Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Bookrags Literature Criticism: Critical Essay by Catherine Gallagher

Bookrags Literature Criticism: Critical Essay by Catherine Gallagher

Uploaded by

Suhad Jameel JabakCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Life in A Love: Poem Text Poem Text Themes ThemesDocument9 pagesLife in A Love: Poem Text Poem Text Themes ThemesSuhad Jameel Jabak0% (1)

- Aristophanes - Assemblywomen (Barrett)Document52 pagesAristophanes - Assemblywomen (Barrett)Docteur LarivièreNo ratings yet

- Rape of The LockDocument5 pagesRape of The LockShaimaa SuleimanNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare's RomancesDocument5 pagesShakespeare's RomancesMaria DamNo ratings yet

- The Taming of the Shrew (Annotated by Henry N. Hudson with an Introduction by Charles Harold Herford)From EverandThe Taming of the Shrew (Annotated by Henry N. Hudson with an Introduction by Charles Harold Herford)Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1711)

- Beginning Theory StudyguideDocument29 pagesBeginning Theory StudyguideSuhad Jameel Jabak80% (5)

- Business Games Teaching EnglishDocument79 pagesBusiness Games Teaching Englishladyreveur97% (31)

- Module in Criminal Law Book 2 (Criminal Jurisprudence)Document11 pagesModule in Criminal Law Book 2 (Criminal Jurisprudence)felixreyes100% (3)

- Absurd Drama - Martin EsslinDocument10 pagesAbsurd Drama - Martin EsslinSimone MottaNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical Movere in Hamlet: Student: Alexiu Adela-Elena Major: ChineseDocument4 pagesRhetorical Movere in Hamlet: Student: Alexiu Adela-Elena Major: ChineseAdela AlexiuNo ratings yet

- Othello As Tragic HeroDocument5 pagesOthello As Tragic Heroapi-300710390100% (1)

- The Theory of the Theatre, and Other Principles of Dramatic CriticismFrom EverandThe Theory of the Theatre, and Other Principles of Dramatic CriticismNo ratings yet

- The Masks of Othello: The Search for the Identity of Othello, Iago, and Desdemona by Three Centuries of Actors and CriticsFrom EverandThe Masks of Othello: The Search for the Identity of Othello, Iago, and Desdemona by Three Centuries of Actors and CriticsNo ratings yet

- Saint Joan As A Tragegic HeroDocument8 pagesSaint Joan As A Tragegic Herovkumar_345287100% (4)

- FRYE Characterization in Shakespearian ComedyDocument8 pagesFRYE Characterization in Shakespearian Comedycecilia-mcdNo ratings yet

- The Best Short Stories of Edgar Allan Poe (Illustrated by Harry Clarke with an Introduction by Edmund Clarence Stedman)From EverandThe Best Short Stories of Edgar Allan Poe (Illustrated by Harry Clarke with an Introduction by Edmund Clarence Stedman)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- Compilation John DonneDocument27 pagesCompilation John DonneHasan KurbanNo ratings yet

- Essay LitDocument5 pagesEssay Litb.espin.sanchezNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of The Famous Poem When You Are OldDocument6 pagesAn Analysis of The Famous Poem When You Are Oldanon_919669374No ratings yet

- The WaltzDocument4 pagesThe WaltzИгорь ГромNo ratings yet

- Dfadf ShakespeareDocument12 pagesDfadf Shakespeareapi-242119616No ratings yet

- Stories and StorytellingDocument3 pagesStories and StorytellingRoy Boffey100% (2)

- Literary TermsDocument6 pagesLiterary TermsLee MeiNo ratings yet

- The Circus Animals-SummaryDocument8 pagesThe Circus Animals-SummaryJuliusNo ratings yet

- Notes On CampDocument12 pagesNotes On CampmadaandreeaNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare's Plays: TragedyDocument2 pagesShakespeare's Plays: TragedyAhsan AliNo ratings yet

- Theatre of The AbsurdDocument7 pagesTheatre of The AbsurdAnamaria OnițaNo ratings yet

- Absurd EsslinDocument14 pagesAbsurd EsslinChristopher Daniel Serna RuizNo ratings yet

- 06 - Chapter 1 PDFDocument30 pages06 - Chapter 1 PDFPIYUSH KUMARNo ratings yet

- Staging The Puppet Show in Bartholomew FairDocument20 pagesStaging The Puppet Show in Bartholomew FairRose-Marie WaltonNo ratings yet

- The Theatre of The AbsurdDocument10 pagesThe Theatre of The AbsurdMais MirelaNo ratings yet

- Irony in World DramasDocument7 pagesIrony in World DramasResearch ParkNo ratings yet

- 18th Century DramaDocument2 pages18th Century DramaPaulescu Daniela AnetaNo ratings yet

- The Tempest - Epilogue CriticismsDocument2 pagesThe Tempest - Epilogue CriticismsMiss_M9050% (4)

- The Raven - Symbolism and Unity of EffectDocument10 pagesThe Raven - Symbolism and Unity of Effectdenerys2507986No ratings yet

- The Futurist Cinema, 1916Document5 pagesThe Futurist Cinema, 1916elise_mourikNo ratings yet

- OCG Essay On Scene 6Document2 pagesOCG Essay On Scene 6Beth KingNo ratings yet

- The Theatre of The AbsurdDocument14 pagesThe Theatre of The AbsurdAyushman ShuklaNo ratings yet

- CH 02Document35 pagesCH 02towsenNo ratings yet

- Drama AssignmentDocument15 pagesDrama AssignmentLakshaySharmaNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 06 Sep 2021Document9 pagesAdobe Scan 06 Sep 2021gopikaNo ratings yet

- A Collection of Short FictionDocument152 pagesA Collection of Short FictiondraykidNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare and The Art of Mise en Abyme L3Document3 pagesShakespeare and The Art of Mise en Abyme L3chevallierNo ratings yet

- The Wise Fool in Shakespeares PlaysDocument91 pagesThe Wise Fool in Shakespeares PlaysIonutSilviuNo ratings yet

- Ode On A Grecian UrnDocument5 pagesOde On A Grecian UrnAslı As100% (1)

- On Waste Land Analysis All PoemDocument55 pagesOn Waste Land Analysis All PoemNalin HettiarachchiNo ratings yet

- Xxxtraducere Beckett& IonescoDocument7 pagesXxxtraducere Beckett& IonescoEugenia Maria PaşcaNo ratings yet

- Origins of Drama in The African Context FreeDocument10 pagesOrigins of Drama in The African Context FreeLuciaNo ratings yet

- Ode On A Grecian UrnDocument3 pagesOde On A Grecian UrneἈλέξανδροςNo ratings yet

- Twelfth Night Term Paper TopicsDocument7 pagesTwelfth Night Term Paper Topicsafdtwadbc100% (1)

- Theatrical Convention and Audience Response in Early Modern Drama (J Lopez)Document249 pagesTheatrical Convention and Audience Response in Early Modern Drama (J Lopez)Mike MorrisNo ratings yet

- Arms & The ManDocument76 pagesArms & The ManMaruf HossainNo ratings yet

- TheatreDocument8 pagesTheatreRazaw HamdiNo ratings yet

- Characterstics of Elizabethan DramaDocument2 pagesCharacterstics of Elizabethan DramaEsther BuhrilNo ratings yet

- Abstracts On Marcel AntonioDocument6 pagesAbstracts On Marcel AntonioMarcel AntonioNo ratings yet

- Brooke 1964 - The Characters of DramaDocument11 pagesBrooke 1964 - The Characters of DramaPatrick DanileviciNo ratings yet

- Samuel Taylor ColeridgeDocument8 pagesSamuel Taylor Coleridgeapi-300603674No ratings yet

- Course Objectives: SLO #4,5 and 8:: DE. Use Strategies For Independent Learning Apply Critical Thinking Skills ContextDocument4 pagesCourse Objectives: SLO #4,5 and 8:: DE. Use Strategies For Independent Learning Apply Critical Thinking Skills ContextSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- Formalism: Object-Centered Theory Focus Only On The Work Itself Do Not Focus On The Artist of The Observer/audienceDocument6 pagesFormalism: Object-Centered Theory Focus Only On The Work Itself Do Not Focus On The Artist of The Observer/audienceSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- Application Activity Using The PassiveDocument1 pageApplication Activity Using The PassiveSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- Bookrags Literature Study Guide: All My Sons by Arthur MillerDocument41 pagesBookrags Literature Study Guide: All My Sons by Arthur MillerSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- Gendered MediaDocument11 pagesGendered MediaSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- AlchemistDocument20 pagesAlchemistSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- Put The Verb Into The Correct FormDocument3 pagesPut The Verb Into The Correct FormSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- History of ESL Teaching MethodsDocument3 pagesHistory of ESL Teaching MethodsSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- She Said He Said Credibility and Sexual HarassmentDocument11 pagesShe Said He Said Credibility and Sexual HarassmentNatalia AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Saqifa Bani Sa'idahDocument2 pagesSaqifa Bani Sa'idahShadabul HaqueNo ratings yet

