Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Alberto Gonzales Files - Sentencing Typepad Com-Berman Assessing After Booker

Alberto Gonzales Files - Sentencing Typepad Com-Berman Assessing After Booker

Uploaded by

politixOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Alberto Gonzales Files - Sentencing Typepad Com-Berman Assessing After Booker

Alberto Gonzales Files - Sentencing Typepad Com-Berman Assessing After Booker

Uploaded by

politixCopyright:

Available Formats

01.FSR.17.5._291-294.

qxd 9/14/05 4:52 PM Page 291

EDITOR’S OBSERVATIONS

Assessing Federal Sentencing After Booker

DOUGLAS A. BERMAN

FSR Editor; Professor of Law at The Ohio State University Moritz College of Law

“Ours, of course, is not the last word: The ball now lies in Congress’ court. The National Legislature is

equipped to devise and install, long-term, the sentencing system, compatible with the Constitution, that

Congress judges best for the federal system of justice.”

— Justice Breyer, writing for the Court in United States v. Booker

“If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.”

— Proverb

The origins, rationale, and meaning of the Supreme Court’s decision in United States v. Booker1 are

all fascinating topics worthy of extended examination and analysis. But, for federal policy makers and

practitioners (not to mention federal defendants), the most pressing concern is the impact of Booker

on the current realities and future direction of the federal sentencing system. This Issue of FSR

examines the state of federal sentencing after Booker and gives particular attention to whether, when,

and how Congress should respond to Booker. Justice Breyer stressed in the remedial portion of the

Court’s Booker opinion that Congress could choose to redesign the federal sentencing system in the

wake of Booker. But an old proverb, which says “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it,” perhaps counsels cau-

tion as Congress contemplates any “Booker fix.”

As this Issue goes to press, the federal sentencing system has now had over six months to assess

and adjust to Booker’s unexpected remedy for “curing” the federal sentencing guidelines of the Sixth

Amendment problems with judicial fact-finding identified in Apprendi v. New Jersey2 and Blakely v.

Washington.3 The article and extensive primary materials in this Issue highlight that it is now possi-

ble to identify the basic contours of federal sentencing after Booker, but they also suggest it may still

be too early to reach firm conclusions about the current state and future development of federal sen-

tencing policy and practice. The items in this Issue reveal that an initial challenge for policy makers

and practitioners is to assess whether and how the post-Booker federal sentencing system may be

broken in order to be able, in turn, to assess what sort of legislative fix might be needed.

I. Viewing Booker in a Broader Federal Sentencing Context

Though the remedy adopted by the Supreme Court in Booker changed the federal sentencing guide-

lines from mandates to advice, the decision may not have radically transformed essential federal

sentencing dynamics. Indeed, in testimony presented at a hearing convened by a House of Repre-

sentatives subcommittee a month after the Booker decision, U.S. Sentencing Commission Chair

Judge Ricardo Hinojosa stressed that Booker did not alter many central features of the federal sen-

tencing system. In his testimony, which is reprinted in this Issue, Judge Hinojosa highlighted the

central role of the guidelines and the Commission even after Booker, and he explained that the Com-

mission believed sentencing courts should still be giving “substantial weight to the Federal

Sentencing Guidelines in determining the appropriate sentence to impose.”

Similarly, the thoughtful article in this Issue authored by the Honorable James Carr, Chief Judge

of the U.S. District Court of the Northern District of Ohio, sets forth a dozen insights that collectively

Federal Sentencing Reporter, Vol. 17, No. 5, pp. 291–294, ISSN 1053-9867 electronic ISSN 1533-8363

©2005 Vera Institute of Justice. All rights reserved. Please direct requests for permission to photocopy

or reproduce article content through the University of California Press’s Rights and Permissions website at

www.ucpress.edu/journals/rights.htm.

