Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reagan Doctrine

Reagan Doctrine

Uploaded by

4dev22Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Reagan Doctrine

Reagan Doctrine

Uploaded by

4dev22Copyright:

Available Formats

Reagan Doctrine

1

Reagan Doctrine

U.S. President Ronald Reagan

The Reagan Doctrine was a strategy orchestrated and

implemented by the United States under the Reagan

Administration to oppose the global influence of the Soviet Union

during the final years of the Cold War. While the doctrine lasted

less than a decade, it was the centerpiece of United States foreign

policy from the early 1980s until the end of the Cold War in 1991.

Under the Reagan Doctrine, the United States provided overt and

covert aid to anti-communist guerrillas and resistance movements

in an effort to "roll back" Soviet-backed communist governments

in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The doctrine was designed to

diminish Soviet influence in these regions as part of the

administration's overall Cold War strategy.

Background

The Reagan Doctrine followed in the tradition of U.S. presidents

developing foreign policy "doctrines", which were designed to

reflect the challenges facing international relations of the times, and propose foreign policy solutions to them. The

practice began with the Monroe Doctrine of President James Monroe in 1823, and continued with the Roosevelt

Corollary, sometimes called the Roosevelt Doctrine, introduced by Theodore Roosevelt in 1904.

The current postWorld War II tradition of Presidential doctrines started with the 1947 Truman Doctrine, under

which the United States provided support to the governments of Greece and Turkey as part of a Cold War strategy to

keep those two nations out of the Soviet sphere of influence. The Truman Doctrine was followed by the Eisenhower

Doctrine, the Kennedy Doctrine, the Johnson Doctrine, the Nixon Doctrine, and the Carter Doctrine, all of which

defined the foreign policy approaches of these respective U.S. presidents on some of the largest global challenges of

their administrations.

Origins of the Reagan Doctrine

Carter administration and Afghanistan

Main article: Operation Cyclone

"To watch the courageous Afghan freedom fighters battle modern arsenals with simple hand-held weapons is an inspiration to those

who love freedom."

U.S. President Ronald Reagan, March 21, 1983

[1]

Reagan Doctrine

2

President Reagan meeting with Afghan

Mujahideen leaders in the Oval Office in 1983

At least one component of the Reagan Doctrine technically pre-dated

the Reagan Presidency. In Afghanistan, the Carter administration

began providing limited covert military assistance to Afghanistan's

mujahideen in an effort to drive the Soviets out of the nation, or at least

raise the military and political cost of the Soviet occupation of

Afghanistan. The policy of aiding the mujahideen in their war against

the Soviet occupation was originally proposed by Carter's national

security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski and was implemented by U.S.

intelligence services. It enjoyed broad bipartisan political support.

Democratic congressman Charlie Wilson became obsessed with the

Afghan cause, and was able to leverage his position on the House Appropriations committees to encourage other

Democratic congressmen to vote for CIA Afghan war money, with the tacit approval of Speaker of the House Tip

O'Neill (D-MA), even as the Democratic party lambasted Reagan for the CIA's secret war in Central America. It was

a complex web of relationships described in George Crile III's book Charlie Wilson's War.

Wilson teamed with CIA manager Gust Avrakotos and formed a team of a few dozen insiders who greatly enhanced

the support for the Mujahideen, funneling it through Zia ul-Haq's ISI. Avrakotos and Wilson charmed leaders from

various anti-Soviet countries including Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Israel, and China to increase support for the rebels.

Avrakotos hired Michael G. Vickers, a young Paramilitary Officer, to enhance the guerilla's odds by revamping the

tactics, weapons, logistics, and training used by the Mujahideen.

[]

Michael Pillsbury, a Pentagon official, and

Vincent Cannistraro pushed the CIA to supply the Stinger missile to the rebels. President Reagan's Covert Action

program has been given credit for assisting in ending the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan.

[2][3]

Heritage Foundation initiatives

With the arrival of the Reagan administration, the Heritage Foundation and other conservative foreign policy think

tanks saw a political opportunity to significantly expand Carter's Afghanistan policy into a more global "doctrine",

including U.S. support to anti-communist resistance movements in Soviet-allied nations in Africa, Asia, and Latin

America. According to the book Rollback, "it was the Heritage Foundation that translated theory into concrete

policy. Heritage targeted nine nations for rollback: Afghanistan, Angola, Cambodia, Ethiopia, Iran, Laos, Libya,

Nicaragua, and Vietnam".

Throughout the 1980s, the Heritage Foundation's foreign policy expert on the Third World, Michael Johns, the

foundation's principal Reagan Doctrine advocate, visited with resistance movements in Angola, Cambodia,

Nicaragua, and other Soviet-supported nations and urged the Reagan administration to initiate or expand military and

political support to them. Heritage Foundation foreign policy experts also endorsed the Reagan Doctrine in two of

their Mandate for Leadership books, which provided comprehensive policy advice to Reagan administration

officials.

[4]

The result was that, in addition to Afghanistan, the Reagan Doctrine was rather quickly applied in Angola and

Nicaragua, with the United States providing military support to the UNITA movement in Angola and the "contras" in

Nicaragua, but without a declaration of war against either country. Addressing the Heritage Foundation in October

1989, UNITA leader Jonas Savimbi called the Heritage Foundation's efforts "a source of great support. No Angolan

will forget your efforts. You have come to Jamba, and you have taken our message to Congress and the

Administration".

