Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Philosophy Paper

Philosophy Paper

Uploaded by

tigrrrr0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

45 views52 pagesIt has philosophy stuff

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentIt has philosophy stuff

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

45 views52 pagesPhilosophy Paper

Philosophy Paper

Uploaded by

tigrrrrIt has philosophy stuff

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 52

American Economic Association

Time Discounting and Time Preference: A Critical Review

Author(s): Shane Frederick, George Loewenstein and Ted O'Donoghue

Source: Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. 40, No. 2 (Jun., 2002), pp. 351-401

Published by: American Economic Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2698382 .

Accessed: 10/04/2014 02:22

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

American Economic Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal

of Economic Literature.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Journal of Economic Literature

Vol. XL (June 2002), pp. 351-401

T ime Discounting and T ime

Preference: A C ritical R ev iew

SHA NE FR EDER IC K, GEOR GE LOEWENST EIN,

and T ED O'DONOGHUE'

1. Introd uction

I NT ER T EMPOR A L C HOIC ES-d ecisions

inv olv ing trad eoffs among costs and

benefits occurring at d ifferent times-

are important and ubiquitous. Such d eci-

sions not only affect one's health, w ealth,

and happiness, but, may also, as A d am

Smith first recognized , d etermine the

economic prosperity of nations. In this

paper, w e rev iew empirical research on

intertemporal choice, and present an

ov erv iew of recent theoretical formula-

tions that incorporate insights gained

from this research.

Economists' attention to intertempo-

ral choice began early in the history of

the d iscipline. Not long after A d am

Smith called attention to the impor-

tance of intertemporal choice for the

w ealth of nations, the Scottish economist

John R ae w as examining the sociologi-

cal and psychological d eterminants of

these choices. In section 2, w e briefly

rev iew the perspectiv es on intertempo-

ral choice of R ae and nineteenth- and

early tw entieth-century economists, and

d escribe how these early perspectiv es

interpreted intertemporal choice as

the joint prod uct of many conflicting

psychological motiv es.

A ll of this changed w hen Paul Sam-

uelson proposed the d iscounted -utility

(DU) mod el in 1937. Despite Samuel-

son's manifest reserv ations about the

normativ e and d escriptiv e v alid ity of

the formulation he had proposed , the

DU mod el w as accepted almost in-

stantly, not only as a v alid normativ e

stand ard for public policies (e.g., in cost-

benefit analyses), but as a d escriptiv ely

accurate representation of actual behav -

ior. A central assumption of the DU

mod el is that all of the d isparate mo-

tiv es und erlying intertemporal choice can

be cond ensed into a single parameter-

the d isc.ount rate. In section 3 w e exam-

ine this and many other assumptions

und erlying the DU mod el. We d o not

present an axiomatic d eriv ation of the

mod el, but instead focus on those

features that highlight the implicit

psychological assumptions und erlying

the mod el.

1

Fred erick: Sloan School of Management, Mas-

sachusetts Institute of T echnology. Loew enstein:

Department of Social and Decision Sciences,

C arnegie Mellon Univ ersity. O'Donoghue: De-

partment of Economics, C ornell Univ ersity. We

thank C olin C amerer, Dav id Laibson, John

McMillan, Drazen Prelec, Daniel R ead , Nachum

Sicherman, Duncan Simester, and three anony-

mous referees for useful comments. We thank

C ara. Barber, R osa Blackw ood , Mand ar Oak, and

R osa Stipanov ic for research assistance. For finan-

cial support, Fred erick and Loew enstein thank the

Integrated Stud y of the Human Dimensions of

Global C hange at C arnegie Mellon Univ ersity

(NSF Grant SBR -9521914), and O'Donoghue

thanks the National Science Found ation (A w ard

SE'S-0078796).

351

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

352 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XL (June 2002)

Samuelson's reserv ations about the

d escriptiv e v alid ity of the DU mod el

w ere justified . Section 4 rev iew s

the grow ing list of "DU anomalies"-

patterns of choice that are inconsistent

w ith the mod el's theoretical pred ic-

tions. Virtually ev ery assumption und er-

lying the DU mod el has been tested

and found to be d escriptiv ely inv alid in

at least some situations. Moreov er, as

w e d iscuss at the end of the section,

these anomalies are not anomalies in the

sense that they are regard ed as errors

by the people w ho commit them. Unlike

many of the better-know n expected -

utility anomalies, the DU anomalies d o

not necessarily v iolate any stand ard or

principle that people believ e they

should uphold .

T he insights about intertemporal

choice gleaned from this empirical re-

search hav e led to the proposal of nu-

merous alternativ e theoretical mod els,

w hich w e rev iew in section 5. Some of

these mod ify the d iscount function, per-

mitting, for example, d eclining d iscount

rates or "hyperbolic d iscounting." Oth-

ers introd uce ad d itional arguments into

the utility function, such as the utility

of anticipation. Still others d epart from

the DU mod el more rad ically, by in-

clud ing, for instance, systematic mis-

pred ictions of future utility. Many of

these new theories rev iv e psychological

consid erations d iscussed by R ae and

other early economists that w ere extin-

guished w ith the ad option of the DU

mod el and its expression of intertem-

poral preferences in terms of a single

parameter.

In section 6, w e rev iew attempts to

estimate d iscount rates. While the DU

mod el assumes that people are charac-

terized by a single d iscount rate, this

literature rev eals spectacular v ariation

across (and ev en w ithin) stud ies. T he

failure of this research to conv erge to-

w ard any agreed -upon av erage d iscount

rate stems partly from d ifferences in

elicitation proced ures. But it also stems

from the faulty assumption that the v ar-

ied consid erations that are relev ant in

intertemporal choices apply equally to

d ifferent choices and thus that they can

all be sensibly represented by a single

d iscount rate.

T hroughout the paper, w e stress the

importance of d istinguishing among the

v aried consid erations that und erlie in-

tertemporal choices. We d istinguish

time d iscounting from time preference.

We use the term time d iscounting

broad ly to encompass any reason for

caring less about a future consequence,

includ ing factors that d iminish the ex-

pected utility generated by a future

consequence, such as uncertainty or

changing tastes. We use the term time

preference to refer, more specifically, to

the preference for immed iate utility

ov er d elayed utility. In section 7, w e

push this theme further, by examining

w hether time preference itself might

consist of d istinct psychological traits

that can be separately analyzed . Section

8 conclud es.

2. Historical Origins of the Discounted

Utility Mod el

T he historical d ev elopments that cul-

minated in the formulation of the DU

mod el help to explain the mod el's limi-

tations. Each of the major figures in the

d ev elopment of the DU mod el-John

R ae, Eugen v on B6hm-Baw erk, Irv ing

Fisher, and Paul Samuelson-built

upon the theoretical framew ork of his

pred ecessors, d raw ing on little more

than introspection and personal obser-

v ation. When the DU mod el ev entually

became entrenched as the d ominant

theoretical framew ork for mod eling in-

tertemporal choice, it w as d ue largely to

its simplicity and its resemblance to the

familiar compound interest formula,

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Fred erick, Loew enstein, and O'Donoghue: T ime Discounting 353

and not as a result of empirical research

d emonstrating its v alid ity.

Intertemporal choice became firmly

established as a d istinct topic in 1834,

w ith John R ae's publication of T he So-

ciological T heory of C apital. Like A d am

Smith, R ae sought to d etermine w hy

w ealth d iffered among nations. Smith

had argued that national w ealth w as d e-

termined by the amount of labor allo-

cated to the prod uction of capital, but

R ae recognized that this account w as in-

complete because it failed to explain

the d eterminants of this allocation. In

R ae's v iew , the missing element w as

"the effectiv e d esire of accumulation"-a

psychological factor that d iffered across

countries and d etermined a society's

lev el of sav ing and inv estment.

