Professional Documents

Culture Documents

How Does Today's US Crisis Compare With The 1990s Japanese Crisis?

How Does Today's US Crisis Compare With The 1990s Japanese Crisis?

Uploaded by

nguyenmanhtien88Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

How Does Today's US Crisis Compare With The 1990s Japanese Crisis?

How Does Today's US Crisis Compare With The 1990s Japanese Crisis?

Uploaded by

nguyenmanhtien88Copyright:

Available Formats

No.

62

J uly 2009

This study was

prepared under the

authority of the

Treasury and

Economic Policy

General Directorate

and does not

necessarily reflect the

position of the M inistry

for the Economy,

I ndustry and

Employment.

How does today's US crisis compare with

the 1990s J apanese crisis?

Both the Amer ican and the Japanese cr ises or iginated in the bur sting of specula-

tive bubbles, for cing pr ivate agents households in the case of the USA, and non-

banks in the Japanese case to r educe their debt. In the case of Japan, debt

r eduction in the midst of a financial cr isis tr igger ed a deflationar y spir al. A Japa-

nese-style deflationar y spir al seems unlikely in the United States, despite simila-

r ities r egar ding the depth of the financial cr isis and the scale of the excesses

needing to be unwound.

Japan enter ed a deflationar y spir al in the wake of a pr otr acted depr ession as a

r esult of a ser ies of specific factor s, some inter nal ( such as the length of time

taken to br ing hidden doubtful assets out into the open) , and some exter nal ( e.g.

the Asian cr isis and the appr eciation of the yen) , at a time when the economy was

alr eady extr emely fr agile.

A highly aggr essive economic policy r esponse could enable the United States to

aver t a deflationar y spir al. The Amer ican author ities ar e concentr ating on avoi-

ding r epeating the mistakes of their Japanese counter par ts. Their management

of the cr isis appear s to have been mor e r esponsive ex ante, and mor e ambitious

in scope, with a ser ies of r apid, tar geted and lar ge-scale stimulus plans, aggr es-

sive r ate-cutting, unconventional monetar y policy measur es, and the cr eation of

a defeasance str uctur e to buy-up "toxic assets".

The dr op in consumer pr ices on a

year -on-year basis obser ved in the

United States since Mar ch 2009 is

mainly attr ibutable to a base effect on

ener gy pr ices. This is likely to be tem-

por ar y only.

Source: DGTPE

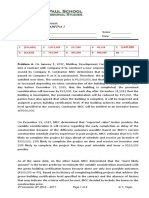

Monetary policy responses after the bursting of the US and J apanese

property bubbles

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

- 2 yrs property

bubble bursts

2 yrs 4 yrs 6 yrs 8 yrs 10 yrs

Japanese key rate Fed key rate

%

Fed implements

unconventional

monetary policy

BoJ implements

quantitative easing

TRSOR-ECONOMICS No. 62 J uly 2009 p. 2

1. The origins of the American crisis resemble those of the J apanese crisis in the 1990s

1.1 J apan's deflationary crisis arose fromnon-

banks' need to reduce their debt

Pr ior to the Japanese cr isis ther e was an abundance of liqui-

dity caused by the r apid easing of monetar y policy as inflatio-

nar y pr essur es abated in the 19 80s, and by the shar p r ise in

the supply of bank lending br ought on by incr eased compe-

tition among the banks. This led to the for mation of stock

mar ket assets and pr oper ty bubbles, which bur st following a

r ise in Japanese and global inter est r ates. In par ticular , non-

banks had taken advantage fr om cheap capital and the steep

r un-up in their mar ket valuations to r aise their bank

bor r owings, which significantly suppor ted gr owth via an

appr eciable r ise in investment. These bor r owings wer e faci-

litated by the special natur e of Japan' s pr oductive set-up,

featur ing extr emely str ong links between the industr ial

car tels ( the Keir etsu) and the financial system.

The pr oper ty and stock mar kets fell shar ply after the bubble

bur st, r ender ing the banking system insolvent. The banks,

which have histor ically been r elatively unpr ofitable, wer e

slow to clean up their balance sheets in or der to limit their

losses. Bank liquidity and the supply of cr edit dwindled as a

r esult. A non-optimum allocation of lending to unpr ofitable

fir ms

1

thus set in, while sound fir ms found themselves

star ved of liquidity. In addition, the decline in the pr ice of

pr oper ty and stock mar ket assets led to a slump in company

pr ofits and, combined with shr inking cr edit, pushed mor e

and mor e fir ms into bankr uptcy. The deter ior ation in

company and bank balance sheets, together with a lar ge

number of bankr uptcies and the tight links between compa-

nies and banks pr ompted a steep r ise in doubtful loans,

which squeezed banks' balance sheets and fur ther r estr icted

the supply of cr edit ( see Char ts 1 and 2) .

