Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Finishing and Polishing

Finishing and Polishing

Uploaded by

PurnaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Finishing and Polishing

Finishing and Polishing

Uploaded by

PurnaCopyright:

Available Formats

Go Green, Go Online to take your course

This course has been made possible through an unrestricted educational grant. The cost of this CE course is $59.00 for 4 CE credits.

Cancellation/Refund Policy: Any participant who is not 100% satisfied with this course can request a full refund by contacting PennWell in writing.

Earn

4 CE credits

This course was

written for dentists,

dental hygienists,

and assistants.

Finishing and Polishing

Todays Composites:

Achieving Outstanding Results

A Peer-Reviewed Publication

Written by Jeff T. Blank, DMD, PA

PennWell is an ADA CERP Recognized Provider

PennWell is an ADA CERP recognized provider

ADA CERP is a service of the American Dental Association to assist dental professionals in identifying

quality providers of continuing dental education. ADA CERP does not approve or endorse individual

courses or instructors, nor does it imply acceptance of credit hours by boards of dentistry.

Concerns of complaints about a CE provider may be directed to the provider or to ADA CERP at

www.ada.org/goto/cerp.

2 www.ineedce.com

Educational Objectives

Upon completion of this course, the clinician will be able to

do the following:

1. Know the advantages of bonded composite restorations

and factors in their success.

2. Know the procedure by which composite restorations are

placed and temporary indirect restorations are fabricated.

3. Understand the importance of fnishing and polishing of

composites and methods by which this can be achieved.

4. Understand the benefts of using liquid polishers

(surface sealants).

Abstract

Recent trends in dentistry have included increases in the

number of direct composite restorations and indirect restora-

tions placed. A precise technique is required. In addition, it

is important following placement of direct composites and

temporary indirect restorations to fnish and polish these.

A number of fnishing and polishing methods is available,

including the use of liquid polishers.

Introduction/Overview

It is estimated that approximately 86 million direct composite

restorations were provided to patients in 1999, and over 50 mil-

lion crowns and bridges where teeth would require temporary

resin-based restorations (Table 1).

1

In comparison, when the

previous survey was conducted, approximately 47 million

direct composite restorations and over 37 million crowns and

bridges were placed.

As patient demand for esthetic dentistry has increased,

the use of composite resin and resin-based materials for poste-

rior restorations and indirect temporary restorations has corre-

spondingly increased, together with clinical demand for more

esthetically-acceptable and long-lasting materials for anterior

and posterior composite resin restorations.

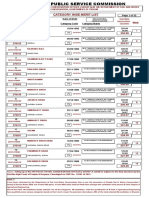

Table 1. Frequency of procedures using composite restorative materials

Type of restoration 1999 1990

Direct anterior resin 39.67 million 34.36 million

Direct posterior resin 46.12 million 13.13 million

Indirect resin temporary 50.49 million 37.56 million

Composite resin materials have been available for a little more

than four decades. Early precursors included silicate cement-

based materials these required rapid single placement, did

not permit sequential flling of the preparation and were chemi-

cally cured as well as composite resin materials that required

chairside manual mixing of two components. While resin was

an improvement over silicate cement materials, shortcomings

included the diffculty of thoroughly mixing equal amounts of

the components, the short time available for placement prior

to curing, the roughness of the cured material, and the limited

range of shades. None of the early composite materials were

clinically suitable for posterior restorations; amalgam restora-

tions were clinically superior except where esthetics was the

main determinant.

2

Composite resin restorations have evolved

rapidly, with the pace of new product development accelerating

over the last decade. Advanced composite materials and tech-

niques, new etching and bonding materials, fast curing lights,

and new fnishing and polishing materials and techniques have

all been introduced.

In 1993, composite wear was estimated to be 10% of the

wear experienced with earlier-generation composites.

3

A 1997

review of clinical papers reporting on the use of amalgam and

composite resin materials for posterior restorations with at

least fve years of data (and up to 30 years and 10 years of data

for amalgams and composites respectively) found that both

materials had similar ranges of annual failure rates.

4

Another

study found that the failure rates for primary tooth restorations

subjected to occlusal stresses were 0 15% for composite resin

restorations and 0 35.3% for amalgams.

5

One study, review-

ing the literature since 1990, showed lower annual failure rates

for posterior composite resin restorations than for amalgam

restorations (2.2% versus 3%).

6

A separate study found an an-

nual failure rate of 0 7% for amalgam and 0 9% for composite

resin restorations.

7

It should be noted, however, that for each

of these studies, rates included failure due to secondary caries,

fracture, wear and marginal defciency.

Current composite materials are light-cured; designed

to be applied either with a single insertion or by using an

incremental (layering) insertion technique; offer a wider

range of shades; and are available in macrofll, microfll and

hybrid variants. Microfll composite resins include Renamel

Microfll (Cosmedent), Heliomolar

(Ivoclar Vivadent), and

Durafll

VS (Heraeus Kulzer). Microhybrid composite res-

ins include Point 4

(Kerr), Esthet-X

(DENTSPLY Caulk),

TPH

3 (DENTSPLY Caulk), Vit-l-escence

(Ultradent) and

Tetric

(Ivoclar Vivadent).

