Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Commonwealth Fund EHR Survey

Commonwealth Fund EHR Survey

Uploaded by

HLMeditCopyright:

Available Formats

You might also like

- Benefits of Iclinicsys in The Rural Health Unit of Lupi, Camarines SurDocument5 pagesBenefits of Iclinicsys in The Rural Health Unit of Lupi, Camarines Surattyleoimperial100% (1)

- Case Study 1Document3 pagesCase Study 1Dwaine TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument6 pagesReview of Related LiteratureSkyla FiestaNo ratings yet

- Case 1-2 Business Case Data Chaos Creates RiskDocument5 pagesCase 1-2 Business Case Data Chaos Creates RiskfauziahezzyNo ratings yet

- AMA Letter To DOJ Regarding CVS Aetna MergerDocument141 pagesAMA Letter To DOJ Regarding CVS Aetna MergerHLMedit100% (1)

- OSF HealthCare Prevails in Dispute Over Church PlanDocument16 pagesOSF HealthCare Prevails in Dispute Over Church PlanHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Hammer Plea AgreementDocument31 pagesHammer Plea AgreementHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Pfizer Corporate Integrity Agreement (HHS OIG)Document53 pagesPfizer Corporate Integrity Agreement (HHS OIG)HLMeditNo ratings yet

- What Is Computer ApplicationsDocument6 pagesWhat Is Computer ApplicationsElle7loboNo ratings yet

- Article 3Document12 pagesArticle 3مالك مناصرةNo ratings yet

- Hit Research ProjectDocument20 pagesHit Research ProjectDavid JuarezNo ratings yet

- Order ### 2672790Document11 pagesOrder ### 2672790Wallace Mandela Ong'ayoNo ratings yet

- E PrescribingDocument6 pagesE Prescribingapi-326037307No ratings yet

- Term Paper Complete DraftDocument16 pagesTerm Paper Complete Draftapi-464597952No ratings yet

- Role of Healthcare Law in Regards To InformaticsDocument8 pagesRole of Healthcare Law in Regards To InformaticsTimothyCLentzJr.100% (1)

- 73 Integration2010 ProceedingsDocument9 pages73 Integration2010 ProceedingsKhirulnizam Abd RahmanNo ratings yet

- Tizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Document4 pagesTizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Royce Vincent TizonNo ratings yet

- Hospitals and Health Networks Magazine's 2015 Most WiredDocument15 pagesHospitals and Health Networks Magazine's 2015 Most WiredWatertown Daily TimesNo ratings yet

- Business Case: Data Chaos Creates RiskDocument3 pagesBusiness Case: Data Chaos Creates RiskRizka DestianaNo ratings yet

- Issues in International Health Policy: Electronic Health Records: An International Perspective On "Meaningful Use"Document18 pagesIssues in International Health Policy: Electronic Health Records: An International Perspective On "Meaningful Use"Sevi Cephy ONo ratings yet

- HMODocument8 pagesHMOrunass_07No ratings yet

- Tihp It 012610Document7 pagesTihp It 012610api-258667648No ratings yet

- Hcin 540 - Term PaperDocument16 pagesHcin 540 - Term Paperapi-428767663No ratings yet

- 5 Benefits of Technology in HealthcareDocument2 pages5 Benefits of Technology in HealthcareCHUAH TZE YEE MoeNo ratings yet

- Hesr 53 3270Document8 pagesHesr 53 3270Kyle Isidro MaleNo ratings yet

- Nkrouse Revanthgurram Jiqinli Shanniwu Xinyizhang White PaperDocument9 pagesNkrouse Revanthgurram Jiqinli Shanniwu Xinyizhang White Paperapi-247217685No ratings yet

- According To JMIR PublicationsDocument3 pagesAccording To JMIR PublicationsJanine KhoNo ratings yet

- Final Final HSM PaperDocument20 pagesFinal Final HSM PaperJamie JacksonNo ratings yet

- The Role of Information Technology in Pharmacy Practice Is Dynamic and Not Likely To Lose Relevance in The Coming Years (AutoRecovered)Document6 pagesThe Role of Information Technology in Pharmacy Practice Is Dynamic and Not Likely To Lose Relevance in The Coming Years (AutoRecovered)masresha teferaNo ratings yet

- Kruse2018 TheUseOfElectronicHealthRecordDocument16 pagesKruse2018 TheUseOfElectronicHealthRecordalNo ratings yet

- Hospital Pharmacy Supplement March 172015Document18 pagesHospital Pharmacy Supplement March 172015MoisesNo ratings yet

- Research Article Willingness To Pay For Social Health Insurance and Associated Factors Among Health Care Providers in Addis Ababa, EthiopiaDocument7 pagesResearch Article Willingness To Pay For Social Health Insurance and Associated Factors Among Health Care Providers in Addis Ababa, EthiopiaaisyahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 RRL (NEW UPDATE)Document7 pagesChapter 2 RRL (NEW UPDATE)kieferdoctor043No ratings yet

- Group 01: Articles For ReviewDocument4 pagesGroup 01: Articles For ReviewPrincess Krenzelle BañagaNo ratings yet

- HCI 540 Final PaperDocument10 pagesHCI 540 Final PaperJulian CorralNo ratings yet

- 25 - Healthcare Information SystemsDocument8 pages25 - Healthcare Information SystemsDon FabloNo ratings yet

- Shazu File - 044944Document9 pagesShazu File - 044944shabnumshowkat58No ratings yet

- Tizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Document4 pagesTizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Royce Vincent TizonNo ratings yet

- Identifying A Medical Department Based On Unstruct PDFDocument13 pagesIdentifying A Medical Department Based On Unstruct PDFShanu KabeerNo ratings yet

- Benefits - and - Challenges - of - Ele 6Document7 pagesBenefits - and - Challenges - of - Ele 6silfianaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Non Computerization of Patient's RecordsDocument66 pagesEffects of Non Computerization of Patient's RecordsDaniel ObasiNo ratings yet

- Patient Information Systems in The LiteratureDocument6 pagesPatient Information Systems in The LiteratureJohn MunaonyediNo ratings yet

- State Success Spurs National Innovation in Health Information Exchanges - Shared HealthDocument6 pagesState Success Spurs National Innovation in Health Information Exchanges - Shared Healthlisarx5No ratings yet

- HIS EnglishDocument53 pagesHIS Englishkgg1987No ratings yet

- Moroccan Electronic Health Record System: Houssam BENBRAHIM, Hanaâ HACHIMI and Aouatif AMINEDocument8 pagesMoroccan Electronic Health Record System: Houssam BENBRAHIM, Hanaâ HACHIMI and Aouatif AMINESouhaïla MOUMOUNo ratings yet

- Case 2 - Business Case Data Chaos Creates RiskDocument3 pagesCase 2 - Business Case Data Chaos Creates RiskM. WildanNo ratings yet