Non-banks needed to r educe their debt r apidly, their finan-

cial condition having deter ior ated sever ely in the ear ly-

1990s

2

. As a r esult, companies shar ply cut their investment

spending ( see Char t 3) , ther eby r educing their demand,

weakening the Japanese economy, and putting downwar d

pr essur e on pr ices. Consequently the r oots of Japan' s defla-

tionar y cr isis lie in companies' need to pay down their debt,

not in any weakness in household consumption. Indeed,

households have dr awn down their savings since the ear ly-

1990s

3

, ther eby compensating for the fall in cor por ate

sector demand, sustaining domestic demand and counter ing

deflationar y pr essur es.

Chart 1: J apan: doubtful loans and bank losses from doubtful loans

Source: FSA

Chart 2: J apan: bank lending to private agents

Source: OECD

Chart 3: J apan: debt and investment by private-sector non-banks

Source: Bank of Japan, National Accounts

1.2 In the United States, the same debt deflation

mechanismposes a risk, but in this case it con-

cerns households

As in Japan in the late-1980s, a similar expansion of liquidity

was obser ved in the United States fr om ar ound 2000

onwar ds. Her e, though, it was caused by highly accommoda-

(1) The banks tended to come to the rescue of defaulting borrowers to enable the latter to pay the interest due on their

debt and thus avoid the need for the banks to classify these loans as in default. As a result, bank lending was allocated

primarily to the least profitable firms, thus reducing the supply of credit to healthy companies and helping to keep

unprofitable firms in business. See "La dflation japonaise: le rle-clef du besoin d'ajustement des bilans des

entreprises" (Japanese deflation: the key role played by firms' need to adjust their balance sheets). Diagnostics Prvisions

Analyses conomiques no. 29 -February 2004.

(2) The massive investment of the late-1980s led to a huge increase in borrowing requirements, characteristic of an

economy emerging from an investment bubble.

(3) There are several possible explanations for this downtrend in the saving rate, including population ageing, a

"substitution" effect favoured by lower interest rates, and the substitution of consumption for investment in housing.

0.0%

0.5%

1.0%

1.5%

2.0%

2.5%

3.0%

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

6%

7%

8%

9%

1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

Doubtful loans held by all high street banks (lefthand scale)

Bank losses due to doubtful loans

% OF GDP %of GDP

most recent data point: 2005

-8%

-6%

-4%

-2%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

12%

14%

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006

Year-on-year

most recent data point: December 2006

70%

80%

90%

100%

110%

120%

130%

140%

12%

13%

14%

15%

16%

17%

18%

19%

20%

21%

1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006

ratioof investment to GDP gross debt of companies (righthand scale)

Bursting of stockmarket bubble

most recent data point: 2007

%of GDP

TRSOR-ECONOMICS No. 62 J uly 2009 p. 3

tive monetar y policy, accentuated by the steep r ise in global

liquidity since the beginning of the 2000s.

The for eign exchange r eser ves accumulated by the Asian

countr ies as their economies enjoyed r apid gr owth wer e

indeed absor bed by the United States. As in Japan, abundant

liquidity dr ove up the pr ices of financial and pr oper ty assets,

thus bolster ing bor r ower s' appar ent solvency and encour a-

ging fur ther lever age. This in tur n fuelled demand for assets

and, ultimately, pushed up their pr ices still fur ther , leading

to high levels of indebtedness and investment.

The r esidential pr oper ty bubble in the United States appear s

to have been compar able in scale to that of Japan. While r esi-

dential sector pr oper ty asset pr ices r ose less br utally in the

United States, they have fallen slightly faster than in Japan; the

decline seems to be similar in the commer cial sector , for the

moment, even if the United States is cur r ently r egister ing only

its fir st quar ter s of falling pr ices. On the other hand, Japan' s

financial asset pr ice bubble was mor e than ten times gr eater

than in the United States. Japanese stock mar ket assets lost

35% of their value in the space of a year following the bur s-

ting of the bubble. In the United States, meanwhile, 18

months after peaking asset pr ices lost near ly 40% of their

value

4

. This decline r eflects the weakness of the financial

system, the collapse of major mar ket player s having pr ecipi-

tated a steep fall in asset pr ices and incr eased volatility.

Chart 4: Asset prices before and after the bursting of the bubble in J apan

and the fall in asset prices in the United States

Source: Datastream, DGTPE calculations

Chart 5: Residential property asset prices before and after the bursting of

the bubble in the United States and J apan (national price indices)

Sources: FHFA (United States), Japan Real Estate Institute (Japan),

DGTPE calculations

The speculative excesses needing to be cor r ected differ ed

between the two countr ies. In the United States, easier access

to cr edit ( fuelled by expectations of r ising pr oper ty pr ices

and the emer gence of financial pr oducts designed to r educe

r isk exposur e) led to a shar p expansion of the mor tgage

mar ket. This tr igger ed a massive r ise in household debt,

without affecting investment by non-banks, which appear to

be in sound financial condition.

