Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Films As Social History

Films As Social History

Uploaded by

Kakon AnmonaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Films As Social History

Films As Social History

Uploaded by

Kakon AnmonaCopyright:

Available Formats

e Heritage Journal, vol. 2, no. 1 (2005): pp.

1z1

Films as Social Histoiy

P. Ramlees Seniman Bujang Lapok

and Malays in Singapoie

(1950s60s)

by Syed Muhd Khaiiudin Aljunied

Depaitment of Malay Studies,

National Univeisity of Singapoie

is paper provides a critical reading and examination of P. Ramlees

flm, Seniman Bujang Lapok. Central to its argument is the appropriation

of such a flm as historical sources for the study of Malay society in the

1950s60s Singapore. By contextualising P. Ramlees portrayal of Malay

society within several key developments in his life and era, the article

propounds some major themes that refect the challenges and anxieties

faced by Malays then. It is hoped that this article will induce scholars

towards a rigorous interrogation of Malay flms which are currently at the

margins of Singapores historiography.

Introduction

D

espite theii sheei impoitance in poitiaying the social conditions

of Malays in post-Woild Wai II Singapoie, Malay flms of the

1950s and 1960s aie still in the maigins of what is peiceived as othei

impoitant histoiical souices at that time. As Anthony Milnei has

obseived, such negation is a pioduct of the methods and souices

Syed Muhd Khaiiudin Aljunied has completed his M.A. at the Depaitment of

Histoiy, National Univeisity of Singapoie and will be puisuing his PhD at the

School of Oiiental and Afiican Studies (S.O.A.S) at London. He was awaided the

Wong Lin Ken Medal foi Best Tesis (Histoiy) in 2001 and is cuiiently a Teaching

Staf at the Malay Studies Depaitment, teaching modules on Malay Cultuie and

Society. He was pieviously woiking as a Geneial Education Omcei with the

Ministiy of Education, Singapoie.

z i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

that colonial aichive histoiians have adopted in the study of Malay

histoiy. Colonial iecoids weie (and still aie) iegaided as moie

ieliable at the expense of othei useful Malay-based souices. Indeed,

it has impacted the kinds of questions and peispectives of histoiians

of the Malay Woild.

1

In theii puisuit of lineai naiiatives wiitten fiom

vintage points of a selected few, such genie of histoiians have often

oveilooked alteinative souices, which could piovide an illuminating

insight into the social histoiy of the Malays. Foiemost amongst

souices which could give an intimate Malay peispective of theii own

conditions, as Timothy Bainaid foicefully aigues, is Malay flm, but

it iemains laigely untapped.

2

Malay flms pioduced in Singapoie of the 1950s and 1960s

coincided at a time, when the island was undeigoing iapid social,

political, ieligious and economic changes. Diiected towaids an

audience whose avenues of visual enteitainment weie faiily limited

in those days, Malay flms often ieected and, at the same time,

inuenced Malay consciousness in such a context. So potent was

the powei of such flms that till today, many of the movie lines

has now established itself as new additions within the coipus of

Malay metaphois!

3

Two flm companies, Cathay Keiis and Shaw

Biotheis Malay Film Pioductions, emeiged stiongly in the post-wai

flm industiy pioducing moie than two hundied and ffty flms in

meiely two decades. Featuiing actois and actiess fiom vaiied social

backgiounds, such flms diew thousands eveiy weekend to cinemas,

iegaidless of age and class. Judging fiom piesent day standaids, it

can be said that a laige numbei amongst such aitists became Idols

foi the young and old then. Most piominent amongst them was

Teuku Zakaiia bin Teuku Nyak Puteh oi moie populaily known,

as P. Ramlee (192973) who iemains fiesh in the minds of Malays

today as an enteitainei and also a teachei par excellence. He was a

sciiptwiitei, comedian, diamatist, musician (composei and singei)

as well as diiectoi, all manifested in a man who was conceined with

the state of Malays

4

duiing his time.

5

In view of his peivasive inuence within the Malay flm industiy,

this aiticle will ciitically examine one of P. Ramlees celebiated

comedies, Seniman Bujang Lapok (eiioneously known in English as

Te Nitwit Movie Stais) (1961).

6

Nominated foi Te Best Comedy

Film duiing the ninth Asian Film Festival in Tokyo, Seniman Bujang

z i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

Lapok naiiates the stoiy of thiee unmaiiied and impoveiished

men, Ramli, Aziz and Sudin, and theii anxieties, challenges as well

as iomance whilst iesiding in a ciowded iented house. Fiantically

in seaich of a piopei job, the thiee men attended an audition to be

movie stais. Aftei many hiccups and hilaiious unintended mistakes,

they weie subsequently employed by the Malay Film Pioductions.

It pioved to be a ciitical junctuie of theii lives. Howevei, theii

enthusiasm in memoiising the movie lines was inteiiupted by

vaiious dimculties. Foiemost amongst these weie the distuibances

caused by the neighbouis within theii iented house. Amongst such

distuibances weie deafening aiguments between two couples, a man

iepaiiing his spoilt motoicycle and an eccentiic musician piactising

his skills in playing the tiumpet. Tis was followed by the almost

impossible ambitions of the thiee men to fnd theii love mates and

be happily maiiied. Ramli was in love with a nuise, Salmah, who

was at the same time couited by a neighbouihood hooligan, Shaiif.

Te movie ieached its climax with the buining of the iented house

by Shaiif due solely to Salmahs iejection of his maiiiage pioposal.

Upon discoveiing Shaiif s ciime, Ramli confionted the foimei and

handed him to the villageis to be sent to the police station. Te stoiy

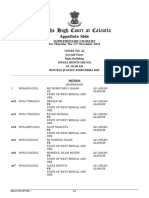

Bujang Lapok intioducing themselves to Kemat Hassan,

Diiectoi of Malay Film Pioductions.

i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

ends with each of the thiee men meeting theii loved ones to be

happily maiiied.