- RSS-China MOU?Document3 pagesRSS-China MOU?cbcnnNo ratings yet

- 2012-07-26 HK Magazine - Hong Kong's Expensive Wine IndustryDocument5 pages2012-07-26 HK Magazine - Hong Kong's Expensive Wine IndustryspikescellarNo ratings yet

- Resume Project CoordinatorDocument1 pageResume Project CoordinatorRamesh KumarNo ratings yet

- AS-Live LogDocument3 pagesAS-Live LogarteadNo ratings yet

- 1.18.2024 SBFCC Create Morre Eopt Beps 2.0Document70 pages1.18.2024 SBFCC Create Morre Eopt Beps 2.0b86120298alexlinNo ratings yet

- In The Court of The City Civil Judge at Bangalore (Cch-3)Document7 pagesIn The Court of The City Civil Judge at Bangalore (Cch-3)Erika HarrisNo ratings yet

- Philokalia: Kallos "Beauty") Is "A Collection of Texts Written Between The 4th and 15th Centuries by Spiritual Masters"Document10 pagesPhilokalia: Kallos "Beauty") Is "A Collection of Texts Written Between The 4th and 15th Centuries by Spiritual Masters"estudosdoleandro sobretomismoNo ratings yet

- SEO Proposal For Pakiza - DocxDocument6 pagesSEO Proposal For Pakiza - Docx67Rampur BaghelanNo ratings yet

- AdvertisementsDocument9 pagesAdvertisementsSashi Raj100% (2)

- On Early Christian ExegesisDocument39 pagesOn Early Christian Exegesisasher786No ratings yet

- Reading IN Philippine History: Prepared By: Aiza S. Rosalita, LPT Bsba InstructorDocument100 pagesReading IN Philippine History: Prepared By: Aiza S. Rosalita, LPT Bsba InstructorRanzel SerenioNo ratings yet

- Macro PresentationDocument15 pagesMacro PresentationBeing indianNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis On Bumrungrad' Global SDocument8 pagesCase Analysis On Bumrungrad' Global SSahil AnujNo ratings yet

- SEC Primary RegistrationDocument13 pagesSEC Primary RegistrationElreen Pearl AgustinNo ratings yet

- Un/une Le/la/les Du/de La /desDocument2 pagesUn/une Le/la/les Du/de La /desleprachaunpixNo ratings yet

- English Grammar ExerciseDocument8 pagesEnglish Grammar ExerciseLeonardo Jr PinedaNo ratings yet

- Angie Ucsp Grade 12 w3Document6 pagesAngie Ucsp Grade 12 w3Princess Mejarito MahilomNo ratings yet

- DIG - Vir Jen Shipping and Marine Services Vs NLRC 1983 Case DigestDocument4 pagesDIG - Vir Jen Shipping and Marine Services Vs NLRC 1983 Case DigestKris OrenseNo ratings yet

- Assignemnt 1 - 3 MarksDocument3 pagesAssignemnt 1 - 3 MarksHafsa HayatNo ratings yet

- Biosketch Form and SampleDocument2 pagesBiosketch Form and Sampleapi-313957091No ratings yet

- Individual Assignment 1 - GMDocument10 pagesIndividual Assignment 1 - GMIdayuNo ratings yet

- Reflective ReportDocument6 pagesReflective ReportZulkifli Che HusinNo ratings yet

- Candidate List 64CCE 10-09-2018 OAPDocument115 pagesCandidate List 64CCE 10-09-2018 OAPOm PrakashNo ratings yet

- Amulya Garg DmbaDocument27 pagesAmulya Garg DmbaAsha SoodNo ratings yet

- Cherniss - The Platonism of Gregory of NyssaDocument96 pagesCherniss - The Platonism of Gregory of Nyssa123Kalimero100% (1)

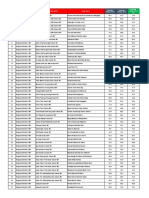

- No. Branch (Mar 2022) Legal Name Organization Level 4 (1 Mar 2022) Average TE/day, 2019 Average TE/day, 2020 Average TE/day, 2021 (A)Document7 pagesNo. Branch (Mar 2022) Legal Name Organization Level 4 (1 Mar 2022) Average TE/day, 2019 Average TE/day, 2020 Average TE/day, 2021 (A)Irfan JauhariNo ratings yet

- A Historical Perspective On Light Infantry: 1ST Special Service Force, Part 10 of 12Document12 pagesA Historical Perspective On Light Infantry: 1ST Special Service Force, Part 10 of 12Bob CashnerNo ratings yet

Bookrags Literature Criticism: Critical Essay by Catherine Gallagher

Bookrags Literature Criticism: Critical Essay by Catherine Gallagher

Uploaded by

Suhad Jameel JabakOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Bookrags Literature Criticism: Critical Essay by Catherine Gallagher

Bookrags Literature Criticism: Critical Essay by Catherine Gallagher

Uploaded by

Suhad Jameel JabakCopyright:

Available Formats

BookRags Literature Criticism

Critical Essay by Catherine Gallagher

For the online version of BookRags' Critical Essay by Catherine Gallagher Literature Criticism, including complete copyright information, please visit http !!"""#bookrags#com!criticism!behn$aphra$%&'(%&)*!+!

Copyright Information

,-((.$-((& /homson Gale, a part of the /homson Corporation# 0ll rights reserved# ,-((($-(%' BookRags, 1nc# 0LL R1G2/3 RE3ER4E5#

Critical Essay by Catherine Gallagher 367RCE 89ho 9as that :asked 9oman; /he <rostitute and the <lay"right in the Comedies of 0phra Behn,8 in Women's Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 4ol %., =o# %$>, %*)), pp# ->$'-# Here, Gallagher focuses on /he Lucky Chance, exploring how ehn !created a persona that s"illfully intertwined the age's a#aila$le discourses concerning women, property, selfhood and authorship%! Everyone kno"s that 0phra Behn, England's first professional female author, "as a colosal and enduring embarrassment to the generations of "omen "ho follo"ed her into the literary marketplace# 0n ancestress "hose name had to be lived do"n rather than lived up to, 0phra Behn seemed, in 4irginia 9oolf's metaphor, to obstruct the very passage"ay to the profession of letters she had herself opened# 9oolf e?plains in A &oom of 'ne's 'wn, 8=o" that 0phra Behn had done it, girls could go to their parents and say, @ou need not give me an allo"anceA 1 can make money by my pen# 6f course the ans"er for many years to come "as, @es, by living the life of 0phra BehnB 5eath "ould be betterB and the door "as slammed faster than ever#8 1t is impossible in this brief essay to e?amine all the facets of the scandal of 0phra BehnA her life and "orks "ere alike characteriCed by certain irregular se?ual arrangements# But it is not these that 1 "ant to discuss, for they seem merely incidental, the sorts of things "omen "riters "ould easily dissociate themselves from if they led pure lives and "rote high$minded books# /he scandal 1 "ould like to discuss is, ho"ever, "ith varying degree of appropriateness, applicable to all female authors, regardless of the conduct of their lives or the content of their "orks# 1t is a scandal that 0phra Behn seems Duite purposely to have constructed out of the overlapping discourses of commercial, se?ual, and linguistic e?change# Conscious of her historical role, she introduced to the "orld of English letters the professional "oman "riter as a ne"fangled "hore# /his persona has many functions in Behn's "orks it titillates, scandaliCes, arouses pity, and indicates the vicissitudes of authorship and identity in general# /he author$"hore persona also makes of female authorship per se a dark comedy that e?plores the bond bet"een the liberty the stage offered "omen and their confinement behind both literal and metaphorical viCard masks# /his is the comedy played out, for e?ample, in the prologue to her first play, The Forced Marriage, "here she announces her epoch$making appearance in the ranks of the play"rights# 3he presents her attainment, ho"ever, not as a daring achievement of self$e?pression, but as a ne" proof of the necessary obscurity of the 8public8 "oman# /he prologue presents 0phra Behn's play"righting as an e?tension of her erotic play# 1n it, a male actor pretends to have escaped temporarily the control of the intriguing female play$"rightA he comes on stage to "arn the gallants in the audience of their danger# /his "as a variation on the Restoration convention of betraying the play"right in the <rologue "ith an added se?ual dimension the comic antagonism bet"een play"right and audience becomes a battle in the "ar bet"een the se?es# <lay"righting, "arns the actor, is a ne" "eapon in "oman's amorous arsenal# 3he "ill no longer "ound only through the eyes, through her beauty, but "ill also use "it to gain a more permanent ascendency# 2ere, "oman's play"riting is "holly assimilated to the poetic conventions of amorous battle that normally informed lyric poetry# 1f the male poet had long depicted the conDuering "oman as necessarily chaste, debarring Eand conseDuently debarred fromF the act of se? itself, then his o"n poetry of lyric complaint and pleas for kindness could only be understood as attempts to overthro" the conDueror# <oetry in this lyric tradition is a "eapon in a struggle that takes as its most fundamental ground$rule a "oman's inability to have a truly sexual conDuest for the doing of the deed "ould be the undoing of her po"er#