The US pr oper ty pr ice bubble bur st as a r esult of slowing

demand for mor tgage loans. This, together with r ising

defaults

5

, r ever sed pr ice expectations, leading finally to a fall

in pr ices. Just as pr oper ty pr ices began falling, this loan

financing mechanism gr ound to a halt. The pr oper ty cr isis

then fed thr ough to the financial sector via r ising defaults on

subpr ime loans in the mor tgage mar ket. The r ise in house-

Box 1: How deflation works

A deflationary spiral, where falling prices and demand become a self-sustaining process, is possible only if at least one of the following

three factors is at work:

Falling inflationary expectations

Households tend to postpone consumption if they think prices are going to continue to fall. This kind of wait-and-see attitude ultimately

weakens demand for goods and services provided by companies. This will lead firms to cut their output, and hence their demand for labour

and/or the wages they pay their employees. Similarly, if companies expect prices to fall, they will expect their profits to fall too; to limit the

erosion of their margins, they will reduce their demand for labour and/or cut wages. Unemployment rises and wages fall, amplifying the

economic slowdown and the fall in prices. Ultimately, falling prices and domestic demand feed on each other.

Certain over-indebted agents see their real debt rise as asset prices fall: this is known as debt-deflation

The real cost of debt rises when the price of real or financial assets falls steeply. Faced with the risk of insolvency, agents may be forced to

reduce their debt leverage. But falling collateral values leads to a drying up of the supply of credit. Sources of financing and loan repay-

ment dwindle. Borrowers seek to sell off their assets to avoid bankruptcy, further undermining asset prices. But falling prices in turn lead to

rising defaults and amplifies the rationing of bank credit. Consequently, domestic demand declines sharply leading to a fall in the general

price level.

The economy is in a liquidity trap

Here, nominal interest rates have reached a floor and can fall no further. Falling prices therefore lead to a rise in real interest rates and

monetary policy ceases to be effective as a tool for stimulating the economy. Rising interest rates tend to weaken final demand by raising

the cost of borrowing and aggravating the burden on borrowers.

In J apan, over-indebtedness was the main mechanism triggering the deflationary process, which was subsequently sustained by expecta-

tions and the liquidity trap.

(4) Japan's stockmarket continued its downward course in the 1990s, and had lost 60% of its value eight years after the

bursting of the asset bubble.

45

55

65

75

85

95

105

- 3yrs - 2 yrs - 1 yr bubblebursts 1yr 2yrs

United States (S&P500) Japan (Nikkei)

Base 100 at peak

(5) The rise in default rates in 2006 was partly the result of dearer than expected subprime loan repayments (the interest

rate on repayments is low at the start of the loan, then rises subsequently); this was compounded by the rise in the key

rate, which fed through into mortgage rates, thus strangling weaker borrowers who had borrowed at variable rates.

80

85

90

95

100

105

- 2 yrs - 1 yr and 6

mths

- 1 yr - 6 mths bubble

bursts

6mois 1yr 1yr and 6

mths

2yrs

United States (property prices) Japan (land prices)

Base 100 at peak

TRSOR-ECONOMICS No. 62 J uly 2009 p. 4

hold defaults entailed hefty losses for financial institutions,

spr eading to the entir e financial system via str uctur ed

pr oducts and "r epackaged" loans; in some ways this was

much the same mechanism as the one at wor k with doubtful

loans in Japan. Lack of tr anspar ency as to financial institu-

tions' r eal exposur e and losses br ed a cr isis of confidence in

the inter bank mar ket. This fir st mater ialised in a dr ying up

of liquidity in this mar ket, followed by a spate of failur es

among financial institutions ( most pr ominently Lehman

Br other s) . These failur es sever ely destabilised the mar kets,

cr eating additional difficulties for the banks. A vicious cir cle

then ar ose in the financial mar kets leading institutions to

delever age extensively and r ein-in their lending. The lack of

tr anspar ency as to institutions' r eal balance sheet exposur e

and losses pr ompted a wave of distr ust that sever ely

impair ed the wor kings of the global financial system, as US

mor tgage-r elated r isk spr ead wor ldwide.

Thus, the r oots of the Amer ican and Japanese cr ises wer e

basically the same, so we can imagine them having the same

deflationar y consequences. However , the deflationar y

mechanisms at wor k in the two countr ies ar e pr obably ver y

differ ent, due in par ticular to the specific modes of adjust-

ment of the labour mar ket ( in the United States, depr essed

final demand is channelled via the adjustment of employ-

ment and not via a pr ice-wage loop) and the inter national

envir onment ( the yen' s appr eciation in par ticular exer ted

additional downwar d pr essur e on pr ices) .

Chart 6: US household debt, as a % of gross disposable income (GDI)

Source: Fed

Chart 7: Private non-financial agents' debt, as a % of GDP

Sources: BoJ, Fed, DGTPE calculations

2. The main differences in the deflationary mechanisms in J apan and the United States lie in the way their labour

markets and the international environment adjust

The deter ior ation in the inter national envir onment, which

accentuated the Japanese slowdown, had a cause exogenous

to the Japanese cr isis, namely the Asian cr isis of 1997, which

sever ely hur t Japanese expor ts ( the Japanese economy' s

main dr iver ) . The cur r ent collapse in global demand for US

goods and ser vices, meanwhile, stems mainly fr om the

contagion of the Amer ican cr isis to the r est of the wor ld. The

United States, which was at the or igin of the cr isis, has r egis-

ter ed a ver y shar p contr action in impor ts due to the collapse

of domestic demand. This decline in impor ts has mor e than

offset that of expor ts caused by weaker global demand. The

US tr ade deficit has shr unk dr astically. Over all, for eign tr ade

made a positive contr ibution to US GDP gr owth in 2008 and

in the fir st half of 2009. Between 1997 and 1999, on the

other hand, because the slowdown in global demand for

Japanese goods and ser vices was exogenous to the Japanese

economy, expor ts weakened so sever ely that for eign tr ade' s

contr ibution to gr owth was nil.