FEDERAL SENTENCING REPORTER • V O L . 1 7 , N O. 5 • JUNE 2005 291

01.FSR.17.5._291-294.qxd 9/14/05 4:52 PM Page 292

suggest that post-Booker sentencing may not be too different from pre-Booker sentencing. Chief

Judge Carr details why the influence and impact of prosecutors and appellate courts ensures that the

new sentencing discretion Booker gives to district judges likely will not dramatically alter the day-to-

day realities of the federal sentencing system.

But Chief Judge Carr’s article also explains why pre-Booker sentencing should not be the gold

standard for assessing the federal system after Booker. Noting the imbalance resulting from unregu-

lated prosecutorial power within a mandatory guideline system, Chief Judge Carr celebrates the fact

that “Booker has restored discretion [to judges that] is regulated, reviewable, and restricted.” In his

words: “Since Booker, we have balance and control. Before we had neither.”

These sentiments are echoed in post-Booker work of the Constitution Project’s Sentencing Initia-

tive and the Blakely Task Force of the American Bar Association’s Criminal Justice Section. The

Constitution Project’s Sentencing Initiative, a bipartisan, blue-ribbon committee created after the

Supreme Court’s decision in Blakely, released in June what it calls “Principles for the Design and

Reform of Sentencing Systems.” Reprinted in this Issue, these aspirational principles for criminal

sentencing systems in the United States include a statement of “several serious deficiencies” in “the

federal sentencing guidelines as applied prior to United States v. Booker.” Notably, these principles

champion a judge-centered sentencing guidelines system, managed by a sentencing commission

and regulated by appellate review, that seems in perfect harmony with the basic themes and specific

mandates in Justice Breyer’s remedial opinion for the Court in Booker.

Similarly, the Blakely Task Force of the ABA’s Criminal Justice Section seems quite keen on the

new federal sentencing world created by the Booker decision. The ABA Task Force Report, which is

reprinted in this Issue, asserts that “Booker yields an innovative mix of sentencing procedures that

may yield excellent results [through its] salutary balance between rule and discretion.” This report

also contends that the “advisory remedy crafted in Booker may well prove as good as or even better

than the mandatory guidelines in achieving the original objectives of the Sentencing Reform Act.”

The ABA Task Force urges Congress to allow the current advisory system to remain in place for at

least twelve months to allow sufficient time to evaluate its efficacy; it also states that if advisory guide-

lines appear unacceptable after this period of study, then Congress should consider developing a

simplified federal sentencing system that complies with the jury trial rights identified in Blakely.

Of course, the Booker remedy has not received praise from all quarters. In testimony presented at

the House hearing right after the Booker decision, Assistant Attorney General Christopher Wray sug-

gested that there would be a “need for legislative action” in response to Booker. Wray’s testimony,

which is reprinted in this Issue, identified “vulnerabilities that are inherent in advisory guidelines,”

and he emphasized concerns about the potential for greater sentencing disparity in the wake of

Booker. Wray also spotlighted a distinct and important concern for the Justice Department, namely

that an advisory guideline system might result in “reduced incentive for defendants to enter early

plea agreements or cooperation agreements with the government.”

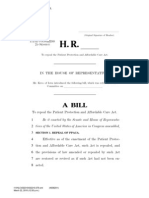

II. Considering Proposed Legislative Responses to Booker

Though most early reactions to Booker were cautious and seemed to adopt a wait-and-see philosophy,

proposals for specific legislative responses eventually emerged. The most surprising and provocative

proposal appeared as a sudden add-on to a House drug sentencing bill, H.R. 1528, entitled “Defend-

ing America’s Most Vulnerable: Safe Access to Drug Treatment and Child Protection Act of 2005.”

Right before a scheduled hearing in April on the main provisions of this bill, a new elaborate section

12 was tacked on with provisions that would essentially forbid judicial consideration of nearly all mit-

igating factors as a basis for sentencing below guideline ranges. Section 12 also proposed significant

procedural restrictions on any possible remaining grounds for downward departure from the guide-

lines (except for departures based on a prosecutor’s motion for an early plea agreement or

substantial assistance in the prosecution of others).

