Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Efik Obutong

Efik Obutong

Uploaded by

Merry CorvinCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Efik Obutong

Efik Obutong

Uploaded by

Merry CorvinCopyright:

Available Formats

Upload Browse DownloadStandard viewFull view OF 376 Cuban Abakua Chants Ratings: (0)|Views: 565|Likes: 5 Published by Taiwo6 See

More

tion of spoken phrases into words. For instance, in the above example( Okobio Enye nisn, awana bekura mendo/ Nnkue Itia Ororo Knde Ef Kebutn/ Oo kue ), what I had written as Ef Kebton was interpreted by Orok Edem as Efik Obutong , indicating that in Cuban usage, Cross Riverterms may be joined or resegmented, making them additionally difficult tointerpret. I generally determined the word breaks in the Cuban textsaccording to instructions by Abaku elders, who did most of the interpre-tations into Spanish. When in doubt, I referred to published Ab aku vocab-ularies. In fact, I reviewed many such vocabularies with Abaku elders. I nsome instances, I intentionally do not translate some terms fully, because todo so would articulate obscure passages designed to hide information tononinitiate s. Abaku leaders would not approve translation of these partic-ular phrases.Furth er complicating translation is the fact that Cross River kpe andgbe each seem to h ave an initiation dialect which is derived from locallanguages whose codes have be en switched so that they are unintelligibleto a noninitiate (see Miller 2000; Ru el 1969:231, 245). The fact that we canmake some sense of Abaku through kpe and Ef ik terms suggests a direc-tion for further linguistic study.In what follows, I d ocument how Abaku leaders use these chants toexpress their cultural history. I be gin by presenting a transcribed Abakuchant, followed by an English translation of the Spanish phrases and termsused by Abaku leaders to interpret them. After this , I document transla-tions into Efik or another Cross River language by Orok Ede m, JosephEdem, and Callixtus Ita, all native speakers 6 ; by Bruce Connell, an author-ity on the languages of the Cross River region; an d from published sources,mainly the Rev. Hugh Goldie s 1862 Dictionary of the Efk Language, the stan-dard work. Because these multilayered interpretations are hard to read, Iuseda graphical device to identify terms in the text that correspond to West African terms. For example: anything in Goldie or another publishedsource is pla ced in square brackets [ ], and anything identified by O. Edem, J. Edem, Ita, or Connell is placed in angle brackets < >. Where both kindsof sources identity an item, then both kinds of brackets are used. Immedi-ately under the Cuban interp retation, each bracketed expression gets itstranslation with a citation. My own comments on the interpretation, if any,follow this. As an example, I begin with the already mentioned chant. First Chant Okobio <[Enyenisn]>, awana <bekura> mendo/ <[Nnk]ue [Itia][Ororo] [Knde] [Ef Kebutn]> / Oo <[kue]>.Our African brothers, from the sacred place/ came to Havana, and inR egla founded Efk Ebutn/ we salute the kue drum. Cuban Abaku Chants 27 In Abaku:Okobio = brotherEnyenisn = Africaawana bekura mendo = sacred place where the society originated Awana Bekura Mend, or Bakura Efor (formerly Bekura) wasthe most important locality of the Efor (Cabrera 1958:79).Nnkue = HavanaItia = landO roro = center (of a river)Itia Ororo Knde = name for Regla, HavanaEf Kebutn = first Abaku groupkue = sacred drum. Line 1:Okobio <[Enyenisn]>, awana <bekura> mendo

