Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

Uploaded by

Salahuddin SultanOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

The International Journal of Human Resource Management

Uploaded by

Salahuddin SultanCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [INASP - Pakistan (PERI)]

On: 04 November 2013, At: 02:07

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered

office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

The International Journal of Human

Resource Management

Publication details, including instructions for authors and

subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rijh20

Can usefulness of performance

appraisal interviews change

organizational justice perceptions? A

4-year longitudinal study among public

sector employees

Anne Linna

a

, Marko Elovainio

b

, Kees Van den Bos

c

, Mika

Kivimki

d

, Jaana Pentti

a

& Jussi Vahtera

a

a

Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Unit of Excellence for

Psychosocial Factors , Turku , Finland

b

Department of Health Services Research , National Institute for

Health and Welfare , Helsinki , Finland

c

Department of Social and Organizational Psychology , Utrecht

University , Utrecht , the Netherlands

d

Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Unit of Excellence for

Psychosocial Factors , Helsinki , Finland

Published online: 06 Oct 2011.

To cite this article: Anne Linna , Marko Elovainio , Kees Van den Bos , Mika Kivimki , Jaana Pentti

& Jussi Vahtera (2012) Can usefulness of performance appraisal interviews change organizational

justice perceptions? A 4-year longitudinal study among public sector employees, The International

Journal of Human Resource Management, 23:7, 1360-1375, DOI: 10.1080/09585192.2011.579915

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.579915

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the

Content) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis,

our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to

the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions

and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors,

and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content

should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources

of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims,

proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or

howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising

out of the use of the Content.

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any

substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing,

systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Terms &

Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-

and-conditions

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

I

N

A

S

P

-

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

(

P

E

R

I

)

]

a

t

0

2

:

0

7

0

4

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

3

Can usefulness of performance appraisal interviews change

organizational justice perceptions? A 4-year longitudinal study among

public sector employees

Anne Linna

a

*, Marko Elovainio

b

, Kees Van den Bos

c

, Mika Kivimaki

d

, Jaana Pentti

a

and Jussi Vahtera

a

a

Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Unit of Excellence for Psychosocial Factors, Turku,

Finland;

b

Department of Health Services Research, National Institute for Health and Welfare,

Helsinki, Finland;

c

Department of Social and Organizational Psychology, Utrecht University,

Utrecht, the Netherlands;

d

Finnish Institute of Occupational Health, Unit of Excellence for

Psychosocial Factors, Helsinki, Finland

This large-scale longitudinal study examined the hypothesis that the experienced

usefulness of performance appraisal interviews affects justice perceptions and that

changes in work life contribute to this effect. Our ndings from 6592 employees who

were nested in 1291 work groups over a 4-year period and who at baseline had not

applied for a performance appraisal interview support this prediction. Specically, the

results of multilevel regression analyses showed that interviews that were experienced

as useful improved justice perceptions signicantly. In contrast, when the interviews

were experienced as unhelpful, the impact on justice perceptions was negative.

Furthermore, during negative changes in work life, useful interviews were especially

important in helping prevent the deterioration of justice perceptions. The implications

for organizational justice and the usefulness of the performance appraisal are discussed.

Keywords: interactional justice; performance appraisal interview; procedural justice;

usefulness

Introduction

Organizational justice is becoming an increasingly central question in the rapidly

changing work life (e.g. Konovsky 2000; Colquitt, Conlon, Wesson, Porter and Ng 2001).

Numerous studies have shown that justice predicts essential organizational outcomes, such

as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, motivation, performance, and

organizational citizenship behavior (e.g. Folger and Konovsky 1989; Moorman 1991;

McFarlin and Sweeney 1992; Korsgaard and Roberson 1995; Colquitt et al. 2001), and

also essential individual mental and physical health outcomes, such as sleeping, smoking

and drinking behavior, and emotional and bodily reactions (e.g. Tepper 2001; Kivimaki,

Elovainio, Vahtera, Virtanen and Stansfeld 2003; Kouvonen et al. 2007; Greenberg 2010).

Thus, justice is important in the organizational context.

Organizational justice refers to the extent to which employees are treated with justice

at their workplaces (for reviews, see e.g. Cropanzano, Byrne, Bobocel and Rupp 2001;

Greenberg and Colquitt 2005). Previous research has suggested that it is possible to change

justice perceptions within organizations (e.g. Skarlicki and Latham 1996, 1997; Cole and

Latham 1997). However, it is not known whether it is possible to change justice

ISSN 0958-5192 print/ISSN 1466-4399 online

q 2012 Taylor & Francis

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2011.579915

http://www.tandfonline.com

*Corresponding author. Email: anne.linna@ttl.

The International Journal of Human Resource Management,

Vol. 23, No. 7, April 2012, 13601375

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

I

N

A

S

P

-

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

(

P

E

R

I

)

]

a

t

0

2

:

0

7

0

4

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

3

perceptions by performance appraisal interviews. Longitudinal analyses are a prerequisite

for answering this fundamental question (Nathan, Mohrman and Milliman 1991;

Mushin and Byoungho 1998). This study was intended to ll this void. More specically,

the purpose of our study was to explore the effects of the experienced usefulness of

performance appraisal interviews for changes in organizational justice perceptions.

In addition, we explored whether the effects of the usefulness of performance appraisal

interviews varied by work life situation (positive or negative changes). Data on justice

perceptions were collected both before and after the performance appraisal interviews

were conducted.

Usefulness of performance appraisal interview and organizational justice

For decades, performance appraisal interview has been a widely studied and discussed

practice. It has gained the attention of researchers in human resource management

and organizational psychology. Growing concerns about organizations productivity and

effective human resources management have brought the performance appraisal practices

of the organizations into focus (Holbrook 2002).

The performance appraisal interview is dened as the formal process of evaluating

employee performance (Keeping and Levy 2000). As such, the interview constitutes a

discussion session between an employee and his or her supervisor with respect to the

employees results during the period of evaluation, focusing especially on employee

progress, aims, and needs at work. The objective of the interviews is to provide employees

with feedback on performance, to enhance communication processes between employees

and supervisors, to bring employees performances more closely in line with

organizational goals, and to facilitate the formulation of personal development plans

(Cederblom 1982; Gabris and Ihrke 2001; Pettijohn, Pettijohn and dAmico 2001).

Interviews are typically conducted once a year.