The broad and far-reaching provisions of section 12 of H.R. 1528, which are reprinted in this

Issue, generated potent criticisms. Many institutions and individuals identified problems and imbal-

ances that this proposed response to Booker would engender, and in this Issue we reprint three of the

many letters sent to Congress that assailed the basic approach and specific provisions of section 12 of

H.R. 1528. These three letters, from Professor Frank Bowman and the Committee on Criminal Law

of the U.S. Judicial Conference and federal public defenders, provide an extensive array of legal, pol-

icy, and practical reasons why section 12’s response to Booker could profoundly harm the operation of

the federal sentencing system. Significantly, the negative reaction to section 12 and other provisions

292 FEDERAL SENTENCING REPORTER • V O L . 1 7 , N O. 5 • JUNE 2005

01.FSR.17.5._291-294.qxd 9/14/05 4:52 PM Page 293

of H.R. 1528 seemed to have some impact: the bill received only limited support in the House sub-

committee that first considered it, and months later the bill is still stalled in the House and no

corresponding legislation is under consideration in the Senate.

Though the proposed legislative response to Booker found in section 12 of H.R. 1528 seems now

to have limited support, the Justice Department in June decided to begin advocating its own legisla-

tive response to Booker. In a major policy speech delivered to a conference of the National Center for

Victims of Crime, Attorney General Alberto Gonzales discussed the impact of Booker on federal sen-

tencing and asserted that the “advisory guidelines system we currently have can and must be

improved.” In his speech, which is reprinted in this Issue, Gonzales provided anecdotal accounts of

problems created by Booker, and he claimed that, since Booker, there has been “an increased disparity

in sentences, and a drift toward lesser sentences.” He closed his speech by saying that he favored

“the construction of a minimum guideline system”:

Under such a system, the sentencing court would be bound by the guidelines minimum, just as it

was before the Booker decision. The guidelines maximum, however, would remain advisory, and

the court would be bound to consider it, but not bound to adhere to it, just as it is today under

Booker.

The general reaction to Gonzales’s suggested response to Booker, perhaps because it was set forth

in tentative terms and without proposed legislative language, was somewhat muted. Still, a number

of newspaper editorials, echoing growing criticisms of harsh mandatory minimum sentencing

statutes, spoke out against the idea of creating a “minimum guideline system.” And, shortly after the

Gonzales speech, the National Association of Criminal Defense Lawyers completed a lengthy report

entitled “Truth in Sentencing? The Gonzales Cases.” The report, which is reprinted in this Issue,

examined in depth four specific cases that Gonzales cited as evidence that a legislative response to

Booker was needed. The NACDL report, after its analysis of these four cases, concluded that none of

them “reflects a failure of the judiciary or of the sentencing system.”

III. Examining the Data and Charting a Measured Response

The speech by Attorney General Gonzales highlights that it is dangerously easy to focus post-Booker

analysis on a few specific cases. And, because headline-making cases have always had unique pur-

chase in the development of sentencing laws and policies, the intense scrutiny of post-Booker

developments presents a unique risk that anecdotes and rhetoric will unduly shape debates over the

future development of the federal sentencing system. One post-Booker challenge for those concerned

about the future of the federal sentencing system, and especially for the U.S. Sentencing Commis-

sion, is to ensure that policy makers appreciate (1) that in a huge federal system, with thousands of

sentencings every month, there will inevitably be a few questionable decisions, and (2) that no defini-

tive conclusions should be drawn, or broad legislation enacted, based on a few anecdotal accounts

and sound-bite critiques of post-Booker realities.

To its great credit, in the wake of Booker, the U.S. Sentencing Commission has been taking an

active role in the public dialogue over the current state and the future direction of federal sentencing,

particularly through its regular dissemination of “real-time” post-Booker sentencing data. Nearly

every month, the Commission has reported on post-Booker sentencings in an effort to ensure that

cumulative sentencing data play an integral and effective role in the debate over whether and how

Congress should respond to Booker.