[Enyenisn] E.-ye.n -i-so.n = child of the soil, a native, a free man;ata e. ye.n iso.n = free by bo th parents (Goldie 1964: 97). 7 Inlocal usage then, eyenison would refer specifically to Efik peo-ple (see Eyo 1986:75).<Enyenisn> enyenison = son of the soil, meaning we are ownersof the land (O. Edem, personal communicati on, 2001)<bekura> Bekura is a village east of Usaghade, adjacent to orpart of Eko ndo Titi. This is Londo (Balondo) country (Con-nell, personal communication, 2002 ). Line 2: <[Nnk]ue [Itia] [Ororo] [Knde] [Ef Kebutn]>. You cannot push that stone fart her than the Efik Obutong. This entire phrase in Efik would be <Nnkue Itia ororo kndeEfik Ebuton>, a standard Efik boast meaning We are strongerthan anyone else (O. Edem, personal communicati on, 2001).[Nnk] Nuk = to push; to push aside or away (Goldie 1964:234)[itia] I -tiat = a stone (Goldie 1964:139)[ororo] O -ru.= that (Goldie 1964:256)[knde] U -kan = s uperiority; mastery (Goldie 1964:312)[Ef Kebutn] O.b -u-to.n = Old Town, a village s ituated a short distance above Duke Town (Goldie 1964:360)<Ef Kebutn> = Obutong, a n Efik town near Duke Town (O.Edem, personal communication, 2001)It should be no ted that Orak Edem s translation, above, does not coincide with Cuban interpretati ons, which hold Nnkue and Oror to be placenames (see Cabrera 1958:73). Edem s interp retation is plausible, however, 28 African Studies Review

because southern Nigerian initiation jargons commonly use proverbs, suchas the a bove, as a form of figurative speech (see Green 1958). Line 3:Oo <[kue]> [kue] kpe = leopard (Goldie 1964:74). Hence the name of thisinstitution is literal ly leopard men. Ek -pe = the Egbo [kpe] institution as a whole, comprising allthe grad es (Goldie 1964:74)(Ortiz [1955:208] wrote: In Cuba the word kpe was converted to kue because the constant phoneme kp of the Efik language can-not be well pronounced or written in European languages . Seealso Simmons [1956:66]. In both the Cross River region andCuba, kpe/kue is als o the name of the unseen drum that roars to authorize ritual action [see Waddell 1 863: 265 66]). Within this example are many Cuban terms that translate directly in toEfik and whose meanings overlap. Even where the meanings are very dif-ferent as in the Abaku phrase Nunkue...kande the phrase would beintelligible in context by an E fik speaker. This indicates the possibilities of Abaku for gaining insight into trans-Atlantic history.The process of interpretation documented by this article began inearnest when Orok Edem equated Cuba s first Abaku group, EfkEbutn, with Obutong an Efik town that was part of Calabar in south-eastern Nigeria. Leaders of this town and their retinues were captured by British ships and transported to the Ca ribbean, an incident well docu-mented in written sources. The battle of 1767, kn own as the Massacre of Old Calabar, was the climax of a power struggle between the neighboringOld Town (a.k.a. Obutong) and Duke Town (a.k.a. New Town) over for-e ign trade (see Simmons 1956:67 68). Duke Town leaders made a secret pact with capt ains of British slave ships anchored in the Old Calabar river.These captains in turn invited Obutong leaders aboard their vessels, osten-sibly to mediate the di spute. Once on board, three brothers of the Obu-tong chief Ephraim Robin John we re held captive, and an estimated threehundred townspeople were slaughtered. One brother, released to the DukeTown leaders, was beheaded, and the other two, alo ng with several of theirretinue, were sold as slaves in the West Indies (William s 1897:535 38; Clark-son 1968 [1808]:305 10).The rivalry among Efik settlements on t

