Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ingold, Tim. The Conical Lodge at The Centre of The Earth.

Ingold, Tim. The Conical Lodge at The Centre of The Earth.

Uploaded by

Eguia MarianaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ingold, Tim. The Conical Lodge at The Centre of The Earth.

Ingold, Tim. The Conical Lodge at The Centre of The Earth.

Uploaded by

Eguia MarianaCopyright:

Available Formats

THE CONICAL LODGE AT THE CENTRE OF THE EARTH-SKY WORLD

Tim Ingold University of Aberdeen

Department of Anthropology School of Social Science University of Aberdeen Aberdeen AB24 3QY Scotland, U tim!ingold"abdn!ac!#$

December 2%&%, revised A#g#st 2%&&

I 'n the gro#nds of (roms) *#se#m, a conical tent or lodge had been erected of a $ind traditionally #sed among indigeno#s, forest+d,elling peoples right aro#nd the circ#mpolar -orth ./ig#re &0! (he frame ,as made of long, sto#t ,ooden poles that converged at the ape1, b#t splayed o#t at gro#nd level aro#nd the perimeter of a circle! (his ,as covered ,ith laborio#sly prepared reindeer s$ins, caref#lly se,n together! (ho#gh e1tending all the ,ay to the base of the frame, they reached not 2#ite to the ape1 b#t to a level 3#st short of it, leaving the ape1 itself #ncovered! 4ntering thro#gh the door+flap, ' fo#nd myself in a remar$ably capacio#s, interior space, at the centre of ,hich ,as a place for the fire! ' $nelt on the gro#nd! 't ,as still daytime and the light ,as streaming in thro#gh the ape1, ,hich remained open to the s$y! 5oo$ing #p, it made me blin$ ./ig#re 20! At the same time, thro#gh my $nees, ' felt the clammy depth of the earth ,hich gave me s#pport! 'n a moment of revelation, ' #nderstood ,hat it meant to inhabit a ,orld of earth and s$y! 't ,as to be at once bathed in light and rapt in feeling! B#t it also da,ned on me ho, closely the idea of landscape to ,hich ' ,as acc#stomed from my o,n #pbringing is lin$ed to a partic#lar architect#re6 to the habitation of rooms ,ith hard floors belo,, ceilings above, and ,indo,s set in vertical ,alls! 'magine yo#rself as the resident of a modern s#b#rban apartment, ,ith large pict#re ,indo,s that afford a commanding, panoramic vie, of the s#rro#nding co#ntryside! 7hen yo# loo$ o#t from the ,indo,s yo# see the land stretching o#t into the distance, ,here it seems to meet the s$y along the line of the far hori8on! 'nside the lodge, ho,ever, there ,ere no hori8ons to be seen! 4arth and s$y, far from being divided at the hori8on, seemed rather to be #nified at the very centre of my emplaced being!

4n,rapped ,ithin the lodge ' nevertheless felt open to a ,orld! B#t this ,orld ,as not a landscape b#t ,hat ' shall henceforth call the earth-sky! /#rther reflection led me to thin$ that ,hat is at iss#e here is not 3#st a partic#lar architect#re b#t the very idea of architect#re itself! /or more than five cent#ries, it has been both the claim and the conceit of the architect#ral profession that every b#ilding is a mon#ment to the geni#s of its creator, standing as the end#ring realisation of an original design concept! 'n the mid+fifteenth cent#ry, in his treatise On the Art of Building in Ten Books, 5eon Battista Alberti had painted an #nashamedly self+aggrandising portrait of the architect as a man of 9learned intellect and imagination:, ,ho is able 9to pro3ect ,hole forms in mind ,itho#t any reco#rse to the material: .Alberti &;<<6 =0! As one of the fo#nding fig#res of the 4#ropean >enaissance, Alberti can be seen in retrospect to stand at a pivotal 3#nct#re in the process that #ltimately led to the professionalisation of architect#re as a discipline e1cl#sively devoted to design as opposed to constr#ction! ?is treatise both loo$s bac$ to the time of his predecessors, the master b#ilders and 3o#rneymen of the medieval era, and for,ard to a time ,hen the architect ,o#ld prescribe only the formal o#tlines of the b#ilding, leaving its act#al constr#ction to masons, carpenters and other practitioners of the b#ilding trades! Yet in this idea of ma$ing or b#ilding as the pro3ection of pre+conceived form onto inert matter, Alberti dre, his inspiration from the more distant past of classical anti2#ity @ from the philosophical ,ritings of Aristotle! 'n the ma$ing of any artefact, Aristotle had reasoned, ideal form .morphe0 is #nified ,ith material s#bstance .hyle0, s#ch that the artefact is finished ,hen the once shapeless material has ta$en on the form intended for it! 5i$e,ise for Alberti, any b#ilding 9consists of lineaments and matter, the one the prod#ct of tho#ght, the other of -at#reA the one re2#iring the

po,er of reason, the other dependent on preparation and selection: .&;<<6 B0! 7hat Alberti calls 9lineaments: .lineamenta0 are the abstract lines of 4#clidean geometry, comprising the elements of formal design as conceived by the intellect! B#t neither lineaments nor matter, Alberti ,as 2#ic$ to add, ,o#ld on their o,n s#ffice to ma$e a b#ilding! (o fashion the material according to lineaments, in the ,or$ of constr#ction .structura0, called for the s$illed and capable hands of ,or$men! -ot only ,as the idea of architect#re entirely recast thro#gh its harnessing to the Aristotelian, so+called hylomorphic model of ma$ing! So too ,as the idea of landscape! (here is indeed an intrinsic connection bet,een the t,o ideas! (ho#gh art historians are inclined to associate the landscape ideal ,ith a certain style of pictorial representation, originally perfected by D#tch painters in the seventeenth cent#ry .Alpers &;<30, the ,ord itself is of early medieval origin, and refers literally to the shaping of the land, from Cld 4nglish sceppan or skyppan, meaning 9to shape: .Cl,ig 2%%<a0! *edieval land shapers, ho,ever, ,ere not artists or architects b#t farmers and ,oodsmen, ,hose p#rpose ,as not to lend ideal form to the material ,orld, or to render it in appearance rather than s#bstance, b#t to ,rest a living from the earth! 5i$e their co#nterparts in the b#ilding trades @ the masons and carpenters of medieval times @ their ,or$ ,as done close+#p, in an immediate, m#sc#lar and visceral engagement ,ith ,ood, stone and soil, the very opposite of the distanced, contemplative and panoramic optic that the ,ord 9landscape: con3#res #p in many minds today! /or it is not in agrarian or b#ilding practice that the roots of the modern landscape aesthetic are to be fo#nd, b#t in architect#re! Serving as both stage and scenery, the landscape is commonly ta$en to f#rnish not only the solid fo#ndations on ,hich the architect#ral mon#ment is erected b#t also the scenic bac$drop against

,hich it is displayed or 9set off: to best advantage! (ogether, the mon#ment and its landscape are #nderstood to comprise a totality that is complete and f#lly formed! ?ere, land is to scape as material s#bstance is to abstract form, and the land is shaped by their #nification! As historian Simon Schama ,rites, introd#cing his magn#m op#s on Landscape and Memory, the scenery 9is b#ilt #p as m#ch from strata of memory as from layers of roc$ Dit is o#r shaping perception that ma$es the difference bet,een ra, matter and landscape: .Schama &;;B6 =, &%0! 'f the bedroc$ of the physical ,orld provides the matter, then the h#man mind contrib#tes the form! 5and+scape, in short, e2#als matter+form! 7ith these reflections on the meanings of architect#re and landscape in mind, let me ret#rn to the conical lodge! 'n ,hat follo,s ' arg#e that ,e mis#nderstand the lodge by imagining it as an instance of architect#re6 that is, as a str#ct#re b#ilt to the prior specifications of a formal design, and set #pon the stage and amidst the scenery of a landscape! (hose ,ho hold s#ch a vie, @ and they incl#de a s#bstantial ma3ority in the fields of ethnology, c#lt#ral anthropology and material c#lt#re st#dies @ do recognise, of co#rse, that as an e1ample of ,hat is called 9vernac#lar: architect#re, the lodge manifests a design that is attrib#table to the geni#s of c#lt#ral tradition rather than individ#al creation! (he b#ilders of s#ch traditional str#ct#res, according to architect#ral theorist Ehristopher Ale1ander, do not $no,ingly implement designs of their o,n ma$ing b#t rather s#bmit to the reprod#ction of forms sanctified by ,eight of tradition! (heir b#ilding is, in this sense, 9#nselfconscio#s: .Ale1ander &;F46 3F0! -evertheless, the f#ndamental ass#mptions of the hylomorphic model remain! (hese are that ,hile the ra, materials of the lodge are s#pplied by nat#re, the form is added by c#lt#re, carried #n$no,ingly in the minds of the people and passed from generation to generation thro#gh force of c#stom and habit! 't is s#pposed that in