In this Issue, we reprint a small portion of the data that the Commission released concerning the

first six months of district court sentencing after Booker. Though there are many stories to be drawn

from this sentencing data, it is hard to reach any firm conclusions about exactly what all the post-

Booker data means. Because average and median sentence lengths seem stable after Booker, it is hard

to find a lot of support for the contention made by Attorney General Gonzales that we are experienc-

ing a “drift toward lesser sentences.” And yet, because there are more sentences below the guidelines

now than there were before Booker, the overall sentence length data could reflect a change in the mix

of cases masking a genuine shift in the sentencing decisions of district judges. Notably, the Commis-

sion’s circuit-by-circuit post-Booker data perhaps do support Gonzales’s concern that after Booker we

are seeing “increased disparity in sentences.” And yet, significant circuit-by-circuit differences in

departure rates were common before Booker, and different rates of prosecutor departure motions

have also always had a role in geographical variations in the application of the guidelines. Though

FEDERAL SENTENCING REPORTER • V O L . 1 7 , N O. 5 • JUNE 2005 293

01.FSR.17.5._291-294.qxd 9/14/05 4:52 PM Page 294

the Commission’s post-Booker data suggest that the Booker decision has not—at least not yet—pro-

duced a radical change in federal sentencing outcomes, a lot more data and analysis are needed

before even this tentative conclusion can be reached with real confidence.

Ultimately, the sentencing data combines with all the sentencing insights and commentary in

this Issue to highlight that the U.S. Sentencing Commission has a critical role and unique respon-

sibilities in the analysis and development of the federal sentencing system in the wake of Booker.

The Sentencing Commission is the only institution that, by virtue of its information and perspec-

tive, can take a truly comprehensive and balanced view of the entire federal sentencing landscape.

The remarkable remedy that the Supreme Court devised in Booker presents a remarkable opportu-

nity for the federal courts to develop a frequently discussed, but historically elusive, common law of

sentencing. But only the Sentencing Commission will be able to examine and assess the develop-

ment of this common law with an eye on cumulative sentencing data to determine whether the

central goals of federal sentencing reform are being served in the operation of an advisory guideline

system.

Consequently, not only should the Commission continue to assemble and make publicly available

post-Booker sentencing data, but it should also produce reports that explore the pros and cons of vari-

ous potential short-term and long-term responses to Booker. Through such reports, the Commission

can help frame and shape Congress’s examination of the post-Booker world and possible legislative

action. Encouragingly, the Sentencing Commission’s recent statement of priorities, which is

reprinted in this Issue, details that the Commission is focused on continuing “its work with the con-

gressional, executive, and judicial branches of the government and other interested parties on

appropriate responses to United States v. Booker.” In addition, the Commission says it is planning “a

report on the effects of Booker on federal sentencing, including an analysis of sentencing data col-

lected within the first year of that decision.”

In the end, it would seem quite wise for both Congress and the Sentencing Commission to con-

tinue to hold off making substantial changes to the federal sentencing system, at least until the

Supreme Court’s post-Blakely jurisprudence has settled down. Even though Booker clarified the legal

meaning and impact of Blakely for the federal sentencing system, any effort to significantly alter the

structure of federal sentencing remains legally treacherous and fraught with doctrinal uncertainty.

After Booker, it is still difficult to make major structural changes to the guidelines with any constitu-

tional confidence because of the continued uncertainty that surrounds Harris v. United States,4 which

now allows judges to find facts that establish minimum sentences, and Almendarez-Torres v. United

States,5 which now allows judges to find “prior conviction” facts that enhance sentences. (Notably,

the uncertain precedents of Harris and Almendarez-Torres, both of which were 5-4 rulings are made

even more uncertain by the ongoing transitions in the composition of the Supreme Court.) And,

beyond fundamental constitutional concerns, a host of complicated, challenging, and possibly

unforeseen transition issues would likely accompany any major structural changes to the federal sen-

tencing guidelines.