- Project ProposalDocument9 pagesProject ProposalMike Mwesh BernardNo ratings yet

- EMR ManuscriptDocument20 pagesEMR ManuscriptGetahun TekleNo ratings yet

- Journal VeteranDocument12 pagesJournal VeteranChairani Surya UtamiNo ratings yet

- Emr Ehr 09Document6 pagesEmr Ehr 09savvy_as_98-1No ratings yet

- gjmbsv3n3spl 14Document25 pagesgjmbsv3n3spl 14areeb khanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 24 - Pharmacy Informatics - Enabling Safe and Efficacious Medication UseDocument15 pagesChapter 24 - Pharmacy Informatics - Enabling Safe and Efficacious Medication UseMirghaniIsmailMeMooNo ratings yet

- HealthcareDocument8 pagesHealthcareAnas BilalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 5Document43 pagesChapter 1 5YueReshaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Attitude of Health Workers in State Hospitals, Towards Information TechnologyDocument49 pagesKnowledge and Attitude of Health Workers in State Hospitals, Towards Information TechnologyTajudeen AdegbenroNo ratings yet

- Digital Health PaymentDocument5 pagesDigital Health PaymentGetu ZerihunNo ratings yet

- Mhealth ReportDocument101 pagesMhealth ReportSteveEpsteinNo ratings yet

- ACIS2004final v4Document6 pagesACIS2004final v4noina abinarNo ratings yet

- Hcin 540 EssayDocument14 pagesHcin 540 Essayapi-408487557No ratings yet

- Health Care Innovations EssayDocument6 pagesHealth Care Innovations EssaySreejith BalachandranNo ratings yet

- Jurnal TugasDocument11 pagesJurnal TugasFadli NanlohyNo ratings yet

- Matic Pablo Pantig Patungan Peralta Nursing Informatics Final Requirement Conduct of Research Writing Thru Scoping ReviewDocument11 pagesMatic Pablo Pantig Patungan Peralta Nursing Informatics Final Requirement Conduct of Research Writing Thru Scoping ReviewYuuki Chitose (tai-kun)No ratings yet

- Patient Record Management Information Sy2222Document7 pagesPatient Record Management Information Sy2222Innovator AdrianNo ratings yet

- Health Systems Improving and Sustaining Quality Through Digital TransformationDocument5 pagesHealth Systems Improving and Sustaining Quality Through Digital TransformationAnonymous 3Et8A0CuCNo ratings yet

- Health informatics: Improving patient careFrom EverandHealth informatics: Improving patient careBCS, The Chartered Institute for ITRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Fifth Circuit Obamacare RulingDocument98 pagesFifth Circuit Obamacare RulingLaw&CrimeNo ratings yet

- DOJ Argues Entire ACA Should Fall in Fifth Circuit Brief - May 2019Document75 pagesDOJ Argues Entire ACA Should Fall in Fifth Circuit Brief - May 2019HLMeditNo ratings yet

- House Motion To Intervene in ACA Lawsuit, Fifth CircuitDocument33 pagesHouse Motion To Intervene in ACA Lawsuit, Fifth CircuitHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Texas. Et Al v. U.S. Et Al OpinionDocument55 pagesTexas. Et Al v. U.S. Et Al OpinionDoug MataconisNo ratings yet

- Complaint Challenging Site Neutral Payment Policy181204Document22 pagesComplaint Challenging Site Neutral Payment Policy181204Jesse MajorNo ratings yet

- ACA Lawsuit Put On Hold Over Government ShutdownDocument3 pagesACA Lawsuit Put On Hold Over Government ShutdownHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Intermountain To Seek Writ SCOTUSDocument9 pagesIntermountain To Seek Writ SCOTUSHLMedit100% (1)

- Reforming America's Healthcare System Through Choice and CompetitionDocument119 pagesReforming America's Healthcare System Through Choice and CompetitionHLMeditNo ratings yet

- CHS Subsidiary HMA Reaches $260 Million Settlement Over Billing PracticesDocument68 pagesCHS Subsidiary HMA Reaches $260 Million Settlement Over Billing PracticesHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Letter of Support For ACOs and MSSP NPRM Sign On 09202018Document3 pagesLetter of Support For ACOs and MSSP NPRM Sign On 09202018HLMeditNo ratings yet

- Maine Attorney General ACA Lawsuit 837384fb 1155 4ac6 Ad98 5f4c18fd2e4aDocument5 pagesMaine Attorney General ACA Lawsuit 837384fb 1155 4ac6 Ad98 5f4c18fd2e4aHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Jury Awards $50M in NorthShore Health Malpractice SuitDocument23 pagesJury Awards $50M in NorthShore Health Malpractice SuitHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Hospitals Sue HHS Over 340BDocument19 pagesHospitals Sue HHS Over 340BHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Lawsuit To Stipulate Terms of CVS-Aetna MergerDocument19 pagesLawsuit To Stipulate Terms of CVS-Aetna MergerHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Cigna Reiterates Support For Proposed Merger With Express ScriptsDocument9 pagesCigna Reiterates Support For Proposed Merger With Express ScriptsHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Next Generation ACOs - First Annual ReportDocument2 pagesNext Generation ACOs - First Annual ReportHLMeditNo ratings yet

- States Suing Trump Administration Over Association Health Plans Seek Quick WinDocument68 pagesStates Suing Trump Administration Over Association Health Plans Seek Quick WinHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Medicare To Eliminate Appeals Backlog Within 4 Years, HHS Tells JudgeDocument30 pagesMedicare To Eliminate Appeals Backlog Within 4 Years, HHS Tells JudgeHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Doctors Sue Anthem Over 'Dangerous' ER Coverage PolicyDocument48 pagesDoctors Sue Anthem Over 'Dangerous' ER Coverage PolicyHLMeditNo ratings yet

- More Hospitals Sue HHS Over DSH Payment CalculationsDocument19 pagesMore Hospitals Sue HHS Over DSH Payment CalculationsHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Indictment: Anthem Fraud Investigator Arrested in Fraud InvestigationDocument13 pagesIndictment: Anthem Fraud Investigator Arrested in Fraud InvestigationHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Sonja Emery: Detention Hearing AppealDocument32 pagesSonja Emery: Detention Hearing AppealHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Moda RulingDocument55 pagesModa RulingElizabeth HayesNo ratings yet

- GeroDocument7 pagesGeroJehanie LukmanNo ratings yet

- Medical Attendance and Treatment - 601.: Section A DefinitionsDocument1 pageMedical Attendance and Treatment - 601.: Section A DefinitionsHari GuptaNo ratings yet

- Daftar Obat Yang Aman Bagi Ibu HamilDocument14 pagesDaftar Obat Yang Aman Bagi Ibu HamilIcha Marisa LanaNo ratings yet

