Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Business Risk Audit - A Longitudinal Case Study of An Audit Engagement

The Business Risk Audit - A Longitudinal Case Study of An Audit Engagement

Uploaded by

audria_mh_110967519Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Business Risk Audit - A Longitudinal Case Study of An Audit Engagement

The Business Risk Audit - A Longitudinal Case Study of An Audit Engagement

Uploaded by

audria_mh_110967519Copyright:

Available Formats

Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461

www.elsevier.com/locate/aos

0361-3682/$ - see front matter 2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.aos.2006.09.004

The business risk audit A longitudinal case study

of an audit engagement

Emer Curtis

a,

, Stuart Turley

b

a

Department of Accountancy and Finance, National University of Ireland, Galway, Ireland

b

Accounting and Finance Group, Manchester Business School, University of Manchester, UK

Abstract

This study examines the impact of the Business Risk Audit (BRA), a development in audit methodology imple-

mented in the late 1990s, on actual audit practice and on practitioners. Evidence is presented through a longitudinal case

study developed from a set of actual audit Wles over a Wve year period spanning the implementation of the BRA,

together with interviews with audit team members. The study contributes to our understanding of the nature of the

audit techniques underlying the BRA and the diYculties experienced in implementing them within the existing organiza-

tional structures. In addition, the study illuminates the potentially conXicting roles of audit methodology in its organiza-

tional context, both in mediating the complex relationship between the administrators and practitioners in the large

accounting Wrms and as the knowledge management structure used to support delivery of the audit product.

2006 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Introduction

The introduction of audit approaches that place

greater emphasis on the business risks in the orga-

nization whose Wnancial statements are being

audited, generally termed the Business Risk Audit

(BRA), has been documented as a major innova-

tion in audit methodology in the second half of the

1990s (Eilifsen, Knechel, & Wallage, 2001; Higson,

1997; Lemon, Tatum, & Turley, 2000). This inno-

vation has been associated with changes in the

scope of the planning and risk assessment pro-

cesses and in the related evidence gathering proce-

dures used by auditors. Proponents of the BRA

suggest that this approach has the potential to

enhance audit eVectiveness, arguing that an in-

depth understanding of a business, its environment

and the business processes through which value is

created is the best way in which an auditor will be

able to recognize management fraud and business

failure risks. Critics have suggested that the BRA

was intended to redeWne auditing as consulting and

*

Corresponding author. Tel.: +353 91 493138.

E-mail address: emer.curtis@nuigalway.ie (E. Curtis).

440 E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461

to facilitate identiWcation of opportunities for pro-

viding value added services to clients, with the

intention of improving the status and proWtability

of the auditor.

Much of the literature describing and comment-

ing on the BRA implicitly assumes that BRA as

developed has been implemented uncontroversially

by the audit Wrms. However, Power (1997, p. 8) has

drawn attention to the fact that the programmes,

ideas and concepts which shape the development

of audit practice are at best loosely coupled to the

tasks and routines performed in their name. Rad-

cliVe (1999) established a similar point when inves-

tigating the nature of the technologies used to

enact eYciency auditing. This study was motivated

by a desire to understand how the BRA translated

into changes in auditing techniques implemented

by practicing auditors and the diYculties encoun-

tered in operationalising the BRA in context, and

thus to examine the relationship between a pro-

gramme for change in the introduction of the BRA

and the set of practices which it describes.

This paper reports the results of a case study on

the implementation of the BRA on an audit

engagement. The case is based on the audit work

papers for a client of a large accounting Wrm over

the period 19962000, supplemented by interviews

with members of the audit team and reference to

the documented methodology of the audit Wrm. A

case study approach was chosen because it allowed

for an in-depth review of the nature and extent of

planning work and evidence gathering procedures.

The longitudinal aspect of the study was important

as it provided an insight into changes from the pre-

vious methodology and how changes were embed-

ded in the audit process. Interviews with members

of the audit team allowed investigation of barriers

to implementation in the organizational context. A

case study approach to investigation of the audit

process is also consistent with calls that have been

made for more research evidence from real audit

assignments about the methods that Wrms actually

use, and more recently for evidence on the practi-

cal diVerences between the application of the older

methodologies and BRA (Bedard, Mock, &

Wright, 1999; Gwilliam, 1987; Power, 2003; Rob-

son, Humphrey, Khalifa, & Jones, forthcoming;

Turley & Cooper, 1991).

In addition to contributing descriptive evidence

about the manner in which the concepts underly-

ing the BRA were operationalised, the study

explains why this methodology was perceived as

more judgemental and ambiguous by audit staV.