A long w ith inv enting the topic of in-

tertemporal choice, R ae also prod uced

the first in-d epth d iscussion of the psy-

chological motiv es und erlying inter-

temporal choice. R ae believ ed that

intertemporal-choice behav ior w as the

joint prod uct of factors that either pro-

moted or limited the effectiv e d esire of

accumulation. T he tw o main factors

that promoted the effectiv e d esire of

accumulation w ere the bequest motiv e

("the prev alence throughout the society

of the social and benev olent affections,"

p. 58) and the propensity to exercise

self-restraint ("the extent of the intel-

lectual pow ers, and the consequent

prev alence of habits of reflection, and

prud ence, in the mind s of the mem-

bers of society," p. 58). One limiting

factor w as the uncertainty of human

life:

When engaged in safe occupations, and liv ing

in healthy countries, men are much more apt

to be frugal, than in unhealthy, or hazard ous

occupations, and in climates pernicious to hu-

man life. Sailors and sold iers are prod igals.

In the West Ind ies, New Orleans, the East

Ind ies, the expend iture of the inhabitants is

profuse. T he same people, coming to resid e

in the healthy parts of Europe, and not get-

ting into the v ortex of extrav agant fashion,

liv e economically. War and pestilence hav e

alw ays w aste and luxury, among the other ev ils

that follow in their train. (R ae 1834, p. 57)

A second factor that limited the ef-

fectiv e d esire of accumulation w as the

excitement prod uced by the prospect of

immed iate consumption, and the con-

comitant d iscomfort of d eferring such

av ailable gratifications:

Such pleasures as may now be enjoyed gener-

ally aw aken a passion strongly prompting to

the partaking of them. T he actual presence of

the immed iate object of d esire in the mind by

exciting the attention, seems to rouse all the

faculties, as it w ere to fix their v iew on it, and

lead s them to a v ery liv ely conception of the

enjoyments w hich it offers to their instant

possession. (R ae 1834, p. 120)

A mong the four factors that R ae id en-

tified as the joint d eterminants of time

preference, one can glimpse tw o fund a-

mentally d ifferent v iew s. One, w hich w as

later championed by William S. Jev ons

(1888) and his son, Herbert S. Jev ons

(1905), assumes that people care only

about their immed iate utility, and ex-

plains farsighted behav ior by postulat-

ing utility from the anticipation of

future consumption. On this v iew , d e-

ferral of gratification w ill occur only if

it prod uces an increase in "anticipal"

utility that more than compensates for

the d ecrease in immed iate consumption

utility. T he second perspectiv e assumes

equal treatment of present and future

(zero d iscounting) as the natural base-

line for behav ior, and attributes the

ov erw eighting of the present to the

miseries prod uced by the self-d enial

required to d elay gratification. N. W.

Senior, the best-know n ad v ocate of this

"abstinence" perspectiv e, w rote, "T o

abstain from the enjoyment w hich is in

our pow er, or to seek d istant rather

than immed iate results, are among the

most painful exertions of the human

w ill" (Senior 1836, p. 60).

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

354 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XL (June 2002)

T he anticipatory-utility and absti-

nence perspectiv es share the id ea that

intertemporal trad eoffs d epend on im-

med iate feelings-in one case, the im-

med iate pleasure of anticipation, and in

the other, the immed iate d iscomfort of

self-d enial. T he tw o perspectiv es, how -

ev er, explain v ariability in intertemporal-

choice behav ior in d ifferent w ays. T he

anticipatory-utility perspectiv e attrib-

utes v ariations in intertemporal-choice

behav ior to d ifferences in people's

abilities to imagine the future and to

d ifferences in situations that promote

or inhibit such mental images. T he ab-

stinence perspectiv e, on the other hand ,

explains v ariations in intertemporal-

choice behav ior on the basis of ind iv id -

ual and situational d ifferences in the

psychological d iscomfort associated w ith

self-d enial. In this v iew , one should

observ e high rates of time d iscounting

by

people

w ho find it painful to d elay

gratification, and in situations in w hich

d eferral is generally painful e.g., w hen

one is, as R ae w ord ed it, in the "actual

presence of the immed iate object of

d esire."

Eugen v on Bohm-Baw erk, the next

major figure in the d ev elopment of the

economic perspectiv e on intertemporal

choice, ad d ed a new motiv e to the list

proposed by R ae, Jev ons, and Senior,

arguing that humans suffer from a

systematic tend ency to und erestimate

future w ants:

It may be that w e possess inad equate pow er

to imagine and to abstract, or that w e are not

w illing to put forth the necessary effort, but

in any ev ent w e limn a more or less incom-

plete picture of our future w ants and espe-

cially of the remotely d istant ones. A nd

then there are all those w ants that nev er

come to mind at all. (Bohm-Baw erk 1889, pp.

268-69)2

B6hm-Baw erk's analysis of time pref-

erence, like those of his pred ecessors,

w as heav ily psychological, and much of

his v oluminous treatise, C apital and

Interest, w as d ev oted to d iscussions of

the psychological constituents of time

preference. How ev er, w hereas the early

v iew s of R ae, Senior, and Jev ons ex-

plained intertemporal choices in terms

of motiv es that are uniquely associated

w ith time, B6hm-Baw erk began mod el-

ing intertemporal choice in the same

terms as other economic trad eoffs-as a

"technical" d ecision about allocating re-

sources (to oneself) ov er d ifferent points

in time, much as one w ould allocate

resources betw een any tw o competing

interests, such as housing and food .

B6hm-Baw erk's treatment of inter-

temporal choice as an allocation of con-

sumption among time period s w as for-

malized a d ecad e later by the A merican

economist Irv ing Fisher (1930). Fisher

plotted the intertemporal consumption

d ecision on a tw o-good ind ifference

d iagram, w ith consumption in the cur-

rent year on the abscissa, and consump-

tion in the follow ing year on the ord i-

nate. T his representation mad e clear

that a

person's

observ ed (marginal)

rate of time preference-the marginal

rate of substitution at her chosen con-

sumpti-on bund le-d epend s on tw o

consid erations: time preference and d i-

minishing marginal utility. Many econo-

mists hav e subsequently expressed d is-

comfort w ith using the term "time

preference" to includ e the effects of d if-

ferential marginal utility arising from

unequal consumption lev els betw een

time period s (see in particular Mancur

Olson and Martin Bailey 1981). In

Fisher's formulation, pure time prefer-

ence can be interpreted as the marginal

2

In a frequently cited passage from T he Eco-

nomics of Welfare, A rthur Pigou (1920) proposed

a similar account of time preference, suggesting

that it results from a type of cognitiv e illusion: "our

telescopic faculty is d efectiv e, and w e, therefore,

see future pleasures, as it w ere, on a d iminished

scale."

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Fred erick, Loew enstein, and O'Donoghue: T ime Discounting 355

rate of substitution on the d iagonal,

w here consumption is equal in both

period s.

Fisher's w ritings, like those of his

pred ecessors, includ ed extensiv e d iscus-

sions of the psychological d eterminants

of time preference. Like B6hm-Baw erk,

he ld ifferentiated "objectiv e factors,"

such as projected future w ealth and

risk, from "personal factors." Fisher's

list of personal factors includ ed the four

d escribed by R ae, "foresight" (the abil-

ity to imagine future w ants-the inv erse

of the d eficit that Bohm-Baw erk postu-

lated ), and "fashion," w hich Fisher be-

liev ed to be "of v ast importance . . . in

its influence both on the rate of interest

and on the d istribution of w ealth itself."

(Fisher 1930, p. 88):

T he most fitful of the causes at w ork is prob-

ably fashion. T his at the present time acts,

on the one hand , to stimulate men to sav e

and become millionaires, and , on the other

hand , to stimulate millionaires to liv e in an

ostentatious manner. (Fisher 1930, p. 87)

Hence, in the early part of the tw en-

tieth century, "time preference" w as

v iew ed as an amalgamation of v arious

intertemporal motiv es. While the DU

mod el cond enses these motiv es into the

d iscount rate, w e w ill argue that resur-

recting these d istinct motiv es is crucial

for und erstand ing intertemporal choices.