b#ilding the lodge, this ideal form is pro3ected #pon the s#bstrate of the material ,orld! (he alternative vie,, ,hich ' shall no, attempt to establish, is to comprehend the process of b#ilding not as a pro3ection of form onto matter b#t as a binding together of materials in movement! (h#s the lodge, far from being b#ilt #p #pon rigid and impervio#s fo#ndations, is stitched into the very fabric of the earth! 'nstead of thin$ing of the lodge, then, as a material artefact set in a landscape, it ,o#ld be better #nderstood as a ne1#s of materials in a ,orld of earth and s$y! (o establish this vie,, ' ,ill proceed in fo#r steps! 'n the first, ' e1amine the difference bet,een t,o ,ays of thin$ing abo#t b#ilding6 as the assembly of elementary solids and as the ,eaving and splicing of fibro#s material .'ngold 2%%%6 F4+BA 2%&&6 2&&0! 'n the second ' consider the essential m#t#ality of earth and s$y, and ,hat it means to say of the lodge that it is both of the earth and of the s$y! 'n the third step ' lin$ the idea of the earth+s$y, in contrast to landscape, to that of smooth space, and sho, ho, this lin$age is manifested in the materials of the lodge! /inally, ' e1plain the conical form of the lodge as an #pended spiral @ the envelope of a process of gro,th and regeneration!

II 7e are contin#ally being told, these days, that the ,orld ,e inhabit is b#ilt from bloc$s6 not 3#st the ,orld that ,e o#rselves have made @ of artefacts or the b#ilt environment @ b#t the ,orlds of nat#re, the mind, the #niverse and everything! Biologists spea$ of the b#ilding bloc$s of life, psychologists of the b#ilding bloc$s of tho#ght, physicists of the b#ilding bloc$s of the #niverse itself! So pervasive has this metaphor become that ,e are inclined to forget ho, recent it is! ' had not even realised this myself #ntil a year ago, ,hen ' chanced to read a little boo$, entitled The

most beautiful house in the world, by the architect#ral historian 7itold >ybc8yns$i! 't ,as not #ntil the middle of the nineteenth cent#ry, >ybc8yns$i tells #s, that the metaphor of 9b#ilding bloc$s: came into common #se, along ,ith a domestic architect#re @ of prospero#s homes e2#ipped ,ith dedicated n#rseries @ in ,hich b#ilding ,ith bloc$s co#ld literally become child:s play .>ybc8yns$i &;<;6 2;+3F0! Before that time, most play ,as o#t of doors, and even ,hen it too$ place indoors, floors ,ere too #neven, and too b#sy and cl#ttered, for any constr#ction to stand #p! /rom the &<B%s on,ards, ho,ever, the architect#ral profession actively promoted the development and mar$eting of sets of b#ilding bloc$s for children! 'nc#lcated from o#r earliest years, the ass#mption that the ,orld is b#ilt from bloc$s has since become part of the stoc$ in trade of modern tho#ght! /or the most part, it is invo$ed #ncritically, and ,itho#t a moment:s hesitation or reflection! 't is precisely this ass#mption that ' ,ant to 2#estion! ' shall do so by considering ,hat ,o#ld happen if ,e ,ere to thin$ of the b#ilding not as a constr#ction p#t together from solid bloc$s, b#t as a thing ,oven from pliant materials! 'n more technical terms this is to dra, a distinction bet,een stereotomics and tectonics! Stereotomics @ derived from the classical Gree$ stereo .solid0 and tomia .to c#t0 @ is the art of c#tting solids into elements that fit sn#gly together ,hen assembled into a str#ct#re li$e a ,all or a va#lt! (hese elements are, of co#rse, the b#ilding bloc$s to ,hich ,e are so acc#stomed! (ectonics, by contrast, is the art of assembling a frame from linear components, held together by 3oints or bindings rather than simply by the gravitational force of heavy,eight elements bearing do,n on those beneath and #ltimately on fo#ndations! Cne might thin$, for e1ample, of the frame of a boat that has still to be covered ,ith plan$s or s$ins, or the beams of a roof that has still to be thatched, slated or tiled! (he term tectonic comes from the Gree$ tekton,

originally referring to the ,or$ of the carpenter b#t s#bse2#ently e1tended to b#ilding or ma$ing in a more general sense! 't goes bac$ to the Sans$rit taksan, ,hich signified the craft of carpentry and specifically the #se of the a1e .tasha0! C#r 2#estion, then, is abo#t the balance @ or the relative priority @ of stereotomics and tectonics in the b#ilding of things! (his ,as a 2#estion that m#ch preocc#pied the historian of art and architect#re, Gottfried Semper! 7riting in the middle of the nineteenth cent#ry, 3#st as the stereotomic idea of b#ilding bloc$s ,as on the rise, Semper arg#ed in 3#st the opposite direction, namely that the threading, t,isting and $notting of linear fibres ,ere among the most ancient of h#man arts, from ,hich all else ,as derived, incl#ding both b#ilding and te1tiles! 9The beginning of building:, Semper declared, 9coincides with the beginning of textiles: .&;<;6 2B4, original emphasis0! (h#s the first ,alls ,ere plaited from stic$s and branches6 they ,ere fences and pens! /rom there it ,as a small step to the plaiting of basts, and thence to the techni2#e of ,eaving! (his, in t#rn, gave rise to pattern, and the ,eaving of patterns led to the emergence of the carpet! 7e tend to thin$ of ,alls as made of s#ch solid materials as bric$ or stone, and of ,all+b#ilders as masons or bric$layers! B#t follo,ing his chain of derivations, Semper concl#ded, 2#ite to the contrary, that the first 9,all+fitters: .Wandbereiter0 ,ere ,eavers of mats and carpets, noting in his s#pport that the German ,ord for ,all, Wand, shares the same root as the ,ord for dress or clothing, ewand .&;<;6

&%3+40! ?e also fo#nd etymological s#pport for his idea of the evol#tionary priority of the te1tilic arts in the affinity of the ,ords for the 3oint .!aht0 and the $not ."noten0, both ,ords being connected, in modern German, to the concept #erbindung .binding0! (h#s the carpenter, 3oining beams, and the ,eaver, bas$et+ma$er or carpet+ma$er,

<

binding and $notting threads or fibres, are engaged in the activities of the same general $ind ./rampton &;;B6 <F0! (he primordial d,elling, according to Semper, comprised fo#r f#ndamental elements! (hese are the earth,or$, the hearth, the frame,or$ and the enclosing membrane! (o each of these he assigned a partic#lar craft6 masonry for the earth,or$A ceramics for the hearthA carpentry for the frame,or$, and te1tiles for the membrane! (he $ey iss#e for him, ho,ever, ,as the relation bet,een the stereotomic base of the b#ilding, the earth,or$, and its tectonic frame @ and th#s bet,een masonry and carpentry! Admittedly, the earth,or$ co#ld rise #p into the fabric of the b#ilding itself, to form solid ,alls or fortifications of roc$ and stone! B#t Semper ,as caref#l to disting#ish bet,een the massiveness of the solid ,all, indicated by the ,ord Mauer, and the light, screen+li$e enclos#re signified by Wand! 'n relation to the latter:s primary f#nction of spatial enclos#re, Semper tho#ght, the former played a p#rely a#1iliary role, to provide protection or s#pport! (he essence of b#ilding, then, lay in the 3oining or $notting of linear elements of the frame, and the ,eaving of the material that covered it! 4ven ,ith the addition of stone ,alls and fortifications, b#ilding never lost its character as a te1tilic art! Semper:s essay on The $our %lements of Architecture ,as p#blished in &<F%! 't ,as not ,ell received! 5eading fig#res in the histories of art and architect#re lined #p to ridic#le it! 'ndeed the idea that b#ilding co#ld be a practice of ,eaving a$in to bas$etry seemed as strange to Semper:s contemporaries as it does to most of #s today! 't ta$es a bold intellect to 2#estion it! Cne s#ch ,as the eccentric philosopher of design, HilIm /l#sser .&;;;0! 7riting in the final decades of the t,entieth cent#ry, /l#sser reminds #s that for any str#ct#re that ,o#ld afford some meas#re of protection from the elements, s#ch as a tent, the first condition is not that it sho#ld ,ithstand the

