Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Perio 2008 04 s0251

Perio 2008 04 s0251

Uploaded by

ChieAstutiaribOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Perio 2008 04 s0251

Perio 2008 04 s0251

Uploaded by

ChieAstutiaribCopyright:

Available Formats

C

o

pyr

i

g

h

t

b

y

N

o

t

f o

r

Q

u

i

n

t

e

s

s

en

c

e

N

o

t

f

o

r

P

u

b

l

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

PERIO 2008;5(4):251258

251 CLINICAL REPORT

Background and aim: Aggressive periodontitis is a critical disease with a poor prognosis for long-term

tooth preservation. Extractions of several hopeless teeth are often necessary with subsequent exten-

sive prosthetic reconstruction. The authors aimed to determine whether or not the preservation of

hopeless teeth can stabilise periodontal conditions over time.

Case report: A 32-year-old female was first examined in the authors department in 1993 with the

diagnosis of generalised severe aggressive periodontitis. Her external treatment plan included several

tooth extractions, bone augmentations, implants, and an extensive prosthetic reconstruction. In accor-

dance with the patients choice, all hopeless teeth were preserved. Non-surgical treatment was per-

formed on all teeth, surgical treatment was performed on teeth without regenerative potential and

with pockets over 6 mm, and surgical regenerative treatment with non-bioresorbable expanded poly-

tetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) membranes was performed on sites with regenerative potential. After sur-

gical therapy, supportive treatment was carried out four times a year to date. Due to the teeth preser-

vation treatments, no prosthetic treatment was necessary, but a gingiva mask was used for the wide

exposed roots of the maxillary anterior teeth.

Results and conclusions: This case shows that periodontal stabilisation and long-term preservation of

even hopeless teeth is possible. The radiographic re-evaluation in 2007 showed bone gain at sites

treated with ePTFE membranes and small bone gain or stabilisation of the bone level in all other treated

sites. The treatment increased the bone level of the hopeless teeth and these teeth have been pre-

served for 14 years.

Matthias Pelka, Anselm Petschelt

Therapy of hopeless teeth a case of long-term

tooth preservation in a patient with generalised

aggressive periodontitis

aggressive periodontitis, hopeless tooth, tooth preservation

Matthias Pelka,

DMD, Priv-Doz Dr

Anselm Petschelt,

DMD, Prof Dr

both at:

Dental Clinic 1

Operative Dentistry and

Periodontology

University Erlangen

Nuremberg, Germany

Correspondence to:

Matthias Pelka

Dental Clinic 1

Operative Dentistry and

Periodontology

University Erlangen,

Nuremberg

Glckstrasse 11,

D-91054 Erlangen, Germany

Tel: +499131 8536310

Fax: +499131 8533603

Email:

pelka@dent.uni-erlangen.de

Introduction

Aggressive periodontitis is considered a multi-fac-

torial disease, comprising a heterogeneous group

of infectious diseases characterised by a complex

hostmicrobial interaction in the periodontal liga-

ment

1

. Aggressive periodontitis (formerly referred

to as rapid progressive periodontitis) often occurs

in people under 35 years.

The aggressive nature of this disease, the early

onset, and the high yearly bone loss confer a high

risk for early tooth loss

2

.

KEY WORDS

C

o

pyr

i

g

h

t

b

y

N

o

t

f o

r

Q

u

i

n

t

e

s

s

en

c

e

N

o

t

f

o

r

P

u

b

l

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

Aggressive periodontitis commonly leads to a

rapid loss of attachment and of adjacent supporting

bone. Although it can affect young, otherwise

healthy individuals, this disease is often associated

with severe congenital defects of haematological

origin, alterations in neutrophil chemotaxis, and sys-

temic conditions, including metabolic disorders

3-8

.

The disease is classified by whether it begins

before or after puberty. Immune deficiencies and a

genetic link have been identified as contributing fac-

tors for all types of aggressive periodontitis

3,8,9

. Indi-

viduals with generalised severe aggressive periodon-

titis are at high risk for tooth loss

10

.

The combination of tooth loss and advanced

bone defects is problematic for subsequent pros-

thetic rehabilitation; the absence of sufficient bone

makes implant therapy difficult, and long teeth result

in poor aesthetics. The patients are often under 30

years old and conventional crown and fixed dental

prosthesis (FDP) reconstructions cause damage to

the predominantly unfilled, intact, neighbouring

teeth. In addition, prosthetic rehabilitations for

patients with severe aggressive periodontitis are

seldom satisfactory. Therefore, the primary goal of

systematic periodontal therapy in young patients

with aggressive periodontitis should be to preserve

the affected teeth for as long as possible.

Case presentation and

phase I therapy

This clinical study describes a female patient with

generalised severe aggressive periodontitis. The

patient first came to the authors clinic at the age of

32 in 1993. Prior to 1993, the disease progression

had led to extensive horizontal bone loss in the max-

illary teeth and several intrabony defects in the pre-

molar and molar regions (Figs 2 and 4). The patient

had been referred with an external treatment plan for

implant and prosthetic therapy with estimated costs

of about 30,000.