The yen' s successive appr eciations in the cour se of the

1990s had alr eady depr essed pr ices still fur ther ( via

impor ts) and hamper ed expor ts as a r esult of r educed

competitiveness. This phenomenon was exacer bated by the

fall in global demand for Japanese goods and ser vices dur ing

the Asian cr isis. The United States, on the other hand, is not

suffer ing fr om an adver se cur r ency movement, since the

dollar weakened when the US enter ed r ecession in the four th

quar ter of 2007, helping to sustain activity.

In Japan, the labour mar ket adjustment in r esponse to

shar ply r educed domestic demand and, ultimately, GDP,

occur r ed via wages, wher eas in the United States the bur den

appear s to be falling mor e on jobs. In Japan, wages ar e

downwar dly flexible in times of cr isis: Japanese tr ade unions

have an implicit total employment tar get and hence will

agr ee to wage cuts when th e economy slows, to pr event

unemployment fr om r ising unduly ( unemployment did not

exceed 3. 5% until the end of the 1990s) . Consequently,

lower bonuses and r educed over time wor king tr aditionally

ver y substantial was one of the main lever s activated by

employer s to adjust wages downwar ds. Wages had alr eady

begun to slow at the beginning of the cr isis, but the downtur n

in activity in 1997 and its impact on domestic demand this

time led them to fall significantly.

This exer ted negative pr essur e on pr ices ( see Char t 8) ; these

had alr eady come under deflationar y pr essur e with the

opening up of emer ging Asian countr ies

6

and their falling

expor t pr ices.

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

120%

140%

1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008

Aggregate Mortgage Consumer borrowing

Most recent data point: Q1 2009

0%

50%

100%

150%

200%

250%

Japan United States

Q-10ans Q(bursting of strockmarket bubble)

(6) Deregulation opened up markets to foreign manufactures, whose share of total imports rose from 23% to 59%

between 1980 and 1995.

TRSOR-ECONOMICS No. 62 J uly 2009 p. 5

Chart 8: Wages and inflation in J apan

Sources: Datastream, DGTPE calculations

In the United States, on the other hand, wages ar e bar ely

cyclical at all, and have not r eally slowed since the onset of

the cr isis. Employment has been the labour mar ket' s adjust-

ment var iable, her e. Consequently, while a pr ice-wage loop

looks less likely in the United States than in Japan, r ising

unemployment could never theless depr ess final demand and

weigh on pr ices indir ectly. The main differ ence is that the

deflationar y mechanism could be less dir ect in the United

States than in Japan.

Ther e is, mor eover , a fundamental deflationar y component

in Japan that is appar ently absent in the United States, namely

an economic policy inappr opr iate to the sever ity of the cr isis.

Chart 9: Inflation and the labour market in the United States

Source: BLS

3. US policy appears better suited than J apanese policy to countering the risk of deflation

3.1 The J apanese authorities were slow to react

The Bank of Japan ( BoJ) went on r aising its r ates after the

financial bubble bur st, which helped to weaken the banking

system. Not until the explosion of the pr oper ty cr isis ( one

year after that of the stockmar ket bubble) did it begin to

lower its key r ates, and it took mor e than five year s to cut

them to 0.5%. Rate cutting pr oved insufficient to avoid a

wave of bankr uptcies among financial institutions, alr eady

weighed down by heavy losses.

However , this monetar y policy pr oved ineffectual, since the

cr edit channel was blocked ( the banks' balance sheets wer e

too weak for a cr edit-led stimulus. Cr edit r ationing set in

fr om 1998 onwar ds, while negative inflation dr ove up r eal

inter est r ates, cr eating a liquidity tr ap that fur ther bolster ed

the deflationar y spir al ( see Box 1) . This situation stemmed

lar gely fr om the length of time the banks, the gover nment

and the BoJ

7

took to acknowledge the impor tance of the

question of doubtful loans and addr ess it.

-6%

-4%

-2%

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

wages (y-o-y quarterly moving average inflation (y-o-y)

VAT is increased

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9 -1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008

inflation per capita average wage unemployment rate (righthand scale)

Y-o-y in % %

Most recent data point: Q1 2009

Box 2: J apanese crisis timeline

Source : DGTPE

+2 yrs

1

s t

fi scal

st imulus

Heavy banking

losses and ba nk

fail ur es + ri si ng

unemployment

Act ivi ty slows Pr ices sl ow

+3 yrs

+1 yr

Wave of

cor porat e

bankr uptcies

Propert y bubbl e burst s

Key r ates cutti ng

Recession

+8 yr s

(1998)