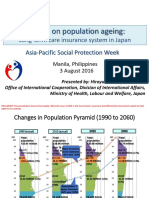

- APSP - Session 9A - Hiroyuki Yamaya - MHLWDocument8 pagesAPSP - Session 9A - Hiroyuki Yamaya - MHLWKristine PresbiteroNo ratings yet

- Deviation in Pharma: What Is A DeviationDocument2 pagesDeviation in Pharma: What Is A DeviationAshok KumarNo ratings yet

- Diclegis Full Prescribing InformationDocument12 pagesDiclegis Full Prescribing Informationks2No ratings yet

- War RoomDocument35 pagesWar RoomAnkit VarshneyNo ratings yet

- The Bipolar II Depression Questionnaire: A Self-Report Tool For Detecting Bipolar II DepressionDocument16 pagesThe Bipolar II Depression Questionnaire: A Self-Report Tool For Detecting Bipolar II DepressionMaya Putri HaryantiNo ratings yet

- Adult Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes PDFDocument39 pagesAdult Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes PDFrosythapaNo ratings yet

- Personality DisorderDocument15 pagesPersonality DisorderDherick RosasNo ratings yet

- Aortopulmonary Window in InfantsDocument3 pagesAortopulmonary Window in Infantsonlyjust4meNo ratings yet

- Literature Study On Hospital DesignDocument17 pagesLiterature Study On Hospital DesignVenkat100% (3)

- Dr. Trunojoyo, SPS Stroke - The Rational Management of Stroke PDFDocument37 pagesDr. Trunojoyo, SPS Stroke - The Rational Management of Stroke PDFrizkhameiliaNo ratings yet

- Sample - Chapter 48 - Treatment of Periodontal AbscessDocument8 pagesSample - Chapter 48 - Treatment of Periodontal AbscessMuhammad Faiz Iqbal ARNo ratings yet

- CT BTDocument20 pagesCT BTZainMalikNo ratings yet

- Restructuring of VHA Clinical ProgramsDocument10 pagesRestructuring of VHA Clinical ProgramsguaymasjimNo ratings yet

- Bad Blood The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment by James H. Jones 1981 Review by Francis HelminsiDocument5 pagesBad Blood The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment by James H. Jones 1981 Review by Francis HelminsiCitlalli Costilla LeyvaNo ratings yet

- Erectile Dysfunction: Management Update: Review SynthèseDocument9 pagesErectile Dysfunction: Management Update: Review SynthèseAditya Villas-BoasNo ratings yet

- Sukarmin - 2 PDFDocument7 pagesSukarmin - 2 PDFCitra PriyoNo ratings yet

- AxSOS-ST-30 StrykerDocument20 pagesAxSOS-ST-30 Strykeraditya permadiNo ratings yet

- Alzheimer's Disease Case StudyDocument5 pagesAlzheimer's Disease Case Studyjisoo100% (1)

- Tonsil and Adenoid Surgery: Frequently Asked QuestionsDocument4 pagesTonsil and Adenoid Surgery: Frequently Asked QuestionsfrabziNo ratings yet

- Acute Care Mid-Point Reflective Journal 2018Document2 pagesAcute Care Mid-Point Reflective Journal 2018api-430387359No ratings yet

- Cheat SheetDocument2 pagesCheat SheetglenNo ratings yet

- Listen To A Conversation Between A Nurse and A Patient. Choose The Correct AnswersDocument5 pagesListen To A Conversation Between A Nurse and A Patient. Choose The Correct Answersmiy500_542116704No ratings yet

- Folfiri Beva Gi Col PDocument12 pagesFolfiri Beva Gi Col Pvera docNo ratings yet

- General AnestheticsDocument6 pagesGeneral AnestheticsThulasi tootsie100% (1)

- CghsDocument74 pagesCghsanon-16877182% (11)

- Isolation in Restorative DentistryDocument49 pagesIsolation in Restorative DentistrySusan100% (1)

Commonwealth Fund EHR Survey

Commonwealth Fund EHR Survey

Uploaded by

HLMeditCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Commonwealth Fund EHR Survey

Commonwealth Fund EHR Survey

Uploaded by

HLMeditCopyright:

Available Formats

Issue Brief

MAY 2014

The Adoption and Use of

Health Information Technology by

Community Health Centers, 20092013

JAMIE RYAN, MICHELLE M. DOTY, MELINDA K. ABRAMS,

AND PAMELA RILEY

Abstract: With help from targeted federal investments, U.S. physician offices and hos-

pitals have accelerated their adoption and use of patient electronic health records (EHRs)

and other health information technology (HIT) in recent years. Comparison of results from

The Commonwealth Funds two national surveys of federally qualified health centers

(FQHCs) in 2009 and 2013 show that HIT adoption has also grown substantially for these

important providers of care in poor and underserved communities. Nearly all surveyed

FQHCs (93%) now have an EHR system, a 133 percent increase from 2009, the year fed-

eral meaningful use incentives for HIT were first authorized. Three-quarters of health

centers (76%) reported meeting the criteria to qualify for incentive payments. Remaining

challenges for health centers include achieving greater interoperability of EHR systems

and ensuring patient access to their records. Mobile technology, such as text messaging,

may help FQHCs further expand patient outreach and access to care.

OVERVIEW

Federally qualified health centers (FQHCs) provide comprehensive primary care,

behavioral health, dental care, and other services to all people, regardless of their

ability to pay or their health insurance status. First established in 1965, FQHCs

and their predecessors have expanded access to care for people in low-income

communities throughout the United States and reduced racial and ethnic health

disparities.

1

Since 2009, the federal government has provided community health

centers with unprecedented funding to help them build their health information

technology (HIT) infrastructure so they can provide more coordinated and effi-

cient care to an ever-growing patient population. Both the Health Information

Technology for Economic and Clinical Health Act of 2009 (HITECH) and the

Affordable Care Act (ACA) contain specific incentives and programs to foster

development of HIT systems and networks among FQHCs.

2,3

While national trends in physicians use of HIT have been well docu-

mented, less is known about the progress made by the nations health centers. We

To learn more about new publications

when they become available, visit the

Funds website and register to receive

email alerts.

Commonwealth Fund pub. 1746

Vol. 10

The mission of The Commonwealth

Fund is to promote a high performance

health care system. The Fund carries

out this mandate by supporting

independent research on health care

issues and making grants to improve

health care practice and policy. Support

for this research was provided by

The Commonwealth Fund. The views

presented here are those of the authors

and not necessarily those of The

Commonwealth Fund or its directors,

offcers, or staff.

For more information about this brief,

please contact:

Melinda K. Abrams, M.S.

