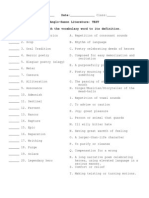

Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Notes For Critical Analysis

Notes For Critical Analysis

Uploaded by

Mona AlyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Notes For Critical Analysis

Notes For Critical Analysis

Uploaded by

Mona AlyCopyright:

Available Formats

Notes for Critical Analysis

These student papers are excellent though they are by no means perfect; they do have

flaws. The most common are awkward or unclear phrasing, faulty syntax, a contradiction

or a lapse in logic, faulty punctuation, and inconsistent use of verb tense. At the same

time, all the writers show intelligence, critical acumen, and an understanding of the novel

being analyzed. All the essays are persuasively argued, clearly written, and logically

organized. None merely paraphrases or summarizes the action; rather, they interpret the

action.

This said, would also like to point out that there are differences among them, for

instance, in the kind of topic chosen, the development of the idea, and the tone. Also,

some writers show greater intellectual sophistication, and some have greater mastery over

their prose.

!hen read student papers, am looking for

depth of insight into the novel,

independent thinking,

a well"organized, well reasoned, clearly written essay with almost no serious

errors.

am not looking for a particular interpretation#or my interpretation. $%ually successful

papers can be written to prove that &'( )rusoe*s conversion was heartfelt and profoundly

changed him and his life, &+( his conversion was superficial and he fell away once he left

the island, or &,( no definitive decision about the sincerity and depth of )rusoe*s

conversion is possible because -efoe is ambiguous about it.

have made three kinds of changes in transcribing the essays. corrected misspellings,

added missing words, and added punctuation if meaning was confusing. /therwise, the

text of the essays is reproduced exactly as written.

Technical Notes: have added illustrations, where appropriate.

Robinson Crusoe, Daniel Defoe

0obinson )rusoe""1True1 or 1)onvenient1 )onvert2

The writer defines his terms and thoroughly analyzes the topic.

1 )all 3im 4riday1. The $pitome of the 1Noble 5avage1 in Robinson Crusoe

The thesis that )rusoe6s relationship with 4riday is condescending,

$urocentric, and abusive is persuasively argued.

Clarissa, Samuel Richardson

The )haracter of 0obert 7ovelace

n exploring the nature and conse%uences of 7ovelace6s pride and drive to

power, this essay also analyzes his relationship with )larissa.

)larissa

The discussion of how 0ichardson handles )larissa6s private life in a public

way provides a sympathetic interpretation of )larissa and insight into

0ichardson6s moral values.

8en and nk

!riting letters is not merely a narrative techni%ue but reveals an essential

part of )larissa6s nature.

A Sicilian Romance, Ann Radcliffe

-eception and -isguise in A Sicilian Romance

The accumulation of detail makes, finally, the device of deception and

disguise the heart of the novel.

Non-Eighteenth-Century Novels

3uck6s 3ero 9ourney &:ark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn(

The writer applies 9oseph )ampbell6s definition of the hero to 3uck 4inn to

determine whether 3uck is a hero. 3er critical approach differs from that of the

preceding essays, which focus ;ust on the text of the novel.

The <erlocs at Their 4inal $ncounter &9oseph )onrad, The Secret Agent(

The writer focuses on a key scene, !innie <erloc6s murder of her husband,

as a way into the novel. =sing this scene, she is able to discuss the <erlocs6

characterization, their relationship, theme, symbolism, and mood.

Robinson Crusoe--True or Convenient Convert!

/ften, one finds oneself in a difficult situation. :any times, the situation ia entirely

caused by the individual, and therefore, easily understood. 3owever, situations often

arise that are not easily explainable. t is in these situations that many turn to religion for

answers. =sing religion to solve, or help solve problems, though, does not necessarily

entail a 1true conversion.1 /ftentimes, the individual becomes a transient or 1convenient

convert,1 whose faith lasts for the duration of the problem, and no longer. n -aniel

-efoe6s eighteenth century novel, Robinson Crusoe, )rusoe is faced with many problems.

These problems force )rusoe to look to >od for help. The reader is left to decide, though,

as to whether )rusoe undergoes a 1true1 religious conversioin or whether he simply

becomes 1conveniently religious.1

)rusoe makes his religious 1conversion1 while shipwrecked on a desolate island and

mired in the throes of an ague. =pon awakening from a sleep, )rusoe recollects and

reflects upon his past wicked life. )rusoe decides his detainment on the island is >od6s

punishment for his past foolish life in which he had 1not... the least sense ... of the fear

of >od in danger or of thankfulness to >od in deliverances.1 )rusoe then remembers his

father6s warning that if he embarked on his 1seaward ;ourneys1 >od would not bless

him. 0ealizing that he had re;ected >od6s counsel in his father6s advice, )rusoe says his

first prayer,17ord be my help, for am in great distress.1 This marks the beginning of

)rusoe6s religious life, in which he draws hope for, his deliverance from the island.

)rusoe6s faith in >od has a positive function in his life on the deserted island. 3e 4ound

hope in the words of >od, manifested in his ?ible. 1)all on me in the day of trouble, and

will deliver, and thou shalt glorify me,1 are the words of )rusoe1s inspiration. 3ope of

deliverance gives )rusoe a reason to live. nstead of despairing about his situation,

)rusoe, with the hope of eventual deliverance in the back of his mind, is able to make the

best of his situation on the island. 3e puts his energy to use, instead of gloating about his

situation, and he is able to 1furnish himself with many things1 by using raw materials an

the island. /n a deeper level, )rusoe6s faith in >od provided him with something even

more urgently needed than hope.

4aith in >od gave )rusoe a means through which to communicate his thoughts. >ranted,

>od is an abstract entity, but >od is an abstraction that re%uires belief or imagination, in

order to exist as an abstraction. Through the communication of ideas and hopes, coupled

with the mind power that was needed in order to conceptualize >od, )rusoe6s mind was

therefore kept active. >od kept )rusoe from insanity. !ithout >od, )rusoe6s loneliness

probably would have 1driven him over the edge.1 )rusoe6s faith in >od then, not only

provided him with hope for deliverance, but >od also functioned as an intangible

1something1 that functioned as a replacement for a tangible 1)ommunicator1 &person(.

)rusoe6s faith is dealt a severe blow, however, when 0obinson discovers a man6s

footprint on the beach of 1his1 island. 4ear raged through )rusoe6s mind at the sight of

the footprint. 3e wondered if the devil had contrived the image of a human6s foot in order

to scare him. Then, when reason sets in, )rusoe decides that the footprint must be the

remnant of a cannibal tribe6s visit to the island. 3e was terrified of the cannibals@ n wake

of this new found fear, )rusoe says.

..4ear banished all my religious hope, all that former confidence in >od, which was

founded upon such wonderful experience as had of 3is goodness, now vanished.

)rusoe6s faith seems to be 1paper thin1 here, and one must wonder about the validity of

his conversion. Then, however, )rusoe accepts the 1invasion1 of his island as ;ust

punishment from >od. )rusoe decides that 16twas my un%uestioned duty to resign

myself ...to 3is will; ... and my duty to hope...pray...and attend to the dictates...of 3is

providence.1

)rusoe6s resignation to the will of >od does not necessarily mean that he has truly

converted. 3is resignation could be interpreted as a final desperate effort to placate >od.

)rusoe certainly didn6t want to anger >od any more than he had already. :aybe )rusoe

saw the foot"print as a temptation to abandon his faith &he already intimated the workings

of the devil in creating the footprint(. Therefore,when he resigns himself to >od6s will,

)rusoe might be simply saying, 1>od, don6t want to anger you anymore, if you6re even

listening, and 6ll accept this as part of my fate.1 Also, by accepting the footprint, and the

possibility of 1foreign cannibalistic invasion,1 as a work of >od, and part of his fate,

)rusoe frees himself from having to take any action. /nce )rusoe resigns himself to

>od, he is happy, signifying a great load &worry, fear( having been lifted off his

shoulders.