Contemporary composite materials are esthetically pleasing

and more resistant to wear and to occlusal forces and fracture.

These materials offer the ability to use fnishing and polishing

techniques that are designed to optimize esthetics, improve

patient satisfaction and comfort, and help reduce marginal

leakage, wear and roughness.

Direct Composite Restorations

In addition to esthetics, composite resin materials offer

several other advantages over amalgam (Table 2). Bonded

composite resin restorations enable the clinician to practice

minimally-invasive dentistry. It is no longer necessary to

extend preparations or to prepare them with classical Black

cavity confgurations. Unlike with amalgam, composite

strength does not rely upon material bulk nor does compos-

ite resin rely upon undercuts for retention of the restoration

(although bonded amalgam restorations alleviated the need

for undercuts).

www.ineedce.com 3

Table 2. Advantages of composite restorations over amalgam

Esthetics

Reduced preparation size

No need to extend the width and depth of the preparation

beyond caries removal requirements

No need for undercuts

Bonding unifies material and tooth, and can reduce

marginal leakage

Composite placement can reduce underfilling of margins

Lower thermal coefficient of expansion

This has positive implications for Class II preparations in

particular, as it removes the need for an isthmus of a certain

depth or for extension of the box and preparation overall.

Due to the ability to truly bond the composite resin to the

tooth, with an appropriate technique and choice of materials

the composite resin and the tooth are unifed and retention

is achieved through bonding, minimizing preparation re-

quirements (Figure 1). With appropriate case selection and

technique, direct bonded composite resins are also effective in

providing direct durable cuspal-coverage restorations where

cusps are fractured or missing, thereby reducing the prepara-

tion required to replace fractured cusps and giving patients

an alternative treatment option to the indirect restoration

treatment option.

8

Bonding can also reduce long-term marginal leakage.

In Class II preparations, composite material placement has

been shown to result in fewer marginal gaps and underflled

margins compared to amalgam,

9

and composite also has a

lower thermal coeffcient of expansion thereby reducing

the amalgam-associated risk of cracks developing in the tooth

(Figure 2). However, composite placement is more intricate

and time-consuming and requires a more exact technique for

optimal clinical results and long-term success.

Figure 1. Modified Class II composite prep

Figure 2. Class I amalgam and associated cracks

Factors that infuence the success of composite resin direct

restorations include the preparation shape, the presence of

subgingival margins, the etching/bonding agent used, the

appropriate selection of composite resin material, the place-

ment technique, the light-cure source, and the polishing and

fnishing technique and materials.

10,11,12,13,14

Composites with

smaller-particle fller have been found to have better me-

chanical strength and wear resistance compared with those

containing larger particles.

15

Gaps within the composite bulk

have been found to be more common when using a two-layer

technique than when using a multilayer incremental insertion

technique,

16

and an incremental layering technique was found

in one study to result in less microleakage than a single-inser-

tion technique.

17

However, the use of neither single insertion

nor incremental insertion has been found to totally eliminate

microleakage at margins.

18

Careful placement, fnishing and

polishing techniques, as well as the selection of appropriate

materials, are essential for the success of bonded composite

resin restorations.

Direct Composite Placement

and Finishing Technique

Direct Composite Placement Technique

For both anterior and posterior bonded composite resin resto-

rations, the preparation is extended to remove carious tissue.

Once this has been achieved it is not necessary to remove

additional tooth structure (one exception is where staining

is present, such as old amalgam staining in a posterior, and

its removal is deemed necessary to achieve an esthetic result).

The preparation is then etched, rinsed and bonded in separate

steps, or etched and bonded in one step using a self-etching

bonding agent. Composite placement and curing follows,

with care being taken not to overfll the preparation, so as

to avoid the need for removal of grossly excessive composite

prior to fnal contouring, fnishing and subsequent polishing

of the restoration.

Class III composite restorations

Class III composite restorations were placed following sepa-

rate etching, rinsing and bonding steps (Prime and Bond

NT). To achieve an optimal esthetic result, the composite

was incrementally layered and internal white tints were placed

within the restoration, then overlaid with the main composite

shade to provide an esthetic match with adjacent teeth (Es-

thet-X

shade YE, Kerr Kolor Plus White tint).

Class II composite restoration

A Class II composite restoration was placed following re-

moval of a defective Class I restoration and interstitial caries.

In this case, etching and bonding were achieved in one step

using a self-etching bonding agent (Xeno

IV, DENTSPLY

Caulk). The composite was then incrementally layered and

cured until the preparation was flled and ready for contour-

4 www.ineedce.com

ing. As with anterior restorations, overflling during com-

posite placement should be avoided to minimize contouring

and fnishing.

Finishing Direct Composites

Available finishing kits containing discs, cups and

points include Enhance

Finishing System (DENTSPLY

Caulk), Fini (Pentron) and CompoMaster (Shofu).

Figure 3a. Preparations completed

Figure 3b. Etchant applied

Figure 3c. Application of bonding agent

Figure 3d. Final composite layer placement #7

Figure 3e. Final composites with esthetic shade and tints,

prior to polishing

Figure 4a. Defective amalgam and caries

Figure 4b. Application of self-etching bonding agent

Figure 4c. Syringe application of composite

Figure 4d. Composite placement completed

www.ineedce.com 5

These are used in a slow-speed handpiece with a dry

field and light intermittent pressure (to avoid the build-

up of heat on the tooth as well as deterioration of the fin-

ishing material). Depending on the bulk of the composite

that needs to be removed, these kits can be used alone or

after use of diamond or carbide finishing burs to improve

smoothness. Prior to polishing, the finished surface must

have its final contour and be defect-free.