It is reasonable to assume that a performance appraisal interviewaffects two dimensions

of organizational justice. According to the self-interest model (Thibaut and Walker 1975),

individuals like to control the information used in the decision-making process to ensure or

affect the favorability of decisions. This implies that individuals value the opportunity to

voice their opinion in the decision process. This kind of voice has been a key concept in the

organizational justice literature (Folger 1977; Lind and Tyler 1988). Because the idea

behind the performance appraisal interview is to evaluate performance and plan future

actions and performance, the interview provides both supervisors and employees with an

opportunity to present their own views for consideration and to control the evaluation

process concerning their performance. Thus, the interviews can impact on the extent to

which organizational procedures include input from the affected parties, suppress bias, and

are consistently applied, accurate, correctable, and ethical (Leventhal, Karuza and Fry

1980). These are the key elements of the concept of procedural justice (Thibaut and Walker

1975; Folger 1977; Lind and Tyler 1988; Tyler 1994).

Individuals are also affected by the way in which they are treated by their supervisors.

According to the group-value model, the quality of interpersonal treatment that individuals

experience has important implications for the individuals sense of self-worth and their

experience of personal status within the group and the organization (Lind and Tyler 1988).

Because appraisal interviews occur within the context of an ongoing relationship between

the supervisor and the employee, employees have an opportunity to evaluate the quality of

the interpersonal treatment during these one-on-one transactions. When supervisors treat

employees in a constructive, truthful, and respectful manner in appraisal interviews, the

The International Journal of Human Resource Management 1361

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

I

N

A

S

P

-

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

(

P

E

R

I

)

]

a

t

0

2

:

0

7

0

4

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

3

interview can have an effect on perceptions of the interpersonal dimension of

organizational justice (Bies and Moag 1986). This dimension of treating employees with

politeness and consideration during decision making has been termed interactional justice.

In organizations, performance appraisal interview may be an important tool to improve

the justice judgments of the employees. Research has shown that justice judgments and

responses to a decision-making procedure are enhanced when those affected have an

opportunity to express their views (Lind and Tyler 1988) and have an opportunity to

express their feelings during the interview (Holbrook 1999). Thus, performance appraisal

is in agreement with the main principles of high procedural and interactional justice.

It has been suggested that organizational justice occurs differently across public and

private sectors, because public service organizations have different decision-making

procedures, work processes, and multiple and competing goals compared with private

sectors (Rainey 2009). Furthermore, public service employees are differently motivated

from their private sector counterparts (Khojasteh 1993; Karl and Sutton 1998). Indeed,

employees in public sector have been found to perceive lower level of organizational

justice than those in private sector (Kurland and Egan 1999; Heponiemi, Kuusio, Sinervo

and Elovainio 2010).

Employees reactions to performance appraisal interviews also may play an important

role. Bernardin and Beatty (1984) and Lawler (1967) have earlier proposed that

employees reactions are central with a view to the acceptance and use of the appraisal

system and also to the validity of the appraisals. More importantly, Bernardin and Beatty

(1984) suggested that employees perceptions of appraisal interviews, whether positive or

negative, are good indicators of the overall success and effectiveness of the performance

appraisal interview. In our study, we examined the perceived usefulness of performance

appraisal interviews as a potentially important determinant of justice evaluations. Of all

employee reactions to interviews, perceived usefulness has been suggested to be relatively

consistent and the least confounded (see Keeping and Levy 2000).

The perception of the usefulness of the interview has been related to employees career

discussions and goal setting (e.g. Nathan et al. 1991; Mushin and Byoungho 1998). When

supervisors discuss work goals with employees and provide important information on

employees personal growth and development needs during the interview, employees are

likely to evaluate their performance appraisal interviews as useful. Earlier studies have

shown that the perceived usefulness of the interview is associated with employee

satisfaction with the appraisal interview (Keeping and Levy 2000). Satisfaction with the

interview has been shown to affect organizational justice perceptions (e.g. Lind and Tyler

1988; Greenberg and Colquitt 2005). On this basis, we assumed that the experienced

usefulness of the interview has an association with organizational justice perceptions.

Hence, we proposed that when employees experience the interviews as useful, this would

have a positive inuence on their justice perceptions. In contrast, when employees

experience the interviews as unhelpful, we expected the impact of the interviews on justice

perceptions to be negative (cf. Folger 1977).

Hypothesis 1: Interviews that are perceived as useful improve justice perceptions

signicantly. In contrast, when the interviews are perceived as unhelpful,

the impact on justice perceptions is negative.

It has also been suggested that the effects of the usefulness of performance appraisal

interviews on justice perceptions may be inuenced by contextual factors. One such factor

is personal uncertainty. The uncertainty management model (Van den Bos and Lind 2002)

posits that when social or contextual cues make personal uncertainty a salient concern for

A. Linna et al. 1362

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

I

N

A

S

P

-

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

(

P

E

R

I

)

]

a

t

0

2

:

0

7

0

4

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

3

people, this enables people to draw on information that helps them reduce the uncertainty.

Building on and extending fairness heuristic theory (e.g. Lind 2001), the uncertainty

management model proposes that people especially rely on fairness judgments when they

are concerned about potential problems associated with social interdependence and

socially based identity processes (Van den Bos and Lind 2002). Furthermore, because fair

procedural or interactional information helps people reduce uncertainty, it is likely that

people react especially positively to fair treatment in uncertain situations. Research

ndings provide strong support for this proposition (e.g. Van den Bos and Lind 2002;

Diekmann, Barsness and Sondak 2004; Elovainio et al. 2005; Van den Bos, Poortvliet,

Maas, Miedema and Van den Ham 2005; Thau, Aquino and Wittek 2007).

We examined the continuous and rapid changes in modern work life as a potentially

important contextual determinant of personal uncertainty. According to ndings reported

by Kivimaki, Vahtera, Koskenvuo, Uutela and Pentti (1998) and Vahtera, Kivimaki, Pentti

and Theorell (2000), negative changes in the psychosocial work environment are

associated with negative changes in employees behavior. Perceived negative changes in

the work environment reect a state in which employees feel they may not be able to

sufciently control and predict events in the work environment. In this way, negative

changes at work may constitute a source of uncertainty. Therefore, we predicted that when

employees experience greater uncertainty, they are concerned about whether they are

being treated fairly (cf. Van den Bos and Lind 2002).

Hypothesis 2: When employees encounter uncertainty provoking negative changes in

work life, the perceived usefulness of performance appraisal interviews

has an especially strong inuence on employees procedural and

interactional justice judgments.

Methods

Data and sample

The data were obtained from the large, on-going, Finnish Ten Town Study exploring the

organizational behavior and health of full-time public sector employees in 10 towns in

Finland (Vahtera et al. 2000). In this longitudinal study, data were collected by

questionnaires. The baseline questionnaire study was conducted between 2000 and 2001

(Time 1). In 2004 (Time 2), a follow-up questionnaire was sent to all employees still

working in the service of the towns. In the questionnaires (Time 1 and Time 2), the

employees assessed their perceptions of organizational justice, participation in the

performance appraisal interview, the usefulness of the performance appraisal interview,

and the changes occurring in work life. Altogether 19,077 employees responded to both

questionnaires (response rate 79% at Time 2).