0phra Behn's first <rologue, stretches this lyric tradition to incorporate theatre# 2o"ever, the "oman's poetry cannot have the same end as the man's# 1ndeed, according to the <rologue, ends, in the sense of terminations, are precisely "hat a "oman's "it is directed against 9omen those charming victors, in "hose eyes Lie all their arts, and their artilleries, =ot being contented "ith the "ounds they made, 9ould by ne" stratagems our lives invade# Beauty alone goes no" at too cheap rates 0nd therefore they, like "ise and politic states, Court a ne" po"er that may the old supply, /o (eep as "ell as gain the victory /hey'll Goin the force of "it to beauty no", 0nd so maintain the right they have in you# 9riting is certainly on a continuum here "ith se?, but instead of leading to the act in "hich the "oman's conDuest is overturned, play"riting is supposed to e?tend the "oman's erotic po"er beyond the moment of se?ual encounter# /he prologue, then, situates the drama inside the conventions of male lyric love poetry but then reverses the chronological relationship bet"een se? and "ritingA the male poet "rites before the se?ual encounter, the "oman bet"een encounters# 3he thereby actually creates the possibility of a "oman's version of se?ual conDuest# 3he "ill not be immediately conDuered and discarded because she "ill maintain her right through her "riting# /he "oman's play of "it is the opposite of foreplayA it is a kind of afterplay specifically designed to prolong pleasure, rescucitate desire and keep a "oman "ho has given herself se?ually from being traded in for another "oman# 1f the "oman is successful in her poetic e?change, the actor "arns the gallants, then they "ill no longer have the freedom of briskly e?changing mistresses 8@ou'll never kno" the bliss of changeA this art Retrieves E"hen beauty fadesF the "andring heart#8 0phra Behn, then, inaugurated her career by taking up and feminiCing the role of the seductive lyric poet# /he drama the audience is about to see is framed by the larger comedy of erotic e?change bet"een a "oman "riter and a male audience# /hat is, this prologue does "hat so many Restoration prologues do, makes of the play a drama "ithin a drama, one series of conventional interactions inside another# But the very elaborateness of this staging of conventions makes the love battle itself Ethe thing supposedly revealedF seem a strategic pose in a some"hat different drama# 0fter all, "hat kind of "oman "ould stage her se?ual desire as her primary motivation; /he ans"er is a "oman "ho might be suspected not to have any a "oman for "hom professions of amorousness and theatrical in authenticity are the same thing a prostitute# Finally, Gust in case anyone in the audience might have missed this analogy, a dramatic interruption occurs, and the prologue stages a debate about the motivation behind all this talk of strategy# /he actor calls attention to the prostitutes in the audience, "ho "ere generally identified by their masks, and characteriCes them as agents of the play"right, Gokingly using their masks to e?pose them as spies in the amorous "ar /he poetess too, they say, has spies abroad, 9hich have dispers'd themselves in every road, 1' th' upper bo?, pit, galleriesA every face @ou find disguis'd in a black velvet case# :y life on'tA is her spy on purpose sent, /o hold you in a "anton complimentA /hat so you may not censure "hat she's "rit, 9hich done they face you do"n 't"as full of "it# 0t this point, an actress comes on stage to refute the suggestion that the poetess's spies and supporters are prostitutes# 3he returns, then, to the conceits linking money and "arfare and thus e?plicitly enacts the denial of prostitution that "as all along implicit in the trope of amorous combat#

7nlike the troop of prostitutes, she claims, 6urs scorns the petty spoils, and do prefer /he glory not the interest of "ar# But yet our forces shall obliging prove, 1mposing naught but constancy in love /hat's all our aim, and "hen "e have it too, 9e'll sacrifice it all to pleasure you# 9hat the last t"o lines make abundantly clear, in ironically Gustifying female promiscuity by the pleasure it gives to men, is that the prologue has given us the spectacle of a prostitute comically denying mercenary motivations# /he poetess like the prostitute is she "ho 8stands out,8 as the etymology of the "ord 8prostitute8 implies, but it is also she "ho is masked# 1ndeed, as the prologue emphasiCes, the prostitute is she "ho stands out by virtue of her mask# /he dramatic masking of the prostitute and the stagey masking of the play"right's interest in money are e?actly parallel cases of theatrical unmasking in "hich "hat is revealed is the parallel itself the play"right is a "hore# /his conclusion, ho"ever, is more comple? than it might at first seem, for the very playfulness of the representation implies a hidden 8real8 "oman "ho must remain unavailable# /he prologue gives t"o e?planations for female authorship, and they are the usual e?cuses for prostitution it alludes to and disclaims the motive of moneyA it claims the motive of love, but in a "ay that makes the claim seem merely strategic# /he author$"hore, then, is one "ho comically stages her lack of self$e?pression and conseDuently implies that her true identity is the sold self's seller# 3he thus indicates an unseeable selfhood through the flamboyant alienation of her language# 2ence 0phra Behn managed to create the effect of an inaccessible authenticity out of the very image of prostitution# 1n doing so, she capitaliCed on a commonplace slur that probably kept many less ingenious "omen out of the literary marketplace# 89hore's the like reproachful name, as poetess$$the luckless t"ins of shame,8 "rote Robert Gould in %&*%# /he eDuation of poetess and 8punk8 Ein the slang of the dayF "as inescapable in the Restoration# 0 "oman "riter could either deny it in the content and form of her publications, as did Catherine /rotter, or she could embrace it, as did 0phra Behn# But she could not entirely avoid it# For the belief that 8<unk and <oesie agree so pat, ! @ou cannot "ell be this, and not be that8 "as held independently of particular cases# 1t rested on the evidence neither of ho" a "oman lived nor of "hat she "rote# 1t "as, rather, an a priori Gudgement applied to all cases of female publication# 0s one of 0phra Behn's biographers, 0ngeline Goreau, has astutely pointed out Hin &econstructing Aphra, %*)(I, the seventeenth$century ear heard the "ord 8public8 in 8publication8 very distinctly, and hence a "oman's publication automatically implied a public "oman# /he "oman "ho shared the contents of her mind instead of reserving them for one man "as literally, not metaphorically, trading in her sexual property# 1f she "ere married, she "as selling "hat did not belong to her, because in mind and $ody she should have given herself to her husband# 1n the seventeenth century, 8publication,8 Goreau tells us, also meant sale due to bankruptcy, and the publication of the contents of a "oman's mind "as tantamount to the publication of her husband's property# 1n %&%>, Lady Carey published Eanonymously, of courseF these lines on marital property rights, publication and female integrity /hen she usurps upon another's right, /hat seeks to be by public language gracedA 0nd tho' her thoughts reflect "ith purest light 2er mind, if not peculiar, is not chaste# For in a "ife it is no "orse to find 0 common body, than a common mind# <ublication, adultery, and trading in one's husband's property "ere all thought of as the same thing as long as female identity, selfhold, remained an indivisible unity# 0s Lady Carey e?plained, the idea of a public mind in a private body threatened to fragment female identity, to destroy its integrated "holeness 9hen to their husbands they themselves do bind,