The objective of finishing is to contour the composite

restoration to its final shape. This process leaves a sur-

face that is still rough and requires polishing to achieve

a smooth clinically optimal surface while enhancing

the final esthetics and comfort of the restoration for the

patient. The smoother the surface, the less opportunity

there is for biofilm development on the composite and

adjacent tooth margins. Biofilm adheres to rough sur-

faces more easily than to smooth surfaces, and composite

materials have been shown to be colonized by oral bacte-

ria, including Streptococcus mutans.

19

Careful technique

and selection of product is required for polishing, and

inappropriate usage can result in greater surface rough-

ness than existed prior to polishing. Biofilm formation

increases if composite surfaces are roughened.

20

Smooth

surfaces and margins reduce the risk of biofilm adhe-

sion and maturation, recurrent caries, gingival irritation

and staining.

Polishing Direct Composites

Polishers

Polishers are available as stand-alone products and can

also be purchased conveniently as kits containing discs,

cups and points. Polishers are fner than fnishing discs,

cups and points. Available polishers include PoGo

One

Step Diamond Micro-Polishers (DENTSPLY Caulk);

Sof-Lex

Superfne polishing discs (3M Espe), which

contains aluminum oxide; Astropol

(Ivoclar); Identofex

(Centrix) and Jiffy Polishers (Ultradent). Use of PoGo

has been found to result in less staining following immer-

sion in coffee for seven days than use of a Sof-Lex

brush,

21

and in a separate study comparing Sof-Lex

, PoGo

and

Identofex polishers on hybrid and microhybrid compos-

ites, it was found that the smoothest surface was obtained

using PoGo

and the hybrid composite.

22

Polishing pastes

An alternative polishing technique is to use a polishing

cup together with a polishing paste made specifcally for

composites such as Prisma

- Gloss (DENTSPLY

Caulk) for microflled composites or a combination of

fne and extra-fne pastes for hybrid composites (such as

use of Prisma

- Gloss followed by Prisma

- Gloss

Extrafne). Other polishing pastes available include Com-

poSite

(Shofu) and Luminescence

Plus (Premier Dental).

When using a composite polishing paste, it is important to

select the paste appropriate for the composites structure;

if there is any uncertainty, the manufacturer(s) of the paste

and composite should be consulted.

Liquid polish

Liquid polishers (surface sealants) are low-viscosity fluid

resins that provide a gloss over composite resin restora-

tions, improving final esthetics. A further objective

of liquid polishers surface sealants is to aid in

creating a marginal seal, and they have the ability to fill

microgaps. Liquid polishers reduce microleakage at com-

posite margins,

23,24,25,26

a beneficial characteristic since

poor marginal adaptation and microleakage are the most

common causes of composite restoration failure.

27

Studies

have found that use of a surface sealant following finish-

ing and polishing reduces surface roughness

28

(Figure 5)

and wear compared to control restorations receiving no

surface sealant,

29,30

and that less toothbrush wear and

maintenance of a smoother surface resulted from use of

surface sealant on large-particle composites.

31

Shinkai

et al. found 50% less wear with use of surface sealants.

32

Wear reduction through the use of surface sealants has

been found to be effective for up to two years.

33

Surface

sealants have also been shown in vitro to help prevent

stain penetration and discoloration of composite resins,

and to result in greater shade stability (Figure 6).

34,35

Their

use can positively influence surface roughness, marginal

microleakage, shade stability and wear. The procedure

takes only a few seconds of chairside time.

Figure 5a. SEM of surface after finishing

Figure 5b. SEM after polishing (liquid polish)

6 www.ineedce.com

Figure 6. In vitro stain resistance using liquid polisher

Resin-based composite prior to immersion in coffee

Resin-based composite after immersion in coffee

Resin-based composite after immersion in coffee,

with prior application of liquid polish (Lasting Touch)

Liquid polishers can be used as the fnal step in polishing

to impart a high luster, as an alternative to an ultra-fne

polishing step and to aid marginal seal. If the clinician is

accustomed to fnishing only, then liquid polish provides a

fast, one-step, patient-friendly procedure that results in a

smoother surface and high luster. This is particularly use-

ful if the patient has already undergone a lengthy proce-

dure and is eager to leave. When selecting a liquid polish,

consideration should be given to its wear resistance, stain

resistance, clarity (clear polish will not alter the appearance

of the shade of the fnished restoration), ability to fuoresce

and delivery system.

Polishing Techniques

The following cases show the procedure and final res-

toration using various combinations of finishing and

polishing techniques.

Case 1. Finishing and polishing with Enhance, PoGo

This Class IV composite resin restoration was fnished

using Enhance

followed by PoGo

. Following use of

Enhance

for fnishing and contouring, PoGo

was used to

polish, imparting a high luster (Figure 7).