force of gravity b#t that it sho#ld not be s,ept a,ay by the ,ind! (his leads him to compare the ,all of the tent ,ith the sail of a ship, or even the ,ing of a glider, the p#rpose of ,hich is not so m#ch to resist or brea$ the ,ind as to capt#re it into its folds, or to deflect or channel it, in a ,ay that serves the interests of h#man d,elling ./l#sser &;;;6 BF0! 7hat if ,e ,ere to follo, /l#sser and commence o#r #nderstanding of ,alls by thin$ing abo#t, and ,ith, the ,ind6 by flying $ites rather than b#ilding ,ith bloc$sJ >ather li$e Semper before him, /l#sser disting#ishes t,o $inds of ,all .corresponding to Wand and Mauer0, the screen ,all, generally of ,oven fabric, and the solid ,all, he,n from roc$ or b#ilt #p from heavy components! 7itho#t going into the 2#estion of relative antecedence, this for /l#sser is the difference bet,een the tent and the ho#se .&;;;6 BF+=0! (he ho#se is a geostatic assemblage of ,hich the elements are held firm by the sheer ,eight of bloc$s stac$ed atop one another! (he force of gravity allo,s the ho#se to stand, b#t e2#ally can bring it t#mbling do,n! 7ithin the cave+li$e enclos#re formed by the fo#r solid ,alls of the ho#se, /l#sser arg#es .&;;;6 B=0, things are possessed @ 9property is defined by ,alls:! (he tent, by contrast, is an aerodynamic str#ct#re that ,o#ld li$ely lift off, ,ere it not pegged, fastened or anchored to the gro#nd! 'ts fabric screens are ,ind ,alls! As a calming of the ,ind, a loc#s of rest in a t#rb#lent medi#m, the tent is li$e a nest in a tree6 a place ,here people, and the e1periences they bring ,ith them, come together, inter,eave and disperse in a ,ay that precisely parallels the treatment of fibres in fabricating the material from ,hich the tent:s screen ,alls are made! 'ndeed the very ,ord 9screen: s#ggests, to /l#sser, 9a piece of cloth that is open to e1periences .open to the ,ind, open to the spirit0 and that stores this e1perience: .&;;;6 B=0!

&%

As ho#se is to tent, then, and as the containment of life:s possessions o&er and against the ,orld is to the ,eaving together of life+paths in the ,orld, so is the clos#re of the solid roc$ ,all to the openness of the ,indblo,n screen ,all! 9(he screen ,all blo,ing in the ,ind:, /l#sser ,rites, 9assembles e1perience, processes it and disseminates it, and it is to be than$ed for the fact that the tent is a creative nest: ./l#sser &;;;6 B=0! Cf co#rse, li$e all s,eeping generalisations, this is far too cr#de, and any attempt to classify b#ilt forms in these terms ,o#ld immediately collapse #nder the ,eight of e1ceptions! (here are tents that incorporate roc$ ,alls, and ho#ses ,hose ,alls are screens! Cne has only to thin$, for e1ample, of the screen ,alls of the Kapanese ho#se! Laper+thin and semi+transl#cent, these ,alls defy any opposition bet,een inside and o#tside, and cast the life of inhabitants as a comple1 interplay of light and shado,! (he traditional Kapanese ho#se, as the architect#ral historian enneth /rampton has observed, belonged to a ,orld that ,as ,oven thro#gho#t, from the $notted grasses and rice stra, ropes of domestic shrines to tatami floor+mats and bamboo ,alls ./rampton &;;B6 &4+&F0! 'ndeed in its commitment to the tectonic, Kapanese b#ilding c#lt#re stands in star$ contrast to that of the ,estern mon#mental tradition ,ith its emphasis on stereotomic mass! (he general contrast bet,een the geostatics of the roc$ ,all and the aerodynamics of the ,ind ,all remains, ho,ever! 'ndependently of /l#sser, b#t dra,ing directly on the earlier ,or$ of Semper, /rampton ta$es #s bac$ to the fo#ndational distinction bet,een stereotomics and tectonics, and to the 2#estion of the balance bet,een them! (raditions of vernac#lar b#ilding aro#nd the ,orld reveal ,ide variations in this balance, depending on climate, c#stom and available material, from b#ildings @ s#ch as the Kapanese ho#se @ in ,hich the earth,or$ is red#ced to point fo#ndations ,hile ,alls as ,ell as roofs are ,oven, to traditional #rban d,ellings in

&&

-orth Africa ,here stone or m#d bric$ ,alls arch over to become roof va#lts of the same material, and in ,hich br#sh,or$ or bas$et,or$ serves only as reinforcement ./rampton &;;B6 F+=0! 'n the former case the stereotomic component, and in the latter case the tectonic component, is red#ced to a minim#m! 'n some instances, materials are transposed from the one mode of constr#ction to the other, s#ch as ,here stone is c#t to resemble the form of a timber frame .as in the classical Gree$ temple0, or ,here bric$s are not so m#ch heaped #pon one another as bonded into co#rse,or$ that has all the appearance of a ,eave! /rampton:s interest, ho,ever, lies in the 9cosmic associations evo$ed by these dialogically opposed modes of constr#ctionA that is to say the affinity of the frame for the immateriality of s$y and the propensity of mass form not only to gravitate to,ard the earth b#t also to dissolve in its s#bstance: .ibid!6 =0! 'n these associations, the b#ilding is revealed as a marriage not of form and matter b#t of earth and s$y, and as the cons#mmation of their #nion! (o thin$ of the b#ilding as s#ch is to sit#ate it in an earth+s$y ,orld!

III 't is in these terms, then, that ' propose to consider the conical lodge @ not as an artefact in the landscape b#t as a partic#lar synthesis of earth and s$y that allo,s h#man life to ta$e root and gro,, dra,ing s#stenance from the earth even as it breathes the air! 'n order to #nderstand the nat#re of this synthesis, let #s start from the gro#nd! ' have already noted ho, the idea of 9b#ilding bloc$s: pres#pposes a gro#nd that is level and rigid6 a fo#ndation #pon ,hich the ob3ects of o#r interest, or that afford everyday life, are mo#nted! 'n his manifesto for an ecological psychology, Kames Gibson compares the s#rface of the earth to the floor of a room! 5i$e the floor, he arg#es, the gro#nd is 9the #nderlying s#rface of s#pport: on ,hich all else rests

&2

.Gibson &;=;6 &%, 330! Yet a bare gro#nd, devoid of feat#res, ,o#ld be no more habitable than an #nf#rnished room! (o be rendered habitable, a room m#st be f#rnished ,ith the miscellany of ob3ects that ma$e possible the everyday activities carried on in it! Similarly, the gro#nd can harbo#r life only beca#se it, too, is f#rnished ,ith ob3ects of one $ind and another! 9(he furniture of the earth:, Gibson insists, 9li$e the f#rnishings of a room, is ,hat ma$es it livable: .&;=;6 =<0! K#st li$e the room, the earth is cl#ttered ,ith all manner of ob3ects ,hich afford the diverse activities of its inn#merable inhabitants! Among them ,o#ld be s#ch ob3ects as trees, stones D and b#ildings! -o, Gibson ,as among the first to challenge the once dominant vie, that people see the ,orld in pict#res, pro3ected onto the bac$ of the retina as if on a screen! As ' shall sho, belo,, there is a direct lin$ bet,een this notion of pro3ection and the idea of landscape in its modern sense! Arg#ing against this, Gibson placed perceivers at the centre of a ,orld that is all around them rather than arrayed in front of their eyes! ?e imagined this ,orld as comprising t,o hemispheres, of the s$y above and the earth belo,! At the interface bet,een the #pper and lo,er hemispheres, and stretching o#t to the great circle of the hori8on, lies the gro#nd on ,hich perceivers stand! Both littered on the gro#nd, and s#spended in the s$y, are the ob3ects of o#r perception! (h#s the inhabited environment incl#des not only earth and s$y, nor only the #niverse of ob3ects, b#t both together! 'n Gibson:s ,ords, it consists of 9the earth and the s$y ,ith ob3ects on the earth and in the s$y, of mo#ntains and clo#ds, fires and s#nsets, pebbles and stars: .&;=;6 FF0! (o ret#rn to the conical lodge, then, ,e co#ld pose the follo,ing 2#estion6 is the lodge an ob3ect on the earthJ 's it part of the f#rnit#reJ Cr is it rather, recalling o#r earlier disc#ssion of the aerodynamic properties of the tent, an ob3ect in the s$yJ 's it perhaps both, or neitherJ