he Calabar River lasted several years (see Northrup 1978:37; Lovejoy & Richardso n 1999:346); events suchas the one described above brought a large enough number of kpe lead-ers into slavery for them to establish Abaku in Havana. Grandy KingGeo rge [Ephraim Robin John] described the loss of four of his sons goneallredy with [ captain] Jackson and I don t want any more of them caried of Cuban Abaku Chants 29 by any other vausell (Williams 1897:544). 8 Connell (personal communi-cation, 2002) points out that this is a rare documented claim of Efik actu-ally being sent to the West Indies [no doubt there were more ]. The timegap between this incident, 1767, and the assumed founding of Abaku,183 6, is nearly sixty years, which suggests that the sons of Ephraim Robin John wer e presumably not involved. In fact, the Robin John brothers weresold in Dominica, escaped, were reenslaved in Virginia, then traveled toBristol, where they becam e enmeshed in a legal battle over their status, andeventually returned to Calaba r (Paley 2002; Sparks 2002).Meanwhile, hundreds of Africans who embarked in Cala bar were trans-ported on British ships directly to Havana. For example, in 1762 the Nancy disembarked 423 at Barbados and Havana; in 1763 the Indian Queen dis-embarked 496 at Kingston and Havana; in 1785 the Quixote disembarked290 at Trinidad and Havana; in 1804 the Mary Ellen disembarked 375 inHavana. 9 There, in spite of linguistic and ethnic diversity, they would havebeen known ge nerally as Calabar. In the mid-eighteenth century, fiveCalabar cabildos (nation groups) existed in Havana (Marrero1980:158 60); generally, these groups we re known to include kpe mem-bers and acted as incubators for the emerging Abaku. T he historian JosL. Franco (1974:179) reports that during the attempted rebellion in 1812led by the free black Jos Antonio Aponte, authorities in Havana discov-ere d a document in Aponte s possession signed with an Abaku symbol.These factors raise the possibility that early models of the Abaku society were developed in the la te eighteenth century.Efik historians have known the point of departure, but not the finaldestination. Cuban Abaku documented the language and place namesbut, un til now, they had no way to corroborate this with information from African sourc es. Thus Edem s interpretation strengthens the remarkablestory of a complex secret society being recreated under conditions of slav-ery. This feat was facilitated by the proximity of kpe leaders and their inti-mate circle, all of whom were bro ught to Havana, a cosmopolitan city con-taining many Cross River people in a lar ge free black population.The mutually reinforcing present-day Efik and Abaku inte rpretationsof historical acts allows us to create a connected account of events leadingto the refounding of an African institution in the Caribbean. This contin -uous narrative which contradicts other interpretations that describe theMiddle Pa ssage as a historical discontinuity was assembled through yearsof field work and d ocument study on both sides of the Atlantic and subse-quent collaboration betwee n academic and traditional intellectuals. One of the myths of slavery in the Ame ricas is that African cultural traditions weredestroyed. The Abaku example sugges ts that the lived reality was consid-erably more complicated than that.Months af ter communicating with Orok Edem, I learned that Fernan-do Ortiz, a leading scho lar of African influence in Cuba, had nearly fifty years earlier correctly trac ed the origin of the term Efik Obutn. Ortiz 30 African Studies Review

(1955:254) wrote that the Cuban pronunciation: Ef Butn or Efique- butn ...in the pure language of the Efik should be pronounced Efik Obutn .... Obutn was in Efk the name of a great region of Calabar...andalso of its ancient capita l, today called Old Town by the English. Ortiz sprimary concern was tracing African influence on Cuban society. To my knowledge, he never worked with Africans or t raveled to Africa; he wasinterested in the Cuban nation, not a trans-Atlantic di alogue. While sever-al of Ortiz s works had been edited during the post-1958 Revol ution andread by several Abaku I met, the work in which he states the above avail-a ble only in a first edition was very difficult to obtain in Cuba and thusnot well known by Abaku. Abaku leaders had always known that thesource for their institutio n was the Calabar region, but they had never hadan opportunity to travel or to m eet Efik people. Only in contemporary,global New York City, the Secret African Ci ty (Thompson 1991) and thefirst Caribbean city (see James 1998:12), could Cuban Aba ku and West African kpe meet. Oral History and Performance-Oriented Research Methods Since African-derived traditions in the Americas depend largely on oraltransmiss ion, oral methodologies are vital to scholarship. From the early nineteenth cent ury onward, Abaku have passed manuscripts of their owntexts from elders to select ed neophytes, who have then memorized andrecited them in various performance con texts. 10 The secrecy surroundingthese texts is evidence of the society s continued control over information.I have been fortunate to work with Abaku leaders who distinguish textscontaining historical data from those with spiritual allusions. Without ac cess to at least some of these historical passages, with their richly detailedin sights into cultural transmission and transformation, we can hardly fath-om the meaning of Abaku to the West African diaspora.By recording oral testimonies, scho lars create historical documents of the memories and accounts of the people they interview. The audio record-ed document may be examined in much the same way th at a written docu-ment is examined, making oral history a type of historiography . All histor-ical research is based on documents, none of which can be taken at face value. The student must ask: Who made them, why, for what audience; what in formation did they have available to them; what was their purpose in cre-ating t hese documents?In establishing this oral history, I was greatly aided by a varia tion of an Afro-Cuban performance technique known as controversia , which is similarto forms of signifying in North America and other regions in the Africandiaspora. 11 Cubans use many terms to describe musical variants of call-and-response interact ions. Ortiz (1981:54) wrote: The congos often employ,among other responsorial cha nts, those in Cuba called de puya , makagua or Cuban Abaku Chants 31 managua , in which two alternating soloists chant, sustaining a controversy.Chants of cou nterpoint, of challenge, [are offered by] payadores [singers who perform improvised musical dialogues]. At times the chorus meddles