[5]

U.S. aid to UNITA began to flow overtly after Congress repealed the Clark Amendment, a

long-standing legislative prohibition on military aid to UNITA.

Following these victories, Johns and the Heritage Foundation urged further expanding the Reagan Doctrine to

Ethiopia, where they argued that the Ethiopian famine was a product of the military and agricultural policies of

Ethiopia's Soviet-supported Mengistu Haile Mariam government. Johns and Heritage also argued that Mengistu's

Reagan Doctrine

3

decision to permit a Soviet naval and air presence on the Red Sea ports of Eritrea represented a strategic challenge to

U.S. security interests in the Middle East and North Africa.

[6]

The Heritage Foundation and the Reagan administration also sought to apply the Reagan Doctrine in Cambodia. The

largest resistance movement fighting Cambodia's communist government was largely made up of members of the

former Khmer Rouge regime, whose human rights record was among the worst of the 20th century. Therefore,

Reagan authorized the provision of aid to a smaller Cambodian resistance movement, a coalition called the Khmer

People's National Liberation Front,

[7]

known as the KPNLF and then run by Son Sann; in an effort to force an end to

the Vietnamese occupation. Eventually, the Vietnamese withdrew, and Cambodia's communist regime fell.

[8]

Then,

under United Nations supervision, free elections were held.

While the Reagan Doctrine enjoyed strong support from the Heritage Foundation and the American Enterprise

Institute, the libertarian-oriented Cato Institute opposed the Reagan Doctrine, arguing in 1986 that "most Third

World struggles take place in arenas and involve issues far removed from legitimate American security needs. U.S.

involvement in such conflicts expands the republic's already overextended commitments without achieving any

significant prospective gains. Instead of draining Soviet military and financial resources, we end up dissipating our

own." Wikipedia:Citation needed

Even Cato, however, conceded that the Reagan Doctrine had "fired the enthusiasm of the conservative movement in

the United States as no foreign policy issue has done in decades". While opposing the Reagan Doctrine as an official

governmental policy, Cato instead urged Congress to remove the legal barriers prohibiting private organizations and

citizens from supporting these resistance movements.

[9]

Reagan administration advocates

The U.S.-supported Nicaraguan contras.

Within the Reagan administration, the doctrine was quickly

embraced by nearly all of Reagan's top national security and

foreign policy officials, including Defense Secretary Caspar

Weinberger, UN Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick, and a series

of Reagan National Security advisers including John

Poindexter, Frank Carlucci, and Colin Powell.

Reagan himself was a vocal proponent of the policy. Seeking

to expand Congressional support for the doctrine in the 1985

State of the Union Address in February 1985, Reagan said:

"We must not break faith with those who are risking their

lives...on every continent, from Afghanistan to Nicaragua...to

defy Soviet aggression and secure rights which have been ours

from birth. Support for freedom fighters is self-defense".

As part of his effort to gain Congressional support for the

Nicaraguan contras, Reagan labeled the contras "the moral equivalent of our founding fathers", which was

controversial because the contras had shown a disregard for human rights.

[10]

There also were allegations that some

members of the contra leadership were involved in cocaine trafficking.

[11]

Reagan and other conservative advocates of the Reagan Doctrine advocates also argued that the doctrine served U.S.

foreign policy and strategic objectives and was a moral imperative against the former Soviet Union, which Reagan,

his advisers, and supporters labeled an "evil empire".

Reagan Doctrine

4

Other advocates

Other early conservative advocates for the Reagan Doctrine included influential conservative activist Grover

Norquist, who ultimately became a registered UNITA lobbyist and an economic adviser to Savimbi's UNITA

movement in Angola,

[12]

and former Reagan speechwriter and current U.S. Congressman Dana Rohrabacher, who

made several secret visits with the mujahideen in Afghanistan and returned with glowing reports of their bravery

against the Soviet occupation.

[13]

Rohrabacher was led to Afghanistan by his contact with the mujahideen, Jack

Wheeler.Wikipedia:Citation needed

Phrase's origin

In 1985, as U.S. support was flowing to the Mujahideen, Savimbi's UNITA, and the Nicaraguan contras, columnist

Charles Krauthammer, in an essay for Time magazine, labeled the policy the "Reagan Doctrine," and the name

stuck.

[14]

"Rollback" replaces "containment"

U.S.-supported UNITA leader Jonas Savimbi.

The Reagan Doctrine was especially significant because it

represented a substantial shift in the postWorld War II foreign

policy of the United States. Prior to the Reagan Doctrine, U.S.

foreign policy in the Cold War was rooted in "containment", as

originally defined by George F. Kennan, John Foster Dulles, and

other postWorld War II U.S. foreign policy experts. In January

1977, four years prior to becoming president, Reagan bluntly

stated, in a conversation with Richard V. Allen, his basic

expectation in relation to the Cold War. "My idea of American

policy toward the Soviet Union is simple, and some would say

simplistic," he said. "It is this: We win and they lose. What do you

think of that?"

[15]

Although a similar policy of "rollback" had been considered on a

few occasions during the Cold War, the U.S. government, fearing

an escalation of the Cold War and possible nuclear conflict, chose

not to confront the Soviet Union directly. With the Reagan

Doctrine, those fears were set aside and the United States began to

openly confront Soviet-supported governments through support of rebel movements in the doctrine's targeted

countries.