5o they not "holly give themselves a"ay; 6r give they but their body, not their mind, Reserving that, tho' best, for other's prey; =o, sure, their thought no more can be their o"n 0nd therefore to none but one be kno"n# /he uniDue, unreserved giving of the "oman's self to her husband is the act that keeps her "hole# 6nly in this singular and total alienation does the "oman maintain her complete self$identity# 9e have already seen that it is precisely this ideal of a totaliCed "oman, preserved because wholly given a"ay, that 0phra Behn sacrifices to create a different idea of identity, one comple?ly dependent on the necessity of multiple e?changes# 3he "ho is able to repeat the action of self$ alienation an unlimited number of times is she "ho is constantly there to regenerate, possess, and sell a series of provisional, constructed identities# 3elf$possession, then, and self$alienation are Gust t"o sides of the same coinA the alienation verifies the possession# 1n contrast, the "ife "ho gives herself once and completely disposes simultaneously of self possession and self alienation# 3he has no more property in "hich to trade and is thus rendered "hole by her action# 3he is her "hole, unviolated "omanhood because she has given up possessing herselfA she can be herself because she has given up ha#ing herself# Further, as Lady Carey's lines make clear, if a "oman's "riting is an authentic e?tension of herself, then she cannot have alienable property in that "ithout violating her "holeness# Far from denying these assumptions, 0phra Behn's comedy is based on them# Like her contemporaries, she presented her "riting as part of her se?ual property, not Gust because it "as ba"dy, but because it "as hers# 0s a "oman, all of her properties "ere at least the potential property of anotherA she could either reserve them and give herself "hole in marriage, or she could barter them piecemeal, accepting self$division to achieve self$o"nership and forfeiting the possibility of marriage# 1n this sense, 0phra Behn's implied identity fits into the most advanced seventeenth$ century theories about selfhood it closely resembles the possessive individualism of Locke and 2obbes, in "hich property in one's self both entails and is entailed by the parcelling out and serial alienation of one's self# For property by definition, in this theory, is that "hich is alienable# 0phra Behn's, ho"ever, is a gender specific version of possessive individualism, one constructed in opposition to the very real alternative of staying "hole by renouncing self possession, an alternative that had no legal reality for men in the seventeenth century# Because the husband's right of property "as in the "hole of the "ife, the prior alienation of any part of her had to be seen as a violation of either actual or potential marital propriety# /hat is, a "oman "ho, like 0phra Behn, embraced possessive individualism, even if she "ere single and never bartered her se?ual favors, could only do so "ith a consciousness that she thus contradicted the notion of female identity on "hich legitimate se?ual property relations rested# <ublication, then, Duite apart from the contents of "hat "as published, ipso facto implied the divided, doubled, and ultimately unavailable person "hose female prototype "as the prostitute# By flaunting her self$sale, 0phra Behn embraced the title of "horeA by "riting ba"dy comedies, "hich she then partly disclaimed, she capitaliCed on her supposed handicap# Finally, she even uses this persona to make herself seem the prototypical "riter, and in this effort she certainly seems to have had the cooperation of her male colleagues and competitors# /hus, in the follo"ing poem, 9illiam 9ycherley "ittily ackno"ledges that the se?ual innuendos about 0phra Behn rebound back on the "its "ho make them# /he occasion of the poem "as a rumor that the poetess had gonorrhea# 9ycherley emphasiCes ho" much more public is the 83appho of the 0ge8 than any normal prostitute, ho" much her fame gro"s as she looses her fame, and ho" much cheaper is the rate of the author$"hore than her sister punk# But he also stresses ho" much more po"er the poetess has, since in the "orld of "it as opposed to the "orld of se?ual e?change, use increases desire, and the author$"hore accumulates men instead of being e?changed among them :ore Fame you no"

Esince talk'd of moreF acDuire, 0nd as more <ublic, are more :ens 5esireA =ay, you the more, that you are Clap'd to, no", 2ave more to like you, less to censure you =o" :en enGoy your <arts for 2alf a Cro"n, 9hich, for a 2undred <ound, they scarce had done, Before your <arts "ere, to the <ublic kno"n# 0ppropriately, 9ycherley ends by imagining the "hole London theatrical "orld as a s"eating$house for venereal disease /hus, as your Beauty did, your 9it does no", /he 9omen's envy, :en's 5iversion gro"A 9ho, to be clap'd, or Clap you, round you sit, 0nd, tho' they 3"eat for it, "ill cro"d your <itA 3ince lately you Lay$in, Ebut as they say,F Because, you had been Clap'd another 9ayA But, if'tis true, that you have need to 3"eat, Get, Eif you canF at your =e" <lay, a 3eat# 1f 0phra Behn's se?ual and poetic parts are the same, then the "its are contaminated by her se?ual distemper# 0phra Behn and her fello" "its infect one another the theatre is her body, their "its are their penises, the play is a case of gonorrhea, and the cure is the same as the disease# Given the general Restoration delight in the eDuation of mental, se?ual, and theatrical 8parts,8 and its freDuent likening of "riting to prostitution and play"rights to ba"ds, one might argue that if 0phra Behn had not e?isted, the male play"rights "ould have had to invent her in order to increase the "itty pointedness of their cynical self$representations# For e?ample, in 5ryden's prologue to Behn's The Widow Ranter, the great play"right chides the self$proclaimed "its for contesting the originality of one another's productions and sDuabbling over literary property# 5ra"ing on the metaphor of literary paternity, he concludes But "hen you see these <ictures, let none dare /o o"n beyond a Limb or single shareA For "here the <unk is common, he's a 3ot, 9ho needs "ill father "hat the <arish got# /hese lines gain half their mordancy from their reference to 0phra Behn, the poetess$punk, "hose off$spring cannot seem fully her o"n, but "hose right to them cannot be challenged "ith any propriety# By literaliCing and embracing the play"right$prostitute metaphor, therefore, 0phra Behn "as distinguished from other authors, but only as their prototypical representative# 3he becomes a symbolic figure of authorship for the Restoration, the "riter and the strumpet muse combined# Even those "ho "ished to keep the relationship bet"een "omen and authorship strictly metaphorical "ere fond of the image 89hat a po? have the "omen to do "ith the muses;8 asks a character in a play attributed to Charles Gildon# 81 grant you the poets call the nine muses by the names of "omen, but "hy so; JhellipA because in that se? they're much fitter for prostitution#8 1t is not hard to see ho" much authorial notoriety could be gained by audaciously literaliCing such a metaphor# 0phra Behn, therefore, created a persona that skillfully intert"ined the age's available discourses concerning "omen, property, selfhood and authorship# 3he found advantageous openings "here other "omen found repulsive insultsA she turned self$division into identity# /he authorial effect 1'm trying to describe here should not be confused "ith the plays' disapproving attitudes to"ard turning "omen into items of e?change# The Lucky Chance, "hich 1 am no" going to discuss, all too readily yields a facille, right$minded thematic analysis centering on "omen and property e?change# 1t has three plots that can easily be seen as variations on this theme 5iana is being forced into a loveless marriage "ith a fop because of her father's family ambition# 2er preference for the young Bred"ell is ignored in the e?change# 5iana's father, 3ir Feeble Fain"ood,

