Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Disarmament Times Summer 2013

Disarmament Times Summer 2013

Uploaded by

DTEeditorCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5833)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Horn of Africa As A Security ComplexDocument18 pagesThe Horn of Africa As A Security ComplexIbrahim Abdi Geele100% (1)

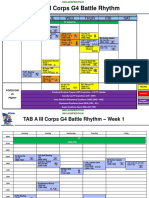

- Battle Rhythm OPT - G4 Slides (19 AUG 14)Document18 pagesBattle Rhythm OPT - G4 Slides (19 AUG 14)Stephen SmithNo ratings yet

- Jose Ignacio Paua - His ExploitsDocument22 pagesJose Ignacio Paua - His ExploitsAnsam Lee100% (1)

- 1 - Microsoft Office Activities and ProjectsDocument137 pages1 - Microsoft Office Activities and Projectsmjae18No ratings yet

- Pendragon Berber & Saracen Characters in PendragonDocument16 pagesPendragon Berber & Saracen Characters in PendragonLeonardo Correia de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Regs Gunpowder MagazinesDocument24 pagesRegs Gunpowder MagazinesAuldmonNo ratings yet

- Internation Youth Summit For Nuclear Abolition Creates MomentumDocument2 pagesInternation Youth Summit For Nuclear Abolition Creates MomentumDTEeditorNo ratings yet

- 70 Years of Making Nukes: The Lowdown On U.S. ProductionDocument4 pages70 Years of Making Nukes: The Lowdown On U.S. ProductionDTEeditorNo ratings yet

- The Rise of The Drones by M McGivernDocument3 pagesThe Rise of The Drones by M McGivernDTEeditorNo ratings yet

- NGO Spotlight - Loretto Goes To WashingtonDocument5 pagesNGO Spotlight - Loretto Goes To WashingtonDTEeditorNo ratings yet

- New Verification Report Series From NTIDocument2 pagesNew Verification Report Series From NTIDTEeditorNo ratings yet

- A Message From NGOCDPS President Bruce KnottsDocument1 pageA Message From NGOCDPS President Bruce KnottsDTEeditorNo ratings yet

- 2023 Murillo Sandoval Et Al - The Post-Conflict Expansion of Coca Farming and Illicit Cattle Ranching in ColombiaDocument10 pages2023 Murillo Sandoval Et Al - The Post-Conflict Expansion of Coca Farming and Illicit Cattle Ranching in ColombiaJuan Antonio SamperNo ratings yet

- Helen of TroyDocument6 pagesHelen of TroyFernanda ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Project B06Document6 pagesProject B06Melanie JerónimoNo ratings yet

- Enigma and The U-Boat War: Home MenuDocument3 pagesEnigma and The U-Boat War: Home MenuNewvovNo ratings yet

- Migration and Refugee Crisis Faith On The Move July 10 2016Document37 pagesMigration and Refugee Crisis Faith On The Move July 10 2016api-324470913No ratings yet

- Script For Gerph ReportingDocument5 pagesScript For Gerph ReportingDelmar Laurence BergadoNo ratings yet

- Fulltext PDFDocument318 pagesFulltext PDFOmar Al-Ta'eeNo ratings yet

- Breaking The Tether of Fuel 2007Document5 pagesBreaking The Tether of Fuel 2007j_s_fuchsNo ratings yet

- Military - British Army - Hats & CapsDocument61 pagesMilitary - British Army - Hats & CapsThe 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center100% (4)

- 2021 Buyer'S Guide: GlockDocument20 pages2021 Buyer'S Guide: GlockChris HaerringerNo ratings yet

- Modern World HistoryDocument6 pagesModern World Historyapi-276267345No ratings yet

- Risk Battlefield Rogue RulesDocument8 pagesRisk Battlefield Rogue RulesMichael HuynhNo ratings yet

- Quatre Bras 1815Document5 pagesQuatre Bras 1815Peter MunnNo ratings yet

- 0803232446Document641 pages0803232446Bojan KanjaNo ratings yet

- Manipulation of The MediaDocument8 pagesManipulation of The MediaAbigail AnguianoNo ratings yet

- The Unnatural History of Tolkien's OrcsDocument12 pagesThe Unnatural History of Tolkien's OrcsanctrooperNo ratings yet

- Youth Organizations in Great BritainDocument7 pagesYouth Organizations in Great BritainLara FalkonNo ratings yet

- Aikido WordsDocument19 pagesAikido Wordsamaria1No ratings yet

- Cyber TerrorismDocument22 pagesCyber TerrorismgauthamsagarNo ratings yet

- Republic of Korea - Position PaperDocument2 pagesRepublic of Korea - Position PaperihabNo ratings yet