Vice President

Health Care Delivery System Reform

The Commonwealth Fund

mka@cmwf.org

E M B A R G O E D

Not for release before

12:01 a.m. ET

Friday,

May 16, 2014

2 THE COMMONWEALTH FUND

examine data from The Commonwealth Funds two

national surveys of FQHCsthe first one conducted

in 2009, before enactment of the ACA and during the

very early stages of deployment of HITECH funds, and

the second in 2013to describe trends in HIT adoption

among FQHCs. (For information about the survey, see

How This Study Was Conducted on page 4.)

RESEARCH FINDINGS

The adoption of patient electronic health

records by federally qualified health

centers more than doubled between 2009

and 2013.

Over the period between the two surveys, the percent-

age of FQHCs establishing patient electronic health

record (EHR) systems more than doubled, from 40

percent to 93 percent (Exhibit 1). When asked about

the specific functionalities of EHR systems, the vast

majority of FQHCs reported they had systems to assist

providers with tracking information about all their

patients and managing their care. Nearly all FQHCs

have the ability to electronically generate information

about individual patients or a panel of patients, includ-

ing lists of patients by diagnosis (98%) and lab result

(90%), as well as a list of medications each patient is

taking (86%). The vast majority of FQHCs (82%) also

can generate a list of patients who are overdue for tests

or preventive care (Table 1).

Computerized provider order entry is also

widespread. About nine of 10 FQHCs can routinely

electronically prescribe medications (91%), enter clini-

cal notes (92%), and order (87%) and access (86%)

lab test results, and three-quarters can track test results

until they reach clinicians (77%). While use of elec-

tronic clinical decision support, a sophisticated HIT

component intended to reduce errors and adverse

events and increase efficiency, generally lags other

EHR functions, significant progress has been made

on this front as well: more than half (55%) of FQHCs

reported that their providers can receive electronic

alerts or prompts to provide patients with their test

results, nearly double the proportion reporting this in

2009 (28%).

Only 35 percent of health centers can electron-

ically send patients reminder notices for preventive or

follow-up care, the same percentage reported in 2009.

However, 83 percent said their HIT system can provide

alerts or prompts about potential problems with medi-

cation doses or drug interactions, up from 38 percent

in 2009.

A health center is considered to have advanced

HIT capacity if it can perform at least nine of 13 key

functions (Table 1). In the 2013 survey, 85 percent of

centers reported having between nine and 13 of these

functions, up from 30 percent in 2009 (Exhibit 1). Ten

percent reported having between four and eight func-

tions, and only 4 percent reported zero to three.

Exhibit 1. Trends in Health Information Technology Capacity

in Federally Qualifed Health Centers, 20092013

40

30

93

85

0

20

40

60

80

100

EHR system Advanced HIT functionality

Percent of centers reporting: 2009 2013

Source: The Commonwealth Fund 2013 and 2009 Surveys of Federally Qualifed Health Centers.

Notes: EHR = electronic health record. Advanced health information technology (HIT) functionality is defned as meeting at least

nine of 13 key functions.

THE ADOPTION AND USE OF HEALTH INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY BY COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS, 20092013 3

Rates of interoperability of EHR systems

and electronic access for patients are low.

More than three-quarters of the largest sites operated

by health centers have the ability to share lab results

(83%), imaging reports (76%), medication lists (80%),

and visit summaries (77%) electronically with other

providers within the health center organization (Table

2). However, far fewer sites reported such interoper-

ability outside the organization. No more than two of

five centers reported electronically sharing lab results

(41%), imaging reports (33%), medication lists (37%),

and visit summaries (34%) with external provid-

ers. Similarly, in only about one-third of centers can

patients view test results (33%), request appointments

or referrals (36%), or request prescription refills (34%)

through an online portal. And just one of 10 centers

allows patients to incorporate patient- or medical

device-generated data, such as daily blood glucose lev-

els, into their medical record (Table 2). A 2012 survey

of primary care physicians also found that electronic

patient access and health information exchange were

two of the least adopted EHR functions.

4

The majority of health centers qualify

for federal meaningful use incentive

payments.

Eighty-two percent of FQHCs have applied for the fed-

eral Meaningful Use Incentive Program, which rewards

providers who meet criteria for the delivery of care

using electronic health records (Table 3). More than

three-quarters (76%) of FQHCs reported that their pro-

viders have received incentive payments since 2011.

Stage 1 criteria, which emphasize data capture, include

actively using an EHR system to track key clinical

conditions and report information on clinical quality

measures; stage 2 criteria focus on advanced clinical

processes such as clinical decision support, as well as

more rigorous health information exchange between

providers.

5

Nearly all FQHCs (92%) reported that their

current EHR system meets at least stage 1 criteria, and

more than half (51%) said their system meets stage 2.

Just 2 percent of health centers meet neither stage 1 nor

stage 2 criteria (Table 3).

Adequacy of staff training and loss of

productivity are among the greatest

barriers to EHR adoption.

Although nearly all federally qualified health centers

use EHRs, the path to adoption has not always been

smooth. Centers reported that the greatest barriers to

EHR adoption were the adequacy of training for staff

(87%) and the loss of productivity during the transition

to an EHR system (86%), with 55 percent citing the

loss of productivity as a major barrier (Exhibit 2). Four

of five centers also reported that the annual cost of

maintaining an EHR system was a challenge, and that

Exhibit 2. Barriers to Electronic Health Record Adoption

Among Federally Qualifed Community Health Centers, 2013

36

44

55

36

44

36

31

51

0 20 40 60 80 100

Usefulness of templates for population

management

Annual cost of maintaining an EHR system

Loss of productivity during the transition

to an EHR system

Adequacy of training for your staff

Percentage of centers reporting the following barriers when using EHR systems:

Major barrier Minor barrier

87

86

80

80

Source: The Commonwealth Fund 2013 Survey of Federally Qualifed Health Centers.

4 THE COMMONWEALTH FUND

function as a national network of safety-net primary

care practices, enjoy a similar advantage.

The results of our study indicate a few areas

for improvement, however, some of which may be

addressed by current and future stages of the mean-

ingful-use incentive program. Interoperability across

multiple care settings and basic electronic patient

access have been prioritized in the programs second

stage. The third stage, still under development, may

highlight patients access to self-management tools and

comprehensive data through patient-centered health

information exchange.

10

Health centers ability to send

patients reminder notices for preventive or follow-up

care remains challenging as well. Moving forward,

reaching out to patients via mobile health technology,

such as text messaging, may be a promising strategy,

especially considering the higher rates of housing

instability among the low-income populations served

by FQHCs.

11

Clearly, targeted federal funding and incentives

have played a significant role in the widespread imple-

mentation of EHRs and advanced health information

systems by FQHCs. Health centers impressive adop-

tion of this technology bodes well for meeting not only

the needs of their existing patients but also those of the

millions of new patients expected as a result of national

health reform.

the templates for population management were often

barriers to EHR use. Only 1 percent of centers reported

that none of these were barriers to EHR adoption or

use (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Our survey research shows that the adoption of health

information technology by the nations federally quali-

fied health centers has increased tremendously since

targeted federal investments and meaningful-use incen-

tives were first authorized in 2009.

