Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Art:10.1007/s10796 012 9392 7

Art:10.1007/s10796 012 9392 7

Uploaded by

Anthony AdamsOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Art:10.1007/s10796 012 9392 7

Art:10.1007/s10796 012 9392 7

Uploaded by

Anthony AdamsCopyright:

Available Formats

Inf Syst Front DOI 10.

1007/s10796-012-9392-7

Antecedents of cognitive trust and affective distrust and their mediating roles in building customer loyalty

Jung Lee & Jae-Nam Lee & Bernard C. Y. Tan

# Springer Science+Business Media New York 2012

Abstract The present research investigates how trust and distrust differently mediate in customer perceptions of various web features in the process of building customer loyalty. Assuming trust and distrust are different in their psychological aspects, we propose that trust is a cognitively active construct, whereas distrust is an affectively active construct. To support this proposal, we select six antecedents of trust and distrust and hypothesize their different relationships as follows: 1) Antecedents with capability-based elements, such as site convenience and content relevance, are associated with trust; 2) Antecedents with relationship-affecting elements, such as customer involvement and web fraud, are associated with distrust; 3) Antecedents with both elements, such as content truthfulness and customer responsiveness, are associated with both trust and distrust. A survey is conducted on 279 online shopping mall users in Korea, and the result shows that most of the foregoing hypotheses are supported. The finding suggests: 1) Trust emerges when customers expect positive result with confidence, thereby implying that it is cognitively activated;

2) Distrust emerges when customers suspect that the seller has a vicious motivation, thereby implying that it is affectively activated. From these premises, the present study contributes to the literature by showing how trust and distrust are different, and why they should be managed differently to establish customer loyalty. Keywords Trust . Distrust . Cognition . Affect . Customer loyalty

1 Introduction The importance of trust in online businesses has long been discussed in voluminous research. Trust is an expectation that the other party will not opportunistically behave by taking advantage of the situation (Gefen et al. 2003b). Trust reduces business transaction complexity (Luhmann 1979), facilitates transactions among business parties (Moorman et al. 1993), and accelerates economic exchanges, which all lead to high scales of sales and profit (Barney and Hansen 1994). Trust also has a positive impact on various essential business factors, such as familiarity (Gefen et al. 2003a), subjective norm (Awad and Ragowsky 2008), and privacy (Kim 2008). Therefore, trust is certainly an important element, especially in an online environment (Ridings et al. 2002). In recent years, the presence of distrust in online businesses has attracted the attention of researchers due to its destructive impact on the success of businesses (McKnight et al. 2002). Simply put, distrust is a negative feeling on the conduct of another person (Lewicki et al. 1998). It is an emotional repulsion between people and can also be a fear that one party would not care about or might hurt the other (Grovier 1994). Distrust suppresses economic transactions between parties (Bigley and Pearce 1998). It blocks further

J. Lee Bang College of Business, KIMEP University, 4 Abay Avenue, Almaty 050100, Kazakhstan e-mail: junglee@kimep.kz J.-N. Lee (*) Korea University Business School, Anam-Dong Seongbuk-Gu, Seoul 136-701, Korea e-mail: isjnlee@korea.ac.kr B. C. Y. Tan Department of Information Systems, National University of Singapore, 13 computing Drive, Singapore, Singapore 117417 e-mail: btan@comp.nus.edu.sg

Inf Syst Front

business exchanges, especially in online businesses where transactions are not interpersonal. Understanding trust and distrust, such as how they emerge and diminish and how they are related with each other, is considered a high priority by researchers and practitioners because of their crucial effect on businesses (Pavlou and Gefen 2004; Lee and Choi 2011). The antecedents, mediators, and consequences of trust and distrust have been discussed in various contexts and perspectives (Dimoka 2010), whose aim is to guide organizations on how to enhance trust, avoid distrust, and outperform their competitors (Cho 2006). However, despite a significant body of research on trust and distrust (Komiak and Benbasat 2008), how the two can be distinguished from each other has not been fully discussed. For example, in the past, distrust has been considered as simply the opposite of trust (Lewicki et al. 1998). At present, however, trust and distrust are accepted as not necessarily opposite concepts (McKnight and Choudhury 2006). They may independently emerge from the same person (Lewicki et al. 1998) and can be manifested in different mechanisms (Cho 2006). The concept of distrust, possibly as a distinct entity from trust, needs to be investigated for its critical but opposite impact compared with trust. When two factors with opposite effects exist, such as trust and distrust, their dynamics must be identified to avoid misunderstanding between the cause and the effect. Without a clear understanding of the roles of trust and distrust, attributing trust or distrust to the success of a business is difficult. This particular issue on the formation of trust and distrust has been highlighted in recent research (Dimoka 2010; Komiak and Benbasat 2008). This paper aims to identify the characteristics of trust and distrust, especially their psychological aspects. It proposes that trust and distrust are different in psychological status. Therefore, people who trust and people who distrust will respond differently to various external stimuli in online businesses. Through a testing of the associations between certain stimuli and trust and distrust, trust and distrust are anticipated to be differently positioned in the cognitive and affective dimensions and hence elicit different responses to external factors and different mediations of customer loyalty. The study is organized as follows. First, the cognitive affective dimensions of the human mindset are reviewed. A research model of trust and distrust in an online business context is then proposed. Various antecedents with different characteristics are selected to highlight the psychological differences between trust and distrust. Large survey data from Korean Internet shopping mall users are collected and analyzed using structural equation modeling to validate the hypotheses. Finally, the results of the analysis are interpreted, and the theoretical contribution and practical implications of the study are discussed.

2 Theoretical background 2.1 Cognitive and affective dimensions of the human mindset The psychological foundations of human beings have been extensively discussed in various studies (Fredrickson 2001; Russell 2003) because these foundations convincingly explain why individuals behave the way they do in certain situations. These foundations also provide a theoretical lens for people to understand better how they think and act, which is generally difficult to observe from the outside. A number of researchers, including psychologists, have investigated the brain activities of humans and have developed strong foundations as reflected in various theories and practices (Fredrickson 2001). In the development of their studies, researchers used various ideas and advanced tools, such as f-MRI, which were of great help (Dimoka 2010). The use of cognition and affect as two important, exhaustive, but highly distinguishable psychological units that mediate consumer perception on behavior has been repeatedly practiced in the literature (Homburg et al. 2007). According to the cognitiveaffective systems theory of personality, individuals differ on how they categorize and encode situational stimuli and on how these encodings activate such stimuli through the complicated mediation of cognition and affect on human behavior (Mischel and Shoda 1995). In addition, McAllister (1995) and Chua et al. (2008) investigate the configuration of the cognitive and affective dimensions of trust as important business factors with distinguishable effects. The cognitive dimension of the human mind captures how people judge and assess an object based on facts and evidence (Chua et al. 2008). This dimension connotes the straightforward and conscious process of being aware of an event. Cognition is a knowledge-based, immediate understanding of exogenous stimuli, such as a partner s capability and potential (McAllister 1995). It can also subsequently form beliefs or expectations based on reason and rationale, such that it works as a base for an individuals further behavior. The cognitive aspect of an individual emphasizes the perception based on reason and evidence. Chua et al. (2008) calls it as referring to [the] head. The affective dimension captures how people feel about a subject. Affect is a state of mind that arises from ones own emotion and a sense of others feeling and motives (Chua et al 2008). It is an emotional bond between parties which does not necessarily result from reasoning and understanding but from feeling and sense (Morrow et al. 2004). Unlike cognition, however, affect is divided into two types, namely, positive affectivity such as happiness and pride (Fredrickson 2001), and negative affectivity such as worry and anger, which need to be discussed separately