Figure 7a . Restoration after finishing

Figure 7b. Polishing with PoGo

cup

Figure 7c. Polishing incisally with PoGo

disc

Figure 7d. Final restoration after finishing and polishing

www.ineedce.com 7

Case 2. Finishing and polishing

with Enhance, Lasting Touch

Teeth numbers 9 and 10 are shown with newly-placed Class

III composite resin restorations. These were fnished using

fnishing burs, followed by Enhance

.

For the polishing procedure, the composites were frst

etched, followed by paint-on application of the liquid polish.

This provided a smooth, refective surface and imparted a

high luster.

Figure 8a. Restorations following finishing

Figure 8b. Application of etchant

Figure 8c. Application of liquid polish using a rubber tip

Figure 8d. Final polished restorations

Case 3. Final finishing and polishing

with fine diamond polishing points,

followed by liquid polish

This Class II composite resin restoration was fnished using

fne diamond fnishing points, followed by liquid polish to im-

part polish and luster. As before, the restoration was etched,

rinsed and dried prior to application of the liquid polish.

Figure 9a. Finishing the restoration

Figure 9b. Polished restoration

Indirect Temporary Restorations

Indirect composite resin temporary restorations serve one

of two purposes: as a temporary restoration while a perma-

nent prosthesis (crown or bridge) is being fabricated, or as a

longer-term temporary restoration during oral rehabilitation

prior to either fabricating a fnal restoration or assessing and

determining appropriate defnitive treatment. Available

resin-based materials for temporization include PreVision

CB (Heraeus Kulzer) and Integrity

(DENTSPLY Caulk).

The temporary must have appropriate shape and contours, an

emergence profle that aids soft-tissue conditioning, smooth

margins, an acceptable shade and a smooth surface. These

will help maintain (or improve) gingival health and patient

comfort, and will reduce the ability of bioflm to adhere and

mature (Figure 10).

Polishing Indirect Temporary Restorations

Polishing temporary resin restorations provides several

benefts improved esthetics, smoothness and comfort.

Reduced staining may also be achieved (more of a factor

8 www.ineedce.com

with long-term temporary use). As with direct composite

restorations, polishing can be achieved using polishers, rub-

ber cups and pastes, and/or liquid polishing agents. While

ultra-fne polishing and use of a liquid polishing agent

would be ideal, due to its temporary nature and the length

of chairside time which the patient has already undergone,

polishing may typically be minimal or not carried out. In

these situations, use of a liquid polishing agent takes only

a few seconds and imparts a surface luster that improves

esthetics and surface smoothness.

Figure 11a. Application of liquid polish

Figure 11b. Polished temporary (Lasting Touch)

Summary

Anterior and posterior composite materials, and resin-

based materials for temporary restorations, have evolved

greatly since their introduction. Contemporary materials

offer strength, reliability and the ability to create esthetic

restorations with shading and tinting that matches adja-

cent teeth. Similarly, recent developments have provided

the clinician with several methods for finishing and pol-

ishing these restorations both of which are necessary

for optimal esthetic results and the maintenance of

oral health.

Polishing techniques available include the use of polishers,

pastes and liquid polishers. These can be used in combina-

tion. Liquid polishers enhance esthetics, impart a high luster,

create a smoother surface and help provide a marginal seal as

the fnal step in polishing. In addition, use of liquid polish as

a stand-alone polisher can be advantageous when the patient

has already undergone a lengthy procedure; in the case of

temporary restorations that might otherwise be fnished but

not polished, liquid polish provides a high luster and smooth

surface in seconds.

Figure 10a. Completed crown preps

Figure 10b. Placing resin-based material in the impression

Figure 10c. Repositioning the impression with resin in place

Figure 10d. Finishing the indirect restoration

Figure 10e. Indirect temporary cemented in place

www.ineedce.com 9

References

1. Ameri can Dental Associ ati on. The 1999 Sur vey of Dental Ser vi ces

Rendered. 2002.

2. Phillips RW. Should I be using amalgam or composite restorative materials? Int

Dent J. 1975;25(4):236241.

3. Kawai K, Leinfelder KF. Effect of surface-penetrating sealant on composite wear.

Dent Mater. 1993;9(2):108113.

4. Roulet JF. Benefits and disadvantages of tooth-coloured alternatives to amalgam.

J Dent. 1997;25(6):459473.

5. Hickel R, Kaaden C, Paschos E, Buerkle V, Garcia-Godoy F, Manhart J. Longevity

of occlusally-stressed restorations in posterior primary teeth. Am J Dent.

2005;18(3):198211.

6. Manhart J, Chen H, Hamm G, Hickel R. Buonocore Memorial Lecture. Review of

the clinical survival of direct and indirect restorations in posterior teeth of the

permanent dentition. Oper Dent. 2004;29(5):481508.

7. Hickel R, Manhart J, Garcia-Godoy F. Clinical results and new developments of

direct posterior restorations. Am J Dent. 2000;13(Spec No):41D54D.

8. Deliperi S, Bardwell DN. Clinical evaluation of direct cuspal coverage with

posterior composite resin restorations. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2006;18(5):25665;

discussion 266267.

9. Duncalf WV, Wilson NH. Marginal adaptation of amalgam and resin composite

restorations in Class II conservative preparations. Quintessence Int. 2001

May;32(5):391395.