Because the purpose of our study was to explore the effect of the usefulness of

performance appraisal interviews on changes in the organizational justice perceptions of

employees, we excluded employees who worked in supervisory positions, had had a

performance appraisal interview at Time 1, and had changed work groups during the

follow-up. Thus, 6592 employees who did not have a supervisory position, did not attend

performance appraisal interviews at Time 1, and participated in the same work group

between Time 1 and Time 2, were included in the analysis.

Furthermore, we divided the 6592 employees into two groups based on whether they

had had a performance appraisal interview at Time 2. The rst group included employees

who had had performance appraisal interviews at Time 2 (N 3483, 53%), and the second

group included employees who had had no performance appraisal interviews at Time 2

The International Journal of Human Resource Management 1363

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

I

N

A

S

P

-

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

(

P

E

R

I

)

]

a

t

0

2

:

0

7

0

4

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

3

(N 3109, 47%). Out of the 3483 respondents who had had an interview, 14% considered

the interview to have been unhelpful, 47% rated it as neither unhelpful nor useful, and 39%

believed it to have been useful in relation to their work and personal development at work.

The group with no performance appraisal interviews served as a control group. These two

groups (interview group and no-interview group) formed the nal data set of this study.

The interview group comprised 2896 women and 587 men. The corresponding gures for

the no-interview group were 2380 and 729. The mean age for both groups was 44.7 years.

Overall, the 10 towns did not differ in terms of organizational context, tasks to be

carried out, stafng structures, or personnel characteristics (Table 1) (see also Vahtera,

Virtanen, Kivimaki and Pentti 1999; Virtanen, Nakari, Ahonen, Vahtera and Pentti 2000).

During the data collection period (between 2000 and 2004), regular performance

appraisal interviews became increasingly popular in the participating towns. The aim of

the interviews was to provide employees with feedback on their performance.

The interviews were also designed to provide employees with opportunities to present

their own views about their work and discuss their career and development opportunities.

The interviews were conducted by the direct supervisor of each employee. The supervisors

are committed to conducting annual interviews with the employees. In general, salary

discussions were not included in these interviews.

Measures

We measured procedural and interactional justice at Time 1 and Time 2 using Moormans

(1991) scales. Procedural justice was assessed on a 7-item scale (Time 1, a 0.91; Time

2, a 0.92) evaluating the degree to which the procedures at the workplace were

designed to collect the information needed for making decisions, to provide opportunities

to appeal or challenge decisions, to generate standards so that decisions could be made

with consistency, and to hear the concerns of all those affected by the decisions. Typical

scale items were Procedures are designed to hear the concerns of all those affected by the

decision and Decisions are made with consistency (the rules are the same for every

employee). The response scale was a 5-point Likert scale (1 strongly agree,

5 strongly disagree). We measured interactional justice by a 6-item measure (Time 1,

a 0.92; Time 2, a 0.93). The respondents rated their supervisors suppression of

personal biases, treatment of employees with kindness and consideration, and their

truthfulness in dealing with employees. Typical scale items were My supervisor treats

subordinates with kindness and consideration and My supervisor is able to suppress

personal biases. A 5-point Likert scale (1 strongly agree, 5 strongly disagree) was

used for the responses. Moormans scale is one of the most widely used measures in

assessments of organizational justice (e.g. Nauman and Bennett 2000; Kivimaki et al.

2003; Elovainio et al. 2005).

We measured participation in the performance appraisal interview at Time 1 and Time

2 with the question Have you had a performance appraisal interview with your supervisor

in the last 12 months? The respondents indicated their agreement on a scale of no (1) to

yes (2). Only respondents reporting no interview at Time 1 were included in the study.

If an employee responded that he or she had undergone a performance appraisal

interview at Time 2, the perceived usefulness of the interview was assessed by the question

How did you nd the appraisal interview in view of your work and personal

development? The response scale was a 3-point scale (1 unhelpful, 2 neither

unhelpful nor useful, 3 useful). Those who had had no interview during the follow-up

were formed into a fourth group for the analysis.

A. Linna et al. 1364

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

I

N

A

S

P

-

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

(

P

E

R

I

)

]

a

t

0

2

:

0

7

0

4

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

3

T

a

b

l

e

1

.

D

e

m

o

g

r

a

p

h

i

c

s

o

f

1

0

t

o

w

n

s

a

n

d

t

h

e

n

a

l

c

o

h

o

r

t

.

T

o

t

a

l

T

o

w

n

N

o

.

1

T

o

w

n

N

o

.

2

T

o

w

n

N

o

.

3

T

o

w

n

N

o

.

4

T

o

w

n

N

o

.

5

T

o

w

n

N

o

.

6

T

o

w

n

N

o

.

7

T

o

w

n

N

o

.

8

T

o

w

n

N

o

.

9

T

o

w

n

N

o

.

1

0

1

0

T

o

w

n

s

N

u

m

b

e

r

o

f

r

e

s

i

d

e

n

t

s

1

,

0

1

2

,

3

1

4

2

3

,

5

9

4

1

3

,

8

1

8

1

7

4

,

8

2

4

1

8

5

,

4

2

9

2

8

,

6

0

4

2

0

,

4

7

2

7

9

4

3

1

2

7

,

2

2

6

2

2

7

,

4

7

2

2

0

2

,

9

3

2

T

o

t

a

l

w

o

r

k

i

n

g

h

o

u

r

s

(

y

e

a

r

s

)

5

0

,

7

6

4

1

0

9

4

6

3

4

1

0

,

2

7

8

8

3

1

3

1

4

0

8

1

0

0

7

4

8

0

6

6

2

4

9

5

0

6

1

1

,

4

2

0

F

i

n

a

l

c

o

h

o

r

t

N

u

m

b

e

r

o

f

p

a

r

t

i

c

i

p

a

n

t

s

6

5

9

2

2

4

4

9

3

1

3

2

1

1

0

9

4

2

4

7

1

4

4

1

4

6

8

0

2

4

7

3

2

0

2

8

M

e

a

n

a

g

e

(

y

e

a

r

s

)

4

4

.

7

4

4

.

6

4

3

.

9

4

4

.

8

4

4

.

9

4

4

.

4

4

5

.

7

4

5

.

8

4

4

.

2

4

4

.

9

4

3

.

4

G

e

n

d

e

r

(

%

)

M

a

l

e

2

0

.

0

1

1

.

9

8

.

6

1

9

.

2

1

1

.

7

1

0

.

1

2

0

.

1

1

1

.

0

2

3

.

7

3

1

.

3

2

4

.

2

F

e

m

a

l

e

8

0

.