- The Effects of A Nuclear Bomb PDFDocument2 pagesThe Effects of A Nuclear Bomb PDFThe Dangerous OneNo ratings yet

- Norway and The Northern Front: Wartime ProspectsDocument46 pagesNorway and The Northern Front: Wartime ProspectsAlaric SerraNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument353 pagesPDFachysfNo ratings yet

- Declaration of Independence PDFDocument2 pagesDeclaration of Independence PDFEmma Maria Fernando0% (1)

Disarmament Times Summer 2013

Disarmament Times Summer 2013

Uploaded by

DTEeditorCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Disarmament Times Summer 2013

Disarmament Times Summer 2013

Uploaded by

DTEeditorCopyright:

Available Formats

News & Anal ysi s Al l i son Pyt l ak and El i zabet h Ki rkham

Disarmament Times

P u b l i s h e d b y t h e N G O C o m m i t t e e o n D i s a r m a m e n t , P e a c e a n d S e c u r i t y

Summer 2013 Vol ume 36 Number 2

Ar ms Trade Treat y Approved

N G O C o m m i t e e o n D i s a r m a m e n t ,

P e a c e a n d S e c u r i t y

7 7 7 U N P l a z a , 3 B , N e w Y o r k N Y 1 0 0 1 7

F i r s t C l a s s

U S P o s t a g e

P A I D

N e w Y o r k N Y

P e r m i t # 6 3 3

I n s i d e T h i s I s s u e

Continued on page 2.

UNHCR/A. Solumsmoen

UNHCR Del i v er s Humani t ar i an Ai d t o Sy r i ans

The U.N. refugee agency at the end of January completed a frst delivery of winter emergency

relief to the Azzas area of northern Syria, where thousands of internally displaced people are

living in makeshif camps, as well as to the Kerama camp. See story pages 3-4.

While imperfect, the ATT nevertheless sets an important baseline for global acton

to control the conventonal arms trade and represents a signifcant improvement on the

draf text that was on the table at the end of the July 2012 ATT Diplomatc Conference.

Overall, the Treaty benefts from greater clarity and has been strengthened in some key

areas, including:

Revision of clauses that would have subordinated the ATT to existng or future agree-

ments, which would have allowed states to ignore the ATT when exportng arms as part

of defense co-operaton agreements.

Inserton of a new artcle (11) on diversion, which requires states to take a range of

measures to prevent diversion of arms transfers.

Improved amendment provisions so that, instead of requiring consensus, decisions

on amendment can be made by a majority at three-yearly intervals, from six years

afer the Treaty enters into force.

Lowering of the threshold for entry into force from 65 state ratfcatons to 50.

Deleton of an artcle on relatons with states that have not ratfed the Treaty, which

raised the prospect that weaker controls could be applied to states that are not party to

the Treaty than are applied to its members.

The export risk assessment (Artcle 7) has also been strengthened. Alongside re-

quirements that states consider the efects weapons transfers are likely to have in re-

War Has Devastati ng Consequences for Syri as Chi l dren Pages 3-4

Open Ended Worki ng Group on Nucl ear Di sarmament Back Page

DISARMAMENT TIMES is available online at http://www.ngocdps.org.

O

n 2 April 2013, a campaign that spanned two decades and a U.N. process that be-

gan seven years ago came to fruiton when the Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) was ad-

opted by states in the U.N. General Assembly, with 155 votes in favor, 22 abstentons,

and three votes against (Iran, North Korea and Syria). Two months later, on 3 June, the

ATT opened for signature, representng a remarkable victory for a broad coaliton of

progressive states, civil society advocates and responsible industry members, as well

as for the presidents of the July 2012 and March 2013 Diplomatc Conferences at which

the Treaty had been negotated, Ambassador Roberto Garca Moritn of Argentna and

Ambassador Peter Woolcot of Australia, respectvely.

The adopton of the ATT is a signifcant accomplishment. As the frst-ever global

treaty to establish common standards for regulatng the internatonal trade in conven-

tonal arms, the ATT can be a force for good in internatonal relatons. Moreover, if fully

implemented in leter and spirit, it has the potental to fulfl the aims of its proponents

to save lives and protect livelihoods.

The Treaty Text

The ATT obliges states to establish or maintain natonal systems for internatonal arms

transfer control that include but are not limited to:

A control list of conventonal arms, as comprehensive as possible;

o The Treaty covers batle tanks, armoured combat vehicles, large calibre artllery

systems, combat aircraf, atack helicopters, warships, missiles and missile launchers,

and small arms and light weapons. (States are encouraged to control an even broader

list of conventonal arms, however.)

