Professional Documents

Culture Documents

History 1700 Research Paper

History 1700 Research Paper

Uploaded by

api-241872399Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

History 1700 Research Paper

History 1700 Research Paper

Uploaded by

api-241872399Copyright:

Available Formats

SALT LAKE COMMUNITY COLLEGE

A UNITED FRONT

SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR CLARK IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE COMPLETION OF HISTORY 1700

BY MASON HESS

SALT LAKE CITY, UTAH APRIL 21, 2014

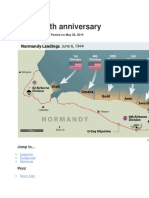

On June 6, 1994, in a united offensive display of valor, the Allied troops of ground, sea, and air broke through the door that would eventually lead to the fall of the Axis powers. These men, in combined effort, made possible one of the greatest victories that has ever been seen in war, but at the loss of many brotherly casualties. Though this valiant battle for the beaches of Normandy ended in success, it would not have been so without the necessary cooperation of allied forces from every conceivable route of attack. These brave men knew the devastation that lay wait for them on that ominous beachhead, but that did not take away their morale that drove them to victory. The battle for Normandy, would soon become known as the battle that shaped the world. According to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, the invasion that took place on D-day, otherwise known as operation Overlord, was undoubtedly the most complicated and difficult that has ever taken place.1 This proved to be true throughout the process of the invasion. As the date of the invasion had initially been postponed due to inclement weather off the shores of France, the seas remained wavy and choppy and the air remained windy. This posed many difficulties for the airborne troops and those that arrived by sea. With reluctance, and more casualties than anticipated or hoped for, our airborne and wave riding troops arrived at the coastline of Normandy France under heavy defensive fire from the Nazis. Early in the morning, as the sun rose, C-47s arrived at the French coast to reinforce the airborne troops (who were the first to land).1 These 20,000 landing craft were described by General Dwight D. Eisenhower to be instrumental in the allied victory.1 Simultaneously, as the sun rose, a fleet of destroyers and gunships, filled with men ready to storm the shores and occupy the beachhead,

Mark Bowden, Our Finest Day: D-day (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2002), 2-19.

plowed through the choppy waters of the English Channel.1 The greatest amphibious assault in history was underway. Operation Overlord ended up involving approximately 2 million allied soldiers, sailors, airmen, and civilians.2 It was about 156,000 men who were expected to reach the shores in the first 24 hours of the invasion and most of this combat power mobilized by sea. The allies compiled an immense fleet of nearly 7,000 vessels, which included a requirement of a massive naval personnel group for the operation of twelve hundred war ships along with fifteen hospital ships to care for the injured.2 The first combat formations on the beaches of France would come by glider and paratrooper and were comprised of three divisions, the U.S. 82nd and 101st airborne, and the British 6th. The three divisions numbered more than 23,000 men and paved the way for the 75,000 British and Canadian troops who trailed them by just a few hours.2 Alongside their allied brothers, some 54,400 American G.Is would rush the beaches on D-day. Ed Ruggero, author of The First Men In, also concluded that there had never been an amphibious invasion like this one (and thanks to the development of nuclear weaponsthere will never be another.)2 He ended this portion of writing with a mesmerizing quote that brings the realization of the danger of defeat and the notion that was on the mind of all involved in the assault, saying, Failure was utterly unthinkable yet entirely possible.2 This notion coincides with all of the authors and soldiers perspectives of the battle for Normandy. They all perceived that D-day would be a bad day for a lot of young men, as paratrooper Dewitt Lowery said in Marcus Brothertons book We Who Are Alive and Remain.3

Ed Ruggero, The First Men In: U.S. Paratroopers and the Fight to Save D-Day (New York: HarperCollins, 2006), 8283. 3 Marcus Brotherton, We Who Are Alive and Remain: Untold Stories from the Band of Brothers (New York: Berkley Caliber/Penguin Group, 2009), 99-114.