is also purchasing himself a young bride, Leticia, "hom he has tricked into believing that her betrothed lover, "ho had been banished for fighting a duel, is dead# Kulia, having already sold herself to another rich old merchant, 3ir Cautious Fulbank, is being "ooed to adultery by her former lover, Gayman# /hat all three "omen are both property and occasions for the e?change of property is Duite clear# 5iana is part of a financial arrangement bet"een the families of the t"o old men, and the intended bridegroom, BearGest, sees her merely as the embodiment of a great fortuneA Leticia is also bought by 8a great Gointure,8 and though "e kno", interestingly, nothing of Kulia's motives, "e are told that she had played such a 8prank8 as Leticia# 1t is very easy, then, to make the point that the treatment of "omen as property is the problem that the play's comic action "ill set out solve# 9hether she marries for property, as in the cases of Leticia and Kulia or she is married as property Ethat is, given, like 5iana, as the condition of a do"eryF, the "oman's identity as a form of property and item of e?change seems obviously to be the play's point of departure, and the urge to break that identification seems, on a casual reading, to license the play's impropriety# 6ne could even redeem the fact that, in the end, the "omen are all gi#en by the old men to their lovers by pointing out that this is, after all, a comedy and hence a form that reDuires female desire to flo" through established channels# 3uch a superficial thematic analysis of )he *uc"y +hance fits in "ell "ith that image of 0phra Behn some of her most recent biographers promote an advocate of 8free love8 in every sense of the phrase and a heroic defender of the right of "omen to speak their o"n desires# 2o"ever, such an interpretation does not bear the "eight of the play's structure or remain steady in the face of its ellipses, nor can it sustain the pressure of the play's images# For the moments of crisis in the play are not those in "hich a "oman becomes property but those in "hich a "oman is burdened "ith a selfhood that can be neither represented Ea self "ithout propertiesF nor e?changed# /hey are the moments "hen the veiled "oman confronts the impossibility of being represented and hence of being desired and hence of being, finally, perhaps, gratified# Before turning to those moments, 1'd like to discuss some larger organiCational features of the play that complicate its treatment of the theme of "omen and e?change# First, then to the emphatic "ay in "hich the plots are disconnected in their most fundamental logic# /he plots of 5iana and Leticia rely on the idea that there is an irreversible moment of matrimonial e?change after "hich the "oman is 8given8 and cannot be given again# /hus the action is directed to"ard th"arting and replacing the planned marriage ceremony, in the case of 5iana, and avoiding the consummation of the marriage bed in the case of Leticia# Kulia, ho"ever, has crossed both these threshholds and is still someho" free to dispose of herself# /he logic on "hich her plot is based seems to deny that there are critical or irremediable events in female destiny# 2ence in the scene directly follo"ing Leticia's intact deliverance from 3ir Feeble Fain"ood's bed and 5iana's elopement "ith Bred"ell, "e find Kulia resignedly urging her aged husband to get the se? over "ith and to stop meddling "ith the affairs of her heart 8But let us leave this fond discourse, and, if you must, let us to bed8# Kulia proves her self$ possession precisely by her indifference to the crises structuring 5iana's and Leticia's e?periences# 6n the one hand, Kulia's plot could be seen to undercut the achievement of resolution in the other plots by implying that there "as never anything to resolve the obstacles "ere not real, the crises "ere not crises, the definitive moment never did and never could arrive# Kulia's "ould be the pervasive atmosphere of comedy that keeps the an?ieties of the more 8serious8 love plot from truly being registered# But on the other hand, "e could argue that the crisis plots drain the adultery plot not only of moral credibility but also of dramatic interest, for there "ould seem to be simply nothing at stake in Kulia's plot# 1ndeed, Kulia's plot in itself seems bent on making this point, turning as it so often does on attempts to achieve things that have already been achieved or gambling for stakes that have already been "on# /hese t"o responses, ho"ever, tend to cancel one another, and "e cannot conclude that either plot logic renders the other nugatory# The Lucky Chance achieves its effects, rather by alternately presenting the problem and its seeming none?istence# /he imminent

danger of becoming an un"illing piece of someone else's property is at once asserted and denied# /he alternating assertion!denial emphasiCes the discontinuity bet"een the t"o 8resolutions8 of the "oman's se?ual identity that 1 discussed earlier one in "hich the giving of the self intact is tantamount to survivalA the other in "hich an identity is maintained in a series of e?changes# /his very discontinuity, then, as 1've already pointed out, is part of an overarching discursive pattern# /he proof of self o"nership is self saleA hence, Kulia has no e?culpating story of deceit or coercion to e?plain her marriage to Fulbank# But the complete import of "hat she does, both of "hat she sacrifices and "hat she gains, can only be understood against the background of a one$time e?change that involves and maintains the "hole self# /he disGunction bet"een the plot e?igencies Leticia is subGected to and those that hold and create Kulia, Eour inability to perceive these plots "ithin a single comic perspectiveF reveals the oppositional relationship bet"een the t"o seventeenth$century versions of the female as property# Built into this very disGunction, therefore, is a complicated presentation of the seeming inescapability for "omen of the condition of property# 1n the play, the e?change of "omen as property appears inevitable, and the action revolves around the terms of e?change# /he crisis plots, of "hich Leticia's is the most important, posit "holeness as the pre$condition of e?change and as the result of its successful completion# /he unitary principle dominates the logic of this plot and also, as "e are about to see, the language of its actors and its representational rules# Kulia's plot, on the other hand, assumes not only the fracturing and multiplication of the self as a condition and result of e?change, but also the creation of a second order of reality a reality of representations through "hich the characters simultaneously alienate and protect their identities# /his split in representational procedures can be detected in the first scene, "here it is associated "ith the characters of the leading men# 1n the play's opening speech, Bellmour enters complaining that the la" has stolen his identity, has made him a creature of disguise and the night# 2is various complaints in the scene cluster around a central fear of de$differentiation, of the failure properly to distinguish essential differences# /hus it is the 8rigid la"s, "hich put no difference ! '/"i?t fairly killing in my o"n defence, ! 0nd murders bred by drunken arguments, ! 9hores, or the mean revenges of a co"ard8 that have forced his disguise, his alienation from his o"n identity# /hat is, the denial of the true, identity insuring, difference Ethat bet"een duelers and murderersF necessitates false differences, disguises and theatrical representations that get more elaborate as the plot progresses# /he comedy is this series of disguises and spectacles, but its end is to render them unnecessary by the reunion of Bellmour "ith his proper identity and his proper "ife# /he very terms of Bellmour's self$alienation, moreover, are identitarian in their assumption that like must be represented by like# Bellmour has taken a life in a duel, and for that he is deprived of the life he thought he "ould lead# 2e has destroyed a body "ith his s"ord, and for that a body that belongs to him, Leticia's, "ill be taken from him also through puncturing# Even the comic details of Bellmour's reported death are consonant "ith this mode of representation R0L<2 2anged, 3ir, hanged, at /he 2ague in 2olland# BELL:67R For "hat, said they, "as he hanged; R0L<2 9hy, e'en for high treason, 3ir, he killed one of their kings# G0@:0= 2olland's a common"ealth, and is not ruled by kings# R0L<2 =ot by one, 3ir, but by many# /his "as a cheesemonger, they fell out over a bottle of brandy, "ent to snicker snee, :r# Bellmour cut his throat, and "as hanged for't, that's all, 3ir# /he reductio ad absurdum of like representing like is the common"ealth in "hich everyone is a king# 1t is "ithin this comically literalist system of representation that Bellmour is imagined to have

had his neck broken for slitting the throat of a cheesemonger# 1t is no "onder that the clima? of Bellmour's performance is a simulation of the e?change of like for like# 0s 3ir Feeble Fain"ood approaches the bed on "hich he intends to deflo"er Leticia, asking her, 89hat, "as it ashamed to sho" its little "hite foots, and its little round bubbies;,8 Belmour comes out from bet"een the curtains, naked to the "aist# 0nd, all the better to "ard off that "hich he represents, he has Leticia's proGected "ound painted on his o"n chest and a dagger ready to make another such "ound on 3ir Feeble# /he "hole representational economy of this plot, therefore, has an underlying unitary basis in the notion that things must be paid for in kind# Even Leticia's self sale seems not to be for money but for the Ge"elry to "hich she is often likened# Like Bellmour, Gayman also enters the first scene in hiding, 8"rapped in his cloak,8 but the functional differences bet"een the t"o kinds of self$concealment are soon manifested# /he end of Gayman's disguises is not the retrieval of his property, but the appropriation of "hat he thinks is the property of others 80re you not to be married, 3ir,8 asks Bellmour# 8=o 3ir,8 returns Gayman, 8not as long as any man in London is so, that has but a handsome "ife, 3ir8# 2is attempts are not to reestablish essential differences, but rather to accelerate the process of dedifferentiation# 8/he bridegroomB8 e?claims Bellmour on first seeing 3ir Feeble# 8Like Gorgon's head he's turned me into stone#8 8Gorgon's head,8 retorts Gayman, 8a cuckold's head, 't"as made to graft upon8# /he diCCying s"iftness "ith "hich Gayman e?tends Bellmour's metaphor speaks the former's desire to destroy the paired stability of e?changes# Looking at the bridegroom's head, Bellmour sees an image of destructive female se?uality, the Gorgon# /hus, the bridegroom represents the all$too$ available se?uality of Leticia# Gayman's "ay of disarming this insight is to deck it "ith horns, to introduce the third term, taking advantage of Leticia's availability to cuckold 3ir Feeble# But for Bellmour this is no solution at all, since it only further collapses the distinction bet"een lover and husband, merging him "ith 3ir Feeble at the moment he alienates his se?ual property 89hat, and let him marry herB 3he that's mine by sacred vo" alreadyB by heaven it "ould be flat adultery in herB8 83he'll learn the trick,8 replies Gayman, 8and practise it the better "ith thee#8 /he destruction of the 8true8 distinctions bet"een husband and lover, cuckold and adulterer, proprietor and thief is the state for "hich Gayman longs# Bellmour's comedy, then, moves to"ard the re$establishment of true difference through the creation of false differencesA Gayman's comedy moves to"ard the erasure of true differences through the creation of false and abstract samenesses# Gayman is in disguise because he cannot bear to let Kulia kno" that he is different from his former self# 2e "ishes to appear before her al"ays the same, to hide the ne" fact of his poverty# 2e tries to get money from his landlady so that he can get his clothes out of hock and therefore disguise himself as himself in order to go on "ooing Kulia# 6n the same principle of the effacement of difference, Gayman later tries to pass himself off as Kulia's husband "hen he, unbekno"nst to her, takes the old man's place in bed# :oreover, Gust as the false differences of Bellmour's comedy conformed to a unitary like$for$like economy of representation, the false samenesses of Gayman's plotting are governed by an economy of representation through difference# /he most obvious e?ample of this is the use of money# :oney in this plot often represents bodies or their se?ual use, and "hat is generally emphasiCed in these e?changes are the differences bet"een the body and money# For e?ample, in the scenes of Gayman's t"o prostitutions Ethe first "ith his landlady and the second "ith his unkno"n admirerF, the difference bet"een the "omen's bodies and the precious metals they can be made to yield is the point of the comedy# /he landlady is herself metamorphosed into iron for the sake of this contrast she is an iron lady "ho emerges from her husband's blacksmith's shop# 3he is then stroked into metals of increasing values as she yields 'postle spoons and caudle cups that then e?change for gold# 2o"ever, Gayman's e?pletives never allo" us to forget that this se?ual alchemy is being practiced on an unsublimatable body that constantly sickens the feigning lover "ith its stink# Even more telling is the continuation of this scene in "hich Gayman receives a bag of gold as