A set of circumstances under which arms should never be transferred;

o These include when arms transfers violate U.N. Security Council measures (such

as embargoes), violate internatonal agreements, or if a state has knowledge the arms

would be used in the commission of genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes or

atacks against civilians.

A natonal risk assessment process;

o An appropriate authority will evaluate the risks that an arms export would contrib-

ute to or facilitate violatons of internatonal human rights or humanitarian law, terror-

ism ofenses, internatonal organized crime, and serious acts of gender-based violence

or violence against women and children.

Measures to prevent diversion of arms transfers, including an assessment of the risk

that an export would be diverted;

Measures to control import, transit, trans-shipment and brokering of conventonal

arms;

A system for keeping records of internatonal arms exports and imports and for re-

portng to the Secretariat on these actvites and on steps taken to implement

the Treaty.

2 Di sar mament Ti mes Summer 2013

laton to human rights law, internatonal

humanitarian law and terrorism, there is

now also a requirement to assess whether

weapons are likely to be used as part of

organized crime. Crucially, there is now

also an explicit provision requiring states

to consider the risk that exported weap-

ons may be used to facilitate gender-based

violence and violence against children. If

states determine there is an overriding

risk of any of these negatve consequenc-

es, they should not authorize the transfer

of weapons.

Despite considerable dislike for the

term overriding risk it remains the

threshold for decisions on whether to

approve or deny weapons exports. Op-

positon to this concept arose principally

amongst the major European Union arms

exportng states who were concerned that

inclusion of the term overriding could al-

low states to proceed with a transfer even

if the transfer poses signifcant risk to in-

ternatonal humanitarian or human rights

law, if the transferring state considers

other overriding circumstances (such as

maintaining peace and security) to exist.

However it became clear during the March

2013 negotatons that acceptng this con-

structon was to be a conditon of U.S.

support for the Treaty. Some states with

well-developed export control systems

have since said they intend to address this

possible ambiguity by interpretng this to

mean that arms exports should be refused

if there is a substantal or clear risk of their

facilitatng violatons of internatonal hu-

man rights law and internatonal humani-

tarian law, terrorism or organized crime,

which they see as a stricter standard.

A similar situaton pertains to states

interpretaton of the scope of the treaty;

although only the seven U.N. categories

of major conventonal weapons and small

arms and light weapons are listed, states

are encouraged to apply the Treatys pro-

visions to the broadest range of conven-

tonal arms (Artcle 5.3). Accordingly, it is

to be expected that early ratfying states

and in partcular signifcant arms export-

ers will make clear that they intend to

interpret the Treatys provisions broadly,

thereby setng a high standard for imple-

mentaton of the Treatys key operatve

provisions and encouraging other states to

do likewise.

The Treatys treatment of ammuni-

ton and parts and components, while an

improvement over earlier drafs, is stll

disappointng in several respects. Primary

among them is the fact that Treaty provi-

sions relatng to import, transit/tranship-

ment, brokering and diversion do not

apply to ammuniton and parts and com-

ponents. The Treaty improves upon the

July 2012 text, however, where ammuni-

ton and parts and components were ad-

dressed in only two sub-paragraphs of an

artcle addressing export issues. As it now

stands, the ATT sets out ammuniton and

parts and components in separate art-

cles which are then referenced at points

throughout the treaty. In one of the most

important substantve developments, am-

muniton and parts and components are

now subject to the same export risk assess-

ment (Artcle 7, as described above) as the

conventonal weapons themselves. This

was not the case in the July 2012 text.

Si gnature, Rati f i cati on

and Entry i nto Force

The Treaty ofcially opened for signature

on 3 June, during a full-day ceremony at

the U.N., which was atended by several

high-level dignitaries, including the U.N.

Secretary General Ban Ki-moon. Among

the statements delivered on that day, sev-

eral governments indicated that their own

interpretaton and applicaton of the Trea-

tys provisions will go beyond what is ex-

plicitly writen in the Treaty. For example:

Ireland said it regarded the scope of

the treaty as wide; Norway said the

treaty will apply to all conventonal weap-

ons; while Uruguay said it too wanted a

broader scope.

Switzerland said it believed that the

scope under Artcle 2 of the Treaty im-

plicitly included gifs, loans and leases.

(Artcle 2 defnes the internatonal trade in

conventonal weapons to include export,

import, transit, trans-shipment, and brok-

ering, which are collectvely referred to as

transfer.)

New Zealand advised delegates that it

would interpret the concept of overriding

risk as a substantal risk.