The case highlights diYculties experienced in

achieving a lasting move to an audit focused on

business risks and high level controls. It also dem-

onstrates reluctance by auditors to reduce levels of

substantive testing, particularly in relation to sig-

niWcant judgements and estimates, and identiWes

discomfort at practitioner level with the lack of

linkage between audit work done on business

risks and an opinion given on the Wnancial state-

ments. The wider relevance of these diYculties is

illustrated by related changes to successive ver-

sions of the global methodology of this Wrm.

A major innovation in practice such as the BRA

can be considered from a number of perspectives.

Its introduction may be seen as part of a Wrms

eVorts to create an audit product that is credible in

the market place. Here the administrative elements

of the Wrm, and more generally the auditing profes-

sion, are concerned with conceptualizing and rep-

resenting audit activity in a way that enhances its

legitimacy with clients and society. New methodo-

logy may also reXect administrators views regar-

ding a better audit, both as a structure for guiding

and controlling the eVectiveness of the work eVort

of staV and as a means of adapting the business

model associated with auditing. However, from the

perspective of the practicing auditor, the legiti-

macy of the audit process on an individual engage-

ment is something diVerent. The practitioner may

be concerned that the process not only meets Wrm

determined standards on methodology, but also

actually provides a body of evidence that the prac-

titioner believes to be valid as a basis for signing

the audit opinion and as a defensible record of the

audit process. The tension between what method-

ology seeks to authorize and promote in evidence

collection procedures and what practitioners

regard as appropriate for their opinion can create

diVerences between the oYcial approach and

what is actually done. This study is about the prac-

tical implementation of the BRA in an actual case

and as such the primary focus of analysis is on

whether and how that tension between methodo-

E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461 441

logy and practitioners views of what constitutes a

legitimate evidence process was evident in the

implementation of the new BRA methodology.

The study concludes that while the BRA was

developed by the administrative sections of the

large Wrms to address the concerns related to the

status, eVectiveness and proWtability of auditing

within those Wrms, inadequate consideration was

given to practitioners needs for what they

regarded as a legitimate audit which they could

personally be called upon to defend. As a result,

the implementation of the BRA was not associated

with the change in the overall pattern of evidence

collection that was intended. The study also raises

questions about the ability of the BRA to induce

audit teams to generate additional revenue

through providing added value for the client. This

is partly a question of whether a hierarchically

organized audit team has the skills, Xexibility and

time to generate value, but it is also a function of

the clients willingness and ability to pay for it.

The remainder of the paper is set out as follows.

The next two sections discuss theoretical perspec-

tives on audit methodology and review prior litera-

ture on the development and implementation of

the BRA. A description of the research methods

and the case context follows. The Wndings and

analysis are then divided into three sections, con-

sidering in turn: changing the focus of the audit to

business risk and the impact on the identiWcation

of risks; changes in the nature of the audit work

actually performed and the diYculties of imple-

menting change; and the impact of the BRA on

cost and revenues. Finally, the implications and

conclusions that can be drawn from the study for

our understanding of the role of methodologies in

audit practice are considered.

Theoretical perspectives on audit methodology

Prior literature presents a number of diVerent

perspectives on audit methodology. The primary

perspective, adopted by much of what is generally

referred to as mainstream audit research (Gendron

& Bedard, 2001) views auditing as technical prac-

tice. Much of this literature, in particular the audit

judgement and decision making literature (JDM),

adopts a rationalist paradigm from cognitive psy-

chology, which is based on the idea that humans,

or even societies, follow identiWable rules (Wester-

dahl, 2004). Such research sees auditor judgement

as a practice conducted by individuals who must

respond eYciently to cues in the auditee environ-

ment and make decisions accordingly (Power,

1995, p. 318). This perspective has been criticized

for ignoring the social context in which decisions

are made, where judgements are not simply the

procedural outcomes of the application of a set of

audit techniques (Kirkham, 1992). Pentland (1993)

argues that there is good reason to expect that no

amount of rationalistic analysis will ever produce a

suYcient explanation of auditor judgement (p.

619) due to the insuYciency of rule following as an

explanation of social order. The literature which

considers audit methodology in its social and insti-

tutional context recognizes at least four diVerent,

and potentially conXicting, roles for audit metho-

dology: the production of legitimacy for the pro-

fession as a whole; the production of a legitimate

set of work papers on an individual audit; a system

for controlling and directing the work of the prac-

titioners by administrative elements of the large

Wrms; and encoding knowledge into the organiza-

tional structure to assist in the achievement of the

organizational proWtability. Each of these perspec-

tives is discussed below.