advance payment for an assignation "ith an anonymous "oman# 2ere the desirability of the gold Eassociated "ith its very anonymityF immediately implies the undesirability of the "oman "ho sends it 83ome female devil, old and damned to ugliness, ! 0nd past all hopes of courtship and address, ! Full of another devil called desire, ! 2as seen this face, this shape, this youth, ! 0nd thinks it's "orth her hire# 1t must be so8# 6f course, as this passage emphasiCes, in both cases the "omen's money stands for Gayman's se?ual "orthiness, but as such it again marks a difference, the difference in the desirability of the bodies to be e?changed# 2ence the unlike substance, gold, marks the ineDuality of the like biological substances# /he freedom and the perils, especially the perils for "omen, that this comedy of representation through difference introduces into erotic life are e?plored in the conflict bet"een Kulia and Gayman# 0nd this conflict returns us to the issue of authorial representation# Kulia, like many of 0phra Behn's heroines, confronts a familiar predicament she "ishes to have the pleasure of se?ual intercourse "ith her lover "ithout the pain of the loss of honor# 2onor seems to mean something "holly e?ternal in the playA it is not a matter of conscience since secret actions are outside its realm# Rather, to lose honor is to give a"ay control over one's public representations# 2ence, in the adultery plot, as opposed to the crisis plot, "omen's bodies are not the true stakesA representations of bodies, especially in money and language, are the focal points of conflict# Gayman's complaint against Kulia, for e?ample, is that she prefers the public admiration of the cro"d, "hich she gains through "itty language E8talking all and loud8F to the private 8adoration8 of a lover, "hich is apparently speechless# Kulia's retort, ho"ever, indicates that it is Gayman "ho "ill betray the private to public representation for the sake of his o"n reputation# 1t is Gayman "ho "ill 8describe her charms,8 86r make most filthy verses of me ! 7nder the name of Cloris, you <hilander, ! 9ho, in le"d rhymes, confess the dear appointment, ! 9hat hour, and "here, ho" silent "as the night, ! 2o" full of love your eyes, and "ishing mine#8 E9e have Gust, by the "ay, heard Gayman sing a verse about Cloris's "ishing eyes to his landlady#F /o escape being turned into someone else's language, losing the ability to control her o"n public presentation, Kulia subGects herself to a much more radical severance of implied true self from self$ representation than Gayman could have imagined# 0t once to gratify her se?ual desire and preserve her honor, she arranges to have Gayman's o"n money Ein some "ays a sign of his desire for herF misrepresented to him as payment for se?ual intercourse "ith an unkno"n "oman# /hat is, Kulia makes the anonymous advance earlier discussed# Kulia, then, is hiding behind the anonymity of the gold, relying on its nature as a universal eDuivalent for desire, universal and anonymous precisely because it doesn't resemble "hat it stands for and can thus stand for anything# But in this episode, she becomes a prisoner of the very anonymity of the representation# For, as "e've already seen, Gayman takes it as a sign of the difference bet"een the "oman's desirability and his o"n# 0pparently, moreover, this representation of her undesirability over"helms the private e?perience itself, so that "hen the couple finally couples, Gayman does not actually e?perience Kulia, but rather feels another version of his landlady# 0s he later reluctantly describes the sightless, "ordless encounter to Kulia E"hom he does not suspect of having been the "omanF, 83he "as laid in a pavilion all formed of gilded clouds "hich hung by geometry, "hither 1 "as conveyed after much ceremony, and laid in a bed "ith her, "here, "ith much ado and trembling "ith my fears, 1 forced my arms about her#8 80nd sure,8 interGects Kulia aside to the audience, 8that undeceived him#8 8But,8 continues Gayman, 8such a carcass 't"as, deliver me, so shrivelled, lean and rough, a canvas bag of "ooden ladles "ere a better bedfello"#8 8=o", though, 1 kno" that nothing is more distant than 1 from such a monster, yet this angers me,8 confides Kulia to the audience# '83life, after all to seem deformed, old, ugly#8 /he intervie" ends "ith Gayman's final misunderstanding, 81 kne" you "ould be angry "hen you heard it#8 /he e?traordinary thing about this interchange is that it does not matter "hether or not Gayman is

telling the truth about his se?ual e?perience# /he gold may have so over"helmed his senses as to make Kulia feel like its opposite a bag of "ooden ladles rather than precious coinsA and, indeed, the continuity of images bet"een this description and Gayman's earlier reactions to "omen "ho give him money tends to confirm his sincerity# /he bag of ladles reminds us of the landlady, "ho "as also a bag, but one containing some"hat more valuable table utensils 'postle spoons and caudle cups# 2o"ever, Gayman may be misrepresenting his e?perience to prevent Kulia's Gealousy# Either "ay, Kulia "as missing from that e?perience# 9hether he did not desire her at all or desired her as someone else is immaterialA "hat Kulia e?periences as she sees herself through this doubled representation of money and language is the impossibility of keeping herself to herself and truly being gratified as at once a subGect and obGect of desire# By participating in this economy of difference, in "hich her representations are not recogniCably hers, then, Kulia's problem becomes her state of une?changeability# /he drive for self$possession removes her 8true8 self from the realms of desire and gratification# Because she has not given herself a"ay, she finds that her lover has not been able to take her# 3urprisingly, ho"ever, the play goes on to overcome this difficulty not by taking refuge in like$for$like e?changes, but by remaining in the economy of difference until Kulia seems able to adGust the claims of self$possession and gratification# /he adGustment becomes possible only after Kulia has been e?plicitly converted into a commodity "orth three hundred pounds# /he process leading up to this conversion merits our scrutiny# Gayman and 3ir Cautious are gambling Gayman has "on >(( pounds and is "illing to stake it against something of 3ir Cautious's# 3ir Cautious 1 "ish 1 had anything but ready money to stake three hundred pound, a fine sumB Gayman @ou have moveables 3ir, goods, commodities# 3ir Cautious /hat's all one, 3ir# /hat's money's "orth, 3ir, but if 1 had anything that "ere "orth nothing# Gayman @ou "ould venture it# 1 thank you, 3ir# 1 "ould your lady "ere "orth nothing# 3ir Cautious 9hy so, 3ir; Gayman /hen 1 "ould set all 'gainst that nothing# 3ir Cautious begins this dialogue "ith a comical identification of everything "ith its universal eDuivalent, money# Everything he o"ns is convertable into moneyA hence, he believes that money is the real essence of everything that isn't money# 2ence, everything is really the same thing$$money# For 3ir Cautious the economy of difference collapses everything into sameness# /he only thing that is truly different, then, must be 8nothing,8 a common slang "ord for the female genitals# 6ne's "ife is this nothing because in the normal course of things she is not a commodity# 0s 3ir Cautious remarks, 89hy, "hat a lavish "horemaker's this; 9e take money to marry our "ives but very seldom part "ith 'em, and by the bargain get money8# 2er normal none?changeability for money is "hat makes a "ife different from a prostituteA it is also "hat makes her the perfect nothing to set against three hundred pounds# 9e could say, then, that Kulia is here made into a commodity only because she isn't one she becomes the principle of universal difference and as such, parado?ically, becomes e?changeable for the universal eDuivalent# /he scene provides a structural parallel for the scene of Gayman's prostitution, in "hich, as "e have seen, money also marks difference# But the seDuels of the t"o scenes are strikingly dissimilar# Gayman is once again back in Kulia's bed, but his rather than her identity is supposedly masked# 9hereas in the first encounter, Gayman "ent to bed "ith "hat he thought "as an old "oman, in the second, Kulia goes to bed "ith "hat she thinks is her old husband# But the difference bet"een these

