Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Heeled Shoes and Singing The Columbian National Anthem? - Yet You Understood It!)

Heeled Shoes and Singing The Columbian National Anthem? - Yet You Understood It!)

Uploaded by

sanshinde10Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Heeled Shoes and Singing The Columbian National Anthem? - Yet You Understood It!)

Heeled Shoes and Singing The Columbian National Anthem? - Yet You Understood It!)

Uploaded by

sanshinde10Copyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 1 - Grammatical Foundations: Words the speakers head to enable them to do this.

As you can imagine, this is not always easy and there is a lot of room for differences of opinion. Some of us might tell you that that is exactly what makes linguistics interesting. There are however some things we can assume from the outset about the linguistic system without even looking too closely at the details of language. First, it seems that speakers of a language are able to produce and understand a limitless number of expressions. Language simply is not a confined set of squeaks and grunts that have fixed meanings. It is an everyday occurrence that we produce and understand utterances that probably have never been produced before (when was the last time you heard someone say the bishop was wearing a flowing red dress with matching high heeled shoes and singing the Columbian national anthem? yet you understood it!). But if language exists in our heads, how is this possible? The human head is not big enough to contain this amount of knowledge. Even if we look at things like brain cells and synapse connections, etc., of which there is a very large number possible inside the head, there still is not the room for an infinite amount of linguistic knowledge. The answer must be that this is not how to characterise linguistic knowledge: we do not store all the possible linguistic expressions in our heads, but something else which enables us to produce and understand these expressions. As a brief example to show how this is possible, consider the set of numbers. This set is infinite, and yet I could write down any one of them and you would be able to tell that what I had written was a number. This is possible, not because you or I have all of the set of numbers in our heads, but because we know a small number of simple rules that tell us how to write numbers down. We know that numbers are formed by putting together instances of the ten digits 0,1,2,3, etc. These digits can be put together in almost any order (as long as numbers bigger than or equal to 1 do not begin with a 0) and in any quantities. Therefore, 4 is a number and so is 1234355, etc. But 0234 is not a number and neither is qewd. What these examples show is that it is possible to have knowledge of an infinite set of things without actually storing them in our heads. It seems likely that this is how language works. So, presumably, what we have in our heads is a (finite) set of rules which tell us how to recognise the infinite number of expressions that constitute the language that we speak. We might refer to this set of rules as a grammar, though there are some linguists who would like to separate the actual set of rules existing inside a speakers head from the linguists guess of what these rules are. To these linguists a grammar is a linguistic hypothesis (to use a more impressive term than guess) and what is inside the speakers head IS language, i.e. the object of study for linguistics. We can distinguish two notions of language from this perspective: the language which is internal to the mind, call it I-language, which consists of a finite system and is what linguists try to model with grammars; and the language which is external to the speaker, E-language, which is the infinite set of expressions defined by the I-language that linguists take data from when formulating their grammars. We can envisage this as the following:

You might also like

- Swedish English Frequency Dictionary - Essential Vocabulary - 2500 Most Used Words: SwedishFrom EverandSwedish English Frequency Dictionary - Essential Vocabulary - 2500 Most Used Words: SwedishRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- Italian English Frequency Dictionary - Essential Vocabulary - 2.500 Most Used Words & 421 Most Common VerbsFrom EverandItalian English Frequency Dictionary - Essential Vocabulary - 2.500 Most Used Words & 421 Most Common VerbsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (14)

- Portuguese English Frequency Dictionary - Essential Vocabulary - 2.500 Most Used Words: Portuguese, #1From EverandPortuguese English Frequency Dictionary - Essential Vocabulary - 2.500 Most Used Words: Portuguese, #1Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (3)

- Living Lingo (Introduction)Document24 pagesLiving Lingo (Introduction)OggieVoloderNo ratings yet

- Excerpt From: Louder Than Words: The New Science of How The Mind Makes MeaningDocument3 pagesExcerpt From: Louder Than Words: The New Science of How The Mind Makes MeaningL. J.No ratings yet

