Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Clin Diabetes 2014 Beverly 12 7

Clin Diabetes 2014 Beverly 12 7

Uploaded by

rahayumartaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Clin Diabetes 2014 Beverly 12 7

Clin Diabetes 2014 Beverly 12 7

Uploaded by

rahayumartaCopyright:

Available Formats

F E A T U R E

A R T I C L E

Older Adults Perceived Challenges With Health Care Providers Treating Their Type 2 Diabetes and Comorbid Conditions

Elizabeth A. Beverly, PhD, Linda A. Wray, PhD, Ching-Ju Chiu, PhD, and Cynthia L. LaCoe, BA ype 2 diabetes is one of the most significant and growing chronic health problems in the United States. It is marked by the bodys inability to make insulin, as well as the bodys inability to effectively use the insulin it produces.1 Diagnosis of type 2 diabetes has increased sharply in recent decades2 and is expected to increase even more dramatically, with the largest increase in adults 75 years of age.3 Diabetes is the seventh leading cause of death in the United States, despite often being underreported on death certificates. Furthermore, diabetes-related costs to society represent 23% of current health care expenditures, with more than half attributable to adults 65 years of age.4 Although prevention of type 2 diabetes is the ultimate goal, more effective management for individuals already diagnosed is crucial to mitigating the risk of complications and reducing the economic burden of the disease. More than one in four U.S. adults 65 years of age have diabetes,1 with the vast majority having type 2 diabetes. Diabetes treatment for older adults necessitates special attention to the clinical (e.g., comorbidities and complications) and functional (e.g., impairments and disabilities) characteristics of this population. Most adults with type 2 diabetes have at least one comorbid condition,5 and as many as 40% have three or more distinct condi-

tions.6 Older adults with diabetes also are at greater risk for geriatric syndromes, including depression, cognitive impairment, injurious falls, neuropathic pain, and urinary incontinence.3,7 Comorbidities and complications can have a negative impact on diabetes self-care,811 health status, and quality of life.12,13 Furthermore, comorbidities and complications that do not directly affect self-care may pose competing demands, requiring substantial time, effort, and money to manage effectively.1417 As part of a larger qualitative study exploring how older adults manage and cope with type 2 diabetes self-care and other chronic

IN BRiEF

conditions,17 we present here an emergent theme of older adults perceived challenges with the providers treating their multiple health conditions. Study Methods Research design We conducted eight 60-minute focus groups with 32 older adults diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and at least one other chronic health condition; each focus group included two to six participants. Focus groups are a qualitative technique in which data are collected through semi-structured group interviews.18 We used focus groups to gain insight into older adults experiences about the care they receive for type 2 diabetes and comorbid conditions. Sample selection We employed purposive sampling19 to recruit community-dwelling adults who were English-speaking, mentally alert, 60 years of age, diagnosed with type 2 diabetes by a doctor at least 1 year ago, and diagnosed with one or more chronic conditions in addition to diabetes. Participants were excluded if they were diagnosed with Alzheimers disease, other dementia, stroke, or cancer in the past year, severe psychopathology (schizophrenia or bipolar disorder), or alcohol or drug abuse or if they had impaired activities of daily living (e.g., if they answered yes to the question

Type 2 diabetes and comorbidity represent serious health problems to the aging population. This qualitative study aimed to describe older adults perceived challenges with providers treating their type 2 diabetes and other chronic conditions. Older adults perceived a general unwillingness from their providers to treat their multiple health conditions and address their individual preferences for care. Older adults may require more in-depth communication with their providers in addition to individualized treatment plans that address their preferences for comorbidity management.

12

Volume 32, Number 1, 2014 CLINIcAL DIABETES

F E A T U R E

A R T I C L E

Do you have any difficulties with bathing, dressing, personal hygiene, or walking?). Participants with impaired activities of daily living were excluded because the aim of this study was to explore the impact of multiple chronic health conditions on type 2 diabetes self-management; if participants were receiving assistance with activities of daily living, they also may have been receiving assistance with diabetes self-care behaviors such as medication taking and meal planning and preparation. Participants were recruited via the university diabetes database and direct mailings and flyers in the community. We contacted potential participants via telephone to screen them for eligibility and collect data on their sociodemographic characteristics. The university institutional review board approved the study. All participants provided written informed consent before participation and received compensation for their time. Data collection We devised a structured discussion guide and field-tested it for flow and clarity of the questions with a group of four participants. Once the discussion guide was finalized, we began data collection. Focus groups were conducted at community sites (recreational centers and churches), university conference rooms, and occasionally at geriatric outpatient clinics. A trained moderator asked participants broad, open-ended questions about their perceived challenges of managing type 2 diabetes amid multiple chronic conditions, how they coped with potentially interacting conditions, and whether they perceived some conditions as more severe or important than others. Co-moderators observed focus groups and wrote field notes to capture key points (i.e., written