In other words, any significant and far-reaching legislative Booker fix would further disrupt a fed-

eral sentencing system that has just been through a year of considerable turmoil following the

Supreme Court’s Blakely ruling. Because the current post-Booker federal sentencing world is not so

obviously broken, perhaps the old adage counsels against any dramatic fix-it effort. Instead, policy

makers in Congress and the Commission should appreciate that, at least in the short term, a pro-

gram of careful study and cautious consideration of modulated incremental changes, if any changes

are deemed needed at all, is likely to provide the soundest course for the post-Booker development of

the federal sentencing system.

Notes

1

125 S. Ct. 738 (2005).

2

530 U.S. 466 (2000).

3

124 S. Ct. 2531 (2004).

4

536 U.S. 545 (2002).

5

523 U.S. 224 (1998).

294 FEDERAL SENTENCING REPORTER • V O L . 1 7 , N O. 5 • JUNE 2005

You might also like

- High CourtDocument114 pagesHigh CourtZerohedge JanitorNo ratings yet

- Liberty Title IX LawsuitDocument44 pagesLiberty Title IX LawsuitPat ThomasNo ratings yet

- Administrative Law in Context, 2nd Edition - Part33Document15 pagesAdministrative Law in Context, 2nd Edition - Part33spammermcspewsonNo ratings yet

- CP - Courts - Michigan7 2020 BFHPRDocument128 pagesCP - Courts - Michigan7 2020 BFHPRIan Mackey-PiccoloNo ratings yet

- Perry V Schwarzenegger - Vol-13-6-16-10Document164 pagesPerry V Schwarzenegger - Vol-13-6-16-10towleroadNo ratings yet

- 2018 Rabuya's Pre-Week Lecture and TipsDocument15 pages2018 Rabuya's Pre-Week Lecture and TipsAnonymous 5k7iGyNo ratings yet

- Alberto Gonzales Files - 01 fsr18 2 79-83 QXD Sentencing Typepad Com-182 Ed ObsDocument5 pagesAlberto Gonzales Files - 01 fsr18 2 79-83 QXD Sentencing Typepad Com-182 Ed ObspolitixNo ratings yet

- Beyond The "Heartland": Sentencing Under The Advisory Federal GuidelinesDocument27 pagesBeyond The "Heartland": Sentencing Under The Advisory Federal GuidelinesPaul J. HoferNo ratings yet

- States v. Booker On Federal SentencingDocument19 pagesStates v. Booker On Federal SentencinglosangelesNo ratings yet

- Alberto Gonzales Files - 2 15 2005 - Us Sentencing Commission Public Hearing Ussc Gov-Berman Testimony (2-15)Document14 pagesAlberto Gonzales Files - 2 15 2005 - Us Sentencing Commission Public Hearing Ussc Gov-Berman Testimony (2-15)politixNo ratings yet

- Concepcion v. United StatesDocument28 pagesConcepcion v. United Statesdhruv sharmaNo ratings yet

- Garry D. Lloyd v. United States, 407 F.3d 608, 3rd Cir. (2005)Document9 pagesGarry D. Lloyd v. United States, 407 F.3d 608, 3rd Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- CJIS 5201 Module 2 RPDocument7 pagesCJIS 5201 Module 2 RPdhawkins01No ratings yet

- Making Constitutional SenseDocument31 pagesMaking Constitutional SenseStacy Liong BloggerAccountNo ratings yet

- Maximo Langer - Rethinking Plea BargainingDocument78 pagesMaximo Langer - Rethinking Plea BargainingJuan M. MontielNo ratings yet

- United States v. Lata, 415 F.3d 107, 1st Cir. (2005)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Lata, 415 F.3d 107, 1st Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- The Modern Common Law of CrimeDocument94 pagesThe Modern Common Law of CrimeToyNo ratings yet

- Evidence Legislation and Rules - PETER KACHAMADocument37 pagesEvidence Legislation and Rules - PETER KACHAMAPETGET GENERAL CONSULTING GROUPNo ratings yet

- Wilkins v. United States, No. 21-1164 (U.S. Mar, 28, 2023)Document24 pagesWilkins v. United States, No. 21-1164 (U.S. Mar, 28, 2023)RHTNo ratings yet