10. Fruits TJ, Knapp JA, Khajotia SS. Microleakage in the proximal walls of direct and

indirect posterior resin slot restorations. Oper Dent. 2006;31(6):71927.

11. Owens BM, Johnson WW. Effect of insertion technique and adhesive system

on microleakage of Class V resin composite restorations. J Adhes Dent.

2005;7(4):303308.

12. Jacobsen T, Soderholm KJ, Yang M, Watson TF. Effect of composition and

complexity of dentin-bonding agents on operator variability analysis of gap

formation using confocal microscopy. Eur J Oral Sci. 2003;111:523528.

13. DAlpino PH, Svizero NR, Pereira JC, Rueggeberg FA, Carvalho RM, Pashley

DH. Influence of light-curing sources on polymerization reaction kinetics of a

restorative system. Am J Dent. 2007;20(1):4652.

14. Kawai K, Leinfelder KF. Effect of resin composite adhesion on marginal

degradation. Dent Mater J. 1995;14(2):211220.

15. Suzuki S, Leinfelder KF, Kawai K, Tsuchitani Y. Effect of particle variation on wear

rates of posterior composites. Am J Dent. 1995;8(4):173178.

16. Samet N, Kwon KR, Good P, Weber HP. Voids and interlayer gaps in Class 1

posterior composite restorations: a comparison between a microlayer and a 2-

layer technique. Quintessence Int. 2006;37(10):803809.

17. Owens BM, Johnson WW. Effect of insertion technique and adhesive system

on microleakage of Class V resin composite restorations. J Adhes Dent.

2005;7(4):303308.

18. Santini A, Plasschaert AJ, Mitchell S. Effect of composite resin placement

techniques on the microleakage of two self-etching dentin-bonding agents. Am

J Dent. 2001;14(3):132136.

19. Brambilla E, Cagetti MG, Gagliani M, Fadini L, Garcia-Godoy F, Strohmenger

L. Influence of different adhesive restorative materials on mutans streptococci

colonization. Am J Dent. 2005;18(3):173176.

20. Carlen A, Nikdel K, Wennerberg A, Holmberg K, Olsson J. Surface characteristics

and in vitro biofilm formation on glass ionomer and composite resin. Biomaterials.

2001;22(5):481487.

21. Turkun LS, Leblebicioglu EA. Stain retention and surface characteristics of posterior

composites polished by one-step systems. Am J Dent. 2006;19(6):343347.

22. St. Georges AJ, Bolla M, Fortin D, Muller-Bolla M, Thompson JY, Stamatiades PJ.

Surface finish produced on three resin composites by new polishing systems.

Oper Dent. 2005;30(5):593597.

23. Owens BM, Johnson WW. Effect of new generation surface sealants on the

marginal permeability of Class V resin composite restorations. Oper Dent.

2006;31(4):481488.

24. Ramos RP, Chimello DT, Chinelatti MA, Dibb RG, Mondelli J. Effect of three surface

sealants on marginal sealing of Class V composite resin restorations. Oper Dent.

2000;25(5):448453.

25. Ramos RP, Chinelatti MA, Chimello DT, Dibb RG. Assessing microleakage in resin

composite restorations rebonded with a surface sealant and three low-viscosity

resin systems. Quintessence Int. 2002;33(6):450456.

26. Estafan D, Dussetschleger FL, Miuo LE, Kondamani J. Class V lesions restored

with flowable composite and added surface sealing resin. Gen Dent.

2000;48(1):7880.

27. Ferdianakis K. Microleakage reduction from newer esthetic restorative materials

in permanent molars. J Clin Pediatr Dent. 1998;22(3):221229.

28. Attar N. The effect of finishing and polishing procedures on the surface roughness

of composite resin materials. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2007;8(1):2735.

29. Dickinson GL, Leinfelder KF, Mazer RB, Russell CM. Effect of surface penetrating

sealant on wear rate of posterior composite resins. J Am Dent Assoc.

1990;121(2):251255.

30. Shinkai K, Suzuki S, Leinfelder KF, Katoh Y. Effect of surface-penetrating sealant

on wear resistance of luting agents. Quintessence Int. 1994;25(11):767771.

31. dos Santos PH, Consani S, Correr Sobrinho L, Coelho Sinhoreti MA. Effect of

surface penetrating sealant on roughness of posterior composite resins. Am J

Dent. 2003;6:16(3):197201.

32. Shinkai K, Suzuki S, Leinfelder KF, Katoh Y. Effect of surface-penetrating sealant

on wear resistance of luting agents. Quintessence Int. 1994;25(11):767771.

33. Dickinson GL, Leinfelder KF. Assessing the long-term effect of a surface

penetrating sealant. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993;7:124;6872.

34. Doray PG, Eldinwany MS, Powers JM. Effect of resin surface sealers on

improvement of stain resistance for a composite provisional material. J Esthet

Restor Dent. 2003;15(4):2449; discussion 24950.

35. Dickinson GL, Leinfelder KF. Assessing the long-term effect of a surface

penetrating sealant. J Am Dent Assoc. 1993;7:124;6872.