with the phrases of the chanting gallos [soloists] to stimulate the perfor-mance. Between one ceremony and another in thei r rites, wrote Ortiz(1981:75), the Abaku entertain themselves publicly to the rhyth ms of their orchestra, chanting inas or bfumas , which they also call decimas , or verses of challenge, aphorism, or history. In Efik, the literal meaning of inua is mouth; figuratively it can mean boastful and is related to the word eneminua , which is a flatterer (Aye 1991:56).In Abaku ritual performance, lead singers co mpete with each other todemonstrate musical skill as well as knowledge of histor ical texts. When Ilearned a passage and its translation, I would take it to vari ous Abaku lead-ers. 12 I found that in reciting their own versions, some sages would offerinsights into the material by extending the text or by giving more complexinterpretations, wh ile also demonstrating mastery of the form. 13 Abaku Chant Their History After the kpe Abaku encounter, I visited an Abaku leader in Havana.Interested that W est African kpe had interpreted Cuban texts, and in thespirit of controversia , he gave me the following chant containing what hebelieved to be the names of E fik founders of the society in Cuba. Thischant, one of hundreds in contemporary practice commemorating thetransmission of West and Central West African traditio ns, is performedbefore initiation ceremonies in remembrance of Efik leaders cons ideredfounders of the group Efik Ebutn in Cuba. 14 Second Chant Line 1: <kue [asanga] abi [ep]> np.kue came to the land of the whites , or kpe that walks around in the land of the ghosts, ( Walking is used in a boastful context [O. Edem, personalcommunication, 2001]), or kpe walks in the village of ghosts. [asanga] sna = walking (in Ibibio) (Essien 1990:147)[asanga] I -san = a walk; a jour ney; a trip; a voyage (Goldie1964:135) 32 African Studies Review Activity (6) FiltersAdd to collectionReviewAdd noteLikeEmbed 1 hundred reads obatallo liked this ndokibueno liked this omidiero liked this Jose Yemaya Alvarez liked this eoghan_ballard liked this More From This User Nsala TAIWO6

73131728-prendas TAIWO6 constitutionbooklet.pdf TAIWO6 Funcion de oriate.docx TAIWO6 Osain Dara Dara Madao TAIWO6 Orisha TAIWO6 Download and print this document Read and print without ads Download to keep your version Edit, email or read offline Choose a format: .PDF.TXT Download Download and print this document Read and print without ads Download to keep your version Edit, email or read offline Choose a format: .PDF.TXT Download

About Browse Books About Scribd Team Blog Join our team! Contact Us Subscriptions Subscribe today Your subscription Gift cards Advertise with us Get started AdChoices Support Help FAQ Press Purchase Help Partners Publishers Developers / API Legal Terms Privacy Copyright Get Scribd Mobile Scribd on Appstore Scribd on Google Play Mobile Site

Copyright 2014 Scribd Inc.Language:English

You might also like

- Black Widow (David Hayter)Document122 pagesBlack Widow (David Hayter)Louise Lee Mei80% (5)

- Kikongo English DICTIONARY 2Document340 pagesKikongo English DICTIONARY 2Roberto Rosales Gonzalez80% (5)