0

8

8

.

1

9

1

.

4

8

0

.

8

8

8

.

3

8

9

.

9

7

9

.

9

8

9

.

0

7

6

.

3

6

8

.

7

7

5

.

8

M

a

i

n

s

e

c

t

o

r

s

(

%

)

A

d

m

i

n

i

s

t

r

a

t

i

o

n

4

.

2

9

.

0

3

.

2

3

.

5

5

.

9

1

.

2

7

.

6

5

.

5

6

.

1

3

.

8

2

.

5

H

e

a

l

t

h

a

n

d

s

o

c

i

a

l

c

a

r

e

4

8

.

4

5

1

.

6

4

1

.

9

5

5

.

4

5

1

.

0

5

9

.

1

3

0

.

6

6

4

.

4

4

7

.

1

2

*

5

3

.

1

E

d

u

c

a

t

i

o

n

2

7

.

2

1

8

.

9

3

6

.

6

2

0

.

9

3

0

.

0

2

8

.

8

3

8

.

2

2

3

.

3

3

1

.

4

5

7

.

1

2

1

.

0

M

u

n

i

c

i

p

a

l

e

n

g

i

n

e

e

r

i

n

g

2

0

.

2

2

0

.

5

1

8

.

3

2

0

.

2

1

3

.

1

1

0

.

9

2

3

.

6

6

.

8

1

5

.

4

3

8

.

9

2

3

.

4

E

m

p

l

o

y

m

e

n

t

s

t

a

t

u

s

(

%

)

P

e

r

m

a

n

e

n

t

9

7

.

8

9

8

.

3

1

0

0

9

9

.

9

9

3

.

1

9

6

.

4

9

7

.

2

9

7

.

3

9

9

.

0

9

3

.

2

9

9

.

6

T

e

m

p

o

r

a

r

y

2

.

2

1

.

7

0

0

.

1

6

.

9

3

.

6

2

.

8

2

.

7

1

.

0

6

.

8

0

.

4

N

o

t

e

:

*

T

h

e

r

e

w

a

s

a

s

u

b

s

t

a

n

t

i

a

l

c

h

a

n

g

e

i

n

o

r

g

a

n

i

z

a

t

i

o

n

a

l

s

t

r

u

c

t

u

r

e

o

f

t

h

i

s

s

e

c

t

o

r

.

T

h

u

s

,

t

h

e

f

o

l

l

o

w

-

u

p

o

f

w

o

r

k

g

r

o

u

p

s

w

a

s

i

m

p

o

s

s

i

b

l

e

.

The International Journal of Human Resource Management 1365

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

I

N

A

S

P

-

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

(

P

E

R

I

)

]

a

t

0

2

:

0

7

0

4

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

3

We assessed changes in work life by the question If you think of all the changes that

have taken place at work during the last 12 months, how you would describe them?

The response scale was a 7-point Likert scale (1 mostly negative, 7 mostly positive).

For the gures, the response scale was divided into a 3-point scale (13 as a negative, 4

as an in between, and 57 as a positive).

Control variables gender (1 female, 2 male), age (in years), socioeconomic

status (1 white-collar, 2 blue-collar), and job demands were measured at Time 1 and

a number of employees in a work group (1 # 20, 2 2050, 3 $ 50) measured at Time 2

were entered as control variables in the analysis. Each participants work group was

identied from the employers records. Using employers work group registers kept for

administrative purposes, we selected work groups at the lowest organizational level. These

are functional work groups that are typically at a single location (e.g. a kindergarten, a

school, or a hospital ward). The number of work groups was 1291. The number of

employees in the work groups ranged from 1 to 128, with a mean size of 22.14

(SD 32.62) employees. Job demands were measured on a 5-item scale (Time 1,

a 0.81) from Karaseks Job Content Questionnaire (Karasek et al. 1998). Typical scale

items were I have to work very fast and I am often pressured to work overtime.

The response scale was a 5-point Likert scale (1 strongly agree, 5 strongly disagree).

Questions about job demands assessed the employees workload and work pace.

Statistical analyses

First, we analyzed changes in procedural and interactional justice perceptions in the

interview and no-interview groups between Time 1 and Time 2 in general. We conducted a

repeated analysis of variance that took into account the control variables (gender, age,

socioeconomic status, number of employees in the work group, and job demands), the

interview group variable (interview vs. no-interview), time (Time 1 and Time 2), and the

interaction between time and group.

Masterson, Lewis, Goldman and Taylor (2000) have suggested that the perceptions of

justice among other work group members may shape a persons own perception of justice

(see also Folger, Roseneld, Grove and Corkran 1979). When individuals work together

and interact with one another, they may adopt shared perceptions of organizational

practices, procedures, and equity. In other words, employees are nested in clusters

(work groups), and these two levels of hierarchy (employee and work group level) can

introduce an additional source of variability and correlation.

Multilevel regression analyses were used to test the effects of usefulness of the

interview on justice perceptions. Multilevel regression analysis enables the consideration

of both individual-level (within-group, Level 1) and work group-level (between-group,

Level 2) effects on justice perceptions (Bryk and Raudenbush 1992). Specically,

multilevel regression analysis considers statistical dependencies of observations within

groups and differences across groups and provides less biased estimates for standard errors

of regression coefcients. All statistical analyses were performed with the help of SAS 9.1.

statistical software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA), applying the Mixed procedure.

The viability of using multilevel modeling to test our hypothesis was checked before

the analyses. We calculated intra-class correlation (ICC

1

) of a random intercept model

using the equation t

00

/(t

00

s

2

), where t

00

is between-group variance in the dependent

variable and s

2

is within-group variance in the dependent variable (Bryk and Raudenbush

1992). This analysis estimated the degree of variance in the individual-level dependent

variable that can be explained by group level properties. The ICC

1

indicated that 10% of

A. Linna et al. 1366

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

I

N

A

S

P

-

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

(

P

E

R

I

)

]

a

t

0

2

:

0

7

0

4

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

3

the variance in procedural justice and 18% of the variance in interactional justice occurred

between the groups. In addition to examining the homogeneity of justice perceptions

within the work groups, we calculated the inter-rater agreement index (r

wg

). This index

indicates the consensus among employees within a single work group with respect to a

justice variable. Across the 1291 work groups, a mean r

wg

of 0.81 was calculated for

procedural justice, whereas the value for interactional justice was 0.80. These values were

above the conventionally acceptable r

wg

value of 0.70 (James, Demaree and Wolf 1993).

On the basis of these results, we concluded that justice perceptions varied between the

work groups and that there was strong average within-group agreement. The use of

multilevel regression analysis was therefore justied.