6

The rapid rate of

HIT adoption by FQHCs outpaces the rate of adoption

by office-based physicians78 percent of office-based

physicians used an electronic health record system in

2013, up from 48 percent in 2009.

7

A higher proportion

of FQHCs (93%) have an EHR system compared with

both larger practices and integrated delivery systems

(78% and 71%, respectively).

8

Moreover, three-quarters of health centers

reported having met federal meaningful-use criteria, a

proportion similar to that seen for large, non-physician-

owned medical practices and integrated systems.

9

Such practices and systems are likely better prepared

than solo or small physician-owned practices to make

the initial transition from paper-based record-keeping

and to leverage the benefits of HIT. It may well be the

case that FQHCs, which as part of a federal program

HOW THIS STUDY WAS CONDUCTED

The Commonwealth Fund 2013 Survey of Federally Qualified Health Centers was conducted by Social Science

Research Solutions from June 19, 2013, through October 24, 2013, among a nationally representative sample of

679 executive directors or clinical directors at federally qualified health centers (FQHCs). The survey sample was

drawn from a list of all FQHCs in 2011 that have at least one site that is a community-based primary care clinic.

The list was provided by the federal Bureau of Primary Health Care.

All 1,128 FQHCs were sent the questionnaire and 679 responded, yielding a response rate of 60 percent.

The survey consisted of a 12-page questionnaire that took approximately 20 to 25 minutes to complete.

Data were weighted by number of patients, number of sites, geographic region, and urban/rural location

to reflect the universe of primary care community centers as accurately as possible.

THE ADOPTION AND USE OF HEALTH INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY BY COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS, 20092013 5

NOTES

1

L. Shi, L. A. Lebrun, J. Zhu et al., Clinical Quality

Performance in U.S. Health Centers, Health

Services Research, May 2012 47(6):222549.

2

Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010

(P.L. 111-148, March 23, 2010).

3

American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009

(P.L. 111-5, Feb. 17, 2009).

4

A.-M. J. Audet, D. Squires, and M. M. Doty,

Where Are We on the Diffusion Curve? Trends and

Drivers of Primary Care Physicians Use of Health

Information Technology, Health Services Research,

Feb. 2014 49(1 Pt. 2):34760.

5

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, How

to Attain Meaningful Use, http://www.healthit.gov/

providers-professionals/how-attain-meaningful-use.

6

C. J. Hsiao and E. Hing, Use and Characteristics of

Electronic Health Record Systems Among Office-

Based Physician Practices: United States, 2001

2013, NCHS Data Brief, No. 143 (Hyattsville, Md.:

National Center for Health Statistics, Jan. 2014),

http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db143.pdf.

7

Ibid.

8

M. Crane. Solo and Small Practices Increase EHR

Adoption, Survey Finds, MedScape, March 26,

2014.

9

C. J. Hsiao, S. Decker, E. Hing et al., Most

Physicians Were Eligible for Federal Incentives

in 2011, But Few Had EHR Systems That Met

Meaningful Use Criteria, Health Affairs, May 2012

31(5):11007.

10

CMS, How to Attain Meaningful Use.

11

R. Cohen and K. Wardrip, Should I Stay or Should

I Go? Exploring the Effects of Housing Instability

and Mobility on Children (Washington, D.C.: Center

for Housing Policy, Feb. 2011).

6 THE COMMONWEALTH FUND

Table 1. Trends in Health Information Technology Adoption

Among Federally Qualifed Health Centers, 20092013

Total 2009 Total 2013 Absolute change Relative change

Percent Distribution 100% 100%

Unweighted n 795 679

1. Currently using EHRs 40 93 53 133%

Ability to generate patient and panel information electronically:

2. Can generate list of patients by diagnosis 80 98 18 23%

3. Can generate list of patients by lab result 59 90 31 53%

4. Can generate list of patients overdue for tests or preventive care 46 82 35 74%

5. Routinely use electronic lists of medications taken by a patient 38 86 48 126%

Computerized order entry management:

6. Routinely order lab tests electronically 45 87 42 93%

7. Routinely prescribe medication electronically 35 91 56 160%

8. Electronically track all lab tests until results reach clinicians 36 77 41 114%

9. Routinely electronically enter clinical notes, including medical history

and follow-up notes

38 92 53 136%

10. Routinely electronically access patients lab results 57 86 29 51%

Computerized decision support:

11. Providers receive alerts or prompts to provide patients with test results 28 55 27 96%

12. Providers routinely receive electronic alerts or prompts about potential

dose/drug interaction

38 83 45 118%

13. Patients sent reminder notices for regular preventive or follow-up care 34 35 1 3%

Advanced HIT capacity:

Low (03 of the above items) 39 4 34 89%

Medium (48 of the above items) 31 10 22 69%

High (913 of the above items) 30 85 55 183%

Sources: The Commonwealth Fund 2009 and 2013 Surveys of Federally Qualifed Health Centers.

THE ADOPTION AND USE OF HEALTH INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY BY COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS, 20092013 7

Table 2. Interoperability of Electronic Health Record Systems and Patient Access

Total 2013

Percent Distribution 100%

Unweighted n 679

Largest site can electronically share the following data with other providers:

Lab results

Within the health center organization 83

Outside the health center organization 41

Imaging reports

Within the health center organization 76

Outside the health center organization 33

Medication lists

Within the health center organization 80

Outside the health center organization 37

Visit summaries

Within the health center organization 77

Outside the health center organization 34

Patients have online access to:

View test results 33

Request appointments or referrals 36

Incorporate patient generated/device data 11

Request prescription reflls 34

Source: The Commonwealth Fund 2013 Survey of Federally Qualifed Health Centers.

Table 3. Meaningful Use of Health Information Technology

in Federally Qualifed Health Centers

Total 2013

Percent Distribution 100%

Unweighted n 679

Meets meaningful use criteria:

Stage 1 41

Stage 2 51

Neither 2

Applied to meaningful use incentive program:

Yes, already applied 82

Yes, plan to apply 11

Uncertain 3

No, will not apply 2

Received meaningful use incentives:

2011 42

2012 79

2013 56*

Any year 76

* Through October 2013.

Source: The Commonwealth Fund 2013 Survey of Federally Qualifed Health Centers.

8 THE COMMONWEALTH FUND

Table 4. Barriers to Electronic Health Record Usage

Among Federally Qualifed Health Centers

Total 2013

Percent Distribution 100%

Unweighted n 679

Barriers to EHR adoption:

Annual cost of maintaining an EHR system

Major barrier 44

Minor barrier 36

Not a barrier 17

Usefulness of templates for population management

Major barrier 36

Minor barrier 44

Not a barrier 17

Adequacy of training for your staff

Major barrier 36

Minor barrier 51

Not a barrier 11

Loss of productivity during the transition to an EHR system

Major barrier 55

Minor barrier 31

Not a barrier 11

Any of the above

Major barrier 78

Minor barrier 81

Major or minor barrier 96

Not a barrier 1

Source: The Commonwealth Fund 2013 Survey of Federally Qualifed Health Centers.