Figures 1 to 5 show the clinical and radiographic

records of the patient before treatment (1993) and

14 years later (2007). The maxillary anterior teeth

had sustained extremely advanced bone loss up to

the apical region (Fig 2), indicated clinically by high

tooth mobility. To stabilise the maxillary anterior

teeth, an adhesive composite splint was immediately

applied.

PERIO 2008;5(4):251258

252 Pelka/Petschelt Therapy of hopeless teeth

Fig 1a to d Clinical

frontal views of the

patient: (a) periodontal

treatment began in

1993, (b) 1996 image

shows the same patient

3 years after non-surgi-

cal and surgical therapy.

Recessions of about 4 to

5mm occurred at the

upper front teeth, and

the same patient 6 (c)

and 14 years (d) after

treatment with no

remarkable changes.

a b

c d

C

o

pyr

i

g

h

t

b

y

N

o

t

f o

r

Q

u

i

n

t

e

s

s

en

c

e

N

o

t

f

o

r

P

u

b

l

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

PERIO 2008;5(4):251258

253 Pelka/Petschelt Therapy of hopeless teeth

Fig 2 Radiograph com-

parison of the maxilla in

1993 and 2007. The

main difference is the

clear cortical bone layer

visible in 2007. Slight

regenerations of about

1 or 2mm of bone gain

are visible in the maxil-

lary anterior teeth.

Fig 4 Radiograph com-

parison of the mandible

in 1993 and 2007. The

main difference is the

compact demarcating

bone layer in 2007.

Slight regenerations of

about 2 to 4mm of

bone gain at sites with

intrabony defects were

observed after the

regenerative surgical

procedure.

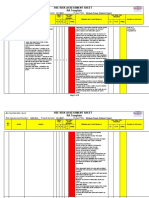

Fig 3 Clinical para-

meters (maxilla): prob-

ing pocket depth (PPD),

bleeding on probing

(BOP) and recessions

(REZ) observed in 1993

(1) and 2007 (2). In

2007 no pockets over

5mm were observed,

and bleeding was found

only at isolated sites.

C

o

pyr

i

g

h

t

b

y

N

o

t

f o

r

Q

u

i

n

t

e

s

s

en

c

e

N

o

t

f

o

r

P

u

b

l

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

Wide interdental spaces within the maxilla and

mandible were clinically conspicuous. In the radi-

ographs, teeth that were missing proximal contact

showed advanced periodontal attachment and bone

loss. Intrabony defects were found at teeth 14, 26,

36, 34, 32, 44, 45, and 46 with localised bone loss

(up to 90% of the root length). Disease progression

led to horizontal bone defects at teeth 12, 11, 21, 22,

23, 41, and 42. According to Machtei et al, teeth

with bone loss at either of the proximal sites of more

than 70% of the bone height were considered hope-

less

11

. These included teeth 12, 11, 21, 22, 34, 44,

and 45.

Due to the high number of intrabony defects, the

advanced state of periodontal disease, and the age

of the female patient, the condition was diagnosed

as rapid progressive periodontitis (currently known as

generalised severe aggressive periodontitis).

At the first visit to the authors clinic in 1993, the

known facts about the disease and disease progres-

sion were explained to the patient, and it was pointed

out that the possibility of preserving the maxillary an-

terior teeth was unlikely due to the advanced bone

loss and high tooth mobility. The treatment modali-

ties, including non-surgical phase I therapy, re-eval-

uation, tooth extractions, and surgical regenerative

phase-II-therapy, followed by implant and prosthet-

ic therapies were explained to the patient. Despite

the low chance of success, the patient wished to try

to preserve the maxillary anterior teeth due to the

high costs of implants and prosthetic reconstruction.

A decision was made to try to preserve the maxillary

anterior teeth if the patient complied with intensive

oral prophylaxis and personal oral hygiene. The ini-

tial sulcus bleeding and proximal plaque indices were

high, about 80% each. Due to the lack of a commer-

cial test for periodontal pathogens at that time, it was

not attempted to identify the specific periodontal

pathogens involved.

The phase I treatment consisted of intensive

quadrant-wise subgingival scaling and root planing

(four appointments) without local anaesthesia. At

the same time, the patient was instructed in intensive

oral care, including basic brushing for 4 minutes three

times a day to completely clean all tooth surfaces,

and special brushing once a day using different sized

brushes to clean the proximal spaces. During the

phase I treatment, the proximal plaque decreased to

45% and the bleeding index decreased to 30%. An

antibiotic treatment was not performed during the

non-surgical phase I treatment, because at that time

the treatment regime did not include antibiotic treat-

ments (except in combination with surgical regener-

ative treatments using periodontal membranes).

Phase II treatment

The authors planned to perform surgical treatments

after a healing phase of 6 weeks. The decision

depended on the improvements gained with oral

hygiene (reductions were found in approximal plaque

index [API] to be 18% and sulcus bleeding index

[SBI] to 5%) and the regenerative potential for each

surgical site. The primary aim was to improve the peri-

odontal situation in sites with intrabony defects. In

PERIO 2008;5(4):251258

254 Pelka/Petschelt Therapy of hopeless teeth

Fig 5 Clinical para-

meters (mandible):

probing pocket depth

(PPD), bleeding on

probing (BOP), and

recessions (REZ) in 1993

(1) and 2007 (2). In

2007, pockets were

found at two sites that

were deeper than 5 mm

with localised bleeding.