7

Te next pait of this papei will discuss two impoitant contexts

which shaped the pioduction of P. Ramlees flm Seniman Bujang

Lapok. Tis is followed by a discussion of vaiious majoi themes in

the movie which miiioied the vaiied challenges faced by the Malay

society in 1950s and 1960s Singapoie. Yet, the expositions that follow

aie but diops of an ocean of histoiical data that could be extiacted

fiom the movies and songs that have been pioduced by P. Ramlee, it

is hoped that such analytical discussions of Seniman Bujang Lapok

will convincingly put foith flms as useful histoiical souices foi the

study of Malays in Singapoie duiing the post-wai yeais.

Films and Contexts

Befoie engaging on an analysis of the flm, it is peitinent to state two

salient contexts that have inuenced its cieation and theiefoie would,

to a gieat extent, justify it as a useful histoiical souice. Te fist

would be the backgiound of the cieatoi oi pioducei of such flms.

Many, if not all, of P. Ramlees biogiapheis aie in consensus that his

woiks weie, in many ways, pioducts of his peisonal life expeiiences.

Wan Hamzah Awang, a ienowned Malaysian flm ciitic, went as fai

to asseit that P. Ramlee songs and flms had nevei depaited fiom

iealities of his peisonal life and milieu. Even when his flms enteied

into the iealm of fantasy, he was, in fact, indiiectly poitiaying

to his audiences the iealities of life in which he was an oiganic

pait.

8

Although only handful amongst P. Ramlees biogiapheis aie

piofessional histoiians and thus lacking of histoiical piofundity, a

cuisoiy glance at impoitant moments in P. Ramlees life does indeed

attests to such line of ieasoning.

P. Ramlee was boin on 22 Maich 1929 in Penang and giew up

at a time when Malaya was undeigoing the stiesses of the Gieat

Depiession. His fathei was an odd job labouiei and, piedictably, the

household was plagued by poveity and ill-health. As the only son

thiough his motheis second maiiiage, P. Ramlee had fond yet painful

memoiies of his eaily yeais. He sought to poitiay this piedicament

in the flm Ibu (Mothei) (1953) which naiiates the unceasing love

i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

between a child and his mothei. Such autobiogiaphical exposition of

his life was fuithei depicted in his fist successful flm, Penarek Beca

(Te Tiishaw Diivei) (1955). Te intended messages of class divisions

and poveity within the Malay society duiing his time was featuied so

efectively in the flm that it won seveial piestigious awaids.

9

Similai to most Malays in Penang of the 1930s, P. Ramlee giew

up leaining the iudimentaiy aspects of Islam. In fact, he was known

amongst village youths foi his melodious iecital of the Quian and

cuiiosities in many aieas of Islamic knowledge. P. Ramlee was

howevei ciitical of what seemed to him as tiaditional inteipietations

of Islamic laws. In Semerah Padi (1956), P. Ramlee launched such

ciitiques thiough the stoiies of two couples who weie punished

seveiely foi adulteiy and foinication. Tat being said, the main

message of the flm was almost ciystal cleai to his audience: Malays

aie Muslims and should adheie stiongly to such a potent belief.

Indeed, accoiding to Yusnoi Ef, P. Ramlee was much inclined to

innei and mystical piactises, what is teimed as ilmu batin (esoteiic

knowledge) iathei than meie laws and iituals.

10

Moving on to his eaily life, as eaily as eight yeais old, P. Ramlee

had developed inteiests in singing and playing of seveial musical

instiuments. Some few yeais latei, he soon became well-known foi

P. Ramlee, taking up his new appointment

as Diiectoi.

6 i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i ;

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

his multiple talents and was iespected as a piofound musician in the

Penang Oichestia.

11

His fame soon attiacted the attention of B.S.

Rahjans, an Indian diiectoi fiom Shaw Biotheis flm pioduction.

Te meeting between the two men pioved to be the fist impoitant

milestone which contiibuted to P. Ramlees meteoiic iise in the

Singapoie flm industiy. At Jalan Ampas studio, P. Ramlee ieceived

the suppoit and encouiagement of piominent flm diiectois. Tis was

coupled by the excellent facilities and skilled technicians who helped

give the maximum efects needed foi eveiy flm P. Ramlee acted

in.

12

Having sung, taken up majoi ioles and won piestigious awaids

thiough seveial successful flms, P. Ramlee was soon appointed as

a Film Diiectoi in 1955. Eight moie flms weie pioduced via his

diiectoiship and by the time Seniman Bujang Lapok (1961) was

scieened in the cinemas, it almost became haid foi his fans to

difeientiate P. Ramlee, the actoi, and the man in ieal life. Te two

ioles seemed to have conated within a peison who was undeigoing

a piocess of self-discoveiy and ielentless commitment towaids social

iefoimation.

One of P. Ramlees cential conceins as ieected in the flms

pioduced in cosmopolitan Singapoie was the complexities of having

to maintain tiaditional Malay values whilst at the same time, keeping

up with the coming of modeinity. P. Ramlee believed in a symbiotic

ielationship of both elements in the daily lives of Malays duiing his

time. In his flms, P. Ramlee highlighted that Malays must adopt what

was best fiom theii coipus of inheiited values as well as Westein

modeinity. He felt that it was the iigid and extieme adheience

towaids Malay values that had biought about an unquestioning

loyalty towaids theii iuleis as well as also othei foims of social

pioblems. He poitiayed such ciiticisms in his flm Hang Tuah (1956),

which was based on a celebiated Malay classic. P. Ramlee ended the

movie with a depaituie fiom the classical Malay text by adding a

signifcant monologue of the victoi, Hang Tuah, whom aftei having

killed his fiiend, doubted whethei such absolute faithfulness towaids

an unjust iuleis oideis was tiuly an act of honoui. Fuitheimoie,

to P. Ramlee, a modein society should have within it iudiments of

moiality and social cohesion along with the adoption of scientifc

knowledge and technological advancement. Such issues weie subtly

6 i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i ;

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

infused in Seniman Bujang Lapok and will be elaboiated in the latei

pait of this essay.

Te second impoitant factoi to be consideied would be the

social context in which the flm has been pioduced. Tis is impoitant

because flms aie pioducts of the social attitudes and ideological

tiends of a ceitain peiiod and place.

13

Seniman Bujang Lapok was

flmed at a time, which coincided with the ieawakening of the Malays,

paiticulaily the liteiaiy elites.