accounts of what happened during focus groups) and observations (e.g., participant affect and behaviors) about the discussions. At the end of each focus group, moderators and co-moderators met to share impressions and observations. Focus group discussions were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim; names and identifiers were removed to protect confidentiality. Data analysis Data analysis in qualitative research is an iterative process in which data collection and data analysis occur concurrently. For this study, the multidisciplinary research team, consisting of two gerontologists, a health behaviorist, and a graduate student, analyzed data using standard qualitative techniques.19 Specifically, the researchers performed content analysis by independently marking and categorizing key words, phrases, and texts to identify codes to describe the overarching themes.20 Transcripts were coded and then reviewed to resolve discrepancies. This process continued until saturation was reached, that is, until no new codes emerged. After all transcripts were coded and reviewed, one member of the research team entered the coded transcripts in NVivo 8 software (QSR International, Victoria, Australia) to organize the data to support thematic analysis. To support credibility (validity), we triangulated data sources and investigators.21 We converged multiple data sources, including focus group discussions, participant observation (e.g., participant affect and behaviors), and field notes (i.e., written accounts of what happened during focus groups) to verify the consistency of our findings.21 Furthermore, two experienced researchers outside the research team and four participants reviewed

the findings to achieve researcher and participant corroboration.22 To support dependability (reliability) of the data, we tracked the decision-making process using an audit trail.21 The audit trail is a detailed description of the research steps conducted from the development of the project to the presentation of findings. Study Results Thirty-two older adults with type 2 diabetes participated in one of eight focus groups (71.3 7.6 years of age, A1C 6.9 0.8%, diabetes duration 13.3 10.7 years, BMI 32.5 6.7 kg/ m2, 44% male, 100% non-Hispanic white, 52% college education or greater, 60% married, 84% retired [Table 1]). The six most commonly reported chronic conditions other than diabetes were hypertension (n = 23), arthritis (n = 19), retinopathy (n = 15), hypercholesterolemia (n = 12), coronary artery disease (n = 8), and neuropathy (n = 8). Previously published findings17 from this focus group study of 32 older adults with type 2 diabetes and other chronic conditions identified three themes: 1) diabetes complications as a motivator, 2) prioritizing health conditions, and 3) emotional impact of comorbidity management. The majority of older adults perceived some of their comorbid conditions as being more serious than their diabetes and selectively attended to diabetes self-care based on perceived severity or importance. These older adults also reported distress and uncertainty when integrating multiple self-care behaviors for interacting conditions. Furthermore, they described feeling frustrated and overwhelmed with the multiple lifestyle, self-care, and medical demands required to manage their diabetes and other chronic comorbidities. Despite these difficulties, they acknowledged that the

CLINIcAL DIABETES Volume 32, Number 1, 2014

13

F E A T U R E

A R T I C L E

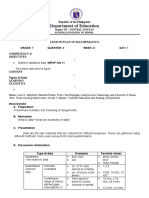

Table 1. Study Participants Demographic and Health Characteristics Variable A1C (%)** Diabetes duration (years) Health conditions including diabetes (n) BMI (kg/m2)** Age (years) Education (years) Prescribed oral hypoglycemic medication(s) (%)** Prescribed insulin injections (%)** Female (%) White (%) Married (%) Retired (%) *Data presented are means SD or percentages. **Based on self-report. threat or onset of diabetes-specific complications motivated them to improve their diabetes self-care. Importantly, an unexpected yet prominent theme emerged specific to older adults experiences with the health care providers (HCPs) treating their diabetes and chronic comorbid conditions. We discuss this emergent theme and provide relevant quotations below (transcript identifiers accompany each quotation indicating each sources identification number, sex (M/F), focus group (FG) number, age, and number of health conditions). Theme: older adults perceived challenges with HCPs Older participants felt that their diabetes providers (31 of 32 specifically referred to their physicians) did not understand or appreciate the difficulties of living with type 2 diabetes and other chronic health conditions. For example, many (18 of 32 participants) perceived a general unwillingness from their providers to treat their diabetes and comorbid conditions: I dont know if its because of my other problems, but to me as soon as the doctors find that you have diabetes, they dont want to take care of you. If I have a cut on my finger, they dont want to take care of it because Im diabetic. It seems like as soon as they find out youre diabetic, whatever your problem is, they dont want to take care of it because youre diabetic. Thats the way I feel about it. They told me that there was surgery for spinal stenosis, but they wont do the surgery because Im diabetic. It makes me feel terrible. It feels like Im never going to have anything done for me because I am diabetic. None of the doctors will want to take care of my problems. I think theyre worried about complications and malpractice. But they arent looking out for my best interests. [#7F, FG 3, age 68, 4 health conditions] Mean* (n = 32) 7.0 0.8 15.0 12.6 5.2 1.7 29.9 6.5 75.3 7.4 14.6 2.8 87.5 46.9 56.3 100.0 71.9 93.8 Range 5.68.2 250 39 19.848.8 6088 920