Legitimacy of the profession

At the level of the profession, the ideas inform-

ing audit methodologies are reXected in auditing

standards which simultaneously provide a source

of legitimacy for the approaches applied by the

audit Wrms and a body of knowledge to justify the

claims of professional expertise. Consistent with

the norms and values of western market econo-

mies, the profession has an interest in representing

auditing as a rational, objective science. A number

of authors (Carpenter & Dirsmith, 1993; Dirsmith,

Covaleski, & McAllister, 1985; Dirsmith, Heian, &

Covaleski, 1997; Power, 1992, 1995, 2003) have

linked audit methodologies to the representation

of the auditor as a rational expert. Power (1992,

p. 59) suggests that the rise of a discourse in

audit sampling had much to do with attempts to

442 E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461

legitimate, rationalise, reinterpret and improve

practices that were already in place and in doing

so, aligned the auditing profession with revered

values of rationality and science. Carpenter and

Dirsmith (1993) view the discourse on statistical

sampling as modifying and regenerating the pro-

fessions abstract system of knowledge (Abbott,

1988).

Similarly Power (1995) has argued that in spite

of the theoretically questionable and operation-

ally ambiguous status of the audit risk model, it

has endured because it replaces statistical sampling

in providing an abstract foundation for audits, it

functions to rationalize a reorganization of audit

work and a reduction of detailed testing, and it

provides a respected vocabulary through which

operational decisions can be justiWed (p. 331).

Legitimacy at the level of audit practice

It is in the domain of actual practice that formal

audit methodologies are translated or transformed

into audit procedures by individual practitioners

coping with such everyday exigencies as client

pressures and the cost of performing audits (Car-

penter & Dirsmith, 1993, p. 45). The potential for

review of the audit work papers by the courts or

peer reviewers translates on an individual audit

into a need for the production of a set work papers

which are a culturally legitimate, formal, defend-

able record of the audit process (Power, 2003).

Thus audit methodology is seen to play a signiW-

cant role in the production of a legitimate set of

audit work papers. Dirsmith et al. (1985, p. 57)

suggest that the production of work papers is a

sanitizing process, where audit evidence can be

viewed as a symbol for legitimizing a neither

wholly rationalized nor rationalizable audit pro-

cess. In lamenting the trend toward more struc-

tured audit methodologies, it has also been argued

that this need to maintain legitimacy is a major

obstacle to a judgemental, organic audit:

It may well be that the litigious, control-

directed, sociopolitical environment of the

auditing profession is intolerant of the

organic audit perhaps the profession has

presented a formal image of itself that is not

reXective of its own variety or loosely cou-

pled nature. (Dirsmith & McAllister, 1982, p.

227).

This suggests that audit work papers must con-

form to institutionalized prescriptions of what

auditors do, in order to portray a rational func-

tional image of the audit (Dirsmith et al., 1985).

Thus if society expects that auditors conWrm

receivables then this must be done regardless of

eYciency or eVectiveness considerations.

Audit methodology and the control of practitioners

The large accounting Wrms, or more accurately,

professional service Wrms, are so big that the litera-

ture has recognized the separation of the adminis-

trative structure of these Wrms from the

practitioners (Carpenter, Dirsmith, & Gupta, 1994)

and the potential for conXict and power struggle

between the two (Freidson, 1986). The acknowl-

edgment of the separate roles of the administrators

and practitioners is important in considering audit

methodology because methodology is generally

developed by the administrative element but is

implemented by the practitioners. Prior literature

suggests that these two groups have diVerent inter-

ests, power bases and concepts of a legitimate pro-

cess, which results in signiWcant scope for tension

and controversy over methodology.

Administrators have primary control over rules

and resources in these organizations, allowing

them to formulate the procedural and substantive

rules addressed to the way professional work is to

be performed and to establish the basis for con-

trolling and evaluating the work of practitioners

(Freidson, 1986, p. 215). Carpenter et al. (1994)

attribute the trend towards structured audit

approaches in part to eVorts by administrators to

control local practitioner judgement:

Administrators, preoccupied with the political

and economic forces their organizations face,

focus on formulating procedural and substan-

tive rules that control the way in which the

professional work is performedThey serve

not primarily the client or even the profes-

sional practitioner, but their own organiza-

tion, and it is from this organization that they

E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461 443

derive their power and authority. Thus,

administrators seek to encode expertise into

the formal structure of the organizations by

way of its rule systems (Carpenter et al., 1994,

p. 373374).