Looking ahead, Mexico said the Trea-

ty should adapt to future situatons and

Brazil said there is room to strengthen

the Treaty in the future. Norway and New

Zealand agreed that the Treaty could be

improved and strengthened. Switzer-

land said it had always had high expec-

tatons of the Treaty and said that the

process is not fnished, rather, the Treaty

has simply entered a new phase to truly

achieve its purposes.

At tme of writng, more than 70 gov-

ernments have signed the ATT while many

others including the United States have

signalled their intenton to do so in the

very near future. The short tme frame be-

tween the Treatys adopton and the open-

ing for signature posed an administratve

hurdle that prevented some governments

from being able to sign on 3 June. Oth-

ers preferred to wait untl the U.N. General

Assembly High Level Opening in Septem-

ber so that heads of state could sign. It is

widely expected that by the end of 2013,

more than half of all U.N. Member States

will have signed.

Fify state signatories must ratfy the

Treaty to trigger its entry into force, which

could happen as early as 2014. Over the

coming period, the global civil society

movement coordinated by Control Arms,

a global network of non-governmental or-

ganizatons operatng in more than 100

countries will mobilize to encourage and

assist signatory states to ratfy the Treaty

as swifly as possible. This efort will in-

clude engaging with parliamentarians, as

well as providing legal, policy and techni-

cal support and analysis.

Chal l enges of I mpl ementati on

Of course the ATT will have litle impact

if it is not fully implemented by all states

partes. It is clear, even at this early stage,

that some state signatories will require as-

sistance before ratfying the Treaty so that

upon ratfcaton they can fully implement

it. Multlateral insttutons, regional organ-

izatons and civil society will need to work

together to address states specifc needs

and provide assistance. Coordinaton of ef-

fort will be vital, not least in the near-term,

before entry into force and the establish-

ment of the Secretariat to assist partes in

implementng the Treaty.

It is also important to recognize that

prior to the Treatys entry into force there

can be no Conference of States Partes

(which will be responsible for reviewing

implementaton of the Treaty, consider-

ing amendments, and other functons re-

lated to the operaton of the Treaty). This

means there will be no locus or forum for

early ratfying states to discuss issues and

questons relatng to interpretaton and

implementaton of the Treatys provisions.

Opportunites will therefore need to be

created for government experts to meet

informally to discuss implementaton is-

sues from the mechanics of reportng, to

the interpretaton of specifc Treaty provi-

sions and to begin to develop and share

good practces.

Concl usi on

The architects and supporters of a robust

ATT pursued their goal with the intenton

of creatng a dynamic and efectve Treaty

regime that will respond to trends and de-

velopments in the internatonal trade in

arms and address threats to internatonal

and human security. Achieving this out-

come will require all stakeholders includ-

ing progressive states, internatonal civil

society, and responsible defense industry

members to contnue to work together

so that the ATT becomes a reality on the

ground, where it maters.

Enhanced transparency and account-

ability in the internatonal trade in arms

will also be a litmus test for the ATT. In this

regard, there is a partcular and important

role for civil society in scrutnizing govern-

ment acton and holding governments ac-

countable for their Treaty obligatons. The

establishment of a civil society-led moni-

toring regime is being considered, with

the successful Landmine Monitor seen as

a useful model.

Elizabeth Kirkham is small arms and transfer

controls advisor for Saferworld, an independent

internatonal organizaton working to prevent violent

confict and build safer lives. www.saferworld.org.uk

Allison Pytlak is the campaign manager of the

Control Arms coaliton, a global civil society

network operatng in more than 100 countries and

headquartered in New York. More informaton

online at www.controlarms.org and htps://www.

facebook.com/ControlArms

The full text of the Arms Trade Treaty, as well as

informaton about implementaton and ratfcatons

is available at htp://www.un.org/disarmament/ATT/

A r ms T r a d e T r e a t y

Continued from page 1.

With the [Arms Trade

Treaty] the world has

decided to fnally put

an end to the free-

for-all nature of

internatonal weapons

transfers. . . .

The Treaty will provide

an efectve deterrent

against excessive and

destabilizing arms

fows, partcularly

in confict-prone

regions. It will make

it harder for weapons

to be diverted into

the illicit market,

to reach warlords,

pirates, terrorists

and criminals, or to

be used to commit

grave human rights

abuses or violatons

of internatonal

humanitarian law.

Ban Ki - moon, U. N. Secretar y General

Summer 2013 Di sar mament Ti mes 3

The atrocites taking place in Syrias con-

fict now in its third year are well pub-

licized. With increasing frequency, vid-

eos emerge of purported executons and

horrifc violence taking place inside the

country. The fghtng drags on, with more

than 93,000 dead, and the now-numerous

groups in this confict seemingly unwilling

to compromise or give any concessions as

the cycle of vengeance grows.