- "Collegium System For Appointment of Judges'': Submitted To: Dr. Pratyush Kaushik Assistant ProfessorDocument19 pages"Collegium System For Appointment of Judges'': Submitted To: Dr. Pratyush Kaushik Assistant ProfessorKeshav SharmaNo ratings yet

- Law: Essays in Honour of David Mullan (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006)Document30 pagesLaw: Essays in Honour of David Mullan (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2006)Amit SinghNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitDocument37 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Preston v. Ferrer, 552 U.S. 346 (2008)Document21 pagesPreston v. Ferrer, 552 U.S. 346 (2008)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Constitutional LawDocument14 pagesConstitutional LawNathan BreedloveNo ratings yet

- SUBJECT: Constitutional Law TOPIC: Origin of Judicial Review Submitted ToDocument16 pagesSUBJECT: Constitutional Law TOPIC: Origin of Judicial Review Submitted Tomohd waris khanNo ratings yet

- Judge Amy Coney Barrett On Statutory InterpretationDocument8 pagesJudge Amy Coney Barrett On Statutory InterpretationjacoboboiNo ratings yet

- BILDER - The Corporate Origins of Judicial ReviewDocument66 pagesBILDER - The Corporate Origins of Judicial ReviewVinícius Naguti ResendeNo ratings yet

- Bobby Ray Kines v. John Day, 754 F.2d 28, 1st Cir. (1985)Document5 pagesBobby Ray Kines v. John Day, 754 F.2d 28, 1st Cir. (1985)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 132.7.blackhawk Qwcsmtc7Document99 pages132.7.blackhawk Qwcsmtc7AASUGENo ratings yet

- LegalDocument26 pagesLegalDon JohnNo ratings yet

- Retheorizing The Presumption Against ImpDocument55 pagesRetheorizing The Presumption Against ImpAdora Amparo AlcanceNo ratings yet

- Anu Chapter 5Document30 pagesAnu Chapter 5Charu MathiNo ratings yet

- The Constitution Outside The ConstitutionDocument66 pagesThe Constitution Outside The ConstitutionstenioleaoNo ratings yet

- Judicial Amendment To The ConstitutionDocument31 pagesJudicial Amendment To The ConstitutionHardik TwitterNo ratings yet

- Sentencing Class NotesDocument3 pagesSentencing Class NotesChrisNo ratings yet

- United States v. Shamblin, 4th Cir. (2005)Document8 pagesUnited States v. Shamblin, 4th Cir. (2005)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Stare DecisisDocument4 pagesStare Decisismina villamorNo ratings yet

- Building Officials & Code Adm. v. Code Technology, Inc., 628 F.2d 730, 1st Cir. (1980)Document9 pagesBuilding Officials & Code Adm. v. Code Technology, Inc., 628 F.2d 730, 1st Cir. (1980)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Letter To Mr. Crow - May 26, 2023Document7 pagesLetter To Mr. Crow - May 26, 2023Marcus GilmerNo ratings yet

- T-Death PenaltyDocument131 pagesT-Death PenaltyTruman ConnorNo ratings yet

- Peugh v. United States, 133 S. Ct. 2072 (2013)Document38 pagesPeugh v. United States, 133 S. Ct. 2072 (2013)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Congressional Oversight Over JudgesDocument30 pagesCongressional Oversight Over JudgesMarch ElleneNo ratings yet

- United States v. Jimenez-Beltre, 440 F.3d 514, 1st Cir. (2006)Document22 pagesUnited States v. Jimenez-Beltre, 440 F.3d 514, 1st Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Powell RELIGIOUS ORIGINALISMDocument52 pagesPowell RELIGIOUS ORIGINALISMkatesydavisNo ratings yet

- Article: Ntroduction Omparative Ivil Rocedure EnerallyDocument32 pagesArticle: Ntroduction Omparative Ivil Rocedure EnerallyshakeelNo ratings yet

- United States v. Roylin Fairclough, 439 F.3d 76, 2d Cir. (2006)Document6 pagesUnited States v. Roylin Fairclough, 439 F.3d 76, 2d Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- 52 Uchil Rev 751Document23 pages52 Uchil Rev 751Author LeeNo ratings yet

