Professional Documents

Culture Documents

500241

500241

Uploaded by

andreadoumaria5Original Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

500241

500241

Uploaded by

andreadoumaria5Copyright:

Available Formats

A Preliminary Report on Some Unpublished Mosaics in Hagia Sophia: Season of 1950 of the

Byzantine Institute

Author(s): Paul A. Underwood

Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 55, No. 4 (Oct., 1951), pp. 367-370

Published by: Archaeological Institute of America

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/500241 .

Accessed: 24/04/2014 13:35

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

Archaeological Institute of America is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

American Journal of Archaeology.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 83.212.10.20 on Thu, 24 Apr 2014 13:35:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

American Journal

of Archaeology

Vol. 55, No. 4 (October, 1951)

A PRELIMINARY REPORT ON SOME UNPUBLISHED MOSAICS IN HAGIA

SOPHIA: SEASON OF 1950 OF THE BYZANTINE INSTITUTE

BY

PAUL A. UNDERWOOD

Field

Director,

The

Byzantine Institute,

Inc.

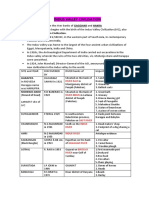

PLATE 17

Despite

the severe losses suffered

during

the

spring

and summer of

1950,

first with the death of its Presi-

dent,

Robert P.

Blake,

Professor of

Byzantine History

at Harvard

University,

and a little later of Professor

Thomas

Whittemore,

its

founder, Director,

and mov-

ing spirit

for so

many years,

the

Byzantine

Institute

was nevertheless able to

carry

forward its work in

Istanbul. From late

July

to

early

November work

was conducted in three former churches now estab-

lished as museums under the

charge

of the

Ministry

of Public Instruction of the Turkish

Republic.

In this

campaign

the same

facilities, encouragement,

and

courtesies that had been afforded Professor Whitte-

more were

graciously

extended

by

the Turkish

govern-

ment to the author of this

report.

While

continuing

the rehabilitation of the extensive

mosaic

cycles

at the Kahrieh

Djami (formerly

the

monastic church of St. Saviour in the

Chora)

which

was

begun

in

1948,

new work was undertaken at the

Church of the Theotokos Pammakaristos

(Fetiyeh

Djami).

The

subject

of this

report

concerns the third

project

of the season: the

investigation, preservation,

and

cleaning

of some mosaic

fragments

in a

large

vaulted

chamber which

lies,

as a second

story, immediately

above the entrance vestibule of the

great

church of

Hagia Sophia (pl. 17).

The

room,

whose floor is

ap-

proximately

at

gallery level,

can be entered at

present

only through

the

great doorway

at the southern end

of the axis of the West

Gallery.

Above the

door,

inside the

room,

the semi-circular

tympanum

contains

fragments

of two of its

original

three

figures

in mosaic. Elsewhere in the

room,

at

scattered

points

in the

vaults,

are

fragments

of four-

teen other

figures, many

of them the merest bits and

pieces,

and all

adhering

to the

masonry

in a most

pre-

carious manner. These mosaics have never been

covered with

plaster

or obscured

by

white-wash.

They

seem, however,

to have been mentioned

only

twice in

published

works. The first is an allusion

by Salzenberg

to the mosaics above the

door,

without

any

identifica-

tion of the

figures,

and a statement

by

the same author

that the vaults were ornamented with mosaic

figures,

one of which he illustrated in a

drawing, again without

identification.' The second is contained in a document

published

in 1902

by

G. P.

Beglery

Is

in which a

visitor to the

galleries

in 1847 claims to have seen a

Deesis and full

length figures

of the Twelve

Apostles.

Today,

of the

fragments

of sixteen

figures

it is

possible

to

identify twelve, mostly by

means of

deciphering

inscriptions

in the

plaster setting-bed.

The forms of the vaults and the

irregular shape

of

the room are

presented

in the

preliminary

measured

drawing reproduced

in the

accompanying plate (pl.