The next time that )rusoe uses his moral reasoning is not long after he sights the

footprint on the beach. /ne day, )rusoe finds the beach littered with human bones,

obviously the remnants of a cannibal feast. )rusoe abhors this sight, forgets about the

cannibal6s presence as being >od6s punishment for him, and decides to put an end to the

cannibalistic feasting. 3e sets about making elaborate plans to murder some of the

cannibals, all of them if necessary. Then however, )rusoe decides that he has no

1authority ... to be ;udge and executioner1 of the savages. )rusoe reasons that the

cannibals had committed what he decided were crimes for so long and had gone

unpunished by >od so that 3$ the sinner(1 had no right to harm them. This may signify

the birth of )rusoe6s morality, for the remainder of his detainment on the island. Through

4riday, )rusoe fulfills an unwritten obligation to >od. The words upon which )rusoe

made his initial conversion, 1)all upon me in the day of trouble, and will deliver, and

thou shalt glorify me,1 function as an agreement between >od and )rusoe. )rusoe

needed a companion and >od furnished 4riday. )rusoe responded to this by glorifying

>od6s name to 4riday; he converted 4riday to )hristianity.

This 1contract1 is merely a symbolic interpretation. )rusoe never explicitly mentions the

already mentioned words of >od as the motive for 4riday6s conversion, nor does he cite a

contractual obligation to >od. :aybe the fact that )rusoe -/$5N6T mention an

obligation or contract signifies that )rusoe actually -- undergo a very strong religious

conversion while he was detained on the island. Now, perhaps )rusoe considers

glorifying >od 1matter"of"fact.1 At any rate, )rusoe did convert 4riday to )hristianity

and this conversion seems to have rested favorably with >od. Not too long after, 4riday

is converted. >od 1delivers1 )rusoe home, after 0obinson had spent thirty"five years

detained on the island.

)rusoe6s behavior when he returns home is a testament of his religious ambivalence. t is

evident that )rusoe is a changed man. 3owever, he doesn6t really attribute his change to

>od. As a matter of fact, >od seems to have become a secondary factor in his life.

)rusoe affirms his belief in >od, and won6t be shaken from his belief. This is evident in

his selling of his plantation in ?razil. 3e sold it because he feared religious persecution.

?razil was in the midst of the 5panish n%uisition, and )rusoe had no intentions of

converting from 8rotestant to 0oman )atholicism in order to escape the n%uisition.

3ere, one sees )rusoe6s belief in >od, but what does this belief mean2

-oes his belief mean faith and devotion to >od2 t appears not. !hen )rusoe arrives in

$ngland, he doesn6t go to )hurch to thank >od for his safe homecoming. 3e rather

in%uires about his financial situation. )rusoe is generous when he returns to $ngland&he

supports the widow(, but how much of this generosity does )rusoe attribute to >od6s

workings2 None. )rusoe6s 1generosity motives1 are clearly secular. 3e responds to

kindness. )rusoe6s actions aren6t controlled by spiritual obligations. n short, it seems that

)rusoe has gained a true, underlying belief in >od through his experiences on the island,

but that this belief becomes secondary to his own life once his detainment on the island is

over.

Now, can one term )rusoe a 1true convert12 ?efore he was detained on the island, )rusoe

had no belief or fear of >od. -uring his detainment on the island however, )rusoe

1finds1 >od, and returns to $ngland with a belief in >od. n this sense, one can say that

)rusoe has converted. !hereas he had no belief in >od before he was detained on the

island, )rusoe returns with a very strong belief, a belief that even caused him to sell his

rich plantation. 3ow far does this belief take )rusoe though2 /n the island, )rusoe set

aside parts of every day in order to pray to >od. ?ack in $ngland however, )rusoe hardly

communicates with >od at all. ?y the end of the novel, the reader sees )rusoe returning

to his old self. 3e ignores the warnings of the old widow and sets out to find 1his1 island.

$ven with a belief in >od, then, )rusoe is ruled by impulse.

/ne can conclude then that )rusoe experienced a 1partial1 conversion. 3e is a convert in

the sense that he at least gained a belief in >od while detained on the island, but this is

where the conversion ends. The remainder of the faith that )rusoe displayed while on the

island evaporated once he returned back home. 3is faith on the island was convenient.

)rusoe, in this case, is the epitome of the 1convenient convert.1 3is great faith and

devotion to >od expired once his problematic situation was alleviated. The combination

of )rusoe6s belief, but shallow faith in >od, then, makes him a 18artial convert.1

" Call #im $riday: The E%itome of the Noble Savage in Robinson

Crusoe

/ne of the most important relationships that exist in -aniel -efoe6s 0obinson )rusoe is

that between )rusoe and 4riday, the 1savage1 who becomes )rusoe6s companion during

his last few years on the island. Aet, notice that although have termed 4riday as being

)rusoe6s 1companion,6 am using it in the strictest sense of the word. The use of the

broader definition would imply the presence of comradery or the )hristian idea of

1?rotherly 7ove.1 To use this definition is impossible. /ne cannot truly love another as a

brother when that other person is one6s slave, which 4riday apparently is. After all, 4riday

is not even worthy enough to call )rusoe by any other name but 1:aster.1 Not only is

4riday a slave, but he fits into the category of the 1Noble 5avage,1 the cannibal that can

be taught and trained how to be acceptable in )rusoe6s world. )rusoe even presents

4riday6s physical appearance in a manner acceptable to his readers. he makes him seem

$uropean. )rusoe states that.

3e had a very good countenance, not a fierce and surly aspect, but seemed to have

something very manly in his face, and yet he had all the sweetness and softness of an

$uropean in his countenance too, especially when he smiled. 3is hair was long and black,

not curled like wool; his forehead very high and large; ... The color of his skin was not

%uite black, but very tawny; and yet not of an ugly yellow, nauseous tawny, as the

?razilians and <irginians ... but of a bright kind of a dun olive colour that had in it

something very agreeable, though not very easy to describe. 3is face was round and

plump; his nose small, not flat like the Negroes6, a very good mouth, thin lips, and his

fine teeth well set, and white as ivory &-efoe, +B,(.

)rusoe 1alters1 4riday6s appearance. Aes, his hair is black, but it is not curled like

wool. 3ave no fear, no low brow here@ 3e6s 1not %uite1 black "" he6s TA!NA""

tanned by the sun, and his facial features do not represent those of the Negroes either.

Now that we have proven how physically acceptable 4riday is, let us look at some of the

even more 1pleasing1 aspects of his attitude.

4riday &if that6s what your name really is( is a very complying man. 3e is given 1truths1

by )rusoe which he readily accepts. A perfect example can be found in the title of the

nineteenth chapter""1 )all 3im 4riday.1 Aes, and that is ;ust how it is. t is not 13is

Name is 4riday1 or 1The )losest That )an )ome to 8ronouncing 3is Tribal Name is

4riday.1 )rusoe gives the name to the man, and the man does not ob;ect &at least as far as

we know from what )rusoe tells us(.

?ut, is this not how )rusoe deals with every barrier in their relationship2 The way that

things are to be done is )rusoe6s way, not anyone else6s. )rusoe teaches 4riday $nglish,

but does learn any of 4riday6s language. )rusoe does not point to a goat and say 1This is a

goat1 and then signal to 4riday to say what it is called in his language. )rusoe points to a

goat and says 1This is a goat"" end of discussion.1 )rusoe even clothes 4riday in his way.

)rusoe6s reason for the donning of clothes was that the sun shone too brightly on his

unprotected white skin. Aet, )rusoe cannot let go of the social convention that one cannot

go running around half naked""only 5A<A>$5 do that. 4riday is obviously comfortable

and 1protected1 by his 1tawny1 skin in this environment, but )rusoe dresses him anyway

in accordance with $uropean convention.

An important aspect that )rusoe replaces of 4riday6s is his religion. 3e converts 4riday to

)hristianity with the same explanation that are used by missionaries""that of 8rovidence.

... had not only been moved myself to look up to 3eaven and to seek to the 3and that

had brought me there, but was now to be made an instrument under 8rovidence to save

the life of, for aught knew, the soul of a poor savage, and bring him to the true

knowledge of religion, and of the )hristian doctrine, that he might know )hrist 9esus, to

know who is life eternal ... &-efoe, +'C(

As expected, 4riday is only too willing to embrace his master6s beliefs. 3e does so well

that )rusoe even remarks on how 1The savage was now a good )hristian, a much better

than ...1 &-efoe, +'C(. ?ut, perhaps the most important thing that )rusoe does &and the

thing that find the most terrible( is that he does not even see 4riday6s needs as relevant

enough to mention. The best example of this is when they leave the island before 4riday6s

father and the other shipwrecked $uropean sailors return from 4riday6s island &-efoe,

)hs.+,,+D(. )rusoe never even stops to think of how this will affect 4riday, and we never

hear of 4riday6s opinion on the sub;ect. find it very hard to believe that he would forget

about his father out of his 1love1 for his master, especially when we are shown how

emotional he becomes upon finding his father on the island &-efoe, )h.+'(.