Sev ere fi nancial cri sis :

banks nati onal ised ; fi rst

measures to rescue

fi nancial system

Dual shock: tax

shock and Asi an

cri si s

Financi al bubbl e

bursts

Q4

1989

Deflat ion

BoJ pursues zer o

inter est r ate pol icy

Phase 1: Economy weakens , 19901997

Phase 2: Deflation

takes hold, 19981999

Ph as e 3: Defl ati onary spi ral

20002003

+10 yr s

BoJ i mplements

unconventi onal

monetary pol icy

(7) Japanese law lays down three definitions for doubtful loans. The first, and the first associated data, did not come into

being until 1993 and after, while the other two definitions were not introduced until 1999, following the "Financial

Reconstruction Bill", i.e. nine years after the onset of the crisis (see "Non performing loans and the real economy:

Japan experience", Inaba et al, 2005 - Bank for International Settlements 22-07 pages 106-27).

TRSOR-ECONOMICS No. 62 J uly 2009 p. 6

The pr oblem did not come to the for e until Japan was on the

br ink of systemic cr isis. This was symptomatic of the Japa-

nese cr isis and is one of the key factor s contr ibuting to its

extr aor dinar y dur ation.

The Japanese gover nment unveiled ten stimulus plans

between 1992 and 2000, for a cumulative amount r epr esen-

ting ar ound 27% of GDP and split r oughly evenly between

r eal budgetar y spending and financial measur es such as life-

lines for the banks and cr edit facilities for SMEs. For a var iety

of r easons, however , these plans pr oved ineffectual in view

of their official size ( see Box 3) .

Chart 10: J apan's monetary policy response to the bursting of the asset

price bubbles

Source: OECD

So it looks as if the appr opr iate economic policy was not

applied until too late: ex post, the Fed' s models

8

show that a

mor e significant r ate cut befor e 1995 and a mor e accommo-

dating fiscal policy would have pr evented Japan fr om falling

into deflation. It has only been possible to establish the

belated natur e of the BoJ' s action ex post. Ex ante, in their

ignor ance of the banking system' s difficulties and compa-

nies' fr ailty, together with over -optimistic for ecasts of infla-

tion and activity, analysts consider ed the monetar y policy

r esponse to be appr opr iate.

It was not until 1998 and after war ds, r eally, that vigor ous

steps wer e taken to stem the financial cr isis ( see Table 1) .

Taken together with the BoJ' s zer o inter est-r ate policy and

quantitative measur es fr om 2001 onwar ds ( see Box 4) ,

these steps slowly succeeded in pur ging the mar ket of bad

debts and clear ing up the cr isis. However , the financial

system' s super visor y author ity failed to pur sue the bank

stabilisation measur es thr ough to their conclusion

9

, and it

was not until 2003 that the gover nment pr oceeded to buy up

all doubtful loans ( see Char t 1) . Zer o inter est r ate policies

followed by quantitative easing successfully modified agents'

expectations as to the time fr ame for futur e shor t-ter m r ates;

this did push down long r ates a little, but their ability to

r evive lending in Japan and shor e-up inflationar y expecta-

tions, on the other hand, was at best ver y slow to mater ialise.

Source: DGTPE

Indeed, the str ong gr owth in the monetar y base did not

pr oduce a sufficient incr ease in money supply, since the

banks did not alter their lending behaviour in consequence

( the monetar y multiplier being ver y weak) and expanded

their holdings of safe assets. The r elative ineffectiveness of

monetar y policy can also be accounted for by the fact that the

BoJ' s expansionar y policy lacked cr edibility. Indeed, in

2000, with deflation in full swing, the BoJ fir st r aised its

r ates, then cut them shor tly after war ds, and it was not until

2003 that the BoJ began communicating clear ly about how it

planned to exit fr om quantitative easing

10

.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002

Key rate

%

Financial bubble

bursts

Property bubble

bursts

Box 3: Why J apan's fiscal stimulus was ineffectual despite its scale

Of all of the J apanese government's stimulus plans (amounting to a cumulative 27% of GDP, roughly), growth-boosting measures repre-

sented only 1/3

a

of the total amount, on average (or a cumulative 10% of GDP, roughly). The macroeconomic effectiveness of these measu-

res was also impaired by lags in implementing them and their overly limited scopewhen not counteracted by restrictive counter-

measures. That is because one-off fiscal consolidation measures are reckoned to have counterbalanced the positive effects of stimulus

plans, plunging J apan into deflation in 1998. The tax shock of 1997 (VAT was raised from 3 to 5%, the income tax reductions in force since

1995 were reversed, the health service patient contribution was increased, and public investment was pruned sharply) contributed to the

J apanese recession in 1997/1998. In particular, over and above the temporary positive shock to inflation, the VAT rate hike pushed prices

into negative territory as consumption plummeted. Other possible explanations of these plans' ineffectiveness are that the measures were

poorly targeted (being aimed at underperforming sectors), and that a liquidity trap emerged.

a. "Fiscal policy works when it is tried", Adam Posen, Institute of International Economics, 1998.

(8) Alan Ahearne et al: "Preventing Deflation: Lessons from Japan's Experience in the 1990s," International Finance

Discussion Papers no. 729; 2002.