t"o scenes in the dark as they are later recounted stems from the relative inalienability of male se?ual identity# Even in the dark, "e are led to believe, the difference of men is sensible Gayman says, 81t "as the feeble husband you enGoyed ! 1n cold imagination, and no more# ! 3hyly you turned a"ay, faintly resignedJhellipA# /ill e?cess of love betrayed the cheat#8 Gayman's body, even unseen, is not interchangeable "ith 3ir Cautious's# 7nlike Kulia's, Gayman's body "ill undo the misrepresentationA no mere idea can eradicate this palpable difference and sign of identity, the tumescent penis itself# 2ence, "hen Gayman takes 3ir Cautious's place in bed, he does not really risk "hat Kulia suffered earlier 8after all to seem deformed, old, ugly#8 Gayman's self "ill al"ays obtrude into the sphere of representation, another version of the ladle, but one that proGects from the body instead of being barely discernible "ithin it# /his inalienable masculine identity, although it seems at first Gayman's advantage, is Duickly appropriated by Kulia, "ho uses it to secure at once her o"n good reputation and complete liberty of action# 6nce again "e are given a scene in "hich the speaker's sincerity is Duestionable# 9hen Gayman's erection reveals his identity, Kulia appears to be outraged at the attempted deception 89hat, make me a base prostitute, a foul adult'ress; 6h, be gone, dear robber of my Duiet8# 9e can only see this tirade as more deceit on Kulia's part, since "e kno" she tricked the same man into bed the night before# But since her deceit "as not discovered and his "as, she is able to feign outrage and demand a separation from her husband# /he implication is, although, once again, this cannot be represented, that Kulia has found a "ay to secure her liberty and her 8honor8 by maintaining her misrepresentations# 1t is, then, precisely through her nullity, her nothingness, that Kulia achieves a ne" level of self$ possession along "ith the promise of continual se?ual e?change# But this, of course, is an inference "e make from "hat "e suspect Kulia of hiding her pleasure in Gayman's body, her delight that she no" has an e?cuse for separating from her husband, her intention to go on seeking covert pleasure# 0ll of this is on the other side of "hat "e see and hear# 1t is this shady effect, 1 "ant to conclude, that 0phra Behn is in the business of selling# 0nd it is by virtue of this commodity that she becomes such a problematic figure for later "omen "riters# For they had to overcome not only her life, her ba"diness and the author$"hore metaphor she celebrated, but also her playful challenges to the very possibility of female self$representation

You might also like

- Life in A Love: Poem Text Poem Text Themes ThemesDocument9 pagesLife in A Love: Poem Text Poem Text Themes ThemesSuhad Jameel Jabak0% (1)

- Aristophanes - Assemblywomen (Barrett)Document52 pagesAristophanes - Assemblywomen (Barrett)Docteur LarivièreNo ratings yet

- Rape of The LockDocument5 pagesRape of The LockShaimaa SuleimanNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare's RomancesDocument5 pagesShakespeare's RomancesMaria DamNo ratings yet

- The Taming of the Shrew (Annotated by Henry N. Hudson with an Introduction by Charles Harold Herford)From EverandThe Taming of the Shrew (Annotated by Henry N. Hudson with an Introduction by Charles Harold Herford)Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (1711)

- Beginning Theory StudyguideDocument29 pagesBeginning Theory StudyguideSuhad Jameel Jabak80% (5)

- Business Games Teaching EnglishDocument79 pagesBusiness Games Teaching Englishladyreveur97% (31)

- Module in Criminal Law Book 2 (Criminal Jurisprudence)Document11 pagesModule in Criminal Law Book 2 (Criminal Jurisprudence)felixreyes100% (3)

- Absurd Drama - Martin EsslinDocument10 pagesAbsurd Drama - Martin EsslinSimone MottaNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical Movere in Hamlet: Student: Alexiu Adela-Elena Major: ChineseDocument4 pagesRhetorical Movere in Hamlet: Student: Alexiu Adela-Elena Major: ChineseAdela AlexiuNo ratings yet

- Othello As Tragic HeroDocument5 pagesOthello As Tragic Heroapi-300710390100% (1)

- The Theory of the Theatre, and Other Principles of Dramatic CriticismFrom EverandThe Theory of the Theatre, and Other Principles of Dramatic CriticismNo ratings yet

- The Masks of Othello: The Search for the Identity of Othello, Iago, and Desdemona by Three Centuries of Actors and CriticsFrom EverandThe Masks of Othello: The Search for the Identity of Othello, Iago, and Desdemona by Three Centuries of Actors and CriticsNo ratings yet

- Saint Joan As A Tragegic HeroDocument8 pagesSaint Joan As A Tragegic Herovkumar_345287100% (4)

- FRYE Characterization in Shakespearian ComedyDocument8 pagesFRYE Characterization in Shakespearian Comedycecilia-mcdNo ratings yet

- The Best Short Stories of Edgar Allan Poe (Illustrated by Harry Clarke with an Introduction by Edmund Clarence Stedman)From EverandThe Best Short Stories of Edgar Allan Poe (Illustrated by Harry Clarke with an Introduction by Edmund Clarence Stedman)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (12)

- Compilation John DonneDocument27 pagesCompilation John DonneHasan KurbanNo ratings yet

- Essay LitDocument5 pagesEssay Litb.espin.sanchezNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of The Famous Poem When You Are OldDocument6 pagesAn Analysis of The Famous Poem When You Are Oldanon_919669374No ratings yet

- The WaltzDocument4 pagesThe WaltzИгорь ГромNo ratings yet

- Dfadf ShakespeareDocument12 pagesDfadf Shakespeareapi-242119616No ratings yet

- Stories and StorytellingDocument3 pagesStories and StorytellingRoy Boffey100% (2)

- Literary TermsDocument6 pagesLiterary TermsLee MeiNo ratings yet

- The Circus Animals-SummaryDocument8 pagesThe Circus Animals-SummaryJuliusNo ratings yet

- Notes On CampDocument12 pagesNotes On CampmadaandreeaNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare's Plays: TragedyDocument2 pagesShakespeare's Plays: TragedyAhsan AliNo ratings yet

- Theatre of The AbsurdDocument7 pagesTheatre of The AbsurdAnamaria OnițaNo ratings yet

- Absurd EsslinDocument14 pagesAbsurd EsslinChristopher Daniel Serna RuizNo ratings yet

- 06 - Chapter 1 PDFDocument30 pages06 - Chapter 1 PDFPIYUSH KUMARNo ratings yet

- Staging The Puppet Show in Bartholomew FairDocument20 pagesStaging The Puppet Show in Bartholomew FairRose-Marie WaltonNo ratings yet

- The Theatre of The AbsurdDocument10 pagesThe Theatre of The AbsurdMais MirelaNo ratings yet

- Irony in World DramasDocument7 pagesIrony in World DramasResearch ParkNo ratings yet

- 18th Century DramaDocument2 pages18th Century DramaPaulescu Daniela AnetaNo ratings yet

- The Tempest - Epilogue CriticismsDocument2 pagesThe Tempest - Epilogue CriticismsMiss_M9050% (4)

- The Raven - Symbolism and Unity of EffectDocument10 pagesThe Raven - Symbolism and Unity of Effectdenerys2507986No ratings yet

- The Futurist Cinema, 1916Document5 pagesThe Futurist Cinema, 1916elise_mourikNo ratings yet