Thus, have a problem believing that all of 4riday6s compliancy to )rusoe is done out of

love. believe that there is an aspect of fear working as well. 7et us go back to the scene

in which )rusoe saves 4riday from his captors. )rusoe states that.

The poor savage who fled, but had stopped, though he saw both his enemies fallen and

killed, as he thought, yet was so frightened with the fire and noise of my piece, that he

stood stock still and neither came forward or went backward, though he seemed rather

inclined to fly still than to come on; holloed again to him, and made signs to come

forward, which he easily understood, and came a little way, then stopped again, ..and

could then perceive that he stood trembling, as if he had been taken prisoner, and had ;ust

been to be killed, as his two enemies were &-efoe, +BB(.

n a book entitled Marvelous Possessions: The onder of the !e" orld, the author,

5tephen >reenblatt, discusses how '' ... the experience of the marvelous, central to both

art and philosophy, was manipulated by )olumbus and others to the service of colonial

appropriation1 &>reenblatt(. /ne of >reenblatt6s central themes and concerns is that of

1wonder1 and its effect. 3e states that.

A moderate measure of wonder is useful in that it calls attention to that which is 1new or

very different from what we formerly knew, or from what we supposed that it ought to

be1 and fixes it in the memory, but an excess of wonder is harmful, -escartes thought, for

it freezes the individual in the face of ob;ects whose moral character, whose capacity to

do good or evil, has not yet been determined. That is, wonder precedes, even escapes,

moral categories. !hen we wonder, we do not yet know if we love or hate the ob;ect at

which we are marveling; we do not know if we should embrace it or flee from

it&>reenblatt, +B(.

The above citation expresses the predicament that 4riday is in when he is saved by

)rusoe. 3e is left in awe by the power of )rusoe6s gun. $ven )rusoe himself states that

1... that which astonished him most was to know how had killed the other ndian so far

off ...1 &-efoe, +B'(. To 4riday, this is something that cannot be believed without going

over to the man and seeing the bullet hole for himself. 3e stands like 1 ... one amazed,

looking at him, turned him first on one side, then on t6other...1 &-efoe, +B'(.

This reaction of 4riday6s parallels once again with >reenblatt when he states that.

!onder""thrilling, potentially dangerous, momentarily immobilizing, charged at once

with desire, ignorance, and fear""is the %uintessential human response to what -escartes

calls a 1first encounter1 &p.,EF(. 5uch terms, which recur in philosophy from Aristotle

through the seventeenth century, made wonder an almost inevitable component of the

discourse of discovery, for by definition wonder is an instinctive recognition of

difference, the sign of a heightened attention, 1a sudden surprise of the soul,1 as

-escartes puts it &p. ,G+(, in the face of the new. The expression of wonder stands for all

that cannot be understood, that can scarcely be believed. t calls attention to the problem

of credibility and at the same time insists upon the undeniability, the exigency of the

experience &>reenblatt, +B(.

feel that )rusoe6s 1power1 cannot be believed by 4riday because he has no explanation

for it. 4or all he knows, )rusoe could be a god. feel that 4riday bows to )rusoe not only

out of love for saving his life, but out of the fear that )rusoe can take it away as

mysteriously as he did the lives of his captors.

5o could it, be possible that )rusoe has misinterpreted the 1signs1 that 4riday has given

him2 or, at least, misinterpreted the motives behind them2 )rusoe states that.

... smiled at him and looked pleasantly and beckoned to him to come still nearer; at

length he came close to me, and then he kneeled down again, kissed the ground, and laid

his head upon the ground, and taking me by the foot, set my foot upon his head. this, it

seems, was in token of swearing to be my slave forever &-efoe, +BB(.

According to >reenblatt, 1... charades or pantomimes depend upon a shared gestural

language that can take the place of speech1 &>reenblatt, FH( . $ven though too saw

4riday6s bowing as an act of subservience, thought of a couple of different meanings

that it could have. t could have meant 1 am indebted to you forever1 or 1 will love you

forever.1 /wing someone your life does not necessarily mean that you are to be their

1slave forever,1 as )rusoe seems to believe. )rusoe never once considers that 4riday

could be his 1friend forever.1 3e cannot even think of a non"$uropean in those terms.

Thus, apply the term of 1Noble 5avage1 to 4riday, as represented by )rusoe. s that not

the perfect way of presenting 4riday to his readers without causing their dismay2 s not

the 1)hristianizing1 of 4riday also one of )rusoe6s crowning achievements on the island2

Another one of his pro;ects to keep his mind off of things2 This may be so, but we will

never know for sure because we have never seen anything from 4riday6s point of view.

After all, everything else is done )rusoe6s way or it is not done at all""so why should the

telling of this story be any different2

!orks )ited

-efoe, -aniel. Robinson Crusoe# 5ignet )lassic. New Aork, 'HGB.

>reenblatt, 5tephen. Marvelous Possessions: The onder of the !e" orld# =niversity

of )hicago, 'HH'.

T#E C#ARACTER &$ R&'ERT (&)E(ACE

0obert 7ovelace is a man who is used to getting what he wants. 3e has been brought

up 1not to know what contradiction or disappointment is1 and he has managed to avoid

them throughout much of his life. 7ovelace was a very strong ego and a need for power

and domination. 3e needs to know he can control anything or anyone in any situation he

finds himself in. The only thing he can not control is himself. The desire to always have

his own way occasionally drives him to recklessness. 3e cannot stop himself when

pursuing something he wants. 3e usually gets it.

7ovelace is a charming, attractive man of wealth and status. 3e is well respected in

society, despite his reputation as a libertine. 3e behaves honorably in his dealings with

men and is trustworthy in money matters. $ven his enemy, 9ames 3arlowe, admits that

7ovelace is 1a generous landlord1 who looks after his own estate. t is only when it

comes to women that he is dishonorable, and many people are willing to overlook this.

7ovelace comes from a very highly regarded family, and they do not denounce him

because of his behavior. n fact they are often amused by his escapades. 7ovelace

entertains his ailing uncle with his tales of seduction, and his female cousins who are in

attendance also en;oy them. $ven after the tragedy of )larissa, when 7ovelace is

preparing to go abroad, his uncle says affectionately, 1!e shall miss the wild fellow.1

5eduction is 7ovelace6s greatest pleasure in life and his main goal is to sleep with as

many women as he can. 3e does it not for sensual pleasure, but for the challenge, the

excitement, the power he feels in being able to break down a woman6s defenses. 7ovelace

believes that all human beings have an animal, sexual nature. 3e views female modesty

and decorum as something superficial, a false persona that society forces on a woman in

opposition to her true nature. 7ovelace6s aim is to break down the barrier of virtue and

prove his theory that 1once subdued, always subdued.1 3e does not believe any woman

possesses genuine virtue, 1for what woman can be said to be virtuous till she has been

tried21 All the women that 7ovelace has tried he has con%uered.

The way 7ovelace speaks of his affairs and of women reveals his contempt for 1the

sex,1 as he calls them. 3e thinks he has women completely figured out, and he sees 1such

a perverseness in the sex.1 3e says 1they lay a man under a necessity to deal double with

them.1 7ovelace distrusts women. 3e feels he must play games and plot because they are

doing the same thing, and he can never be outwitted. !hen 7ovelace speaks of his affairs

with women, his language is often that of hunting, or even warfare. 1 love, when dig in

a pit, to have my prey tumble in with secure feet and open eyes, then look down upon

her.1 3e compares the capture of a woman6s virtue to the capture of a bird, saying, 1both

perhaps experience our sportive cruelty.1 And once the chase is over and the con%uest has

been made, 7ovelace feels the need to go on to the next challenge, bored with the woman

he ruined. 3e exclaims to ?elford, 1/ 9ack@ !hat devils are women when all tests are

over, and we have completely ruined them@1

7ovelace sees )larissa as the ultimate challenge because of her ex%uisite beauty and

excellent virtue. 5he is considered by many to be the perfect woman, held out as an

exemplar to her sex. 4or him to reveal to her, and to himself, that underneath all her

goodness and decorum she is merely a woman like any other, would be to him the

greatest victory of all. 7ovelace asks, 1!ill it not be to my glory to succeed2 And to hers,

and to the honor of her sex, if cannot2 !here will be the hurt to make the trial21 A self"

proclaimed marriage"hater, 7ovelace nevertheless says he will marry if he cannot sleep

with her without benefit of marriage. ?ut he intends to try everything possible before he

will consider this step.