Others (23 of 32) described experiences of limited support and empathy from their providers. Specifically, they felt that their type 2 diabetes providers were insensitive to their older age and remaining years of life: In the beginning of October, I was told that I had had two heart attacks. Every time the doctor came to see me, he kept telling me that I was going to die. He said, Now you had two heart attacks and pretty soon, youre just in a waiting position, youll be getting another heart attack, and thats going to take you. That was horrible thing to hear! I finally waited until I couldnt take it anymore. I said to him, You know, I think God isnt ready for me yet in heaven. He thinks theres something that I can still accomplish during my lifetime. And until God decides he wants me, nobody else is going to take me down! [#32F, FG 8, age 84, 8 health conditions] Several participants (11 of 32) attributed this perceived lack of support and empathy to age discrimination. Two women verbalized their frustration with their providers in the following dialogue: Sometimes I find that when doctors are treating someone my age, they say, Well youre not forty youre closer to death so we wont treat you as aggressively as we would treat someone else. [#6F, FG 2, age 87, 4 health conditions] Yeah, its very upsetting. Theyre always telling me that Im doing great, and yet I know how Im feeling. Ill be 82 in July; I think I ought to know my own body by then. [laughing] And I know that I dont feel as good as they say I do. I think doctors discriminate against older people in that respect. They say that youre okay, and youre not. [#5F, FG 2, age 81, 8 health conditions]

14

Volume 32, Number 1, 2014 CLINIcAL DIABETES

F E A T U R E

A R T I C L E

Furthermore, many participants felt that their providers did not address their individual preferences for care. These participants wanted their providers to take the time to listen to their difficulties with multiple health conditions, as well as their preferences for specific treatments: Sometimes you have to talk to your doctor, especially if you have multiple health concerns. . . . I wish they would give you more time to say what you want to say to them. To me, its just not the same anymore. I only go because of my medicine; otherwise I wouldnt go to the doctor. [#12F, FG 4, age 83, 4 health conditions] I want the doctor to listen more. I remember when I got the diabetes. I was told maybe in the future you can go off the insulin and go with [oral] medication. I think I control mine pretty good. And whenever I go, I mention it to him, I hear the old story Everything is working right. Dont rock the boat! I would really like to go on an oral medication or pill rather than sticking myself all the time. You stick yourself in the arms, and after a while you have to move to your middle and then your thighs. After a while youre just sore all over. [#13M, FG 4, age 74, 3 health conditions] Some participants (20 of 32) also felt that their care was not individualized to address their specific medical history. These participants wanted their diabetes providers to tailor treatment prescriptions and recommendations to meet their individual needs: My experience has been, you walk into an endocrinologists office, and everyone is treated pretty much the same. And the doctor wants to be the one with all the answers. And that may not be right for the person who is well-educated, proactive, and wants to go out there and see what they can do

on their own. [#2F, FG 1, age 66, 5 health conditions] I wish I could exercise. And the doctor says exercise, but I cant exercise. I do this [demonstrates moving arms forwards and backwards] and move my arms, but to me thats not exercise. I used to walk all the time, and now I cant with the spinal stenosis and arthritis . . . . I dont know what to do about it. They [physicians] just dont want to understand that I cant exercise. I can walk a little bit with a walker but not very far like only a couple of steps. Thats not exercise. Its moving, but its not exercising. But they dont tell me what I can do about it. [#7F, FG 3, age 68, 4 health conditions] Finally, several older adults (10 of 32) expressed frustration with the care they received during hospital stays. They felt that the hospital health care team did not listen to their concerns about high blood glucose levels or provide the necessary medication adjustments to improve their blood glucose control: My experience in the hospital is that they are very naive about diabetes and what being in the hospital does to your blood sugar without anything else. When youre in there and youre taking medications, your blood sugar, mine really went very high. I told them I wanted to be regulated, but they were reluctant to give me what I thought I needed. And they didnt. I had to make a big fuss for them to try and take it seriously. Its happened to me a couple of times, and Ive seen it happen to others. [#27M, FG 7, age 83, 7 health conditions] Ive been in for surgery a few times, and of course your sugar goes out of whack because of the stress of it all. Its over 200, and they give me 2 units of insulin! Whats this 2 units? I take 20 in the morning and 20 at night. Why are you giving me

2? I take 20. [#26F, FG 7, age 73, 5 health conditions] I take Lantus, which is a longterm insulin. You normally inject it once a day, and the level goes up, but theres no peak. It stays that way around the clock for about 24 hours until you take another shot. Im taking 20 units of Lantus. In the hospital the doctor said, The sugar is doing something. Were going to give you another shot of Lantus at 12 hours. He didnt understand what Lantus does. That was absolutely clear, he didnt know. [#28M, FG 8, age 79, 6 health conditions] Discussion In this qualitative study of 32 older adults with type 2 diabetes and other chronic conditions, participants felt that their HCPs did not understand or appreciate the difficulties of living with type 2 diabetes and other chronic health conditions. Many perceived a general unwillingness from their providers to treat their diabetes along with their comorbid conditions. These adults described experiences of limited support and empathy from their providers, which some attributed to age discrimination. Furthermore, participants felt that their providers did not address their individual preferences for care. They wanted their providers to take the time listen to their difficulties with multiple health conditions, as well as their preferences for specific treatments, particularly during hospital stays. These findings suggest a potential disconnect in the provider-patient treatment relationship with older adults with type 2 diabetes and comorbidities. Successful diabetes care requires teamwork between providers and patients.23 Two components of successful teamwork are provider-patient communication and shared decision-making, both of which have been shown to