THE ADOPTION AND USE OF HEALTH INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY BY COMMUNITY HEALTH CENTERS, 20092013 9

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Jamie Ryan, M.P.H., is a program associate for the Health Care Delivery System Reform program. She was

the primary analyst of the Commonwealth Fund 2013 Survey of Federally Qualified Health Centers. Ms. Ryan

joined the Fund soon after receiving her masters degree from Columbia University. Prior to graduate school,

she held internships at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the U.S. General Services

Administration. Ms. Ryan received a B.S. in Biopsychology from Tufts University in 2010, and an M.P.H. in

Health Policy from Columbia Universitys Mailman School of Public Health in 2013.

Michelle McEvoy Doty, Ph.D., is vice president of survey research and evaluation for The Commonwealth Fund.

She has authored numerous publications on cross-national comparisons of health system performance, access

to quality health care among vulnerable populations, and the extent to which lack of health insurance contrib-

utes to inequities in quality of care. She received her M.P.H. and Ph.D. in public health from the University of

California, Los Angeles.

Melinda K. Abrams, M.S., is a vice president of The Commonwealth Funds Health Care Delivery System

Reform program. Since coming to the Fund in 1997, Ms. Abrams has worked on the Funds Task Force on

Academic Health Centers, the Commission on Womens Health, and, most recently, the Child Development and

Preventive Care program. She serves on the board of managers of TransforMED, the steering committee for the

American Board of Internal Medicines Team-Based Care Task Force, and three expert panels for the Agency for

Healthcare Research and Qualitys Primary Care Transformation Initiative, and is a peer reviewer for the Annals

of Family Medicine. Ms. Abrams holds an M.S. in health policy and management from the Harvard School of

Public Health.

Pamela Riley, M.D., M.P.H., is assistant vice president for The Commonwealth Funds Health Care Delivery

System Reform program. Dr. Riley is a pediatrician with a longstanding commitment to improving the health

of low-income, medically underserved populations. She was previously program officer at the New York State

Health Foundation. Earlier in her career, Dr. Riley served as clinical instructor in the Division of General

Pediatrics at the Stanford University School of Medicine. She served as a Duke University Sanford School of

Public Policy Global Health Policy Fellow at the World Health Organization in Geneva, Switzerland, and has

served as a volunteer physician in Peru and Guatemala. Dr. Riley received her medical degree from the UCLA

David Geffen School of Medicine in 2000, and completed her internship and residency in pediatrics at Harbor-

UCLA Medical Center in Torrance, Calif., in 2003. Dr. Riley received an M.P.H. from the Harvard School of

Public Health as a Commonwealth Fund/Harvard University Minority Health Policy Fellow in 2009.

Editorial support was provided by Chris Hollander.

www.commonweal thfund.org

You might also like

- Benefits of Iclinicsys in The Rural Health Unit of Lupi, Camarines SurDocument5 pagesBenefits of Iclinicsys in The Rural Health Unit of Lupi, Camarines Surattyleoimperial100% (1)

- Case Study 1Document3 pagesCase Study 1Dwaine TolentinoNo ratings yet

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument6 pagesReview of Related LiteratureSkyla FiestaNo ratings yet

- Case 1-2 Business Case Data Chaos Creates RiskDocument5 pagesCase 1-2 Business Case Data Chaos Creates RiskfauziahezzyNo ratings yet

- AMA Letter To DOJ Regarding CVS Aetna MergerDocument141 pagesAMA Letter To DOJ Regarding CVS Aetna MergerHLMedit100% (1)

- OSF HealthCare Prevails in Dispute Over Church PlanDocument16 pagesOSF HealthCare Prevails in Dispute Over Church PlanHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Hammer Plea AgreementDocument31 pagesHammer Plea AgreementHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Pfizer Corporate Integrity Agreement (HHS OIG)Document53 pagesPfizer Corporate Integrity Agreement (HHS OIG)HLMeditNo ratings yet

- What Is Computer ApplicationsDocument6 pagesWhat Is Computer ApplicationsElle7loboNo ratings yet

- Article 3Document12 pagesArticle 3مالك مناصرةNo ratings yet

- Hit Research ProjectDocument20 pagesHit Research ProjectDavid JuarezNo ratings yet

- Order ### 2672790Document11 pagesOrder ### 2672790Wallace Mandela Ong'ayoNo ratings yet

- E PrescribingDocument6 pagesE Prescribingapi-326037307No ratings yet

- Term Paper Complete DraftDocument16 pagesTerm Paper Complete Draftapi-464597952No ratings yet

- Role of Healthcare Law in Regards To InformaticsDocument8 pagesRole of Healthcare Law in Regards To InformaticsTimothyCLentzJr.100% (1)

- 73 Integration2010 ProceedingsDocument9 pages73 Integration2010 ProceedingsKhirulnizam Abd RahmanNo ratings yet

- Tizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Document4 pagesTizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Royce Vincent TizonNo ratings yet

- Hospitals and Health Networks Magazine's 2015 Most WiredDocument15 pagesHospitals and Health Networks Magazine's 2015 Most WiredWatertown Daily TimesNo ratings yet

- Business Case: Data Chaos Creates RiskDocument3 pagesBusiness Case: Data Chaos Creates RiskRizka DestianaNo ratings yet

- Issues in International Health Policy: Electronic Health Records: An International Perspective On "Meaningful Use"Document18 pagesIssues in International Health Policy: Electronic Health Records: An International Perspective On "Meaningful Use"Sevi Cephy ONo ratings yet

- HMODocument8 pagesHMOrunass_07No ratings yet

- Tihp It 012610Document7 pagesTihp It 012610api-258667648No ratings yet

- Hcin 540 - Term PaperDocument16 pagesHcin 540 - Term Paperapi-428767663No ratings yet

- 5 Benefits of Technology in HealthcareDocument2 pages5 Benefits of Technology in HealthcareCHUAH TZE YEE MoeNo ratings yet

- Hesr 53 3270Document8 pagesHesr 53 3270Kyle Isidro MaleNo ratings yet

- Nkrouse Revanthgurram Jiqinli Shanniwu Xinyizhang White PaperDocument9 pagesNkrouse Revanthgurram Jiqinli Shanniwu Xinyizhang White Paperapi-247217685No ratings yet

- According To JMIR PublicationsDocument3 pagesAccording To JMIR PublicationsJanine KhoNo ratings yet

- Final Final HSM PaperDocument20 pagesFinal Final HSM PaperJamie JacksonNo ratings yet