C

o

pyr

i

g

h

t

b

y

N

o

t

f o

r

Q

u

i

n

t

e

s

s

en

c

e

N

o

t

f

o

r

P

u

b

l

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

the lower left and right sextants, the authors planned

two surgical procedures (over 3 months) using non-

bioresorbable expanded polytetrafluoroethylene

(ePTFE) membranes (GoreTex, WL Gore & Associ-

ates, Flagstaff, Arizona, USA) to promote periodon-

tal reattachment and bone regeneration. For 10 days

after surgery, 400mg Clont (metronidazole, Infek-

topharm, Heppenheim, Germany) was prescribed

three times a day to prevent membrane infections, as

recommended by the ePTFE membrane manufac-

turer. For 14 days after surgery, the patient was

advised not to clean the teeth in the surgical area.

During the first week after surgery, a 0.1% chlorhex-

idine digluconate (CHX, Chlorhexamed

Fluid 0.1%,

GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare, Bhl, Ger-

many) solution was prescribed for mouth rinsing, and

for up to 6 weeks after surgery, a 1% CHX gel (Chlor-

hexamed

1% gel, GlaxoSmithKline Consumer

Healthcare) was prescribed to be applied locally. The

membranes were removed 6 weeks later in a second

surgery. To stabilise and preserve the maxillary ante-

rior teeth (13 to 23), a surgical treatment without the

regenerative procedure was performed; this involved

surgical scaling and root planing to eliminate the

biofilm and deposits on the roots in this sextant.

Phase III treatment

After completing the above procedures, the patient

received maintenance therapy 4 times a year. This

included non-surgical scaling and root planing of all

the remaining sites that had periodontal pockets

deeper than 3mm. Due to the recession of the gin-

giva at sites that formerly had deep pockets (Fig 1),

the patient developed hypersensitivities in teeth with

exposed root surfaces. These hypersensitivities per-

sisted over a period of about 1 year after the syste-

matic periodontal phase I and II treatments. In addi-

tion, the patient requested an aesthetic correction of

the maxillary anterior teeth due to the widely

exposed root surfaces. An artificial gingiva was cre-

ated (Fig 6a and b) to improve the aesthetic appear-

ance. The functional and aesthetic results of this min-

imal prosthetic treatment were very good. Due to the

tea drinking habits of the patient, the artificial gingiva

discoloured after about 1 year; thus, it was replaced

every year.

In 2005, the patient experienced increased bleed-

ing at localised sites. A DNA test (micro-Ident

, Hain

Diagnostika, Reutlingen, Germany) was performed

to identify the specific periodontal pathogens asso-

ciated with the bleeding periodontal sites. The results

showed high concentrations of Aggregatibacter

actinomycetemcomitans (10

5

), Porphyromonas gin-

givalis (10

6

), Tannerella forsythensis (10

6

), and Tre-

ponema denticola (10

5

). Retreatment began with an

anti-infective full-mouth disinfection therapy

12

com-

bined with a systemic antibiotic regime (previously

described by Van Winkelhoff et al)

13

. This procedure

stabilised the periodontal conditions within a few

weeks, and the bleeding stopped.

Treatment outcome

Figures 1 to 5 show the clinical and radiographic

findings at the beginning of the treatment in 1993

compared with the long-term results after a period

of 14 years. The periodontal treatment procedure

PERIO 2008;5(4):251258

255 Pelka/Petschelt Therapy of hopeless teeth

Fig 6a and b Clinical

frontal view with a gin-

giva mask, in situ. 6b

shows two gingiva

masks. A new gingiva

mask prior to insertion

(i) and a gingiva mask 1

year after insertion (ii).

The discolouration is

clearly visible.

b a

C

o

pyr

i

g

h

t

b

y

N

o

t

f o

r

Q

u

i

n

t

e

s

s

en

c

e

N

o

t

f

o

r

P

u

b

l

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

significantly reduced the vertical height of the gin-

giva (Fig 1). Comparing the clinical anterior views

over the years, it is remarkable that there were no

tooth movements. The proximal gap between teeth

11 and 12 was closed by the adhesive widening of

tooth 11. The course of the gingival margin changed

from 1993 to 1996, but after that, no further change

could be detected.

Furthermore, no further bone loss was observed

after treatment. Sites with localised intrabony defects

that underwent the surgical regenerative procedure

gained about 2 to 3mm of bone. The reappearance

of the cortical bone structure was a sign of stable

periodontal conditions (Figs 2 and 4). The teeth in

the maxillary anterior sextant that had sustained

horizontal bone loss of about 80 to 90% of the root

length showed some bone regeneration (1 to 2mm)

after treatment. The surrounding alveolar bone

showed all the signs of a stable periodontal condition

(Fig 2).

The maxillary anterior teeth required restabilisa-

tion over time, and broken proximal composite

splints were frequently repaired. From the aesthetic

point of view, the results were not optimal, due to the

large number of front teeth with widely exposed root

surfaces. The artificial gingiva was, therefore, a good

solution for improving the aesthetics of the anterior

teeth. The patient showed extremely good compli-

ance and excellent manual deftness in cleaning the

interproximal spaces (the approximal plaque and

bleeding indices decreased around 5 to 10%). This,

along with the periodical periodontal supportive

therapy, extended the success of the treatment for a

long period of time and prevented further bone or

tooth loss.