!hat 7ovelace wants is to possess )larissa body and soul, to make her wholly his,

1for she can be no one else6s.1 3owever, he underestimates )larissa6s will to belong to no

one but herself. )larissa is the exception to his rules. 3er strength, her will, and her sense

of self match his. !hat starts out as a game soon escalates into a fierce power struggle.

7ovelace insists that she must admit her love for him, say that she wants to marry him, let

down her guard with him. This violates )larissa6s nature, she can never do what he asks.

4or her, decorum is not a mask, it is a basic part of her, and she cannot do something so

much against her nature. 7ovelace vows 1her haughtiness shall be brought down to own

both love and obligation to me.1

)larissa knows she cannot trust 7ovelace, that she cannot give in to him on anything.

The inflexibility of her punctilio is her protection. ?ut this inflexibility infuriates

7ovelace and causes him to become more ruthless and determined in his schemes. 3e

takes a drug that makes him sick in order to gain her sympathy. 3e uses the occasion of a

fire in the middle of the night to frighten and disconcert her, and to gain the opportunity

to get close to her while she is not fully dressed. The failure of these tricks only makes

7ovelace more obstinate, and he demands, 13ow, having proceeded thus far, could

stop21 Adding fuel to the fire are the whores at the brothel where he is keeping )larissa.

They taunt him and goad him, and ego will not let him stand it. 3e does not want to seem

weak or foolish in anyone6s eyes.

)larissa6s first escape pushes 7ovelace over the edge. 3is true obsessions and lack of

self" control are revealed. 3e will do anything to get )larissa back under his control. 3e

hunts her down frantically, and he tells ?elford that it has now come down to 1!ho shall

most deceive the other21 7ovelace will stop at absolutely nothing now, and his schemes

become more elaborate and diabolical. 3e disguises himself, forges letters, and produces

phony relatives in an effort to imprison her again. Through it all, 7ovelace blames

)larissa for 1contriving to rob me of the dearest property had ever purchased.1 3e

vows, 1my sworn revenge &adore her as will( is uppermost in my heart.1

7ovelace6s revenge is to drug and rape )larissa. 3e admits 1there6s no triumph over

the will in force, but have not tried every other method21 3e has tried her virtue and

found it to be sincere and pure, but he is in such a frenzy, he has driven the stakes so

high, that he cannot possibly allow himself to admit defeat. That would mean that his

whole belief system is wrong, that his life is based on a lie, and he cannot face that. 17et

me perish if she escape me now.1 7ovelace still clings to the belief that )larissa will be

subdued, and is convinced that he can make everything right by marrying her.

3owever, though )larissa is physically defeated, her will and her spirit cannot be

broken. 5he would never consent to marry someone who abused her and robbed her of

her dignity. 7ovelace cannot understand this, and he is too self"centered to try. 3e says

1she has but met the fate of a thousand others,1 and cries, 1 suffer a thousand times more

than ever made her suffer.1

)larissa6s final escape is death, which she chooses as her only alternative after all she

has been through. ?ut even this tragedy cannot truly change 7ovelace. 3is pride, his will,

and his obsession to possess )larissa persist up to and after her death, and even cause his

own. 3e wants to marry her on her death bed, although she was in agony.1 And after her

death he insists 1nobody will dispute my right to her.1 7ovelace6s wish to keep her heart

in a ;ar 1preserved in spirits1 shows ;ust how perverse and obsessed he can be.

7ovelace does express regret and sorrow for what he has done, but it is doubtful he

ever realizes the true evilness of it, or the real horror he put )larissa through. ?ut the full

knowledge of what he has lost and why he has lost it make life too much for 7ovelace to

bear, and he says, 1 have been lost to myself and to all the ;oys of life.1 3owever, his

pride has not been lost, and this is what leads him to the fatal duel with )larissa6s cousin

:orden. !hen 7ovelace hears that :orden has been talking of revenge for )larissa6s

death, his reaction is 1 am as much convinced that have done wrong as he can be, and

regret as much. ?ut will not bear to be threatened by any man, however conscious may

be of deserving blame.1 7ovelace dies with )larissa6s name on his lips. 3is death is

inevitable because he could not have lived without )larissa. believe he might have

loved her, if his nature would have allowed it.

C(AR"SSA

)larissa is a personal story about a young woman who is in conflict with her family

because of her opposing their insistence upon her marrying 5olmes, a man whom she

detests. As a direct conse%uence of her failure to yield to their increasing pressure and

urgency, poor )larissa gives in to the temptation of running off with 7ovelace as her only

viable means of escape from a life of unhappiness. =nfortunately, this action leads her

not to freedom from oppression, but to yet another battle of wills, which has dire

conse%uences for her. 5he falls victim to his greedy, selfish passion to con%uer her

through his vile rape and suffers a subse%uent decline in health, ending in her untimely

death. This utterly personal story is made public due to the elevated regard for )larissa by

all who knew her personally and even those who only knew her by reputation, as a model

of the perfect, dutiful daughter, the epitome of goodness, purity and punctilio,

representing the ideal young woman. n creating this work, 0ichardson used the element

of publicity to help convey his own ideas that morality is not ;ust a personal issue, but a

public one as well.

n the very first letter, the reader becomes aware through Anna 3owe6s letter to

)larissa thata dispute between )larissa6s brother and )larissa6s prospective suitor, which

should be a privatefamily matter, has become a topic of public discussion. Anna says, 1

know how it must hurtyou to become the sub;ect of the public talk ... but that whatever

relates to a young lady, whosedistinguished merits have made her the public care, should

engage everybody6s attention.1

8ublic figures become well known because they are extraordinary in some way. :ost

of the characters in )larissa represent extremes, displaying characteristics through which

they create reputations for themselves. )larissa is renowned for her virtue and goodness;

everyone regards her as the perfect young daughter, a model for her sex. 7ovelace is

infamous for his dalliances with women; he is a known rake. 8eople6s images are

important to them. $veryone tries to keep up his image because images help define a

person6s conceptions of himself as a human being; a tainted reputation would damage

one6s sense of pride.

?oth )larissa and 7ovelace are proud, opposing beliefs about what constitutes the

ideal maleIfemale relationship. ?oth adhere to their own personal views of the social

code; )larissa represents the puritanical, conventional mode of social conduct, while

7ovelace represents the more liberal attitude of the aristocracy. Though they are attracted

to each other, they have opposite philosophies about sex. 7ovelace feels that once he

possesses her physically, she will be forever under his spell, happy to be with him; all he

has to do is free her animal nature, which he believes existent in all women underneath

the polished facades created by society. )larissa sees her virtue as tantamount to her

honour, the core of her spiritual identity. !hen 7ovelace fails to win her over to his way

of thinking through his charm, he resorts to villainous force and rapes her, totally

disregarding her pitiful pleas to leave her alone. 4rom that point on, )larissa despises him

with a passion, refusing to listen to advice from Anna or anyone else to marry him. After

his heinous betrayal of her honor and her trust, she never wants him near her again.

!hen )larissa tells Anna, 1 could have loved him,1 have the impression that at

least part of her anguish stems from her bitterness in that she did actually love him at one

point. ?ecause she had loved him, this made his offense even more horrific and

unacceptable to her mentally, so that she loathed him with a venom and could never

forgive him, despite anything she says to the contrary. Also, think that part of her anger

has to be self"directed due to her own mis;udgment of his character. 3er sense of having

been physically and psychologically violated so cruelly to the core of her being by the

man she loved, her subse%uent loathing of him and her anger at herself for ever loving

such a man prove to be very detrimental to her health. 5he may even continue to feel love

for him in spite of her deep anger, resentment and loathing of his odious behavior,

creating an anguished, divided mind.

t is no wonder that she goes into such a physical decline after the trauma of being

raped. 5he had already been feeling extreme unhappiness and a sense of betrayal due to

her family6s unreasonable demands that she marry a man she abhors. 5he is very young,

only eighteen going on nineteen years old, and has been used to being treated well by her

family in the past. 5he always went along with her parents6 wishes before, but never

before were the stakes so high. To go along with their wishes on this issue would mean

sacrificing any chance for her own future happiness. To )larissa, this would be a fate

worse than death.