One perceived benefit of the Reagan Doctrine was the relatively low cost of supporting guerrilla forces compared to

the Soviet Union's expenses in propping up client states. Another benefit was the lack of direct involvement of

American troops, which allowed the United States to confront Soviet allies without sustaining casualties. Especially

since the September 11 attacks, some Reagan Doctrine critics have argued that, by facilitating the transfer of large

amounts of weapons to various areas of the world and by training military leaders in these regions, the Reagan

Doctrine actually contributed to "blowback" by strengthening some political and military movements that ultimately

developed hostility toward the United States, such as al-Qaeda in Afghanistan.

[16]

However, scholars such as Jason

Burke, Steve Coll, Peter Bergen, Christopher Andrew, and Vasily Mitrokhin have argued that Osama Bin Laden was

"outside of CIA eyesight" and that there is "no support" in any "reliable source" for "the claim that the CIA-funded

bin Laden or any of the other Arab volunteers who came to support the mujahideen".

[17]

However, the American aid

that was given to Pakistans ISI to give to the mujahideen, created long lasting links between mujahideen and

Pakistans secret service. Later, during the Afghan civil war Pakistan sought to promote a faction that would promote

Reagan Doctrine

5

its interests, and potentially help Pakistan in a feared new conflict with India. This led to Pakistani support for the

rise of the Taliban, who were later willing to become allies of Al-Qaeda.

Controversy over Nicaragua

Historian Greg Grandin described a disjuncture between official ideals preached by the United States and actual U.S.

support for terrorism. Nicaragua, where the United States backed not a counter insurgent state but anti-communist

mercenaries, likewise represented a disjuncture between the idealism used to justify U.S. policy and its support for

political terrorism...The corollary to the idealism embraced by the Republicans in the realm of diplomatic public

policy debate was thus political terror. In the dirtiest of Latin Americas dirty wars, their faith in Americas mission

justified atrocities in the name of liberty .

[18]

Grandin examined the behaviour of the U.S.-backed contras and found

evidence that it was particularly inhumane and vicious: "In Nicaragua, the U.S.-backed Contras decapitated,

castrated, and otherwise mutilated civilians and foreign aid workers. Some earned a reputation for using spoons to

gorge their victims eyes out. In one raid, Contras cut the breasts of a civilian defender to pieces and ripped the flesh

off the bones of another.

[19]

Professor Frederick H. Gareau has written that the Contras "attacked bridges, electric generators, but also

state-owned agricultural cooperatives, rural health clinics, villages, and non-combatants". U.S. agents were directly

involved in the fighting. "CIA commandos launched a series of sabotage raids on Nicaraguan port facilities. They

mined the country's major ports and set fire to its largest oil storage facilities." In 1984 the U.S. Congress ordered

this intervention to be stopped; however, it was later shown that the Reagan administration illegally continued (See

Iran-Contra affair). Gareau has characterized these acts as "wholesale terrorism" by the United States.

A CIA manual for training the Nicaraguan Contras in psychological operations, leaked to the media in 1984, entitled

"Psychological Operations in Guerrilla War". recommended selective use of violence for propagandistic effects

and to neutralize government officials. Nicaraguan Contras were taught to lead:

...selective use of armed force for PSYOP psychological operations effect.... Carefully selected, planned

targets judges, police officials, tax collectors, etc. may be removed for PSYOP effect in a UWOA

unconventional warfare operations area, but extensive precautions must insure that the people concur in such

an act by thorough explanatory canvassing among the affected populace before and after conduct of the

mission.

James Bovard,Freedom Daily

Similarly, former diplomat Clara Nieto, in her book Masters of War, charged that "the CIA launched a series of

terrorist actions from the mothership off Nicaraguas coast. In September 1983, she charged the agency attacked

Puerto Sandino with rockets. The following month, frogmen blew up the underwater oil pipeline in the same

portthe only one in the country. In October there was an attack on Puerto Corinto, Nicaraguas largest port, with

mortars, rockets, and grenades blowing up five large oil and gasoline storage tanks. More than a hundred people

were wounded, and the fierce fire, which could not be brought under control for two days, forced the evacuation of

23,000 people.

The International Court of Justice, when judging the case of Nicaragua v. United States in 1984, found that the

United states was obligated to pay reparations to Nicaragua, because it had violated international law by actively

supporting the Contras in their rebellion and by mining the Naval waters of Nicaragua. The United States refused to

participate in the proceedings after the Court rejected its argument that the ICJ lacked jurisdiction to hear the case.

The U.S. later blocked the enforcement of the judgment by exercising its veto power in the United Nations Security

Council and so prevented Nicaragua from obtaining any actual compensation.

[20]

Supporters of the Reagan administration have pointed out that the United States had been the largest provider of aid

to Nicaragua, and twice offered to resume aid if the Sandinstas agreed to stop arming the communist insurgency

against the military government in El Salvador.

[21]

Former official Roger Miranda wrote that "Washington could not

ignore Sandinista attempts to overthrow Central American governments."

[22]

Nicaraguas Permanent Commission on

Reagan Doctrine

6

Human Rights condemned Sandinista human rights violations, recording at least 2,000 murders in the first six

months and 3,000 disappearances in the first few years. It has since documented 14,000 cases of torture, rape,

kidnapping, mutilation and murder.