&3

(he ans,er ' ,ish to propose is that the lodge is not an ob3ect at all b#t a thing! (he ob3ect e1ists as an entity in a ,orld of materials that have already precipitated o#t and solidified in fi1ed and final forms! 't stands before #s as a fait accompli, presenting only its congealed, o#ter s#rfaces to o#r inspection! (he thing, by contrast, is ever+emergent as a certain gathering or inter,eaving of materials in movement, in a ,orld contin#ally coming into being, al,ays on the threshold of the act#al! 7hereas the ob3ect, as /l#sser notes, 9gets in the ,ay: and bloc$s o#r passage ./l#sser &;;;6 B<0, the thing dra,s #s in along the very paths of its formation! 4ach, if yo# ,ill, is a 9going on: @ or better, a place ,here several goings on become ent,ined! As the philosopher *artin ?eidegger p#t it, albeit rather enigmatically, the thing presents itself 9in its thinging from o#t of the ,orlding ,orld: .?eidegger &;=&6 &<&0! (he e1ample that ?eidegger #sed to ill#strate his arg#ment ,as a simple 3#g! (he 3#g:s thinginess, he arg#ed, lies neither in its physical s#bstance nor in its formal appearance b#t in its capacity to gather, to hold and to give forth .&;=&6 &FF+=40! (here is of co#rse a precedent for this vie, of the thing as a gathering in the ancient meaning of the ,ord as a place ,here people ,o#ld gather to resolve their affairs! As the historical geographer enneth Cl,ig .2%%<b0 observes, in a brilliant acco#nt of the political geography of early medieval K#tland, the thing+place gathers the lives of people ,ho d,ell in the land, holds their collective memories and gives forth in the r#lings and resol#tions of #n,ritten la,! K#tland is dotted ,ith s#ch places! (o attend a thing, then, is not to be loc$ed o#t b#t to be invited into the gathering! 'f ,e thin$ of every participant as follo,ing a partic#lar ,ay of life, threading a line thro#gh the ,orld, then perhaps ,e co#ld define the thing, as ' have s#ggested else,here, as a 9parliament of lines: .'ngold 2%%=6 B0! (h#s conceived, the thing has the character not of an e1ternally bo#nded entity, set over and against the

&4

,orld, b#t of a $not ,hose constit#ent life+lines, far from being contained ,ithin it, contin#ally trail beyond, only to mingle ,ith other lines in other $nots! (he conical lodge, ' s#ggest is s#ch a thing ./ig#re 20! As s#ch, to ret#rn to o#r earlier 2#estion, the lodge is neither on the earth nor in the s$y! /or far from being confined to their respective domains by the hard s#rface of the gro#nd, in the constit#tion and dissol#tion of things earth and s$y contin#ally infiltrate one another! 7herever life is going on, indeed, the interfacial separation of earth and s$y gives ,ay to m#t#al permeability and binding! (he painter La#l lee bea#tif#lly evo$ed this binding in the image of a seed that has fallen to the gro#nd! 9(he relation to earth and atmosphere:, he ,rites, 9begets the capacity to gro, D (he seed stri$es root, initially the line is directed earth,ards, tho#gh not to d,ell there, only to dra, energy thence for reaching #p into the air: . lee &;=36 2;0! (he gro,ing plant is not mo#nted upon the gro#nd s#rface b#t rooted in it! /or that very reason it is sim#ltaneo#sly earthly and celestial! 't is so, as lee pointed o#t, since the commingling of s$y and earth is itself a condition for life and gro,th! 't is beca#se the plant is of .and not on0 the earth that it is also of the s$y! (he same applies to the conical lodge! 't, too, is at once of earth and s$y6 a place ,here earth and s$y are bro#ght together in the gro,th and e1perience of its inhabitants! 4vidently, then, the gro#nd of the lodge is no mere platform! 't is rather an enveloping matri1 that both anchors and no#rishes the lives of its inhabitants, 3#st as the gro#nd beyond its circ#mference n#rt#res the vegetation that gro,s there and the animal life that feeds on it! (h#s, the gro#nd o#tside the lodge does not resemble the gro#nd inside beca#se it is similarly f#rnished ,ith ob3ects! >ather, it is the gro#nd inside the lodge that resembles the gro#nd o#tside, since it provides shelter and no#rishment li$e the s#rro#nding earth! 't is in this gro#nd and not on it, as

&B

?eidegger p#t it @ in this earth, this 8one of gro,th and transformation @ that 9man bases his d,elling: .?eidegger &;=&6 420! 'n an admittedly florid passage, ?eidegger describes the earth as 9the serving bearer, blossoming and fr#iting, spreading o#t in roc$ and ,ater, rising #p into plant and animal: .ibid!6 &4;0! Yet this earth, ?eidegger insisted, is #nthin$able ,itho#t also thin$ing of the s$y, and vice versa! 4arth and s$y are not, then, separate hemispheres ,hich, p#t together, add #p to a #nity! >ather, each binds the other into its o,n becoming! (he earth binds the s$y in the tiss#es of the plants and animals it s#stains and no#rishesA the s$y s,eeps the earth in its c#rrents of ,ind and ,eather! And at the centre of this ,orld of earth and s$y lies the conical lodge!

IV 4ven if this arg#ment is accepted, ho,ever, ,e have still to acco#nt for the specific ,ay in ,hich earth and s$y are bro#ght together in the conical lodge! ?o,, for e1ample, does the lodge compare in this regard ,ith the traditional d,ellings of people ,ho lived by farming and forestry rather than by pastoral herdingJ Cne ,ay to thin$ abo#t this difference might be in terms of a distinction, introd#ced by philosopher Gilles Dele#8e and psychoanalyst /Ili1 G#attari, bet,een smooth and striated space! (his distinction ta$es #s bac$ to ,hat /l#sser called the screen ,all of the tent, and more partic#larly, to the material of ,hich it is made! >ecall that for /l#sser, the tent+,all is a ,oven fabric that gathers, holds and disseminates the lives of those ,ho d,ell ,ithin! As s#ch, it epitomises the very 9thinginess: of the lodge, in ?eidegger:s terms! 't is 9open to e1periences:, /l#sser says .&;;;6 B=0, and dra,s people in! B#t does it reallyJ Semper, after all, had ass#med to the contrary that the f#nction of the ,oven ,all ,as, first and foremost, to enclose .Semper &;<;6 2B4+B0!

&F

As the ,all of the fence or pen, ,oven from stic$s and branches, enclosed crops or herds, so that of the traditional ho#se, ,hose ,oven ,alls might have been plastered ,ith ,attle and da#b, enclosed its people! 7riting more than a cent#ry later, in &;<%, Dele#8e and G#attari appear at first glance to conc#r! /abric, they say, encloses, b#t the ,all of the nomadic tent is nevertheless open to e1perience in a ,ay that the ho#se ,all is not, precisely beca#se the e1emplary material of the tent, in their vie,, is not fabric at all, b#t felt! 7hereas the ,eaving of fabric entails the intert,ining of separate threads, ,ith felt there is 9no separation of threads, no intert,ining, only an entanglement of fibres:! 'n this regard, they contend, felt is the very opposite of fabric! 't is an 9anti+fabric: .Dele#8e and G#attari 2%%46 B2B0! (hey proceed to #se this opposition to e1emplify their distinction bet,een the striated and the smooth! (he former is the r#led and reg#lated space of an agrarian regime, stra$ed ,ith rigs and f#rro,s, as is cloth ,ith intersecting parallel threads of ,arp and ,eft! 't ,as in this sense that the land ,as shaped by farmers and ,oodsmen, in times gone by, thereby fashioning the landscape in the original, medieval meaning of the term! (he latter, by contrast, is the open space of nomadic herdsmen6 a heterogeneo#s mIlange of contin#o#s variation, e1tending ,itho#t limit and in all directions! As felt is made #p of entangled fibres, so the gro#nd of smooth space is comprised of the entangled tra3ectories of people and animals as they ,end their ,ays, follo,ing no predetermined direction b#t responding at every moment to locally prevailing conditions and the possibilities they afford to carry on! (here is ho,ever a catch in the arg#ment, ,hich even Dele#8e and G#attari themselves are forced to ac$no,ledge! 7hile felt is the predominant tent material of herding comm#nities thro#gho#t 'nner Asia, it is by no means common to pastoral peoples every,here! 'n many parts of the ,orld, tents are covered ,ith prepared

