 FEAD *1) 0$O8< -&.$ .*8 /-0%1 98'-$& 1&< *1) .1?8& :$&.9$7P Q*8-9 1908< ;98)8&:8 -) %(-R%-.$%)

5ST#819T$7< ):*$$7($# "01&- Heav|y armed FDLP ghters have decded

to sett|e n the area permanent|y. They have approprated homes, e|ds, and

*19O8).) J78801 1&< *89 :*-7<98& *1O8 0$O8< -&.$ 1 )*1:?

July 2012

Kimua is almost unrecognisable. The

UN base has relocated to the peak of

a hill and it is now surrounded by the

plastic sheeting of countless close-

ly-packed shelters which descend all

the way down the slope.

When I was last here in November

2010, heavily armed FDLR militia

were everywhere. Armed males still

abound. But they are not FDLR. They

are all locals.

A year and a half earlier, schoolboys

Vianey and Amani began their defence

of the community by trying to trick the

FDLR into believing they were armed.

Now there is no shortage of weapons.

They call themselves the Force for the

Defense of Congo (FDC) one of the

DRCs newest Mai Mai groups and

claim to number 500. They have been

organised under the command of a

former ofcer of the Congolese armed

forces, and longtime Mai Mai veteran,

General Ambroise Bwira, who hails

from the nearby village of Buhimba.

There was a failure, General

Bwira tells me, his white tracksuit

gleaming in the sun. The UN mission

didnt succeed. So it was necessary for

the civilian population to take charge.

Some of his warriors are wearing

rafa skirts and bizarre headdresses,

some look no more than 13 years

old. All believe in the invincible

power conferred upon them by their

ancestors. You cant touch it nor

can you see it, Bwira explains. It is

a super metaphysical power. Through

this power, nothing can resist us.

Regardless of the arms of the FDLR,

and even their bombs, they cannot

resist us.

Two young boys, both heavily

armed, one wearing a closely trimmed

mohawk hair style, hurry past me.

Nearby, a teenager is loading pellets

into an empty gun cartridge. Although

the FDC is strongly backed by the

community, little children ee when

they see their armed elders approach,

disappearing so they are not forced to

carry water for them.

For the rst time in years, there

are no FDLR to be seen anywhere.

Major Nassor has been killed.

But the success has come at a cost.

Many young soldiers from this small

community have already been killed

in the ghting. All the homes for 20

kilometres around have been burned

or abandoned. Whole communities

have simply ceased to exist. More

than a thousand people have

been forced to seek refuge in the

makeshift shelters under the local UN

base. The atmosphere has been

transformed from village to military

camp. And the armed boys have

changed. Parents are worried.

People look over their shoulders

before talking. Schoolteacher Baeni

Rumbo will only speak in the privacy

of the UN base. He shakes his head

sadly: When a boy carries a gun, he

is no longer the same person. He is

someone else. The soldier who has a

gun is not a friend of the population.

Hes 50 percent for the population

and 50 percent military. Even if its

my own child.

While you might not be able

to see the FDLR now, they are still

there. They have only retreated to

the surrounding bush. As military

operations continue, everyone in

the community is painfully aware

of the risk to their youth. But they

need to believe the FDC will succeed.

They see their children with guns as

their saviours.

The failure of the government

and United Nations to vanquish

the FDLR has led to the arming of

schoolboys. Eight months later, in

March 2013, the UN closes its base

in Kimua and withdraws, leaving

the children of the FDC to deal with

the FDLR alone.

October 2013

Azayis long-awaited return home

left him dismayed. Emerging into

Langira he found a profoundly altered

atmosphere. My generation is no

longer there, he explains. The young

FDC combatants, the same local boys

who saved the area from the FDLR,

now dominate the villages. They

have diferent priorities. They only

want to live luxurious lives. They sit

around drinking alcohol. When you

suggest they go to work, they think it

is old-fashioned.

They are armed, bored and

spoiling for a ght. It was tense, says

Azayi. People fear someone with a

gun. He feels he has power over you.