[23]

The UN International Commission of Jurists found that the Sandinista

Peoples Courts aimed to suppress all political opposition. The Permanent Commission on Human Rights identified

6,000 political prisoners. The Sandinistas admitted to forcing 180,000 peasants into resettlement camps.

[24]

Leading

Sandinistas saw the revolt as a popular uprising. The Contras became "a campesino movement with its own

leadership" (Luis Carrion); they had "a large social base in the countryside" (Orlando Nunez); "the integration of

thousands of peasants into the counterrevolutionary army" was provoked by "the policies, limitations and errors of

Sandinismo" (Alejandro Bendana); "many landless peasants went to war" to avoid the state collectives, and Contra

commanders "were small farmers, many of them without any ties to Somocismo, who had supplanted the former

[Somoza] National Guard officers" (Sergio Ramirez). Thus, it is not universally accepted that the majority of Contras

resorted to terroristic tactics.

[25]

Jamie Glazov, comparing the Sandinistas to the Khmer Rouge, wrote, "the Sandinistas inflicted a ruthless forcible

relocation of tens of thousands of Indians from their land. Like Stalin, they used state-created famine as a weapon

against these 'enemies of the people.' The Sandinista army committed myriad atrocities against the Indian population,

killing and imprisoning approximately 15,000 innocent people..."

[26]

Covert implementation

As the Reagan administration set about implementing the Heritage Foundation plan in Afghanistan, Angola, and

Nicaragua, it first attempted to do so covertly, not as part of official policy. "The Reagan government's initial

implementation of the Heritage plan was done covertly", according to the book Rollback, "following the

longstanding custom that containment can be overt but rollback should be covert." Ultimately, however, the

administration supported the policy more openly.

Congressional votes

While the doctrine benefited from strong support from the Reagan administration, the Heritage Foundation and

several influential Members of Congress, many votes on critical funding for resistance movements, especially the

Nicaraguan contras, were extremely close, making the Reagan Doctrine one of the more contentious American

political issues of the late 1980s.

[27]

Reagan Doctrine and the Cold War's end

As arms flowed to the contras, Savimbi's UNITA and the mujahideen, the Reagan Doctrine's advocates argued that

the doctrine was yielding constructive results for U.S. interests and global democracy.

In Nicaragua, pressure from the Contras led the Sandinstas to end the State of Emergency, and they subsequently lost

the 1990 elections. In Afghanistan, the mujahideen bled the Soviet Union's military and paved the way for Soviet

military defeat. In Angola, Savimbi's resistance ultimately led to a decision by the Soviet Union and Cuba to bring

their troops and military advisors home from Angola as part of a negotiated settlement. In Cambodia, the Vietnamese

withdrew and their allied government collapsed.

All of these developments were Reagan Doctrine victories, the doctrine's advocates argue, laying the ground for the

ultimate dissolution of the Soviet Union.

[28]

Michael Johns later argued that "the Reagan-led effort to support

freedom fighters resisting Soviet oppression led successfully to the first major military defeat of the Soviet

Union...Sending the Red Army packing from Afghanistan proved one of the single most important contributing

factors in one of history's most profoundly positive and important developments".

[29]

Reagan Doctrine

7

Soviet troops withdrawing from Afghanistan in 1988, following a

nine-year occupation.

However, there is considerable disagreement over the

importance of Reagan's role in the disintegration of the

Soviet Union.

[30]

Thatcher's view

Among others, Margaret Thatcher, Prime Minister of

the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990, has credited

the Reagan Doctrine with aiding the end of the Cold

War. In December 1997, Thatcher said that the Reagan

Doctrine "proclaimed that the truce with communism

was over. The West would henceforth regard no area of

the world as destined to forego its liberty simply

because the Soviets claimed it to be within their sphere

of influence. We would fight a battle of ideas against communism, and we would give material support to those who

fought to recover their nations from tyranny".

[31]

IranContra Affair

U.S. funding for the Contras, who opposed the Sandinista government of Nicaragua, was obtained from covert

sources. The U.S. Congress did not authorize sufficient funds for the Contras' efforts, and the Boland Amendment

barred further funding. In 1986, in an episode that became known as The IranContra affair, the Reagan

administration illegally facilitated the sale of arms to Iran, the subject of an arms embargo, in the hope that the arms

sales would secure the release of hostages and allow U.S. intelligence agencies to fund the Nicaraguan Contras.

Reagan Doctrine

8

Death of Savimbi

In February 2002, UNITA's Jonas Savimbi was killed by Angolan military forces in an ambush in eastern Angola.

Savimbi was succeeded by a series of UNITA leaders, but the movement was so closely associated with Savimbi that

it never recovered the political and military clout it held at the height of its influence in the late 1980s.

End of Reagan Doctrine

Tomb of Afghan mujahideen resistance leader

Ahmad Shah Massoud, in Afghanistan's Panjshir

Valley.

The Reagan Doctrine, while closely associated with the foreign policy

of Ronald Reagan and his administration, continued into the

administration of Reagan's successor, George H. W. Bush, who

assumed the U.S. presidency in January 1989. But Bush's Presidency

featured the final year of the Cold War and the Gulf War, and the

Reagan Doctrine soon faded from U.S. policy as the Cold War began

to end.