- Introduction To LinguisticsDocument29 pagesIntroduction To LinguisticsPawełNo ratings yet

- Grammatical Foundations: Words: 1 Language, Grammar and Linguistic TheoryDocument1 pageGrammatical Foundations: Words: 1 Language, Grammar and Linguistic Theorysanshinde10No ratings yet

- Psycholinguistics INTRODUCTIONDocument7 pagesPsycholinguistics INTRODUCTIONDRISS BAOUCHE100% (1)

- C. Exploration: Analysis and ReflectionDocument12 pagesC. Exploration: Analysis and ReflectionYasir ANNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document5 pagesChapter 1VeronicaNo ratings yet

- Part 1 - LiDocument12 pagesPart 1 - LiFarah Farhana Pocoyo100% (1)

- Jackendoff Patterns of The Mind - AnalysisDocument9 pagesJackendoff Patterns of The Mind - AnalysisDiego AntoliniNo ratings yet

- G Re 7 Dy 2 HSTGDocument28 pagesG Re 7 Dy 2 HSTGsanderlord1No ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Word, DictionaryDocument2 pagesChapter 2 Word, Dictionaryanggi100% (1)

- 2nd Stream PDFDocument4 pages2nd Stream PDFDaniela Jane Echipare TalanganNo ratings yet

- Scaffolding RDNG Comp For Title 1 ConfDocument35 pagesScaffolding RDNG Comp For Title 1 ConfmarleneNo ratings yet

- Layout Chapter 1+ pp1-17Document17 pagesLayout Chapter 1+ pp1-1701Nguyễn Phúc An9A2No ratings yet

- Why Study Linguistics?: Produced by The Subject Centre For Languages, Linguistics and Area StudiesDocument35 pagesWhy Study Linguistics?: Produced by The Subject Centre For Languages, Linguistics and Area StudiesCrisbel JuradoNo ratings yet

- Properties of LanguageDocument6 pagesProperties of LanguageFaisal JahangirNo ratings yet

- PsycholinguisticsDocument68 pagesPsycholinguisticsCarla Naural-citeb67% (3)

- Generative Grammar Chpter1Document21 pagesGenerative Grammar Chpter1نبيل العساليNo ratings yet

- LL NerdDocument5 pagesLL NerdSanthana Krishnan BNo ratings yet

- MAED English Language AquisitionDocument5 pagesMAED English Language Aquisitionkerrin galvezNo ratings yet

- TEXTO 4 - Studying SyntaxDocument11 pagesTEXTO 4 - Studying SyntaxNataly MoyanoNo ratings yet

- Relevant Linguistics, Ch. 1 Relevant Linguistics, Ch. 1Document12 pagesRelevant Linguistics, Ch. 1 Relevant Linguistics, Ch. 1Isaac MoralesvasNo ratings yet

- Cuadernillo Linguistica 2022Document34 pagesCuadernillo Linguistica 2022Damián OrtizNo ratings yet

- Thrasher 2002 Workshop Text MergedDocument33 pagesThrasher 2002 Workshop Text Mergedsubtitle kurdiNo ratings yet

- What Is Language?: Linguistic KnowledgeDocument6 pagesWhat Is Language?: Linguistic KnowledgeDendi Darmawan100% (1)

- Hayes Introductory Linguistics 2010Document451 pagesHayes Introductory Linguistics 2010hangadrottinNo ratings yet

- Lecture Notes LinguisticsDocument159 pagesLecture Notes LinguisticsjasorientNo ratings yet

- Language and The Brain: 1 Lesson 5Document6 pagesLanguage and The Brain: 1 Lesson 5Jenipher AbadNo ratings yet

- Episode 67 Transcript - Listening TimeDocument5 pagesEpisode 67 Transcript - Listening TimeKevin H.No ratings yet

- Introduction To Psycholinguistics (PPT) - 2Document10 pagesIntroduction To Psycholinguistics (PPT) - 2DR BaoucheNo ratings yet