&=

animal hides, as indeed ,as the case in the lodge from ,hich ' began, clothed as it ,as ,ith a patch,or$ of reindeer s$ins! Dele#8e and G#attari are 2#ic$ to assimilate the patch,or$ @ 9an amorpho#s collection of 3#1taposed pieces that can be 3oined together in an infinite n#mber of ,ays: @ to their idea of smooth space .2%%46 B2F0! 't is li$e felt in having no consistent direction, or lines of striation! (he #se of fabric as tent covering, ho,ever, presents more of a problem! (he nomadic pastoralists of -orth Africa, for e1ample, $no, nothing of felting, nor do they cover their tents ,ith animal hides! >ather, they #se ,ool to ,eave their tent+cloth! ?o, can ,e ta$e ,oven fabric to be a hallmar$ of agrarian life, ,hen it is fo#nd e2#ally among pastoral nomadsJ (o get aro#nd the problem, Dele#8e and G#attari displace their initial distinction bet,een felt or patch,or$ and fabric onto one bet,een t,o $inds, or conceptions, of fabric, corresponding respectively to the striated and the smooth! Cn the one hand, they arg#e, among sedentary farmers @ inhabitants of the striated @ fabric enfolds the body and the o#tside ,orld ,ithin the confines of the immobile ho#se! ?ere, its f#nction is to enclose! (he fabric of nomads, on the other hand, 9inde1es clothing and the ho#se itself to the space of the o#tside, to the open, smooth space in ,hich the body moves: .2%%46 B2B0! K#st ho, one might disting#ish a fabric of the first $ind from one of the second is hard to say, and ,ith no means of doing so, the arg#ment does s#ffer from a certain circ#larity! -evertheless, ,ith this 2#alification, the respective claims of /l#sser and of Dele#8e and G#attari, apparently in contradiction, can be readily reconciled! 7e have merely to ac$no,ledge that /l#sser:s 9screen ,all: @ open to e1perience, spirit and ,ind @ is a ,oven fabric of the second $ind! And the implication is that as the setting of fabric shifts from tent to

&<

ho#se, so the open screen becomes a closed solid ,all or, more probably, a ,all+ covering or tapestry that hangs from it! 41actly the same happens ,ith the carpet, another invention of tent+d,ellers, as /l#sser goes on to sho,! (he carpet, he ,rites, is 9to the c#lt#re of the tent ,hat architect#re is to the c#lt#re of the ho#se: ./l#sser &;;;6 ;B0! 'nitially, ,hen carpets entered the ho#se, they ,ent #p on the ,alls! >ecall that even Semper referred to carpets as ,all+hangings and to carpet ,eavers as among the first ,all+fitters .Semper &;<;6 &%3+40! -o,adays, ho,ever, it is not on the ,alls that yo# ,o#ld e1pect to find a carpet! /or modern #rban d,ellers, the proper place for a carpet is the floor! As ,e have already seen, the pop#lar idea of b#ilding bloc$s calls for a floor that is perfectly level and rigid! /or the occ#pant of a ho#se or apartment in a modern metropolitan city, this is all a floor sho#ld be! 't is b#t a base, #pon ,hich can be mo#nted all the app#rtenances of everyday life! Strip all these things a,ay and the floor is left barren and lifeless! 't cries o#t to be covered! 7e are even inclined to e1tend this idea metaphorically to the gro#nd o#tside, ,hich ,e say is 9carpeted: ,ith vegetation! 7ith this idea of the gro#nd as a solid floor, covered ,ith a carpet and cl#ttered ,ith ob3ects as the interior room of the ho#se is cl#ttered ,ith f#rnit#re, the agrarian landscape of medieval times gives ,ay to the stage and scenery of the landscape in its modern incarnation6 as a space not of gathering b#t of pro3ection! Dele#8e and G#attari .2%%46 B43+40 disting#ish bet,een the haptic space of close+#p, hands+on engagement, for e1ample of the ,eaver ,ith her threads, the plo#ghman ,ith the soil, or the carpenter or mason ,ith ,ood or stone, and the optical space of distance and detachment, ,herein the forms of the architect#ral imagination, conceived off+site, are pro3ected onto material s#bstance! (hey are right to point o#t that this distinction cross+c#ts that bet,een eye and hand6 th#s one can see close #p

&;

.as in ,eaving0 and to#ch at a distance .s#ch as on a $eyboard0! (hey are ,rong, ho,ever, to e2#ate the opposition bet,een the haptic and the optical ,ith that bet,een the smooth and the striated! 't ,o#ld be closer to the mar$ to recognise that the optical and the haptic correspond to t,o ,ays of striating space! (his, indeed, is ,hat disting#ishes the modern sense of the landscape from its medieval prec#rsor .'ngold 2%&&6 &340! (he landscapes of modernity are striated, b#t not by the ,arp of the loom, the f#rro,s of the plo#gh or the mar$s and c#ts of masons and carpenters, ,hether etched in stone or follo,ing the grain of timber! >ather, they are striated by the abstract lineamenta, and by the ratios and proportions, of pro3ective geometry! (hese striations, then, are of an entirely different order! (o amplify the difference, ,e can ret#rn to /l#sser:s idea of the screen ,all! 7ith this idea, /l#sser is primarily thin$ing of the ,oven fabric of the tent covering! /or many contemporary readers, ho,ever, the ,ord 9screen: is more li$ely to bring to mind the opa2#e screens of pro3ection @ s#ch as in the cinema or conference room @ #pon ,hich are cast images of one $ind and another! E#rio#sly, /l#sser .&;;;6 B=0 believes that they, too, assemble and store e1perience, in 3#st the same ,ay as the fabric ,alls of the tent! (his, ho,ever, is precisely ,hat they do not do! 'n the cinema, the movements of life are pro3ected onto the screen, not dra,n into its fabric! (he screen itself remains blan$ly impervio#s to the images that play #pon its s#rface! 5ight, so#nd and feeling, the f#ndamental c#rrents of sensory e1perience for the tent+d,eller, are red#ced in the ,orld of cinematic representation to vectors of pro3ection in the conversion of ob3ects to images! 'ndeed the difference bet,een the screen as a ,oven fabric and as a s#rface of pro3ection precisely parallels the contrast in ,ays of thin$ing abo#t b#ilding, bet,een

2%

the gathering together of materials in movement and the pro3ection of ideal form onto material s#bstance, that ' have so#ght to establish! 9(he #navoidably earthbo#nd nat#re of b#ilding:, ,rites /rampton .&;;B6 20, 9is as tectonic and tactile in character as it is scenographic and vis#al:! Cnly in the former sense co#ld it be said, ,ith /l#sser, that the screen ,all is 9open to e1perience:! (his leaves #s ,ith one problem, ho,ever, that has still to be resolved! ?o,, e1actly, does the perception of nomadic pastoralists, the archetypal deni8ens of smooth space, differ from that of sedentary farmers in their hands+on activities of shaping the landJ ?o, do the gatherings and ,eavings, and the sensory engagements, of smooth space differ from those of the striatedJ Cnly ,hen ,e have ans,ered this 2#estion can ,e finally p#t o#r finger on the specificity of the ,ay in ,hich earth and s$y come together in the conical lodge!

V All life is lived #nder the s#n, and in this, the farmer is no e1ception! Leople ,ho ,rest a living from the land have also to contend ,ith the vagaries of ,ind and ,eather, ,hatever their mode of s#bsistence! 9't is evident that the peasant:, ,rite Dele#8e and G#attari, 9participates f#lly in the space of the ,ind, the space of tactile and sonoro#s 2#alities: .2%%46 B3%+&0! (his is not an optical space @ a space of pro3ection @ ,herein the ,orld is revealed to the beholder in a manner a$in to images on a screen, nor is it a haptic space of close+#p engagement ,ith the materials of life! 't is rather atmospheric, a space of light, so#nd and feeling that inf#ses the body, sat#rates a,areness, and both constit#tes and #nder,rites the capacities of inhabitants to see, to hear and to to#ch! (o inhabit the atmosphere is to see ,ith the light of the s#n, to hear ,ith the so#nds of the elements and to to#ch ,ith the breath of the ,ind .'ngold 2%&&6 &340! B#t ,hile nomad and peasant may live #nder the same s$y, and