Brotherton compiled quotes from many soldiers talking about their preparation for the invasion. They all describe the days and hours before the D-day invasion as being filled with tension and nervousness and one soldier in particular, Rod Bain, who was an infamous member of Easy Company, said concerning D-day and the preparation up to, its all a nightmare.3 Many of these men who were interviewed for this book speak of tragic landings, which were miles away from their targeted drop zones, separating them from the rest of their company. There is a name that is repeated quite often throughout the interviews, Winters. Major Dick Winters became the commander of Easy Company by surviving the jump that his commander did not. According to Winters account, which was very similar to the accounts given by the men interviewed in We Who Are Alive and Remain, only ten out of eighty-one planes had found their drop zone marks, three of them missing their marks by up to twenty miles. This scattered Easy Company across a wide dispersal area several miles west of their objective.4 Many soldiers of the airborne Easy Company never found their way back to their division or to the commanding Major Winters as Ed Pepping recalled in Brothertons book, I never did make it back to my unit. The last thing I remember was being in Carentan with three others, walking headlong through town in an attempt to reach E Company.3 For the airborne troops, the scattering abroad of their divisions was a distinct and demoralizing event that separated their experiences from those who arrived by sea, who faced other troubles, though the geographical strategy was still on the side of those who stormed the beach, because they had planned for the beachfront assault. Normandy was a strategic turning point that was extremely vital to sway the advantage in favor of the allies. As historian Arthur Davies describes, the beaches of "Normandy offered the necessary favorable combination of

Richard D. Winters and Cole C. Kingseed, Beyond Band of Brothers (New York: Berkley Caliber, 2006), 80-85.

military and geographical factors."5 Davies defense was that even though America lost many men due to what seemed to be problematic transportation issues and axis firepower, Normandy was the spot that was most susceptible and vulnerable to invasion. By strategically pin pointing Operation Overlord at Normandy, American troops stayed far away from the possibility of a quick German counterattack that would have come from Rhineland, which Davies describes as a "solar plexus of German military strength."5 By applying knowledge of the German tactical response, American troops avoided, what Davies called a "spider web of railroads and roads leading from Paris to the channel ports," which could have allowed the Germans easy transportation for reinforcements, possibly bringing our cause to naught. Normandy was targeted, because it was far from the main German beachhead. America cut of the German supply lines from Ruhr with relentless Allied air support, which meant that they were forced to maintain and ration long lines of communication, as well as low supplies of petrol.5 Even though the airborne troops were scattered abroad an expansive area of land, they were still able to occupy the attention of the Nazis. This allowed the American troops that arrived by sea to rush the beach at Normandy without the focus of the German defenses being solely directed at them, ultimately leading to a cooperative victory that would not have taken place without the efforts of soldiers from all disciplines of the American military. On a different note, the account of Orval W. Wakefield gives a unique interpretation of what happened that day, though as D-day progressed, he gained what he called a marginalized perspective of the operation. Orval was part of a navy combat demolition unit (NCDU) and

Davies, Arthur. Geographical Factors in the Invasion and Battle of Normandy, Geographical Review, Vol. 36, No. 4 (Oct., 1946), pp. 613-631

was one of the first of, what we know today as, frogmen.6 When he first arrived via an amphibious transport vehicle and got out of the landing craft, making his way toward the beach, he realized that his equipment held him down to the extend he percieved he would not even make it to the beach. He thought, maybe I was a coward, to himself.6 Orval describes the business of the beaches of Normandy as the business of a small city as the sky lit up with gunfire to create, what he described as, being brighter than any fourth of July celebration he had ever seen. As they drew near to the completion of their goal with minimal casualties, he had a moment to think and he reflected on the moment when he was in the water struggling with his equipment and wondering if he was a coward, when I realized I wasnt, it was a great feeling.6 He also said, in contrast to many other sources and accounts, that June 6 turned out to be a pretty good day for the men of NCDU 132.6 Orvals marginalized perception came from his understanding that the other NCDU units at Utah beach had suffered 30 percent casualties and 70 percent at Omaha beach. He said his unit was lucky to have lost only two of their eight men. He believed that his most important thought on that day was this: Yes, I could do the job I had volunteered to do.6 This is a significant notion because it promotes a vital contribution to the success of the invasion, as a whole, and that it was only brought to fruition by the successes of individual units such as Orvals. Stephen E. Ambrose defends this notion of individual successes leading to the successful completion of Operation Overlord in the book Pegasus Bridge. He describes a daring mission, so crucial that, had it failed, the entire invasion of Normandy may have fallen to the same fate. Ambrose goes through the months, then through minute by minute description of the preparation leading up to the invasion. Ambrose gives great detail of the contribution of the British airborne,

6

Paul Stillwell, ed., Assault On Normandy: First-Person Accounts from the Sea Services (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1994), 93-96.