Inf Syst Front

because of their different functions ( Watson and Clark 1984). Chua et al. (2008) calls affect as referring to [the] heart. Regarding the relationship between cognition and affect, whether cognitive activity is a necessary pre-condition of emotion has long been an issue of discussion. In some studies, the causal relationship between cognition and affectthat cognition influences affecthas been proposed and exercised (Chang and Chen 2009; McAllister 1995). These studies argue that the cognition unit (i.e., expectation and beliefs) should be formed first based on encoded information in order to build affect. The expectations and beliefs then shape affective responses with psychological reactions. Based on this view, cognition comes before affect. However, cognition and affect do not necessarily have causal relations; rather, they are independent units. Zajonc (1980) has argued that affect is precognitive in nature as it occurs without any extensive perceptual and cognitive processes. In addition, Hoch and Loewenstein (1991) propose that feelings of desire that consumers often experience in shopping situations may occur with little or no cognition. Berkowitz (1993) proposes that an experiential system, which is affective in nature, and a rational system, which is cognitive in nature, tend to operate in parallel in any given task. All these studies relax the causality between cognition and affect, but they also admit that affective reactions can happen automatically without active higher-order cognitive processes.

trust and distrust in online business to understand the behavior of online consumers (McKnight et al. 2002; Pavlou and Gefen 2004). Further, as antecedents of trust and distrust, site convenience, content relevance, content truthfulness, customer responsiveness, customer involvement and web fraud are selected. The selection is made among the key factors in online business (Dai et al. 2008; Tam and Ho 2006) in a way to highlight the difference between trust and distrust. Trust and distrust are then set as cognitively- and affectively- activated mediators, respectively. Finally, customer loyalty is selected as a dependent variable for its significance in online business (Srinivasan et al. 2002). In the following sections, the variables and their relations will be described in detail. 3.1 Business value: Customer loyalty to the website Loyalty refers to the overall attachment and deep commitment to a product, service, brand, or organization of a buyer (Oliver 1999). Loyal customers not only spend more than usual customers, but they also act as enthusiastic advocates for the business (Harris and Goode 2004). Therefore, loyal customers are considered as the most important profit source of online businesses (Flavin et al. 2006). In the literature, many sources of customer loyalty have been identified. For example, factors such as customer satisfaction (Chang and Chen 2009) and trust (Aydin and zer 2005) are found to be the important cursors of customer loyalty. Functional factors, such as convenience (Srinivasan et al. 2002) and website quality (Chang and Chen 2009), are also found to be the antecedents of loyalty. To form a definition, a group of researchers have attempted to integrate the behavioral aspect of loyalty with the attitudinal aspect. For example, Assael (1992) and Srinivasan et al. (2002) view loyalty as a favorable attitude toward the brand (product, seller) resulting in consistent purchase over time.

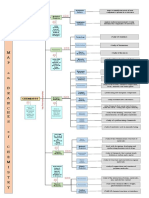

3 Research model and hypotheses A research model of trust-distrust in online business context is proposed (Fig. 1). Electronic commerce has now become one of the largest business sectors (Nielson report 2008) and numerous studies have attempted to identify the roles of

Fig. 1 Research model

Inf Syst Front

Keller (1993) defines it as favorable attitude manifested by repeated purchasing. However, when researchers empirically validate customer loyalty, behavioral aspects have been the critical indicators of loyalty affecting the feasibility of measurement. In the present study, the referent of customer loyalty is the website and not the seller or product. This is because the long-term relationships of most online shopping mall users are built based on the website and not on the specific product or seller. For example, Amazon.com users visit and purchase from Amazon.com because they have faith in the website. Amazon.com users may change the product they purchase or the sellers from which they buy, but they hardly change the website from which they purchase. Therefore, the current study views that loyalty is built toward the website and defines it as the overall attachment to a certain website with favorable attitude manifested by repeated purchasing. 3.2 Mediators: Cognitive trust and affective distrust To conceptualize trust and distrust, this study investigates the psychological aspects of both factors and proposes that trust is a cognitively activated construct, whereas distrust is affectively activated. Such difference can be argued based on their roles that trust encourages customers to buy the product, whereas distrust restrains customers from buying, hence making them passive in the business. In online businesses, trust is a factor that makes customers actively participate. It changes customer behavior from not buying to buying. Customers, on the other hand, become active when expecting positive results. Customers think, assess, and judge the situation of a business, and if the desired outcome is anticipated, customers build trust and become active. In other words, unless an evident reason can be based on rationales, customers are usually passive in the business and do not purchase products. The tendency of most customers is to make business decisions based on reasoning and evidence before they decide to enter transactions with their partners. This process is cognitive in nature. In contrast, distrust is a factor that inactivates customers. It blocks, inhibits, and restrains business transactions and changes customers from being active to passive or keeps them passive. Unlike trust, it is not only a negative anticipation of the result but can also be in various forms including just a feeling of insecurity, which makes customers passive. Most customers are risk aversive (Mas-Colell et al. 1995). Hence, although the transaction has no evident reason to result in damage, customers often become passive and decide not to buy. Based on the idea that trust is a cognitively activated construct and distrust is an affectively activated construct,

the details of the psychological statuses of trust and distrust are explained in the following sections. 3.2.1 Cognitively-activated trust In online businesses, trust refers to the belief of customers that the seller will transact in a manner consistent with the customers expectations (Pavlou and Gefen 2004). Such expectation can be formed based on the sellers competency and credibility (Dimoka 2010), which conceptually include various capabilities such as professionalism and punctuality (McKnight et al. 2002). Trust is driven by knowledge on the trustee and sensitive to the calculated risks and rewards (Johnson and Grayson 2005). Hence, it often reflects the functional competency and predictability of the trustee (Rempel et al. 1985). Dimoka (2010) also recently stated that trust is associated with brain areas linked to anticipating rewards, predicting the behavior of others, and calculating uncertainty. These characteristics indicate that building trust is a cognitively activated situation. Forming trust relies on rational evaluation and available knowledge and is based on good reasons (Jeffries and Reed 2000). Trust influences customers to initiate and continue business with their partners based on the knowledge he acquires about the trustee, reasoning, and judgment and not on their feelings and hunches. Various studies on trust also stated that trust is initiated by cognition and not affection (McAllister 1995). Cognitively initiated trust may lead, but not necessarily, to affectively initiated trust. Trust has been considered critical in establishing longterm business relationships (McKnight et al. 2002). Once trust between parties is formed, the relationship between parties can last longer by overcoming uncertainties and reducing perceived risks (Moorman et al. 1993). Naturally, trust can be argued to strengthen customer loyalty, as many previous studies have indicated (Harris and Goode 2004; Sirdeshmukh and Singh 2002). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed: H1: Trust is positively associated with customer loyalty in online businesses. 3.2.2 Affectively-activated distrust In literature, distrust is defined as a strong negative feeling regarding the conduct of another person (Lewicki et al. 1998). It is the concern that the other person does not care about ones welfare and thus may act in a harmful manner (Grovier 1994). More intuitively, distrust is a frantic, fearful, frustrated, and vengeful feeling (McKnight and Choudhury 2006). These negative characteristics of distrust suppress transactions and result in business failures once it emerges.

Inf Syst Front

Distrust is an affectively activated construct that generates a repulsive force between two parties. To emerge, an affectively activated construct does not have to go through higher order cognitive processes (Zajonc 1980) because the feeling often arises with little or no cognition (Hoch and Loewenstein 1991). For example, distrust can emerge only when the other person is suspected of being capable of doing harmful things (Sitkin and Roth 1993). With or without strong cognitive processes, distrust, which is an affectively activated notion, can arise. Distrust affects the behavior of an individual because it is an affectively strong notion. Affection is one of the most important psychological statuses that determine the subsequent action (Mischel and Shoda 1995). In this case, distrust is a construct with a negative impression. Therefore, it also has a negative impact on customer behavior. More intuitively, when customers suspect the competency and intention of sellers, their fears and worries will eventually decrease their loyalty to the sellers. Therefore, the following hypothesis is established: H2: Distrust is negatively associated with customer loyalty in online businesses. 3.3 Antecedes of trust: Capability-based factors Trust is formed when an individual can have positive expectations on the result of the transaction. It emerges when a partner appears to have sufficient competence to complete the tasks on time, as promised, and has credibility such that an individual does not have to worry about the future. Trust is strongly determined by the capabilities of a partner. Numerous studies have identified the partner s specific capabilities, such as know-how and knowledge, as the main foundations of the trust (McKnight et al. 2002). 3.3.1 Site convenience The concept of convenience has been practiced in various business contexts for a long time (Berry et al. 2002; Seiders et al. 2000). However, one generic feature of convenience is that it saves the time and effort of customers. While efficiency, which also involves a reduction in time and costs of the business, considers the organization as referent, convenience involves a reduction in the time and effort of individuals, not of the organization, and considers the customer as the referent. In online business literature, convenience has been especially important because it is one of the powerful drivers that lead consumers from offline to online purchases. Many people started to do online shopping because of the convenience involved (Bhatnagar et al. 2000). Online shopping mall users face various situations, and each time, the feature