CLINIcAL DIABETES Volume 32, Number 1, 2014

15

F E A T U R E

A R T I C L E

improve patient satisfaction, adherence to treatment plans, and health outcomes.2431 As adults with type 2 diabetes age, the health-related challenges they face can get more complicated and personal.32 For this reason, older adults may require more in-depth communication with their HCPs, in addition to individualized treatment plans that address their preferences for comorbidity management. Older adults and their HCPs should engage in ongoing discussions about what care is best for them and why. Furthermore, incorporating older adults preferences regarding type 2 diabetes and comorbidity treatments can have important effects on the cost-effectiveness of glycemic control.33 Thus, discussing perceived challenges to diabetes and comorbidity management may provide a systematic way to include older adults in the evaluation and treatment process, thereby enhancing the therapeutic alliance34 and lowering the economic burden of type 2 diabetes care. In our study, the older adults felt that their HCPs did not understand or appreciate the difficulties of living with type 2 diabetes and other chronic health conditions. However, two recent qualitative studies with primary care providers found that providers acknowledged the complexities of comorbidity management and stressed the importance of a patient-centered approach to care, emphasizing individualization and shared decision-making.35,36 Importantly, these providers spoke of conflicts between balancing patients preferences with their own decisions for care and weighing the risks and benefits of adhering to treatment guidelines.36 Thus, HCPs and older adults may benefit from education and clinical tools that target shared decisionmaking and communication skills

to build an interactive relationship in which both HCPs and adults are comfortable addressing the challenges of diabetes and comorbidity management. Study limitations include homogeneity of the study sample with regard to race/ethnicity and residential status (community-dwelling), participant self-selection, and selfreported data. The all-white, highly educated sample is representative of the central Pennsylvania area in which the data were collected. For this reason, cultural and social variations regarding older adults experiences with the HCPs treating their diabetes and chronic comorbid conditions warrant further study. Furthermore, this sample was in relatively good glycemic control (mean A1C 7.0 0.8%, range 5.68.2%), which may have influenced their responses during the focus groups. For example, an older adult with a higher A1C level (e.g., 10%) may perceive different challenges with their HCPs that were not discussed in our focus groups. Thus, perspectives of older adults with a wider range of glycemic control are needed. Additionally, we did not conduct focus groups with older adults with type 1 diabetes and other chronic comorbidities. These individuals may experience unique challenges managing multiple health conditions that are not reflected in our sample of older adults with type 2 diabetes. Furthermore, the use of selfreported diagnoses may have introduced error. Older adults may have confused symptoms and minor ailments with more significant diseases; likewise, they may have forgotten to report important health diagnoses. Additionally, our study did not include focus groups from the provider perspective. Future research with a larger, more heterogeneous

sample should involve the collection of mixed-method data from physician-patient pairs to assess communication and shared decisionmaking regarding type 2 diabetes and comorbidity management. Finally, the findings from this study are exploratory and should be considered hypotheses. In conclusion, type 2 diabetes and comorbidity represent serious health care problems to the aging population. Understanding the differential impact of diabetes and comorbid conditions requires careful consideration when treating older adults, and more research is needed to explore physicians and patients perspectives on preferences for comorbidity management. HCPs may not always discuss preferences with their patients; however, our findings provide reason for HCPs to consider older adults preferences in the treatment of multiple chronic health conditions. Furthermore, considering that the Affordable Care Act encourages shared decisionmaking in health care, inquiring about older adults preferences for care has become even more important for providers to integrate into their clinical practice.3739 Strategies that facilitate a mutual understanding of treatment preferences may help providers and older adults with type 2 diabetes manage multiple health conditions more effectively and with greater peace of mind. AcKNOWLEdGmENt The authors thank the older adults who participated in this study and shared their experiences managing their multiple chronic health conditions. This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging [T32 AG00048 to S.L.W]; the Pennsylvania State Graduate Alumni Association Dissertation Award; and the Ed and Helen Hintz

16

Volume 32, Number 1, 2014 CLINIcAL DIABETES

F E A T U R E

A R T I C L E

Award for Outstanding Graduate Work in the Department of Biobehavioral Health. REFErENcEs

Centers for Disease Conrol and Prevention: National diabetes fact sheet: national estimates and general information on diabetes and prediabetes in the United States, 2011.Atlanta, Ga., U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2011. Accessed 24 April 2013 Beckles GL, Zhu J, Moonesinghe R: DiabetesUnited States, 2004 and 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 60:9093, 2011