17).2

Since the main

purpose

of the

drawing

is to

present

the mosaics in their true forms and dimensions

and show their

positions

in the

room, the

longitudinal

sections are drawn as

though

the rounded vaults were

flat vertical

planes

that continue the vertical

planes

of the walls.3

Longitudinally

the room is divided into

three

bays separated

from one another

by

arches. The

first

bay,

which contains no

surviving mosaics, was

originally

a

simple

barrel-vault. Its eastern half seems

subsequently

to have been rendered somewhat

irregu-

lar

by

later

repairs.

The second and third

bays,

while

giving

the effect of

barrel-vaults,

are

slightly

domed

along

the

ridge,

their bricks are laid in the manner of

groin-vaults

with the

groins

flattened

out,

and the walls

below them

penetrate vertically beyond

the

spring

lines to form a lunette in each side of each

bay,

thus

providing

a total of four lunette

penetrations.

These

two southern

bays

form a unit and

together

stand in

contrast to the first. It will be seen that in their

iconographic program

the two southern

bays

were

treated as a continuum and must have formed a unit

within the

program

of the whole.

Adhering

to the

masonry

are five

patches

of

plaster,

each

containing

smaller areas of mosaic tesserae. The

first,

in the

tympanum

at the northern end

("A"

in

plan

and

sections),

contains two

figures.

The second

(at "B") presents

bits of four

figures:

the

tip

of a head

which once came at the center of the arch

separating

the first two

bays,

the shoulders of two busts in the

lunette of the second

bay,

and the foot and lower

gar-

ments of a

figure

in a second zone above the traces

of an ornamental band. The third

patch (at "C")

is

367

This content downloaded from 83.212.10.20 on Thu, 24 Apr 2014 13:35:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

368 AMERICAN

JOURNAL

OF ARCHAEOLOGY

[AJA

55

confined to the lunette in the East wall of the third

or southern

bay

and contains

fragments

of three

busts,

two of them

relatively

well

preserved.

The fourth

patch (at "D")

is in the western lunette of the same

bay, opposite "C",

and has

very

small

fragments

from the heads of the three busts that once filled the

lunette. The fifth

patch

is overhead between these

last two.

Although

the

drawing

shows it in two

parts,

it is in

reality

one area of

plaster

which retains

parts

of four

figures

in

mosaic,

two in each of the two

upper

zones which met at the summit of the vault in an

ornamental band that must have run the

length

of

the two southern

bays,

if not of the whole room.

In the first area of

plaster

and mosaic

("A"),

as in

all others

throughout

the

room,

the actual mosaic

tesserae survive

only

in the

figures;

almost without

exception

the

gold

cubes of the

background

have dis-

appeared.

It is evident that at some time the mosaics

of this room were looted of all

gold cubes, perhaps

because of a need for them in

repairs

to the

gold

grounds

of the vaults elsewhere in the

building.

As in

Kilisse

Djami

in

Istanbul,

the cubes of the

background

seem to have been

scraped

off the

setting-bed

with

some

care,

for

apparently

the

attempt

was made to

spare

the

figures.

The

figures

themselves

have,

of

course,

suffered mutilation and deterioration around

the

edges

where little

by

little the cubes have

dropped

away.

The fact that so much remains of the

setting-bed,

that

is,

the

layer

of

plaster

into which the tesserae

were

inserted,

has made it

possible

to reconstruct some

lost details and to

decipher many

of the

inscriptions.

This is because of the fact that the

setting-bed,

as

usual,

was

painted,

before the cubes were

inserted,

as

though

the work were to be a fresco

painting.

All

inscriptions

were

painted

in black to serve as

guidance

to the mosaicist. Where the cubes have fallen out or

been removed the

underpainting supplies

much infor-

mation.

The lunette above the

door,

which is in

process

of

consolidation and not

yet

cleaned of its scum of dirt

and

oily

carbon

deposits

from

smoke,

now consists of

two

figures.