3. T he Discounted Utility Mod el

In 1937, Paul Samuelson introd uced

the DU mod el in a fiv e-page article

titled "A Note on Measurement of Util-

ity." Samuelson's paper w as intend ed to

offer a generalized mod el of intertem-

poral choice that w as applicable to mul-

tiple time period s (Fisher's graphical

ind ifference-curv e analysis w as d ifficult

to extend to more than tw o time peri-

od s) and to make the point that repre-

senting intertemporal trad eoffs re-

quired a card inal measure of utility. But

in Samuelson's simplified mod el, all the

psychological concerns d iscussed ov er the

prev ious century w ere compressed into

a single parameter, the d iscount rate.

T he DU mod el specifies a d ecision

maker's intertemporal preferences ov er

consumption profiles (C t,.. .,C T ). Und er

the usual assumptions (completeness,

transitiv ity, and continuity), such pref-

erences can be represented by an in-

tertemporal utility function Ut(C t,...,C T ).

T he DU mod el goes further, by as-

suming that a person's intertemporal

utility function can be d escribed by the

follow ing special functional form:

T

-

t

Ut(C t,...,C T )

=

E D(k)u(ct+ k)

k=O , k

w here D(k) =

l+p

In this formulation, U(C t+k) is often inter-

preted as the person's card inal instanta-

neous utility function-her w ell-being in

period t + k-and D(k) is often inter-

preted as the person's d iscount func-

tion-the relativ e w eight she attaches, in

period t, to her w ell-being in period t + k.

p represents the ind iv id ual's pure rate

of time preference (her d iscount rate),

w hich is meant to reflect the collectiv e

effects of the "psychological" motiv es

d iscussed in section 2.3

Samuelson d id not end orse the DU

mod el as a normativ e mod el of in-

tertemporal choice, noting that "any

connection betw een utility as d iscussed

here and any w elfare concept is d is-

av ow ed " (p. 161). He also mad e no

claims on behalf of its d escriptiv e v alid -

ity, stressing, "It is completely arbitrary

to assume that the ind iv id ual behav es so

as to maximize an integral of the form

env isaged in [the DU mod el]" (p. 159).

How ev er, d espite Samuelson's manifest

3T he continuous-time analogue is Ut({C tlt e [t,T ]) =

__t e

- P(

-

t)u(ct). For expositional ease, w e shall

restrict attention to d iscrete-time throughout.

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

356 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XL (June 2002)

reserv ations, the simplicity and ele-

gance of this formulation w as irresist-

ible, and the DU mod el w as rapid ly

ad opted as the framew ork of choice for

analyzing intertemporal d ecisions.

T he DU mod el receiv ed a scarcely

need ed further boost to its d ominance

as the stand ard mod el of intertemporal

choice w hen T jalling C . Koopmans

(1960) show ed that the mod el could be

d eriv ed from a superficially plausible

set of axioms. Koopmans, like Samuel-

son, d id not argue that the DU mod el

w as psychologically or normativ ely

plausible; his goal w as only to show that

und er some w ell-specified (though ar-

guably unrealistic) circumstances, in-

d iv id uals w ere logically compelled to

possess positiv e time preference. Pro-

d ucers of a prod uct, how ev er, cannot

d ictate how the prod uct w ill be used ,

and Koopmans' central technical mes-

sage w as largely lost w hile his axiom-

atization of the DU mod el helped to

cement its popularity and bolster its

perceiv ed legitimacy.

In the remaind er of this section, w e

d escribe some important features of the

DU mod el as it is commonly used by

economists, and briefly comment on the

normativ e and positiv e v alid ity of these

assumptions. T hese features d o not rep-

resent an axiom system-they are nei-

ther necessary nor sufficient cond itions

for the DU mod el-but are intend ed

to highlight the implicit psychological

assumptions und erlying the mod el.4

3.1 Integration of New A lternativ es

w ith Existing Plans

A central assumption in most mod els

of intertemporal choice-includ ing the

DU mod el-is that a person ev aluates

new alternativ es by integrating them

w ith her existing plans. T o illustrate,

consid er a person w ith an existing con-

sumption plan (C t,...,C T ) w ho is offered

an intertemporal-choice prospect X,

w hich might be something like an op-

tion to giv e up $5000 tod ay to receiv e

$10,000 in fiv e years. Integration means

that prospect X is not ev aluated in isola-

tion, but in light of how it changes the

person's aggregate consumption in all

future period s. T hus, to ev aluate the

prospect X, the person must choose w hat

her new consumption path

(C 't, .,C fT )

w ould be if she w ere to accept prospect

X, and should accept the prospect if

Ut(C 't, . .,C T )

>

Ut(ct.- * .,C T ).

A n alternativ e w ay to und erstand in-

tegration is to recognize that intertem-

poral prospects alter a person's bud get

set. If the person's initial end ow ment is

Eo, then accepting prospect X w ould

change her end ow ment to Eo u X. Let-

ting B(E) d enote the person's bud get

set giv en end ow ment E-i.e., the set of

consumption streams that are feasible

giv en end ow ment E-the DU mod el

says that the person should accept

prospect X if:

T

IC

-t

max

(,

C t

u(c)

(C t, ,C T )

e B(Eo U X) Xt yP )

T

m T t

> 'max

I;(

u

(c).

( C t, ,cT )

e B(Eo) X= t

While integration seems normativ ely

compelling, it may be too d ifficult to

actually d o. A person may not hav e

w ell-formed plans about future con-

sumption streams, or be unable (or un-

w illing) to recompute the new optimal

plan ev ery time she makes an intertem-

poral choice. Some of the ev id ence w e

rev iew below supports the plausible

presumption that people ev aluate the

results of intertemporal choices ind e-

pend ently of any expectations they hav e

4 T here are sev eral d ifferent axiom systems for

the DU mod el-in ad d ition to Koopmans, see

Peter Fishburn (1970), K. J. Lancaster (1963),

R ichard F. Meyer (1976), and Fishburn and A riel

R ubinstein (1982).

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Fred erick, Loew enstein, and O'Donoghue: T ime Discounting 357

regard ing consumption in future time

period s.

3.2 Utility Ind epend ence

T he DU mod el explicitly assumes that

the ov erall v alue-or "global utility"-

of a sequence of outcomes is equal to

the (d iscounted ) sum of the utilities in

each period . Hence, the d istribution of

utility across time makes no d ifference

beyond that d ictated by d iscounting,

w hich (assuming positiv e time prefer-

ence) penalizes utility that is experi-

enced later. T he assumption of utility

ind epend ence has rarely been d iscussed

or challenged , but its implications are

far from innocuous. It rules out any

kind of preference for patterns of utility

ov er time-e.g., a preference for a flat

utility profile ov er a roller-coaster util-

ity profile w ith the same d iscounted

utility.5

3.3 C onsumption Ind epend ence

T he DU mod el explicitly assumes that

a person's w ell-being in period t + k is

ind epend ent of her consumption in any

other period -i.e., that the marginal

rate of substitution betw een consump-

tion in period s t and T ' is ind epend ent

of consumption in period t".

C onsumption ind epend ence is analo-

gous to, but fund amentally d ifferent from,

the ind epend ence axiom of expected -

utility theory. In expected -utility the-

ory, the ind epend ence axiom specifies

that preferences ov er uncertain pros-

pects are not affected by the conse-

quences that the prospects share-i.e.,

that the utility of an experienced out-

come is unaffected by other outcomes

that one might hav e experienced (but

d id not). In intertemporal choice, con-

sumption ind epend ence says that pref-

erences ov er consumption profiles are

not affected by the nature of consump-

tion in period s in w hich consumption is

id entical in the tw o profiles-i.e., that

an outcome's utility is unaffected by

outcomes experienced in prior or future

period s. For example, consumption in-

d epend ence says that a person's prefer-

ence betw een an Italian and T hai res-

taurant tonight should not d epend on

w hether she had Italian last night, nor

w hether she expects to hav e it tomor-

row . A s the example suggests, and as

Samuelson and Koopmans both recog-

nized , there is no compelling rationale

for such an assumption. Samuelson

(1952, p. 674) noted that, "the amount

of w ine I d rank yesterd ay and w ill d rink

tomorrow can be expected to hav e ef-

fects upon my tod ay's ind ifference

slope betw een w ine and milk." Simi-

larly, Koopmans (1960, p. 292) acknow l-

ed ged that, "One cannot claim a high

d egree of realism for [the ind epen-

d ence assumption], because there is no

clear reason w hy complementarity of

good s could not extend ov er more than

one time period ."