specifically their attack at Pegasus Bridge. A glider-borne unit of the British 6th Airborne Division, commanded by Major John Howard, was to land, take the bridges intact and hold them until relieved. The successful taking of the bridges played an important role in limiting the effectiveness of a German counter-attack to the invasion. The bridge was renamed Pegasus, coinciding with the emblem sported by those of the British 6th Airborne.7 This is yet another presentation of a smaller, successful operation that greatly contributed to the Normandy invasion and the success of D-day in its entirety. It is now seen, through undeniable evidence, the importance and significance of each troops role that was played on that day. Whether American or British, airborne or infantry, pilot or amphibious vehicle operator, the combined efforts of all these led to a victory that resembled no other in history. Joseph Balkoski said it best: D-day now belonged to the ages: Politicians had conceived it; generals had planned it; thousands of anonymous fighting men had executed it; and historians would define and interpret it.8 The invasion had worked, but only due to the cooperative effort displayed by each individual units completion of their given task. As GIs from infantry divisions met up with airborne paratroopers after the successful assault of D-day, the amphibious war that they had trained for so long for came to a sudden end, as a new one began. D-day was the beginning of the prosperous struggle that Americans had been told would eventually lead to Hitlers downfall. 8 The battle for the beaches of Normandy was successful, and the door to a global victory for the Allies had been opened.

7 8

Stephen E. Ambrose, Pegasus Bridge: June 6, 1944 (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1985), 1-182. Joseph Balkoski, Utah Beach: the Amphibious Landing and Airborne Operations On D-Day, June 6, 1944 (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2005), 301.

Bibliography Primary Sources Ambrose, Stephen E. Pegasus Bridge: June 6, 1944. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1988. Balkoski, Joseph Utah Beach: The Amphibious Landing and Airborne Operations On D-Day, June 6, 1944. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 2005. Bowden, Mark. Our Finest Day: D-day. San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2002. Brotherton, Marcus. We Who Are Alive and Remain: Untold Stories from the Band of Brothers. New York: Berkley Caliber/Penguin Group, 2009. Ruggero, Ed. The First Men In: U.s. Paratroopers and the Fight to Save D-Day. New York: Harper, 2006. Stillwell, Paul, ed. Assault On Normandy: First-Person Accounts from the Sea Services. Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 1994. Winters, Richard D., and Cole C. Kingseed. Beyond Band of Brothers. New York: Berkley Caliber, 2006. Secondary Source Davies, Arthur. Geographical Factors in the Invasion and Battle of Normandy, Geographical Review, Vol. 36, No. 4 (Oct., 1946), pp. 613-631

You might also like

- Under The Crescent Moon: Rebellion in Mindanao By: Marites Danguilan Vitug and Glenda M. GloriaDocument2 pagesUnder The Crescent Moon: Rebellion in Mindanao By: Marites Danguilan Vitug and Glenda M. Gloriaapperdapper100% (2)

- Playbook: Game Desig N byDocument48 pagesPlaybook: Game Desig N byMat K100% (2)

- Auguries of InnocenceDocument8 pagesAuguries of InnocenceHafiz AhmedNo ratings yet

- Hand GrenadesDocument148 pagesHand GrenadesAngel Curiel100% (2)

- HoTE Colonials3Document6 pagesHoTE Colonials3Blake RadetzkyNo ratings yet

- Destroyers At Normandy: Naval Gunfire Support At Omaha Beach [Illustrated Edition]From EverandDestroyers At Normandy: Naval Gunfire Support At Omaha Beach [Illustrated Edition]No ratings yet

- War Stories of D-Day: Operation Overlord: June 6, 1944From EverandWar Stories of D-Day: Operation Overlord: June 6, 1944Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Churchill's D-Day: The British Bulldog’s Fateful Hours During the Normandy InvasionFrom EverandChurchill's D-Day: The British Bulldog’s Fateful Hours During the Normandy InvasionNo ratings yet

- Men of Steel: Canadian Paratroopers in Normandy, 1944From EverandMen of Steel: Canadian Paratroopers in Normandy, 1944Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Torpedo Junction: U-Boat War Off America's East Coast, 1942From EverandTorpedo Junction: U-Boat War Off America's East Coast, 1942Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (17)

- Invasion '44: The Full Story of D-DayFrom EverandInvasion '44: The Full Story of D-DayRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (4)

- The Story of Wake Island [Illustrated Edition]From EverandThe Story of Wake Island [Illustrated Edition]Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Wwii Origins Newsela pt3Document4 pagesWwii Origins Newsela pt3api-273260229No ratings yet

- Untold Stories from World War II Rhode IslandFrom EverandUntold Stories from World War II Rhode IslandRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Battle of Midway Research PaperDocument8 pagesBattle of Midway Research Paperxdhuvjrif100% (1)