In early June, U.N. investgators issued

a report concluding that war crimes were

being commited in Syria on a regular ba-

sis, including bombing of civilians and the

recruitment of child fghters, as well as

forcing children to see or partcipate in ma-

cabre killings. The report also concluded

that there were reasonable grounds to

believe that chemical weapons have been

used, although the commission could not

establish which side in the confict may

have used the weapons. The chairman of

the commitee, Paulo Pinheiro, concluded:

Crimes that shock the conscience have

become a daily reality.

The victms in this crisis are many

tmes children; no Syrian, no mater how

young, is spared. Since the confict began,

children have been killed, traumatzed

and deprived of basic needs. The confict

touches them in some cases even before

birth as expectant mothers fee violence.

A recent study conducted by

Baheehir University in Turkey found that

three in four Syrian children have lost a

loved one. More than three million Syrian

children are in need of humanitarian assis-

tance. The harm ranges from being out of

school not getng the educaton that is

a cornerstone for later success to being

recruited into armed groups or targeted

by violence directly. The health care infra-

structure has been hard hit; the number

of hospitals that can functon contnues to

drop, and many mothers can no longer de-

liver their babies safely. Children are going

without needed vaccines, and economic

hardship, as well as the hazardous condi-

tons, make accessing proper nutriton a

daily struggle for many Syrian families.

There are now 1.6 million Syrian

refugees, according to the U.N. Refugee

Agency (UNHCR), with more streaming

into neighboring countries every day. Jor-

dan is home to almost 550,000 refugees,

both in the massive Zaatari camp and in

neighboring communites. Lebanon is over

the 500,000 mark as well, as refugees live

in crowded encampments or seek shelter

in communites throughout the country.

In Iraq, 151,000 refugees have gathered,

mostly in the north, and UNHCR estmates

that fgure could reach 350,000 by the end

of this year.

There are signs that the exodus from

Syria is acceleratng of the 1.6 million ref-

ugees in neighboring countries, one million

have fed this year alone. The fact that this

already unmanageable crisis is worsening

gives us a foreboding picture of what is to

come as the populaton of Syria is forced

to seek refuge in already taxed and over-

crowded neighboring states, which them-

selves are feeling profoundly destabilizing

efects from both the economic demands

of housing so many refugees and the bat-

tle between Syrian President Bashar al-

Assads government and its enemies in the

country and the region.

But the statstcs staggering as they

are dont tell the full story. During a re-

cent visit to Jordan, I spoke with a mother

who traveled, seven months pregnant,

across southern Syria. The risk of giving

birth inside Syria was greater than that

journey. Meanwhile in Lebanon, a col-

league of mine talked with families who

had taken shelter in an abandoned prison,

where a father told her he had been a

banker in Damascus before feeing Syria. A

toddler girl living in the same prison cried

ofen, stll in pain from a piece of shrapnel

that was embedded in her leg.

Just weeks ago I traveled to Iraq,

where I visited the Domiz refugee camp

in the northwestern corner of the country

near its Syrian border. The Kurdistan Re-

gional Government and internatonal non-

governmental organizatons are managing

the camp, trying to provide shelter and

meet the basic needs of 40,000 people in

a space built for 10,000. Some families live

in fimsy plastc tarps, and open sewage

and trash add to their misery. Families told

us of the need to escape as fghtng wors-

ened and their ability to earn a livelihood

for their children vanished of leaving Syr-

ia with only the belongings they could ft in

their car or even carry on foot. Some had

spent almost a year living in this camp, the

hardships of daily life there preferred over

the unbearable realites in Syria.

The day-to-day miseries facing many

families who are refugees or internally

displaced in Syria pose dire health risks

lack of toilets and sewage systems in-

creases the risk of diarrhea, which is the

biggest killer of children globally. Vaccina-

tons have been disrupted. Diseases like

measles have increased. The World Health

Organizaton recently warned that the

risk of epidemic from cholera, typhoid,

hepatts and other ailments has risen

substantally.

Children are also struggling to cope

emotonally with their experiences, which

have lef many in a state of fear and uncer-

tainty. In drawings, refugee children ofen

fll pages with images of weapons, explo-

sions, blood and innocent people being

harmed. The psychological and social im-

pacts on this generaton of Syrian children

are profound.

As long as the war contnues, the un-

imaginable sufering of Syrians will as well.

The confict is so intense that aid cannot

reach those whose need is greatest. With-

out peace, the already-dire humanitarian

crisis will only worsen.

The message must be heard that de-

nying children the right to humanitarian

assistance is a violaton of internatonal hu-

manitarian law. All sides must respect the

fundamental rights of children, which have

been egregiously violated. There is a great

need for increased humanitarian access.