3 Kirkman MS, Briscoe VJ, Clark N, Florez H, Haas LB, Halter JB, Huang, ES, Korytkowski MT, Munshi MN, Odegard PS, Pratley RE, Swift CS: Diabetes in older adults. Diabetes Care 35:26502664, 2012 4 American Diabetes Association: Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care 36:10331046, 2013 5 Druss BG, Marcus SC, Olfson M, Tanielian T, Elinson L, Pincus HA: Comparing the national economic burden of five chronic conditions. Health Aff (Millwood) 20:233241, 2001 6 Wolff JL, Starfield B, Anderson G: Prevalence, expenditures, and complications of multiple chronic conditions in the elderly. Arch Intern Med 162:22692276, 2002 2 1

model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. J Fam Pract. 38:166171, 1994

15 Chernof BA, Sherman SE, Lanto AB, Lee ML, Yano EM, Rubenstein LV: Health habit counseling amidst competing demands: effects of patient health habits and visit characteristics. Med Care 37:738747, 1999 16 Bayliss EA, Steiner JF, Fernald DH, Crane LA, Main DS: Descriptions of barriers to self-care by persons with comorbid chronic diseases. Ann Fam Med 1:1521, 2003 17 Beverly EA, Wray LA, Chiu CJ, Weinger K: Perceived challenges and priorities in comorbidity management of older patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med 28:781784, 2011 18 Krueger RA, Casey MA: Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif., Sage Publications, 2000 19 Morse JM, Field PA: Qualitative Research Methods for Health Professionals. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif., Sage Publications, 1995 20 Krippendorf K: Content Analysis: An Introduction to Its Methodology. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif., Sage Publications, 2004 21 Miles M, Huberman A: Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, Calif., Sage Publications, 1994 22 Denzin N: The Research Act: A Theoretical Introduction to Sociological Methods. 2nd ed. New York, McGraw-Hill, 1978 23 Heisler M, Vijan S, Anderson RM, Ubel PA, Bernstein SJ, Hofer TP: When do patients and their physicians agree on diabetes treatment goals and strategies, and what difference does it make? J Gen Intern Med 18:893902, 2003 24 Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE Jr., Yano EM, Frank HJ: Patients participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med 3:448457, 1988

observational study. Qual Saf Health Care 12:273279, 2003

30 Piette JD, Schillinger D, Potter MB, Heisler M: Dimensions of patient-provider communication and diabetes self-care in an ethnically diverse population. J Gen Intern Med. 18:624633, 2003 31 Kerr EA, Smith DM, Kaplan SH, Hayward RA: The association between three different measures of health status and satisfaction among patients with diabetes. Med Care Res Rev 60:158177, 2003 32 Blaum CS: Management of diabetes mellitus in older adults: are national guidelines appropriate? J Am Geriatr Soc 50:581583, 2002 33 Huang ES, Shook M, Jin L, Chin MH, Meltzer DO: The impact of patient preferences on the cost-effectiveness of intensive glucose control in older patients with newonset diabetes. Diabetes Care 29:259264, 2006 34 Huang ES, Gorawara-Bhat R, Chin MH: Practical challenges of individualizing diabetes care in older patients. Diabetes Educ 30:558, 560, 562, 2004 35 Luijks HD, Loeffen MJ, Lagro-Janssen AL, van Weel C, Lucassen PL, Schermer TR: GPs considerations in multimorbidity management: a qualitative study. The Br J Gen Pract 62:e503e510, 2012 36 Fried TR, Tinetti ME, Iannone L: Primary care clinicians experiences with treatment decision making for older persons with multiple conditions. Arch Intern Med 171:7580, 2011 37 Oshima Lee E, Emanuel EJ: Shared decision making to improve care and reduce costs. N Engl J Med 368:6-8, 2013 38 Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S: Shared decision making--pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med 366:780781, 2012 39 Truog RD: Patients and doctors: evolution of a relationship. N Engl J Med 366:581585, 2012

Brown AF, Mangione CM, Saliba D, Sarkisian CA: Guidelines for improving the care of the older person with diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc 51(5 Suppl.):S265S280, 2003 Ciechanowski PS, Katon WJ, Russo JE: Depression and diabetes: impact of depressive symptoms on adherence, function, and costs. Arch Intern Med 160:32783285, 2000

9 Schoenberg NE, Drungle SC: Barriers to non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) self-care practices among older women. J Aging Health.13:443466, 2001 10 Krein SL, Heisler M, Piette JD, Makki F, Kerr EA: The effect of chronic pain on diabetes patients self-management. Diabetes Care 28:6570, 2005 8

Greenfield S, Kaplan S, Ware JE Jr.: Expanding patient involvement in care: effects on patient outcomes. Ann Intern Med 102:520528, 1985

26 Anderson RM, Funnell MM, Butler PM, Arnold MS, Fitzgerald JT, Feste CC: Patient empowerment: results of a randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care 18:943949, 1995 27 Von Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH: Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med 127:10971102, 1997 28 Campbell SM, Hann M, Hacker J, Burns C, Oliver D, Thapar A, Mead N, Safran DG, Roland MO: Identifying predictors of high quality care in English general practice: observational study. BMJ. 323:784787, 2001 29 Bower P, Campbell S, Bojke C, Sibbald B: Team structure, team climate and the quality of care in primary care: an