- Ibibio LanguageDocument3 pagesIbibio LanguageTony AkpanNo ratings yet

- Juju JusticeDocument83 pagesJuju JusticedavidmccririckNo ratings yet

- An African American Religion Called WintiDocument8 pagesAn African American Religion Called WintiMerry CorvinNo ratings yet

- Memorials of Mrs Sutherland Missionary - Agnes Waddell (1883)Document185 pagesMemorials of Mrs Sutherland Missionary - Agnes Waddell (1883)Philip Nosa-AdamNo ratings yet

- Souvenir Programme of The 5th Anniversary of Henshaw VI (Obong of Calabar)Document22 pagesSouvenir Programme of The 5th Anniversary of Henshaw VI (Obong of Calabar)Philip Nosa-Adam0% (1)

- Programme of The Memorial Service of HRH Edidem Bassey Eyo Ephraim Adam III - Late Obong of Calabar and Paramount Ruler of The EfiksDocument20 pagesProgramme of The Memorial Service of HRH Edidem Bassey Eyo Ephraim Adam III - Late Obong of Calabar and Paramount Ruler of The EfiksPhilip Nosa-Adam100% (1)

- Religious Interaction in Igboland - A Case Study of Christianity and Traditional Culture in Orumba (1896-1976) PDFDocument225 pagesReligious Interaction in Igboland - A Case Study of Christianity and Traditional Culture in Orumba (1896-1976) PDFsamuelNo ratings yet

- Oyo ContemporaneoDocument81 pagesOyo ContemporaneoFilipe OlivieriNo ratings yet

- Hebrew Igbo-LinguisticDocument21 pagesHebrew Igbo-Linguisticdiego_guimarães_64100% (2)

- Swedish Ventures in Cameroon, 1883-1923: Trade and Travel, People and PoliticsFrom EverandSwedish Ventures in Cameroon, 1883-1923: Trade and Travel, People and PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Lanny Bell, Luxor Temple and The Cult of The Royal KaDocument44 pagesLanny Bell, Luxor Temple and The Cult of The Royal KaMerry Corvin100% (1)

- Ife, Cradle of the Yoruba A Handbook on the History of the Origin of the YorubasFrom EverandIfe, Cradle of the Yoruba A Handbook on the History of the Origin of the YorubasNo ratings yet

- King Eyo Honesty IIDocument101 pagesKing Eyo Honesty IIPrince Ekanem100% (1)

- Innovation: Schlumberger CareersDocument2 pagesInnovation: Schlumberger CareersHiago SorianoNo ratings yet

- Traditional: Music Chibf Inyang Nta HenshawDocument91 pagesTraditional: Music Chibf Inyang Nta HenshawPhilip Nosa-Adam100% (1)

- Implications For The Future GenerationDocument11 pagesImplications For The Future GenerationTony AkpanNo ratings yet

- Historical Development of Muslim Education in Yoruba Land, Southwest Nigeria.Document9 pagesHistorical Development of Muslim Education in Yoruba Land, Southwest Nigeria.Tunde OgunbadoNo ratings yet

- Mantle - 2002 - The Roles of Children in Roman ReligionDocument22 pagesMantle - 2002 - The Roles of Children in Roman ReligionphilodemusNo ratings yet

- Nze Chukwuka E. Nwafor - The Ecotheology of AhobinaguDocument7 pagesNze Chukwuka E. Nwafor - The Ecotheology of Ahobinagusector4bkNo ratings yet

- The Tone System of Ibibio: Eno-Abasi Urua University of Uyo, Nigeria/Universität Bielefeld, GermanyDocument17 pagesThe Tone System of Ibibio: Eno-Abasi Urua University of Uyo, Nigeria/Universität Bielefeld, GermanyAniekanNo ratings yet

- English Ibo Dictionary HeeboDocument7 pagesEnglish Ibo Dictionary HeeboDoor Of ElNo ratings yet

- The History of King Jaja of Opobo - NaijaBiographyDocument3 pagesThe History of King Jaja of Opobo - NaijaBiographyBamstep OmotayoNo ratings yet