- Operation Cobra and the Great Offensive: Sixty Days That Changed the Course of World War IIFrom EverandOperation Cobra and the Great Offensive: Sixty Days That Changed the Course of World War IIRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (3)

- Force Mulberry - The Planning and Installation of Artificial Harbor Off U.S. Normandy Beaches in World War IIFrom EverandForce Mulberry - The Planning and Installation of Artificial Harbor Off U.S. Normandy Beaches in World War IINo ratings yet

- D Day LandingsDocument24 pagesD Day LandingsRadu Tavsance100% (2)

- D-Day 1944 (3): Sword Beach & the British Airborne LandingsFrom EverandD-Day 1944 (3): Sword Beach & the British Airborne LandingsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- The Victory at Sea: American Destroyers in Action, Decoying Submarines to Destruction, The American Mine Barrage in the North Sea, German Submarines Visit the American Coast, The Navy Fighting on the LandFrom EverandThe Victory at Sea: American Destroyers in Action, Decoying Submarines to Destruction, The American Mine Barrage in the North Sea, German Submarines Visit the American Coast, The Navy Fighting on the LandNo ratings yet

- D Day Research PaperDocument5 pagesD Day Research Paperqirnptbnd100% (1)

- The D-Day Companion: Leading Historians explore history’s greatest amphibious assaultFrom EverandThe D-Day Companion: Leading Historians explore history’s greatest amphibious assaultJane PenroseNo ratings yet

- The Decoys: A Tale of Three Atlantic Convoys, 1942From EverandThe Decoys: A Tale of Three Atlantic Convoys, 1942Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Decisive Moments in History: D-Day & Operation OverlordFrom EverandDecisive Moments in History: D-Day & Operation OverlordRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Resurrection: Salvaging the Battle Fleet at Pearl HarborFrom EverandResurrection: Salvaging the Battle Fleet at Pearl HarborRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- D-Day: Juno Beach, Canada's 24 Hours of DestinyFrom EverandD-Day: Juno Beach, Canada's 24 Hours of DestinyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Shepherds of the Sea: Destroyer Escorts in World War IIFrom EverandShepherds of the Sea: Destroyer Escorts in World War IIRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Voices from D-Day: Eyewitness Accounts from the Battle for NormandyFrom EverandVoices from D-Day: Eyewitness Accounts from the Battle for NormandyNo ratings yet

- SNEAK PEEK: Fremantle's Submarines: How Allied Submariners and Western Australians Helped To Win The War in The PacificDocument15 pagesSNEAK PEEK: Fremantle's Submarines: How Allied Submariners and Western Australians Helped To Win The War in The PacificNaval Institute Press100% (1)

- The U.S. Coast Guard in World War IIFrom EverandThe U.S. Coast Guard in World War IIRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- The U.S. Army Campaigns: Normandy: World War II: 6 June–24 July 1944From EverandThe U.S. Army Campaigns: Normandy: World War II: 6 June–24 July 1944No ratings yet

- SURVIVOR: USS Russell a World War Two DestroyerFrom EverandSURVIVOR: USS Russell a World War Two DestroyerRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Long Voyage: America's Merchant Marine in World War IIFrom EverandLong Voyage: America's Merchant Marine in World War IIRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Maritime DisasterDocument16 pagesMaritime DisasterAzureen MurshidiNo ratings yet

- Cordon of SteelDocument57 pagesCordon of SteelBob Andrepont100% (2)

- D Day Airborne BridgeheadDocument30 pagesD Day Airborne Bridgeheadpaul murphyNo ratings yet

- D-Day 75th Anniversary: Daily News ArticleDocument9 pagesD-Day 75th Anniversary: Daily News ArticleMK PCNo ratings yet

- Canadian Operations in The Battle of NormandyDocument11 pagesCanadian Operations in The Battle of NormandyBrian CalebNo ratings yet

- Patton and His Third Army (Annotated)From EverandPatton and His Third Army (Annotated)Rating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (2)

- Nothing Friendly in the Vicinity ...: My Patrols on the Submarine USS Guardfish During WWIIFrom EverandNothing Friendly in the Vicinity ...: My Patrols on the Submarine USS Guardfish During WWIIRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- The Battle to Save the Houston: October 1944 to March 1945From EverandThe Battle to Save the Houston: October 1944 to March 1945No ratings yet

- Liberating Europe: D-Day to Victory in Europe, 1944–1945From EverandLiberating Europe: D-Day to Victory in Europe, 1944–1945Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- The Dieppe Raid: The Allies’ Assault Upon Hitler’s Fortress Europe, August 1942From EverandThe Dieppe Raid: The Allies’ Assault Upon Hitler’s Fortress Europe, August 1942No ratings yet