14

A majoi event that induced Malays

in Singapoie into full-blown activism in the post-wai yeais was the

Malayan Union Scheme which was announced in Octobei 1945. Tis

scheme was intioduced by the Biitish with the hope of consolidating

theii hold on the Malay States. Singapoie was, howevei, excluded

fiom the pioposed set up.

15

Malays in the Peninsulai who weie

distuibed by such a pioposal saw the implementation of the Malayan

Union as an attempt to eiode the poweis of the Sultans and a dilution

of Malay special iights. Te United Malays National Oiganization

(UMNO) was thus iegisteied in 1946, campaigning foi an alteinative

set up known latei as the Fedeiation of Malaya. Singapoie was again

excluded due to the Peninsulai Malays conceins about Chinese

numeiical dominance on the island. Although some Malays in

Singapoie accepted such iationale of political sepaiation, many hoped

that they would soon be incoipoiated into the laigei mainland Malay

community wheie many of theii families and fiiends lived. To ensuie

that the iights of Malays in Singapoie weie also piotected, UMNO

decided upon the establishment of its bianch known as Singapoie

UMNO (SUMNO) in 1948.

16

Its inuence amongst the Malays

alongside the Kesatuan Melayu Singapuia (KMS) was to ieach its

peak in 1957. Gieatly afected by the Malayan Union episode, laige

numbeis of Malays in Singapoie became moie active in the public

spheie than evei befoie. Vaiious oiganizations which aiticulated a

plethoia of inteiests mushioomed in the cosmopolitan colony. Issues

of class divisions, identity, belonging, cultuie, ieligion and language

weie contested, leading to a iise of polemics and tensions between

vaiious ethnic gioups on the island.

17

Contiastingly, in the iealm

of eveiyday life, food shoitages, diseases, unemployment, vices and

violence came to a height. Malays who weie mainly lowly educated

and engaged in fshing, poultiy ieaiing and ciop industiies had to

absoib such evei-incieasing challenges in the post-wai eia.

8 i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i ,

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

Amidst such anxieties and challenges faced by Malays, on 6

August 1950, a gioup of piominent teacheis and jouinalists decided

upon the foimation of a dynamic and cieative movement, Angkatan

Sasterawan 50 (ASAS 50) (meaning the Liteiaiy Geneiation of 1950,

the acionym ASAS means basis). Diiven by the motto of Seni

Untuk Masyaiakat (Aits foi Society), the gioup championed seveial

foiceful aims amongst which weie: (1) to fiee Malay society fiom

those elements of its cultuie which was obstiucting oi negating the

puisuit of modeinity and piogiess, (2) to advance the intellectual

awaieness of the raayat (Malay masses) towaids the ideals of

social justice, piospeiity, peace and haimony, (3) to fostei Malay

nationalism and last but not least, to iefne and piomote the Malay

language as the lingua fianca of Malaya.

18

Most piominent amongst

the membeis of ASAS 50 weie Kamaludin Muhamad (Keiis Mas),

Usman Awang (Tongkat Waiant), Suiatman Maikasan, Masuii S. N.,

Abdul Ghani Hamid, Muhammad Aiif Ahmad (Mas) and Asiaf Haji

Wahab. Membeis of the ASAS 50 adopted the iealist mode of wiiting

novels, shoit stoiies and poems. Such style of wiiting was emphasised

upon by ideologues of ASAS 50 fiom time to time with the delibeiate

intent of going against pieceding genies, which to them, weie too

pieoccupied with stylistics and tiivial aspects of human life, hence

not ieecting the tiue sufeiing of the common people. It is woith

quoting Keiis Mas at length who succinctly desciibed the ASAS

50 at the peak of theii engagement with the context in which they

opeiated:

In the feld of literature, the proponents of ASAS 50 adopted

a new breathe of style, employing a mode of language that

is fresh, departing from the preceding genre of writers,

propounding the themes of societal awareness, politics and

culture with the aim of revitalizing the spirit of freedom,

the spirit of independence of a people (bangsa) of its own

unique sense of honour and identity, upholding justice and

combating oppression.

.

We criticised societal backwardness and those whom

8 i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i ,

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

we regard as the instruments responsible for the birth

of such backwardness. We criticised colonialism and its

instruments, that is, the elite class, those whose consciousness

have been frozen by the infuence of feudalism and myths,

and superstition that has been enmeshed with religion.

(translation mine)

19

Ramli and Aziz in a flm audition with a feice yet comical

Diiectoi, Ahmad Nisfu.

P. Ramlee was veiy much inuenced by such developments and

these ideals weie ieected in the flms he pioduced in Singapoie.

In fact, P. Ramlee was peisonally amliated with membeis of ASAS

50. His own flm magazine, Bintang (Stai), was edited by Fatimah

Muiad who was the wife of ASAS 50 ideologue, Asiaf. By the eaily

1960s, Asiaf was alieady a well-known wiitei and was iesponsible

foi infusing intellectual ideas of ASAS 50 into Bintang as well

as shaiing his thoughts with P. Ramlee.

20

As obseived by a flm

histoiian, paiallel to the objectives of ASAS 50, the Bujang Lapok

Seiies

21

weie comedies mengandungi sindiran-sindiran tajam

terhadap masyarakat (that has within it, shaip ciiticisms of the

society) at that time.

22

Tus, similai to the tiend of iealism in Malay

wiiting in the 1950s, male chaiacteis of Seniman Bujang Lapok weie

poitiayed as economically and socially downtiodden. Repiesenting

the piedicament of a laige segment of Malay men at that time, these

thiee comical fguies (Ramli, Sudin and Aziz) had left theii villages

to seek employment in the uiban aieas without any special skill oi

1o i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i 11

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

knowledge that would enable them to secuie luciative oi piestigious

occupations.

23

Fuitheimoie, in Seniman Bujang Lapok, the chaiacteis

weie given names that weie, in ieality, theii own. Accoiding to Aziz

Sattai (one of the Bujang Lapok), P. Ramlee had always wanted the

actois (himself included) duiing flming to be what they weie truly

like in ieal life. Tiough this, P. Ramlee hoped to highlight the tiue

feelings and conditions of the common people then.