- The Role of Information Technology in Pharmacy Practice Is Dynamic and Not Likely To Lose Relevance in The Coming Years (AutoRecovered)Document6 pagesThe Role of Information Technology in Pharmacy Practice Is Dynamic and Not Likely To Lose Relevance in The Coming Years (AutoRecovered)masresha teferaNo ratings yet

- Kruse2018 TheUseOfElectronicHealthRecordDocument16 pagesKruse2018 TheUseOfElectronicHealthRecordalNo ratings yet

- Hospital Pharmacy Supplement March 172015Document18 pagesHospital Pharmacy Supplement March 172015MoisesNo ratings yet

- Research Article Willingness To Pay For Social Health Insurance and Associated Factors Among Health Care Providers in Addis Ababa, EthiopiaDocument7 pagesResearch Article Willingness To Pay For Social Health Insurance and Associated Factors Among Health Care Providers in Addis Ababa, EthiopiaaisyahNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 RRL (NEW UPDATE)Document7 pagesChapter 2 RRL (NEW UPDATE)kieferdoctor043No ratings yet

- Group 01: Articles For ReviewDocument4 pagesGroup 01: Articles For ReviewPrincess Krenzelle BañagaNo ratings yet

- HCI 540 Final PaperDocument10 pagesHCI 540 Final PaperJulian CorralNo ratings yet

- 25 - Healthcare Information SystemsDocument8 pages25 - Healthcare Information SystemsDon FabloNo ratings yet

- Shazu File - 044944Document9 pagesShazu File - 044944shabnumshowkat58No ratings yet

- Tizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Document4 pagesTizon, R. - Assignment in NCM 112Royce Vincent TizonNo ratings yet

- Identifying A Medical Department Based On Unstruct PDFDocument13 pagesIdentifying A Medical Department Based On Unstruct PDFShanu KabeerNo ratings yet

- Benefits - and - Challenges - of - Ele 6Document7 pagesBenefits - and - Challenges - of - Ele 6silfianaNo ratings yet

- Effects of Non Computerization of Patient's RecordsDocument66 pagesEffects of Non Computerization of Patient's RecordsDaniel ObasiNo ratings yet

- Patient Information Systems in The LiteratureDocument6 pagesPatient Information Systems in The LiteratureJohn MunaonyediNo ratings yet

- State Success Spurs National Innovation in Health Information Exchanges - Shared HealthDocument6 pagesState Success Spurs National Innovation in Health Information Exchanges - Shared Healthlisarx5No ratings yet

- HIS EnglishDocument53 pagesHIS Englishkgg1987No ratings yet

- Moroccan Electronic Health Record System: Houssam BENBRAHIM, Hanaâ HACHIMI and Aouatif AMINEDocument8 pagesMoroccan Electronic Health Record System: Houssam BENBRAHIM, Hanaâ HACHIMI and Aouatif AMINESouhaïla MOUMOUNo ratings yet

- Case 2 - Business Case Data Chaos Creates RiskDocument3 pagesCase 2 - Business Case Data Chaos Creates RiskM. WildanNo ratings yet

- Project ProposalDocument9 pagesProject ProposalMike Mwesh BernardNo ratings yet

- EMR ManuscriptDocument20 pagesEMR ManuscriptGetahun TekleNo ratings yet

- Journal VeteranDocument12 pagesJournal VeteranChairani Surya UtamiNo ratings yet

- Emr Ehr 09Document6 pagesEmr Ehr 09savvy_as_98-1No ratings yet

- gjmbsv3n3spl 14Document25 pagesgjmbsv3n3spl 14areeb khanNo ratings yet

- Chapter 24 - Pharmacy Informatics - Enabling Safe and Efficacious Medication UseDocument15 pagesChapter 24 - Pharmacy Informatics - Enabling Safe and Efficacious Medication UseMirghaniIsmailMeMooNo ratings yet

- HealthcareDocument8 pagesHealthcareAnas BilalNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 5Document43 pagesChapter 1 5YueReshaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge and Attitude of Health Workers in State Hospitals, Towards Information TechnologyDocument49 pagesKnowledge and Attitude of Health Workers in State Hospitals, Towards Information TechnologyTajudeen AdegbenroNo ratings yet

- Digital Health PaymentDocument5 pagesDigital Health PaymentGetu ZerihunNo ratings yet

- Mhealth ReportDocument101 pagesMhealth ReportSteveEpsteinNo ratings yet

- ACIS2004final v4Document6 pagesACIS2004final v4noina abinarNo ratings yet

- Hcin 540 EssayDocument14 pagesHcin 540 Essayapi-408487557No ratings yet

- Health Care Innovations EssayDocument6 pagesHealth Care Innovations EssaySreejith BalachandranNo ratings yet

- Jurnal TugasDocument11 pagesJurnal TugasFadli NanlohyNo ratings yet

- Matic Pablo Pantig Patungan Peralta Nursing Informatics Final Requirement Conduct of Research Writing Thru Scoping ReviewDocument11 pagesMatic Pablo Pantig Patungan Peralta Nursing Informatics Final Requirement Conduct of Research Writing Thru Scoping ReviewYuuki Chitose (tai-kun)No ratings yet

- Patient Record Management Information Sy2222Document7 pagesPatient Record Management Information Sy2222Innovator AdrianNo ratings yet

- Health Systems Improving and Sustaining Quality Through Digital TransformationDocument5 pagesHealth Systems Improving and Sustaining Quality Through Digital TransformationAnonymous 3Et8A0CuCNo ratings yet

- Health informatics: Improving patient careFrom EverandHealth informatics: Improving patient careBCS, The Chartered Institute for ITRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Fifth Circuit Obamacare RulingDocument98 pagesFifth Circuit Obamacare RulingLaw&CrimeNo ratings yet

- DOJ Argues Entire ACA Should Fall in Fifth Circuit Brief - May 2019Document75 pagesDOJ Argues Entire ACA Should Fall in Fifth Circuit Brief - May 2019HLMeditNo ratings yet

- House Motion To Intervene in ACA Lawsuit, Fifth CircuitDocument33 pagesHouse Motion To Intervene in ACA Lawsuit, Fifth CircuitHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Texas. Et Al v. U.S. Et Al OpinionDocument55 pagesTexas. Et Al v. U.S. Et Al OpinionDoug MataconisNo ratings yet

- Complaint Challenging Site Neutral Payment Policy181204Document22 pagesComplaint Challenging Site Neutral Payment Policy181204Jesse MajorNo ratings yet

- ACA Lawsuit Put On Hold Over Government ShutdownDocument3 pagesACA Lawsuit Put On Hold Over Government ShutdownHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Intermountain To Seek Writ SCOTUSDocument9 pagesIntermountain To Seek Writ SCOTUSHLMedit100% (1)