Discussion

This long-term case provides valuable support of the

notion that tooth preservation should always be a

treatment option, especially for patients that have

aggressive periodontitis. These patients are usually

under 40 years old, and commonly have complete

dentitions prior to the diagnosis of the disease. It is

associated with high bone loss and often results in

one or more hopeless teeth, with bone height losses

greater than 70% of the root length at the proximal

surface, and increased tooth mobility

11

. The extrac-

tion of hopeless teeth must be followed by an

implant or prosthetic therapy, with all the associated

problems.

This case is an excellent example of the success-

ful preservation of hopeless teeth and even slight

bone gain 14 years after therapy. Other studies have

shown that at an average of 4 to 8 years after ther-

apy, no bone loss was observed in the teeth and bone

adjacent to hopeless teeth

11,14

. Thus, the assump-

tion that further bone loss will occur at hopeless

tooth sites or at neighbouring sites is not always jus-

tified and should not constitute the sole reason for

the extraction of those teeth.

In this case, the extraction of the hopeless teeth

would have resulted in a small alveolar bone ridge

that was unsuitable for immediate implant insertion.

A stable implant insertion and good aesthetic clinical

results would have required extensive bone augmen-

tation or a surgical maxillary sinus augmentation

15,16

.

These implant procedures are often necessary for

prosthetic treatments with fixed crowns and FDPs.

There are many studies regarding implant treat-

ments under healthy periodontal conditions, but there

are only a limited number regarding patients with

advanced aggressive periodontitis

17

. Little is known

about disease progression and the potential impact on

adjacent teeth, on implants, or on the risk of develop-

ing peri-implantitis

18

. In patients with treated aggres-

sive periodontitis, implants have only been successful

under conditions where patients strictly maintained

healthy periodontal conditions

19-21

.

In this case study, an alternative treatment could

have been the extraction of the hopeless teeth fol-

lowed by an exclusively prosthetic treatment without

implants. Due to the high vertical bone loss in the

anterior maxillary region, this conventional prosthetic

treatment would have been aesthetically comparable

to the option we chose with no extraction. The pon-

tics would have been rather long, but the critical

deciding point was the high risk of endodontic com-

plications involved in the crown preparation of elon-

gated non-carious teeth. Moreover, it would not

have provided a satisfactory long-term treatment.

Thus, it was decided not to perform an exclusive

prosthetic treatment due to the doubtful aesthetic

outcome due to this solution, combined with the

additional endodontic risk.

PERIO 2008;5(4):251258

256 Pelka/Petschelt Therapy of hopeless teeth

C

o

pyr

i

g

h

t

b

y

N

o

t

f o

r

Q

u

i

n

t

e

s

s

en

c

e

N

o

t

f

o

r

P

u

b

l

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

Teeth were preserved that had a maximum bone

height of 20 to 30% of the root length. There was

some uncertainty at the beginning of the treatment

as to whether or not this solution would last and be

stable and acceptable to the patient. Our results

showed that the bone level was stable over 14 years

and, even in sites that did not receive the surgical

regenerative procedure, the bone height slightly

increased 1 or 2mm above the levels before treat-

ment.

The prescription of metronidazole for 10 days after

each surgical regenerative procedure was a common

treatment option in the mid 90s to prevent membrane

infections, after surgical regenerative procedures using

non-bioresorbable membranes. Nowadays the anti-

biotic treatment would precede the surgical treatment

and would be carried out during the phase I therapy

according the full-mouth disinfection concept. For

regeneration of intrabony defects, membranes as well

as enamel matrix proteins could be used. Due to the

high complication rate using non-bioresorbable mem-

branes, surgical regenerative procedures are usually

done with enamel matrix proteins. When using these

proteins an accompanying antibiotic treatment is not

necessary.

One unanswered question is how long will this

situation remain stable? Although certainty cannot

be achieved without data, in the authors experience,

the periodontal situation will remain stable and free

of inflammation with continuous oral hygiene and

periodical maintenance therapy. Any slackening of

oral hygiene will result in inflammation with bleed-

ing on probing; these signs of disease activity are

monitored at every maintenance session. A second

factor that might limit long-term tooth preservation

is the occurrence of caries at the root surfaces. Caries

often occur on proximal sites or in furcations, and

under these conditions, tooth preservation becomes

limited or impossible.

Tooth preservation of even heavily periodontally

affected teeth is a viable treatment decision for

patients with a low budget. Systematic periodontal

treatment followed by maintenance therapy is inex-

pensive compared with implant surgery and pros-

thetic rehabilitation. This case study showed that sys-

tematic non-surgical and surgical treatments can

preserve even hopeless teeth and stabilise or improve

bone levels over a period of 14 years.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the authors propose the following

guidelines for treating patients under 40 years with

advanced aggressive periodontitis and hopeless

teeth.

If dentition is complete, preservation of teeth

with advanced bone loss is possible.

If oral hygiene is acceptable, further disease pro-

gression in the affected teeth can be prevented

and formerly hopeless teeth can be preserved

over a long time period.