- Bator 1963Document89 pagesBator 1963Alexandru V. CuccuNo ratings yet

- Justice and Legal ReasoningDocument27 pagesJustice and Legal ReasoningmartinsskylarNo ratings yet

- United States v. Clark, 4th Cir. (2006)Document10 pagesUnited States v. Clark, 4th Cir. (2006)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Judicial Review of Political QuestionDocument15 pagesJudicial Review of Political QuestionIlampariNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court of The United States: Cuomo, Attorney General of New York V. Clearing House Association, L. L. C.Document3 pagesSupreme Court of The United States: Cuomo, Attorney General of New York V. Clearing House Association, L. L. C.charlesulysessfarleyNo ratings yet

- American Bar Association Standards For Criminal Justice - PrescripDocument14 pagesAmerican Bar Association Standards For Criminal Justice - PrescripWayne LundNo ratings yet

- Why Judges Must Make LawDocument32 pagesWhy Judges Must Make LawMayuresh DalviNo ratings yet

- Why Judges Must Make LawDocument32 pagesWhy Judges Must Make LawMITIN RUKBONo ratings yet

- Dead or Alive? Comparison of Breyer and Scalia's Constitutional JurisprudenceDocument11 pagesDead or Alive? Comparison of Breyer and Scalia's Constitutional JurisprudenceBronson FordNo ratings yet

- Caso Bobbi Vs BiesDocument3 pagesCaso Bobbi Vs BiesCristian Fabian Gelves DazaNo ratings yet

- Law of Evidence in The United States of America - An IntroductionDocument7 pagesLaw of Evidence in The United States of America - An IntroductionPrabhat GauravNo ratings yet

- Schauer CommonLawLaw 1989Document18 pagesSchauer CommonLawLaw 1989Moe FoeNo ratings yet

- Assignment3 1002 (Jury)Document2 pagesAssignment3 1002 (Jury)rbecky1221No ratings yet

- OMB Guidance Agency Use 3rd Party Websites AppsDocument9 pagesOMB Guidance Agency Use 3rd Party Websites AppsAlex HowardNo ratings yet

- Preliminary Inquiry Into The Matter of Senator John EnsignDocument75 pagesPreliminary Inquiry Into The Matter of Senator John EnsignpolitixNo ratings yet

- Symbolic ObamaCare "Repeal" Bill by Rep. Steve King (R-IA)Document1 pageSymbolic ObamaCare "Repeal" Bill by Rep. Steve King (R-IA)politixNo ratings yet

- ElenaKagan PublicQuestionnaireDocument202 pagesElenaKagan PublicQuestionnairefrajam79No ratings yet

- Volume 10 Pages 2331 - 2583 UNITEDDocument254 pagesVolume 10 Pages 2331 - 2583 UNITEDG-A-YNo ratings yet

- America's Healthy Future Act of 2009Document223 pagesAmerica's Healthy Future Act of 2009KFFHealthNewsNo ratings yet

- Republican PrezDocument72 pagesRepublican PrezZerohedgeNo ratings yet

- DOJ Memorandum: Status of Certain OLC Opinions Issued in The Aftermath of The Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001Document11 pagesDOJ Memorandum: Status of Certain OLC Opinions Issued in The Aftermath of The Terrorist Attacks of September 11, 2001politix100% (10)

- Blagojevich ComplaintDocument78 pagesBlagojevich ComplaintWashington Post Investigations100% (56)

- 1 in The United States District Court For The District of MarylandDocument57 pages1 in The United States District Court For The District of Marylandpolitix100% (3)

- Plaintiff,: in The United States District Court For The Southern District of Alabama Northern Division Bethany KarrDocument16 pagesPlaintiff,: in The United States District Court For The Southern District of Alabama Northern Division Bethany Karrpolitix100% (1)

- Webcast Feedback Form 071907Document1 pageWebcast Feedback Form 071907politixNo ratings yet