The killing of those providing humanitar-

ian assistance, cumbersome checkpoints,

and fuid boundaries of batle all hamper

the ability of internatonal and civil society

organizaton to deliver aid. The level of ac-

cess pales in proporton to the enormous

and growing needs of Syrians inside the

country.

As the confict drags on, one step that

can be taken immediately is for donor na-

tons to pledge and fulfll all pledges for

aid to fow quickly and efciently to these

refugees. In January of this year, donors

in Kuwait pledged $1.5 billion dollars. The

entrety of this amount must be delivered.

On June 7, the United Natons called for

$5 billion in further spending the largest

appeal of its kind to date a fgure that

refects the magnitude of the crisis as it is

now and as is projected to grow.

But funding alone is not enough. Par-

tes to the confict must respect interna-

tonal laws that govern confict, as well as

Sebastan Meyer/Gety Images for Save the Children

Domiz camp in Iraq, which was originally built for 10,000, has swelled to 40,000 Syrian refugees.

War Has Devastating

Consequences for Syrias Children

Continued on back page.

4 Di sar mament Ti mes Summer 2013

Subscribe to the print edition of Disarmament Times

Sel ect opti on:

Student/Fi xed I ncome $35

I ndi vi dual $45

I ndi vi dual /wi th assoc. membershi p to NGO Commi ttee* $50

Li brary $50

NGOs accredi ted to the Uni ted Nati ons are i nvi ted

to become f ul l members of the NGO Commi ttee. *

Mi ni mum contri buti on $100 / suggested contri buti on $250.

* Appl i cants for associ ate and f ul l membershi p must f i l l out an appl i cati on form,

avai l abl e on our websi te, http: //www. ngocdps. org.

Donate to Di sarmament Ti mes $

Make your check or money order payabl e to NGO Commi ttee on Di sarmament.

Payment must be made through U. S. bank or by i nternati onal money order.

Name

Address

Emai l

Mai l to Di sarmament Ti mes, 777 UN Pl aza, 3B, New York NY 10017.

Renew, donate or si gn up for our emai l edi ti on onl i ne at http: //www. ngocdps. org.

the Conventon on the Rights of the Child, which Syria has ratfed. All actors must cease

to use explosive weapons in areas that are populated with civilians. Children under the

age of 18 must not be recruited into armed groups, and those who have been conscript-

ed must be released.

The confict in Syria is not one the internatonal community can aford to ignore.

The humanitarian crisis will grow likely not in the slow and painfully steady way we

have seen for the past few years, but rapidly and dramatcally. The efect this has on an

entre generaton of Syrias children is immeasurable. They are direct targets of violence,

witnesses to violence, and deprived of health care, educaton and loved ones as a result

of violence. No mater how they are afected, their young lives are being upended by a

bloody war that shows no signs of abatng. We must do everything we can, and urgently,

to mitgate the efects of this confict on them and provide for their basic needs.

And, most important, we must fnd a path to peace in a country that once boasted

high rates of school enrollment among children. Syrias children have already endured

more than any child should be asked to. There is no tme to lose.

Carolyn Miles is president and CEO of Save the Children (savethechildren.org), which serves chil-

dren and families in more than 120 countries globally. Read her blog at htp://loggingcarolynmiles.

savethechildren.org/ or follow her on Twiter at @carolynsave

In March, Save the Children released the report Childhood Under Fire, about the confict in

Syria. You can read it at htp://www.savethechildren.org/at/cf/%7B9def2ebe-10ae-432c-9bd0-

df91d2eba74a%7D/SYRIA-CHILDHOOD-UNDER-FIRE-REPORT-2013.PDF

Editors Note about aid in the region

Save the Children is working in Jordan, Lebanon, and Iraq and inside Syria to reach children.

The organizaton provides educatonal support, creates child-friendly spaces where kids can ex-

press themselves and play in a safe environment, provides vouchers for families to purchase what

they need, distributes hygiene kits and works to ensure that children are protected. As an NGO

focused on the needs of children, Save the Children distributes its aid in an impartal manner,

strictly based on need.

A number of other internatonal and natonal civil society organizatons are also providing aid

in the region.

The U.N. is working to assist children in the region through its various agencies, including

UNICEF, which is providing assistance for child health, nutriton, immunizaton, water and sanita-

ton, as well as educaton and child protecton, and UNHCR, which is providing assistance and

coordinatng response to the refugee crisis. The World Food Program is scaling up plans to provide

food assistance to three million afected people by July and four million by October.

The Cr i s i s i n Sy r i a

Continued from page 3.