of convenience is of different levels whenever they access, search, and pay, among others. Accordingly, numerous ecommerce studies have been conducted on convenience and have identified the sub-concepts, antecedents, results, and dimensions of convenience (Fassnacht and Koese 2006; Seiders et al. 2007). The original concept of convenience is simple but it has well developed with enriched contexts in e-commerce. Websites that are conveniently designed help customers a lot, and business is also smoothly facilitated. In turn, customers who experience convenience when purchasing from a website will have positive expectations about the business because of the time and effort they saved in transactions and the easy achievement of their goal. A conveniently designed website is one of the competencies of online shopping malls, which has also become the foundation of the development of trust for customers. From this, the following hypothesis is proposed: H3: Site convenience is positively associated with trust in online businesses. 3.3.2 Content relevance Relevance refers to the meaningful relation between two objects under a certain circumstance, which are engaged in a common activity and have a purpose (Allwood 1984). The two relevant objects are not simply related with each other but are meaningfully connected. In online businesses, this meaningful connection is practiced when a customer searches for relevant product information from data on the web. Customers with certain purchase purposes look for relevant product information because not all web data are relevant to customers. Hence, content relevance in this study would be defined as the meaningful relation between product information on the web and the customers whose purpose is finding product information about the product or service that he is interested in. For these reasons, content relevance how much the information on the web is relevant to the objective of the web browsing is considered important in online businesses. It was proposed as a sub-concept of information quality in Delone and Mcleans IS success Model (1992) and also considered as an important factor in web personalization (Tam and Ho 2006). A relevant web content enhances the accuracy and speed of information processing of the customers, thereby making the decision-making process more effective. Eventually, a relevant web content increases user acceptance (Tam and Ho 2006) and exerts a positive effect on the flow experience of the user (Jiang et al. 2009). Relevant web content, including product information, expectedly increases the positive expectation of customers regarding the business transaction. It helps customers make

Inf Syst Front

decisions faster and more accurately. In turn, customers will perceive the higher level of information quality on the web. From this, we propose the following hypothesis: H4: Content relevance is positively associated with trust in online businesses.

3.4.2 Web fraud Web fraud refers to a broad category of crimes conducted by online users through website transactions. Due to the impersonality, anonymity, and information asymmetry between online sellers and customers (Turban et al. 2010), the web environment is vulnerable to a variety of fraudulent acts, such as misrepresentation, failure to ship, and improper handling (Chua et al. 2007). Web fraud is different from a seller s typographical error or simple information mistake due to confusion; it refers to an intentional misconduct in a web-based business transaction to deceive customers. Auctions are commonly the settings where vast majority of online fraudulent acts are committed (Abbasi et al. 2010), but fraud can exist in any kind of website as long as economic exchange is conducted. Fraud presupposes the unethical motivation of the seller, so it obviously ruins relationship with customers. If customers perceive any kind of fraud or attempts of fraud, they will immediately feel alarmed regarding their transaction and worry about the damage associated with it. Fraud is different from unintended mistake of sellers because it is the vicious motivation, not incompetence, that hurts the customers. Based on this premise, we derive the following hypothesis. H6: Web fraud is positively associated with distrust in online businesses. 3.5 Antecedes of trust and distrust: Capability-based, relationship-affecting factors 3.5.1 Content truthfulness In an online shopping mall, the truthfulness of contents is defined as the level of closeness of the product information to the objective features of the product (Cukier et al. 2004). It refers to the perceived fulfillment level of the promise that the product is exactly the same as what customers see on the website, thereby serving as a badge of integrity that only a small gap exists between the expected and the real value (Rust et al. 1999). Truthful product information on the web helps customers easily find the products they are looking for and avoid making wrong decisions. The perceived truthfulness of web content is an encoded stimulus that represents the functionality and performance of the shopping mall. With the content on the web, customers examine the various features of product and interpret them as stimuli. Therefore, when they browse web information and feel that the content is truthful, this stimulus will be encoded as high content truthfulness. However, as described in the theory, once such stimulus is psychologically encoded into truthfulness, it starts to affect the cognition, emotions, and even the behavior of the person involved. Psychological

3.4 Antecedes of distrust: Relationship-affecting factors Distrust is formed when it is observed that the partner has bad motivations or does damage on purpose. Distrust can be defined as feelings of hurt, suspiciousness, or fear of a partner s intentions and future behavior. It is not based on capability or skill of a partner that can be objectively assessed; rather, it is more related to the sincerity and motivation to continue the relationship. Thus, relationshipaffecting factors (e.g., involvement and responsiveness) that show the motivation and intentions of a partner become the foundations of distrust (Goodman et al. 1995). 3.4.1 Customer involvement Customer involvement embraces the number and type of activities that a customer engages in together in the course of their regular economic transactions with organizations (Goodman et al. 1995). It determines the strength and depth of the relationship between the customer and the organization (Goodman et al. 1995). For example, the customers can increase their involvement level by actively participating in the service and product design. Tightening the feedback loop between consumption and product can also enhance customer involvement level (Lundkvist and Yakhlef 2004). The impersonality of online business makes customer involvement more difficult than in offline businesses. However, services such as special contract, active customization or refund flexibility, can increase the level of customer involvement between online sellers and customers. Customer involvement is a relationship-affecting factor that represents the total quality (strength and depth) of the relationship between the customer and the organization. Frequent involvement by the customers strengthens the bond between the customer and the seller or organization. Customers would intuitively feel that they have a good relationship with the sellers if they are fully acknowledged and deeply involved in business operations. These activities affect the customers in their affective dimension, that is, the greater the extent of the customers involvement, the greater their sense of control, thereby lessening fear and worry in their transactions. Based on this premise, we derive the following hypothesis. H5: Customer involvement is negatively associated with distrust in online businesses.

Inf Syst Front

interactions among individuals are complicated, but they have confirmative order in the process (Bandura 1986). Content with high truthfulness guides customers into maintaining a high trust level. Trust is a positive expectation about the future action of the partner. When the content on the web is truthful, the promise that the shopping mall will deliver the product as indicated will be met. This reflects integrity, which is an important source of trust (Vance et al. 2008). Generally and intuitively, if all product information on the web is accurate and truthful, customers will easily find the products they are looking for. This in turn leads to positive expectations about web transactions. Therefore, the following is hypothesized: H7: Content truthfulness is positively associated with trust in online businesses. On the contrary, untruthful web content evokes distrust. Distrust is a belief in the possible losses that can be incurred by one party. When a customer encounters untruthful product information, such as wrong size and different capacity, he is unable to estimate the product value accurately and proceeds to make an uncertain purchase decision. With inaccurate and unreliable product information, a customer runs the risk of not receiving the product he wants and facing the consequent risks in the transaction. When a transaction risk is perceived by a customer, fear for the transaction emerges (Cases 2002), causing the customer to worry about the product. Finally, he becomes suspicious about the competency and motivation of the seller and begins to form an obvious distrust of the seller. Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed. H8: Content truthfulness is negatively associated with distrust in online businesses. 3.5.2 Customer responsiveness Customer responsiveness refers to how quickly and sincerely sellers and organizations can respond to requests from customers (Homburg et al. 2007). In online businesses, responding to customers is vital because of the impersonality and anonymity of web transactions. To serve as substitutes for face-to-face enterprises, online businesses should put more effort in handling customer requests. For example, many reputable websites provide customer highly customized response systems, such as one-to-one email service. A highly responsive website can identify customer needs and wishes better than its competitors (Koufteros et al. 2005). This responsiveness is one of the factors that customers consider when evaluating sellers and the capability of a firm to manage their relationship with customers. Sellers who are highly responsive are considered stronger competitors; thus, a highly responsive website attracts more