- The Electoral College: How It WorksDocument15 pagesThe Electoral College: How It Workspolitix100% (7)

- JTXT9001099898 Nalsar Unhcr Public Intl Law Moot 02 2021 TM Rajnarayanverma004 Gmailcom 20220408 223015 1 21Document21 pagesJTXT9001099898 Nalsar Unhcr Public Intl Law Moot 02 2021 TM Rajnarayanverma004 Gmailcom 20220408 223015 1 21Vicky VermaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 213687Document10 pagesG.R. No. 213687Denzel BrownNo ratings yet

- Regulatory 1Document2 pagesRegulatory 1Junho ChaNo ratings yet

- Santiago V COADocument10 pagesSantiago V COAkresnieanneNo ratings yet

- Unit - IVDocument36 pagesUnit - IVMaria Monisha DNo ratings yet

- Bank United - Motion To Strike Affidavit of Lori SilerDocument5 pagesBank United - Motion To Strike Affidavit of Lori SilerLecso1964No ratings yet

- KARLO ANGELO DABALOS Y SAN DIEGO VDocument22 pagesKARLO ANGELO DABALOS Y SAN DIEGO VAnonymous 659sMW8No ratings yet

- Sanyo vs. Canizares Digest & FulltextDocument9 pagesSanyo vs. Canizares Digest & FulltextBernie Cabang PringaseNo ratings yet

- PBTC V Odom - PeraltaDocument2 pagesPBTC V Odom - PeraltaTrixie PeraltaNo ratings yet

- Inset 2019Document2 pagesInset 2019reiya100% (1)

- Case Digest - Rem 2Document23 pagesCase Digest - Rem 2Stephen Humiwat100% (1)

- CANON 2 RULE 12.03: Republic of The Philippines Manila en BancDocument25 pagesCANON 2 RULE 12.03: Republic of The Philippines Manila en BancJenifer PaglinawanNo ratings yet

- Poche v. Joubran, 10th Cir. (2010)Document12 pagesPoche v. Joubran, 10th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Statutes Affecting The CrownDocument14 pagesStatutes Affecting The CrownDeepashree MNo ratings yet

- Remedies Rules OutlineDocument22 pagesRemedies Rules OutlineRonnie Barcena Jr.No ratings yet

- Rule of Law Under UK ConstitutionDocument11 pagesRule of Law Under UK ConstitutionSheikhadnan advNo ratings yet

- Milagros Ibardovs, Pelagia Nava V CADocument1 pageMilagros Ibardovs, Pelagia Nava V CA123abc456defNo ratings yet

- Cathrine Lagodgod - Case Digests IIDocument37 pagesCathrine Lagodgod - Case Digests IICate LagodgodNo ratings yet

- Rajendra Kumar Saxena vs. Earth Gracia Builcon PVT LTDDocument2 pagesRajendra Kumar Saxena vs. Earth Gracia Builcon PVT LTDsonu mehthaNo ratings yet

- Klapakis EuDocument2 pagesKlapakis EuBlogalNo ratings yet

- What Is Acceleration ??Document4 pagesWhat Is Acceleration ??INFO CENTRE100% (1)

- SEC v. Ralston Purina Co., 346 U.S. 119 (1953)Document6 pagesSEC v. Ralston Purina Co., 346 U.S. 119 (1953)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- CASE ANALYSIS - Group5Document13 pagesCASE ANALYSIS - Group5MohitNo ratings yet

- Data Privacy ActDocument8 pagesData Privacy ActPat QuiaoitNo ratings yet

- United States v. Jennings, 4th Cir. (2010)Document5 pagesUnited States v. Jennings, 4th Cir. (2010)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Unit 4 Classification of LawDocument4 pagesUnit 4 Classification of LawTuAnhNo ratings yet

- Sample ProclamationDocument2 pagesSample ProclamationgellietanNo ratings yet

- (BALIGOD) Tablarin vs. Judge Gutierrez, 152 SCRA 730Document1 page(BALIGOD) Tablarin vs. Judge Gutierrez, 152 SCRA 730LeyardNo ratings yet