The central

figure

of

Christ,

of monu-

mental

proportions (note,

for

example,

the massive-

ness of the wrist and hand raised in

blessing),

is

shown seated

upon

a throne. To His

right

stands the

Mother of

God,

arms extended in

supplication,

while

the

figure

that once stood to His left is

completely

gone, only

a bit of the nimbus

having

survived in the

setting-bed.

The natural

assumption

would be that

the

composition

was a Deesis of which

only

the

Prodromos is

missing.

The correctness of this

assump-

tion would

depend

somewhat

upon

the date of the

mosaic,

and it is

impossible

to advance serious con-

siderations for its

dating,

on

stylistic grounds,

until

the

necessary repairs

and

cleaning

have been com-

pleted.

In so far as it is

possible

at

present

to

judge

the

style

it is not

incompatible

with that of the late

ninth

century,

a

dating suggested by

the content of

other

parts

of the

iconographic program

of which this

mosaic could well have been a

part.

If this is

true,

it cannot be taken for

granted

that the lunette con-

tained a true Deesis.

From a

study

of the

setting-bed

on either side of

the

figure

of Christ it is clear that the throne was of

the

type

with a

lyre-back

similar to the one in the

lunette above the

imperial

doors of the narthex of

Hagia Sophia,*

a mosaic which

seems,

if we omit the

kneeling Emperor,

to have been of a

type

antecedent

to the Deesis in that it

represents

the Mother of God

and an

archangel

on either side of Christ in the

medallions.

The second

patch

of

plaster (at

"B" in the

drawing)

retains

only

small areas in mosaic tesserae of two of

the

original

three busts in the lunette and of the

lower extremities of what was once a full

length figure

in an

upper zone,

while

only

the

very top

of the head

and

part

of the

nimbus,

a crossed

staff,

and the

incomplete inscription

1T

T

...,

are

preserved

in the

setting-bed,

devoid of all

cubes,

to the left of the

lunette. The first of a series of busts in the two south-

ernmost

bays was, therefore,

TT-CT[PO

C].

He car-

ried a crossed staff over his left shoulder and was

placed

at the base of the arch between the first and second

bays.

The bust next to

him,

enframed with his two

companions

within a border that once curved

up

over

the lunette and

merged

with the horizontal band

separating

the two

zones,

now has inscribed in the

setting-bed

to the left

only

the last three letters of

6

,-ytos.

But the

figure

can be identified because it

too carried a crossed staff. This must have been a

portrait

of the

Apostle Andrew,

elder brother of Peter

and traditional founder of the See of

Constantinople,

because

Byzantine iconography

conferred the crossed

staff

only

to Peter and Andrew

among

the twelve

and,

as will be made

evident,

all twelve

Apostles

were once

ranged,

six on either

side,

in the lower zones

of the room. The third

figure just

to the

right

of

Andrew and once the central one of three in the

lunette,

cannot be identified

by

name but must

surely

represent

another of the

Apostles. Only

the left

shoulder and the

tip

of the beard are

preserved.

Above the horizontal band of ornament that con-

nected the

tops

of the lunettes is an area of mosaic

tesserae within a

larger

area of

setting-bed.

In mosaic

a foot and the hem of a

garment

are

easily recognized.

Only by

the closest observation of the

setting-bed

and in

strong light

does one become aware of the fact

that this

figure

carried an

open, inscribed,

scroll. The

left-hand

part

of the scroll

remains,

in the

setting-bed,

and this not to its full

length.

But the

piece

of scroll

thus

preserved

contains

forty-two

characters which

This content downloaded from 83.212.10.20 on Thu, 24 Apr 2014 13:35:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

1951]

THE BYZANTINE INSTITUTE 369

make

possible

the identification of the text of the

entire scroll as Ezekiel

I, parts

of verses 4 and 5:

"And I

looked, and, behold,

a whirl-wind came out of

the north . . . and a

brightness

was about it . . . the

likeness of four

living

creatures." This is all that can

be said at

present

about this

figure-whether

or not

it identifies it as the

prophet

Ezekiel.