5everal times in the book, she mentions that she would rather die than be married to a

man she despises. 5he tells her family that she would rather never marry at all, but would

choose to remain single instead of marrying 5olmes. 5he promises to give the family the

dairy which was be%ueathed to her by her grandfather, all to no avail. They are resolute in

their insistence that she comply to their wishes. 3er mother, who used to tell )larissa that

she was 1all her ;oy,1 does not come to her defense, but gives in to her husband6s

unreasonableness. !hen on p. ,' )larissa says to her mother, 1Thus are my good

%ualities to be made my punishment; and am to be wedded to a monster,1 :rs. 3arlowe

answers, 1Astonishing@)an this, )larissa, be from you21 )larissa responds, 1The man,

madam, person and mind, is a monster in my eye.1 Any sensible, normal, loving parents

would not submit their young daughter to such a dismal fate as to force her into such a

hateful life. ?ut her mother is in an unhappy marriage herself, where she has sacrificed

her own individuality because it is easier to ;ust go along with her husband and keep the

peace. 3er mother fails to come to her aid. Also, :rs. 3arlowe feels that she must

present a united front with her husband to maintain the impression that all is well within

the family for the sake of public scrutiny.

)larissa is the only member of her family who does not appear to be afflicted with

greed. :aterial things are unimportant to her; she is more spiritually oriented. The rest of

the 3arlowes consider wealth and prestige so important that they have devised a plan to

raise their family6s social and economic status. The two uncles have agreed never to

marry, so that they could leave the bulk of their wealth to their nephew when they die,

thus giving him an opportunity to marry up into the aristocracy. 5ince they would be dead

anyway, how could it matter to them if the family becomes upwardly mobile2 The

answer is that 1the family1 is important to them, and how they are seen in the public eye

is crucial.

Although they are already a solid, wealthy, upper middle class family, they are not

content with this position. The public social climate of the time seems to foster an

upward"mobility mentality which the 3arlowes swallow hook, line, and sinker with little

regard for personal happiness, especially concerning )larissa. They are ready to 1sell1

)larissa off to 5olmes, the highest bidder, who in turn is willing to pay lots of money to

her family for the privilege of marrying up in social status himself. The fact that )larissa

finds him totally revolting is irrelevant to them. !ere it not for this generally accepted

practice to seek higher social status, there would be no reason to inflict this marriage on

)larissa.

?ut there is more to it than this. )larissa6s brother and sister are ;ealous of her since

she is the one who received the grandfather6s estate. )larissa has always been the one of

the children who has been loved and admired by everyone in the community, who see her

as a pure and precious pearl of a child, the ideal young woman and daughter. They talk

about her already having 1out"grandfathered us1 &p.+D( and worry that maybe other

relatives will also be%ueath their fortunes to her rather than themselves. Their family

1plan1 could be in danger. 9ames puts pressure on his father to marry )larissa off for a

large sum of money to help the family ac%uire wealth. 5ince 7ovelace is in a higher

social class as the 3arlowes, it would not be economically in their favor to approve

)larissa6s marriage to him; he would not pay them exorbitant fees for the 18rivilege.1

-ue to their concern for what amounts to their seeking public approval through

higher family status, )larissa6s parents fail in their duties to their youngest child by

abusing their authority to the point of trying to force her into a hateful marriage. )larissa,

heretofore an exceedingly dutiful daughter, does not even insist that she choose her own

husband, only that she be allowed veto power. ?ut this is denied her. 4or )larissa, this

creates an irreconcilable inner conflict, as she is very uncomfortable with defying her

parents, but at the same time refuses to sacrifice herself to a life of unhappiness. !hen

she runs off with 7ovelace, it is in pursuit of self" preservation; she is running for her life.

?ut she is absolutely mortified and devastated when she receives the curse from her

father.

t is this horrendous treatment she receives through the hands of her family and by the

cruel 7ovelace that cause her to become ill. Aet, though she becomes physically weak,

spiritually, she seems to be getting stronger. t is as though as her body deteriorates, her

spirit becomes elevated. 0ichardson manages to enhance this effect by making her illness

and her death very public. Through ?elford, she is able to orchestrate the details

concerning her will and last re%uests in preparation of her death. Jnowing that she is

dying and welcoming it, one of her chief concerns is setting the record straight about her

experience with 7ovelace. 5he is determined to clear and preserve her reputation and

goes to great lengths to do this, even so far as to have ?elford obtain copies of 7ovelace6s

letters alluding to her innocence.

$ven in thinking about her own death, her image is paramount to her, her passion for

decorum apparent in her wearing pure white garments as if she were an expectant happy

bride, but also symbolic of a sacrificial lamb, awaiting death with open arms, longing to

be laid in her waiting coffin. 4riends and family visit her at her deathbed, observing her

as being not ;ust good and pure, but as a manifestation of a heavenly angel, a saint here

on earth. 5ervants come forward for a last blessing by her. )larissa is still worried about

her father6s curse and wishes him to retract it. !hen she talks to her doctor, she expresses

concern that her coming death not implicate suicidal desire. 5he asks the doctor if she has

taken everything she should to combat death. 3er image is everything to her; it must

remain unblemished. t is important to her what people will think of her, even after her

death.

Approaching death, )larissa seems to become ever more peaceful, as she realizes that

this is the best, perhaps the only, acceptable solution to her agonizing ordeal of the last

eleven months. 5he must realize that everyone sees her as an innocent victim to her

family6s obsession for the ac%uisition of wealth, and 7ovelace6s obsession to possess her.

3er innocence apparent, she comes out smelling like roses , but her death gives her

power, power to achieve passive revenge on the perpetrators of her acute unhappiness. t

is poetic ;ustice that 7ovelace also undergoes a rapid decline in health and dies a

miserable death after having defiled )larissa, a paradigm of virtue. t is also poetic ;ustice

that as )larissa6s family abused her through want of public approval through their %uest

for wealth and status, they would henceforth suffer severe public disapproval for their ill

treatment of such an extraordinary virtuous daughter, paying for their crimes with the

shame of never again being able to hold their heads up, scorned for the rest of their

earthly days.

Although morality involves personal choices, one6s actions can have public

ramifications of great magnitude, not ;ust personal ones. 8eople do not live in a vacuum.

t seems that 0ichardson wanted to present a message that actions have conse%uences and

affect others, sometimes precipitating unpredictable, dire, irreconcilable outcomes.

believe that he felt that everyone has a personal as well as a social obligation to act in

morally responsible ways, and that a breach of moral conduct and abusing one6s position

by inflicting pain on others is deserving of public condemnation.

*EN AND "N+

/f all the attachments set forth in 5amuel 0ichardson6s Clarissa, perhaps none is

stronger than that of the heroine to her writing implements. 5he takes great care to

possess these, partly because she has to""she knows her parents may at any time seek to

obstruct her by taking them away""and part@y because she is ;ust that kind of person; she

will always have pen and ink with her because she is always writing.

Near the beginning of the story she describes the measures she takes to persist in this,

her vocation; on April E she relates to :iss 3owe.

must write as have opportunity; making use of my concealed stores. for my pens and

ink &all of each that they could find( are taken from me; as shall tell you more

particularly by and by &'(.

4urther in the same letter she reports ?etty, the maid, as saying, 1 must carry down your

pen and ink1; this is followed by her cousin -olly6s regretfully insisting, 1...Aou must""

indeed you must""deliver to ?etty""or to me""your pen and ink1 &+(. Thus it is established

early on that )larissa6s writing tools are not only, in her parents6 eyes, instruments of her

insubordination, but, in the eyes of the reader, they become symbols of her dedication to

writing. Nothing can separate her from them, nor will she ever allow herself, except in

moments of utmost duress, to be without the means, and the will, to use them.