Author Profile

Dr. Jeff T. Blank, DMD, PA

Dr. Blank maintains a full-time practice, focusing on

cosmetic and restorative dentistry. Dr. Blank has lectured

extensively at major dental meetings throughout the U.S.,

as well as overseas in Germany, Sweden and the Pacific

Rim on cosmetic materials and techniques. He is an Ad-

junct Instructor in the Department of General Dentistry,

and guest lecturer for graduate and undergraduate stud-

ies, at the Medical University of South Carolina, College

of Dental Medicine. Dr. Blank graduated from MUSC in

1989, and is an active member of the American Academy

of Cosmetic Dentistry, the Pierre Fauchard Honorary

Society, the American Dental Association, and the Acad-

emy of General Dentistry. In his leisure time, Dr. Blank

enjoys traveling, biking, camping and fly-fishing with

his family.

Disclaimer

The author of this course has no commercial ties with the

sponsors or the providers of the unrestricted educational

grant for this course.

Reader Feedback

We encourage your comments on this or any PennWell course.

For your convenience, an online feedback form is available at

www.ineedce.com.

10 www.ineedce.com

Questions

1. It is estimated that approximately

_______________ direct composite

restorations were provided to patients

in 1999.

a. twenty million

b. thiry-six million

c. seventy-fve million

d. eighty-six million

2. Early precursors of composite resins

included _______________.

a. silicate cement-based materials

b. composites with two components that were

manually mixed

c. acrylic with four components that were titrated

d. a and b

3. None of the early composite

materials was clinically suitable

for posterior restorations.

a. True

b. False

4. Advances in composite resin

materials and techniques have

included _______________ .

a. new bonding materials

b. fast curing lights

c. new fnishing and polishing materials

d. all of the above

5. Bonded composite resin

restorations ___________.

a. enable the practice of minimally-

invasive dentistry

b. remove the need for undercuts for retention

c. are inferior to bis-GMA

d. a and b

6. Direct bonded composite resins

can be effective in providing direct

durable cuspal-coverage restorations.

a. True

b. False

7. Compared to amalgam, bonded

composite Class II restorations have

been shown to _______________.

a. result in fewer marginal gaps

b. result in fewer underflled margins

c. have a lower thermal coeffcient of expansion

d. all of the above

8. Compared to amalgam,

placement of composite

restorations ___________.

a. is simpler and quicker

b. is more intricate and requires a more

exact technique

c. requires less bonding agent

d. none of the above

9. Composites with larger-particle fller

have been found to have better me-

chanical strength and wear resistance

compared with those containing

smaller-particle fller.

a. True

b. False

10. Etching and bonding can be carried

out _______________.

a. in one step

b. in two steps

c. anytime and are not necessary

d. a and b

11. Studies have found that an

incremental layering technique for

composites results in ____________.

a. less microleakage than a single-

insertion technique

b. fewer gaps in the composite bulk compared to

a two-layer insertion technique

c. total elimination of microleakage at the margins

d. a and b

12. If care is taken not to overfll

preparations while placing

composite, ____________.

a. no fnishing will be required

b. less composite will need to be removed prior to

fnishing and polishing

c. there will be space for contraction

d. b and c

13. Finishing of direct composite

restorations can be achieved

using _______________.

a. fnishing cups, discs and points

b. diamond fnishing burs

c. carbide fnishing burs

d. all of the above

14. The fnished surface of a composite

must have its fnal contour and be

defect-free prior to polishing.

a. True

b. False

15. Polishers for composites are avail-

able as ______________.

a. polishing discs, cups and points

b. polishing pastes

c. liquid polishes

d. all of the above

16. A smooth, clinically optimal

composite requires that the surface

be ______________.

a. plasticized

b. polished

c. enhanced with fuoride varnish

d. all of the above

17. Smooth surfaces and margins

reduce the risk of _______________.

a. bioflm adhesion and maturation

b. recurrent caries

c. gingival irritation

d. all of the above

18. When using a composite

polishing paste, it is important

to _______________.

a. use water as a coolant

b. use a high-speed handpiece and bur

c. select the paste appropriate for the

composites structure

d. none of the above

19. Liquid polishers are also known

as _______________.

a. surface sealants

b. cavity varnishes

c. surface degradants

d. all of the above

20. Liquid polishers _______________.

a. provide a gloss over composite resin surfaces

b. aid in creating a marginal seal

c. have the ability to fll microgaps

d. all of the above

21. Poor marginal adaptation

and microleakage are the most

common causes of composite

restoration failure.

a. True

b. False

22. Use of a surface sealant

following fnishing and

polishing _______________.

a. reduces surface roughness

b. reduces wear

c. improves esthetics

d. all of the above

23. _______________ found 50% less

wear with use of surface sealants.

a. Black et al.

b. Shinkai et al.

c. Brannstrom et al.

d. None of the above

24. Liquid polishers can only be used

after an ultra-fne polishing step.

a. True

b. False

25. Indirect temporary

restorations _________.

a. can be polished using a liquid polisher

b. may be intended for short-term use while a

crown or bridge is being fabricated

c. may be intended for use during

oral rehabilitation

d. all of the above

26. A smooth surface on a temporary

restoration _______________.

a. helps to improve patient comfort and to

maintain gingival health

b. is not important given that the restoration

is temporary

c. might weaken the temporary restoration

d. a and c

27. Composite material has been found

to be colonized in the intraoral

environment by _______________.

a. diphtheroids

b. anthrax

c. Streptococcus mutans

d. none of the above

28. Several polishing techniques

are available and can be used in

various combinations.

a. True

b. False

29. Composite resin restorative

materials have been available

for _______________.

a. a little over two decades

b. a little over four decades

c. a little over ffty years

d. more than sixty years

30. Contemporary composite materials

offer _______________.

a. strength and reliability

b. the ability to create esthetic restorations

c. quicker placement than using amalgam

d. a and b

PLEASE PHOTOCOPY ANSWER SHEET FOR ADDITIONAL PARTICIPANTS.