The third

patch

of

plaster

and mosaic is confined

to the lunette on the eastern side of the third

bay

(at "C"). Assuming

that a series of six

Apostles

oc-

curred in the lower zone of this wall the first would

have been Peter and the second Andrew. The third

and fourth would have been Andrew's

companions

in

the first lunette and the fifth would have been in the

spandrel

between the two lunettes. The

sixth,

and

last,

should therefore be the massive bust that

occupies

first

position

on the left in this second lunette. The

inscription

in the

setting-bed

on either side of this

bust

proves

this

arrangement

to be correct.

Along

the

curvature to the left of the

figure

one is able to

decipher,

first an

alpha

within an

omicron,

which is

the

monogram

for 6

li5yos,

and beneath this the name

Cl MO)N.

The vertical column to the

right

of the bust

reads:

OZHAO)TH

C. The

figure, therefore, repre-

sents the

Apostle

Simon Zelotes.

Next to Simon is a

figure

of which little remains-

On the left it is inscribed OA

IOC,

and on the

right,

F

CPMANOC,

without doubt the famous

patriarch

Germanos of

Constantinople

of the first half

of the

eighth century (715-729).

Next to him is an-

other

bishop (both

Germanos and he wear the omo-

phorion

with crosses at the

shoulders)

whose inscribed

name is

missing

but whose

portrait

is otherwise rela-

tively

well

preserved.

He will be identified later.

The remnants of mosaic in the lunette

directly

opposite (at "D")

are even more

fragmentary

than

the

others, yet,

all three busts can be identified. The

figure

to the

right

is the

pendant

to Simon Zelotes

across the

way,

and thus

might

be

expected

to be the

last of the series of six

Apostles

in the western wall.

Although only

the

top

of the head is

preserved,

a

bit of the inscribed

setting-bed

shows

that,

as in the

case of

Simon,

the

6

oiytos

is rendered

by

a

monogram

to the left in order to

present

the name on that side

and the

surname, by way

of further

identification,

on the

right.

The first two letters of the name are

iota and

alpha,

and should therefore refer to one or

the other of the two

James'-either

to'

ILKow3os

6

ro00

ZEg3daLov

or to

'IaKf3os 6

roi

'AX~alov.

The first two letters of the name of the central

figure

are

again preserved

in the

setting-bed. Since,

as will be

seen,

his

companion

on the left

was,

like Germanos

across the

way,

a

patriarch

of

Constantinople,

the

fact that the name of this central

figure begins

tau

alpha

leads one to the conviction that here too was

represented

a celebrated

patriarch

of

Constantinople,

namely,

Tarasius

(784-806).

From the name of the third

figure,

at the

left,

there

remain four

complete

letters and the

top

of the fifth.

There is no doubt that he is

Methodius,

the mid-ninth

century patriarch

of

Constantinople (843-847).

Among

the four

patriarchs

shown

confronting

one

another in the two lunettes there is a discernible

chronology

and theme.

Priority among

the four is

held

by

the first

patriarch

in the eastern lunette:

Germanos

(first

half of the

eighth century).

His

pendant

in the western lunette is Tarasius

(end

of the

eighth, early

ninth

century).

Next should come the

bishop

in the eastern wall whose name is

missing,

and

finally

Methodius

(mid

ninth

century)

in the west.

If we

supply

the name

"Nicephorus"

for the un-

identified

bishop

we would

again

have another

patri-

arch of

Constantinople.5

He would also fit chrono-

logically

into the series for he succeeded Tarasius in

806 and was

patriarch

well before Methodius. The

theme, as well as the

chronology,

become evident

when certain historical events are recalled.

Germanos was the

patriarch

who was forced out of

office because he

opposed

the iconoclastic

policies

of

the

Emperor

Leo III and was later anathematized

by

the iconoclastic Council of 754. It was he who

witnessed the

banning

of

images

at the

beginning

of

the first

phase

of Iconoclasm

despite

his

opposition.

Tarasius, opposite him,

saw the end of the first

phase

and

temporarily

restored the

images, having presided

over the Seventh Oecumenical Council in 786-7 for

that

purpose.