customers. The competence of the responsive website makes a customer trust the website because it is perceived as being capable of satisfying the customers needs. A website that can provide constant competent service and never breaks a promise can easily gain the trust of customers. Based on this premise, we derive the following hypothesis. H9: Customer responsiveness is positively associated with trust in online businesses. Customer responsiveness also captures the affective dimension of customers because a highly responsive website can strengthen the bond between the site and customers (Gefen and Ridings 2002). Responses are made through social interactions. Social interaction can sooth anger and worry (Homburg et al. 2007), and eventually build a bond between the seller and the buyer. The more the seller interacts with his or her customers with good will, the stronger their bond will become, which will affect their relationship. The foregoing is a business approach aimed toward touching customers hearts. Such increased responsiveness will not only improve perception on the sites capability, but also soothe and relieve the concerns of customers through interaction. This strong impact of customer responsiveness on affective dimension of customers can reduce the fear and worry of customers regarding their transactions. Based on this premise, we derive the following hypothesis. H10: Customer responsiveness is negatively associated with distrust in online businesses. 4 Research methodology 4.1 Development of measures To test the hypotheses, a survey method is adopted and the items were developed as follows. For content relevance and online loyalty, we adopted the existing scales from major information systems and marketing studies (Cyr 2008; Jiang et al 2009; Tam and Ho 2006). We also specified that the subject of loyalty is the website, and not the person or seller. For site convenience, customer responsiveness and customer involvement, we referred to major literature (Berry et al. 2002; Dai et al. 2008; Seiders et al. 2007) and modified the items into the forms that were appropriate for the online business context. We carefully retained the original meaning of terms without losing their suitability in an online business context. For content truthfulness and website fraud, we selected keywords from the literature (Cukier et al. 2004; Radoilska 2008) and converted them into sentences that were appropriate for the online business context. For trust and distrust, we first abstracted keywords from the literature (Dimoka 2010; Luhmann 1979; Mcknight et al. 1998) and formulated sentences from the abstracted keywords. Then

Inf Syst Front

we carefully reviewed them to note whether the sentences clearly indicate if they are referring to a cognitive belief or an emotive feeling, because no prior study highlighted the cognitive aspect of trust and the emotive aspect of distrust. Initially, three to five items for each construct were developed. However, through a pilot study with undergraduate students in a major university in Korea and dropped some of the constructs due to their low content validities. After the pilot study, we arrived at three items for each construct, thereby resulting in 27 items in total. All the items are listed in the Appendix. 4.2 Survey procedure

depends on the availability of ticket and 2) we will look for another package which fits your request. Respondents should spend another 2 min to carefully read and understand these cases to answer customer responsiveness and involvement questions. All scales used in this study use ten points rather than seven because the former reflects a variety of opinions, generates greater sensitivity, and helps respondents avoid median values (Diamond 1999). Furthermore, many people are already familiar with the notion of rating something __out of 10, making the scale easier for the respondents to understand (Dawes 2008).

5 Data analysis and result For the survey, we built a package tour online shopping mall. The website showed around 10 types of package tours with all the necessary information about the tours. The site worked like a real online shopping mall, but no real transaction was available. The execution of the survey was outsourced from Embrain Co. (www.embrain.com), a large market research company in Korea with more than 1.8 million panels in various Asian countries. Embrain Co. invited respondents from their panel pool via e-mail. If they accepted the offer, they were guided to the website we built. The selected respondents were then guided as follows: First, they were asked to pretend that they were planning a summer vacation. Second, the respondents were asked to browse the website we built for at least 10 min. After browsing and before starting to answer the questions, respondents were asked to provide the price of the package that they were interested in to eliminate respondents who did not browse the website with full attention. Finally, they were allowed to click on the next page and start answering questions on various web features, trust concerns, and so on. For each question, the respondents were not allowed to proceed if they had answered too quickly. The survey undertook one more step before asking customer responsiveness and customer involvement questions, namely, it showed two exemplary cases of customer counseling as follows: 1) those who wish to change the date after they purchase the package and 2) those who wish to change the route of the package before purchase. Cases were taken from a popular web travel agency following general policies and rules. The answers were as follows: 1) it

Table 1 Profile of the respondents Gender Male Female Total Freq (%) 140 (50.2) 139 (49.8) 279 (100) Age 1929 3039 4049 5059 Total

Initially, 300 panels participated. A total of 279 data sets were used after outliers were screened. As shown in Table 1, most of the respondents have experienced online shopping and no significant gender and age bias is observed. 5.1 Measurement model Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to test the validity of the constructs. All statistics showed high levels of fit through the model (GFI 0 0.87, RMR 0 0.030, RMSEA 0 0.060, AGFI 0 0.82, NFI 0 0.97, CFI 0 0.99, normed chi-square 0 2.01, see Table 4). The internal consistency and convergent validity of the constructs were tested by examining the itemconstruct loading, composite reliability, and average variance extracted (AVE). As shown in Table 2, all items exhibit loading values higher than the recommended levels (0.7), the values of composite reliabilities higher than 0.7 (Nunnally and Bernstein 1994), and AVEs above 0.5 (Fornell and Larcker 1981). The discriminant validity was examined by comparing the square root of the AVE and the off-diagonal construct correlations. As summarized in Table 3, all square roots of the AVE are greater than the off-diagonal construct correlations in the corresponding rows and columns (Fornell and Larcker 1981). The correlations among constructs, which are almost all below 0.7, except for fraud-involvement (0.73) and loyalty-trust (0.71), indicate that multicollinearity is not a potentially serious problem in the model (Bagozzi et al. 1991). Finally, we checked for possible common method

Freq (%) 71 (25.4) 69 (24.7) 73 (26.2) 66 (23.7) 279 (100) Internet Shopping Experience None Once or twice From time to time Often Total Freq (%) 12 (4.3) 14 (5.0) 98 (35.1) 155 (55.6) 279 (100)

Inf Syst Front Table 2 Results of confirmatory factor analysis

Construct

Indicator

Standardized loading 0.9 0.95 0.92 0.94 0.96 0.92 0.89 0.95 0.95 0.91 0.97 0.91 0.93 0.94 0.95 0.91 0.95 0.94 0.9 0.9 0.89 0.94 0.98 0.97 0.9 0.96 0.97

Measurement error 0.18 0.09 0.15 0.12 0.08 0.15 0.22 0.1 0.1 0.18 0.05 0.17 0.13 0.11 0.1 0.17 0.09 0.11 0.19 0.19 0.21 0.11 0.04 0.06 0.19 0.07 0.07

Composite reliability 0.95

AVE (Average variance extracted) 0.86

Site Convenience

Content Relevance

Content Truthfulness

Customer Responsiveness Customer Involvement

Web Fraud

SC1 SC2 SC3 CR1 CR2 CR3 CT1 CT2 CT3 SR1 SR2 SR3 CI1 CI2 CI3 SM1 SM2 SM3 TR1 TR2 TR3 DT1 DT2 DT3 LO1 LO2 LO3

0.96

0.88

0.95

0.86

0.96

0.87

0.95

0.88

0.92

0.80

Trust

0.98

0.93

Distrust

0.96

0.89

Online Loyalty

0.95

0.86

variance using Harmans single-factor test (Podsakoff et al. 2003). This test shows the amount of spurious covariance shared among variables because of the common method (e.g., ambiguous wording) used in collecting data. An exploratory factor analysis of our items revealed six factors of which the eigen value is over 1. All six factors explain 83.86 % of the variance in constructs, with the first factor explaining 21.14 and the last factor explaining 10.33 of the total variance. These results indicate that our data are not likely compromised by the common method bias. 5.2 Structural model The structural model fit is tested with LISREL 8.71. As shown in Table 4, the all statistics of the model revealed an adequate fit level of the model (GFI 0 0.85, RMR 0 0.090, RMSEA 0 0.065, AGFI 0 0.81, NFI 0 0.97, CFI 0 0.98, normed chi-square 0 2.19). As shown in Fig. 2, trust has a strong, positive effect on customer loyalty (b 0 0.52, t 0 10.50, p <0.01), thus providing support for H1. Distrust also shows a significant negative effect on customer loyalty (b 0 0.43, t 0 9.35, p <0.01), which support H2. Site convenience shows a significant positive effect on trust ( b 0 0.19,