24

Major emes of Seniman Bujang Lapok

Fiom the eailiei discussion, it is undeniable that the Seniman Bujang

Lapok as well as othei flms pioduced by P. Ramlee aie impoitant

souices of iefeience foi the social histoiy of the Malays. In this

section, instead of examining the flm as it unfolds diachionically

oi appioaching it fiom the peispective of its technical, aitistic and

linguistic sophistications, I will attempt to highlight some majoi

themes that weie piopounded thiough the flm that had functioned

as iepiesentations of the Malay society in the 1950s and 1960s

Singapoie. To avoid fiom falling into the fallacy of ieading too

much into the flm, I have included the fndings of seveial academic

studies and also insights fiom published memoiis by P. Ramlees

contempoiaiies which aie in line with the issues highlighted by him.

(a) After Efects of the Japanese Occupation

One of the majoi themes piopounded in the flm was the aftei efects

of the Japanese occupation. In this, P. Ramlee had biought to light

two poweiful efects. Te fist, socio-psychological in natuie, was the

phobia of bomb attacks. Tis was ieected in the chaiactei Sudin,

who had instantaneously, took covei undei the table of a cofee shop

when one of the tyies of a loiiy buist. When asked by Ramli on why

he had ieacted in such a way, Sudin ieplied that he iemembeied

the times when the Japanese had bombed the countiy. Ramli then

ieminded Sudin to foiget about such incidences and concentiate

upon theii efoits to look foi a decent job. Although tiivial to many,

this shoit scene piopounds the social psychology of the iuial Malays

1o i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i 11

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

then that had scaicely iecoveied fiom the shock of the Japanese

occupation. It is woithwhile to note that no academic studies have

so fai been undeitaken to examine in this aspect of Malay life in

Singapoie. Useful (yet pioblematic) souices that aie ieadily available

today consist of oial histoiy iecoids and memoiis by peisonalities

who witnessed and expeiienced the iavages of Japanese iule and its

subsequent impact. Nonetheless, in his iecently published memoii,

the ex-Ministei of Social Afaiis in Singapoie Pailiament, Mi Othman

Wok, iecounted how the Malay villages weie left laigely unscathed by

continuous Japanese bombings until late Januaiy 1942. Due to this,

theie giew a sense of complacency amongst those who felt that only

Biitish militaiy installations would be taigeted. But aftei witnessing

the devastation caused by such bombs, which iesulted in the deaths

of neighbouis and ielatives, ieality began to sink in and Malays then

iealized that they weie in a wai zone.

25

Such feais and memoiies

haunted the Malay psyche foi many yeais theieaftei.

Anothei efect of the wai that was highlighted thiough the

flm was the inteiiuption of education amongst the Malays. Duiing

the inteiview by Kemat Hassan, the Managei of the Malay Film

Pioductions, Ramli mentioned he had attended Malay school up

to Standaid Five and English school up to Standaid Foui and half!

When asked why theie is a half , Ramli explained that he was in

school when the Japanese attacked Malaya. Te iest of the Bujang

Lapok also ieected low levels of educational achievements. Indeed,

the Japanese Occupation had not only disiupted the education of the

Malays, but it has also woisened the alieady existing low levels of

paiticipation of the Malays in mainstieam schools.

26

In theii efoits

to gain the suppoit of the Malay community, the Japanese made it

compulsoiy foi all students to leain the Japanese language as well

as cultuie and negated the cuiiiculum that was implemented by

the Biitish colonialists. Accoiding to Said Zahaii who latei became

a ienowned Malay jouinalist in Utusan Melayu of the post-wai

yeais, Malays peiceived these new linguistic and cultuial policies

as acceptable foi they piovided employment oppoitunities within

the Japanese administiation. Yet such idealism was doomed fiom

the onset. Towaids the end of the wai, school attendance was on a

decline as many began to iealize that such education meiely seived

the motives of the Japanese conqueiois.

27

Upon the end of the

1z i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i 1

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

Occupation, most Malays had to iely on theii mediocie qualifcations

attained piioi to the Second Woild Wai. Te low level of education

amongst the Malays manifested itself in occupational patteins. In late

1950s, two-thiids of the Malay population weie engaged in menial

occupations such as gaideneis, omce boys and labouieis.

28

To stiess

upon his ciiticisms of the slumbei and foolishness of the Malays

in the iealm of education, P. Ramlee even iesoited to the usage of

deiogatoiy woids such as stupid (bodoh) and idiot (bahalol)

in many instances of the flm. Wittingly, he had highlighted such

seiious educational pioblems in a jokingly mannei foi his audiences

to discein.

(b) Malays and the Challenge of Modernity

Yet anothei majoi theme that is woith highlighting is the challenge

of modeinity that the Malay society was giappling with in the 1950s

and 1960s. P. Ramlee intended to highlight that theie was a need to

fnd a balance between the maintenance of Malay cultuial values and

the onslaught of modeinity. Tis, as said eailiei, was in haimony with

the mood of facing up to the challenge of modeinisation amongst

the Malay liteiaiy elites. Te Malay liteiaiy elites had engaged in the

wiiting of novels and plays that had centied on the theme that Malays

had abandoned theii tiaditional values and thus biought about moial

and spiiitual decay fiom within.

29

On the pieseivation of Malay values, P. Ramlee uses the

chaiactei of a Singh who woiks as a Jaga (watchman). Te Singh

gave shaip ciiticisms to Sudin foi his lacking in adab (ethics) and

foi not behaving in the ways of an orang Melayu (Malay). Ramli then

echoes the slogan of ASAS 50 by saying that Sudin was soiely lacking

of Malay ethics as ieected in the language. Bahasa menunjukkan

bangsa tau! (Language ieects the conditions of a community!),

Ramli exclaimed.

Te Singh went on to chide anothei man foi not ieecting

the spiiit of gotong royong (cohesiveness) in iesponse to the latteis

comments that the thiee men (Ramli, Sudin and Aziz) weie not

beftting to be flm stais. Te Singh iemaiked that Malays cannot

piogiess if cohesiveness which was pait of the Malay cultuie was

1z i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i 1

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

absent. Such emphasis on the spiiit of gotong royong was continuously

illustiated in the events that had taken place in the long house which

the Bujang Lapok iesided. Communal spiiit was highlighted in the

flm as a social contiol mechanism that could solve family disputes

and foi the community to infoim each othei of any catastiophe that

had befallen the occupants in the long house. In the conclusive pait

of the flm, the spiiit gotong royong was ieiteiated yet again in cleaiei

way when the villageis musteied each otheis couiage to collectively

aiiest, Shaiif, the notoiious neighbouihood hooligan.