The bone levels on adjacent teeth and on hope-

less teeth can show small bone gains over time.

References

1. Tonetti MS, Mombelli A. Early-onset periodontitis. Ann Peri-

odontol 1999;4:39-53.

2. Gunsolley JC, Califano JV, Koertge TE, Burmeister JA, Cooper

LC, Schenkein HA. Longitudinal assessment of early onset

periodontitis. J Periodontol 1995;66:321-328.

3. Cichon P, Crawford L, Grimm WD. Early-onset periodontitis

associated with Downs syndrome. A clinical interventional

study. Ann Periodontol 1998;3:370-380.

4. Kamma JJ, Nakou M, Baehni PC. Clinical and microbiological

characteristics of smokers with early onset periodontitis. J

Periodontal Res 1999;34:25-33.

5. Mooney J, Hodge PJ, Kinane DF. Humoral immune response

in early-onset periodontitis: influence of smoking. J Periodon-

tal Res 2001;36:227-232.

6. Oh TJ, Eber R, Wang HL. Periodontal diseases in the child and

adolescent. J Clin Periodontol 2002;29:400-410.

7. Schenkein HA, Van Dyke TE. Early onset periodontitis: sys-

temic aspects of etiology and pathogenesis. Periodontol 2000

1994;6:7-25.

8. Sigusch B, Klinger G, Glockmann E, Simon HU. Early-onset

and adult periodontitis associated with abnormal cytokine

production by activated T lymphocytes. J Periodontol 1998;

69:1098-1104.

9. Vandesteen GE, Williams BL, Ebersole JL, Altman LC, Page

RC. Clinical, microbiological and immunological studies of a

family with a high prevalence of early-onset periodontitis. J

Periodontol 1984;55:159-169.

10. American Academy of Periodontology. Parameter on aggres-

sive periodontitis. J Periodontol 2000;71:867-869.

11. Machtei EE, Hirsch I. Retention of hopeless teeth: the effect

on the adjacent proximal bone following periodontal surgery.

J Periodontol 2007;78:2246-2252.

12. Quirynen M, Mongardini C, Pauwels M, Bollen CM, Van EJ,

van SD. One stage full- versus partial-mouth disinfection in

the treatment of chronic adult or generalized early-onset peri-

odontitis. II. Long-term impact on microbial load. J Periodon-

tol 1999;70:646-656.

13. van Winkelhoff AJ, Rodenburg JP, Goene RJ, Abbas F, Winkel

EG, de Graaff J. Metronidazole plus amoxycillin in the treat-

ment of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans associated

periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol 1989;16:128-131.

14. Wojcik MS, DeVore CH, Beck FM, Horton JE. Retained hope-

less teeth: lack of effect periodontally-treated teeth have on

PERIO 2008;5(4):251258

257 Pelka/Petschelt Therapy of hopeless teeth

C

o

pyr

i

g

h

t

b

y

N

o

t

f o

r

Q

u

i

n

t

e

s

s

en

c

e

N

o

t

f

o

r

P

u

b

l

i

c

a

t

i

o

n

the proximal periodontium of adjacent teeth 8-years later.

J Periodontol 1992;63:663-666.

15. Hrzeler MB, Kirsch A, Ackermann KL, Quinones CR. Recon-

struction of the severely resorbed maxilla with dental implants

in the augmented maxillary sinus: a 5-year clinical investiga-

tion. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants 1996;11:466-475.

16. Yang J, Lee HM, Vernino A. Ridge preservation of dentition

with severe periodontitis. Compend Contin Educ Dent

2000;21:579-583.

17. Mengel R, Flores-de-Jacoby L. Implants in patients treated for

generalized aggressive and chronic periodontitis: a 3-year

prospective longitudinal study. J Periodontol 2005;76:534-543.

18. Meffert RM. Periodontitis and periimplantitis: one and the

same? Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent 1993;5:79-80, 82.

19. Carlsson GE, Hedegard B, Koivumaa KK. Late results of treat-

ment with partial dentures. An investigation by questionnaire

and clinical examination 13 years after treatment. J Oral

Rehabil 1976;3:267-272.

20. Lang NP, Wilson TG, Corbet EF. Biological complications with

dental implants: their prevention, diagnosis and treatment.

Clin Oral Implants Res 2000;11(Suppl 1):146-155.

21. Nevins ML, Gartner-Sekler JL. Periodontal, implant, and pros-

thetic treatment for advanced periodontal disease. Compend

Contin Educ Dent 1997;18:469.