25

Kerr EA, Heisler M, Krein SL, Kabeto M, Langa KM, Weir D, Piette JD: Beyond comorbidity counts: how do comorbidity type and severity influence diabetes patients treatment priorities and self-management? J Gen Intern Med 22:16351640, 2007

12 Glasgow RE, Ruggiero L, Eakin EG, Dryfoos J, Chobanian L: Quality of life and associated characteristics in a large national sample of adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 20:562567, 1997 13 Wray LA, Ofstedal MB, Langa KM, Blaum CS: The effect of diabetes on disability in middle-aged and older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 60:12061211, 2005

11

Jaen CR, Stange KC, Nutting PA: Competing demands of primary care: a

14

Elizabeth A. Beverly, PhD, is an assistant professor of social medicine at the Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine in Athens, Ohio. Linda A. Wray, PhD, is an associate professor of biobehavioral health, and Cynthia L. LaCoe, BA, is a graduate student in biobehavioral health at Pennsylvania State University in University Park. Ching-Ju Chiu, PhD, is an assistant professor of gerontology at National Cheng Kung University, in Tainan, Taiwan.

CLINIcAL DIABETES Volume 32, Number 1, 2014

17

You might also like

- Pre Trial Order Civil CaseDocument3 pagesPre Trial Order Civil Casejennylynne73% (11)

- Three Questions (Q&A)Document3 pagesThree Questions (Q&A)saran ks50% (2)

- Language Register Formal, Informal, and NeutralDocument29 pagesLanguage Register Formal, Informal, and NeutralDavid SamuelNo ratings yet

- The Role of Patient, Physician and Systemic Factors in The Management of Type 2 Diabetes MellitusDocument6 pagesThe Role of Patient, Physician and Systemic Factors in The Management of Type 2 Diabetes MellitusAmaniNo ratings yet

- Factors Associated With Self-Care Behavior of Elderly Patients With Type 2Document4 pagesFactors Associated With Self-Care Behavior of Elderly Patients With Type 2audy saviraNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion DiabetesDocument20 pagesHealth Promotion Diabetesharshotsai100% (1)

- Estado Del Arte TesisDocument3 pagesEstado Del Arte Tesistgey7890No ratings yet

- Diabetes Distress Healthcare ProvidersDocument8 pagesDiabetes Distress Healthcare ProvidersMaria HorvathNo ratings yet

- Problem Solving and Diabetes Self-Management: Investigation in A Large, Multiracial SampleDocument5 pagesProblem Solving and Diabetes Self-Management: Investigation in A Large, Multiracial SampleAndreea MadalinaNo ratings yet

- D Barriers To Improved Diabetes Management: Results of The Cross-National Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) StudyDocument13 pagesD Barriers To Improved Diabetes Management: Results of The Cross-National Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) StudyDanastri PrihantiniNo ratings yet

- 2017 2804178 PDFDocument9 pages2017 2804178 PDFahlamNo ratings yet

- Perceived Barriers and Effective Strategies To Diabetic Self-ManagementDocument18 pagesPerceived Barriers and Effective Strategies To Diabetic Self-ManagementArceeJacobaHermosaNo ratings yet

- Increasing Diabetes Self-Management Education in Community SettingsDocument2 pagesIncreasing Diabetes Self-Management Education in Community Settingsmuhammad ade rivandy ridwanNo ratings yet

- Diabetik Dan KelainannyaDocument11 pagesDiabetik Dan Kelainannyalatifah zahrohNo ratings yet

- Health Beliefs, Self-Care Behaviors and Quality of Life in Adults With Type 2 DiabetesDocument9 pagesHealth Beliefs, Self-Care Behaviors and Quality of Life in Adults With Type 2 DiabetesgamzeNo ratings yet

- Coping Styles Among Adults With Type 1 and Type 2 DiabetesDocument15 pagesCoping Styles Among Adults With Type 1 and Type 2 DiabetesErikaNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Distress Paper EfmjDocument16 pagesDiabetes Distress Paper EfmjAhmed NabilNo ratings yet

- How Did I Feel Before Becoming Diabetes Resilience? A Qualitative Study in Adult Type 2 Diabetes MellitusDocument8 pagesHow Did I Feel Before Becoming Diabetes Resilience? A Qualitative Study in Adult Type 2 Diabetes Mellitusyuliaindahp18No ratings yet

- Kid 0004662020Document8 pagesKid 0004662020Rian KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Integrative Review Paper 1Document12 pagesRunning Head: Integrative Review Paper 1api-296425490No ratings yet

- 259 PDFDocument6 pages259 PDFbgvtNo ratings yet

- Community Program Improves Quality of Life and Self-Management in Older Adults With Diabetes Mellitus and ComorbidityDocument11 pagesCommunity Program Improves Quality of Life and Self-Management in Older Adults With Diabetes Mellitus and ComorbidityZhafirah SalsabilaNo ratings yet

- Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & ReviewsDocument5 pagesDiabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & ReviewsPetra Diansari ZegaNo ratings yet

- Assessing The ProblemDocument10 pagesAssessing The ProblemKeyvoh KeymanNo ratings yet