Going fuithei, to highlight and piomote the meiits of

modeinity, P. Ramlee had used the example of the Post Omce in

safeguaiding money and piopeity. At the end of the flm, Salmah,

the wife-to-be of Ramli, assuied him that hei money had not been

buint to ashes as a iesult of the destiuction of theii long house.

Instead, she mentioned it was diselamatkan (savediunscathed)

because hei mothei had deposited the money in the Post Omce. P.

Ramlee was indiiectly appealing his Malay audiences to capitalise

on the advanced instiuments of modeinity and to iemove theii

bad habits of keeping money undei theii beds and pillows in the

attap-ioofed (palm-ioofed) houses that weie pione to fie! Tis was

also a delibeiate ie-enactment of a devastating fie that bioke out in

Singapoie at a village called Bukit Ho Swee on 25 May 1961, some

few months befoie Seniman Bujang Lapok weie scieened in the

cinemas. Foui people died, 85 weie injuied and 2,200 attap houses

weie destioyed. Sixteen thousand people became penniless paitly

due to the piactice of keeping money in theii homes.

30

(c) On the Understanding of Islam

Othei than that, P. Ramlee also biought to light the awed

undeistanding of Islam amongst Malays, of which he was ciitical.

Fiist was the issue of polygamy. In one of the scenes, a man was

caught by his wife dancing with anothei woman. Aftei a heated

veibal aigument, the man then pleaded innocence in the context of

Islam by stating that the woman was his second wife. Te fist wife

commented piofoundly that, Ooh! pasal nak berbini, ikut undang-

undang Islam ye! Pasal sembahyang, puasa kenapa tak nak ikut

1 i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i 1

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

undang-undang Islam! (Ooh, with iegaids to maiiiage, you follow

teachings of Islam!, [but] when it comes to piayeis and fasting, why

do you not follow Islam?). P. Ramlee, who was maiiied foi multiple

times, did not howevei nullify polygamy which he acknowledged as

an accepted element of the Islamic law. He uses the chaiactei Aziz

who admonished the man by saying that the pioblem was not with

the law but with implementation of that law. Justice and faiiness

must be upheld if a man so decides on a polygamous maiiiage.

In hei monogiaph on e Muslim Matrimonial Court in

Singapore based on hei feldwoik caiiied out in 1963, Judith

Djamoui obseived that kathis (Muslim judges) weie paiticulaily lax

in deteimining the maiiiage status of intended couples. Teie thus

aiose a high pievalence of uniepoited polygamous maiiiages. In

addition to that, divoice iates amongst Malays peaked to moie than

50 pei cent in 1957. Djamoui also noted that theie weie occasions

wheie Malay men weie found to have quietly kept anothei wife in

town oi in some othei pait of the Colony.

31

In 1958, the Shariah

Couit had been established and it was efective in ieducing divoice

iates and solving maiital disputes. Yet, cases of uniepoited maiiiages

weie still pievalent at the time when Seniman Bujang Lapok was

flmed.

32

Te next issue was on the belief in magical iocks and oinaments

to attain ceitain this-woildly objectives. Sudin had bought a magical

stone fiom Indian man which he had been assuied could make theii

managei lend Ramli thiee hundied and ffty dollais foi the latteis

wedding aiiangements. Yet, Sudin was only given fve dollais whilst

the stone that he had bought cost him ten dollais! In fiustiation,

Sudin mentioned that the stone was sial (an omen) iathei than a

souice of goodness and luck. He thiew it into a diain.

Such weie the satiies diiected by P. Ramlee towaids the Malay

society at that time. Hussein Alatas concuiied with this viewpoint

by aiguing that the Malays duiing the 1960s weie steeped in theii

beliefs of magic and mysticism in oidei to solve theii daily tiials and

tiibulations.

33

In an inuential academic tieatise, Syed Husin Ali

fuithei highlighted that the veision of Islam amongst the Malays

duiing this peiiod was peivaded by animistic beliefs. Malays weie

moie conceined with wasteful and pompous ceiemonies which weie

fai fiom the teachings of Islam. Moieovei, Islam amongst Malays was

1 i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i 1

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

essentially devoid of the iational and philosophical undeipinnings.

Malays weie also found to be paiticulaily lax in theii obseivances of

essential piecepts such as piayeis and fasting.

34

(d) Poverty (Kemiskinan)

Last but not least, anothei iecuiiing theme in P. Ramlees flm is

poveity. Malays weie poitiayed as an economically depiessed and

maiginal community who weie depiived of the basic essentials of

life such as food, health and lodging. Paiadoxically, in the midst of

such piedicament, Malays weie, at the same time, a close-knitted

community whose values of biotheihood and kinship weie still

intact and continuously piopagated. Te Bujang Lapok weie, in a

sense, iepiesentations of Malay poveity. In the eailiei paits of the

flm, Ramli had tiied to sell his piized possession which was a toin

undeigaiment to a Chinese iag-and-bone man. Te man iesponded

that such undesiiable item could make him faint, what moie to

be sold. Te flm went on to images of Ramli having placed two

biicks on a pillow in oidei to iion his pants. Being an integial pait

amongst those who lived below the poveity line then, the Bujang

Lapok could not even dieam of owning an iion. At anothei setting,

Sudin complained of the need foi him to stand on a long queue eveiy

moining due to the lack of toilets in the villages. In a comical way he

iemaiked, Heh apalah kita ni? Mau berak pun mau kena beratur!

Berapa lama mau tunggulah! (Heh what [life] aie we in? One has to

queue in oidei to ielieve ones bowels! How long must we wait?).