Even if that person is your son, your

neighbour, your saviour.

Azayi could only stay a week before

the poisonous atmosphere forced him

back to his half-life in Goma. It wasnt

what he had planned. As long as they

keep their guns, it will be a problem.

I will not go back if they keep their

guns, he adds sadly.

In May 2013, General Carlos

Alberto dos Santos Cruz assumed the

position of Monusco force commander,

along with a new, more muscular

mandate. In November he helped

in the defeat of the rebellion known

as M23 (Mouvement du 23 Mars),

and is now focusing on defeating the

FDLR and the Ugandan Islamist ADF

in the north, the priorities laid out

by the UN security council. But his

newly strengthened remit extends to

all errant militias, including the FDC.

They all need to surrender and return

to normal life, he tells me. But if they

dont agree, we will use all our armed

forces against all armed groups.

The government has issued a call

to the myriad groups of armed Mai Mai

combatants in the area to lay down

their arms and be integrated into the

Congolese military. Eight thousand

combatants have flocked to the

reintegration camps. General Bwira,

accompanied only by his escorts and

leaving his FDC combatants behind, is

amongst them.

But the ofer of integration is swiftly

turning sour. With no negotiations or

communication with the government,

impatience amongst the combatants

is mounting. General Bwira is furious.

We came because we wanted peace,

he tells me. We thought it was a good

deal. His eyes glint ominously. I cant

predict what might happen but just

imagine. I was a big chief controlling

my people and now in the camp they

treat me like a dog? Like a mosquito?

We are very angry.

If the integration fails, General

Bwira will pick up his weapon and

return to his young FDC combatants

in Langira and the other villages of the

area. They will cease to be defenders

and instead will become violent

predators, as can be expected of the

other 8,000 combatants.

Some ghters have already lost

patience and returned to the bush.

Reports of insecurity are on the rise.

Another cycle of displaced people is

beginning to arrive at the camps.

There is a very real risk that

Azayi, Eleema and others from their

area may simply have swapped one

menace, the FDLR, for a new,

homegrown one. They stand on the

brink of a new struggle, this time with

the enemy within.

?+-=" *20>1 2&>=

,$-= - 8%%G

9%#2.% $5% 62",2&20,

-$42,65%.% #2.*%1

5"4 9-*G $2 5", 5->#P

>"#% "& Q24-A R$ 8-,&I$

85-$ 5% 5-1 6>-&&%1K

FDC ch|d ghters re|ax at a footba|| match wth ther weapons An FDC so|der wearng the rafa outt whch represents the nvncb|e

;$+89 $, .*8-9 1&:8).$9) An FDC ghter wth hs weapon

You might also like

- Consuming the Congo: War and Conflict Minerals in the World's Deadliest PlaceFrom EverandConsuming the Congo: War and Conflict Minerals in the World's Deadliest PlaceNo ratings yet

- Demonic Males - Richard WranghamDocument368 pagesDemonic Males - Richard WranghamQuan100% (8)

- Lit Assessment 2Document2 pagesLit Assessment 2atiqa100% (3)

- United Nations Security Council - Background GuideDocument10 pagesUnited Nations Security Council - Background GuideAhaan MohanNo ratings yet

- Living On The Edge of A KnifeDocument1 pageLiving On The Edge of A KnifeHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- Salaam DarfurDocument4 pagesSalaam DarfurHeidi KingstoneNo ratings yet

- Rwanda 25 Years OnDocument12 pagesRwanda 25 Years OnBarrie CollinsNo ratings yet

- The Anthropologist, the Waterfall and the Very Worried SangomaFrom EverandThe Anthropologist, the Waterfall and the Very Worried SangomaNo ratings yet

- Voiceofpeace Issue8 201401-EnDocument10 pagesVoiceofpeace Issue8 201401-Enapi-223749841No ratings yet

- Tantalika FinalDocument159 pagesTantalika Finalnontobekosibanda62No ratings yet

- Dying to Live: A Rwandan Family's Five-Year Flight Across the CongoFrom EverandDying to Live: A Rwandan Family's Five-Year Flight Across the CongoNo ratings yet