- Hypertensive Patients Knowledge, Self-Care ManagementDocument10 pagesHypertensive Patients Knowledge, Self-Care ManagementLilian ArthoNo ratings yet

- DNHE4 Project Proposal 2201393222Document17 pagesDNHE4 Project Proposal 2201393222Surya Dharshni HomoeoNo ratings yet

- What's Distressing About Having Type 1 DiabetesDocument14 pagesWhat's Distressing About Having Type 1 DiabetesTengku EltrikanawatiNo ratings yet

- An 014100Document14 pagesAn 014100Lino Gomila SepúlvedaNo ratings yet

- Managing Multiple Comorbidities - UpToDateDocument15 pagesManaging Multiple Comorbidities - UpToDateGaby GarcésNo ratings yet

- Boggiss (2023) - Improving The Well-Being of Adolescents With TypeDocument15 pagesBoggiss (2023) - Improving The Well-Being of Adolescents With TypeSebastian FitzekNo ratings yet

- NIDDK International Conference Report On Diabetes and Depression: Current Understanding and Future DirectionsDocument11 pagesNIDDK International Conference Report On Diabetes and Depression: Current Understanding and Future Directionsyeremias setyawanNo ratings yet

- DM in ElderlyDocument44 pagesDM in ElderlyMamang BagiansahNo ratings yet

- Alcohol Related Problems Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesAlcohol Related Problems Literature Reviewafmzetkeybbaxa100% (1)

- Format PengkajianDocument8 pagesFormat PengkajianHandiniNo ratings yet

- Changes in Attitudes Toward Mental Illness in Healthcare Professionals and StudentsDocument14 pagesChanges in Attitudes Toward Mental Illness in Healthcare Professionals and StudentsleticiaNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Artigo EdDocument15 pagesDiabetes Artigo EdEduarda CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- CaídasDocument5 pagesCaídasRocio ConsueloNo ratings yet

- - Qualitative and quantitative studies (インドネシアの農村地域における2型糖尿病患者の糖尿病 知識、健康信念、および保健行動 研究)Document6 pages- Qualitative and quantitative studies (インドネシアの農村地域における2型糖尿病患者の糖尿病 知識、健康信念、および保健行動 研究)CM GabriellaNo ratings yet

- Blok 22 TugasDocument22 pagesBlok 22 TugasUlva HirataNo ratings yet

- HipertensiDocument9 pagesHipertensinurmaliarizkyNo ratings yet

- An Overview of The Rationale For Qualitative Research Methods in Social HealthDocument3 pagesAn Overview of The Rationale For Qualitative Research Methods in Social Healthapolinarioeser04No ratings yet

- Coping Strategies and Blood Pressure Control Among Hypertensive Patients in A Nigerian Tertiary Health InstitutionDocument6 pagesCoping Strategies and Blood Pressure Control Among Hypertensive Patients in A Nigerian Tertiary Health Institutioniqra uroojNo ratings yet

- Association Between Health LiteraDocument8 pagesAssociation Between Health LiteraberthaNo ratings yet

- Nature 2011 Global Mental HealthDocument4 pagesNature 2011 Global Mental HealthcogidaNo ratings yet

- Waiting For Diabetes Perceptions of People With Pre-DiabetesDocument6 pagesWaiting For Diabetes Perceptions of People With Pre-DiabetesitomoralesNo ratings yet

- Providing Diabetes Education To Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease: A Survey of Diabetes Educators in Ontario, CanadaDocument10 pagesProviding Diabetes Education To Patients With Chronic Kidney Disease: A Survey of Diabetes Educators in Ontario, CanadaKritik KumarNo ratings yet

- Enfermedades Prevalentes Del Paciente GeriatricoDocument15 pagesEnfermedades Prevalentes Del Paciente GeriatricoMilton FabianNo ratings yet

- K Burns Qualitative Research PosterDocument1 pageK Burns Qualitative Research Posterapi-257576036No ratings yet

- Diabetes Prevention Knowledge and Perception of Risk AmongDocument7 pagesDiabetes Prevention Knowledge and Perception of Risk AmongMuhammad AgussalimNo ratings yet

- Group 10 Chapter I IIIDocument26 pagesGroup 10 Chapter I IIIJogil ParaguaNo ratings yet

- DMT2Document19 pagesDMT2darianajuarezaracasNo ratings yet

- Self Management Experiences Among Men and WomenDocument12 pagesSelf Management Experiences Among Men and Womenirene1991No ratings yet

- Effectiveness of SMDocument27 pagesEffectiveness of SMHarismaPratamaNo ratings yet

- Global Dimensions of Diabetes Information and Syn 2015 Annals of Global HeaDocument2 pagesGlobal Dimensions of Diabetes Information and Syn 2015 Annals of Global HeaarmanNo ratings yet

- Diabete Online CommunityDocument12 pagesDiabete Online CommunityMary SueNo ratings yet

- Barriers To Self-Management and Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Seniors With MultimorbiditiesDocument8 pagesBarriers To Self-Management and Quality-of-Life Outcomes in Seniors With MultimorbiditiesZarna PatelNo ratings yet