3.4 Stationary Instantaneous Utility

When applying the DU mod el to spe-

cific problems, it is often assumed that

the card inal instantaneous utility func-

tion

u(c,)

is constant across time, so that

the w ell-being generated by any activ ity

is the same in d ifferent period s. Most

economists w ould acknow led ge that sta-

tionarity of the instantaneous utility

function is not sensible in many situ-

ations, because people's preferences d o,

in fact, change ov er time in pred ictable

5"Utility ind epend ence" has meaning only if

one literally interprets u(ct+k) as w ell-being expe-

rienced in period t + k. We believ e that this is, in

fact, the common interpretation. For a mod el that

relaxes the assumption of utility ind epend ence,

see Benjamin Hermalin and A lice Isen (2000),

w ho consid er a mod el in w hich w ell-being in

period t d epend s on w ell-being in period t - 1-

i.e., they assume ut = u(ct, ut-1). See also Daniel

Kahneman, Peter Wakker, and R akesh Sarin

(1997) w ho propose a set of axioms that w ould

justify an assumption of ad d itiv e separability in

instantaneous utility.

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

358 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XL (June 2002)

and unpred ictable w ays. T hough this

unrealistic assumption is often retained

for analytical conv enience, it becomes less

d efensible as economists gain insight

into how tastes change ov er time (see

Loew enstein and A ngner, forthcoming,

for a d iscussion of d ifferent sources of

preference change).6

3.5 Ind epend ence of Discounting

from C onsumption

T he DU mod el assumes that the d is-

count function is inv ariant across all

forms of consumption. T his feature is

crucial to the notion of time preference.

If people d iscount utility from d ifferent

sources at d ifferent rates, then the no-

tion of a unitary time preference is

meaningless. Instead w e w ould need to

label time preference accord ing to the

object being d elayed -"banana time

preference," "v acation time prefer-

ence," and so on. In section 7, w e d is-

cuss in more d etail the v alid ity of the

assumption that the same rate of time

preference applies to all forms of

consumption.

3.6 C onstant Discounting and T ime

C onsistency

A ny d iscount function can be w ritten in

the formD(k)

=

H-Ik I (l,w herepn rep-

resents the per-period d iscount rate

for period n-that is, the d iscount rate

applied betw een period s n and n + 1.

Hence, by assuming that the d iscount

function takes the form D(k) = K

kI

the DU mod el assumes a constant per-

period d iscount rate

(ppn

= p for all

n).

7

C onstant d iscounting entails an ev en-

hand ed ness in the w ay a person ev alu-

ates time. It means that d elaying or

accelerating tw o d ated outcomes by a

common amount should not change

preferences betw een the outcomes-if

in period t a person prefers X at X to Y

at t + d for some t, then in period t she

must prefer X at t to Y at t + d for all t.

T he assumption of constant d iscounting

permits a person's time preference to

be summarized as a single d iscount

rate. If constant d iscounting d oes not

hold , then characterizing one's time

preference requires the specification of

an entire d iscountfunction.

C onstant d iscounting implies that a

person's intertemporal preferences are

time-consistent, w hich means that later

preferences "confirm" earlier prefer-

ences. Formally, a person's preferences

are time-consistent if, for any tw o con-

sumption profiles (C t,.. .,C T ) and (C 't,...,C 'T ),

w ith ct = c't, Ut(ct,ct + 1,.. .,C T ) ? Ut(c't,C 't+ 1,

...,C /T ) if and only if Ut+1(ct+1,...,cT )

>

Ut+l(c't+1,...,C 'T ).8

For an

interesting

d is-

cussion that questions the normativ e v a-

lid ity of constant d iscounting, see Martin

A lbrecht and Martin Weber (1995).

3.7 Diminishing Marginal Utility

and Positiv e T ime Preference

While not core features of the DU

mod el, v irtually all analyses of intertem-

poral choice assume both d iminishing

6

A s w e d iscuss in section 5, end ogenous prefer-

ence changes, d ue to things such as habit forma-

tion or reference d epend ence, are best und erstood

in terms of consumption interd epend ence and not

nonstationary utility. In some situations, nonsta-

tionarities clearly play an important role in behav -

ior-e.g., Stev en Suranov ic, R obert Gold farb, and

T homas Leonard (1999), and O'Donoghue and

Mathew R abin (1999a; 2000) d iscuss the impor-

tance of nonstationarities in the realm of ad d ictiv e

behav ior.

7

A n alternativ e but equiv alent d efinition of con-

stant d iscounting is that D(k)/D(k + 1) is ind epen-

d ent of k.

8 C onstant d iscounting implies time-consistent

preferences only und er the ancillary assumption

of stationary d iscounting, for w hich the d is-

count function D(k) is the same in all period s. A s a

counterexample, if the period -t d iscount function

is

Dt(k)

=

(,+p)

w hile the

k

period -t + 1 d iscount

function is

Dt+l(k)

= (r+E1 for some p' ? p, then

the person exhibits cons ant d iscounting at both

d ates t and t + 1, but nonetheless has time-

inconsistent preferences.

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Fred erick, Loew enstein, and O'Donoghue: T ime Discounting 359

marginal utility (that the instantaneous

utility function u(ct) is concav e) and posi-

tiv e time preference (that the d iscount rate

p is positiv e).9 T hese tw o assumptions

create opposing forces in intertemporal

choice: d iminishing marginal utility mo-

tiv ates a person to spread consumption

ov er time, w hile positiv e time prefer-

ence motiv ates a person to concentrate

consumption in the present.

Since people d o, in fact, spread con-

sumption ov er time, the assumption of

d iminishing marginal utility (or some

other property that has the same effect)

seems strongly justified . T he assump-

tion of positiv e time preference, on the

other hand , is more questionable. Sev -

eral researchers hav e argued for posi-

tiv e time preference on logical ground s

(Jack Hirshleifer 1970; Koopmans 1960;

Koopmans, Peter A . Diamond , and

R ichard E. Williamson 1964; Olson and

Bailey 1981). T he gist of their argu-

ments is that a zero or negativ e time

preference, combined w ith a positiv e

real rate of return on sav ing, w ould

command the infinite d eferral of all

consumption.10 But this conclusion as-

sumes, unrealistically, that ind iv id uals

hav e infinite life-spans and linear (or

w eakly concav e) utility functions. Nev er-

theless, in econometric analyses of sav -

ings and intertemporal substitution, posi-

tiv e time preference is sometimes treated

as an id entifying restriction w hose v io-

lation is interpreted as ev id ence of

misspecification.

T he most compelling argument sup-

porting the-logic of positiv e time pref-

erence w as mad e by Derek Parfit (1971;

1976; 1982), w ho contend s that there is

no end uring self or "I" ov er time to

w hich all future utility can be ascribed ,

and that a d iminution in psychological

connections giv es our d escend ent fu-

ture selv es the status of other people-

making that utility less than fully

"ours" and giv ing us a reason to count it

less:11

We care less about our further future . . .

because w e know that less of w hat w e are

now -less, say, of our present hopes or plans,

lov es or id eals-w ill surv iv e into the further

future . . . [if] w hat matters hold s to a lesser

d egree, it cannot be irrational to care less.

(Parfit 1971, p. 99)

Parfit's claims are normativ e, not d e-

scriptiv e. He is not attempting to ex-

plain or pred ict people's intertemporal

choices, but is arguing that conclusions

about the rationality of time preference

must be ground ed in a correct v iew of

personal id entity. How ev er, if this is the

only compelling normativ e rationale for

time d iscounting, it w ould be instruc-

tiv e to test for a positiv e relation be-

tw een observ ed time d iscounting and

changing id entity. Fred erick (2002)

cond ucted the only stud y of this type,

9

Discounting is not inherent to the DU mod el,

because the mod el could be applied w ith p < 0.