t 0 2.93, p <0.01), so H3 is supported. Content relevance also shows a significant effect on trust (b 0 0.32, t 0 4.40, p <0.01), so H4 is supported. However, impact of customer involvement on distrust is not significant (b 0 0.09, t 0 1.18, p >0.10), so H5 is not supported. Web fraud shows a negative effect on distrust ( b 0 0.53, t 0 6.52, p < 0.01), so H6 is supported. Content truthfulness shows positive and negative effects on trust (b 0 0.27, t 0 4.46, p <0.01) and on distrust (b 0 0.16, t 0 3.23, p <0.01) respectively, so H7 and H8 are supported. Customer responsiveness shows a positive effect on trust (b 0 0.12, t 0 2.46, p <0.10) but not significant effect on distrust (b 0 0.06, t 0 1.22, p >0.10), so H9 is supported while H10 is not. In total, eight out of the ten hypotheses are supported as summarized in Table 5. In order to observe the mediating effect of trust and distrust, we compared the original model with an alternative model that hypothesizes the direct effect of antecedents to loyalty. The chi-square value of the model hypothesizing the direct effects of convenience, relevance, truthfulness, and responsiveness to loyalty is 647.18 (295). The differences in chi-square value with the d.f. between the original and alternative models are not sufficient to support a statement that there is a significant improvement in goodness-of-fit in

Inf Syst Front Loyalty

0.90 0.60a 0.71a

Trust

the alternative model. Moreover, all the paths of convenience, relevance, truthfulness, and responsiveness to loyalty are insignificant, thereby indicating the full mediating effect of trust. Similar results are also obtained from the alternative model testing of a mediation effect of distrust, which indicates that the chi-square value is 651.49 (295). In addition, all the paths from of truthfulness, responsiveness, involvement, and fraud to loyalty are insignificant, thereby indicating the full mediating effect of distrust. 5.3 A post-hoc analysis on alternative model

Distrust

Fraud

0.94 0.55a 0.64a 0.48a

0.96 0.69a

0.94

The bold numbers in the diagonal row are square roots of the average variance extracted

Table 3 Correlations of the latent variables and evidence of discriminant validity

Relevance

To explore the effects of various antecedents of trust and distrust, we develop an alternative model hypothesizing associations between the antecedents and the mediators (trust and distrust), as shown in Fig. 3 and Table 6. The statistics of the alternative model reveal adequate fit (GFI 0 0.86, RMR 0 0.041, RMSEA 0 0.061, AGFI 0 0.82, NFI 0 0.97, CFI 0 0.98, normed chi-square 0 2.04). Comparing the original and alternative models, the following conclusions are reached. Among the newly proposed hypotheses, the paths from involvement to trust and from fraud to trust are significant. Among the existing hypotheses, the paths from responsiveness to trust and from truthfulness to distrust are insignificant. Five antecedents with six significant associations are also found. Four antecedents (i.e., convenience, relevance, truthfulness, and involvement) are associated only with trust, whereas fraud is associated with both trust and distrust. It is different from the original model that fraud and involvement predict trust. This implies that trust can be formed to relieve the emotional concerns of the customers. Also, most antecedents are closely associated with trust rather than distrust. Trust has a more sensitive reaction to exogenous factors than distrust, possibly because for most of the consumers, trust is still a more important and critical issue than distrust.

Involvement

Responsiveness

Truthfulness

0.94 0.56a 0.20a 0.19a 0.30a 0.60a 0.30a 0.45a

0.93 0.15b 0.18a 0.26a 0.53a 0.31a 0.41a

0.93 0.38a 0.35a 0.25a 0.31a 0.27a

0.94 0.73a 0.43a 0.52a 0.40a

Convenience

6 Discussion 6.1 Summary of results The results of analyzed data show that both trust and distrust have strong positive and negative effects on customer loyalty. Four types of antecedents for trust (i.e., site convenience, content relevance, content truthfulness, and customer responsiveness) are identified, whereas two types of antecedents for distrust (i.e., content truthfulness and web fraud) are identified. Only truthfulness has an effect on both trust and distrust, whereas responsiveness only affects trust. Among the antecedents of trust, relevance and truthfulness show relatively stronger effects on trust than do convenience and responsiveness. Customers are more sensitive to the quality of information (i.e., contents) than to the functionality of

0.93 0.63a 0.47a 0.19a 0.17a 0.25a 0.52a 0.28a 0.42a

Convenience Relevance Truthfulness Responsiveness Involvement Fraud Trust Distrust Loyalty

Construct

Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

a

Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

Means (S.D.)

6.30 6.52 6.50 5.72 5.78 3.80 6.57 4.18 5.79

(1.78) (1.72) (1.50) (1.83) (1.85) (1.70) (1.41) (1.90) (1.85)

Inf Syst Front Table 4 Overall statistics of the structural model

Fit index

Recommended level

Measurement model

Structural model

Absolute Fit Measures Chi-square test statistic (2); df p-value Goodness-of fit index (GFI) Root mean square error of app. (RMSEA) Root mean squared residual (RMR) Incremental Fit Measures Adjusted goodness-of-fit index (AGFI) Normed fit index (NFI) Non-normed fit index (NNFI) Comparative fit index (CFI) Parsimonious Fit Measure Normed chi-square >0.05 >0.80 <0.08 <0.05 >0.80 >0.90 >0.90 >0.90 1.00~3.00 579.38;288 0.0000 0.87 0.060 0.030 0.82 0.97 0.98 0.99 2.01 653.50;299 0.0000 0.85 0.065 0.090 0.81 0.97 0.98 0.98 2.19

the site. Whether the information is relevant and truthful (i.e., information quality) is more critical in building trust than whether the site is functioning well. Unlike expectation, customer responsiveness and customer involvement do not affect distrust. Rather, website fraud is found to be the key antecedent of distrust. This result implies that the factors directly harming customer welfare, such as lies and deception, are the significant causes of distrust rather than the functional factors, such as responsiveness and involvement. One interesting point in this result is the relative position of trust compared with distrust. All of the antecedents of trust are found to be significant, whereas only two out of four antecedents of distrust are significant. Trust has four antecedents of which impact (beta coefficient) varies from 0.12 to 0.32, whereas distrust has two antecedents of which impacts are 0.16 (truthfulness) and 0.53 (Fraud), respectively. These results imply that consumer trust level is influenced by various exogenous factors in a shared manner, whereas distrust is critically influenced by fewer factors. Furthermore, the

Fig. 2 Results of the LISREL run

impacts of antecedents show that trust and distrust have different managerial implications. 6.2 Theoretical contributions The contributions of this research to the literature on trust and distrust are multifaceted. First, the psychological aspects of trust and distrust are discussed with theoretical foundation. There have been several attempts to differentiate trust from distrust (McKnight and Choudhury 2006; Sitkin and Roth 1993), but their differences in terms of psychological aspects have not been fully and sufficiently explored. Discussions on the psychological aspects of trust and distrust provide a theoretical lens with which to look into the minds of human beings and their different responses to various outer stimuli. It also allows for an in-depth understanding of why individuals behave the way they do in certain situations. The present study not only proposes the psychological characteristics of trust and distrust, but further identifies their