- Becoming Mozambique. Diaspora and Identity in MauritiusDocument19 pagesBecoming Mozambique. Diaspora and Identity in Mauritiusnuila100% (1)

- Aksum EmpireDocument16 pagesAksum Empireapi-388925021No ratings yet

- Ilé-Ifè: : The Place Where The Day DawnsDocument41 pagesIlé-Ifè: : The Place Where The Day DawnsAlexNo ratings yet

- History of Calabar Aoh Updated VersionDocument4 pagesHistory of Calabar Aoh Updated VersionDane_Gilbert_3590No ratings yet

- Introducing Etubom Boco Eneyo Cobham - The Obong-Elect of Calabar and Paramount Ruler-Elect of The EfiksDocument12 pagesIntroducing Etubom Boco Eneyo Cobham - The Obong-Elect of Calabar and Paramount Ruler-Elect of The EfiksPhilip Nosa-Adam100% (1)

- Ibibio DictionaryDocument132 pagesIbibio Dictionaryandyeffiong50% (2)

- Souvenir Programme of The Coronation of Obong Archibong V (April 1954) (Nigerian Field 19)Document12 pagesSouvenir Programme of The Coronation of Obong Archibong V (April 1954) (Nigerian Field 19)Philip Nosa-AdamNo ratings yet

- (Rida) Culture of IgboDocument7 pages(Rida) Culture of IgboUme lailaNo ratings yet

- Self DeterminationDocument13 pagesSelf DeterminationTWWNo ratings yet

- Historical/Significant Sites in Azumini, Ndoki: UminiDocument16 pagesHistorical/Significant Sites in Azumini, Ndoki: UminiBright SamuelNo ratings yet

- THORNTON John Origin Traditions and History in Central AfricaDocument9 pagesTHORNTON John Origin Traditions and History in Central AfricaAndrea MendesNo ratings yet

- BIAFRAThe Slave Trade and Culture PDFDocument304 pagesBIAFRAThe Slave Trade and Culture PDFPerla Valero100% (3)

- Social and Cultural Changes in Efik Society (1850-1930) - Gloria Ekpo Edem (June 1985)Document173 pagesSocial and Cultural Changes in Efik Society (1850-1930) - Gloria Ekpo Edem (June 1985)Philip Nosa-Adam75% (4)

- IgboDocument56 pagesIgboapi-204785694No ratings yet

- The Implications of Rapid Development On Igbo Sense of CommunalismDocument134 pagesThe Implications of Rapid Development On Igbo Sense of CommunalismJamal FadeNo ratings yet

- Sovereignty LTD - Sir George Goldie and The Rise of The Royal Niger CompanyDocument65 pagesSovereignty LTD - Sir George Goldie and The Rise of The Royal Niger CompanyTae From Da ANo ratings yet

- Phonology of The OrmaDocument39 pagesPhonology of The OrmasemabayNo ratings yet

- Origin and Meaning of BornoDocument20 pagesOrigin and Meaning of BornoBabagana AbubakarNo ratings yet

- Akan TwiDocument272 pagesAkan TwidaowonimdeeNo ratings yet

- IbibioDocument14 pagesIbibioTony AkpanNo ratings yet

- Ikorodu HistoryDocument4 pagesIkorodu HistoryBashorun MosesNo ratings yet

- Eyo Okon Akak, Who Owns Bakassi Anie Enyene Bakassi A Critique of 1885 1913 Anglo German Treaties and 1975 Gowon Ahidjo Accord in Nigeria Cameroon Boundary Dispute Calabar - The Author - 1999Document108 pagesEyo Okon Akak, Who Owns Bakassi Anie Enyene Bakassi A Critique of 1885 1913 Anglo German Treaties and 1975 Gowon Ahidjo Accord in Nigeria Cameroon Boundary Dispute Calabar - The Author - 1999OSGuineaNo ratings yet

- Travels, Researches, and Missionary Labors, During An Eighteen Years' Residence in Eastern AfricaDocument520 pagesTravels, Researches, and Missionary Labors, During An Eighteen Years' Residence in Eastern AfricaHellen KimanthiNo ratings yet