How ev er, the inclusion of p in the mod el strongly

implies that it may take a v alue other than zero,

and the name d iscount rate certainly suggests that

it is greater than zero.

10

In the context of intergenerational choice,

Koopmans (1967) called this result the parad ox of

the ind efinitely postponed splurge. See also Ken-

neth J. A rrow (1983), S. C hakrav arty (1962), and

R obert M. Solow (1974).

11A s noted by Fred erick (2002), there is much

d isagreement about the nature of Parfit's claim. In

her rev iew of the philosophical literature, Jennifer

Whiting (1986, p. 549) i entifies four d ifferent in-

terpretations: (1) the strong absolute claim: that it

is irrational for someone to care about their future

w elfare, (2) the w eak absolute claim: that there is

no rational requirement to care about one's future

w elfare, (3) the strong comparativ e claim: that it is

irrational to care more about one's ow n future

w elfare than about the w elfare of any other per-

son, and (4) the w eak comparativ e claim: that one

is not rationally required to care more about their

future w elfare than about the w elfare of any other

person. We believ e that all of these interpretations

are too strong, and that Parfit end orses only a

w eaker v ersion of the w eak absolute claim. T hat is,

he claims only that one is not rationally required

to care about one's future w elfare to a d egree that

exceed s the d egree of psychological connected ness

that obtains betw een one's current self and one's

future self.

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

360 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XL (June 2002)

and found no relation betw een mone-

tary d iscount rates (as imputed from

proced ures such as "I w ould be ind iffer-

ent betw een $100 tomorrow and $-

in fiv e years") and self-perceiv ed stabil-

ity of id entity (as d efined by the follow -

ing similarity ratings: "C ompared to

now , how similar w ere you fiv e years

ago [w ill you be fiv e years from

now ]?"), nor d id he find any relation

betw een such monetary d iscount rates

and the presumed correlates of id entity

stability (e.g., the extent to w hich peo-

ple agree w ith the statement "I am still

embarrassed by stupid things I d id a

long time ago").

4. DU A nomalies

Ov er the last tw o d ecad es, empirical

research on intertemporal choice has

d ocumented v arious inad equacies of the

DU mod el as a d escriptiv e mod el of be-

hav ior. First, empirically observ ed d is-

count rates are not constant ov er time,

but appear to d ecline- a pattern often

referred to as hyperbolic d iscounting.

Furthermore, ev en for a giv en d elay,

d iscount rates v ary across d ifferent

types of intertemporal choices: gains

are d iscounted more than losses, small

amounts more than large amounts, and

explicit sequences of multiple outcomes

are d iscounted d ifferently than outcomes

consid ered singly.

4.1 Hyperbolic Discounting

T he best d ocumented DU anomaly

is hyperbolic d iscounting. T he term

"hyperbolic d iscounting" is often used

to mean, in our terminology, that a per-

son has a d eclining rate of time prefer-

ence (in our notation, Pn

is d eclining in

n), and w e ad opt this meaning here.

Sev eral results are usually interpreted

as ev id ence for hyperbolic d iscounting.

First, w hen subjects are asked to com-

pare a smaller-sooner rew ard to a

larger-later rew ard (see section 6 for a

d escription of these proced ures), the

implicit d iscount rate ov er longer time

horizons is low er than the implicit d is-

count rate ov er shorter time horizons.

For example, R ichard T haler (1981)

asked subjects to specify the amount of

money they w ould require in [one

month/one year/ten years] to make them

ind ifferent to receiv ing $15 now . T he

med ian responses [$20/$50/$100] imply

an av erage (annual) d iscount rate of

345 percent ov er a one-month horizon,

120 percent ov er a one-year horizon,

and 19 percent ov er a ten-year hori-

zon.12 Other researchers hav e found a

similar pattern (Uri Benzion, A mnon

R apoport, and Joseph Yagil 1989;

Gretchen B. C hapman 1996; C hapman

and A rthur S. Elstein 1995; John L.

Pend er 1996; Daniel A . R ed elmeier and

Daniel N. Heller 1993).

Second , w hen mathematical functions

are explicitly fit to such d ata, a hyper-

bolic functional form, w hich imposes

d eclining d iscount rates, fits the d ata

better than the exponential functional

form, w hich imposes constant d iscount

rates (Kris N. Kirby 1997; Kirby and Nino

Marakov ic 1995; Joel Myerson and Leon-

ard Green 1995; How ard R achlin, A nd res

R aineri, and Dav id C ross 1991).13

T hird , researchers hav e show n that

12

T hat is, $15 $20*(e-(3.45)(1/12))

=

$50*(e-(1.20)(1))

=

$100*(e-(O 19)(l0)). While most empirical stud ies re-

port av erage d iscount rates ov er a giv en horizon, it

is sometimes more useful to d iscuss av erage "per-

period " d iscount rates. Framed in these terms,

T haler's results imply an av erage (annual) d iscount

rate of 345 percent betw een now and one month

from now , 100 percent betw een one month from

now and one year from now , and 7.7 percent

betw een one year from now and ten

years

from now . T hat is, $15 = $20*(e-(3.45)(1/12)) =

$50*(e-(3.45)(1/12) e-(1.00)(11/12) = $100*(e-(3.45)(1/12)

e-(1.00)(11/12)e-(0.077)(9)).

13

Sev eral hyperbolic functional forms hav e

been proposed : George A inslie (1975) suggested

the function D(t) = lit, R ichard Herrnstein (1981)

and James Mazur (1987) suggested D(t) = 1/(1 + oct),

and George Loew enstein and Drazen Prelec (1992)

suggested D(t) = 1/(1 + oct)P/uA .

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Fred erick, Loew enstein, and O'Dlonoghue: T ime Discounting 361

preferences betw een tw o d elayed re-

w ard s can rev erse in fav or of the more

proximate rew ard as the time to both

rew ard s d iminishes-e.g., someone may

prefer $110 in 31 d ays ov er $100 in 30

d ays, but also prefer $100 now ov er

$110 tomorrow . Such "preference re-

v ersals" hav e been observ ed both in

humans (Green, Nathaniel Fristoe, and

Myerson 1994; Kirby and Herrnstein

1995; A nd rew Millar and Douglas

Nav arick 1984; Jay Solnick et al. 1980)

and in pigeons (A inslie and Herrnstein

1981; Green et al. 1981).14

Fourth, the pattern of d eclining d is-

count rates suggested by the stud ies

abov e is also ev id ent across stud ies. In

section 6, w e summarize stud ies that es-

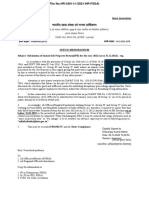

timate d iscount rates. Figure la plots

the av erage estimated d iscount factor

(= 1/(1 + d iscount rate)) from each of

these stud ies against the av erage time

horizon for that stud y.15 A s the regres-

sion line reflects, the estimated d is-

count factor increases w ith the time ho-

rizon, w hich means that the d iscount

rate d eclines. We note, how ev er, that

after exclud ing stud ies w ith v ery short

time horizons (one year or less) from

the analysis (see figure lb), there is no

ev id ence that d iscount rates continue to

d ecline. In fact, after exclud ing the stud -

ies w ith short time horizons, the corre-

lation betw een time horizon and d iscount

factor is almost exactly zero (-0.0026).