In

identifying

the third of the

patriarchs

as

Nicephorus

we have

something

of a

repetition

of

the

experiences

of

Germanos, for,

as

patriarch during

the

reign

of Leo

V,

the

Armenian,

he

opposed

the

renewal of iconoclastic

policies and,

like

Germanos,

was

deposed.

Thus

Nicephorus was,

so to

speak,

the

second Germanos and saw the

beginning

of the second

phase

of Iconoclasm.

Finally, Methodius, pendant

to

Nicephorus

and

companion

of

Tarasius, presided

at

the final and

triumphant

restoration of

images during

the

reign

of the

Empress

Theodora. Methodius was

patriarch

at the

meeting

of the

Synod

of 843 which is

believed to have confirmed the acts of the second

council of Nicaea of 787 with

regard

to

icons.6

It was

the same

Synod

of

843, while Methodius was

patriarch,

that instituted the Feast of

Orthodoxy,

first cele-

brated on the 11th of March of that

year.

On that

occasion a

procession, originating

at the Church of the

Virgin Mary

at

Blachernae,

went to the Great Church

of

Hagia Sophia where,

after careful

exposition

of the

theological

basis for the veneration of sacred

images,

the

triumph

over the

heresy

of Iconoclasm was cele-

brated. In the

Synodicon

of the Feast of

Orthodoxy7

the

following

four

patriarchs

are

singled out,

as a

group,

and

especially

acclaimed as true

priests

of

God,

This content downloaded from 83.212.10.20 on Thu, 24 Apr 2014 13:35:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

370 AMERICAN

JOURNAL

OF ARCHAEOLOGY

defenders and teachers of

Orthodoxy: Germanos,

Tarasius, Nicephorus,

and

Methodius,

in that order.

To them all

present

bow down.

They

were thus bound

together

as an

epitome

of the

fight against Iconoclasm,

and a

recognition

of their

unity

in that

fight

is

made,

even to this

day,

not

only

in their

being jointly

ac-

claimed in the service of the

Feast,

but in these mosaics

in

Hagia Sophia

as

well,

where

they

are honored in a

remarkable

way by being ranged

with the

Apostles

of Christ as the true didaskaloi of

Orthodoxy.

The fifth area of mosaic and

setting-bed hangs

most

precariously

overhead. It contains

fragments

of four

full

length figures

which

originally

stood in the two

upper

zones. The orant

figure

in the eastern

upper

zone is

preserved

in

part

to most of its full

length.

The saint is

young

and

beardless,

and at a

glance

might

be

thought

to be

female, but,

as can most

easily

be seen even in moderate

light

from the floor or

in a

photograph,

the

inscription

identifies the

figure

as

Saint

Stephen (CT

C4ANO0

C).

We have here,

therefore,

the first Christian

martyr.

The

very

charac-

teristics of dress and feature shown in the mosaic can be

paralleled

in other

representations

of the

Protomartyr.

The head to the

right,

all that remains of the first

figure

at the South end of the

room,

is

clearly

that of

an

imperial personage.

The lower fillet of his crown,

studded with

representations

of

pearls,

is still

pre-

served in mosaic and from the crown are

suspended

the

imperial prependulia. Enough

of the costume sur-

vives on the

right

shoulder to show that the

figure

was clad in a

gold-embroidered

loros.

Exactly

as

in all other

figures

this one is inscribed at the left

OA FlO C. The name of the

saint,

on the

right,

is

not

complete,

but the letters CON CTAN are

easily

deciphered

in the

setting-bed. Judging

from the

align-

ment of this

fragment

of the

inscription

with that

accompanying

Saint

Stephen,

there would have been

space

above the 0) for

only

one letter. If we

supply

a

K as the

missing

first letter the name should without

doubt be

completed

as

[K]ION

CTAN

[TINO

0C].

Beside the first Christian

martyr

there

stood,

there-

fore,

the first Christian

Emperor.

Of the

figure

that once stood

opposed

to Constantine

("D"

on the

drawing), only

the left hand remains. It

was an orant

figure

with

long

sleeves and

tightly fitting

cuffs.8

Opposite

Saint

Stephen

was a

bishop;

two

arms of the cross on the

omophorion

of the

right

shoulder remain.