[32]

Bush also noted a peace dividend to the end of the Cold War

with economic benefits of a decrease in defense spending. After the

presidency of Bill Clinton, a change in United States foreign policy

was introduced with the presidency of his son George W. Bush and the

new Bush Doctrine, who increased military spending from the former

presidency of Bill Clinton.

In Nicaragua, the Contra War ended after the Sandinista government,

facing military and political pressure, agreed to new elections, in which

the contras' political wing participated, in 1990. In Angola, an

agreement in 1989 met Savimbi's demand for the removal of Soviet,

Cuban and other military troops and advisers from Angola. Also in

1989, in relation to Afghanistan, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev

labeled the war against the U.S.-supported mujahideen a "bleeding

wound" and ended the Soviet occupation of the country.

[33]

References

[1] Message on the Observance of Afghanistan Day (http:/ / www. reagan. utexas. edu/ archives/ speeches/ 1983/ 32183e. htm) by U.S. President

Ronald Reagan, March 21, 1983

[2] http:/ / www. globalissues. org/ article/ 258/ anatomy-of-a-victory-cias-covert-afghan-war

[3] [3] Victory: The Reagan Administration's Secret Strategy That Hastened the Collapse of the Soviet Union (Paperback) by Peter Schweizer,

Atlantic Monthly Press, 1994 page 213

[4] "Think tank fosters bloodshed, terrorism", The Daily Cougar, August 22, 2008. (http:/ / thedailycougar. com/ 2008/ 08/ 22/

think-tank-fosters-bloodshed-terrorism/ )

[5] "The Coming Winds of Democracy in Angola," by Jonas Savimbi, Heritage Foundation Lecture #217, October 5, 1989. (http:/ / www.

heritage.org/ Research/ Africa/ HL217.cfm)

[6] "A U.S. Strategy to Foster Human Rights in Ethiopia, by Michael Johns, Heritage Foundation Backgrounder #692, February 23, 1989. (http:/

/ www.heritage. org/ research/ MiddleEast/ bg692. cfm)

[7] [7] Far Eastern Economic Review, December 22, 1988, details the extensive fighting between the U.S.-backed forces and the Khmer Rouge.

[8] "Cambodia at a Crossroads", by Michael Johns, The World and I magazine, February 1988. (http:/ / www. worldandi. com/ specialreport/

1988/ february/ Sa13957. htm)

[9] "U.S. Aid to Anti-Communist Rebels: The 'Reagan Doctrine' and Its Pitfalls," Cato Institute, June 24, 1986. (http:/ / www. cato. org/ pubs/

pas/ pa074.html)

[10] "In Reagan's Footsteps," Jewish World Review, November 14, 2003. (http:/ / www. jewishworldreview. com/ jeff/ jacoby111403. asp)

[11] "The Contras and Cocaine" (http:/ / prorev.com/ blum. htm), Progressive Review, testimony to U.S. Senate Select Committee on

Intelligence Hearing on the Allegations of CIA Ties to Nicaraguan Contra Rebels and Crack Cocaine in American Cities, October 23, 1996.

[12] "Savimbi's Shell Game," Bnet.com, March 1998 (http:/ / www. findarticles. com/ p/ articles/ mi_hb1367/ is_199803/ ai_n6384825)

Reagan Doctrine

9

[13] "Profile: Dana Rohrabacher," Cooperative History Research Commons, September 17, 2001. (http:/ / www. cooperativeresearch. org/ entity.

jsp?id=1521846767-2190)

[14] "The Reagan Doctrine" (http:/ / www.time.com/ time/ magazine/ article/ 0,9171,964873,00. html), by Charles Krauthammer, Time

magazine, April 1, 1985.

[15] The Man Who Won the Cold War, by [[Richard V. Allen (http:/ / www. hoover. org/ publications/ hoover-digest/ article/ 7398)]]

[16] "Think Tank Fosters Bloodshed, Terrorism," The Cougar, August 25, 2008. (http:/ / media. www. thedailycougar. com/ media/ storage/

paper1206/ news/ 2008/ 08/ 25/ Opinion/ Think.Tank. Fosters. Bloodshed. Terrorism-3401834. shtml)

[17] [17] See Jason Burke, Al-Qaeda (Penguin, 2003), p59; Steve Coll, Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan and Bin Laden

(Penguin, 2004), p87; Peter Bergen, The Osama bin Laden I Know (Free Press, 2006), pp60-1; Christopher Andrew and Vasili Mitrokhin, The

Mitrokhin Archive II: The KGB and the World (Penguin, 2006), p579n48.

[18] Grandin, Greg. Empires Workshop: Latin America, The United States and the Rise of the New Imperialism, Henry Holt & Company 2007,

89

[19] Grandin, Greg. Empires Workshop: Latin America, The United States and the Rise of the New Imperialism, Henry Holt & Company 2007,

90

[20] [20] "Appraisals of the ICJ's Decision. Nicaragua vs United State (Merits)"

[21] Dissenting Opinion of Judge Schwebel, Nicaragua v. United States of America Merits, ICJ, June 27, 1986, Factual Appendix, paras. 15-8,

22-5. See also Sandinista admissions in Miami Herald, July 18, 1999.

[22] [22] Roger Miranda and William Ratliff, The Civil War in Nicaragua (Transaction, 1993), pp116-8.

[23] [23] John Norton Moore, The Secret War in Central America (University Publications of America, 1987) p143n94 (2,000 killings); Roger

Miranda and William Ratliff, The Civil War in Nicaragua (Transaction, 1993), p193 (3,000 disappearances); Insight on the News, July 26,

1999 (14,000 atrocities).