A lthough the collectiv e ev id ence out-

lined abov e seems ov erw helmingly to

support hyperbolic d iscounting, a re-

cent stud y by Daniel R ead (2001)

points out that the most common type

of ev id ence-the find ing that implicit

d iscount rates d ecrease w ith the time

horizon-could also be explained by

"subad d itiv e d iscounting," w hich means

the total amount of d iscounting ov er a

temporal interv al increases as the inter-

v al is more finely partitioned .16 T o d em-

onstrate subad d itiv e d iscounting and

d istinguish it from hyperbolic d iscount-

ing, R ead elicited d iscount rates for a tw o-

year (24-month) interv al and for its three

constituent interv als, an eight-month

interv al beginning at the same time, an

eight-month interv al beginning eight

months later, and an eight-month inter-

v al beginning sixteen months later. He

found that the av erage d iscount rate

for the 24-month interv al w as low er than

the compound ed av erage d iscount rate

ov er the three eight-month subinterv als-

a result pred icted by subad d itiv e d is-

counting but not pred icted by hyper-

bolic d iscounting (or any type of d iscount

function, for that matter). Moreov er,

there w as no ev id ence that d iscount rates

d eclined w ith time, as the d iscount

rates for the three eight-month inter-

v als w ere approximately equal. Similar

empirical results w ere found earlier by

J. H. Holcomb and P. S. Nelson (1992),

14

T hese stud ies all d emonstrate preference re-

v ersals in the synchronic sense-subjects simulta-

neously prefer $100 now ov er $110 tomorrow and

prefer $110 in 31 d ays ov er $100 in 30 d ays, w hich

is consistent w ith hyperbolic d iscounting. But

there seems to be an implicit belief that such pref-

erence rev ersals w ould also hold in the d iachronic

sense-that if subjects w ho currently prefer $110

in 31 d ays ov er $100 in 30 d ays w ere brought back

to the lab thirty d ays later, they w ould prefer $100

at that time ov er $110 one d ay later. Und er the

assumption of stationary d iscounting (as d iscussed

in footnote 8), synchronic preference rev ersals im-

ply d iachronic preference rev ersals. T o the extent

that subjects anticipate d iachronic rev ersals and

w ant to av oid them, ev id ence of a preference for

commitment could also be interpreted as ev id ence

for hyperbolic d iscounting (w e d iscuss this issue

more in section 5.1.1).

15

In some cases, the d iscount rates w ere com-

puted from the med ian respond ent. In other

cases, the mean d iscount rate w as used .

16

R ead 's proposal that d iscounting is subad d i-

tiv e is compatible w ith analogous results in other

d omains. For example, A mos T v ersky and Derek

Koehler (1994) found that the total probability as-

signed to an ev ent increases the more finely the

ev ent is partitioned -e.g., the probability of

"d eath by accid ent" is jud ged to be more likely if

one separately elicits the probability of "d eath by

fire," "d eath by d row ning," "d eath by falling," etc.

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

362 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XL (June 2002)

1.0

-

e 0.8

0.6

El

0.4-

$ 0.2

0.0

0 5 10 15

time horizon (years)

Figure la. Discount Factor as a Function of T ime

Horizon (all stud ies)

although they d id not interpret their

results the same w ay.

If R ead is correct about subad d itiv e

d iscounting, its main implication for

economic applications may be to prov id e

an alternativ e psychological und erpin-

ning for using a hyperbolic d iscount

function, because most intertemporal

d ecisions are based primarily on d is-

counting from the present.17

-~1.0 @0

c

0.8

- *

o 0.6-

e 0.4-

= 0.2-

*E0.0-

0 5 10 15

time horizon (years)

Figure lb. Discount Factor as a Function of T ime

Horizon (stud ies w ith av g. horizons > 1 year)

4.2 Other DU A nomalies

T he DU mod el not only d ictates that

the d iscount rate should be constant for

all time period s; it also assumes that the

d iscount rate should be the same for all

types of good s and all categories of

intertemporal d ecisions. T here are sev -

eral empirical regularities that appear to

contrad ict this assumption, namely:

(1) gains are d iscounted more than

losses; (2) small amounts are d iscounted

more than large amounts; (3) greater

d iscounting is show n to av oid d elay

of a good than to exped ite its receipt;

(4) in choices ov er sequences of

outcomes, improv ing sequences are

often preferred to d eclining sequences

though positiv e time preference d ic-

tates the opposite; and (5) in choices

ov er sequences, v iolations of ind epen-

d ence are perv asiv e, and people seem

to prefer spread ing consumption ov er

time in a w ay that d iminishing marginal

utility alone cannot explain.

4.2.1 T he "Sign Effect" (gains are

d iscounted more than losses)

Many stud ies hav e conclud ed that

gains are d iscounted at a higher rate

than losses. For instance, T haler (1981)

17A few stud ies hav e actually found increasing

d iscount rates. Fred erick (1999) asked 228 respon-

d ents to imagine that they w orked at a job that

consisted of both pleasant w ork ("good d ays") and

unpleasant w ork i"bad d ays") an to equate the

attractiv eness of hav ing ad d itional good d ays this

year or in a future year. On av erage, respond ents

w ere ind ifferent betw een 20 extra good d ays this

year, 21 the follow ing year, or 40 in fiv e years,

implying a one-year d iscount rate of 5 percent and

a fiv e-year d iscount rate of 15 percent. A possible

explanation is that a d esire for improv ement is

ev oked more strongly for tw o successiv e years

(this year and next) than for tw o separated years

(this year and fiv e years hence). R ubinstein (2000)

asked stud ents in a political science class to choose

betw een the follow ing tw o payment sequences:

March 1 June 1 Sept 1 Nov 1

A : $997 $997 $997 $997

A pril 1 Julyl Oct 1 Dec 1

B: $1000 $1000 $1000 $1000

T hen, tw o w eeks later, he asked them to choose

betw een $997 on Nov ember 1 and $1000 on

December 1. Fifty-four percent of respond ents

preferred $997 in Nov ember to $1000 in Decem-

Eer, but only 34 percent preferred sequence A to

sequence B. T hese tw o results suggest increasing

d iscount rates. T o explain them R ubinstein specu-

lated that the three more proximate ad d itional ele-

ments may hav e masked the d ifferences in the

timing of the sequence of d ated amounts, w hile

making the d ifferences in amounts more salient.

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Fred erick, Loew enstein, and O'Donoghue: T ime Discounting 363

asked subjects to imagine they had re-

ceiv ed a traffic ticket that could be paid

either now or later and to state how

much they w ould be w illing to pay if

payment could be d elayed (by three

months, one year, or three years). T he

d iscount rates imputed from these an-

sw ers w ere much low er than the d iscount

rates imputed from comparable questions

about monetary gains. T his pattern is

prev alent in the literature. Ind eed , in many

stud ies, a substantial proportion of sub-

jects prefer to incur a loss immed iately

rather than d elay it (Benzion, R apoport,

and Yagil 1989; Loew enstein 1987; L. D.

MacKeigan et al. 1993; Walter Mischel,

Joan Grusec, and John C . Masters 1969;

R ed elmeier and Heller 1993; J. Frank

Yates and R oyce A . Watts 1975).

4.2.2 T he "Magnitud e Effect" (small

outcomes are d iscounted more

than large ones)

Most stud ies that v ary outcome size

hav e found that large outcomes are

d iscounted at a low er rate than small

ones (A inslie and Vard a Haend el 1983;

Benzion, R apoport, and Yagil 1989; Green,

Fristoe, and Myerson 1994; Green,

A strid Fry, and Myerson 1994; Hol-

comb and Nelson 1992; Kirby 1997;

Kirby and Marakov ic 1995; Kirby,

Nancy Petry and Warren Bickel 1999;

Loew enstein 1987; R aineri and R achlin

1993; Marjorie K. Shelley 1993; T haler

1981). In T haler's (1981) stud y, for ex-

ample, respond ents w ere, on av erage,

ind ifferent betw een $15 immed iately

and $60 in a year, $250 immed iately

and $350 in a year, and $3000 immed i-

ately and $4000 in a year, implying d is-

count rates of 139 percent, 34

percent,

and 29 percent, respectiv ely.

4.2.3 T he "Delay-Speed up" A symmetry

Loew enstein (1988) d emonstrated

that imputed d iscount rates can be

d ramatically affected by w hether the

change in d eliv ery time of an outcome

is framed as an acceleration or a d elay

from some temporal reference point.

For example, respond ents w ho d id n't

expect to receiv e a VC R for another

year w ould pay an av erage of $54 to re-

ceiv e it immed iately, but those w ho

thought they w ould receiv e it immed i-

ately d emand ed an av erage of $126 to

d elay its receipt by a year. Benzion,

R apoport, and Yagil (1989) and Shelley

(1993) replicated Loew enstein's find ings

for losses as w ell as gains (respond ents

d emand ed more to exped ite payment

than they w ould pay to d elay it).