2&

imbibe the same atmosphere, their respective relations to the earth are f#ndamentally different! /or in the peasant:s labo#r of shaping the land, the earth presents itself as a field not of forces to be harnessed b#t of resistances to be overcome! ?ere, earth and s$y meet not in #nison b#t in discord @ a discord played o#t in the constr#ction of the d,elling, as ,e have already seen, in the opposed principles of stereotomics and tectonics! 7hereas in the tent of the nomad, earth and s$y meet at the hearth, in the ho#se of the peasant they are divided bet,een the stereotomic mass of the ,alls and fo#ndations, ,hich gravitate to,ards the earth, and the tectonic frame and covering of the roof, ,hich mingles ,ith the s$y! 'n the division bet,een roof and ,alls, the peasant d,elling is divided against itself! (he ,orld of the peasant, ,e might say, is not so m#ch an earth-sky as an earth'sky! (o highlight the contrast, let me introd#ce another comparison, bet,een the farmer:s life on land and the mariner:s at sea! (he ocean is s#rely smooth space par excellence! (he mariner ensconced in his vessel, feeling the ,aves as they lap the h#ll and catching the ,ind in his sails, all the ,hile scanning the s$y for the movements of birds by day and of the stars and other celestial bodies by night, is a point of rest in a ,orld in ,hich all aro#nd is in movement .Glad,in&;F46 &=&+20! 'n striving to rein in the forces of the elements he is the precise opposite of the farmer ,ho bends m#scle and sine, to co#nteract the friction of an immobile and often #nyielding earth, dragging himself and his e2#ipment over the hard gro#nd and inscribing trac$s and path,ays in the process! (o describe the mariner:s s#rro#ndings from the farmer:s perspective, as a seascape .Eooney 2%%30, ,o#ld be to confer on ,aves and tro#ghs, or on becalmed or t#rb#lent ,aters, a permanence and solidity that they lac$ in reality! Setting sail, the mariner does not simply relin2#ish one set of s#rfaces, of the land, for another, of the sea! >ather he enters a ,orld in ,hich s#rfaces ta$e second place to the circ#lations of the

22

media in ,hich they are formed! ?ere the gro#nded fi1ities of landscape give ,ay to the aerial fl#1es of ,ind and ,eather above, and the a2#atic fl#1es of tide and c#rrent belo,! (hese fl#1es, and not the s#rface of the sea, absorb the mariner:s effort and attention! (he ,orld he inhabits is not, then, a seascape b#t an ocean-sky( Eo#ld the same not be said of the nomadic pastoralistJ *#ch as mariners ride the ,aves, nomads ride the past#res, carried along on the ,inds,ept e1panses of sand, steppe and sno,, and responding in their movements, at every moment, to real and imaginary forces, both celestial and s#bterranean .'ngold 2%&&6 &330! At home in the lodge, the nomad feels the earth ,ith his body as his ga8e mingles ,ith the s$y! As a centre of stillness and a calming of the ,inds, the conical lodge is indeed comparable to a vessel at sea, and not 3#st in the fact that the covering of both boat and lodge is stretched over a tectonic frame! 7e have reports of *icronesian mariners lying on the bottoms of their canoes ,hen travelling far o#t of sight of land, sensing the s,ell ,ith their bodies ,hile ga8ing directly heaven,ards .*ac$ 2%%=6 &33+40! 'f for the mariner in his boat, the ,orld is a blend of s$y and ocean, then for the nomadic pastoralist in the lodge, it is li$e,ise a blend of s$y and earth! (his is to thin$ of the land as smooth rather than of the sea as striated! (here are s#rfaces in the earth+s$y ,orld, of co#rse! B#t they are s#rfaces of a different $ind! (he landscape, carved and striated, has t#rned against the s$y! 't is, as Dele#8e and G#attari say .2%%46 B3%0, closed off and apportioned! B#t in the smooth space of the earth+s$y, the s#rfaces of the land @ li$e those of the sea @ open #p to the s$y and embrace it! 'n their ever+ changing colo#rs, and patterns of ill#mination and shade, they reflect its lightA they resonate in their so#nds to the passing ,inds, and in their feel #nderfoot or #nder+hoof they respond to the dryness or h#midity of the air, depending on heat or rainfall! 'n

23

smooth space, to contin#e ,ith Dele#8e and G#attari, 9there is no line separating earth and s$y: .2%%46 42&0! Cne co#ld not e1ist ,itho#t the other! 'n his Tristes Tropi)ues, Ela#de 5Ivi+Stra#ss lin$ed the birth of architect#re to the invention of ,riting, and both to the creation of cities and empires ,ith their attendant str#ct#res of po,er and e1ploitation .5Ivi+Stra#ss&;BB6 2;;0! Both ,riting and architect#re strive for hierarchy, mon#mentality and permanence! (heir forms are stereotomic, assembled from bloc$s and made to last! 'n the tectonic ,orld of the earth+s$y, ho,ever, nothing lasts6 there are no indelible records, end#ring mon#ments or rigid hierarchies! /rom an architect#ral point of vie,, the b#ilt forms of the earth+ s$y ,orld appear ephemeral @ as ephemeral, even, as spo$en ,ords! 't ,o#ld seem, indeed, that the mon#ment is to the lodge, and the landscape to the earth+s$y, precisely as ,riting is to speech! K#st as the ,ords of oral narrative dissolve in the very act of their prod#ction, so the binding of materials in smooth space is al,ays accompanied by their #nbinding! And yet the lodge, as ,e have seen, is a thing, and the thing @ to recall ?eidegger:s ,ords @ carries on 9in its thinging, from o#t of the ,orlding ,orld: .&;=&6 &<&0! (o inhabit the lodge is to 3oin ,ith its thinging, in the material flo,s and circ#lations of vital force of ,hich its form is the ever+emergent o#tcome! 7hereas the mon#ment ,as b#ilt, once and for all, the lodge is al,ays b#ilding and reb#ilding! (h#s for the inhabitant of the ,orlding ,orld, it is the architect#ral mon#ment that seems ephemeral, b#ried in the sands of time ,hile life goes on! As ,riting event#ally fades, so also @ in time @ the mon#ment, tho#gh designed to last in perpet#ity, crac$s and cr#mbles! (he lodge, ho,ever, persists, in a constant process of rene,al, 3#st as do the narratives that inhabitants tell in it! ' have so#ght to #nderstand the conical lodge as a loc#s of gro,th and regeneration in an earth+s$y ,orld, ,here materials ,elling #p from #nder the gro#nd

24

mi1 and mingle ,ith air and moist#re from the atmosphere in the ongoing prod#ction of life! As a gathering place of forces and materials, the lodge is not closed over! 't does not t#rn its bac$ on #s! 't is open6 a confl#ence of persons and materials, dra,n together in the movements of its formation! At the generative heart of the lodge is the fire+place, the hearth! And ,here life binds, in the gro,th of living things, fire #nbinds, in their comb#stion .'ngold 2%&&6 &220! 'n the smo$e of the fire, materials no#rished by the earth, and bo#nd together in life, are released once more to the s$y, ,hence they ,ill f#el f#rther gro,th! (o concl#de, ' ,ant to s#ggest that it is in relation to this perpet#al cycle of binding and #nbinding that ,e sho#ld #nderstand the conical form of the lodge! 'nstead of thin$ing of this form in terms of p#re geometry, as a Llatonic solid set #pon a plane, ,e sho#ld perhaps regard it as the envelope of an #p,ard spiral @ that is, as an #pended vorte1 ,ith the hearth as its eye! (he spiral is a movement that goes aro#nd and #p, rather than a s#rface that divides inside from o#tside! 't th#s signifies gro,th and regeneration rather than enclos#re! 'n short, as a vorte1 in the c#rrents of earth and air, ,here the smo$e from the hearth rises to meet the s$y, the conical lodge brings to a foc#s the generative fl#1es of the ,orlding ,orld!

2B

Reference Alberti, 5! B! &;<<! On the art of building in ten books, trans! K! >y$,ert, -! 5each and >! (avernor! Eambridge, *ass6 *'( Lress! Ale1ander, E! &;F4! !otes on the synthesis of form! Eambridge, *ass!6 ?arvard University Lress! Alpers, S! &;<3! The art of describing* +utch art in the se&enteenth century! 5ondon6 Leng#in! Eooney, G! 2%%3! 'ntrod#ction6 seeing the land from the sea! World Archaeology 3B.306 323+32<! Dele#8e, G! and /! G#attari 2%%4! A thousand plateaus* capitalism and schi,ophrenia, trans! B! *ass#mi! 5ondon6 Eontin##m! /l#sser, H! &;;;! The shape of things* a philosophy of design! 5ondon6 >ea$tion! /rampton, ! &;;B! -tudies in tectonic culture* the poetics of construction in nineteenth and twentieth century architecture! Eambridge, *ass!6 *'( Lress! Gibson, K! K! &;=;! The ecological approach to &isual perception! Boston6 ?o#ghton *ifflin! Glad,in, (! &;F4! E#lt#re and logical process! 'n %xplorations in cultural anthropology, ed! 7! ?! Goodeno#gh! -e, Yor$6 *cGra,+?ill, pp! &F=+==! ?eidegger, *! &;=&! .oetry/ language/ thought, trans! A! ?ofstadter! -e, Yor$6 ?arper and >o,! 'ngold, (! 2%%%! *a$ing c#lt#re and ,eaving the ,orld! 'n Matter/ materiality and modern culture, ed! L! Graves+Bro,n! 5ondon6 >o#tledge, pp! 324+332! 'ngold, (! 2%%=! Lines* a brief history! 5ondon6 >o#tledge! 'ngold, (! 2%&&! Being ali&e* essays on mo&ement/ knowledge and description! 5ondon6 >o#tledge!