[24] [24] Humberto Belli, Breaking Faith (Puebla Institute, 1985), pp124, 126-8.

[25] Robert S. Leiken, Why Nicaragua Vanished (Rowman & Littlefield, 2003), pp148-9, 159. See also Robert P. Hager, The Origins of the

Contra War in Nicaragua, Terrorism and Political Violence, Spring 1998.

[26] Glazov, Jamie, Remembering Sandinsta Genocide (http:/ / archive. frontpagemag. com/ readArticle. aspx?ARTID=25257), FrontPage

Magazine, June 5, 2002.

[27] A Twilight Struggle: American Power and Nicaragua, 1977-1990, Robert Kagan, Simon & Schuster, 1996.

[28] "It Was Reagan Who Tore Down That Wall," Dinesh D'Souza, Los Angeles Times, November 7, 2004.

[29] "Charlie Wilson's War Was Really America's War," by Michael Johns (http:/ / michaeljohnsonfreedomandprosperity. blogspot. com/ 2008/

01/ charlie-wilsons-war-was-really-americas.html), January 19, 2008.

[30] http:/ / hnn. us/ articles/ 5569. html

[31] "The Principles of Conservatism," by Margaret Thatcher, Lecture to the Heritage Foundation, December 10, 1997. (http:/ / www.

margaretthatcher.org/ speeches/ displaydocument.asp?docid=108376)

[32] Excerpted from The Reagan Doctrine: Third World Rollack, End Press, 1989. (http:/ / www. doublestandards. org/ gould1. html)

[33] "The Soviet Decision to Withdraw, 1986-1988" U.S. Library of Congress (http:/ / countrystudies. us/ afghanistan/ 96. htm).

Further reading

Meiertns, Heiko (2010). The Doctrines of US Security Policy: An Evaluation under International Law.

Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-76648-7.

External links

Description and history

"The Reagan Doctrine: The Guns of July" (http:/ / www. foreignaffairs. org/ 19860301faessay7785/

stephen-s-rosenfeld/ the-reagan-doctrine-the-guns-of-july. html), by Stephen S. Rosenfeld, Foreign Affairs

magazine, Spring 1986.

Reagan Doctrine

10

Academic sources

The Reagan Doctrine: Sources of American Conduct in the Cold War's Last Chapter (http:/ / www. greenwood.

com/ catalog/ C4798. aspx), by Mark P. Lagon, Praeger Publishers, 1994.

The Great Transition: American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War (http:/ / www. questia. com/ PM.

qst?a=o& d=29069917), by Raymond L. Garthoff, Brookings Institution, 1994.

Deciding to Intervene: The Reagan Doctrine and American Foreign Policy (http:/ / www. questia. com/ PM.

qst?a=o& d=98521364), by James M. Scott, Duke University Press, 1996.

"Freedom fighters in Angola: Test Case for the Reagan Doctrine" (http:/ / repository. library. georgetown. edu/

handle/ 10822/ 552556), The Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives, Georgetown University,

November 16, 1985.

"The Lessons of Afghanistan" (http:/ / www. unz. org/ Pub/ PolicyRev-1987q2-00032), by Michael Johns, Policy

Review magazine, Spring 1987.

"A U.S. Strategy to Foster Human Rights in Ethiopia" (http:/ / www. heritage. org/ research/ MiddleEast/ bg692.

cfm), by Michael Johns, Heritage Foundation Backgrounder # 692, February 23, 1989.

"The Coming Winds of Democracy in Angola" (http:/ / www. heritage. org/ Research/ Africa/ HL217. cfm), by

Jonas Savimbi, Heritage Foundation Lecture # 217, October 4, 1989.

"Savimbi's Elusive Victory in Angola" (http:/ / thomas. loc. gov/ cgi-bin/ query/ z?r101:E26OC9-320:), by

Michael Johns, Congressional Record, October 26, 1989.

"The Principles of Conservatism" (http:/ / www. margaretthatcher. org/ speeches/ displaydocument.

asp?docid=108376), by Honorable Margaret Thatcher, Heritage Foundation Lecture, December 10, 1997.

"The Ash Heap of History: President Reagan's Westminster Address 20 Years Later" (http:/ / www.

reagansheritage. org/ html/ reagan_panel_kraut. shtml), by Charles Krauthammer, Heritage Foundation Lecture,

June 3, 2002.

"U.S. Aid to Anti-Communist Rebels: The 'Reagan Doctrine' and its Pitfalls" (http:/ / www. cato. org/ pubs/ pas/

pa074es. html), by Ted Galen Carpenter, Cato Policy Analysis # 74, Cato Institute, June 24, 1986.

"The Contras, Cocaine, and Covert Operations" (http:/ / www2. gwu. edu/ ~nsarchiv/ NSAEBB/ NSAEBB2/

nsaebb2. htm), by Gary Webb, National Security Archive, George Washington University, August 1996.

"How We Ended the Cold War" (http:/ / www. thenation. com/ article/ how-we-ended-cold-war), by John Tirman,

The Nation, October 14, 1999.

"Think Tank Fosters Bloodshed, Terrorism" (http:/ / thedailycougar. com/ 2008/ 08/ 22/

think-tank-fosters-bloodshed-terrorism/ ), The Daily Cougar, August 25, 2008.