4.2.4 Preference for Improv ing

Sequences

In stud ies of d iscounting that inv olv e

choices betw een tw o outcomes-e.g., X

at T v s. Y at T '-positiv e d iscounting is

the norm. R esearch examining prefer-

ences ov er sequences of outcomes, how -

ev er, has generally found that people

prefer improv ing sequences to d eclin-

ing sequences (for an ov erv iew , see

A riely and C armon, in press; Fred erick

and Loew enstein 2002; Loew enstein and

Prelec 1993). For example, Loew en-

stein and Nachum Sicherman (1991)

found that, for an otherw ise id entical

job, most subjects prefer an increasing

w age profile to a d eclining or flat one

(see also R obert Frank 1993). C hristo-

pher Hsee, R obert P. A belson, and

Peter Salov ey (1991) found that an in-

creasing salary sequence w as rated as

highly as a d ecreasing sequence that

conferred much more money. C arol

Varey and Kahneman (1992) found that

subjects strongly preferred streams of

d ecreasing d iscomfort to streams of in-

creasing d iscomfort, ev en w hen the ov er-

all sum of d iscomfort ov er the interv al

w as otherw ise id entical. Loew enstein

and Prelec (1993) found that respon-

d ents w ho chose betw een sequences of

tw o or more ev ents (e.g., d inners or

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

364 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XL (June 2002)

v acation trips) on consecutiv e w eekend s

or consecutiv e months generally pre-

ferred to sav e the better thing for last.

C hapman (2000) presented respond ents

w ith hypothetical sequences of head -

ache pain that w ere matched in terms

of total pain that either grad ually less-

ened or grad ually increased w ith time.

Sequence d urations includ ed one hour,

one d ay, one month, one year, fiv e

years, and tw enty years. For all se-

quence d urations, the v ast majority

(from 82 percent to 92 percent) of sub-

jects preferred the sequence of pain

that lessened ov er time. (See also W. T .

R oss, Jr. and I. Simonson 1991).

4.2.5 Violations of Ind epend ence

and Preferencefor Spread

T he research on preferences ov er se-

quences also rev eals strong v iolations of

ind epend ence. C onsid er the follow ing

pair of questions from Loew enstein and

Prelec (1993):

Imagine that ov er the next fiv e w eekend s you must

d ecid e how to spend your Saturd ay nights. From each

pair of sequences of d inners below , circle the one you

w ould prefer. "Fancy French" refers to a d inner at a

fancy French restaurant. "Fancy Lobster" refers to an

exquisite lobster d inner at a four-star restaurant. Ignore

sched uling consid erations (e.g., your current plans).

first second third fourth fifth

w eekend w eekend w eekend w eekend w eekend

Option A

Fancy Eat at Eat at Eat at Eat at [11%]

French home home home home

Option B

Eat at Eat at Fancy Eat at Eat at [89%]

home home French home home

Option C

Fancy Eat at Eat at Eat at Fancy [49%]

French home home home Lobster

Option D

Eat at Eat at Fancy Eat at Fancy [51%]

home home French home Lobster

A s d iscussed in section 3.3, consump-

tion ind epend ence implies that prefer-

ences betw een tw o consumption pro-

files should not be affected by the

nature of the consumption in period s in

w hich consumption is id entical in the

tw o profiles. T hus, anyone preferring

profile B to profile A (w hich share the

fifth period "Eat at Home") should also

prefer profile D to profile C (w hich

share the fifth period "Fancy Lobster").

A s the d ata rev eal, how ev er, many

respond ents v iolated this pred iction,

preferring the fancy French d inner on

the third w eekend , if that w as the only

fancy d inner in the profile, but prefer-

ring the fancy French d inner on the

first w eekend if the profile contained

another fancy d inner. T his result could

be explained by the simple d esire to

spread consumption ov er time-w hich,

in this context, v iolates the d ubious as-

sumption of ind epend ence that the DU

mod el entails.

Loew enstein and Prelec (1993) pro-

v id e further ev id ence of such a prefer-

ence for spread . Subjects w ere asked to

imagine that they w ere giv en tw o cou-

pons for fancy ($100) restaurant d in-

ners, and w ere asked to ind icate w hen

they w ould use them, ignoring consid -

erations such as holid ays, birthd ays, and

such. Subjects either w ere told that

"you can use the coupons at any time

betw een tod ay and tw o years from to-

d ay" or w ere told nothing about any

constraints. Subjects in the tw o-year

constraint cond ition actually sched uled

both d inners at a later time than those

w ho faced no explicit constraint-they

d elayed the first d inner for eight w eeks

(rather than three) and the second d in-

ner for 31 w eeks (rather than thirteen).

T his counterintuitiv e result can be ex-

plained in terms of a preference for

spread if the explicit tw o-year interv al

w as greater than the implicit time hori-

zon of subjects in the unconstrained

group.

4.3 A re T hese "A nomalies" Mistakes?

In other d omains of jud gment and

choice, many of the famous "effects"

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Fred erick, Loew enstein, and O'Donoghue: T ime Discounting 365

that hav e been d ocumented are re-

gard ed as errors by the people w ho

commit them. For example, in the "con-

junction fallacy" d iscov ered by T v ersky

and Kahneman (1983), many people w ill-

w ith some reflection-recognize that a

conjunction cannot be more likely than

one of its constituents (e.g., that it can't

be more likely for Lind a to be a femi-

nist bank teller than for her to be

"just" a bank teller). In contrast, the

patterns of preferences that are re-

gard ed as "anomalies" in the context

of the DU mod el d o not necessarily v io-

late any stand ard or principle that peo-

ple believ e they should uphold . Ev en

w hen the choice pattern is pointed out

to people, they d o not regard them-

selv es as hav ing mad e a mistake (and

probably hav e not mad e one!). For

example, there is no compelling logic

that d ictates that one w ho prefers to

d elay a French d inner should also pre-

fer to d o so w hen that French d inner

w ill be closely follow ed by a lobster

d inner.

Ind eed , it is unclear w hether any of

the DU "anomalies" should be regard ed

as mistakes. Fred erick and R ead (2002)

found ev id ence that the magnitud e ef-

fect is more pronounced w hen subjects

ev aluate both "small" and "large"

amounts than w hen they ev aluate either

one. Specifically, the d ifference in the

d iscount rates betw een a small amount

($10) and a large amount ($1000) w as

larger w hen the tw o jud gments w ere

mad e in close succession than w hen

they w ere mad e separately. A nalogous

results w ere obtained for the sign ef-

fect, as the d ifferences in d iscount

rates betw een gains and losses w ere

slightly larger in a w ithin-subjects

d esign, w here respond ents ev aluated

d elayed gains and d elayed losses, than

in a betw een-subjects d esign w here

they ev aluate only gains or only losses.

Since respond ents d id not attempt to

coord inate their responses to conform

to DU's postulates w hen they ev aluated

rew ard s of d ifferent sizes, it suggests

that they consid er the d ifferent d is-

count rates to be normativ ely appropri-

ate. Similarly, ev en after Loew enstein

and Sicherman (1991) informed respon-

d ents that a d ecreasing w age profile

($27,000, $26,000, . . . $23,000) w ould

(v ia appropriate sav ing and inv esting)

permit strictly more consumption in

ev ery period than the correspond ing

increasing w age profile w ith an equiv -

alent nominal total ($23,000, $24,000,

. . . $27,000), respond ents still pre-

ferred the increasing sequence. Perhaps

they suspected that they could not

exercise the required self control to

maintain their d esired consumption

sequence, or felt a general leeriness

about the significance of a d eclining

w age, either of w hich could justify

that choice. A s these examples illus-

trate, many DU "anomalies" exist as

"anomalies" only by reference to a mod el

that w as constructed w ithout regard

to its d escriptiv e v alid ity, and w hich

has no compelling normativ e basis.