Second, to explore the changes in justice perceptions, we calculated the change score

in procedural and interactional justice by deducting the Time 2 score from the Time 1

score. We did not adjust the Time 1 justice score, as change-score analyses without

baseline adjustment are more likely to provide unbiased causal effect estimates while

baseline adjusted estimates are biased (Glymour, Weune, Berkman, Kawachi and Robins

2005).

Third, to test the association between the usefulness of performance appraisal

interviews and changes in justice perceptions (Hypothesis 1), and the effect of interaction

between the usefulness of performance appraisal interviews and changes in work life on

justice perceptions (Hypothesis 2), we constructed a multilevel model that took into

account the effects of control variables (gender, age, socioeconomic status, number of

employees in the work group, and job demands) and the group variable (work group of a

respondent). Because of the size of the data set, we used p # 0.001 to indicate statistical

signicance.

Results

Table 2 presents the correlations among all study variables for interview and no-interview

groups. The 4-year Time 1Time 2 correlation coefcients for procedural and

interactional justice between the interview and no-interview groups were similar (rs

between 0.42 and 0.51). The perceptions of procedural and interactional justice were

moderately interrelated in both groups (rs between 0.49 and 0.53). There was a slight

association between changes in work life and justice perceptions (rs ,0.39) and a weak

connection between the usefulness of the interviews and Time 1 justice perceptions

(r , 0.21), whereas the association was moderate for Time 2 justice perceptions

(rs 0.34 and 0.48).

Performance appraisal interviews were more common among the female, white-collar

employees and among those working in small work groups than they were among other

types of employees ( ps , 0.001, Table 3). Age ( p 0.94) and job demands ( p 0.73)

were similar between the interview and no-interview groups. Changes in work life were

perceived as slightly more negative among the no-interview group (M 3.9, SD 0.03)

than in the interview group (M 4.1, SD 0.04). The perceptions of procedural and

interactional justice at Time 1 did not signicantly and meaningfully differ between the

interview group and the no-interview group (for procedural justice, F(1,6303) 3.52,

p 0.06; for interactional justice F(1,6494) 2.59, p 0.11).

We rst analyzed changes in procedural and interactional justice perceptions in the

interview and no-interview groups between Time 1 and Time 2. After controlling for

gender, age, socioeconomic status, number of employees in the work group, and job

demands, there was a signicant interaction between time (Time 1 and Time 2) and the

The International Journal of Human Resource Management 1367

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

I

N

A

S

P

-

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

(

P

E

R

I

)

]

a

t

0

2

:

0

7

0

4

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

3

T

a

b

l

e

2

.

C

o

r

r

e

l

a

t

i

o

n

s

a

m

o

n

g

s

t

u

d

y

v

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

s

f

o

r

i

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

(

r

i

g

h

t

)

a

n

d

n

o

-

i

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

g

r

o

u

p

s

(

l

e

f

t

)

.

I

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

g

r

o

u

p

V

a

r

i

a

b

l

e

s

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1

0

1

1

N

o

-

i

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

g

r

o

u

p

1

G

e

n

d

e

r

0

.

2

4

*

2

0

.

0

0

2

0

.

0

2

2

0

.

1

0

*

2

0

.

0

7

*

2

0

.

0

7

*

2

0

.

0

4

2

0

.

0

5

2

0

.

0

2

2

0

.

0

4

2

S

o

c

i

o

e

c

o

n

o

m

i

c

s

t

a

t

u

s

0

.

3

6

*

0

.

1

2

*

0

.

0

4

2

0

.

0

0

2

0

.

0

2

2

0

.

0

9

*

2

0

.

0

3

2

0

.

0

4

2

0

.

0

5

2

0

.

0

8

*

3

S

i

z

e

o

f

w

o

r

k

g

r

o

u

p

0

.

0

3

0

.

1

3

*

0

.

0

4

0

.

0

3

0

.

0

0

0

.

0

1

2

0

.

0

5

2

0

.

0

2

0

.

0

1

2

0

.

0

1

4

A

g

e

2

0

.

0

2

0

.

0

5

0

.

0

4

0

.

0

0

0

.

0

3

0

.

0

0

0

.

0

5

0

.

1

0

*

2

0

.

0

1

0

.

0

2

5

J

o

b

d

e

m

a

n

d

s

2

0

.

1

1

*

2

0

.

0

7

*

0

.

0

2

0

.

0

2

2

0

.

1

5

2

0

.

0

7

*

2

0

.

2

1

*

2

0

.

1

6

*

2

0

.

1

9

*

2

0

.

1

3

*

6

C

h

a

n

g

e

s

i

n

w

o

r

k

l

i

f

e

2

0

.

0

7

*

2

0

.

0

6

*

2

0

.

0

0

2

0

.

0

1

2

0

.

1

5

*

0

.

2

5

*

0

.

1

8

*

0

.

3

3

*

0

.

1

1

*

0

.

3

2

*

7

U

s

e

f

u

l

n

e

s

s

o

f

i

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

0

.

2

0

*

0

.

3

4

*

0

.

2

1

*

0

.

4

8

*

8

P

r

o

c

e

d

u

r

a

l

j

u

s

t

i

c

e

(

T

i

m

e

1

)

2

0

.

0

5

2

0

.

0

8

*

2

0

.

0

2

0

.

0

0

2

0

.

1

8

*

0

.

2

4

*

0

.

4

8

*

0

.

5

0

*

0

.

3

1

*

9

P

r

o

c

e

d

u

r

a

l

j

u

s

t

i

c

e

(

T

i

m

e

2

)

2

0

.

0

4

2

0

.

0

8

*

2

0

.

0

2

0

.

0

2

2

0

.

1

3

*

0

.

3

9

*

0

.

5

1

*

0

.

2

9

*

0

.

4

9

*

1

0

I

n

t

e

r

a

c

t

i

o

n

a

l

j

u

s

t

i

c

e

(

T

i

m

e

1

)

2

0

.

0

4

2

0

.

0

9

*

0

.

0

3

2

0

.

0

3

2

0

.

1

6

*

0

.

1

7

*

0

.

5

3

*

0

.

3

4

*

0

.

4

2

*

1

1

I

n

t

e

r

a

c

t

i

o

n

a

l

j

u

s

t

i

c

e

(

T

i

m

e

2

)

2

0

.

0

6

*

2

0

.

1

0

*

0

.

0

2

0

.

0

0

2

0

.

0

7

*

0

.

3

6

*

0

.

3

5

*

0

.

5

3

*

0

.

4

9

*

N

o

t

e

:

F

o

r

i

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

g

r

o

u

p

,

N

3

4

8

3

;

f

o

r

n

o

-

i

n

t

e

r

v

i

e

w

g

r

o

u

p

,

N

3

1

0

9

.

*

p

,

0

.

0

0

1

.