- OCG Essay On Scene 6Document2 pagesOCG Essay On Scene 6Beth KingNo ratings yet

- The Theatre of The AbsurdDocument14 pagesThe Theatre of The AbsurdAyushman ShuklaNo ratings yet

- CH 02Document35 pagesCH 02towsenNo ratings yet

- Drama AssignmentDocument15 pagesDrama AssignmentLakshaySharmaNo ratings yet

- Adobe Scan 06 Sep 2021Document9 pagesAdobe Scan 06 Sep 2021gopikaNo ratings yet

- A Collection of Short FictionDocument152 pagesA Collection of Short FictiondraykidNo ratings yet

- Shakespeare and The Art of Mise en Abyme L3Document3 pagesShakespeare and The Art of Mise en Abyme L3chevallierNo ratings yet

- The Wise Fool in Shakespeares PlaysDocument91 pagesThe Wise Fool in Shakespeares PlaysIonutSilviuNo ratings yet

- Ode On A Grecian UrnDocument5 pagesOde On A Grecian UrnAslı As100% (1)

- On Waste Land Analysis All PoemDocument55 pagesOn Waste Land Analysis All PoemNalin HettiarachchiNo ratings yet

- Xxxtraducere Beckett& IonescoDocument7 pagesXxxtraducere Beckett& IonescoEugenia Maria PaşcaNo ratings yet

- Origins of Drama in The African Context FreeDocument10 pagesOrigins of Drama in The African Context FreeLuciaNo ratings yet

- Ode On A Grecian UrnDocument3 pagesOde On A Grecian UrneἈλέξανδροςNo ratings yet

- Twelfth Night Term Paper TopicsDocument7 pagesTwelfth Night Term Paper Topicsafdtwadbc100% (1)

- Theatrical Convention and Audience Response in Early Modern Drama (J Lopez)Document249 pagesTheatrical Convention and Audience Response in Early Modern Drama (J Lopez)Mike MorrisNo ratings yet

- Arms & The ManDocument76 pagesArms & The ManMaruf HossainNo ratings yet

- TheatreDocument8 pagesTheatreRazaw HamdiNo ratings yet

- Characterstics of Elizabethan DramaDocument2 pagesCharacterstics of Elizabethan DramaEsther BuhrilNo ratings yet

- Abstracts On Marcel AntonioDocument6 pagesAbstracts On Marcel AntonioMarcel AntonioNo ratings yet

- Brooke 1964 - The Characters of DramaDocument11 pagesBrooke 1964 - The Characters of DramaPatrick DanileviciNo ratings yet

- Samuel Taylor ColeridgeDocument8 pagesSamuel Taylor Coleridgeapi-300603674No ratings yet

- Course Objectives: SLO #4,5 and 8:: DE. Use Strategies For Independent Learning Apply Critical Thinking Skills ContextDocument4 pagesCourse Objectives: SLO #4,5 and 8:: DE. Use Strategies For Independent Learning Apply Critical Thinking Skills ContextSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- Formalism: Object-Centered Theory Focus Only On The Work Itself Do Not Focus On The Artist of The Observer/audienceDocument6 pagesFormalism: Object-Centered Theory Focus Only On The Work Itself Do Not Focus On The Artist of The Observer/audienceSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- Application Activity Using The PassiveDocument1 pageApplication Activity Using The PassiveSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- Bookrags Literature Study Guide: All My Sons by Arthur MillerDocument41 pagesBookrags Literature Study Guide: All My Sons by Arthur MillerSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- Gendered MediaDocument11 pagesGendered MediaSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- AlchemistDocument20 pagesAlchemistSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- Put The Verb Into The Correct FormDocument3 pagesPut The Verb Into The Correct FormSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- History of ESL Teaching MethodsDocument3 pagesHistory of ESL Teaching MethodsSuhad Jameel JabakNo ratings yet

- She Said He Said Credibility and Sexual HarassmentDocument11 pagesShe Said He Said Credibility and Sexual HarassmentNatalia AcevedoNo ratings yet

- Saqifa Bani Sa'idahDocument2 pagesSaqifa Bani Sa'idahShadabul HaqueNo ratings yet

- RSS-China MOU?Document3 pagesRSS-China MOU?cbcnnNo ratings yet

- 2012-07-26 HK Magazine - Hong Kong's Expensive Wine IndustryDocument5 pages2012-07-26 HK Magazine - Hong Kong's Expensive Wine IndustryspikescellarNo ratings yet

- Resume Project CoordinatorDocument1 pageResume Project CoordinatorRamesh KumarNo ratings yet

- AS-Live LogDocument3 pagesAS-Live LogarteadNo ratings yet

- 1.18.2024 SBFCC Create Morre Eopt Beps 2.0Document70 pages1.18.2024 SBFCC Create Morre Eopt Beps 2.0b86120298alexlinNo ratings yet

- In The Court of The City Civil Judge at Bangalore (Cch-3)Document7 pagesIn The Court of The City Civil Judge at Bangalore (Cch-3)Erika HarrisNo ratings yet

- Philokalia: Kallos "Beauty") Is "A Collection of Texts Written Between The 4th and 15th Centuries by Spiritual Masters"Document10 pagesPhilokalia: Kallos "Beauty") Is "A Collection of Texts Written Between The 4th and 15th Centuries by Spiritual Masters"estudosdoleandro sobretomismoNo ratings yet

- SEO Proposal For Pakiza - DocxDocument6 pagesSEO Proposal For Pakiza - Docx67Rampur BaghelanNo ratings yet

- AdvertisementsDocument9 pagesAdvertisementsSashi Raj100% (2)

- On Early Christian ExegesisDocument39 pagesOn Early Christian Exegesisasher786No ratings yet

- Reading IN Philippine History: Prepared By: Aiza S. Rosalita, LPT Bsba InstructorDocument100 pagesReading IN Philippine History: Prepared By: Aiza S. Rosalita, LPT Bsba InstructorRanzel SerenioNo ratings yet

- Macro PresentationDocument15 pagesMacro PresentationBeing indianNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis On Bumrungrad' Global SDocument8 pagesCase Analysis On Bumrungrad' Global SSahil AnujNo ratings yet

- SEC Primary RegistrationDocument13 pagesSEC Primary RegistrationElreen Pearl AgustinNo ratings yet

- Un/une Le/la/les Du/de La /desDocument2 pagesUn/une Le/la/les Du/de La /desleprachaunpixNo ratings yet

- English Grammar ExerciseDocument8 pagesEnglish Grammar ExerciseLeonardo Jr PinedaNo ratings yet

- Angie Ucsp Grade 12 w3Document6 pagesAngie Ucsp Grade 12 w3Princess Mejarito MahilomNo ratings yet

- DIG - Vir Jen Shipping and Marine Services Vs NLRC 1983 Case DigestDocument4 pagesDIG - Vir Jen Shipping and Marine Services Vs NLRC 1983 Case DigestKris OrenseNo ratings yet

- Assignemnt 1 - 3 MarksDocument3 pagesAssignemnt 1 - 3 MarksHafsa HayatNo ratings yet

- Biosketch Form and SampleDocument2 pagesBiosketch Form and Sampleapi-313957091No ratings yet

- Individual Assignment 1 - GMDocument10 pagesIndividual Assignment 1 - GMIdayuNo ratings yet

- Reflective ReportDocument6 pagesReflective ReportZulkifli Che HusinNo ratings yet

- Candidate List 64CCE 10-09-2018 OAPDocument115 pagesCandidate List 64CCE 10-09-2018 OAPOm PrakashNo ratings yet

- Amulya Garg DmbaDocument27 pagesAmulya Garg DmbaAsha SoodNo ratings yet

- Cherniss - The Platonism of Gregory of NyssaDocument96 pagesCherniss - The Platonism of Gregory of Nyssa123Kalimero100% (1)

- No. Branch (Mar 2022) Legal Name Organization Level 4 (1 Mar 2022) Average TE/day, 2019 Average TE/day, 2020 Average TE/day, 2021 (A)Document7 pagesNo. Branch (Mar 2022) Legal Name Organization Level 4 (1 Mar 2022) Average TE/day, 2019 Average TE/day, 2020 Average TE/day, 2021 (A)Irfan JauhariNo ratings yet

- A Historical Perspective On Light Infantry: 1ST Special Service Force, Part 10 of 12Document12 pagesA Historical Perspective On Light Infantry: 1ST Special Service Force, Part 10 of 12Bob CashnerNo ratings yet