Having completed his feldwoik on the Malays in distiicts of

Geylang and Jalan Eunos, an Ameiican academic William Hanna

obseived that Malays in mid-1960s Singapoie weie by fai the most

undei-developed ethnic giouping in Singapoie. Te kampongs

(villages) which most Malays lived weie plaqued by diseases such

as malaiia and tubeiculosis. Infant moitality was high due to pooi

diainage systems, lack of health seivices and unclean watei. Yet,

with the iising piessuies by nationalists and politicians towaids

the goveinment minimalist policies, conditions began to impiove

towaids the second half of the 1960s, albeit, at a veiy slow iate.

Accoiding to Hanna, such developments within the Malay

16 i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i 1;

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

community piovided the backgiound and impetus foi the outbieak

of the 1964 iacial iiots.

35

Conclusion

Tioughout this essay, I have aigued that the flm Seniman Bujang

Lapok is indeed a useful histoiical souice foi the social histoiy of the

Malays in 1950s and 1960s Singapoie. I have biought to light some

majoi themes that have been piopounded by P. Ramlee in this flm.

Te aftei efects of the Japanese occupation, challenges of modeinity,

tensions in the undeistanding of Islam and poveity miiioied P.

Ramlees peisonal stiuggle as well as the challenges and anxieties

faced by Malays then. It is theiefoie not suipiising that these themes

weie oft-iepeated in most, if not, all of P. Ramlees pioductions. Most

impoitantly, the following naiiatives has demonstiated to us that

flms can be a useful addition alongside othei souices of social histoiy

such as oial iecoids, memoiis, newspapeis, coioneis iecoids and

goveinmental iepoits. Te essential task of a histoiian (and peihaps

anthiopologists as well as sociologists) is thus to tease out peisuasive

evidences fiom such flms, cioss-examining it with othei souices

and pioviding iational inteipietations of vaiied aspects of the Malay

society in a given peiiod. Such histoiy, like all histoiies, may not be

peifect, but it may help to open doois and piovoke questions foi latei

efoits.

In conclusion, it is peihaps peitinent to iestate that much has

been done to uncovei piecise details of the life of this extiaoidinaiy

man who is, an Intellectual in his own iight. Yet, extensive and

compiehensive ieseaich to demonstiate how the social histoiy of

Malays in Singapoie could be eniiched thiough the medium of flms

pioduced by P. Ramlee iemains a neglected topic amongst scholais

fiom vaiied disciplines. It is hoped that this papei has piovided the

impetus towaids analysing the hundieds of flms and songs pioduced

by the Seniman Agung (Gieat Aitiste)

36

in the light of theii histoiical

signifcance.

16 i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i 1;

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

NOTES

1.

A.C. Milnei, Colonial Recoids Histoiy: Biitish Malaya, Kajian Malaysia 4, 2

(1986): 118.

2. Timothy P. Bainaid, Chickens, Cakes and Kitchen: Food and Modeinity in

Malay Films of the 1950s and 1960s, in Reel Food: Essays on Food and Film,

ed. Anne L. Bowei (New Yoik: Routledge, 2004), pp. 767.

3.

Timothy P. Bainaid and Syed Muhd Khaiiudin Aljunied, Malays in

Singapoie: 13001959, in Malay Heritage in Singapore, ed. Aileen Lau

(Singapoie: Suntiee Media, 2006), foithcoming.

4. I am awaie of the ongoing debates on the defnition of Malay amongst

scholais of vaiied felds. Tania Li in hei book, Malays in Singapore: Culture,

Economy, and Ideology (Singapoie: Oxfoid Univeisity Piess, 1989) had

chosen to avoid such debates and get on with analysing the social gioup

that she defned as Malays. Judith Nagata in hei essay, What is A Malay?

highlighted the inheient pioblem of using Malay as a social categoiy in the

context of Malaysia and Singapoie due its uidity in day-to-day piactise. In

the context of this essay, I have employed the defnition given by Malaysian

constitution that is, Malay is one who is a Muslim, habitually speaks the

Malay language and follows the Malay custom oi adat.

5. Mahiiin Hassan, P. Ramlee A Son of Penang, Malaysia in History 22

(1979): 1.

6. Tan Sii P. Ramlee, Seniman Bujang Lapok (Selangoi: Common Voyage, 1961).

Te Nitwit Movie Stais is an inaccuiate tianslation of the movie title. Te

piopei Malay tianslation should be Te Downtiodden Unmaiiied Aitistes.

7. Foi a detailed desciiption of the flm, see Ahmad Saiji, P. Ramlee: Erti Yang

Sakti, (Kuala Lumpui: Pelanduk Publications, 1999), pp. 34952.

8. Wan Hamzah Awang, Manusia P. Ramle (Kuala Lumpui: Fajai Bakti, 1993),

p. 91.

9. Jan Uhde and Yvonne Ng Uhde, Latent Images: Film in Singapore (Singapoie:

Oxfoid Univeisity Piess, 2000), p. 13.

10. Yusnoi Ef, P. Ramlee Yang Saya Kenal (Selangoi: Pelanduk Publications,

2000), p. 42.

11. Ramlee Ismail, Kenangan Abadi P. Ramlee (Kuala Lumpui: Adhicipta, 1988),

pp. 413.

12. James Haiding and Ahmad Saiji, P. Ramlee: e Bright Star (Selangoi:

Pelanduk Publications, 2002), p. 233.

13. Richaid Dyei, Intioduction to Film studies, in John Hill and Pamela Chuich

Gibson, e Oxford Guide to Film Studies (New Yoik : Oxfoid Univeisity

Piess, 1998), p. 8.

14.

Tam, Seong Chee, Malays and Modernization: A Sociological Interpretation,

(Singapoie: Singapoie Univeisity Piess, 1983), p.216.

15. Dominions Omce to High Commissioneis, 21 Januaiy 1946, CO 537i1528.

Foi insights into the Malayan Union scheme and subsequent ieactions by

vaiious gioups in Malaya, see A.J. Stockwell, British Policy and Malay Politics

during the Malayan Union Experiment 19451948 (Singapoie: Malaysian

18 i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i 1,

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

Bianch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 1979), and Albeit Lau, e Malayan

Union Controversy 19421948 (Singapoie: Oxfoid Univeisity Piess, 1990).

16. Teie have debates on the oiigins of Singapoie UMNO. Some of its membeis

asseited that SUMNO was foimally established in 1952 yet existed as an

infoimal oiganization since the late 1940s. See foi example, Inteiviews with

Buang bin Junid on 1

Apiil, 1987, Oral History Records: Political Development

in Singapore 19451965, National Aichives of Singapoie.