- Lin 2012Document7 pagesLin 2012Ferdy LainsamputtyNo ratings yet

- Heakth Care InterventionDocument7 pagesHeakth Care InterventionChukwuka ObikeNo ratings yet

- Artikel Pubmed 3Document6 pagesArtikel Pubmed 3Sofa AmaliaNo ratings yet

- Type 2 DiabetesDocument13 pagesType 2 DiabetesElenaMatsneva100% (1)

- Jurnal Keperawatan ARS UniversityDocument31 pagesJurnal Keperawatan ARS Universityratna jobsNo ratings yet

- Literature Review UpdatedDocument7 pagesLiterature Review Updatedapi-392259592No ratings yet

- Rethinking Diabetes: Entanglements with Trauma, Poverty, and HIVFrom EverandRethinking Diabetes: Entanglements with Trauma, Poverty, and HIVNo ratings yet

- EDUC 101 - Course Syllabus: Department of Teacher EducationDocument14 pagesEDUC 101 - Course Syllabus: Department of Teacher EducationKyla DamaliNo ratings yet

- Ultra320 Scsi UmDocument70 pagesUltra320 Scsi UmChandan SharmaNo ratings yet

- MDFakeBooksCat PDFDocument34 pagesMDFakeBooksCat PDFbaba0% (1)

- Part 1 - Question EmailsDocument6 pagesPart 1 - Question Emailsyennhi yennhiNo ratings yet

- Fisiologi Sistem Saraf TepiDocument19 pagesFisiologi Sistem Saraf TepiNata NayottamaNo ratings yet

- Reading Hormonal Changes During PregnancyDocument6 pagesReading Hormonal Changes During PregnancyKlinik Asy syifaNo ratings yet

- CD MneumonicDocument9 pagesCD Mneumonicgaa5No ratings yet

- Savage Worlds Quick Player ReferenceDocument2 pagesSavage Worlds Quick Player Referencesbroadwe100% (1)

- Apply The Word Sample Book of (Matthew) - NKJV PDFDocument60 pagesApply The Word Sample Book of (Matthew) - NKJV PDFTuan Pu100% (1)

- Estructurar Un Monólogo PDFDocument4 pagesEstructurar Un Monólogo PDFpablo_658No ratings yet

- Chapter - 1 Stress Management: An IntroductionDocument27 pagesChapter - 1 Stress Management: An IntroductionAfsha AhmedNo ratings yet

- The Reasons Why Family Is So Much Important in Our LifeDocument4 pagesThe Reasons Why Family Is So Much Important in Our LifeLara Jane DogoyNo ratings yet

- Green Goffee FOB, G & F, CIF Contract: Specialty Coffee Association of AmericaDocument4 pagesGreen Goffee FOB, G & F, CIF Contract: Specialty Coffee Association of AmericacoffeepathNo ratings yet

- Sebastian vs. BajarDocument12 pagesSebastian vs. BajarAnisah AquilaNo ratings yet

- Meta Ads Video FrameworkDocument4 pagesMeta Ads Video FrameworkFakhzan BadiranNo ratings yet

- Department of Education: Lesson Plan in MathematicsDocument2 pagesDepartment of Education: Lesson Plan in MathematicsShiera SaletreroNo ratings yet

- 6 Type of Management Styles For Effective LeadershipDocument39 pages6 Type of Management Styles For Effective LeadershipEvaa MayfaNo ratings yet

- U.S. v. Wilson, Appellate Court Opinion, 6-30-10Document115 pagesU.S. v. Wilson, Appellate Court Opinion, 6-30-10MainJusticeNo ratings yet

- Anvar P.V. v. P.K. Basheer & Ors - The Cyber Blog IndiaDocument1 pageAnvar P.V. v. P.K. Basheer & Ors - The Cyber Blog IndiaPravesh SatraNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Asset Allocation - IbbotsonDocument4 pagesThe Importance of Asset Allocation - IbbotsonRyan GohNo ratings yet

- 12 - Chapter 4 PDFDocument21 pages12 - Chapter 4 PDFIba KharmutiNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Studies SSC-II Model Question PaperDocument6 pagesPakistan Studies SSC-II Model Question PaperAbdul RiazNo ratings yet

- Jordan Curve TheoremDocument5 pagesJordan Curve Theoremmenilanjan89nLNo ratings yet

- Agilent N9360A Multi UE Tester: GSM User ManualDocument354 pagesAgilent N9360A Multi UE Tester: GSM User ManualTewodros YimerNo ratings yet

- Constant Selection Bi ReportingDocument10 pagesConstant Selection Bi ReportinggiacurbanoNo ratings yet

- Technological Institute of The Philippines Quezon City Civil Engineering Department Ce407Earthquake Engineering Prelim ExaminationDocument7 pagesTechnological Institute of The Philippines Quezon City Civil Engineering Department Ce407Earthquake Engineering Prelim ExaminationGerardoNo ratings yet

- Cpa Reading ListDocument6 pagesCpa Reading ListIddy MohamedNo ratings yet