- LITERATUREDocument11 pagesLITERATUREJay MadridanoNo ratings yet

- LRA - Human Rights Watch ReportDocument72 pagesLRA - Human Rights Watch ReportBlake ParkerNo ratings yet

- Chapter Two AyomDocument15 pagesChapter Two AyomAbedism JosephNo ratings yet

- Inherited First DraftDocument135 pagesInherited First DraftRob HendricksonNo ratings yet

- Word Format - Statement From H.E The President On The Kasese Adf AttackDocument5 pagesWord Format - Statement From H.E The President On The Kasese Adf AttackMasuumi JumaNo ratings yet

- Pol Sci NotesDocument13 pagesPol Sci Notesred gynNo ratings yet

- History of Lawaan Eastern Samar by Crispin G. GavanDocument28 pagesHistory of Lawaan Eastern Samar by Crispin G. GavanDr. Ramon Leo Gavan100% (5)

- Anuak Politics, Ecology, and The Origins of Shilluk Kingship PDFDocument13 pagesAnuak Politics, Ecology, and The Origins of Shilluk Kingship PDFMaria Martha SarmientoNo ratings yet

- The Teeth May Smile but the Heart Does Not Forget: Murder and Memory in UgandaFrom EverandThe Teeth May Smile but the Heart Does Not Forget: Murder and Memory in UgandaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- Tammarin's Guide To The WorldDocument11 pagesTammarin's Guide To The WorldDawn SmithNo ratings yet

- 24-07-11 War Over But Massacres Continue in Ivory CoastDocument17 pages24-07-11 War Over But Massacres Continue in Ivory CoastWilliam J GreenbergNo ratings yet

- Test Bank For Middle East 14Th Edition Lust 1506329284 9781506329284 Full Chapter PDFDocument24 pagesTest Bank For Middle East 14Th Edition Lust 1506329284 9781506329284 Full Chapter PDFgladys.johnson538100% (11)

- In the Kingdom of Gorillas: The Quest to Save Rwanda's Mountain GorillasFrom EverandIn the Kingdom of Gorillas: The Quest to Save Rwanda's Mountain GorillasRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (10)

- The Tendrils of Shadow By: Jordan Prato Chapter 1: The Begginging Present.Document7 pagesThe Tendrils of Shadow By: Jordan Prato Chapter 1: The Begginging Present.Jordan PratoNo ratings yet

- Shantytown AnalysisDocument11 pagesShantytown Analysisphumlanim633No ratings yet

- Midsummer Gitnang Tag-Araw Beginning: Sarah Mae R. IsmaelDocument7 pagesMidsummer Gitnang Tag-Araw Beginning: Sarah Mae R. IsmaelSarah Jik-ismNo ratings yet

- From Rebel-Held Congo To Beer Can PDFDocument4 pagesFrom Rebel-Held Congo To Beer Can PDFDaniel CNo ratings yet

- RVI Usalama Project - 8 BanyamulengeDocument65 pagesRVI Usalama Project - 8 BanyamulengeLaIncognitaNo ratings yet

- African AdventureDocument3 pagesAfrican AdventuresusangeibNo ratings yet

- A Cry From The ValleyDocument26 pagesA Cry From The ValleyShahid MehmoodNo ratings yet

- Transcript: Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC DR Phil Clark The School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS)Document1 pageTranscript: Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC DR Phil Clark The School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS)Clara Martinez PoloNo ratings yet

- SwatDocument191 pagesSwatElora TribedyNo ratings yet

- Comprehending Genocide The Case of RwandaDocument22 pagesComprehending Genocide The Case of RwandaakabangalondonNo ratings yet

- LRA War JstorDocument5 pagesLRA War JstorDeanNo ratings yet

- Terra: Our 100-Million-Year-Old Ecosystem--and the Threats That Now Put It at RiskFrom EverandTerra: Our 100-Million-Year-Old Ecosystem--and the Threats That Now Put It at RiskRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Pwee 28Document12 pagesPwee 28Dral BrogoNo ratings yet