(9) What is more, the bank stabilisation measures implemented in 1998 and after were sub-optimal: two public liquidity

injection programmes were applied in parallel to the public deposit guarantee mechanism, but the counterparts

demanded by the authorities were never provided, which created moral hazard and did not encourage the banks to

speed the structuring of their assets, declare bankruptcy, or reveal their losses.

Table 1: J apan: economic and monetary policy measures

to rescue the financial systemfrom1998onwards, in

percentage points of 2000GDP

Public equity injections 2.5

Guar antees to banks 3.7

Cr eation of defeasance str uctur es to pur chase

doubtful loans ( in 1999 and 2003)

2.0

Gr anting of loans at differ ential r ates to tr oubled

banks

1.0

Pur chase by BoJ of shar es fr om banks 0.4

TOTAL 9.8

(10) The conditions for exiting from quantitative easing were that year-on-year inflation of non fresh-food prices (Core

CPI) had to be positive over several months and that forecasts should not be negative. Krugman explains that these

conditions were not sufficiently binding and that, for the expansionary monetary policy to be truly credible, the BoJ

would have had to adopt a 4% inflation target over 15 years, versus a 0% inflation target during the years of

quantitative easing: "It's back: Japan's slump and the return of the liquidity trap", Krugman, Brookings Papers on

Economic Activity, vol. 29 (1998-2) pages 137-206; 1998).

TRSOR-ECONOMICS No. 62 J uly 2009 p. 7

3.2 The United States has learned the lessons of

the J apanese crisis

3.2.1 A highly aggressive monetary policy

The Amer ican author ities appear to have managed the cr isis

mor e r esponsively and mor e ener getically. They began inter -

vening in the monetar y spher e str aight after the bur sting of

the pr oper ty and financial bubble, wher eas the BoJ had

waited until the bur sting of th e pr oper ty bubble, one year

after the financial bubble bur st. But r ight fr om the star t of

their monetar y inter vention, the United States and Japan cut

their r ates at a compar able pace ( r espectively 500 pb ver sus

460 pb over the following 21 months ( see Char t 7) .

However , the Fed took less than two year s to cut its r ate to

zer o, compar ed with eight year s in Japan, wher e the key r ate

had been higher when the bubble bur st..

As a stop-gap measur e to offset any br eakdown in financing

to the economy, the "financial system stabilisation plan" also

pr ovides for mor e dir ect measur es in the for m of loans to

banks and r ecapitalisations. But this plan also pr ovides

dir ect suppor t for lending to households and small busi-

nesses, contr ibuting mor e than $ 100 billion to the Fed' s

TALF pr ogr amme

11

. The Fed, meanwhile, has come up with

an ar r ay of new cr edit instr uments to help pur sue its mone-

tar y easing and keep the pr imar y and secondar y mar kets

liquid. This policy is descr ibed as cr edit easing ( see Box 4) .

Another of the Fed' s objectives was to br ing down long-ter m

r ates. The implementation of "unconventional" measur es

such as pur chases of Mor tgage Backed Secur ities, secur ities

of gover nment-sponsor ed enter pr ises ( GSE)

12

and US

Tr easur y bonds, br ought about a substantial fall in long-ter m

mor tgage r ates, to some extent holding in check the r ise in

10-year gover nment bonds, and a depr eciation of the dollar .

Although the situation appear s to have impr oved wher e liqui-

dity is concer ned, the imper ative need is to r estor e the cr edit

channel to nor mal once mor e, this being the main instr u-

ment of monetar y policy and the indispensable means of

financing to business and households.

Chart 11: Monetary policy response after the bursting of the J apanese and

US property bubbles

Sources: BoJ, Fed, DGTPE

The Fed' s intr oduction of a pur e money cr eation mechanism

ser ves to cur b deflationar y expectations, since these

measur es should have an inflationar y impact once activity

picks up. Agents' expectations could then shift fr om deflatio-

nar y to inflationar y, unless agents expect inter est r ates to r ise

once the cr isis is over , in which case the policy of money

cr eation would be ineffective as a means of anchor ing expec-

tations.

Box 4: Unconventional monetary policies in J apan and the United States

Between 2001 and 2006, more than a decade after the outbreak of the crisis, J apan took unconventional policies measures described as

quantitative easing, substituting a balance sheet size objective for an interest rate objective. This policy was liabilities-oriented, using open-

market operations to achieve a quantitative target (revised upwards several times) via the current accounts of the J apanese private-sector

banks on the liabilities side of the BoJ balance sheet. The central bank also expanded the modus operandi of its interventions to include

purchases of treasury bonds and, from 2002 onwards, equities, ABS and commercial paper. In addition, the Finance Ministry intervened

heavily in the foreign exchange markets in 2003 and 2004. While this policy did curb the yen's appreciation and provided cheap, abundant

funding to the banks, it does not appear to have any major impact on activity

a

.