For IMMEDIATE results, go to www.ineedce.com

and click on the button Take Tests Online. Answer

sheets can be faxed with credit card payment to

(440) 845-3447, (216) 398-7922, or (216) 255-6619.

Payment of $59.00 is enclosed.

(Checks and credit cards are accepted.)

If paying by credit card, please complete the

following: MC Visa AmEx Discover

Acct. Number: _______________________________

Exp. Date: _____________________

Charges on your statement will show up as PennWell

www.ineedce.com 11

Mail completed answer sheet to

Academy of Dental Therapeutics and Stomatology,

A Division of PennWell Corp.

P.O. Box 116, Chesterland, OH 44026

or fax to: (440) 845-3447

ANSWER SHEET

Finishing and Polishing Todays Composites: Achieving Outstanding Results

Name: Title: Specialty:

Address: E-mail:

City: State: ZIP:

Telephone: Home ( ) Oce ( )

Requirements for successful completion of the course and to obtain dental continuing education credits: 1) Read the entire course. 2) Complete all

information above. 3) Complete answer sheets in either pen or pencil. 4) Mark only one answer for each question. 5) A score of 70% on this test will earn

you 4 CE credits. 6) Complete the Course Evaluation below. 7) Make check payable to PennWell Corp.

Educational Objectives

1. Know the advantages of bonded composite restorations and factors in their success.

2. Know the procedure by which composite restorations are placed and temporary indirect restorations are fabricated.

3. Understand the importance of nishing and polishing of composites and methods by which this can be achieved.

4. Understand the benets of using liquid polishers (surface sealants).

Course Evaluation

Please evaluate this course by responding to the following statements, using a scale of Excellent = 5 to Poor = 0.

1. Were the individual course objectives met? Objective #1: Yes No Objective #3: Yes No

Objective #2: Yes No Objective #4: Yes No

2. To what extent were the course objectives accomplished overall? 5 4 3 2 1 0

3. Please rate your personal mastery of the course objectives. 5 4 3 2 1 0

4. How would you rate the objectives and educational methods? 5 4 3 2 1 0

5. How do you rate the authors grasp of the topic? 5 4 3 2 1 0

6. Please rate the instructors eectiveness. 5 4 3 2 1 0

7. Was the overall administration of the course eective? 5 4 3 2 1 0

8. Do you feel that the references were adequate? Yes No

9. Would you participate in a similar program on a dierent topic? Yes No

10. If any of the continuing education questions were unclear or ambiguous, please list them.

___________________________________________________________________

11. Was there any subject matter you found confusing? Please describe.

___________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________

12. What additional continuing dental education topics would you like to see?

___________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________________ AGD Code 253

AUTHOR DISCLAIMER

The author of this course has no commercial ties with the sponsors or the providers of

the unrestricted educational grant for this course.

SPONSOR/PROVIDER

This course was made possible through an unrestricted educational grant. No

manufacturer or third party has had any input into the development of course content.

All content has been derived from references listed, and or the opinions of clinicians.

Please direct all questions pertaining to PennWell or the administration of this course to

Machele Galloway, 1421 S. Sheridan Rd., Tulsa, OK 74112 or macheleg@pennwell.com.

COURSE EVALUATION and PARTICIPANT FEEDBACK

We encourage participant feedback pertaining to all courses. Please be sure to complete the

survey included with the course. Please e-mail all questions to: macheleg@pennwell.com.

INSTRUCTIONS

All questions should have only one answer. Grading of this examination is done

manually. Participants will receive conrmation of passing by receipt of a verication

form. Verifcation forms will be mailed within two weeks after taking an examination.

EDUCATIONAL DISCLAIMER

The opinions of ecacy or perceived value of any products or companies mentioned

in this course and expressed herein are those of the author(s) of the course and do not

necessarily reect those of PennWell.

Completing a single continuing education course does not provide enough information

to give the participant the feeling that s/he is an expert in the feld related to the course

topic. It is a combination of many educational courses and clinical experience that

allows the participant to develop skills and expertise.

COURSE CREDITS/COST

All participants scoring at least 70%(answering 21 or more questions correctly) on the

examination will receive a verifcation form verifying 4 CE credits. The formal continuing

education program of this sponsor is accepted by the AGD for Fellowship/Mastership

credit. Please contact PennWell for current term of acceptance. Participants are urged to

contact their state dental boards for continuing education requirements. PennWell is a

California Provider. The California Provider number is 3274. The cost for courses ranges

from $49.00 to $110.00.