With some effort of the

imagination

it is

possible

to

gain

an

impression

of the once

splendid

decoration of

a

good part

of this room. Below the busts there was

doubtless a

plaster cornice,

and below

that,

all the

way

to the

floor,

there were

certainly

'marble revet-

ments. Some of the metal attachments are still visible

in the

walls,

and

Salzenberg speaks

as

though

the

marbles were still in

position

a

century

ago.9

The

floor was

paved

in

patterns

formed of marble slabs.

Their

imprint

is still visible. In the lower zones of the

vaults of the two southernmost

bays

there were

origi-

nally

twelve

Apostles

and four Patriarchs

(sixteen

busts in this

part

of the

room).

From the

spacing

of

the

fragmentary

survivors of the

upper

zones and

observation of their relation to the busts in the lunettes

beneath,

it is certain that

originally twenty

full

length

figures occupied

the two

upper

zones. This

gives us,

for the two

bays,

a total of

thirty-six figures

and

busts. When the three

figures

above the door at the

northern end and an unknown number of

figures

in

the barrel vault

immediately

in front of them are

added,

it is evident that the room exhibited a

truly

impressive array

of mosaic

figures-aside

from the

mosaics in the

great

naos of the

Church,

the

largest

and most

compact group

of which we have

any

evi-

dence in

Hagia Sophia.

x

W.

Salzenberg,

Alt-christliche Baudenkmale von Con-

stantinopel (Berlin 1854) 18, 32,

and

pl. 31, fig.

7.

'

G. P.

Beglery,

in

IzvgstiyaRusskagoArchaeologi'eskago

Instituta v

Konstantinopolg (Sofia) VIII,

1-2

(1902),

117-

118. Certain statements and inferences make it uncertain

that this document

really

refers to the mosaics here under

discussion.

2

The forms of the vaults are in

reality quite

different

from those

suggested

in

any previously published plan

of

Hagia Sophia. Compare,

for

example,

the

plan

of Salzen-

berg, op.

cit.

(supra

n.

1), pl. 7;

E. M.

Antoniades,

"EK4paats

ri~

'A-yla

s lolas

(Athens)

I

(1907), pl.

IH'

and

II

(1908) 293, fig. 367;

E. H.

Swift, Hagia Sophia

(New

York

1940) pl. 2,

all of which

falsely

indicate the

presence

of three

groin

or cross-vaults.

3

The true

heights

of the vaults above the floor can be

approximated by lowering

the section lines of the summit

of the vault so as to rest on the

top

of the two

tympana

at

either end.

4

T.

Whittemore,

The Mosaics

of

St.

Sophia

at

Istanbul,

Preliminary Report

of the First Year's

Work,

1931-1932

(Oxford 1933) pl.

12.-

r

There are

many representations

of

Nicephorus

in

art,

some from the ninth

century.

The

type

is

perfectly

compatible

with our identification of his

portrait.

6

The records of this

Synod

are lost.

SAs found in the Triodion of the Greek Orthodox

Church,

ed. M. I. Saliberos

(Athens,

n.

d.) 146,

2.

8

One is

tempted

to

speculate

that a suitable

pendant

to Constantine would be his sainted mother Helena.

SOp.

cit.

(supra

n.

1)

18.

This content downloaded from 83.212.10.20 on Thu, 24 Apr 2014 13:35:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

.._MO3A..

O. ---UI-

HAGIA SOPHIA, ISTANBUL. MOSAIC FRAGMENTS IN Roo

Am. . ..

.--

-.

;-:.-...- ::4.-..A

This content downloaded from 83.212.10.20 on Thu, 24 Apr 2014 13:35:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and ConditionsPLATE 17

~?i

C

$URFACE

SREND

QNR1

,('7":r

IN ROOM ABOVE SOUTHWEST VESTIBULE

P

AU.