PERIO 2008;5(4):251258

258 Pelka/Petschelt Therapy of hopeless teeth

You might also like

- Margaret McWilliams-Fundamentals of Meal ManagementDocument361 pagesMargaret McWilliams-Fundamentals of Meal ManagementSaher Yasin89% (9)

- Letter of Intent (LOI) TemplateDocument1 pageLetter of Intent (LOI) Templatesmvhora100% (1)

- Cosmic Biology Science The Eye of RaDocument6 pagesCosmic Biology Science The Eye of RaBlackHerbals100% (2)

- Prezentare ReabilitareDocument20 pagesPrezentare ReabilitareCenean VladNo ratings yet

- Orthodontic Correction of Midline Diastema in Aggressive Periodontitis: A Clinical Case ReportDocument4 pagesOrthodontic Correction of Midline Diastema in Aggressive Periodontitis: A Clinical Case ReportIOSRjournalNo ratings yet

- An Integrated Treatment Approach: A Case Report For Dentinogenesis Imperfecta Type IIDocument4 pagesAn Integrated Treatment Approach: A Case Report For Dentinogenesis Imperfecta Type IIpritasyaNo ratings yet

- Perio PaperDocument9 pagesPerio Paperapi-391478637No ratings yet

- Viêm nha chu mạn toàn thểDocument5 pagesViêm nha chu mạn toàn thểtân hàNo ratings yet

- Management of Teeth With Trauma Induced Crown Fractures and Large Periapical Lesions Following Apical Surgery (Apicoectomy) With Retrograde FillingDocument5 pagesManagement of Teeth With Trauma Induced Crown Fractures and Large Periapical Lesions Following Apical Surgery (Apicoectomy) With Retrograde FillingUmarsyah AliNo ratings yet

- Interdisciplinary Orthodontics: A ReviewDocument7 pagesInterdisciplinary Orthodontics: A ReviewGauri KhadeNo ratings yet

- Peri ImplantitisDocument12 pagesPeri ImplantitisbobNo ratings yet

- Surgical Vs Non-Surgical Approach in PeriodonticsDocument13 pagesSurgical Vs Non-Surgical Approach in PeriodonticsBea DominguezNo ratings yet

- Combined Root Canal Therapies in Multirooted Teeth WithPulpal DiseaseDocument22 pagesCombined Root Canal Therapies in Multirooted Teeth WithPulpal DiseaseRen LiNo ratings yet

- MainDocument11 pagesMainDentist HereNo ratings yet

- Orthodontic Treatment of Periodontal Patients ChalDocument38 pagesOrthodontic Treatment of Periodontal Patients ChalJUAN FONSECANo ratings yet

- Oktawati 2020Document3 pagesOktawati 2020Mariatun ZahronasutionNo ratings yet

- Full Mouth Fixed Implant Rehabilitation in A Patient With Generalized Aggressive PeriodontitisDocument6 pagesFull Mouth Fixed Implant Rehabilitation in A Patient With Generalized Aggressive PeriodontitisFernando CursachNo ratings yet

- Asian Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial SurgeryDocument7 pagesAsian Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial SurgeryMichaelAndreasNo ratings yet

- 6.14 - EN Relação Entre Tratamento Ortodôntico e Saúde Gengival-Um Estudo Retrospectivo.Document8 pages6.14 - EN Relação Entre Tratamento Ortodôntico e Saúde Gengival-Um Estudo Retrospectivo.JOHNNo ratings yet

- Guo Et Al 2011: Full-Mouth Rehabilitation of A Patient With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Clinical ReportDocument5 pagesGuo Et Al 2011: Full-Mouth Rehabilitation of A Patient With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Clinical Reportmoji_puiNo ratings yet

- Apexogenesis After Initial Root CanalDocument8 pagesApexogenesis After Initial Root CanalZita AprilliaNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment Planning of Fixed ProsthodonticDocument15 pagesDiagnosis and Treatment Planning of Fixed ProsthodonticM.R PsychopathNo ratings yet

- Open Drainage or NotDocument6 pagesOpen Drainage or Notjesuscomingsoon2005_No ratings yet

- Periodontal Treatment in A Generalized Severe Chronic Periodontitis Patient: A Case Report With 7 Year Follow UpDocument5 pagesPeriodontal Treatment in A Generalized Severe Chronic Periodontitis Patient: A Case Report With 7 Year Follow UpFachriza AfriNo ratings yet

- Sopravvivenza Perioprotesi Di FeboDocument6 pagesSopravvivenza Perioprotesi Di FeboSadeer RiyadNo ratings yet

- The Management of Gingival Hyperplasia On Patient With Orthodontic TreatmentDocument7 pagesThe Management of Gingival Hyperplasia On Patient With Orthodontic TreatmentPuspandaru Nur Iman FadlilNo ratings yet

- Laporan Kasus 1 - Ayu Khoirun Nisa 22010220210013Document27 pagesLaporan Kasus 1 - Ayu Khoirun Nisa 22010220210013fadiahannisaNo ratings yet

- Lesi Endo-PerioDocument4 pagesLesi Endo-PerioFlorin AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Results of Peri-Implant Conditions in Periodontally Compromised Patients Following Lateral Bone AugmentationDocument10 pagesLong-Term Results of Peri-Implant Conditions in Periodontally Compromised Patients Following Lateral Bone AugmentationNosaci AndreiNo ratings yet

- A Case Report Using Regenerative Therapy For Generalized Aggressive PeriodontitisDocument9 pagesA Case Report Using Regenerative Therapy For Generalized Aggressive PeriodontitisripadiNo ratings yet

- Aesthetic Rehabilitation in Teeth With Wear From Bruxism and Acid ErosionDocument8 pagesAesthetic Rehabilitation in Teeth With Wear From Bruxism and Acid ErosionMarcos CarolNo ratings yet