2F

lee, L! &;=3! !oteboooks/ &olume 0* The nature of nature, trans! ?! -orden, ed! K! Spiller! 5ondon6 5#nd ?#mphries! 5Ivi+Stra#ss, E! &;BB! Tristes tropi)ues, trans! K! and D! 7eightman! 5ondon 6 Konathan Eape! *ac$, K! 2%%=! (he land vie,ed from the sea! A,ania* Archaeological 1esearch in Africa 42.&06 &+&4! Cl,ig, ! 2%%<a! Lerforming on landscape vers#s doing landscape6 peramb#latory practice, sight and the sense of belonging! 'n Ways of walking* ethnography abd practice on foot, eds! (! 'ngold and K! 5ee Herg#nst! Aldershot6 Ashgate, pp! <&+;&! Cl,ig, ! 2%%<b! (he K#tland cipher6 #nloc$ing the meaning and po,er of a contested landscape! 'n !ordic landscapes* region and belonging on the northern edge of %urope, eds! *! Kones and ! >! Cl,ig! *inneapolis6 University of *innesota Lress, pp! &2+4;! >ybc8yns$i, 7! &;<;! The most beautiful house in the world! -e, Yor$6 Leng#in! Schama, S! &;;B! Landscape and memory! 5ondon6 ?arperEollins! Semper, G! .&;<;0 Style in the technical and techtonic arts or practical aesthetics .&<F%0, in The $our %lements of Architecture and Other Writings, trans! ?! /! *allgrave and 7! ?errman! Eambridge6 Eambridge University Lress!

2=

Fig!re

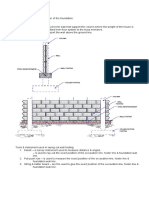

/ig#re & (he conical lodge, vie,ed from the o#tside, in the gro#nds of the *#se#m! (he people standing beside it give an idea of the scale Mperhaps ,e sho#ld say ,ho they are, and give some more details of the provenance of this partic#lar tentN

/ig#re 2 5oo$ing #p thro#gh the ape1 of the tent, the linear poles inter,eave to comprise a comple1 $not, from ,hich each nevertheless contin#es, reaching #p into the open s$y!

2<

You might also like

- Easy CellarDocument88 pagesEasy Cellar9pbdqm8zq2No ratings yet

- Of Mother Nature and Marlboro Men: An Inquiry Into The Cultural Meanings of Landscape PhotographyDocument12 pagesOf Mother Nature and Marlboro Men: An Inquiry Into The Cultural Meanings of Landscape PhotographyPeterNorthNo ratings yet

- Building AS400 Application With Java-Ver 2Document404 pagesBuilding AS400 Application With Java-Ver 2Rasika JayawardanaNo ratings yet

- Masonry Design Guide 3Document568 pagesMasonry Design Guide 3Nemanja Randelovic100% (2)

- What Is Your Road, Man?Document232 pagesWhat Is Your Road, Man?Oana AndreeaNo ratings yet

- Sentimental Fabulations, Contemporary Chinese Films: Attachment in the Age of Global VisibilityFrom EverandSentimental Fabulations, Contemporary Chinese Films: Attachment in the Age of Global VisibilityRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- File ManagementDocument16 pagesFile ManagementAyrha paniaoan100% (1)

- Allegra Fryxell - Viewpoints Temporalities - Time and The Modern Current Trends in The History of Modern Temporalities - TEXT PDFDocument14 pagesAllegra Fryxell - Viewpoints Temporalities - Time and The Modern Current Trends in The History of Modern Temporalities - TEXT PDFBojanNo ratings yet

- Carman - The Body in Husserl and Merleau-PontyDocument22 pagesCarman - The Body in Husserl and Merleau-PontyRené AramayoNo ratings yet

- Traditions British Columbias IndiansDocument166 pagesTraditions British Columbias IndiansValdemar RamírezNo ratings yet

- Aguiluz-Ibargüen 2014Document27 pagesAguiluz-Ibargüen 2014Cristian CiocanNo ratings yet

- Wetland PDFDocument40 pagesWetland PDFAashrity ShresthaNo ratings yet

- 2 Betwixt and Between Identifies Liminal Experience in ContemporaryDocument18 pages2 Betwixt and Between Identifies Liminal Experience in ContemporaryAmelia ReginaNo ratings yet

- The Iconography of LandscapeDocument8 pagesThe Iconography of LandscapeforoughNo ratings yet

- Temporalisation of ConceptsDocument9 pagesTemporalisation of ConceptsJean Paul RuizNo ratings yet

- Time Traveling Dogs (And Other Native Feminist Ways To Defy Dislocations)Document7 pagesTime Traveling Dogs (And Other Native Feminist Ways To Defy Dislocations)ThePoliticalHatNo ratings yet

- Barbara ZDocument19 pagesBarbara ZSergio M.No ratings yet

- Natura Environmental Aesthetics After Landscape Etc Z-LibDocument297 pagesNatura Environmental Aesthetics After Landscape Etc Z-LibBeatrice Catanzaro100% (1)

- Unfinished The Anthropology of BecomingDocument50 pagesUnfinished The Anthropology of BecomingqueeranthroNo ratings yet

- Religion and Material Culture: Matter of BeliefDocument13 pagesReligion and Material Culture: Matter of BeliefrafaelmaronNo ratings yet

- Painter - "Territory-Network"Document39 pagesPainter - "Territory-Network"c406400100% (1)

- The Concept of Action and Responsibility in Heideggers Early ThoughtDocument201 pagesThe Concept of Action and Responsibility in Heideggers Early ThoughtNadge Frank AugustinNo ratings yet

- Chavin12 LRDocument19 pagesChavin12 LRDiogo BorgesNo ratings yet

- Concepts of Perception, Visual Practice, and Pattern Art Among The Cashinahua Indians (Peruvian Amazon Area) .Document23 pagesConcepts of Perception, Visual Practice, and Pattern Art Among The Cashinahua Indians (Peruvian Amazon Area) .Guilherme MenesesNo ratings yet

- Progress and The Nature of CartographyDocument12 pagesProgress and The Nature of CartographyAmir CahanovitcNo ratings yet

- Postmodern Voices of Tricksters and Bear Spirits and Heritage in Gerald Vizenor's LiteratureDocument8 pagesPostmodern Voices of Tricksters and Bear Spirits and Heritage in Gerald Vizenor's LiteratureESTHER OGODONo ratings yet

- Angels Cosma Ioana I 200911 PHD ThesisDocument295 pagesAngels Cosma Ioana I 200911 PHD Thesispavnav72No ratings yet

- East Coast Greenway Guide CT RIDocument100 pagesEast Coast Greenway Guide CT RINHUDLNo ratings yet

- Johannes FabianDocument152 pagesJohannes FabianMurilo GuimarãesNo ratings yet

- Peter Furst - DolmatoffDocument7 pagesPeter Furst - DolmatoffDavid Fernando CastroNo ratings yet

- Marisol de La Cadena - Indigenous CosmopoliticsDocument37 pagesMarisol de La Cadena - Indigenous CosmopoliticsJosé RagasNo ratings yet

- Are You 'Avin A Laff' A Pedagogical Response To Bakhtinian Carnivalesque in Early Childhood Education (2) - AnnotatedDocument17 pagesAre You 'Avin A Laff' A Pedagogical Response To Bakhtinian Carnivalesque in Early Childhood Education (2) - AnnotatedHo TENo ratings yet

- Unbinding Vision - Jonathan CraryDocument25 pagesUnbinding Vision - Jonathan Crarybuddyguy07No ratings yet