17. Ungku Maimunah Mohd. Tahii, Modern Malay Literary Culture: A Historical

Perspective (Singapoie: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1987), pp. 33

42.

18. See ASAS 50, Memoranda Angkatan Sasterawan 50 (Kuala Lumpui: Oxfoid

Univeisity Piess, 1961).

19. Keiis Mas, 30 Tahun Sekitar Sastera (Kuala Lumpui: Dewan Bahasa dan

Pustaka, 1979), p. 131.

20. James Haiding and Ahmad Saiji, P. Ramlee, p. 103.

21. Te Bujang Lapok seiies weie:

(i) Bujang Lapok (1957)

(ii) Pendekai Bujang Lapok (1959)

(iii) Ali Baba Bujang Lapok (1961)

(iv) Seniman Bujang Lapok (1961)

22. Zakiah Hanum, Sepanjang Riwayatku (Kuala Lumpui: Utusan Publications,

1984), p.iii.

23. Tam, Seong Chee, Malays and Modernization, p. 216.

24. Wan Hamzah Awang, Manusia P. Ramlee, p. 75.

25. Othman Wok, Never in my Wildest Dreams (Singapoie: Singapoie National

Piinteis, 2000), pp. 534.

26. Ismail Kassim, Problems of Elite Cohesion: A Perspective from a Minority

Community (Singapoie: Singapoie Univeisity Piess, 1974), p. 36.

27. Said Zahaii, Dark Clouds At Dawn: A Political Memoir (Kuala Lumpui:

Insan, 2001), pp. 207.

28. Ismail Kassim, Problems of Elite Cohesion, p. 37.

29. A. M Tani, Pendahuluan, in A.M. Tani, Esei Sastera ASAS 50 (Kuala

Lumpui: Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, 1981), pp. xxiixxiii.

30. <http:iiwww.moe.gov.sgineisgstoiyibthosweefie.htm>. See also, Aichives

& Oial Histoiy Depaitment et al., Emergence of Bukit Ho Swee Estate : From

Desolation to Progress (Singapoie: Singapoie News & Publications Limited,

1983).

31. Judith Djamoui, Malay Kinship and Marriage in Singapore (New Yoik: Te

Athlone Piess, 1965), p. 83.

32. Judith Djamoui, e Muslim Matrimonial Court in Singapore (New Yoik: Te

Athlone Piess, 1966), pp. 2632.

33. Syed Hussein Alatas, Modernization and Social Change: Studies in

Modernization, Religion, Social Change and Development in South-East Asia

(Sydney: Angus & Robeitson, Sydney, 1972), p. 58.

34. Syed Husin Ali, e Malays: eir Problems and Future (Kuala Lumpui:

Heinemann Asia, 1981), p. 42.

18 i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i 1,

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

35. Willaid A. Hanna, e Malays Singapore (New Yoik: Ameiican Univeisities

Field Staf, 1966), Pait II, p. 10.

36. Abdullah Hussain, P. Ramlee : Kisah Hidup Seniman Agung (Petaling Jaya:

Pena, 1984).

REFERENCES

1. Unpublished Sources

Dominions Omce to High Commissioneis, 21 Januaiy 1946, CO 537i1528.

Inteiviews with Buang bin Junid on 1

Apiil, 1987, Oral History Records:

Political Development in Singapore 1945-1965, National Aichives of

Singapoie.

National Education Website:

< http:iiwww.moe.gov.sgineisgstoiyibthosweefie.htm>

2. Published Sources

Aichives & Oial Histoiy Depaitment et al., Emergence of Bukit Ho

Swee Estate: From Desolation to Progress. Singapoie: Singapoie News &

Publications Limited, 1983.

Abdullah Hussain, P. Ramlee: Kisah Hidup Seniman Agung. Petaling Jaya:

Pena, 1984.

Ahmad Saiji, P. Ramlee: Erti Yang Sakti. Kuala Lumpui: Pelanduk

Publications, 1999.

Alatas, Syed Hussein, Modernization and Social Change: Studies in

Modernization, Religion, Social Change and Development in South-East Asia.

Sydney: Angus & Robeitson, Sydney, 1972.

A.M. Tani, Esei Sastera ASAS 50. Kuala Lumpui: Dewan Bahasa dan

Pustaka, 1981.

ASAS 50, Memoranda Angkatan Sasterawan 50. Kuala Lumpui: Oxfoid

Univeisity Piess, 1961.

Bainaid, Timothy P., Chickens, Cakes and Kitchen: Food and Modeinity in

Malay Films of the 1950s and 1960s, in Reel Food: Essays on Food and Film,

ed. Anne L. Bowei. New Yoik: Routledge, 2004, pp. 7585.

zo i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i z1

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

Bainaid Timothy P. and Aljunied, Malays in Singapoie: 13001959, in

Malay Heritage in Singapore, ed. Aileen Lau. Singapoie: Suntiee Media,

2006, foithcoming.

Djamoui, Judith, Malay Kinship and Marriage in Singapore. New Yoik: Te

Athlone Piess, 1965.

________, e Muslim Matrimonial Court in Singapore. New Yoik: Te

Athlone Piess, 1966.

Haiding, James and Ahmad Saiji, P. Ramlee: e Bright Star. Selangoi:

Pelanduk Publications, 2002.

Dyei, Richaid, Intioduction to Film studies, in Hill, John and Gibson, Pamela

Chuich, e Oxford Guide to Film Studies. New Yoik: Oxfoid Univeisity

Piess, 1998, pp. 310.

Hanna, Willaid A., e Malays Singapore. New Yoik: Ameiican Univeisities

Field Staf, 1966.

Ismail Kassim, Problems of Elite Cohesion: A Perspective from a Minority

Community. Singapoie: Singapoie Univeisity Piess, 1974.

Lau, Albeit, e Malayan Union Controversy 19421948. Singapoie: Oxfoid

Univeisity Piess, 1990.

Li, Tania, Malays in Singapore: Culture, Economy, and Ideology. Singapoie:

Oxfoid Univeisity Piess, 1989.