The Fed's policy, described by its Chairman as credit easing, concentrates more on the central bank's assets. The Fed is seeking to act on

several segments of the capital markets (commercial paper, MBS, Treasury paper, etc.) by purchasing securities. This is swelling the central

bank's assets, the purchases being financed by the creation of money moreover (the central bank credits the accounts of the banks selling

these securities). The very large number of loans made against more-or-less high-quality collateral has sharply expanded the Fed's balance

sheet.

a. See Trsor Economics no. 56: Unconventional monetary policies, an appraisal, and IMF, 2009 Gauging risks for deflation.

(11) Term Asset Backed Securities Loan Facility: this programme supports the issuance of ABS (Asset Backed Securities)

collateralised by student and car loans, etc. and provides for loans to holders of certain triple-A rated ABS assets.

(12) Government Sponsored Enterprises are public/private entities specialising in mortgage loans to households generally

regarded as risky. The best-known GSEs are Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

- 2 yrs - 1 yr property

bubble bursts

1 yr 2 yrs 3 yrs 4 yrs

Japanese key rate USkey rate

%

Japanese

financial bubble

bursts

US financial

bubble bursts

TRSOR-ECONOMICS No. 62 J uly 2009 p. 8

Publisher:

M inistre de l conomie,

de l I ndustrie et de l Emploi

Direction Gnrale du Trsor

et de la Politique conomique

139, rue de Bercy

75575 Paris CEDEX 12

Publication manager:

Philippe Bouyoux

Editor in chief:

Jean-Paul DEPECKER

+ 33 (0)1 44 87 18 51

tresor-eco@ dgtpe.fr

English translation:

Centre de traduction des minis-

tres conomique et financier

Layout:

M aryse Dos Santos

I SSN 1777-8050

R

e

c

e

n

t

I

s

s

u

e

s

i

n

E

n

g

l

i

s

h

J uly 2009

No. 61. The Revenu de Solidarit Active or earned income supplement: its design and expected

outcomes

Clment Bourgeois, Chlo Tavan

J une 2009

No. 60. China, laboratory to the world?

Alain Berder, Franois Blanc, J ean-J acques Pierrat

No. 59. Distributable surplus and share-out of value added in France

Paul Cahu

May 2009

No. 58. Survey of household confidence and French consumer spending

Slim Dali

No. 57. Foreclosures in the United States and financial institutions losses

Stphane Sorbe

http://www.minefe.gouv.fr/directions_services/dgtpe/TRESOR_ECO/tresorecouk.htm

3.2.2 A more effective fiscal policy

As in Japan, Amer ica' s fiscal policy is heavily skewed towar ds

pr oviding shor t-ter m suppor t for final demand ( via tax

cr edits for households, pr ivate investment gr ants, public

investment, etc.) . Contr ar y to the Japanese exper ience,

however , the Amer ican stimulus plans may pr ove mor e effec-

tive. The $787 billion Amer ican stimulus plan, r epr esenting

5.5% of GDP and passed in Febr uar y 2009, coming on the

heels of the Febr uar y 2008 stimulus plan r epr esenting 1.2%

of GDP, consists of suppor t for consumption and help for

households in difficulty ( 39% of the plan, r epr esenting 2.1%

of GDP) ; 34% of the plan ( 1.9% of GDP) is intended for

investment in public infr astr uctur e investment, R&D ( in

science and ener gy) , and human capital; the r emaining 27%

( 1.5% of GDP) is mainly ear mar ked for help to States and

local gover nments, lar gely to fund Medicaid and Medicar e

pr ogr ammes

13

. Aid has also been made available for sector s

in difficulty, albeit on a r ather lesser scale; as a r esult, $55

billion ( 0.4% of GDP) was dr awn fr om the TARP

14

to come

to the aid of the car industr y.

3.2.3 Help for the financial sector

Over and above this suppor t for final demand, US monetar y

policy has displayed gr eat vigour in tackling the financial

cr isis and avoiding a Japanese-style deflationar y spir al.

In autumn 2008, the Tr easur y inter vened massively via the

TARP to r ecapitalise cer tain banks and nationalise the GSEs.

Subsequently, and in view of the inadequacy of the fir st set of

measur es, the new Tr easur y Secr etar y, Tim Geithner ,

announced a fr esh financial sector r escue plan mor e

massive, mor e ambitious, as well as better contr olled and

designed than its pr edecessor . The plan to buy up so-called

toxic assets was modified slightly ( see Box 5) . The banks'

defeasance str uctur e and the r ecapitalisation oper ations that

have taken place ar e compar able to the Japanese measur es,

but they wer e implemented far mor e r apidly.

To avoid the onset of a debt deflation spir al, the Amer ican

author ities have put in place a debt r estr uctur ing plan for

households in difficulty, in or der to stem the tide of mor tgage

defaults leading to depr eciation of asset values.

Sophie RIVAUD,

Michal SICSIC

(13) Medicaid is a programme that provides sickness insurance to low-income individuals and families. Medicare is also a

healthcare insurance programme, for individuals aged over 65.

(14) The TARP (Troubled Asset Relief Program) is a $700 billion programme created originally to purchase "toxic assets"

from the banks.