A. Linna et al. 1368

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

I

N

A

S

P

-

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

(

P

E

R

I

)

]

a

t

0

2

:

0

7

0

4

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

3

interview groups (interview vs. no-interview). In the no-interview group, negative changes

in procedural and interactional justice were observable between Time 1 and Time 2,

whereas in the interview group, there was an increase in the mean of procedural and

interactional justice (Table 3).

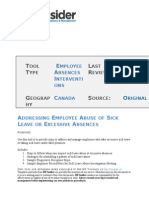

Figure 1 shows the results of the multilevel analyses conducted to test our rst

hypothesis proposing that the usefulness of performance appraisal interviews is associated

with changes in procedural justice and interactional justice perceptions. After controlling

for gender, age, socioeconomic status, number of employees in the work group, and job

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

Unhelpful Neither/nor Useful

No interview

M

e

a

n

c

h

a

n

g

e

(

S

E

)

Procedural justice

Interactional justice

Performance appraisal interview

Figure 1. Change in procedural and interactional justice perceptions and usefulness of performance

appraisal interview.

Table 3. Characteristics of the interview group and no-interview group.

a

Interview group No-interview group

Variables Time N % or M (SD) N % or M (SD) p

b

Gender 1

Female 2896 55 2380 45

*

Male 587 45 729 55

Socioeconomic status 1

White-collar 2839 56 2267 44

*

Blue-collar 644 43 842 57

Size of work group 2

, 20 2851 56 2281 44

*

2050 372 42 511 58

. 50 260 45 317 55

Age 1 3483 44.7 (7.9) 3109 44.7 (8.1) ns

Job demands 1 3459 3.27 (0.83) 3092 3.27 (0.81) ns

Changes in work life

c

2 4.08 (0.04) 3.92 (0.03)

*

Procedural justice

c,d

1 2.99 (0.02) 2.95 (0.02) ns

Procedural justice

c

2 3.05 (0.02) 2.89 (0.02)

*

Interactional justice

c,e

1 3.52 (0.02) 3.48 (0.02) ns

Interactional justice

c

2 3.65 (0.02) 3.41 (0.02)

*

Notes:

*

p , 0.001.

a

For interview group, N 3483; for no-interview group, N 3109.

b

x

2

-test for classic variables, t-test for continuous variables.

c

Adjusted for gender, age, socioeconomic status, size of work group, and job demands.

d

Procedural justice: interaction group time, F(1,6075) 26.68, p , 0.001.

e

Interactional justice: interaction group time, F(1,6426) 63.86, p , 0.001.

The International Journal of Human Resource Management 1369

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

I

N

A

S

P

-

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

(

P

E

R

I

)

]

a

t

0

2

:

0

7

0

4

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

3

demands, the usefulness of the interview was signicantly associated with a change in

organizational justice, being stronger for interactional justice, F(3,5151) 90.70,

p , 0.001, than for procedural justice, F(3,4822) 34.80, p , 0.001.

In sum, among the employees who rated the interview as unhelpful, procedural and

interactional justice evaluations deteriorated. This deterioration was even stronger than

among those who did not have an interview during the follow-up. For the employees with

mixed feelings about the usefulness of such interviews, no changes in justice perceptions

were observed. Only an interview perceived as useful was associated with signicant

improvement in organizational justice perceptions.

We also tested whether the combined effects of changes in work life and the usefulness

of performance appraisal interviews inuence justice perceptions (Hypothesis 2).

Regarding the usefulness score, the interaction was signicant with respect to interactional

justice perceptions, F(3,4948) 4.76, p 0.003, but not with procedural justice

perceptions. As shown in Figure 2, unhelpful interviews were associated with deteriorated

perceptions of interactional justice in the case of negative changes in work life, but had no

effect in the case of positive changes. Useful interviews improved interactional justice

perceptions regardless of the changes in work life.

Discussion

The purpose of this longitudinal study was to explore the effect of the experienced

usefulness of the performance appraisal interviews on organizational justice perceptions.

We found that if interviews were not used, no changes in justice perceptions were

observed during the 4-year follow-up. We also found that when interviews had been

conducted, this had an effect on justice perceptions. However, the changes in justice

perceptions were dependent on perceived usefulness of the interview. Perceptions of

procedural and interactional justice improved among those who had had a useful

interview, whereas unhelpful interviews were associated with deterioration in perceptions

of procedural and interactional justice. For employees with mixed feelings about the

usefulness of the interviews, no changes in justice perceptions were observed. Our results

remained the same, even when we repeated the analyses using an aggregated score instead

Changes in work life

0.6

0.4

0.2

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

Unhelpful Neither/nor Useful

No interview

M

e

a

n

c

h

a

n

g

e

(

S

E

)

Negative

In-between

Positive

Performance appraisal interview

Figure 2. Change in interactional justice perceptions predicted by interaction between usefulness

of performance appraisal interview and changes in work life.

A. Linna et al. 1370

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

I

N

A

S

P

-

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

(

P

E

R

I

)

]

a

t

0

2

:

0

7

0

4

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

3

of a self-reported score as a measure of usefulness (data not shown). Thus, common

method bias due to response style is an unlikely explanation to our ndings.

Our second aim was to explore the impact of the combined effects of changes in work

life and experienced usefulness of performance appraisal interviews on justice

perceptions. Our results suggest that the consequences of appraisal interviews may, in

part, depend on the changes employees experience within the work life situation.

In general, negative changes in work life were associated with a decrease in interactional

justice. Importantly, those who reported negative changes in work life and had useful

interview with supervisors still showed improved interactional justice perceptions.

However, if employees experienced the interviews as unhelpful, interactional justice

perceptions deteriorated dramatically. It is also likely that treatment by supervisors

during uncontrollable situations may be more important than process control over decision

making for employees, because the interaction between changes in work life and the

usefulness of the interview was signicantly associated only with interactional justice

perceptions.

How can justice perceptions be improved only by a useful interview? When the

supervisors discuss their careers and personal development in their work with the

employees and provide career and development information about what it takes to be

successful in the organization, the employees may experience the interviews as useful

(Nathan et al. 1991). In addition, perceived usefulness has been associated with a situation

in which the supervisor has set clear goals for the employees and ensured that the goals are

understood and that the employees fully grasp the relationship between their own work and

the goals (Mushin and Byoungho 1998). Our ndings are in agreement with the results of

earlier studies suggesting that employees reactions are good indicators of the success of

the performance appraisal interviews (e.g. Bernardin and Beatty 1984). Furthermore, our

ndings give some answer to the fundamental open question do appraisal interviews

actually change employees attitudes (see Nathan et al. 1991). Our ndings support the

suggestion that poorly conducted performance appraisal interviews may negatively

inuence employees work attitudes, e.g. job satisfaction and justice perceptions

(e.g. Greller 1978; Korsgaard and Roberson 1995; Holbrook 1999). Thus, the content of the

performance appraisal interview has an important role in changing employees attitudes.