- Language Development by Noam ChomskyDocument7 pagesLanguage Development by Noam ChomskyMohammad TeimooriNo ratings yet

- Introduction To PsycholinguisticsDocument59 pagesIntroduction To PsycholinguisticsRahmad ViantoNo ratings yet

- PrezentacjaDocument3 pagesPrezentacjaJakub BańduraNo ratings yet

- Brain & Language DevelopmentDocument46 pagesBrain & Language Developmentmbballera10No ratings yet

- 1st and 2ndDocument5 pages1st and 2ndmosab77No ratings yet

- El103 - Module 1Document6 pagesEl103 - Module 1Mark Kaven LazaroNo ratings yet

- Part 1Document14 pagesPart 1feraNo ratings yet

- Theories of The Early Stages of LanguageDocument7 pagesTheories of The Early Stages of LanguageErmalyn Saludares MunarNo ratings yet

- 311 Course Notes WK 1 Intro PDFDocument10 pages311 Course Notes WK 1 Intro PDFChloe SaundersNo ratings yet

- What Is LanguageDocument4 pagesWhat Is LanguageUmais QureshiNo ratings yet

- Haegeman Main IdeasDocument2 pagesHaegeman Main IdeasAgustina PuertoNo ratings yet

- The Brain and LanguageDocument4 pagesThe Brain and LanguageDenada Aulia RahmadinaNo ratings yet

- Deatras Theory of Language Acquisition - BAEL 1-ADocument3 pagesDeatras Theory of Language Acquisition - BAEL 1-ANeo ArtajoNo ratings yet

- How Words Are LearnedDocument3 pagesHow Words Are LearnedYohanes M Restu Dian RNo ratings yet

- ACFrOgBSaAdJ6Arc90mIpXQqBQTg2-QfEmWVK38 Vvt9eDxeHeXP463VA Civg827DPVhjuyBb2zRdEO9zDl md5P68lu-ozAOzzQhdr3dyPpdmecYZLBXbqluP8sZbGNGkfrEu6E1HyZ0UzTgQNDocument6 pagesACFrOgBSaAdJ6Arc90mIpXQqBQTg2-QfEmWVK38 Vvt9eDxeHeXP463VA Civg827DPVhjuyBb2zRdEO9zDl md5P68lu-ozAOzzQhdr3dyPpdmecYZLBXbqluP8sZbGNGkfrEu6E1HyZ0UzTgQNCarolina Cortondo MondragónNo ratings yet

- Homework 3Document1 pageHomework 3salomon quirozNo ratings yet

- What Is The Lexical Approach? Michael Lewis PAGS 7 A 14Document8 pagesWhat Is The Lexical Approach? Michael Lewis PAGS 7 A 14Leonete FernandesNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Building Techniques: A Guide To Learn The Words That Only Natives UseDocument8 pagesVocabulary Building Techniques: A Guide To Learn The Words That Only Natives UseMax AhumadaNo ratings yet

- The Vocabulary We Have Does More Than Communicate Our Knowledge It Shapes What We Can Know Evaluate This Claim With Reference To Different Areas of KnowledgeDocument8 pagesThe Vocabulary We Have Does More Than Communicate Our Knowledge It Shapes What We Can Know Evaluate This Claim With Reference To Different Areas of KnowledgeWendy Teng Ieng LeongNo ratings yet

- Fundamentos de La EnseñanzaDocument20 pagesFundamentos de La EnseñanzaMoiraAcuñaNo ratings yet

- Linguistic Universals: Ian Roberts, Chapter 10Document11 pagesLinguistic Universals: Ian Roberts, Chapter 10Michael SchiffmannNo ratings yet

- Rss - II - Midterm - Exam KopyasıDocument3 pagesRss - II - Midterm - Exam KopyasıhilalsuexeNo ratings yet

- 1AX LT Learning Words Grant GoodallDocument6 pages1AX LT Learning Words Grant GoodallRachNo ratings yet