4or )larissa6s captors &first her parents, and later 7ovelace(, her writing becomes a

focus of their inability to control her completely. 5hortly after her pens and ink are

confiscated, her aunt tells her that the family is convinced that 1you still find means to

write out of the house.1&,( 7ater, 7ovelace determines that she will not be fully in his

power without his being able to monitor her correspondence; of the letters between

)larissa and Anna 3owe he writes &on :ay F, to ?elford(.

must, must come at them. This difficulty augments my curiosity. 5trange, so much

as she writes, and at all hours, that not one sleepy or forgetful moment has offered in our

favour &D(.

)larissa, ever vigilant of her most prized activity, of course suspects and even anticipates

7ovelace6s designs. /n April +G she warns :iss 3owe.

:r. 7ovelace is so full of his contrivances and expedients, that think it may not be

amiss to desire you to look carefully to the seals of my letters, as shall to those of yours

&E(.

3er wariness here does not prevent 7ovelace from successfully interfering, but it does

demonstrate her determination to protect her writing.

3er primary determination, to be engaged in the act of writing itself, is manifest in

numerous passages. /n April +B, she observes to :iss 3owe, 1ndeed, my dear, know

not how to forbear writing. have now no other employment or diversion1 &G(. To :rs.

9udith Norton she avers, 1 will write. ?ut to whom is my doubt1 &C(. !hen it is

suggested that she should share a bed with :iss 8artington, who will wait up with -orcas

until )larissa is done writing, she replies that 1...:iss 8artington should be welcome to

my whole bed, and would retire into the dining"room, and there, locking myself in,

write all the night1 &F(.

This last statement reminds us that essential to the writer6s vocation is the condition of

solitude, for which )larissa displays a like determination. 1The single life,1 she observes

on 9uly +, to :iss 3owe, 1...has offered to me, as the life, the only life, to be chosen1 &H(.

The next day 7ovelace reports to ?elford.

The lady shut herself up at six o6clock yesterday afternoon, and intends not to see

company till seven or eight this; not even her nurse""imposing upon herself a severe fast.

And why2 $t is her %$RTH&A'( &'B(.

Thus there is no greater present that )larissa can give to herself than solitude""and the

opportunity to write.

!hen :rs. 3owe forbids her daughter to receive further letters, :iss 3owe over"

rules her mother, saying, 1?ut be assured that will not dispense with your writing to me.

:y heart, my conscience, my honour, will not permit it1 &''(. )larissa, in response,

declares.

forego every other engagement, suspend every wish, banish every other fear, to take

up my pen, to beg of you that you will not think of being guilty of such an act of 7ove as

can never thank you for; but must for ever regret. f must continue to write to you,

must &'+(.

t appears that the regret expressed here is simply for defying the parental authority of

:rs. 3owe; )larissa regrets not at all :iss 3owe6s insistence on continuing to receive

her letters. And, incidentally, :rs. 3owe seems to have ambivalent feelings about cutting

off )larissa6s correspondence. Near the end Anna writes.

Aou are, it seems &and that too much for your health(, employed in writing. hope it is in

penning down the particulars of your tragical story. And my mother has put me in mind

to press you to it, with a view that one day, if it might be published under feigned names,

it would be of as much use as honour to the sex. :y mother says K...L she would be

extremely glad to have her advice of penning your sad story complied with &',(.

$vidently, whatever apprehensions :rs. 3owe has about the corrupting influence of

)larissa upon her daughter are overcome by an eagerness not to miss out on what

)larissa will write. )larissa6s reputation as a writer is widespread. 7ord :. comments to

7ovelace, 1... for am told that she writes well, and that all her letters are full of

sentence1 &'D(. After she escapes 7ovelace, he complains to ?elford, 1 have no doubt,

wherever she has refuged, but her first work was to write to her vixen friend1 &'E(. $ven

Arabella ;ealously admits the power of her sister6s prose, beginning a letter &;ust a month

before )larissa6s death( as follows.

5ister )lary,"" wish you would not trouble me within any more of your letters. Aou had

always a knack at writing; and depended upon making every one do what you would

when you wrote &'G(.

)larissa maintains her output until the very end, despite the difficulty it gives her.

?elford reports on August +F to 7ovelace, 1:rs. 7ovick told me that she had fainted

away on 5aturday, while she was writing, as she had done likewise the day before1 &'C(.

The day before she dies, )larissa is too weak to hold a pen, but she dictates to :rs.

7ovick what will be her last letter, for :iss 3owe. 1Although cannot obey you, and

write with my pen, yet my heart writes by hers1 &'F(.

t is tempting if not entirely ;ustifiable to see )larissa as representing somewhat the

writer6s condition. ?esieged by the interfering forces of family, suitors, and society,

hailed as a paragon and regarded as an oddity, abused, exploited, and made to suffer

numerous hardships, she nevertheless manages to demonstrate stamina and perseverance

in her chosen form of expression, her art.

t is doubtful, however, that this was 0ichardson6s intention. 3e wanted )larissa to

represent moral, not literary, virtue. 3er prolific letter"writing is simply a by"product of

circumstance""what the situation demands""as well as an expedient for telling the story in

epistolary form.

This is too bad, for otherwise her writing might have saved her. 0ichardson must

have had a grudge with the world, and decided to show that )larissa was too good for it.

3e let death stop her; he had her, in effect, choose to die. ?ut if )larissa was what she

seems, if she was as attached to her vocation as she shows herself to be, would she have

done this2 )ould her troubles have killed her2 No matter how ill and dispirited she was,

might she not have endured simply to avoid relin%uishing her pen and ink2

$&&TN&TES

&'( 8age ''B. This and the following page references are from 5amuel 0ichardson,

Clarissa) or The History of a 'oung *ady, abridged and edited by >eorge 5herburn,

&?oston. 3oughton :ifflin, 0iverside $ditions, 'HG+(.

&+( 8age '''.

&,( 8age '+D.

&D( 8age +'E.

&E( 8age 'HC.

&G( 8age 'F'.

&C( 8age ,DE, from letter of 9uly G.

&F( 8age +BG, from letter or :ay '.

&H( 8age ,H,.

&'B( 8age ,HC.

&''( 8age +BC, from letter of :ay ,.

&'+( 8age +BF, :ay D.

&',( 8age DBC, letter of 9uly +F.

&'D( 8age +DC, letter of :ay +,.

&'E( 8age +CC, letter of 9une F.

&'G( 8age D+B, August ,.

&'C( 8age DDB.

&'F( 8age DGC, 5eptember G.

DECE*T"&N AND D"S,-"SE "N A SICILIAN ROMANCE

by Ann":arie 3enry"5tephens

n naming her novel A Sicilian Romance, Ann 0adcliffe may have attempted to

deliberately deceive her readers by disguising the artistic complexities of this novel with

its simple title. This novel is full of intrigue, suspense, tyranny, drama and villainy. t

allows the reader to experience emotions ranging from fear and disgust to love and

sympathy. 7ike the many characters who get lost in the recesses of the castle, the forests,

the monastery, the ruined buildings, and the 5icilian landscape, so too do the readers get

lost to the outside world when engaged in the plots and sub"plots of this novel. The

>othic elements& the haunted castle, the possible supernatural presence, the decay, and

the dark gloomy environs( used in the novel help to enhance its richness and

mysteriousness. The characters themselves are the most intriguing, for they embody the

deceitfulness and the disguises which force the readers to want to discover all that lies

behind the walls of the :azzini castle.

4erdinand, fifth mar%uis of :azzini, a ruthless, tyrannical leader, heartless father, and

cruel husband &to his first wife 7ouisa ?ernini( was the personification of deceit. 3e had

power, and he used it mercilessly and arrogantly. 3e ruled by overpowering, threatening,

lying to, and manipulating others. !hen he met and fell in love with :aria de <ellerno,

he sought to get rid of the woman he was already married to, without care for her or for

her children. 3e imprisoned the ailing 7ouisa in the southern wing of the castle and then

told everyone that she was dead. The mar%uis further compounded his deception by

holding a funeral for 7ouisa 1with all the pomp1 due to her rank. 3e enlisted the help of a

servant, <incent, who was totally dependent on and in awe of him, to carry out his plans.

n relating the story of her imprisonment 7ouisa said of him, 1:y prayers, my

supplications, were ineffectual; the hardness of his heart repelled my sorrows back upon

myself; and as no entreaties could prevail upon him to inform me where was, or his

reasons for placing me here, remained for many years ignorant of my vicinity to the

castle, and of the motive of my confinement1 &'CC(. n fact, the mar%uis never told the

marchioness why she was being held, and she only gained this information through the

6softening6 of <incent6s heart.