- CamerunDocument25 pagesCamerunMarco ReyesNo ratings yet

- Traditional African Taboos and General Communal WelfareDocument4 pagesTraditional African Taboos and General Communal WelfareStephen Duasua Yankey67% (3)

- Appraising The Osu Caste System in Igbo LandDocument67 pagesAppraising The Osu Caste System in Igbo LandOsu Phenomenon Files100% (1)

- Chukwuma Azuonye - The Nwagu Aneke Igbo ScriptDocument18 pagesChukwuma Azuonye - The Nwagu Aneke Igbo Scriptsector4bk100% (2)

- Yoruba and Benin Kingdom - Ile Ife The Final Resting Place of HistoryDocument5 pagesYoruba and Benin Kingdom - Ile Ife The Final Resting Place of HistoryugwakaluNo ratings yet

- UCLA James S. Coleman African Studies CenterDocument13 pagesUCLA James S. Coleman African Studies CenterstultiferanavisNo ratings yet

- Suicide in Yoruba OntologyDocument6 pagesSuicide in Yoruba OntologyEdu Gehrke100% (1)

- Ilaje and ArogboDocument9 pagesIlaje and Arogbosamuel100% (1)

- Okrika DictionaryDocument137 pagesOkrika DictionaryOba Fred AjubolakaNo ratings yet

- A Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper, from American SlaveryFrom EverandA Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper, from American SlaveryNo ratings yet

- Abraha Encyclopaedia IslamicaDocument8 pagesAbraha Encyclopaedia IslamicaygurseyNo ratings yet

- AR Armenian Language LessonsDocument18 pagesAR Armenian Language LessonsMerry CorvinNo ratings yet

- Angola HistoryDocument263 pagesAngola HistoryMerry CorvinNo ratings yet

- A History of Greek ReligionDocument320 pagesA History of Greek ReligionIoana Mihai Cristian100% (4)

- Reynhout 2006 - Social Stories For Children With DisabilitiesDocument26 pagesReynhout 2006 - Social Stories For Children With DisabilitiesMerry CorvinNo ratings yet

- List of Hieroglyphs From Gardiner Egyptian GrammarDocument108 pagesList of Hieroglyphs From Gardiner Egyptian GrammarMerry CorvinNo ratings yet

- EAS - QuestionnaireDocument58 pagesEAS - QuestionnaireMerry CorvinNo ratings yet

- Aguaruna Jivaro MagicDocument22 pagesAguaruna Jivaro MagicMerry CorvinNo ratings yet

- Odinani The Igbo Religion EbookDocument176 pagesOdinani The Igbo Religion EbookAbdulkarim DarwishNo ratings yet

- Arara LanguageDocument138 pagesArara LanguageMerry CorvinNo ratings yet

- Initiation Story by PlathDocument10 pagesInitiation Story by PlathMerry CorvinNo ratings yet

- Women in YorubaDocument15 pagesWomen in YorubaMerry CorvinNo ratings yet

- Bourne ImperativeDocument927 pagesBourne ImperativeMerry Corvin100% (3)

- Luluwa SpiritualityDocument24 pagesLuluwa SpiritualityMerry CorvinNo ratings yet

- Arara LanguageDocument138 pagesArara LanguageMerry CorvinNo ratings yet

- 5 Forces DID ShamaiDocument133 pages5 Forces DID ShamaiMerry CorvinNo ratings yet

- List of Hieroglyphs From Gardiner Egyptian GrammarDocument108 pagesList of Hieroglyphs From Gardiner Egyptian GrammarMerry CorvinNo ratings yet

- Exercises On ParallelismDocument1 pageExercises On ParallelismJennifer Garcia EreseNo ratings yet

- Interpreting HomesDocument4 pagesInterpreting Homesindrani royNo ratings yet

- 4rth English 2019Document4 pages4rth English 2019Jhuve LhynnNo ratings yet

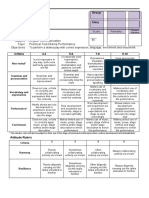

- Subject: English Communication Topic: Practical Test Drama Performance ObjectivesDocument1 pageSubject: English Communication Topic: Practical Test Drama Performance Objectivesanissa paneNo ratings yet