Disarmament Times Melissa J. Gillis, editor

Published by NGO Commitee on Disarmament, Peace & Security

777 United Natons Plaza, 3B, New York NY 10017

A substantve issue commitee of the Conference of NGOs

Telephone 212.687.5340 Fax 212.687.1643 Email ngocdps[at]ngocdps[dot]org

Online htp://www.ngocdps.org

Bruce Knots, President, Unitarian Universalist Associaton United Natons Ofce

Editorial Advisors Marcella Shields, Vernon C. Nichols, Ann Hallan Lakhdhir, Robert F. Smylie, Guy Quinlan,

Elizabeth Begley, Hiro Sakurai

Homer A. Jack founded Disarmament Times in 1978.

A new forum on disarmament has started its work in Geneva, an open-ended working

group (OEWG) charged with taking forward multlateral nuclear disarmament nego-

tatons for the achievement and maintenance of a world without nuclear weapons.

Created through the adopton of U.N. General Assembly Resoluton A/RES/67/56, it is

a signal that many states, internatonal organizatons and members of civil society are

running out of patence with the existng deadlocked machinery.

The working group held its frst session 14-24 May in Geneva, with Ambassador

Manuel B. Dengo of Costa Rica as chair, met again on 27 June to collect proposals drawn

from the earlier meetng, and will reconvene from 19-30 August before reportng back

to the General Assembly in October.

The frst two weeks of the working group included a number of panels on topics

such as evaluatng existng commitments, looking at relevant internatonal law and other

disarmament treates, examining the humanitarian impact approach to nuclear weap-

ons, and discussing the role of parliamentarians. The panels also examined concrete

proposals to move forward, such as a treaty banning nuclear weapons.

Afer each panel, delegatons were encouraged to engage in an informal and open

exchange of views. This has allowed for delegatons to break away from prepared state-

ments and is a much-needed shif, which along with the partcipaton of civil society in

the discussions, could lead to a more dynamic interplay of ideas.

Several members of civil society used the open-ended working group as an oppor-

tunity to discuss a treaty banning nuclear weapons, including the idea that negotatons

of such a treaty could start in the near future, even without the partcipaton of nuclear

weapon possessing states, an idea that generated considerable debate.

These discussions revealed misunderstandings and misgivings on the part of some

governmental delegatons regarding a nuclear weapons treaty. Some delegatons incor-

rectly referred to a treaty banning nuclear weapons as a big bang approach which at-

tempts to address all aspects of nuclear weapons, such as the legality, stockpile destruc-

ton and verifcaton in one document. Some seemed to believe that negotatng such a

treaty would undermine existng nuclear Non-Proliferaton Treaty obligatons. To many

in civil society, this thinking is contradictory. In fact, the absence of a clear prohibiton on

nuclear weapons makes it harder to implement a ratonal step-by-step process for either

disarmament or non-proliferaton.

The biggest queston surrounding the open-ended working group is what can it ac-

tually do? There is clearly a need for a forum where discussions about nuclear disarma-

ment can be held without becoming bogged down, like the Conference on Disarma-

ment, by procedural issues. It is unclear what, if any, part the OEWG can play in that,

partcularly given that the fve nuclear powers of the Security Council did not atend.

While approximately 81 states partcipated in at least one of the meetngs during the

frst session of the OEWG, Pakistan and India were the only nuclear-armed states that

took part.

Clearly those who partcipated in the OEWG are frustrated with the lack of progress

on disarmament, but views are divided on how to address it. Should there be a step-

by-step approach, or, alternatvely, negotaton of a treaty that would outlaw nuclear

weapons? Whatever the outcome of the OEWG, it is obvious that contnuing to wait for

progress in the Conference on Disarmament has grown more and more intolerable for

the majority of states. It is also clear that many states desire greater engagement with

civil society on this topic. Whether the open discussions that marked the frst two weeks

of the OEWG can be translated into movement on acton-oriented proposals remains to

be seen.

It now seems advisable for states to make proposals that focus on what individual

governments, or groups of like-minded states, can do vis--vis nuclear disarmament.

Panels and interactve debates are interestng and have their place, but it is past tme

that discussions lead to something more concrete.

Beatrice Fihn is the program manager for Reaching Critcal Will and on the Internatonal Steering

Group of the Internatonal Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). She is based in

Geneva, Switzerland.

Tak i ng Fo r war d Nuc l e ar

Di s ar mame nt Ne g ot i at i o ns ?