Inf Syst Front Table 5 Hypotheses test results Hypotheses H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 H7 H8 H9 H10 Trust Customer Loyalty Distrust Customer Loyalty Site convenience Trust Content Relevance Trust Consumer Involvement Distrust Web Fraud Distrust Content Truthfulness Trust Content Truthfulness Distrust Customer Responsiveness Trust Customer Responsiveness Distrust Result Supported Supported Supported Supported Not Supported Supported Supported Supported Supported Not Supported

varied antecedents to highlight the difference. The study also investigates the mindset of customers in terms of trust and distrust and shows how they consider both thinking (i.e., cognition) and feeling (i.e., affect) in their decision-making bases, particularly when building trust and/or distrust. Second, in the conceptualization of trust and distrust, this study accordingly identifies various web features that are important in building trust and distrust. Although previous research has identified various antecedents of trust and distrust (Cyr 2008), this study provides a differentiated implication by theorizing these antecedents based on whether they are capability oriented or relationship oriented. In addition, characterizing the antecedents based on their orientation in capability or relationship adds significance because both capability and relationship have been considered crucial factors in online business (Srinivasan and Moorman 2005). These further provide foundation on how the antecedents are related to trust and/or distrust. Six out of eight hypotheses on the antecedents are supported, and five out of six proposed antecedents are found to be significant, implying that there are still rooms to investigate further on these psychological aspects of trust and distrust. However, by selecting

Fig. 3 Results of the alternative model analysis

antecedents of trust and distrust based on their generic characteristics and theoretical significance, the present study shows how trust and distrust can emerge in online business. Lastly, this study emphasizes the mediating roles of trust and distrust in the formation of customer loyalty. Although customer loyalty is, without a doubt, an important objective of business, its relationship with trust and distrust has not been fully explained in prior studies. Customer loyalty is an externally observable factor for customers repeatedly purchasing from the same business. However, how customers repeated behavior can be linked to both trust, which is a cognitive factor, and distrust, which is an affective factor, has not been discussed in previous literature. Hence, by hypothesizing and testing the parallel relationships of trust and distrust with customer loyalty, this study enriches the theoretical background of customer loyalty and shows how constructs with different psychological statuses can influence the behaviors of customers through patterns. 6.3 Practical implications This study also provides important implications. First, the study shows how online shopping mall managers can evoke trust and avoid distrust concurrently. Both trust and distrust are crucial factors in online business because one accelerates business whereas the other blocks business transactions. Although the fact that trust and distrust are separate is widely accepted, independent notions that are not necessarily opposite each other, how trust and distrust should be managed differently has not been well known to practitioners. Hence, the present study shows what factors affect building trust and distrust, and how they mediate customer loyalty. For example, the study shows that harmful motivation of the seller (website fraud) is the most critical factor in the emergence of distrust, and information quality (content relevance and truthfulness) is the most effective factor in building trust. This result implies that even if the quality of information is high, if customers feel

Inf Syst Front Table 6 Comparison of original and alternative models Path Convenience Trust Convenience Distrust Relevance Trust Relevance Distrust Truthfulness Trust Truthfulness Distrust Responsiveness Trust Responsiveness Distrust Involvement Trust Involvement Distrust Fraud Trust Fraud Distrust Original model Significant Not hypothesized Significant Not hypothesized Significant Significant Significant Not significant Not hypothesized Not significant Not hypothesized Significant Alternative model/Path loading (t-value) Significant / 0.16** (2.7) Not significant / 0.04 (0.55) Significant / 0.31** (4.58) Not significant / 0.07 (0.93) Significant / 0.21** (3.88) Not significant / 0.10 (1.77) Not significant / 0.02 (0.43) Not significant / 0.05 (0.90) Significant / 0.14* (1.99) Not significant / 0.11 (1.42) Significant / 0.27** (3.68) Significant / 0.5** (6.11) Comparison No change No change No change No change No change Becomes insignificant Becomes insignificant No change Becomes significant No change Becomes significant No change

**Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed) *Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed)

insecure with the intrinsic motivation of the seller, customer loyalty will not be built easily. Second, this study discusses how customer loyalty can be increased through effective management, mediated by trust and distrust, of various website functions and relationships with customers. Customer loyalty has been an issue of interest for practitioners for a long time because it is one of the most effective and reliable strategies for profitability (Cyr 2008). This study shows how all web functions and features, with their psychological maps, can contribute to increased loyalty through the dynamics of trust and distrust. For example, this study concludes that trust and distrust are both crucial in building customer loyalty. Moreover, unlike expectation, customer involvement is found to be an insignificant factor in distrust building. It is possibly because of the generic constraints in online business that customers are not able to have face-to-face communications with sellers. Instead, the strong effects of web fraud and truthfulness show that online customers have high standard for sellers in their honesty and morality. Through these analyses, the present study shows how an organization can acquire and keep loyal customers effectively. 6.4 Limitations and future research This study has several limitations that should be considered in future research. First, this study did not capture the emotive aspect of trust and the cognitive aspect of distrust. We did not include them in our research scope because the main focus of our work is to emphasize the cognitive characteristics of trust and emotive aspects of distrust. However, this disregard of the aspects does not eliminate the possibility of the existence of a cognitive part of distrust and an affective part of trust. A number of studies have investigated the other aspects of trust.

Thus, further investigation on other components of trust and distrust (e.g., emotive trust and cognitive distrust) is expected to be of significant value in future research. Second, future research should identify more factors in capability-based and relationship-affecting elements. Six antecedents of trust and distrust with eight hypotheses were proposed, but only six of them were significant. Although all trust antecedents show a significant relationship with trust, only two antecedents show a significant relationship with distrust. Hence, future research should identify more antecedents that show a significant relationship with distrust.

7 Conclusion This study identifies the characteristics of trust and distrust in online businesses by focusing on their psychological differences. As proposed, trust is a cognitively active construct, whereas distrust is an emotively active construct. This psychological difference causes trust and distrust to respond differently to various outer stimuli and to mediate differently to customer loyalty. Six antecedents in three categories are tested on their relationships with trust and distrust to show the antecedents effects on, as well as the different characteristics of, trust and distrust. The survey results confirm their different paths to trust and distrust, which is the main idea of the study. As the study investigates the psychological aspects of trust and distrust, validation is conducted by testing their relationships with a variety of outer stimuli and making inferences from the results of these tests. Overall, the present study shows the different dynamics of trust and distrust in an online business context with theoretical foundations, which have not been fully discussed in the past.

Inf Syst Front

Appendix

Table 7 Measurement instruments trust and distrust Construct Trust Indicator TR1 TR2 TR3 Distrust DT1 Keywords Integrity Positive expectation Confidence Afraid of damage Key reference Mcknight et al. 2002, Gefen et al. 2003a, b Flavin et al. 2006; Lewicki et al. 1998; Questionnaires I believe that the Web site will provide the services as expected. I have positive expectations regarding this Web sites provision of service. I can transact with the Web site with confidence. I am afraid of the damage the future business conduct of this website may bring. I am suspicious that this website will respond to my interest in the product with vicious intentions. I worry that this website might not care about my business. Supporting references Lewicki et al. 1998; Luhmann 1979; Flavin et al. 2006; Mcknight et al. 2002, Dimoka 2010 Gefen et al. 2003a, b McKnight and Choudhury 2006

DT2

Suspiciousness

Dimoka 2010

DT3

Not caring

McAllister 1995

Table 8 Measurement instruments convenience, relevance, truthfulness, involvement, responsiveness, fraud and loyalty Construct Capability-based Factors Website Convenience Content Relevance Indicator Questionnaires CV1 CV2 CV3 RL1 RL2 RL3 RelationshipContent affecting Factors Truthfulness TF1 TF2 TF3 It does not take long to find the information I need from this website. The website is convenient to use. I do not have to spend much effort to find the information I need. The product information on the web is relevant to my task objective. The product information on the web is meaningfully connected to my interest. The product information on the web is closely related to what I am looking for. The information in the website is true. The information in the website does not contain any false information. The information in the website does not include any omission or distortion. The Web site seems to respond quickly when a customer requests change regarding the service. The Web site seems to be responsive to customers requests. The Web site seems to react immediately to customers requests. This site seems to support customer involvement in package service planning and design. I think I can become involved in package service planning and design if I wanted to. If customers suggest ideas related to the package service, these would be reflected in their design. The business certificate for the international travel agency shown on the Web site does not look genuine. The business partners shown on the Web site, including travel insurance companies, do not look genuine. The escrow service company shown on the Web site does not look genuine. I will visit this website again when I need to make a purchase, even though there are many other similar websites. If I need to make a purchase, this website will be my first choice. I believe that this is my favorite retail website among others. References Berry et al. 2002; Dai et al. 2008; Seiders et al. 2007 Tam and Ho 2006; Jiang et al 2009