- Adjective + Preposition ListDocument4 pagesAdjective + Preposition ListRadu IonelNo ratings yet

- Evdg TC in l1 U11 l01 LessonDocument11 pagesEvdg TC in l1 U11 l01 LessonJuan camilo FlorezNo ratings yet

- Ipsit Pradhan PDFDocument2 pagesIpsit Pradhan PDFSOUMYA RANJAN PRADHANNo ratings yet

- Semitic Languages: From Wikipedia, The Free EncyclopediaDocument14 pagesSemitic Languages: From Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopediathitijv6048No ratings yet

- Quarter 1 Week 1 English 4Document52 pagesQuarter 1 Week 1 English 4San Vicente ESNo ratings yet

- Latin MaximDocument2 pagesLatin MaximKimberly Leian Estilong ÜNo ratings yet

- Language Assessment: Education in 2500 Words LengthDocument2 pagesLanguage Assessment: Education in 2500 Words Lengthwayan suastikaNo ratings yet

- PersonalityDocument6 pagesPersonalitythuyNo ratings yet

- EAP Foundation YouTube 25 CollocationsDocument8 pagesEAP Foundation YouTube 25 CollocationsRovie SaladoNo ratings yet

- Structures in Assembly Language Programs: What Is A Record (Structure) ?Document11 pagesStructures in Assembly Language Programs: What Is A Record (Structure) ?PRADEEP KUMARNo ratings yet

- Schema The Present Simple Vs The Present ContinuousDocument5 pagesSchema The Present Simple Vs The Present ContinuousirinachircevNo ratings yet

- The Spiritual Self - Understanding The Self Hand OutDocument20 pagesThe Spiritual Self - Understanding The Self Hand OutKyli AngNo ratings yet

- 5teaching An ESL EFL Writing CourseDocument4 pages5teaching An ESL EFL Writing Courseronanjosephd100% (3)

- AnswersDocument8 pagesAnswersVikram Kaushal0% (1)

- Irregular VerbsDocument2 pagesIrregular VerbsmnavherNo ratings yet

- The Teacher-Student Communication Pattern: A Need To Follow?Document7 pagesThe Teacher-Student Communication Pattern: A Need To Follow?Alexandra RenteaNo ratings yet

- Lecture NotesDocument112 pagesLecture NotesPrithviraj ChouhanNo ratings yet

- Wish Sentence ExercisesDocument5 pagesWish Sentence Exerciseshuyen nguyenNo ratings yet

- - نموذج استرشادي محادثة واستماع الفرقة الرابعة تعليم أساسي-د. وجدان خليفةDocument4 pages- نموذج استرشادي محادثة واستماع الفرقة الرابعة تعليم أساسي-د. وجدان خليفةAhmed AmerNo ratings yet

- Soal Bahasa Inggris Dari Buki Erlangga Forward An EnglishDocument7 pagesSoal Bahasa Inggris Dari Buki Erlangga Forward An EnglishUlfa D'emilyNo ratings yet

- CSE452P Handout S.viji ViisemDocument3 pagesCSE452P Handout S.viji ViisemAkshay AnandNo ratings yet

- Installation of Hot RunnerDocument67 pagesInstallation of Hot RunnerRafi DeenNo ratings yet

- AkashaDocument106 pagesAkashacrysty cristy100% (4)

- A Creative Approach To Teaching Grammar - The What, Why and How of Teaching Grammar in Context (Peter Burrows) P 45-56Document13 pagesA Creative Approach To Teaching Grammar - The What, Why and How of Teaching Grammar in Context (Peter Burrows) P 45-56KarenNo ratings yet

- Quarter 1 Module 3 - Use of Modal VerbsDocument38 pagesQuarter 1 Module 3 - Use of Modal VerbsKeziah Lapoja100% (1)

- Artifact 1Document9 pagesArtifact 1api-284066194No ratings yet