Article Sources and Contributors

11

Article Sources and Contributors

Reagan Doctrine Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?oldid=595193660 Contributors: 72Dino, Ace of Raves, Adelson Velsky Landis, AfricaEditor, Afrique, Alan Liefting, Altenmann,

Amyzex, Andonic, Andy Marchbanks, Arj, Artdriver, Atrix20, Bellerophon5685, Bender235, Bkonrad, BlackAndy, Blue387, Bobrayner, Byelf2007, CWenger, Cactus Guru, CartoonDiablo,

Chisme, Chris Chittleborough, Chris.Cole.DC, Ciro612, Ckatz, Cornell92, Cypher z, DTMGO, David H Braun (1964), DavidLevinson, Decora, Descendall, Dino, Doc9871, Doh5678,

Dragonivich65, Drbreznjev, EdibleKarma, Edward, Ejrcito Rojo 1950, Everyking, Groggy Dice, Haeinous, Happyme22, HoyaProff, Ironislucky, J36miles, James084, Jefflayman, Jengod,

Jermtermfirm, John of Reading, JohnOwens, Johnnyboy19376, Joseph Solis in Australia, Josve05a, KI, Kaisershatner, Kalsermar, KansaiKitsune, Katydidit, KenFehling, Kuralyov,

Kwamikagami, Lao Wai, Lapsed Pacifist, Leonard G., Levineps, Liface, Lightmouse, LilHelpa, Lionelt, Loremaster, Lususromulus, MaGioZal, Mathmannix, MaulYoda, Mcgovernpeto, Mild Bill

Hiccup, Mitrius, Mjf08, Mogism, Mukogodo, NYCJosh, Numlockf6, ObjectivityAlways, Ohnoitsjamie, Ot, Ottawakismet, PAWiki, PTJoshua, Petri Krohn, PhnomPencil, PigFlu Oink, Pigman,

Porqin, Quarl, Rcsprinter123, Redthoreau, Rettoper, Reydeyo, Rougher07, Routlee, Ruhrfisch, Russavia, Rzuwig, Sadads, Salamurai, Sardanaphalus, Saxonthedog, ScierGuy, Seergenius,

Skeptiod60, SlimVirgin, Solidusspriggan, Soxwon, Sross (Public Policy), Stevenmitchell, TJive, Tec15, TheJazzDalek, TheTimesAreAChanging, TimElessness, Trachtemacht, Vanamonde93,

Vindalfr, Vints, Viriditas, Vzbs34, William.riker2335, Wolfkeeper, WulfTheSaxon, Yopienso, 200 anonymous edits

Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors

File:Official Portrait of President Reagan 1981.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Official_Portrait_of_President_Reagan_1981.jpg License: Public Domain

Contributors: Admrboltz, Amikeco, Catalaalatac, Color, Ds02006, Happyme22, Harpsichord246, Julia W, Kintetsubuffalo, MartinHagberg, Mogelzahn, R-41, Slarre, Takabeg, Tcho, Tom, 2

anonymous edits

File:Reagan sitting with people from the Afghanistan-Pakistan region in February 1983.jpg Source:

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Reagan_sitting_with_people_from_the_Afghanistan-Pakistan_region_in_February_1983.jpg License: Public Domain Contributors: Unknown,

possibly Tim Clary

File:Frente Sur Contras 1987.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Frente_Sur_Contras_1987.jpg License: Creative Commons Attribution-Sharealike 3.0 Contributors:

Tiomono (talk) Original uploader was Tiomono at en wikipedia

File:Jonas Savimbi.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Jonas_Savimbi.jpg License: GNU Free Documentation License Contributors: Ernmuhl

File:Evstafiev-afghan-apc-passes-russian.jpg Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:Evstafiev-afghan-apc-passes-russian.jpg License: Creative Commons

Attribution-Sharealike 2.5 Contributors: Mikhail Evstafiev

File:The body of Ahmad Shah Massoud.JPG Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=File:The_body_of_Ahmad_Shah_Massoud.JPG License: Public Domain Contributors: U.S.

Army photo by Sgt. Teddy Wade

License

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

//creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5825)

- International Bill of Exchange TemplateDocument1 pageInternational Bill of Exchange Templatejj86% (95)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (903)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Content Analysis of Textbook From Human Rights Perspective - RukhsanaDocument13 pagesContent Analysis of Textbook From Human Rights Perspective - RukhsanaWaseem Khan67% (3)

- The Effect of Profit or Loss On Capital and The Double Entry System For Expenses and RevenuesDocument23 pagesThe Effect of Profit or Loss On Capital and The Double Entry System For Expenses and RevenuesEricKHLeawNo ratings yet

- Documents Search Results (1000) : Export Date: 11/11/2019 TitleDocument3 pagesDocuments Search Results (1000) : Export Date: 11/11/2019 Title4dev22No ratings yet

- Financial PerspectiveDocument54 pagesFinancial Perspective4dev22No ratings yet

- List of Files Created 1 July To 31 December 2017Document3 pagesList of Files Created 1 July To 31 December 20174dev22No ratings yet

- Archiving Process MapDocument1 pageArchiving Process Map4dev22No ratings yet

- At The Core of Performance - Part 2Document70 pagesAt The Core of Performance - Part 24dev22No ratings yet