Cukier et al. 2004; Radoilska 2008

Customer CR1 Responsiveness CR2 CR3 Capability-based, Customer CI1 relationshipInvolvement affecting Factors CI2 CI3 Website Fraud WF1 WF2 WF3 Customer Loyalty CL1 CL2 CL3

Gefen and Ridings 2002; HomBurg et al. 2007 Goodman et al. 1995; Lundkvist, A., & Yakhlef 2004

Abbasi et al. 2010; Chua et al. 2007

Cyr 2008; Flavin et al. 2006

Inf Syst Front

References

Abbasi, A., Zhang, Z., Zimbra, D., Chen, H., & Nunamaker, J. F., Jr. (2010). Detecting fake websites: the contribution of statistical learning theory. MIS Quarterly, 34(3), 128. Allwood, J. (1984). On relevance in spoken interaction. In Bckman and Kjellmer (Ed.), Papers on Language and Literature, (pp. 18 35), Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis. Assael, H. (1992). Consumer behavior and marketing action (4th ed.). Boston: PWS-Kent Publishing Company. Awad, N., & Ragowsky, A. (2008). Establishing trust in electronic commerce through online word of mouth: an examination across genders. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(4), 101121. Aydin, S., & zer, G. (2005). The analysis of antecedents of customer loyalty in the Turkish mobile telecommunication market. European Journal of Marketing, 39(7), 910925. Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Phillips, L. W. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Administrative Science Quarterly, 36(3), 421458. Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action . Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. Barney, J., & Hansen, M. (1994). Trustworthiness as a source of competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 15(3), 175190. Berkowitz, L. (1993). Towards a general theory of anger and emotional aggression: Implications of the cognitive- neoassociationistic perspective for the analysis of anger and other emotions. In R. S. Wyer & T. K. Srull (Eds.), Advances in social cognition (Vol. 6, pp. 146). Hillsdale: Erlbaum. Berry, L. L., Seiders, K., & Grewal, D. (2002). Understanding service convenience. Journal of Marketing, 66(3), 117. Bhatnagar, A., Misra, S., & Rao, H. R. (2000). Online risk, convenience, and internet shopping behavior. Communications of the ACM, 43(11), 98105. Bigley, G. A., & Pearce, J. L. (1998). Straining for shared meaning in organization science: problems of trust and distrust. Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 405422. Cases, A. (2002). Perceived risk and risk-reduction strategies in Internet shopping. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research, 12(4), 375394. Chang, H. H., & Chen, S. W. (2009). Consumer perception of interface quality, security, and loyalty in electronic commerce. Information & Management, 46(7), 411417. Cho, J. (2006). The mechanism of trust and distrust formation and their relational outcome. Journal of Retailing, 82(1), 2535. Chua, C., Wareham, J., & Robey, D. (2007). The role of online trading communities in managing Internet auction fraud. MIS Quarterly, 31(4), 759781. Chua, R. Y. J., Ingram, P., & Morris, M. (2008). From the head and the heart: locating cognition- and affect-based trust in managers professional networks. Academy of Management Journal, 51(3), 436452. Cukier, W., Bauer, R., & Middleton, C. (2004). Applying Habermas validity claims as a standard for Critical Discourse Analysis. In B. Kaplan, D. P. Truex, T. Wood-Harper, & J. I. DeGross (Eds.), Information systems research: Relevant theory and informed practice (pp. 233258). Norwell: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Cyr, D. (2008). Modeling website design across cultures: relationships to trust, satisfaction and E-loyalty. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(4), 4772. Dai, H., Salam, A.F. & King, R. (2008). Service convenience and relational exchange in electronic mediated environment: an empirical investigation. ICIS 2008 Proceedings. Paper 63. Dawes, J. (2008). Do data characteristics change according to the number of scale points used - an experiment using 5-point, 7-

point and 10-point scales. International Journal of Market Research, 50(1), 63. DeLone, W. H., & McLean, E. R. (1992). Information systems success: the quest for the dependent variable. Information Systems Research, 3(1), 6095. Diamond, L. (1999). Developing democracy: Toward consolidation. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. Dimoka, A. (2010). What does the brain tell us about trust and distrust? Evidence from a functional neuroimaging study. MIS Quarterly, 34(2), 373396. Fassnacht, M., & Koese, I. (2006). Quality of electronic services: conceptualizing and testing hierarchical model. Journal of Service Research, 9(1), 1937. Flavin, C., Guinalu, M., & Gurrea, R. (2006). The role played by perceived usability, satisfaction and consumer trust on website loyalty. Information and Management, 43(1), 114. Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 3950. Fredrickson, B. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218226. Gefen, D., & Ridings, C. M. (2002). Implementation team responsiveness and user evaluation of customer relationship management: a quasi-experimental design study of social exchange theory. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(1), 4763. Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003a). Inexperienced and experienced with online stores: the importance of TAM and trust. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 50 (3), 307321. Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003b). Trust and TAM in online shopping: an integrated model. MIS Quarterly, 27(1), 51 90. Goodman, P. S., Fichman, M., Lerch, F. J., & Snyder, P. R. (1995). Customer-firm relationship, involvement, and customer satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 38(5), 13101324. Grovier, T. (1994). An epistemology of trust. International Journal of Moral Social Studies, 8(2), 155174. Harris, L. C., & Goode, M. M. H. (2004). The four levels of loyalty and the pivotal role of trust: a study of online service dynamics. Journal of Retailing, 80(2), 139158. Hoch, S. J., & Loewenstein, G. F. (1991). Time-inconsistent preferences and consumer self-control. Journal of Consumer Research, 17, 492507. Homburg, C., Grozdanovic, M., & Klarmann, M. (2007). Responsiveness to customers and competitors: the role of affective and cognitive organizational systems. Journal of Marketing, 71(3), 1838. Jeffries, F. L., & Reed, R. (2000). Trust and adaptation in relational contracting. Academy of Management Review, 25(4), 873882. Jiang, C., Lim, K.H., Sun, Y. & Peng, Z. (2009). Does content relevance lead to positive attitude toward websites? exploring the role of flow and goal specificity, AMCIS 2009 Proceedings. Paper 727. Johnson, D., & Grayson, K. (2005). Cognitive and affective trust in service relationships. Journal of Business Research, 58(4), 500 507. Keller, K. L. (1993). Conceptualizing, measuring, and managing customer-based brand equity. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 1 22. Kim, D. (2008). Self-perception-based versus transference-based trust determinants in computer-mediated transactions: a cross-cultural comparison study. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(4), 1345. Komiak, S., & Benbasat, I. (2008). A two-process view of trust and distrust building in recommendation agents: a process-tracing study. Journal of Association for Information Systems, 9(12), 727747.