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5833)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (405)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Horn of Africa As A Security ComplexDocument18 pagesThe Horn of Africa As A Security ComplexIbrahim Abdi Geele100% (1)

- Battle Rhythm OPT - G4 Slides (19 AUG 14)Document18 pagesBattle Rhythm OPT - G4 Slides (19 AUG 14)Stephen SmithNo ratings yet

- Jose Ignacio Paua - His ExploitsDocument22 pagesJose Ignacio Paua - His ExploitsAnsam Lee100% (1)

- 1 - Microsoft Office Activities and ProjectsDocument137 pages1 - Microsoft Office Activities and Projectsmjae18No ratings yet

- Pendragon Berber & Saracen Characters in PendragonDocument16 pagesPendragon Berber & Saracen Characters in PendragonLeonardo Correia de OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Regs Gunpowder MagazinesDocument24 pagesRegs Gunpowder MagazinesAuldmonNo ratings yet

- Internation Youth Summit For Nuclear Abolition Creates MomentumDocument2 pagesInternation Youth Summit For Nuclear Abolition Creates MomentumDTEeditorNo ratings yet

- 70 Years of Making Nukes: The Lowdown On U.S. ProductionDocument4 pages70 Years of Making Nukes: The Lowdown On U.S. ProductionDTEeditorNo ratings yet

- The Rise of The Drones by M McGivernDocument3 pagesThe Rise of The Drones by M McGivernDTEeditorNo ratings yet

- NGO Spotlight - Loretto Goes To WashingtonDocument5 pagesNGO Spotlight - Loretto Goes To WashingtonDTEeditorNo ratings yet

- New Verification Report Series From NTIDocument2 pagesNew Verification Report Series From NTIDTEeditorNo ratings yet

- A Message From NGOCDPS President Bruce KnottsDocument1 pageA Message From NGOCDPS President Bruce KnottsDTEeditorNo ratings yet

- 2023 Murillo Sandoval Et Al - The Post-Conflict Expansion of Coca Farming and Illicit Cattle Ranching in ColombiaDocument10 pages2023 Murillo Sandoval Et Al - The Post-Conflict Expansion of Coca Farming and Illicit Cattle Ranching in ColombiaJuan Antonio SamperNo ratings yet

- Helen of TroyDocument6 pagesHelen of TroyFernanda ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Project B06Document6 pagesProject B06Melanie JerónimoNo ratings yet

- Enigma and The U-Boat War: Home MenuDocument3 pagesEnigma and The U-Boat War: Home MenuNewvovNo ratings yet

- Migration and Refugee Crisis Faith On The Move July 10 2016Document37 pagesMigration and Refugee Crisis Faith On The Move July 10 2016api-324470913No ratings yet

- Script For Gerph ReportingDocument5 pagesScript For Gerph ReportingDelmar Laurence BergadoNo ratings yet

- Fulltext PDFDocument318 pagesFulltext PDFOmar Al-Ta'eeNo ratings yet

- Breaking The Tether of Fuel 2007Document5 pagesBreaking The Tether of Fuel 2007j_s_fuchsNo ratings yet

- Military - British Army - Hats & CapsDocument61 pagesMilitary - British Army - Hats & CapsThe 18th Century Material Culture Resource Center100% (4)

- 2021 Buyer'S Guide: GlockDocument20 pages2021 Buyer'S Guide: GlockChris HaerringerNo ratings yet

- Modern World HistoryDocument6 pagesModern World Historyapi-276267345No ratings yet

- Risk Battlefield Rogue RulesDocument8 pagesRisk Battlefield Rogue RulesMichael HuynhNo ratings yet

- Quatre Bras 1815Document5 pagesQuatre Bras 1815Peter MunnNo ratings yet

- 0803232446Document641 pages0803232446Bojan KanjaNo ratings yet

- Manipulation of The MediaDocument8 pagesManipulation of The MediaAbigail AnguianoNo ratings yet

- The Unnatural History of Tolkien's OrcsDocument12 pagesThe Unnatural History of Tolkien's OrcsanctrooperNo ratings yet

- Youth Organizations in Great BritainDocument7 pagesYouth Organizations in Great BritainLara FalkonNo ratings yet

- Aikido WordsDocument19 pagesAikido Wordsamaria1No ratings yet

- Cyber TerrorismDocument22 pagesCyber TerrorismgauthamsagarNo ratings yet

- Republic of Korea - Position PaperDocument2 pagesRepublic of Korea - Position PaperihabNo ratings yet

- The Effects of A Nuclear Bomb PDFDocument2 pagesThe Effects of A Nuclear Bomb PDFThe Dangerous OneNo ratings yet

- Norway and The Northern Front: Wartime ProspectsDocument46 pagesNorway and The Northern Front: Wartime ProspectsAlaric SerraNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument353 pagesPDFachysfNo ratings yet

- Declaration of Independence PDFDocument2 pagesDeclaration of Independence PDFEmma Maria Fernando0% (1)