This content downloaded from 83.212.10.20 on Thu, 24 Apr 2014 13:35:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5823)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (852)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (541)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (823)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (403)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Ancient Civilization HousingDocument14 pagesAncient Civilization HousingPulkit TalujaNo ratings yet

- Indus Valley Civilisation: HarappaDocument14 pagesIndus Valley Civilisation: HarappaSatyaReddyNo ratings yet

- Q1 DLL Mapeh - 5 Week 3Document8 pagesQ1 DLL Mapeh - 5 Week 3MELODY GRACE CASALLANo ratings yet

- EVANS, C. y B. MEGGERS. 1968. Archeological Investigations On The Rio Napo, Eastern EcuadorDocument262 pagesEVANS, C. y B. MEGGERS. 1968. Archeological Investigations On The Rio Napo, Eastern EcuadorRCEBNo ratings yet

- NCERT Fine Arts Class 11Document9 pagesNCERT Fine Arts Class 11anju agarwalNo ratings yet

- Egyptian MummiesDocument12 pagesEgyptian MummiesadriskellwcsNo ratings yet

- Petrie, Syria and Egypt From The Tell Amarna LettersDocument197 pagesPetrie, Syria and Egypt From The Tell Amarna Letterswetrain123No ratings yet

- Stephen McKenna 2011Document112 pagesStephen McKenna 2011Alek PhabiovskyNo ratings yet

- Flint KnappingDocument8 pagesFlint KnappingSandra100% (2)

- Contextualizing Material Culture in South and Central Asia in Pre-Modern TimesDocument22 pagesContextualizing Material Culture in South and Central Asia in Pre-Modern TimesReiki YamyaNo ratings yet

- The New 7 Wonders of The WorldDocument5 pagesThe New 7 Wonders of The WorldandresNo ratings yet

- Basket Hulled Boats of Ancient ChampaDocument9 pagesBasket Hulled Boats of Ancient ChampaNguyen Ai DoNo ratings yet

- Egyptian Moulding Columns and CapitalsDocument8 pagesEgyptian Moulding Columns and CapitalsPaula Hewlett PamittanNo ratings yet

- 11KV LDDocument18 pages11KV LDSachin JainNo ratings yet

- Amphitheatres of Roman BritainDocument254 pagesAmphitheatres of Roman BritainEva DimitrovaNo ratings yet

- Multivariate Statistical Approaches in Archeology: A Systematic ReviewDocument7 pagesMultivariate Statistical Approaches in Archeology: A Systematic ReviewyamiyxopNo ratings yet

- Rice 1999 On The Origins of PotteryDocument54 pagesRice 1999 On The Origins of PotteryAgustina LongoNo ratings yet

- Maya FloodDocument10 pagesMaya Floodrevolucionreverdecer100% (1)

- Research PaperDocument2 pagesResearch Paperapi-208339428No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument852 pagesUntitledJuly QiNo ratings yet

- StonehengeDocument2 pagesStonehengeУльяна ЧеботарёваNo ratings yet

- BATL092Document9 pagesBATL092Roxana TroacaNo ratings yet

- Clay Singshots From The Roman Fort Nove at ČezavaDocument8 pagesClay Singshots From The Roman Fort Nove at ČezavanedaoooNo ratings yet

- Bcra 16-3-1989Document64 pagesBcra 16-3-1989Cae MartinsNo ratings yet

- Nick Szabo: Shelling Out: The Origins of MoneyDocument24 pagesNick Szabo: Shelling Out: The Origins of MoneyNelson Danny JuniorNo ratings yet

- Activity 2 RiphDocument2 pagesActivity 2 RiphglyselleannerasalanNo ratings yet

- HSC Ancient History Pompeii and HerculaneumDocument10 pagesHSC Ancient History Pompeii and HerculaneummentoschewydrageesNo ratings yet

- Zindan Magarasi (Gephyra)Document11 pagesZindan Magarasi (Gephyra)Burak TakmerNo ratings yet

- Dragoman Oanta Archaeology in RomaniaDocument42 pagesDragoman Oanta Archaeology in RomaniaDragos BecheruNo ratings yet