- Grey Wolf, Grey Sea: Aboard the German Submarine U-124 in World War IIFrom EverandGrey Wolf, Grey Sea: Aboard the German Submarine U-124 in World War IIRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Operation Alacrity: The Azores and the War in the AtlanticFrom EverandOperation Alacrity: The Azores and the War in the AtlanticRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- History of KoreaDocument18 pagesHistory of KoreaGeraldin Buyagao KinlijanNo ratings yet

- Firearms in America 1600 - 1800Document308 pagesFirearms in America 1600 - 1800Mike100% (6)

- Bob Harvey-Tork & Grunt's Guide To Effective Negotiations-Marshall Cavendish Limited (2008)Document209 pagesBob Harvey-Tork & Grunt's Guide To Effective Negotiations-Marshall Cavendish Limited (2008)sherisplat6036No ratings yet

- Relic Nemesis RulebookDocument20 pagesRelic Nemesis RulebookJose Manuel Mujica SantanaNo ratings yet

- Khulfa-E-Rashideen: Made By: Tahreem IkramDocument23 pagesKhulfa-E-Rashideen: Made By: Tahreem IkramSaba MukhtarNo ratings yet

- Complicit ManagementDocument17 pagesComplicit ManagementSagirNo ratings yet

- Infographic BlackDocument1 pageInfographic Blackapi-312329159No ratings yet

- +27780171131 ( ) UNIVERSAL SSD CHEMICAL SOLUTION AND ACTIVATION POWDER IN SOUTH AFRICA, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Australia, New Zealand, GHANA, UgandaDocument2 pages+27780171131 ( ) UNIVERSAL SSD CHEMICAL SOLUTION AND ACTIVATION POWDER IN SOUTH AFRICA, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Australia, New Zealand, GHANA, Ugandajona tumukundeNo ratings yet

- History Essay MwhiteDocument2 pagesHistory Essay MwhitejaconNo ratings yet

- Groups What Are The Characteristics of A Group?Document5 pagesGroups What Are The Characteristics of A Group?Mohamed AbdulsamadNo ratings yet

- USTPAC Remembers 30 Anniversary of "Black July"-A State-Abetted Pogrom Against Tamils in Sri LankaDocument2 pagesUSTPAC Remembers 30 Anniversary of "Black July"-A State-Abetted Pogrom Against Tamils in Sri Lankaapi-208594819No ratings yet

- Abstract HondaDocument4 pagesAbstract HondaVishwanathan IyerNo ratings yet

- Ate Hazel - Final DemoDocument8 pagesAte Hazel - Final DemoJomz MagtibayNo ratings yet

- Kt8-Corpseshore Cobras - Delaque GangDocument16 pagesKt8-Corpseshore Cobras - Delaque Gangmarcusarelius64No ratings yet

- Stages of Group DevelopmentDocument7 pagesStages of Group DevelopmentochioreanuNo ratings yet

- San Miguel vs. Khan (Valera)Document2 pagesSan Miguel vs. Khan (Valera)ASGarcia24No ratings yet

- Marx's Conflict Theory (Reading)Document5 pagesMarx's Conflict Theory (Reading)JAN CAMILLE OLIVARESNo ratings yet

- Pang-Et VS ManacnesDocument1 pagePang-Et VS ManacnesrengieNo ratings yet

- Worksheet BullyingDocument3 pagesWorksheet BullyingSofiane Iaiche-achourNo ratings yet

- UCSPDocument30 pagesUCSPKzelle Patawaran0% (1)

- Sir Creek DisputeDocument6 pagesSir Creek DisputeSport EntertainingNo ratings yet

- Bibliography TaiwanDocument6 pagesBibliography Taiwan13leejNo ratings yet

- Extended Essay February Cesar Landin 2403vg5Document20 pagesExtended Essay February Cesar Landin 2403vg5IvanaNo ratings yet

- The Quails: ScriptDocument4 pagesThe Quails: ScriptAnnisa Septiani SyahvianaNo ratings yet

- Conflicts of IntrestDocument11 pagesConflicts of IntrestDRx Sonali TareiNo ratings yet

![Destroyers At Normandy: Naval Gunfire Support At Omaha Beach [Illustrated Edition]](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/293575085/149x198/eadaa76007/1617234264?v=1)

![The Story of Wake Island [Illustrated Edition]](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/259898855/149x198/25b54cc76a/1627937575?v=1)