Our results give support to the uncertainty management model for justice perceptions

(Van den Bos and Lind 2002). According to the uncertainty management model, people

have a fundamental need to feel certain about their world and their place in it. Uncertainty

can be threatening, and people generally feel a need either to eliminate uncertainty or to

nd some way to make it tolerable and cognitively manageable, for example by evaluating

organizational justice. The uncertainty management model (Van den Bos and Lind 2002)

proposes that stronger fair process effects can be expected to occur when people do not

have direct information about an authoritys trustworthiness or are, in general, in

uncontrolled or unpredictable situations. In accordance with this reasoning, we showed

that justice effects related to the usefulness of performance appraisal interviews were

strongest when people were confronted with unpredictable or uncontrollable situations in

the form of major changes in work life.

The main strengths of our study were its large scale with over 6500 public sector

employees working in more than 1200 work groups, all of whom remained in the same

work groups throughout the whole study; a before and after casecontrol design with no

appraisal interview at baseline and a 4-year follow-up; the ability to repeat analysis with

aggregated usefulness of the interview; and the possibility to take into account several

control variables. Finally, because the data were hierarchically organized, we were able to

The International Journal of Human Resource Management 1371

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

I

N

A

S

P

-

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

(

P

E

R

I

)

]

a

t

0

2

:

0

7

0

4

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

3

use multilevel modeling. This analysis enables the consideration of each employees work

group when testing the inuence of usefulness of the performance appraisal interviews on

the justice perceptions of employees. Thus, our study provides perhaps the best data

available for examining the possibilities to enhance justice within organizations by means

of experienced usefulness of the appraisal interviews and for showing how justice

perceptions are affected by contextual factors, such as negative or positive changes in

work life.

There are some limitations to this study. First, the correlation between Moormans

(1991) measure of procedural and interactional justice was moderate (rs between 0.48 and

0.53), and therefore, these two variables shared about 25% of their variance. It is likely

that perceived changes in the fairness of treatment in the supervisor employee

relationship inuence perceptions of justice in overall organizational decision-making

procedures. Recently, Cropanzano, Prehar and Chen (2002) have argued in favor of

separating procedural and interactional justice. Second, the usefulness of the interview and

the changes in work life were assessed by single-item measures.

Third, we were not able to measure the nature of the feedback (positive or negative) in

the performance appraisal interview or employees perceptions of the appraisal

procedures. It is likely that positive feedback in the performance appraisal interviews or

positive appraisal of the procedures would have a different impact on employees

reactions to the interview than would negative feedback or appraisal.

Fourth, there were signicant differences between the no-interview group and the

interview group as to demographic characteristics. It is well known that performance

appraisal interviews are not random in relation to work groups and jobs (Holbrook 2002).

Fifth, we do not know the exact year when appraisal interviews were applied for the

rst time during the follow-up. After the baseline questionnaire, an intensive transition to

conducting performance appraisal interviews yearly had begun in municipalities, and this

transition was still going on in 2004.

Finally, we investigated the perceptions of organizational justice in the Finnish work

life context. It should be noted that the employment conditions in Finland are relatively

similar to those in other EU countries (Gallie 2000). Thus, our ndings are not necessarily

restricted to the Finnish context only. However, more research in different contexts is

needed.

From a practical perspective, the results of our study show the importance of

conducting useful performance appraisal interviews. Useful interviews seem to be a

crucial element in the perception of fair management and fair organizations. Useful

appraisal interviews are likely to enhance mutual relationships and the functioning of the

work group. The results of our study suggest that it is not enough for organizations to see to

it that performance appraisal interviews are conducted. On the contrary, it appears that the

supervisors should strive to perform well when they interview their employees. Previous

studies have shown that training can improve supervisors capabilities to conduct useful

performance appraisal interviews (e.g. Taylor et al. 1995).

Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge that the absence of performance appraisal

interview as an organizational tool can be risky for organizations. Employees who do not

receive feedback about their work and have no opportunity to have a voice may believe

that their organization is unfair. Almost half of the respondents had not had a performance

appraisal interview at all during the year of the follow-up. This omission could have been

due to supervisors fears of conducting such interviews (Dickinson 1993). However, in our

data, no changes in organizational justice were observed among those who had had no

appraisal interview during the follow-up.

A. Linna et al. 1372

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

I

N

A

S

P

-

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

(

P

E

R

I

)

]

a

t

0

2

:

0

7

0

4

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

3

Future research is needed to evaluate how long the changes in justice perceptions

following the interview last and to identify factors contributing to the perceived usefulness

of the performance appraisal interview. Because the perceptions of justice among co-

workers may shape an employees own perception of justice (Masterson et al. 2000), the

hierarchical structure of an organization needs to be taken into account. If this structure is

ignored in studies of organizational justice and its consequences, there is a risk that the

organizational behavior of the employees will be misunderstood.

References

Bernardin, H.J., and Beatty, R.W. (1984), Performance Appraisal: Assessing Human Performance

at Work, Boston, MA: Kent.

Bies, R.J., and Moag, J.S. (1986), Interactional Justice: Communication Criteria of Fairness,

in Research on Negotiation in Organizations, eds. R.J. Lewicki, B.H. Sheppard and

M.H. Bazerman, Greenwich, CT: JAI Press, pp. 4355.

Bryk, A.S., and Raudenbush, S.W. (1992), Hierarchical Linear Models: Applications and Data

Analysis Methods, Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Cederblom, D. (1982), The Performance Appraisal Interview: A Review, Implications, and

Suggestions, Academy of Management Review, 7, 219227.

Cole, N.D., and Latham, G.P. (1997), Effects of Training in Procedural Justice on Perceptions of

Disciplinary Fairness by Unionized Employees and Disciplinary Subject Matter Experts,

Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 699705.

Colquitt, J.A., Conlon, D.E., Wesson, M.J., Porter, C.O.L.H., and Ng, K.Y. (2001), Justice at the

Millennium: A Meta-analytic Review of 25 Years of Organizational Justice Research,

Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 425445.

Cropanzano, R., Byrne, Z.S., Bobocel, D.R., and Rupp, D.E. (2001), Moral Virtues, Fairness

Heuristics, Social Entities, and Other Denizens of Organizational Justice, Journal of Vocational

Behavior, 58, 164209.

Cropanzano, R., Prehar, C.A., and Chen, P.Y. (2002), Using Social Exchange Theory to Distinguish

Procedural from Interactional Justice, Group and Organization Management, 27, 324351.