- Who Says Learning Spanish Can't Be Fun: The 3 Day Guide to Speaking Fluent SpanishFrom EverandWho Says Learning Spanish Can't Be Fun: The 3 Day Guide to Speaking Fluent SpanishNo ratings yet

- Swedish English Frequency Dictionary II - Intermediate Vocabulary - 5001 - 7500 Most Used Words & Verbs: Swedish, #3From EverandSwedish English Frequency Dictionary II - Intermediate Vocabulary - 5001 - 7500 Most Used Words & Verbs: Swedish, #3No ratings yet

- The Child and the World: How the Child Acquires Language; How Language Mirrors the WorldFrom EverandThe Child and the World: How the Child Acquires Language; How Language Mirrors the WorldNo ratings yet

- Hi My Name Is Santosh I Will Be Training You One Fengshui BasicDocument1 pageHi My Name Is Santosh I Will Be Training You One Fengshui Basicsanshinde10No ratings yet

- Fengshui Santosh Page1Document1 pageFengshui Santosh Page1sanshinde10No ratings yet

- Hi My Name Is Santosh I Will Be Training You One Fengshui BasicDocument1 pageHi My Name Is Santosh I Will Be Training You One Fengshui Basicsanshinde10No ratings yet

- Cbt13 Schooldays.1Document1 pageCbt13 Schooldays.1sanshinde10No ratings yet

- Chapter 1. What's The Story?Document5 pagesChapter 1. What's The Story?sanshinde10No ratings yet

- Basic Electronics 9Document1 pageBasic Electronics 9sanshinde10No ratings yet

- Basic Electronics 10Document1 pageBasic Electronics 10sanshinde10No ratings yet

- Basic Electronics 45Document1 pageBasic Electronics 45sanshinde10No ratings yet

- Basic Electronics 6Document1 pageBasic Electronics 6sanshinde10No ratings yet

- Enno 3Document1 pageEnno 3sanshinde10No ratings yet

- Semi-Custom: - Lower Layers Are Fully or Partially BuiltDocument1 pageSemi-Custom: - Lower Layers Are Fully or Partially Builtsanshinde10No ratings yet

- General-Purpose Processors: - Programmable Device Used in A Variety of Applications - FeaturesDocument1 pageGeneral-Purpose Processors: - Programmable Device Used in A Variety of Applications - Featuressanshinde10No ratings yet

- Full-custom/VLSI: - All Layers Are Optimized For An Embedded System's Particular Digital ImplementationDocument1 pageFull-custom/VLSI: - All Layers Are Optimized For An Embedded System's Particular Digital Implementationsanshinde10No ratings yet

- PLD (Programmable Logic Device) : - All Layers Already ExistDocument1 pagePLD (Programmable Logic Device) : - All Layers Already Existsanshinde10No ratings yet

- IC Technology: - Three Types of IC TechnologiesDocument1 pageIC Technology: - Three Types of IC Technologiessanshinde10No ratings yet

- HindiDocument12 pagesHindiAditya JainNo ratings yet

- Attendance:: Sekolah Kebangsaan Nanga Temalat English Language Panel Meeting Minutes 1/2019Document4 pagesAttendance:: Sekolah Kebangsaan Nanga Temalat English Language Panel Meeting Minutes 1/2019zainina zulkifliNo ratings yet

- A Universal Approach To MetaphorsDocument9 pagesA Universal Approach To MetaphorsudonitaNo ratings yet

- A2 UNIT 1 Extra Grammar Practice ExtensionDocument1 pageA2 UNIT 1 Extra Grammar Practice ExtensionCarolinaNo ratings yet

- Social Science Disciplines: Subject: Disciplines and Ideas in The Social Sciences - Module 2Document9 pagesSocial Science Disciplines: Subject: Disciplines and Ideas in The Social Sciences - Module 2Paby Kate AngelesNo ratings yet

- Compendium in Teaching Grammar Its Techniques Approaches and StrategiesDocument106 pagesCompendium in Teaching Grammar Its Techniques Approaches and Strategiesmelacl10100% (1)