- Pwee 27Document12 pagesPwee 27Dral BrogoNo ratings yet

- Manhattan to Baghdad: Despatches from the frontline in the War on TerrorFrom EverandManhattan to Baghdad: Despatches from the frontline in the War on TerrorNo ratings yet

- Sandford 2016Document21 pagesSandford 2016mirojul hudaNo ratings yet

- Lamar Milledge ElementaryDocument4 pagesLamar Milledge ElementaryJeremy TurnageNo ratings yet

- Soc 101 Class ExamDocument10 pagesSoc 101 Class Examgaius014No ratings yet

- Unfinished RevolutionDocument26 pagesUnfinished RevolutionAlex UyNo ratings yet

- Activism: PhilanthropyDocument4 pagesActivism: PhilanthropycorreoftNo ratings yet

- Assignment No. 3 (100 PTS)Document2 pagesAssignment No. 3 (100 PTS)Ken SannNo ratings yet

- EO FirecrackerDocument4 pagesEO FirecrackerVinvin EsoenNo ratings yet

- Ruth B PhilipsDocument26 pagesRuth B PhilipsMorpheus AndersonNo ratings yet

- WHLP Week 1-2, Q1 JBVDocument3 pagesWHLP Week 1-2, Q1 JBVJENNIFER BALMESNo ratings yet

- On The Third Front: The Soviet Museum and Its Public During The Cultural RevolutionDocument18 pagesOn The Third Front: The Soviet Museum and Its Public During The Cultural RevolutionmadzoskiNo ratings yet

- Announcement - Secure MI Pet Sum 734507 7Document6 pagesAnnouncement - Secure MI Pet Sum 734507 7CassidyNo ratings yet

- The Laugher by Heinrich BöllDocument8 pagesThe Laugher by Heinrich BöllMH MoscowNo ratings yet

- GE 2 Corazon Aquino SpeechDocument11 pagesGE 2 Corazon Aquino SpeechAlyssa BihagNo ratings yet

- B Partnership StatementDocument3 pagesB Partnership StatementVasile CatalinNo ratings yet

- Week 17 UcspDocument2 pagesWeek 17 UcspAbram John Cabrales AlontagaNo ratings yet

- Political Science MADocument25 pagesPolitical Science MASelim Bari BarbhuiyaNo ratings yet

- Danish Gold CoastDocument4 pagesDanish Gold Coastemmanuelboakyeagyemang23No ratings yet

- Tsiskari 2021 N1Document86 pagesTsiskari 2021 N1Orange ORNo ratings yet

- JKJJDocument3 pagesJKJJChaterineNo ratings yet

- EVANS v. BOMBARDIER, INC. Et Al ComplaintDocument19 pagesEVANS v. BOMBARDIER, INC. Et Al ComplaintbombardierwatchNo ratings yet

- Naranjo Vs BiomedicaDocument1 pageNaranjo Vs Biomedicapja_14100% (1)

- Cold War Culture in Asian Spies FilmsDocument22 pagesCold War Culture in Asian Spies FilmsAnil MishraNo ratings yet

- The Commonwealth of The PhilippinesDocument7 pagesThe Commonwealth of The PhilippinesRenalyn de LimaNo ratings yet

- Women's Safety LawsDocument40 pagesWomen's Safety Lawskhadija sajda khanamNo ratings yet

- CONSOLIDATED Journal of Proceedings 2nd Regular Session 1 11 24Document20 pagesCONSOLIDATED Journal of Proceedings 2nd Regular Session 1 11 24Mark HenryNo ratings yet

- Labour Cess Clarification ENCPHDocument2 pagesLabour Cess Clarification ENCPHthummadharaniNo ratings yet

- Gender Representation in English TextbooksDocument9 pagesGender Representation in English TextbooksDr Irfan Ahmed RindNo ratings yet

- Lim VS. HMR Phils. Inc. DigestDocument3 pagesLim VS. HMR Phils. Inc. DigestKriziaItao100% (1)