Dickinson, T.L. (1993), Attitudes about Performance Appraisal, in Personnel Selection and

Assessment: Individual and Organizational Perspectives, eds. H. Schuler, J.L. Farr and

M. Smith, Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, pp. 141162.

Diekmann, K.A., Barsness, Z.I., and Sondak, H. (2004), Uncertainty, Fairness Perceptions, and Job

Satisfaction: A Field Study, Social Justice Research, 17, 237255.

Elovainio, M., Van den Bos, K., Linna, A., Kivimaki, M., Ala-Mursula, L., Pentti, J., and Vahtera, J.

(2005), Combined Effects of Uncertainty and Organizational Justice on Employee Health:

Testing the Uncertainty Management Model of Fairness Judgments among Finnish Public Sector

Employees, Social Science and Medicine, 61, 25012512.

Folger, R. (1977), Distributive and Procedural Justice: Combined Impact of Voice and

Improvement of Experienced Inequity, Journal of Personal Social Psychology, 35, 108119.

Folger, R., and Konovsky, M.A. (1989), Effects of Procedural and Distributive Justice on Reactions

to Pay Raise Decisions, Academy of Management Journal, 32, 115130.

Folger, R., Roseneld, D., Grove, J., and Corkran, L. (1979), Effects of Voice and Peer Opinions

on Responses to Inequity, Journal of Personal Social Psychology, 37, 22532261.

Gabris, G.T., and Ihrke, D.M. (2001), Does Performance Appraisal Contribute to Heightened

Levels of Employee Burnout? The Results of One Study, Public Personal Management, 30,

157172.

Gallie, D. (2000), The Quality of Working Life: Is Scandinavia Different? Estudios, Working

Paper 154.

Glymour, M.M., Weune, J., Berkman, L.F., Kawachi, I., and Robins, J.M. (2005), When Is Baseline

Adjustment Useful in Analyses of Change? An Example with Education and Cognitive Change,

American Journal of Epidemiology, 162, 267278.

Greenberg, J. (2010), Organizational Injustice as an Occupational Health Risk, Academy of

Management Annals, 4, 205243.

Greenberg, J., and Colquitt, J.A. (2005), Handbook of Organizational Justice: Fundamental

Questions about Fairness in the Workplace, Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

The International Journal of Human Resource Management 1373

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

b

y

[

I

N

A

S

P

-

P

a

k

i

s

t

a

n

(

P

E

R

I

)

]

a

t

0

2

:

0

7

0

4

N

o

v

e

m

b

e

r

2

0

1

3

Greller, M.M. (1978), The Nature of Subordinate Participation in the Appraisal Interview,

Academy of Management Journal, 21, 646658.

Heponiemi, T., Kuusio, H., Sinervo, T., and Elovainio, M. (2010), Job Attitudes and Well-Being

among Public vs. Private Psysicians: Organizational Justice and Job Control as Mediators,

European Journal of Public Health, 4, 16.

Holbrook, R.L. Jr (1999), Managing Reactions to Performance Appraisal: The Inuence of Multiple

Justice Mechanisms, Social Justice Research, 12, 205221.

Holbrook, R.L. Jr (2002), Contact Points and Flash Points: Conceptualizing the Use of Justice

Mechanisms in the Performance Appraisal Interview, Human Resource Management Review,

12, 101123.

James, L.R., Demaree, R.G., and Wolf, G. (1993), Estimating Within-Group Interrater Reliability

With and Without Response Bias, Journal of Applied Psychology, 69, 8598.

Karasek, R.A., Brisson, C., Kawakami, N., Houtman, I., Bongers, P., and Amick, B. (1998), The Job

Content Questionnaire (JCQ): An Instrument for Internationally Comparative Assessments of

Psychological Job Characteristics, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 3, 322355.

Karl, K.A., and Sutton, C.L. (1998), Job Values in Todays Workforce: A Comparison of Public and

Private Sector Employees, Public Personnel Management, 27, 515527.

Keeping, L.M., and Levy, P.E. (2000), Performance Appraisal Reactions: Measurement, Modeling,

and Method Bias, Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 708723.

Khojasteh, M. (1993), Motivating the Private vs. Public Sector Managers, Public Personnel

Management, 22, 391401.

Kivimaki, M., Elovainio, M., Vahtera, J., Virtanen, M., and Stansfeld, S.A. (2003), Association

Between Organisational Inequity and Incidence of Psychiatric Disorders in Female Employees,

Psychological Medicine, 33, 319326.

Kivimaki, M., Vahtera, J., Koskenvuo, M., Uutela, A., and Pentti, J. (1998), Response of Hostile

Individuals to Stressful Change in Their Working Lives: Test of a Psychosocial Vulnerability

Model, Psychological Medicine, 28, 903913.

Konovsky, M.A. (2000), Understanding Procedural Justice and Its Impact on Business

Organizations, Journal of Management, 26, 489511.

Korsgaard, M.A., and Roberson, L. (1995), Procedural Justice in Performance Evaluation: The Role

of Instrumental and Non-instrumental Voice in Performance Appraisal Discussions, Journal of

Management, 21, 657669.

Kouvonen, A., Vahtera, J., Elovainio, M., Cox, S.J., Cox, T., Linna, A., Virtanen, M., and Kivimaki,

M. (2007), Organisational Justice and Smoking: The Finnish Public Sector Study, Journal of

Epidemiology and Community Health, 61, 427433.

Kurland, N.P., and Egan, T.D. (1999), Public v. Private Perceptions of Formalization, Outcomes,

and Justice, Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 3, 437458.

Lawler, E.E. (1967), The Multitrait-Multirate Approach to Measuring Managerial Job

Performance, Journal of Applied Psychology, 51, 369381.

Leventhal, G.S., Karuza, J., and Fry, W.R. (1980), Beyond Fairness: A Theory of Allocation

Preferences, in Justice and Social Interaction, ed. G. Mikula, New York: Springer-Verlag,

pp. 167218.

Lind, E.A. (2001), Fairness Heuristic Theory: Justice Judgments as Pivotal Cognitions in

Organizational Relations, in Advances in Organizational Behavior, eds. J. Greenberg and

R. Cropanzano, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, pp. 5688.

Lind, E.A., and Tyler, T. (1988), The Social Psychology of Procedural Justice, New York: Plenum.

Masterson, S.S., Lewis, K., Goldman, B.M., and Taylor, M.S. (2000), Integrating Justice and Social

Exchange: The Differing Effects of Fair Procedures and Treatment on Work Relationships,

Academy of Management Journal, 43, 738748.

McFarlin, D.B., and Sweeney, P.D. (1992), Distributive and Procedural Justice as Predictors of

Satisfaction with Personal and Organizational Outcomes, Academy of Management Journal, 35,

626637.

Moorman, R.H. (1991), Relationship Between Organizational Justice and Organizational