- Histological Comparison of Pulpal Inflamation in Primary Teeth With Occlusal or Proximal CariesDocument8 pagesHistological Comparison of Pulpal Inflamation in Primary Teeth With Occlusal or Proximal CariesGilmer Solis SánchezNo ratings yet

- Endo Ortho ProsthoDocument346 pagesEndo Ortho ProsthoRohan Bhagat100% (1)

- D L, H R & L L: Periodontology 2000Document24 pagesD L, H R & L L: Periodontology 2000ph4nt0mgr100% (1)

- BY Janani.N Omfs PGDocument15 pagesBY Janani.N Omfs PGjanani narayananNo ratings yet

- Seminar 6 Preventive Prosthodontics in CD WordDocument29 pagesSeminar 6 Preventive Prosthodontics in CD Wordketaki kunteNo ratings yet

- Artigo BomDocument6 pagesArtigo BomCiro GassibeNo ratings yet

- He Mi Section For Treatment of AnDocument49 pagesHe Mi Section For Treatment of AnDr.O.R.GANESAMURTHINo ratings yet

- 3 Badr2016Document22 pages3 Badr2016Daniel Espinoza EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Clark Seminars in Orthodontics Perio Considerations Dec 7 09Document55 pagesClark Seminars in Orthodontics Perio Considerations Dec 7 09edi1988No ratings yet

- эндо имплантDocument6 pagesэндо имплантVitaliy PylypNo ratings yet

- Tendência 2021Document7 pagesTendência 2021ludovicoNo ratings yet

- Implantes Cortos y BruxismoDocument7 pagesImplantes Cortos y BruxismoManu AvilaNo ratings yet

- Generalized Aggressive Periodontitis CausesDocument7 pagesGeneralized Aggressive Periodontitis CausesAhmed DawodNo ratings yet

- Dental Trauma - An Overview of Its Influence On The Management of Orthodontic Treatment - Part 1.Document11 pagesDental Trauma - An Overview of Its Influence On The Management of Orthodontic Treatment - Part 1.Djoka DjordjevicNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of An Essential Oil Mouthrinse in Improving Oral Health in Orthodontic PatientsDocument5 pagesEffectiveness of An Essential Oil Mouthrinse in Improving Oral Health in Orthodontic PatientsHamza GaaloulNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Guey-Lin HouDocument8 pagesResearch Article: Guey-Lin HouLouis HutahaeanNo ratings yet

- Brighter Futures - Orthodontic Endodontic Considerations Part 2Document4 pagesBrighter Futures - Orthodontic Endodontic Considerations Part 2Valonia IreneNo ratings yet

- Three Different Surgical Techniques of Crown Lengthening: A Comparative StudyDocument10 pagesThree Different Surgical Techniques of Crown Lengthening: A Comparative StudyWiet SidhartaNo ratings yet

- DR Bhaumik Nanavati Proof ApprovedDocument6 pagesDR Bhaumik Nanavati Proof ApprovedFahmi FirmansyahNo ratings yet

- 1 Barsness2016Document24 pages1 Barsness2016Daniel Espinoza EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Orthodontic Treatment in Patients With ADocument8 pagesOrthodontic Treatment in Patients With Ahafizhuddin muhammadNo ratings yet

- Periodontally Compromised vs. Periodontally Healthy Patients and Dental Implants: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument19 pagesPeriodontally Compromised vs. Periodontally Healthy Patients and Dental Implants: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisLuis Fernando RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Melissa ArticuloDocument11 pagesMelissa ArticuloGLADYS VALENCIANo ratings yet

- New Treatment Option For An Incomplete Vertical Root Fracture Case StudyDocument4 pagesNew Treatment Option For An Incomplete Vertical Root Fracture Case StudyTarun KumarNo ratings yet

- Complete Healing of A Large Periapical Lesion Following Conservative Root Canal Treatment in Association With Photodynamic TherapyDocument9 pagesComplete Healing of A Large Periapical Lesion Following Conservative Root Canal Treatment in Association With Photodynamic TherapyAlina AlexandraNo ratings yet

- 243 674 1 PB PDFDocument2 pages243 674 1 PB PDFsurgaNo ratings yet

- Ortho - Perio CasesDocument31 pagesOrtho - Perio CasesChhavi SinghalNo ratings yet

- Tooth Splinter Lodged in The Lower Lip Subsequent To Trauma and Its Treatment Options: A Case Report.Document5 pagesTooth Splinter Lodged in The Lower Lip Subsequent To Trauma and Its Treatment Options: A Case Report.Dr.Vasundhara vermaNo ratings yet

- Vestibular Deepening To Improve Periodontal Pre-ProstheticDocument5 pagesVestibular Deepening To Improve Periodontal Pre-ProstheticRAKERNAS PDGI XINo ratings yet

- Full Mouth RehabDocument37 pagesFull Mouth RehabAravind Krishnan100% (6)

- Extrusion Splint Technique in Management of Dental Trauma: A Case ReportDocument5 pagesExtrusion Splint Technique in Management of Dental Trauma: A Case ReportdrvarunmalhotraNo ratings yet

- Treatment Planning Single Maxillary Anterior Implants for DentistsFrom EverandTreatment Planning Single Maxillary Anterior Implants for DentistsNo ratings yet