- Introduction To AmbahanDocument4 pagesIntroduction To AmbahanCharles BusilNo ratings yet

- Bahasa Inggris Teknik SipilDocument2 pagesBahasa Inggris Teknik SipilM. Dimas BaihaqiNo ratings yet

- Learning Modern Greek On The Web: The 'Filoglossia' SoftwareDocument7 pagesLearning Modern Greek On The Web: The 'Filoglossia' SoftwareIoana ConstandinouNo ratings yet

- Equative, Comparative & Superlative AdjectivesDocument20 pagesEquative, Comparative & Superlative AdjectivesLeidy Cristina Hurtado100% (1)

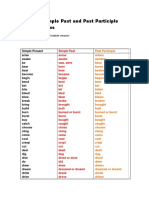

- Irregular Simple Past and Past Participle Verb FormsDocument4 pagesIrregular Simple Past and Past Participle Verb FormsAlvaro Owen0% (1)

- English 7 Q3 DLL JVVDocument33 pagesEnglish 7 Q3 DLL JVVjohn rex100% (1)

- Shinasha Morphology, A Sketch of (Rottland)Document25 pagesShinasha Morphology, A Sketch of (Rottland)Hamid LeNo ratings yet

- StartersDocument4 pagesStartersAlejandra ZuletaNo ratings yet

- Japanese Phonetics by Dōgen BibliographyDocument3 pagesJapanese Phonetics by Dōgen BibliographyCsssraNo ratings yet

- Grammar SectionDocument16 pagesGrammar SectionShakeelAhmedNo ratings yet

- English Plus планирование (все уровни)Document44 pagesEnglish Plus планирование (все уровни)Венера А.No ratings yet

- Exercise Answers - Units 1 2Document9 pagesExercise Answers - Units 1 2Mert Can BalkNo ratings yet

- Error Correction PDFDocument41 pagesError Correction PDForlandohs11No ratings yet

- Translation Translation-InterpretationDocument4 pagesTranslation Translation-InterpretationAnh NgocNo ratings yet

- Types of NounsDocument4 pagesTypes of NounsLady Lou LepasanaNo ratings yet

- PhoneticsDocument134 pagesPhoneticsArabella Mae DuqueNo ratings yet

- All ModsDocument231 pagesAll ModsKritNo ratings yet

- (OS 052) Gordon, de Moor (Eds.) - The Old Testament in Its World - Papers Read at The Winter Meeting January 2003 PDFDocument304 pages(OS 052) Gordon, de Moor (Eds.) - The Old Testament in Its World - Papers Read at The Winter Meeting January 2003 PDFOudtestamentischeStudien100% (2)

- The English We SpeakDocument2 pagesThe English We Speakcaeronmustai100% (1)

- Past Simple Review: Watched Films With Her New FriendsDocument3 pagesPast Simple Review: Watched Films With Her New FriendsÓscar Alejandro Bernal ObandoNo ratings yet

- Twitter Sentiment Analysis: The Good The Bad and The OMG!: Efthymios Kouloumpis Theresa Wilson Johanna MooreDocument4 pagesTwitter Sentiment Analysis: The Good The Bad and The OMG!: Efthymios Kouloumpis Theresa Wilson Johanna MooreChivukula BharadwajNo ratings yet

- Kinds of Sentences and Their Punctuation: Coordinating Conjunction Conjunctive Adverb SemicolonDocument41 pagesKinds of Sentences and Their Punctuation: Coordinating Conjunction Conjunctive Adverb SemicolonMarwaNo ratings yet

- Simple Present: I He We She You It They YouDocument1 pageSimple Present: I He We She You It They YouSivoldy CarlosNo ratings yet

- PREP-R. Protocolo Rápido de Evaluación Pragmática Revisado: January 2015Document4 pagesPREP-R. Protocolo Rápido de Evaluación Pragmática Revisado: January 2015Laura R. Asalde Rojas100% (1)