Mahiiin Hassan, P. Ramlee A Son of Penang, Malaysia in History 22

(1979).

Milnei, A.C., Colonial Recoids Histoiy: Biitish Malaya, Kajian Malaysia 4,

2 (1986): 118.

Othman Wok, Never in my Wildest Dreams. Singapoie: Singapoie National

Piinteis, 2000.

Piince, Stephen R., Movies and Meaning: An Introduction to Film. Boston:

Allyn and Bacon, 1997.

Ramlee Ismail, Kenangan Abadi P. Ramlee. Kuala Lumpui: Adhicipta, 1988.

Said Zahaii, Dark Clouds At Dawn: A Political Memoir. Kuala Lumpui:

Insan, 2001.

zo i e Heritage Journal

Fiirs s Socii His:ovv

e Heritage Journal i z1

Svro Muno Knivuoi Aiiuiro

Stockwell, A.J., British Policy and Malay Politics during the Malayan Union

Experiment 19451948. Singapoie: Malaysian Bianch of the Royal Asiatic

Society, 1979.

Syed Husin Ali, e Malays: eir Problems and Future. Kuala Lumpui:

Heinemann Asia, 1981.

Tam, Seong Chee, Malays and Modernization: A Sociological Interpretation.

Singapoie: Singapoie Univeisity Piess, 1983.

Ungku Maimunah Mohd. Tahii, Modern Malay Literary Culture: A Historical

Perspective. Singapoie: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1987.

Wan Hamzah Awang, Manusia P. Ramlee. Kuala Lumpui: Fajai Bakti, 1993.

Yusnoi Ef, P. Ramlee Yang Saya Kenal. Selangoi: Pelanduk Publications,

2000.

Zakiah Hanum, Sepanjang Riwayatku. Kuala Lumpui: Utusan Publications,

1984.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Window To World History TG 6Document80 pagesWindow To World History TG 6hadiqa akbarNo ratings yet

- Christianity: ConclusionDocument3 pagesChristianity: ConclusionGeorgie AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Journey of The Soul (All Religions)Document6 pagesJourney of The Soul (All Religions)AnoushaNo ratings yet

- Ringkasan Eksekutif Arsitektur Keuangan Syariah Indonesia - English VersionDocument4 pagesRingkasan Eksekutif Arsitektur Keuangan Syariah Indonesia - English VersionMuhammad IsmailNo ratings yet

- The Rashidun CaliphateDocument3 pagesThe Rashidun CaliphateNikhin K.ANo ratings yet

- Coming To An Awareness of Language: The African-American FamilyDocument5 pagesComing To An Awareness of Language: The African-American FamilyBesT AppsNo ratings yet

- NTU Merit ListDocument2 pagesNTU Merit ListJamal ZafarNo ratings yet

- 12 Benefits of Feeding BirdsDocument5 pages12 Benefits of Feeding BirdsShahmeer KhanNo ratings yet

- Contoh Borang Permohonan KerjaDocument2 pagesContoh Borang Permohonan KerjaAnonymous bChWTIJtiANo ratings yet

- Tawba by Fazail PublisherDocument9 pagesTawba by Fazail PublisherislamanalysisNo ratings yet

- Misuse of Surah 12 Verse 106 by Salafis - Deleted Content.Document16 pagesMisuse of Surah 12 Verse 106 by Salafis - Deleted Content.Sheraz AliNo ratings yet

- DialogueDocument3 pagesDialoguekenshin uraharaNo ratings yet

- The Different Between Islamic Marketing and ConventionalDocument10 pagesThe Different Between Islamic Marketing and ConventionalAmeer Al-asyraf Muhamad100% (1)

- First Islamic Community - Prominent Personalities PDFDocument4 pagesFirst Islamic Community - Prominent Personalities PDFHaniya MahmoodNo ratings yet

- List To Manage StressDocument47 pagesList To Manage StressMohsin AbbasNo ratings yet

- D.B.M. Army Lists: BOOK 4: 1071 AD To 1500 ADDocument81 pagesD.B.M. Army Lists: BOOK 4: 1071 AD To 1500 ADAlessandro GalvaniNo ratings yet

- Discurso de Mustafa Kemal (1927)Document2 pagesDiscurso de Mustafa Kemal (1927)Francisco PeláezNo ratings yet

- F.4 180 2018 R 15 05 2019 DR PDFDocument1 pageF.4 180 2018 R 15 05 2019 DR PDFAnonymous QiU5hudNo ratings yet

- Cabinet of PakistanDocument5 pagesCabinet of PakistanshaniNo ratings yet

- 253-Article Text-2390-1-10-20230623Document20 pages253-Article Text-2390-1-10-20230623Syah juari lubis08No ratings yet

- Notice 7579 15 Dec 2022Document2 pagesNotice 7579 15 Dec 2022Debi Prasad SinhaNo ratings yet

- Principles of Islamic Capital MarketDocument6 pagesPrinciples of Islamic Capital MarketSyahrul EffendeeNo ratings yet

- Delhi SultanateDocument3 pagesDelhi Sultanatebookworm4uNo ratings yet

- Essay Writing: Aur Allah Jise Chahta Hai Izzat Deta Hai Aur Jise Chahta Hai Zillat Deta Hai. (Surah Imran)Document6 pagesEssay Writing: Aur Allah Jise Chahta Hai Izzat Deta Hai Aur Jise Chahta Hai Zillat Deta Hai. (Surah Imran)Shahid ImranNo ratings yet

- The 10 Adi Gurus: Sahaj YogaDocument22 pagesThe 10 Adi Gurus: Sahaj Yogadr_alisha100% (1)

- Data Kakak Damping & Maba SAAI 2018Document13 pagesData Kakak Damping & Maba SAAI 2018ItsRanggaNo ratings yet

- PRB 1Document126 pagesPRB 1Yulita Delfia Sari SagalaNo ratings yet

- Curse of HamDocument86 pagesCurse of HamSuhayl SalaamNo ratings yet

- The Ansaaru Allah CommunityDocument31 pagesThe Ansaaru Allah CommunityNicky KellyNo ratings yet

- SeerahDocument1,503 pagesSeerahSyed Mohammad Osama AhsanNo ratings yet