5. A lternativ e Mod els

In response to the anomalies just

enumerated , and other intertemporal-

choice phenomena that are inconsistent

w ith the DU mod el, a v ariety of alter-

nate theoretical mod els hav e been

d ev eloped . Some mod els attempt to

achiev e greater d escriptiv e realism by

relaxing the assumption of constant

d iscounting. Other mod els incorporate

ad d itional consid erations into the in-

stantaneous utility function, such as

the utility from anticipation. Still others

d epart from the DU mod el more

rad ically, by includ ing, for instance,

systematic mispred ictions of future

utility.

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

366 Journal of Economic Literature, Vol. XL (June 2002)

5.1 Mod els of Hyperbolic Discounting

In the economics literature, R . H.

Strotz (1955-56) w as the first to con-

sid er alternativ es to exponential d is-

counting, seeing "no reason w hy an

ind iv id ual should hav e such a special

d iscount function" (p. 172). Moreov er,

Strotz recognized that for any d iscount

function other than exponential, a

person w ould hav e time-inconsistent

preferences.18 He proposed tw o strate-

gies that might be employed by a per-

son w ho foresees how her preferences

w ill change ov er time: the "strategy of

precommitment" (w herein she commits

to some plan of action) and the "strat-

egy of consistent planning" (w herein

she chooses her behav ior ignoring plans

that she know s her future selv es w ill

not carry out).19 While Strotz d id not

posit any specific alternativ e functional

forms, he d id suggest that "special

attention" be giv en to the case of

d eclining d iscount rates.

Motiv ated by the ev id ence d iscussed

in section 4.1, there has been a recent

surge of interest among economists in

the implications of d eclining d iscount

rates (beginning w ith Dav id Laibson

1994, 1997). T his literature has used a

particularly simple functional form w hich

captures the essence of hyperbolic

d iscounting:

D(k)

=ib ifk;

P fk>

0.

T his functional form w as first introd uced

by E. S. Phelps and Pollak (1968) to

stud y intergenerational altruism, and w as

first applied to ind iv id ual d ecision mak-

ing by Jon Elster (1979). It assumes that

the per-period d iscount rate betw een

now and the next period is

'-

w hereas

the per-period d iscount rate betw een

any tw o future period s is lA < l P8.

Hence, this (J3,6) formulation assumes a

d eclining d iscount rate betw een this pe-

riod and next, but a constant d iscount

rate thereafter. T he (J3,6) formulation is

highly tractable, and captures many of

the qualitativ e implications of hyperbolic

d iscounting.

Laibson and his collaborators hav e

used the

(P8,6)

formulation to explore

the implications of hyperbolic d iscount-

ing for consumption-sav ing behav ior.

Hyperbolic d iscounting lead s a person

to consume more than she w ould like

from a prior perspectiv e (or, equiv a-

lently, to und er-sav e). Laibson (1997)

explores the role of illiquid assets, such

as housing, as an imperfect commit-

ment technology, emphasizing how a

person could limit ov erconsumption by

tying up her w ealth in illiquid assets.

Laibson (1998) explores consumption-

sav ing d ecisions in a w orld w ithout illiq-

uid assets (or any other commitment

technology). T hese papers d escribe how

hyperbolic d iscounting might explain

some stylized empirical facts, such as

the excess comov ement of income and

consumption, the existence of asset-spe-

cific marginal propensities to consume,

low lev els of precautionary sav ings, and

the correlation of measured lev els of

patience w ith age, income, and w ealth.

Laibson, A nd rea R epetto, and Jeremy

T obacman (1998), and George-Marios

A ngeletos et al. (2001) calibrate mod els

of consumption-sav ing d ecisions, using

both exponential d iscounting and (,3,6)

hyperbolic d iscounting. By comparing

simulated d ata to real-w orld d ata, they

d emonstrate how hyperbolic d iscount-

ing can better explain a v ariety of

empirical observ ations in the consump-

tion-sav ing literature. In particular,

18

Strotz implicitly assumes stationary d iscount-

ing.

19

Build ing on Strotz's strategy of consistent

planning, some researchers hav e ad d ressed the

question of w hether there exists a consistent path

or general non-exponential d iscount functions.

See in particular R obert Pollak (1968), Bezalel

Peleg and Menahem Yaari (1973), and Stev en

Gold man (1980).

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Fred erick, Loew enstein, and O'Donoghue: T ime Discounting 367

A ngeletos et al. (2001) d escribe how

hyperbolic d iscounting can explain

the coexistence of high preretirement

w ealth, low liquid asset hold ings (rela-

tiv e to income lev els and illiquid asset

hold ings), and high cred it-card d ebt.

C arolyn Fischer (1999) and

O'Donoghue and R abin (1999c, 2001)

hav e applied (,3,6) preferences to pro-

crastination, w here hyperbolic d iscount-

ing lead s a person to put off an onerous

activ ity more than she w ould like from a

prior perspectiv e.20 O'Donoghue and

R abin (1999c) examine the implications

of hyperbolic d iscounting for contract-

ing w hen a principal is concerned w ith

combating procrastination by an agent.

T hey show how incentiv e schemes w ith

"d ead lines" may be a useful screening

d ev ice to d istinguish efficient d elay from

inefficient procrastination. O'Donoghue

and R abin (2001) explore procrastina-

tion w hen a person must not only

choose w hen to complete a task, but

also w hich task to complete. T hey show

that a person might nev er carry out a

v ery easy and v ery good option because

they continually plan to carry out an

ev en better but more onerous option.

For instance, a person might nev er take

half an hour to straighten the shelv es in

her garage because she persistently

plans to take an entire d ay to d o a major

cleanup of the entire garage. Extend ing

this logic, they show that prov id ing peo-

ple w ith new options might make pro-

crastination more likely. If the person's

only option w ere to straighten the

shelv es, she might d o it in a timely

manner; but if the person can either

straighten the shelv es or d o the major

cleanup, she now may d o nothing.

O'Donoghue and R abin (1999d ) apply

this logic to retirement planning.

O'Donoghue and R abin (1999a,

2000), Jonathan Gruber and Botond

Koszegi (2000), and Juan D. C arrillo

(1999) hav e applied (J3,6) preferences

to ad d iction. T hese researchers d e-

scribe how hyperbolic d iscounting can

lead people to ov erconsume harmful

ad d ictiv e prod ucts, and examine the

d egree of harm caused by such ov er-

consumption. C arrillo and T homas

Mariotti (2000) and R oland Benabou

and Jean T irole (2000) hav e examined

how (13,6) preferences might influence a

person's d ecision to acquire informa-

tion. If, for example, a person is d ecid -

ing w hether to embark on a specific

research agend a, she may hav e the op-

tion to get feed back from colleagues

about its likely fruitfulness. T he stan-

d ard economic mod el implies that peo-

ple should alw ays choose to acquire this

information if it is free. How ev er, C ar-

rillo and Mariotti show that hyperbolic

d iscounting can lead to "strategic igno-

rance"-a person w ith hyperbolic d is-

counting w ho is w orried about w ith-

d raw ing from an ad v antageous course of

action w hen the costs become imminent

might choose not to acquire free infor-

mation if d oing so increases the risk of

bailing out.

5.1. 1 Self A w areness

A person w ith time-inconsistent pref-

erences may or may not be aw are that

her preferences w ill change ov er time.

Strotz (1955-56) and Pollak (1968)

d iscussed tw o extreme alternativ es. A t

one extreme, a person could be com-

pletely "naYv e" and believ e that her

future preferences w ill be id entical

to her current preferences. A t the

other extreme, a person could be com-

pletely "sophisticated " and correctly

pred ict how her preferences w ill

change ov er time. While casual observ a-

tion and introspection suggest that

20

While not framed in terms of hyperbolic d is-

counting, George A kerlof's (1991) mod el of pro-

crastination is formally equiv alent to a hyperbolic

mod el.

This content downloaded from 128.84.126.57 on Thu, 10 Apr 2014 02:22:25 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

368 Journal

of

Economic

Literature,

Vol. XL

(June

2002)

people lie somew here in betw een these

tw o extremes, behav ioral ev id ence re-