Box 5: TimGeithner's measures to tackle the financial crisis

$1,000 billion in public-private investment funds to buy up "toxic" assets;

Establishment of a stress test to assess financial institutions' capacity to withstand further losses and their lending capacity in the

event of a worsening of the crisis;

The bank supervisors, the SEC and the Treasury will persuade the banks to reveal their financial condition (i.e. their losses) in order to

improve market transparency;

A more realistic and forward-looking evaluation of financial institutions' balance sheets (Fed, FDIC, OCC and OTS).

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Assistant Labour Commissioner Question Paper With AnswersDocument17 pagesAssistant Labour Commissioner Question Paper With Answersrajsinghal90% (29)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- POSNER, Richard - Law, Pragmatism and DemocracyDocument412 pagesPOSNER, Richard - Law, Pragmatism and DemocracyLourenço Paiva Gabina100% (5)

- FTWZDocument7 pagesFTWZchandan jhaNo ratings yet

- Chief Corporate Security Officer in Dallas TX Resume Reggie BaumgardnerDocument4 pagesChief Corporate Security Officer in Dallas TX Resume Reggie BaumgardnerReggieBaumgardnerNo ratings yet

- Political and Leadership StructuresDocument30 pagesPolitical and Leadership StructuresTcherKamilaNo ratings yet

- Garrido vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 101262, September 14, 1994, 236 SCRA 450Document7 pagesGarrido vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 101262, September 14, 1994, 236 SCRA 450Angela BauNo ratings yet

- Final Exam in Advanced Financial Accounting IDocument6 pagesFinal Exam in Advanced Financial Accounting IYander Marl BautistaNo ratings yet

- Political Self: Activity: Greenhills Hostage CrisisDocument3 pagesPolitical Self: Activity: Greenhills Hostage CrisisClarisse PelayoNo ratings yet

- Pidsdps 2203Document86 pagesPidsdps 2203Charleen Chavez NavarroNo ratings yet

- Shapes de Arpejos TríadesDocument1 pageShapes de Arpejos TríadesBL Music CoordenaçãoNo ratings yet

- Strict Liability PDFDocument17 pagesStrict Liability PDFhonourtmanyofaNo ratings yet

- Press Release Jose RamirezDocument1 pagePress Release Jose RamirezKBTXNo ratings yet

- Kenya - Renew Sugar Miller RegistrationDocument5 pagesKenya - Renew Sugar Miller RegistrationIan Ochieng'No ratings yet

- The Common Law of Mankind. by C. Wilfred Jenks PDFDocument13 pagesThe Common Law of Mankind. by C. Wilfred Jenks PDFAlondra Joan MararacNo ratings yet

- Atm Corp Monetization SBLC Procedures-Updated July 2022Document3 pagesAtm Corp Monetization SBLC Procedures-Updated July 2022tiero martinsNo ratings yet

- Easy Money - How To Make $25-30 by Doing Just 15 Mins of Work (Required No Investment)Document8 pagesEasy Money - How To Make $25-30 by Doing Just 15 Mins of Work (Required No Investment)samaouiNo ratings yet

- FortiOS-6.0-Hardening Your FortiGateDocument29 pagesFortiOS-6.0-Hardening Your FortiGateAkram AlqadasiNo ratings yet

- Statement of Claim Against Lafarge Canada Exshaw Cement Plant - Dec. 6, 2023Document10 pagesStatement of Claim Against Lafarge Canada Exshaw Cement Plant - Dec. 6, 2023Greg0% (1)

- UST Faculty Union v. BitonioDocument2 pagesUST Faculty Union v. BitonioAnonymous 5MiN6I78I0No ratings yet

- Boulder Ordinance 8245Document50 pagesBoulder Ordinance 8245Michael_Lee_RobertsNo ratings yet

- Wwi-Pbs Webquest11-1Document4 pagesWwi-Pbs Webquest11-1api-310907790No ratings yet

- Chapter 2: Boolean Algebra & Logic Gates Solutions of Problems: Problem: 2-1Document7 pagesChapter 2: Boolean Algebra & Logic Gates Solutions of Problems: Problem: 2-1GHULAM MOHIUDDINNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2: Organizational Plan: 2.1 Introduction To The OrganizationDocument8 pagesChapter 2: Organizational Plan: 2.1 Introduction To The OrganizationWardah MdnorNo ratings yet

- CLINICAL-III (Mohd Aqib SF) PDFDocument47 pagesCLINICAL-III (Mohd Aqib SF) PDFMohd AqibNo ratings yet

- Standar Operational Procedure Floor TeamDocument4 pagesStandar Operational Procedure Floor TeamJagadS VlogNo ratings yet

- Marcos v. Marcos, G.R. No. 136490Document9 pagesMarcos v. Marcos, G.R. No. 136490Cyrus Pural Eboña100% (1)

- 20 Years of CARPDocument132 pages20 Years of CARPNational Food CoalitionNo ratings yet

- Syllabus PG Diploma in Criminology & Forensic ScienceDocument12 pagesSyllabus PG Diploma in Criminology & Forensic SciencemanjurosiNo ratings yet

- Adong vs. Cheong Seng GeeDocument5 pagesAdong vs. Cheong Seng GeeellaNo ratings yet

- Defendant Parties ListDocument4 pagesDefendant Parties ListSEFAA GovernmentNo ratings yet