- Reforming America's Healthcare System Through Choice and CompetitionDocument119 pagesReforming America's Healthcare System Through Choice and CompetitionHLMeditNo ratings yet

- CHS Subsidiary HMA Reaches $260 Million Settlement Over Billing PracticesDocument68 pagesCHS Subsidiary HMA Reaches $260 Million Settlement Over Billing PracticesHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Letter of Support For ACOs and MSSP NPRM Sign On 09202018Document3 pagesLetter of Support For ACOs and MSSP NPRM Sign On 09202018HLMeditNo ratings yet

- Maine Attorney General ACA Lawsuit 837384fb 1155 4ac6 Ad98 5f4c18fd2e4aDocument5 pagesMaine Attorney General ACA Lawsuit 837384fb 1155 4ac6 Ad98 5f4c18fd2e4aHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Jury Awards $50M in NorthShore Health Malpractice SuitDocument23 pagesJury Awards $50M in NorthShore Health Malpractice SuitHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Hospitals Sue HHS Over 340BDocument19 pagesHospitals Sue HHS Over 340BHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Lawsuit To Stipulate Terms of CVS-Aetna MergerDocument19 pagesLawsuit To Stipulate Terms of CVS-Aetna MergerHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Cigna Reiterates Support For Proposed Merger With Express ScriptsDocument9 pagesCigna Reiterates Support For Proposed Merger With Express ScriptsHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Next Generation ACOs - First Annual ReportDocument2 pagesNext Generation ACOs - First Annual ReportHLMeditNo ratings yet

- States Suing Trump Administration Over Association Health Plans Seek Quick WinDocument68 pagesStates Suing Trump Administration Over Association Health Plans Seek Quick WinHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Medicare To Eliminate Appeals Backlog Within 4 Years, HHS Tells JudgeDocument30 pagesMedicare To Eliminate Appeals Backlog Within 4 Years, HHS Tells JudgeHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Doctors Sue Anthem Over 'Dangerous' ER Coverage PolicyDocument48 pagesDoctors Sue Anthem Over 'Dangerous' ER Coverage PolicyHLMeditNo ratings yet

- More Hospitals Sue HHS Over DSH Payment CalculationsDocument19 pagesMore Hospitals Sue HHS Over DSH Payment CalculationsHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Indictment: Anthem Fraud Investigator Arrested in Fraud InvestigationDocument13 pagesIndictment: Anthem Fraud Investigator Arrested in Fraud InvestigationHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Sonja Emery: Detention Hearing AppealDocument32 pagesSonja Emery: Detention Hearing AppealHLMeditNo ratings yet

- Moda RulingDocument55 pagesModa RulingElizabeth HayesNo ratings yet

- GeroDocument7 pagesGeroJehanie LukmanNo ratings yet

- Medical Attendance and Treatment - 601.: Section A DefinitionsDocument1 pageMedical Attendance and Treatment - 601.: Section A DefinitionsHari GuptaNo ratings yet

- Daftar Obat Yang Aman Bagi Ibu HamilDocument14 pagesDaftar Obat Yang Aman Bagi Ibu HamilIcha Marisa LanaNo ratings yet

- APSP - Session 9A - Hiroyuki Yamaya - MHLWDocument8 pagesAPSP - Session 9A - Hiroyuki Yamaya - MHLWKristine PresbiteroNo ratings yet

- Deviation in Pharma: What Is A DeviationDocument2 pagesDeviation in Pharma: What Is A DeviationAshok KumarNo ratings yet

- Diclegis Full Prescribing InformationDocument12 pagesDiclegis Full Prescribing Informationks2No ratings yet

- War RoomDocument35 pagesWar RoomAnkit VarshneyNo ratings yet

- The Bipolar II Depression Questionnaire: A Self-Report Tool For Detecting Bipolar II DepressionDocument16 pagesThe Bipolar II Depression Questionnaire: A Self-Report Tool For Detecting Bipolar II DepressionMaya Putri HaryantiNo ratings yet

- Adult Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes PDFDocument39 pagesAdult Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes PDFrosythapaNo ratings yet

- Personality DisorderDocument15 pagesPersonality DisorderDherick RosasNo ratings yet

- Aortopulmonary Window in InfantsDocument3 pagesAortopulmonary Window in Infantsonlyjust4meNo ratings yet

- Literature Study On Hospital DesignDocument17 pagesLiterature Study On Hospital DesignVenkat100% (3)

- Dr. Trunojoyo, SPS Stroke - The Rational Management of Stroke PDFDocument37 pagesDr. Trunojoyo, SPS Stroke - The Rational Management of Stroke PDFrizkhameiliaNo ratings yet

- Sample - Chapter 48 - Treatment of Periodontal AbscessDocument8 pagesSample - Chapter 48 - Treatment of Periodontal AbscessMuhammad Faiz Iqbal ARNo ratings yet

- CT BTDocument20 pagesCT BTZainMalikNo ratings yet

- Restructuring of VHA Clinical ProgramsDocument10 pagesRestructuring of VHA Clinical ProgramsguaymasjimNo ratings yet

- Bad Blood The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment by James H. Jones 1981 Review by Francis HelminsiDocument5 pagesBad Blood The Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment by James H. Jones 1981 Review by Francis HelminsiCitlalli Costilla LeyvaNo ratings yet

- Erectile Dysfunction: Management Update: Review SynthèseDocument9 pagesErectile Dysfunction: Management Update: Review SynthèseAditya Villas-BoasNo ratings yet

- Sukarmin - 2 PDFDocument7 pagesSukarmin - 2 PDFCitra PriyoNo ratings yet

- AxSOS-ST-30 StrykerDocument20 pagesAxSOS-ST-30 Strykeraditya permadiNo ratings yet

- Alzheimer's Disease Case StudyDocument5 pagesAlzheimer's Disease Case Studyjisoo100% (1)

- Tonsil and Adenoid Surgery: Frequently Asked QuestionsDocument4 pagesTonsil and Adenoid Surgery: Frequently Asked QuestionsfrabziNo ratings yet

- Acute Care Mid-Point Reflective Journal 2018Document2 pagesAcute Care Mid-Point Reflective Journal 2018api-430387359No ratings yet

- Cheat SheetDocument2 pagesCheat SheetglenNo ratings yet

- Listen To A Conversation Between A Nurse and A Patient. Choose The Correct AnswersDocument5 pagesListen To A Conversation Between A Nurse and A Patient. Choose The Correct Answersmiy500_542116704No ratings yet

- Folfiri Beva Gi Col PDocument12 pagesFolfiri Beva Gi Col Pvera docNo ratings yet

- General AnestheticsDocument6 pagesGeneral AnestheticsThulasi tootsie100% (1)

- CghsDocument74 pagesCghsanon-16877182% (11)

- Isolation in Restorative DentistryDocument49 pagesIsolation in Restorative DentistrySusan100% (1)