- The Geopolitics of Sonatrach - A History Interwoven With Algeria'sDocument14 pagesThe Geopolitics of Sonatrach - A History Interwoven With Algeria's4dev22No ratings yet

- The Joint Clinical Trials Office: Clinical Trial Archive DocumentDocument1 pageThe Joint Clinical Trials Office: Clinical Trial Archive Document4dev22No ratings yet

- Why Evidence Matters: From Text To Talk To ArgumentDocument35 pagesWhy Evidence Matters: From Text To Talk To Argument4dev22No ratings yet

- IRMT Electronic RecsDocument195 pagesIRMT Electronic Recs4dev22100% (1)

- SOP Template Archiving of Essential Documents v5.1Document5 pagesSOP Template Archiving of Essential Documents v5.14dev22No ratings yet

- The Modern Civil Rights Movement, Social Critics, and NonconformistsDocument17 pagesThe Modern Civil Rights Movement, Social Critics, and Nonconformists4dev22No ratings yet

- TOR Records Management Consultancy Sept 2014Document4 pagesTOR Records Management Consultancy Sept 20144dev22No ratings yet

- Psychoanalytic Criticism (20111205)Document10 pagesPsychoanalytic Criticism (20111205)4dev22No ratings yet

- The International Research FoundationDocument6 pagesThe International Research Foundation4dev22No ratings yet

- Notepad 2Document10 pagesNotepad 24dev22No ratings yet

- 21ST Century Reaction PaperDocument1 page21ST Century Reaction PaperJehyne CataluñaNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitDocument9 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Tenth CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- DOJ BriefDocument25 pagesDOJ BriefIan MillhiserNo ratings yet

- Spotlight 447 Trends in North Carolina State Spending: Total State Spending Has Grown After Both Inflation and Per Capita AdjustmentsDocument7 pagesSpotlight 447 Trends in North Carolina State Spending: Total State Spending Has Grown After Both Inflation and Per Capita AdjustmentsJohn Locke FoundationNo ratings yet

- NWIM - Participant Guide PDFDocument615 pagesNWIM - Participant Guide PDFJack JackNo ratings yet

- Citizens Defending Libraries Complaint Filed 7-10-13 Against The NYPLDocument31 pagesCitizens Defending Libraries Complaint Filed 7-10-13 Against The NYPLMichael D D WhiteNo ratings yet

- Buebos Vs PeopleDocument14 pagesBuebos Vs PeopleClaudine Christine A. VicenteNo ratings yet

- FIATA Reference Handbook 05-2014Document64 pagesFIATA Reference Handbook 05-2014Fwdr Livingston Obasi0% (1)

- EVYLCDocument2 pagesEVYLCEf LawmeknowkeyNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae - Galih Ramdhan PermanaDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae - Galih Ramdhan PermanaGalih R PermanaNo ratings yet

- Paunon vs. UyDocument11 pagesPaunon vs. UyKen MPNo ratings yet

- Chapter 19Document41 pagesChapter 19Tati AnaNo ratings yet

- Form - I (A) : Department of Commercial Taxes, Government of Uttar PradeshDocument4 pagesForm - I (A) : Department of Commercial Taxes, Government of Uttar PradeshPrakhar JainNo ratings yet

- BGC S4hana2021 BPD en XXDocument12 pagesBGC S4hana2021 BPD en XXvenkatNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 6 Work Energy and PowerDocument34 pagesChapter - 6 Work Energy and PowerNafees FarheenNo ratings yet

- Emergency Notification Server: Installation ManualDocument41 pagesEmergency Notification Server: Installation ManualMarcelo Ratto CampiNo ratings yet

- 019GMA Network Vs Commission On Elections, 734 SCRA 88, G.R. No. 205357, September 2, 2014Document165 pages019GMA Network Vs Commission On Elections, 734 SCRA 88, G.R. No. 205357, September 2, 2014Lu CasNo ratings yet

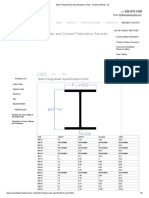

- Wide Flange Beam Specifications Chart - South El Monte, CADocument3 pagesWide Flange Beam Specifications Chart - South El Monte, CAToniNo ratings yet

- People v. Tiu Won ChuaDocument1 pagePeople v. Tiu Won Chuamenforever100% (1)

- Mamada - Culminating Project Final Presentation-AMDocument54 pagesMamada - Culminating Project Final Presentation-AMAmana IftekharNo ratings yet

- Biznet Networks - Service Change Form: Customer InformationDocument2 pagesBiznet Networks - Service Change Form: Customer Informationmh5dnwfxNo ratings yet

- Camp McQuaide HistoryDocument15 pagesCamp McQuaide HistoryCAP History LibraryNo ratings yet

- Invoice FANDocument1 pageInvoice FANVarsha A Kankanala0% (1)

- Chapter 15: Designing and Managing Integrated Marketing ChannelsDocument9 pagesChapter 15: Designing and Managing Integrated Marketing ChannelsNicole OngNo ratings yet

- Blaw SoftDocument596 pagesBlaw Softjonathan tanNo ratings yet

- Notice:::: Downloaded On - 23-01-2023 10:58:50Document319 pagesNotice:::: Downloaded On - 23-01-2023 10:58:50Janak RajNo ratings yet

- Industrial Security ManagementDocument16 pagesIndustrial Security Managementgema alinao100% (1)