Many PennWell self-study courses have been approved by the Dental Assisting National

Board, Inc. (DANB) and can be used by dental assistants who are DANB Certifed to meet

DANBs annual continuing education requirements. To fnd out if this course or any other

PennWell course has been approved by DANB, please contact DANBs Recertifcation

Department at 1-800-FOR-DANB, ext. 445.

RECORD KEEPING

PennWell maintainsrecordsof your successful completion of any exam. Pleasecontact our

ofces for a copy of your continuing education credits report. This report, which will list

all credits earned to date, will be generated and mailed to you within fve business days

of receipt.

CANCELLATION/REFUND POLICY

Any participant who is not 100%satised with this course can request a full refund by

contacting PennWell in writing.

2008 by the Academy of Dental Therapeutics and Stomatology, a division

of PennWell

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Construction Method of High Rise BuildingDocument75 pagesConstruction Method of High Rise BuildingNishima Goyal100% (1)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Lab Report # 2Document6 pagesLab Report # 2zainyousafzai100% (1)

- Tae Evo 015 - 351 EnglDocument39 pagesTae Evo 015 - 351 EnglMantenimientoValdezGutierrezNo ratings yet

- Chiropractic: Name of Client Room Category Coverage ClientDocument6 pagesChiropractic: Name of Client Room Category Coverage ClientCh Raheel BhattiNo ratings yet

- Revision From DRDocument11 pagesRevision From DRMahmoud GamalNo ratings yet

- Rohith R Fouress Report 1Document22 pagesRohith R Fouress Report 1Nithish ChandrashekarNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Entrepreneurship Successfully Launching New Ventures Ma 4th Edition Bruce Test Bank PDFDocument36 pagesDwnload Full Entrepreneurship Successfully Launching New Ventures Ma 4th Edition Bruce Test Bank PDFferiacassant100% (14)

- Ranger Archetypes: DervishDocument1 pageRanger Archetypes: DervishI love you Evans PeterNo ratings yet

- P1-F Revision For Midyear - Listening - The Sydney Opera HouseDocument4 pagesP1-F Revision For Midyear - Listening - The Sydney Opera HouseYusuf Can SözerNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Consumption in The Fast Fashion IndustryDocument9 pagesAn Analysis of Consumption in The Fast Fashion IndustryFulbright L.No ratings yet

- Datacard Maxsys Card Issuance System: Embossing/Indent Module Service ManualDocument172 pagesDatacard Maxsys Card Issuance System: Embossing/Indent Module Service ManualNguyễn Hữu ThịnhNo ratings yet

- Analysis and Modelling of CFT Members Moment Curvature AnalysisDocument10 pagesAnalysis and Modelling of CFT Members Moment Curvature AnalysisMahdi ValaeeNo ratings yet

- Biochemistry: DR - Radhwan M. Asal Bsc. Pharmacy MSC, PHD Clinical BiochemistryDocument13 pagesBiochemistry: DR - Radhwan M. Asal Bsc. Pharmacy MSC, PHD Clinical BiochemistryAnas SeghayerNo ratings yet

- Yield of Cucumber Varieties To Be ContinuedDocument24 pagesYield of Cucumber Varieties To Be ContinuedMaideluz V. SandagNo ratings yet

- PIX MR CatalogueDocument60 pagesPIX MR CatalogueAmir SofyanNo ratings yet

- Chap016.ppt Materials Requirements PlanningDocument25 pagesChap016.ppt Materials Requirements PlanningSaad Khadur EilyesNo ratings yet

- Design of Storm Sewer MeterDocument2 pagesDesign of Storm Sewer MeterrachanaNo ratings yet

- ConsolidatedDocument46 pagesConsolidatedJ. Karthick Myilvahanan CSBSNo ratings yet

- LCI 80 Standard Line Control DisplayDocument2 pagesLCI 80 Standard Line Control DisplayMeasurementTechNo ratings yet

- Kruss Bro k20 enDocument2 pagesKruss Bro k20 enBilal KhanNo ratings yet

- CRICKET SKILLS INJURY (PPT For Assignment) LnipeDocument59 pagesCRICKET SKILLS INJURY (PPT For Assignment) LnipeVinod Baitha (Vinod Sir)No ratings yet

- Power TransformersDocument4 pagesPower TransformerssabrahimaNo ratings yet

- Performance Claims by Brian WilliamsonDocument20 pagesPerformance Claims by Brian Williamsonc rkNo ratings yet

- UsermanualDocument23 pagesUsermanualJagdish SinghNo ratings yet

- ABS Schema ElectricaDocument5 pagesABS Schema ElectricadickenszzNo ratings yet

- Spark Plug Testing MachineDocument27 pagesSpark Plug Testing MachineJeetDangiNo ratings yet

- Embedded SystemDocument75 pagesEmbedded SystemDnyaneshwar KarhaleNo ratings yet

- Systemic Pathology QuestionDocument4 pagesSystemic Pathology QuestionAnderson Amaro100% (1)

- EFX By-Pass Level Transmitter - NewDocument32 pagesEFX By-Pass Level Transmitter - Newsaka dewaNo ratings yet

- Sat Practice Test 1 20 34Document15 pagesSat Practice Test 1 20 34Kumer ShinfaNo ratings yet