The mar%uis6 deceitfulness knew no boundaries, for he went on to commit further acts

that would allow him to go undetected. 3e shut up the southern section of the castle, left

his daughters in the care of :adame de :enon, a dear friend of his first wife, and went to

live in Naples with his son and new wife for many years. After the death of <incent and

his subse%uent return to the castle, he still tried to cover his tracks. !hen :adame, the

girls and the servants saw lights appear in and heard sounds emitting from the southern

section of the castle, he dismissed their claims as, 1the weak and ridiculous fancies of

women and servants...1&'D(. 7ater on, when his son 4erdinand went to him with similar

claims, he chose to attack his mind and manhood. !hen 4erdinand persisted in his

claims, his father added to the mountain of lies, by telling him that the building was

haunted by the ghost of 3enry della )ampo, a rival of his &the mar%uis6( grandfather, who

had been killed there many years ago. 4erdinand was deceived, for he believed his

father6s story, especially since the mar%uis claimed that he himself had witnessed the

horror of seeing the ghost. The mar%uis also sought to deceive his superstitious and

fearful servants, by taking them to the southern section and showing them fallen stones,

which he claimed to be the cause of the sounds coming from that part of the castle. 3e

made sure to stop short of where his wife was hidden. They, however, were not placated

by his explanation.

The mar%uis was an ambitious man and did not hesitate to use whatever or whoever

he could to achieve his ambitions. !hen the -uke de 7uovo asked for his daughter

9ulia6s hand in marriage, the mar%uis saw an opportunity for himself there and consented

to the marriage solely on selfish grounds. 3e saw this marriage as a chance to gain more

1wealth, honor and distinction1 &EG(. 3e also saw a chance, at 9ulia6s expense and through

the duke6s means, to 1involve himself in the interests of the state1 &'FF(. The mar%uis

sought to deceive the -uke also, for after 9ulia succeeded in running away from the castle

and her nuptials, the mar%uis 1carefully concealed from him her prior attempt at

elopement, and her conse%uent confinement,1 thereby enraging the duke whose pride was

wounded by the insult. They %uarreled, but subse%uently made up, allowing the mar%uis

to gain a strong ally in his endeavors.

The -uke de 7uovo was very much like the mar%uis in character. 3e loved power,

and he exercised it at the expense of everyone. 3e had a violent temper and a very high

opinion of himself and his authority. 3e pretended to care deeply for 9ulia, when he was

really only interested in ac%uiring her because of her beauty. /nce she revealed her true

feelings to him, he was humiliated and inflamed so, with her father6s consent, sought to

have her anyway. After her flight he pursued her mercilessly, simply because his passion

for her 1was heightened by the difficulty which opposed it.1 9ulia was ;ust an ob;ect of

his desire and his pride.

The duke had another thing in common with the mar%uis; he too had a child who had

run away from him. 3is son, 0iccardo, had run away from him many years before, and he

had never been able to find him. !hen he finally did encounter him, he was surprised to

find him disguised as a banditti. 0icardo, after running away from his father, 1had placed

himself at the head of a party of banditti, and, pleased with the liberty which till then he

had never tasted, and with the power which his new situation afforded him,1 was a

contented young man &FF(. 3e knew that as a member of the nobility, if at any time he

chose to shed this disguise and resume his rank, it could be accomplished with minimal

explanations and scrutiny. 3is father6s pride was devastated, and so he wished his son

dead.

The true characters of 1the men of the cloth1 in this novel were curiously hidden from

the world outside their monasteries. /n his ;ourney to find 9ulia, the duke encountered a

monastery full of rowdy friars and a drunken 5uperior, whom he was initially told were

1engaged in prayer,1 when he sought refuge at their gate. The Abate, at the abbey of 5t.

Augustin, was another disguised individual. 3e used his position and authority to control

those around him, and to seek revenge on those who opposed him. 3e was not the

benevolent character that one would expect to find in his position. 3e used his power to

defy 9ulia6s father and he reveled in it. 3e accused 9ulia of using 1the disguise of virtue1

to gain his protection, but he instead tried to use her fear, her naivete, and her desperate

situation to force her to become a nun.

The 1fairer sex1 was e%ually deceptive, but their reasons, for the most part, were

based on love and self"preservation. 9ulia deceived her father not out of malice, but

because of fear for the life she would have to live and because of her love for 3ippolitus.

5he also deceived her sister $milia, because of her love for her and her need to protect

her from the mar%uis. 9ulia6s deceptiveness was not only in her actions, but in her

character, for she appeared to be a fragile girl who fainted or cried at every unbearable

thought or deed, but she was in fact a very strong woman. 5he openly defied her father,

fully aware of the conse%uences of her actions. 5he spent a very long time on the run,

never really giving up hope, and never returning to her father. 5he was determined never

to give in. A weaker woman might have returned home or committed suicide, rather than

live through her experiences, but 9ulia never entertained those thoughts. 5he, however,

found a woman like herself, who had made certain choices in her life, but this woman

was not able to live with her choices.

)ordelia, 3ippolitus6 sister, was in many ways disguising herself as a nun. 5he had

decided to 1take the veil,1 but her heart was not in her vows. 5he was still very much in

love with an earthly presence, Angelo. 5he may have succeeded in deceiving those

around her, but she could not deceive herself, hence her early demise.

The supreme mask was worn by :aria de :azzini, the wife of the mar%uis. This

woman was able to blind her shrewd and devoted husband. 5he was a beautiful woman,

with an explosive temper, a mean, ;ealous spirit, and the capacity to manipulate. 3er

strong desire to have 3ippolitus, and her intense ;ealousy of 9ulia, drove her to encourage

the marriage of 9ulia and the -uke de 7uovo. 5he also succeeded in having :adame de

:enon leave in order to save her reputation with her husband. 5he wrongfully assumed

that the :adame possessed the same spiteful %uality that she had. f anything, the

marchioness was the mar%uis6 one weakness. 5he did not really love him, for a woman

like that could only truly love herself. 5he was able to convince him of her devotion to

him, even though she had had numerous affairs while being married to him. 5he carried

on these affairs right under his very nose, but was never suspected by him. !hen he

finally discovered her treachery, via a servant, being so blinded by his feelings for her, he

was not able to carry out his initial plan of killing her. 3e, instead, chose to reprimand her

and this she used against him. 5he committed suicide, left a note blaming him for her act,

and informed him of his own impending death by her hand. 5he had been able to deceive

him one last time, when she poisoned his drink during their dinner the evening before.

The author6s biggest deceptive device though was the :azzini castle, the focal point

of the mystery. This building served as perfect cover for the characters, their actions, and

the secrets within it. The walls were able to hide much of what went on within them. The

castle hid information from the characters and from the readers. :adame de :enon,

9ulia, $milia, 4erdinand, and the servants did not know what was responsible for the

noises and lights in the southern section. The children did not know that their mother was

alive and living so close to them. 4erdinand was not aware that as he was languishing in

the dungeon, his mother was within a stone6s throw. :aria de :azzini did not know

about the first marchioness. The mar%uis did not know that :aria was having affairs right

there in the castle. 3e was not aware of her deceptiveness and her true character, which

enabled him to be killed by her. 3e was not able to prevent 9ulia6s escape from the castle

and he was not aware of her return to it. This castle was the ultimate mask, for the readers

never really see all of it and so cannot fully perceive all of its secrets, and so it retains its

air of mystery till the very end of the story.

.or/ Cited

0adcliffe, Ann. A Sicilian Romance. New Aork. /xford, 'HH,.

#uc/ $inn0s #ero 1ourney

by 9anet 3ouse

n his book The Hero ith a Thousand Faces, 9oseph )ampbell sets forth his theory

that there is a monomyth which underlies all folk tales, myths, legends and even dreams.M

0eflected in the tales of all cultures, including )hinese, 3indu, American ndian, rish

and $skimo, this monomyth takes the form of a physical ;ourney which the protagonist

&or hero( must undergo in order to get to a new emotional, spiritual and psychological

place. The monomyth is a guide which integrates all of the forces of life and provides a

map for living.