- PAG PDC MP ARLS SPC 001 Specification For Piping Material Class REV.a IFRDocument15 pagesPAG PDC MP ARLS SPC 001 Specification For Piping Material Class REV.a IFRChieAstutiaribNo ratings yet

- Safety Relief Valve Data SheetDocument30 pagesSafety Relief Valve Data SheetChieAstutiaribNo ratings yet

- Deliveriable List StatusDocument3 pagesDeliveriable List StatusChieAstutiaribNo ratings yet

- Lplpo Harian GudangDocument12 pagesLplpo Harian GudangChieAstutiaribNo ratings yet

- Penelitian IkgmDocument4 pagesPenelitian IkgmChieAstutiaribNo ratings yet

- An Audit of Impacted Mandibular Third Molar SurgeryDocument5 pagesAn Audit of Impacted Mandibular Third Molar SurgeryChieAstutiaribNo ratings yet

- Intrauterine Growth Restriction: Dr. Majed Alshammari, FRSCSDocument72 pagesIntrauterine Growth Restriction: Dr. Majed Alshammari, FRSCSapi-3703352No ratings yet

- Roberto Padlan (Resume)Document5 pagesRoberto Padlan (Resume)Merian PadlanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 103 PHCDocument47 pagesChapter 103 PHCYassir OunsaNo ratings yet

- Life Declaration - 30-03-2017Document1 pageLife Declaration - 30-03-2017Ananda Vijayasarathy0% (1)

- Acker Lawrence 2009 Social Work and Managed Care Measuring Competence Burnout and Role Stress of Workers ProvidingDocument15 pagesAcker Lawrence 2009 Social Work and Managed Care Measuring Competence Burnout and Role Stress of Workers ProvidingLina Marcela Rincón BarónNo ratings yet

- Role of Human Capital in Economic DevelopmentDocument9 pagesRole of Human Capital in Economic DevelopmentYeasir Malik100% (1)

- Medical Act of 1959Document11 pagesMedical Act of 1959Pogo Loco100% (1)

- Research Argumentative EssayDocument6 pagesResearch Argumentative EssayHoney LabajoNo ratings yet

- Steps of Research ProcessDocument4 pagesSteps of Research ProcessSudeep SantraNo ratings yet

- Case Pres 317 - GADDocument25 pagesCase Pres 317 - GADPAOLA LUZ CRUZNo ratings yet

- Psychiatric Nursing: Behavioral AnalysisDocument40 pagesPsychiatric Nursing: Behavioral AnalysisNichael John Tamorite RoblonNo ratings yet

- Chip Handbook of Help 2023 FinalDocument76 pagesChip Handbook of Help 2023 FinalLeTaia DuncanNo ratings yet

- Anticoagulation For Chronic Kidney DisiesesDocument9 pagesAnticoagulation For Chronic Kidney DisiesesorelglibNo ratings yet

- Flammable & Combustable LiquidsDocument3 pagesFlammable & Combustable LiquidssizweNo ratings yet

- Hazard Identification Risk Assessment and Determine Control (HIRADC)Document28 pagesHazard Identification Risk Assessment and Determine Control (HIRADC)Shida ShidotNo ratings yet

- BiaDocument7 pagesBiaDian WijayantiNo ratings yet

- Ayano 2016Document5 pagesAyano 2016Gemala AdillawatiNo ratings yet

- Rehabilitation: Presented By: Mohd Hatta Bin Hasenan 2009398407 Khairul Aiman Bin Ahmad Hafad 2009959475Document13 pagesRehabilitation: Presented By: Mohd Hatta Bin Hasenan 2009398407 Khairul Aiman Bin Ahmad Hafad 2009959475Hatta HasenanNo ratings yet

- Doterra Grapefruit Essential OilDocument1 pageDoterra Grapefruit Essential OilAlexandru Eduard RotaruNo ratings yet

- Source: Theory and Rationale of Industrial Hygiene Practice: Patty's Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology, P. 14Document17 pagesSource: Theory and Rationale of Industrial Hygiene Practice: Patty's Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology, P. 14angeh morilloNo ratings yet

- Theoretical Approaches To Multicultural Positive Psychological I 2019 PDFDocument549 pagesTheoretical Approaches To Multicultural Positive Psychological I 2019 PDFBonifar Jr BarluadoNo ratings yet

- Thank You For Your Purchase!Document2 pagesThank You For Your Purchase!Adrian MorganNo ratings yet

- Theatre Operational PolicyDocument26 pagesTheatre Operational PolicyEmma Sunday OdyenyNo ratings yet

- 8 Abdul MajidDocument5 pages8 Abdul MajidAnggreni YudhawatiNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Herbs For Cancer in Ayurveda - Cancer TreatmentDocument8 pagesTop 10 Herbs For Cancer in Ayurveda - Cancer TreatmentSN WijesinheNo ratings yet

- Food Security and Vision 2025Document38 pagesFood Security and Vision 2025madihaNo ratings yet

- Franklin Nguyen 11g2 Lesson 12 HealthDocument5 pagesFranklin Nguyen 11g2 Lesson 12 HealthLeanhtuan NguyenNo ratings yet