Inf Syst Front Koufteros, X., Vonderembse, M., & Jayaram, J. (2005). Internal and external integration for product development: the contingency effects of uncertainty, equivocality, and platform strategy. Decision Sciences Journal, 36(1), 97133. Lee, J.-N., & Choi, B. (2011). Effects of initial and ongoing trust in IT outsourcing: a bilateral perspective. Information & Management, 48(2), 96105. Lewicki, R. J., McAllister, D. J., & Bies, R. J. (1998). Trust and distrust: new relationships and realities. Academy of Management Review, 23 (3), 438458. Luhmann, N. (1979). Trust and power. Chichester: Wiley. Lundkvist, A., & Yakhlef, A. (2004). Customer involvement in new service development: a conversational approach. Managing Service Quality, 14, 249257. Mas-Colell, A., Winston, M.D. & Green, J.R. (1995). Microeconomic theory. Oxford University Press. McAllister, D. J. (1995). Affect and cognition-based trust as foundations for interpersonal cooperation in organizations. Academy of Management Journal, 38(1), 2459. McKnight, D.H. & Choudhury, V. (2006). Distrust and trust in B2C ecommerce: do they differ? In Proceedings of ICEC, 482491. McKnight, D. H., Cummings, L. L., & Chervany, N. L. (1998). Initial trust formation in new organizational relationships. The Academy of Management Review, 23(3), 473490. McKnight, D. H., Choudhury, V., & Kacmar, C. (2002). Developing and validating trust measures for e-commerce: an integrative typology. Information Systems Research, 13(3), 334359. Mischel, W., & Shoda, Y. (1995). A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychological Review, 102, 246 268. Moorman, C., Deshpande, R., & Zaltman, G. (1993). Factors affecting trust in market research relationships. Journal of Marketing, 57(1), 81101. Morrow, J. L., Jr., Hansen, M. H., & Pearson, A. W. (2004). The cognitive and affective antecedents of general trust within cooperative organizations. Journal of Managerial Issues, 16, 4864. Nielson Report, February 2008 Trends in Online Shopping a global Nielsen consumer report http://www.asiaing.com/trends-inonline-shopping-a-global-nielsen-consumer-report.html, Accessed on 28 Aug 2010. Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63(4), 3344. Pavlou, P. A., & Gefen, D. (2004). Building effective online marketplaces with institution-based trust. Information Systems Research, 15(1), 3759. Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. M., Lee, J., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method variance in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879903. Radoilska, L. (2008). Truthfulness and business. Journal of Business Ethics, 79(1), 2128. Rempel, J. K., Holmes, J. G., & Zanna, M. P. (1985). Trust in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49 (1), 95112. Ridings, C. M., Gefen, D., & Arinze, B. (2002). Some antecedents and effects of trust in virtual communities. Journal of Strategic Information Systems, 11(34), 271295. Russell, J. A. (2003). Core affect and the psychological construction of emotion. Psychological Review, 110(1), 145172. Rust, R. T., Inman, J. I., Jia, J., & Zahorik, A. (1999). What you dont know about customer-perceived quality: the role of customer expectation distributions. Marketing Science, 18(1), 7792. Seiders, K., Berry, L. L., & Gresham, L. (2000). Attention retailers: how convenient is your convenience strategy? Sloan Management Review, 49(3), 7990. Seiders, K., Voss, G. B., Godfrey, A. L., & Grewal, D. (2007). SERVCON: development and validation of a multidimensional service convenience scale. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(1), 144156. Sirdeshmukh, D., & Singh, J. (2002). Consumer trust, value, and loyalty in relational exchanges. Journal of Marketing., 66(1), 1537. Sitkin, S. B., & Roth, N. L. (1993). Explaining the limited effectiveness of legalistic remedies for trust/distrust. Organization Science, 4(3), 367392. Srinivasan, R., & Moorman, C. (2005). Strategic firm commitments and rewards to customer relationship management investments in online retailing. Journal of Marketing, 69, 193200. Srinivasan, S. S., Anderson, R., & Ponnavolu, K. (2002). Customer loyalty in e-commerce: an exploration of its antecedents and consequences. Journal of Retailing, 78(1), 4150. Tam, K. Y., & Ho, S. Y. (2006). Understanding the impact of web personalization on user information processing and decision outcomes. MIS Quarterly, 30(4), 865890. Turban, E., Lee, J.K., Liang, T.-P. & Turban, D. (2010). Electronic commerce: A managerial perspective, Prentice Hall. Vance, A., Elie-dit-Cosaque, C., & Straub, D. (2008). Examining trust in information technology artifacts: the effects on system quality and culture. Journal of Management Information Systems, 24(4), 73100. Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1984). Negative affectivity: the disposition to experience negative aversive emotional states. Psychological Bulletin, 96, 465490. Zajonc, R. B. (1980). Feeling and thinking: preferences need no inferences. American Psychologist, 35, 151175.

Jung Lee is an Assistant Professor in the Bang College of Business at KIMEP University. She was a post-doctoral research fellow in the Department of Information Systems at the National University of Singapore. She received Ph.D. degree in MIS from Korea University Business School, M.S. degree in Information Systems from the Graduate School of Information of Yonsei University, and B.S. degree in Biology from Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST). Her research interests include electronic word-of-mouth, trust/distrust and social media. She has published papers in Decision Support Systems, Information & Management and International Journal of Electronic Commerce, and presented papers at the ICIS, AMCIS, and PACIS Conferences. Jae-Nam Lee is a Professor in the Business School of the Korea University in Seoul, Korea. He was formerly on the faculty of the Department of Information Systems at the City University of Hong Kong. He holds MS and Ph.D. degrees in MIS from the Graduate School of Management of the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology (KAIST). His research interests are IT outsourcing, knowledge management, information security management, e-commerce, and IT deployment and impacts on organizational performance. His published research articles appear in MIS Quarterly, Information Systems Research, Journal of MIS, Journal of the AIS, Communications of the AIS, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, European Journal of Information Systems, Communications of the ACM, Information & Management, and others. He is currently serving on the editorial board of Journal of the AIS, Pacific Asia Journal of the AIS, and Electronic Commerce Research and Applications.

Inf Syst Front Bernard C.Y. Tan (http://www.comp.nus.edu.sg/~btan) is Professor of Information Systems and Vice Provost (Education) at the National University of Singapore (NUS). He received his Ph.D. in information systems from NUS. He has been a Visiting Scholar in the Graduate School of Business at Stanford University and the Terry College of Business at the University of Georgia. He has received university teaching and research awards at NUS. He is a Fellow and a past President of the Association for Information Systems (AIS). He has served on the editorial boards of MIS Quarterly (senior editor), Journal of the AIS (senior editor), IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management (department editor), Management Science (associate editor), ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems (associate editor), and Journal of Management Information Systems. His research has been published in journals such as ACM Transactions on ComputerHuman Interaction, ACM Transactions on Information Systems, ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems, IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, IEEE Transactions on Systems, Man and Cybernetics, Information Systems Research, Journal of Management Information Systems, Journal of the AIS, Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, Management Science, and MIS Quarterly. His current research interests are social media, virtual communities, and knowledge management.

You might also like

- Concept MapDocument1 pageConcept MapLesley Joy T. BaldonadoNo ratings yet

- Tori TheoryDocument16 pagesTori TheoryJigar Undavia100% (2)

- Subiect Bilingv 2019 PDFDocument2 pagesSubiect Bilingv 2019 PDFAnthony AdamsNo ratings yet

- Engleza - Bilingv Engleza CL A 9 A Subiect - Barem PDFDocument3 pagesEngleza - Bilingv Engleza CL A 9 A Subiect - Barem PDFAnthony AdamsNo ratings yet

- What Is FashionDocument6 pagesWhat Is FashionArim Arim100% (3)

- Mathematics of InvestmentsDocument2 pagesMathematics of InvestmentsShiera Saletrero SimbajonNo ratings yet

- Trust Establishment Concept in Business Relationship: A Literature Analysis Fausta Ari BarataDocument17 pagesTrust Establishment Concept in Business Relationship: A Literature Analysis Fausta Ari BarataNur FajriyahNo ratings yet

- Newarticle18socialaug12 PDFDocument12 pagesNewarticle18socialaug12 PDFdanikapanNo ratings yet

- Research BodyDocument5 pagesResearch BodyDianaRoseAcupeadoNo ratings yet

- Interpersonal Trust and Its Role in OrganizationsDocument7 pagesInterpersonal Trust and Its Role in OrganizationssafiraNo ratings yet

- Seppanen Revison 2006Document17 pagesSeppanen Revison 2006gimejiafNo ratings yet

- What Does The Brain Tell Us About Trust and Distrust? Evidence From A Functional Neuroimaging StudyDocument24 pagesWhat Does The Brain Tell Us About Trust and Distrust? Evidence From A Functional Neuroimaging StudyNisa AssyifaNo ratings yet

- Ona 3Document19 pagesOna 3jyothisaiswaroop satuluriNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Engineering Research and Development (IJERD)Document8 pagesInternational Journal of Engineering Research and Development (IJERD)IJERDNo ratings yet

- Transformational and Helping BehaviorDocument21 pagesTransformational and Helping BehaviorNaufal RamadhanNo ratings yet