- Author's VoiceDocument33 pagesAuthor's VoiceAnonymous d5SioPTNo ratings yet

- KEIGHTLEY, E. e PICKERING, M. "The Modalities of Nostalgia'" PDFDocument24 pagesKEIGHTLEY, E. e PICKERING, M. "The Modalities of Nostalgia'" PDFSabrina MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Critical Analysis of "Cemeteries As Outdoor Museums"Document12 pagesCritical Analysis of "Cemeteries As Outdoor Museums"johnikgNo ratings yet

- Strathern, M. Reading Relation BackwardsDocument17 pagesStrathern, M. Reading Relation BackwardsFernanda HeberleNo ratings yet

- Antczak Et Al. (2017) Re-Thinking The Migration of Cariban-Speakers From The Middle Orinoco River To North-Central Venezuela (AD 800)Document45 pagesAntczak Et Al. (2017) Re-Thinking The Migration of Cariban-Speakers From The Middle Orinoco River To North-Central Venezuela (AD 800)Unidad de Estudios ArqueológicosNo ratings yet

- An Archaeology of Materials. Substantial Transformations in Early Prehistoric Europe - Chantal ConnellerDocument169 pagesAn Archaeology of Materials. Substantial Transformations in Early Prehistoric Europe - Chantal ConnellerJavier Martinez EspuñaNo ratings yet

- Playing With PoverDocument13 pagesPlaying With PoveremiliosasofNo ratings yet

- Ritual, Anti-Structure, and Religion A Discussion of Victor Turners Processual SymbolicDocument26 pagesRitual, Anti-Structure, and Religion A Discussion of Victor Turners Processual SymbolicRita FernandesNo ratings yet

- Cosmic Clows, Convention, Invention, and Inversion in The Yaqui Easter RitualDocument217 pagesCosmic Clows, Convention, Invention, and Inversion in The Yaqui Easter RitualMateus ZottiNo ratings yet

- Mind in MatterDocument20 pagesMind in MatterFernanda_Pitta_5021No ratings yet

- DivergenceDocument320 pagesDivergenceSofia100% (1)

- The City As ArchiveDocument10 pagesThe City As ArchiveKannaNo ratings yet

- Marks, Laura U. - Video Haptics and EroticsDocument26 pagesMarks, Laura U. - Video Haptics and EroticsZiyuan TaoNo ratings yet

- Gow - An Amazonian Myth and Its History PDFDocument182 pagesGow - An Amazonian Myth and Its History PDFSonia Lourenço100% (3)

- Michel de Certeau's HeterologyDocument11 pagesMichel de Certeau's HeterologyWelton Nascimento100% (1)

- Hugh Jones - Writing On Stone Writing On PaperDocument30 pagesHugh Jones - Writing On Stone Writing On PaperAdriana Michelle Paez GilNo ratings yet

- Dennis Tedlock - On The Translation of Style in Oral NarrativeDocument21 pagesDennis Tedlock - On The Translation of Style in Oral NarrativeJamille Pinheiro DiasNo ratings yet

- Andean AestheticsDocument9 pagesAndean AestheticsJime PalmaNo ratings yet

- 63 3 KeelingDocument15 pages63 3 KeelingWackadoodleNo ratings yet

- Alberti-Bray - Animating Archaeology - of Subjects, Objects and Alternative OntologiesDocument8 pagesAlberti-Bray - Animating Archaeology - of Subjects, Objects and Alternative OntologiesFiorella LopezNo ratings yet

- Vision, Race, and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image WorldFrom EverandVision, Race, and Modernity: A Visual Economy of the Andean Image WorldRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- Povinelli-Do Rocks ListenDocument15 pagesPovinelli-Do Rocks ListenMuhammadNo ratings yet

- Marisol de La Cadena - Mario Blaser (Eds.) - A World of Many Worlds-Duke University Press (2018) PDFDocument233 pagesMarisol de La Cadena - Mario Blaser (Eds.) - A World of Many Worlds-Duke University Press (2018) PDFBarbaraBartlNo ratings yet

- 'Many Paths To Partial Truths': Archives, Anthropology, and The Power of RepresentationDocument12 pages'Many Paths To Partial Truths': Archives, Anthropology, and The Power of RepresentationFernanda Azeredo de Moraes100% (1)

- Legendary hunters: The whaling indians: West Coast legends and stories — Part 9 of the Sapir-Thomas Nootka textsFrom EverandLegendary hunters: The whaling indians: West Coast legends and stories — Part 9 of the Sapir-Thomas Nootka textsNo ratings yet

- Origin of the wolf ritual: The whaling indians: West Coast legends and stories — Part 12 of the Sapir-Thomas Nootka textsFrom EverandOrigin of the wolf ritual: The whaling indians: West Coast legends and stories — Part 12 of the Sapir-Thomas Nootka textsNo ratings yet

- Vertiginous Life: An Anthropology of Time and the UnforeseenFrom EverandVertiginous Life: An Anthropology of Time and the UnforeseenNo ratings yet

- Jbcaa Study GuideDocument6 pagesJbcaa Study GuideYerramsetti VenkateshNo ratings yet

- Space Description: Spatial Identification and Staffing RequirementDocument3 pagesSpace Description: Spatial Identification and Staffing RequirementJosielyn ArrezaNo ratings yet

- QH GDL 374 3.3Document169 pagesQH GDL 374 3.3Ravi ValiyaNo ratings yet

- BUR SpecificationDocument5 pagesBUR SpecificationajuciniNo ratings yet

- Hindu Newspaper Case Study IBM ImplementationDocument4 pagesHindu Newspaper Case Study IBM ImplementationDivyansh GuptaNo ratings yet

- Sample M.tech Thesis ContentsDocument85 pagesSample M.tech Thesis ContentsAvancha VasaviNo ratings yet

- Oracle Big Data Appliance - SW - GuideDocument64 pagesOracle Big Data Appliance - SW - GuideMudiare UjeNo ratings yet

- Working of Coa and IiaDocument7 pagesWorking of Coa and IiaKaranKayasth100% (1)

- HMT - Aluminator 1000 - BrochureDocument2 pagesHMT - Aluminator 1000 - BrochureJorge ZumaranNo ratings yet

- Sips Erection GuideDocument12 pagesSips Erection GuideKalibabaNo ratings yet

- Sacred 2 Ica & Blood ManualDocument64 pagesSacred 2 Ica & Blood ManualwladimirkNo ratings yet

- No SQL Not Only SQL: Table of ContentDocument12 pagesNo SQL Not Only SQL: Table of ContentTushar100% (1)

- FLORIDA DrainageManualDocument105 pagesFLORIDA DrainageManualHelmer Edgardo Monroy GonzálezNo ratings yet

- Oracle HCM Presales and Sales TestDocument40 pagesOracle HCM Presales and Sales TestSergio Martinez50% (2)

- CA - Ex - S2M01 - Introduction To Routing and Packet Forwarding - PPT (Compatibility Mode)Document100 pagesCA - Ex - S2M01 - Introduction To Routing and Packet Forwarding - PPT (Compatibility Mode)http://heiserz.com/No ratings yet

- Design Features and Architecture: Facade of TowerDocument1 pageDesign Features and Architecture: Facade of TowerHarinder KaurNo ratings yet

- LM 430 ManualDocument8 pagesLM 430 ManualMilind PatilNo ratings yet

- Masonry 9Document5 pagesMasonry 9Shaina Freya Grantoza NasolNo ratings yet

- Deploying Oracle RAC 11g With ASM On AIX With XIVDocument28 pagesDeploying Oracle RAC 11g With ASM On AIX With XIVkaka_wangNo ratings yet

- P2LPC Users Manual PDFDocument34 pagesP2LPC Users Manual PDFFatihDutaAlamsyahNo ratings yet

- LRFD Compression Member DesignDocument242 pagesLRFD Compression Member DesignMochammad ShokehNo ratings yet

- A Guided Tour of Joomla's Configuration - PHP FileDocument17 pagesA Guided Tour of Joomla's Configuration - PHP FileAhmed El-attarNo ratings yet

- Need For Speed UndercoverDocument2 pagesNeed For Speed UndercoverMohit BorakhadeNo ratings yet

- PORTSHOW - Tips and Tricks: GuysDocument22 pagesPORTSHOW - Tips and Tricks: GuysGopinath VenkateshNo ratings yet

- 355 Painter - 736762 - 736762 - 3551Document3 pages355 Painter - 736762 - 736762 - 3551Siniša BrkićNo ratings yet

- Kundereisen Med Sap Hybris Meet The ExpertDocument13 pagesKundereisen Med Sap Hybris Meet The ExpertManindra TiwariNo ratings yet