)ampbell breaks down the cycle into three main stages. departure, initiation and

return. !ithin these three stages are five to six steps through which the hero moves. 4irst,

the hero must leave his world and undertake a ;ourney into an unknown world, in effect

losing himself and descending into death. Next, he undergoes a series of tests, assisted by

various helpers, which can be very dangerous and threatening. These tests serve as

guideposts in his ;ourney, and from each the hero learns something which helps to move

him along. 4inally, the hero reaches the apex of his ;ourney, where thereMis an apotheosis

or transcendence. The hero, having evolved and emerged into his best possible self, must

return home carrying with him his new found knowledge or boon to restore the world.

4irst, 3uck as the hero is not of noble birth whereas most of )ampbell6s protagonists

are princes, princesses or divinely chosen in some way. !hile 3uck 4inn is special, he is,

nevertheless, an ordinary American boy which other American boys can identify with.

5econdly, magic and the supernatural play an important role in the tales )ampbell uses to

illustrate the hero cycle. n The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, however, there is no

magic. There is luck, coincidence &at times highly unlikely coincidence(, but there is no

magic or supernatural. This again brings the story to a level that Americans can identify

with. 4inally, 3uck6s return is of a different nature than the traditional ;ourney which

reflects a particularly American ideal.

3uck 4inn6s adventure begins when he sees his father6s footprint in the snow. =p to

this point, 3uck describes his daily, routine life, but the footprint signals a change.

3uck6s father functions, therefore, as the herald signaling the call to adventure by 1the

crisis of his appearance1 &)ampbell, E'(. As )ampbell states.

The herald or announcer of the adventure is often dark, loathly, or terrifying, ;udged evil

by the world; yet if one could follow, the way would be opened through the walls of day

into the dark where the ;ewels glow &)ampbell, E,(.

3uck6s father is portrayed as dark &morally, not physically(, loathly, terrifying and he is

indeed ;udged evil by the world, but it also he who precipitates 3uck6s ;ourney.

!hen 3uck6s father moves him into the woods, 3uck is in the first stages of his

;ourney. 3e is away from all that is familiar to him and the longer 3uck remains in the

woods, the more he ad;usts to the ways of life there. 3e cannot imagine going back to

civilization, wearing stiff clothes, minding his manners and all the other ways he has

ac%uired living with the !idow -ouglas. According to )ampbell, this alienation from his

previous life is part of the cycle.

The familiar life horizon has been outgrown; the old concepts, ideals, and emotional

patterns no longer fit; the time for the passing of a threshold is at hand &)ampbell, E'(.

3uck6s next step in his ;ourney is what )ampbell calls 1The ?elly of the !hale1.

1The hero . . . is swallowed into the unknown, and would appear to have died1

&)ampbell, HB (. n order to proceed, the hero must leave his world totally and die into

himself in order to be reborn again. 3e must relin%uish his ties with this world in order to

attain a higher level of existence, which is the purpose of his ;ourney.

?ecause 3uck fears for his safety, he realizes that he must leave the woods. Aet he

does not want to return to his previous life. Therefore, he elaborately stages his own

death, planning every detail carefully so that everyone will think he is dead and will not,

therefore, look for him and bring him back to the existence he has outgrown. This 1self"

annihilation1 is absolutely crucial for the ;ourney.

After his 1death,1 3uck floats down to 9ackson6s sland and spends three days and

three nights by himself &reinforcing the theme of death and rebirth( before the next stage

of his ;ourney. 3ere, 3uck meets up with 9im who is what )ampbell refers to as

15upernatural Aid1.

The first encounter of the hero";ourney is with a protective figure &often a little old crone

or old man( who provides the adventurer with amulets against the dragon forces he is

about to pass &)ampbell, GH(.

The fact that the aid often comes from a little old crone or an old man suggests that it

comes from someone whom society does not value. To have someone whom society does

not value provide essential elements to the ;ourney is ironic. As the provider of

1supernatural aid1 to 3uck, 9im, a 'Hth century black man, is not valued in human terms

by his society. ndeed, he is not even thought of as human, which further heightens this

irony.

!hile 9im does not literally provide 3uck with amulets against the dragon forces,

figuratively, he does. As )ampbell states. 1what such a figure represents is the benign,

protecting power of destiny1 &)ampbell, C'(. 9im cares for and protects 3uck, nurtures

him and loves him, both mothers and fathers him, calling him 1honey1 and watching out

for his safety. :ost importantly, however, 9im provides 3uck with a belief in humanity,

where all along the river 3uck sees evidence of man6s corruption and cruelty. This belief

is the amulet with which with 3uck will fight off the 1dragon forces,1 those forces being

man6s inhumanity to man.

The )rossing of the 4irst Threshold comes after 3uck has learned that two men are

on their way to the island. =p to this point, 9im and 3uck exist in a kind of limbo, both

having escaped their previous lives, but not going forward. At this point, they must move.

9im risks being captured and sold; 3uck risks a return to the life he has outgrown. They

must cross the threshold into the region of the unknown. Although this crossing is

dangerous, the hero must move beyond it in order to enter a 1new zone of experience1

&)ampbell, F+(.

At this point 3uck, as the hero, moves into the second stage of his ;ourneyNinitiation.

t is here where he encounters the 0oad of Trials.

/nce having traversed the threshold, the hero moves in a dream landscape of curiously

fluid, ambiguous forms, where he must survive a succession of trials . . . . The hero is

covertly aided by the advice, amulets, and secret agents of the supernatural helper whom

he met before his entrance into this region+illustrate &)ampbell, HC(.

These trials are tests for the hero which he must overcome in order to move forward in

his ;ourney. They serve as guideposts along the way, reflecting his progress and growth.

?y surviving these trials, the hero moves to a point of transcendence. The purpose of the

trials is to gain some kind of knowledge or insight which the hero needs in order to

complete his ;ourney. This leads to the %uestion. what is the purpose of 3uck6s ;ourney2

$very episode along the river in some way illustrates man6s inhumanity to man. :eeting

every walk of life, 3uck6s confrontation with this world illustrates cruelty and corruption

of some kind. !hile some characters are obviously corrupt &the king and the duke, for

example(, all characters are tainted somehow. $ven the most charitable characters""the

woman 3uck meets while dressed as a girl, the >rangerfords, the 8helps, :ary 9ane""are

tainted by their attitudes toward blacks or towards other people in general. 3owever,

3uck6s exposure to society6s corruption is balanced by the kindness he receives from

certain people and by the humanity he learns from 9im.

As a product of his society, 3uck believes in slavery and also believes he is doing

wrong by protecting 9im. ?ut 3uck comes to see 9im6s own humanity through their

friendship. 9im tells 3uck that he is the best and only friend he has, the only white man

who has kept his promise to him. 9im6s belief in 3uck6s goodness is essential to 3uck6s

physical as well as psychological ;ourney. This relationship teaches 3uck about caring

for another human being in the face of ubi%uitous cruelty. This is the more elevated

purpose of 3uck6s ;ourney. 3uck learns the techni%ues for humane survival""how to exist

in the cruel world and not be corrupted by it.

3uck6s trials finally come to a crisis when the king and the duke are attempting to

swindle the !ilks girls out of their inheritance. =p until this point, 3uck has remained

rather passive with regard to their antics. -isgusted by their behavior, however, 3uck

exclaims. 1t was enough to make a body ashamed of the human race1 &Twain, +FE(. 3e

decides that he must take some action and his dilemma is over how to help the girls.

8reviously, 3uck has lied to survive but here he realizes that his best option may be to

tell the truth. This is a moment of transcendence for 3uck as he rises above his

experience of the past and takes a chance in telling the truth. 1here6s a case where 6m

blest if it don6t look to me like the truth is better, and actually safer, than a lie1 &Twain,

+HH(.

This test also melds with what )ampbell calls 1The meeting !ith the >oddess.1

?ecause 3uck is only a boy, there will be no 1mystical marriage1 with the 1=niversal

:other,1 the 1incarnation of the promise of perfection.1 This is not to be a part of 3uck6s

;ourney. Aet :ary 9ane does inspire 3uck. 3e finds her beautiful and it is because of her