Audit methodology and the business model

The literature also suggests that administrators

use audit methodologies to inXuence the manner in

which their organizations generate proWts. Given

the concern with proWtability in a competitive mar-

ket for audit service, where audit fees and margins

have been under pressure since the 1980s, adminis-

trators have used audit methodology in branding

and marketing their services to existing and poten-

tial audit clients (Jeppesen, 1998). Morris and

Empson (1998) suggest that the large audit Wrms

have codiWed organizational knowledge in the

form of highly structured audit methodologies,

which allows them to use inexperienced staV to

apply this codiWed knowledge, thereby facilitating

a hierarchical organization structure, to achieve

above average proWts. There are also suggestions

that audit methodologies can facilitate the expan-

sion of low value-added audit services into the pro-

vision of more lucrative consulting services by

directing audit work and the attention of audit

staV towards opportunities to provide value added

services in the course of, or as a result of, the audit

(Barrett, Cooper, & Jamal, 2005).

Thus prior literature illustrates that audit meth-

odologies serve diVerent roles at diVerent levels in

the institutional environment. The recognition of

these diVerent roles suggests that there is consider-

able scope for tension and controversy when there

is an innovation in a methodology such as BRA,

which is developed by administrative elements of

the Wrms but implemented by individual practitio-

ners.

Administrators, by virtue of their position in the

institutional environment, are more generally con-

cerned with issues such as the jurisdiction and

power of the profession, and the inXuence of their

own Wrm within that environment. They have an

interest in the role of audit methodology in the

production of legitimacy at the level of the profes-

sion. Practitioners on the other hand derive their

power and status within the Wrm primarily from

their client base (Freidson, 1986), and have the ulti-

mate power to decide on the nature and extent of

audit procedures actually performed on an individ-

ual audit. Importantly, on the individual audit

practitioners are more concerned, not with the

legitimacy of the Wrms methodology or of the pro-

fession, but with the conduct of what they regard

as a legitimate audit process, for which they take

personal responsibility. Both the Wrm and the indi-

vidual auditors within it have a common interest

that the process captured in the Wrms methodo-

logy should produce a legitimate audit Wle. How-

ever, in the context of a speciWc audit the

practitioner may divert from or add to strict appli-

cation of methodology in order to satisfy his/her

own perceptions of a legitimate evidence process.

While administrators may attempt to use audit

methodologies to organize the manner in which the

Wrm produces proWts, and control and direct work

performed by practitioners, the literature recognizes

that idiosyncratic, local and intuitive judgements

by seasoned practitioners are diYcult to manage

from the centre of the Wrm (Power, 2003, p. 381).

Practitioners must also apply the various

rules and guidelines, and in so doing trans-

form them as inXuenced by their own judge-

ment and the day-to-day exigencies of speciWc

client service work. Importantly, practitioners

employ the overly formalized rules prescribed

by administrators inconsistently and infor-

mally (Carpenter et al., 1994, p. 373374).

A number of Weld studies of auditing illustrate

this point. Fischers (1996) study of innovation in

audit technologies suggests that the administra-

tors eVorts to change highly institutionalized audit

practices will not succeed unless practitioners can

be convinced of the validity and suYciency of the

evidence produced by the new technologies. Resis-

tance of practitioners to the imposition of highly

structured client acceptance tools and methodolo-

gies has been reported by Dirsmith and Haskins

(1991) and Carpenter et al. (1994). Examining the

imposition by administrators of a system of man-

agement by objectives, Dirsmith et al. (1997) and

Covaleski et al. (1998) illustrate how this system

was appropriated by the practitioners to advance

444 E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461

the interests of their own protgs. Study of diY-

cult client acceptance decisions in large Canadian

Wrms suggest that in spite of highly formalized pol-

icies put in place by administrators, the decision

processes of practitioners remain largely Xexible

and organic (Gendron, 2001). More recently, Bar-

rett et al. (2005) report variations in the manner in

which local oYces implement both inter-oYce

instructions and global audit methodologies. How-

ever, prior Weld studies do suggest that administra-

tive elements of audit Wrms are successful in

inXuencing the logics of action (Gendron, 2002)

or world theories (Dirsmith & Haskins, 1991)

adopted by the practitioners. In other words, the

structures put in place by administrators, whether

audit methodologies, performance measures or cli-

ent acceptance tools, inXuence decision processes

by providing auditors with an interpretative

scheme and a vocabulary that they frequently refer

to when making decisions (Gendron, 2002, p.

661). Overall this literature suggests that while

administrators can potentially use audit methodo-

logies to inXuence practitioner actions on audits,

the ultimate decision as to the nature and extent of

audit testing remains with the practitioners.

The business risk audits: an ambitious programme of

change

The introduction of BRA in the second half of

the 1990s has been reported as a major innovation

in audit methodology (Eilifsen et al., 2001; Higson,

1997; Lemon et al., 2000). Higson (1997, p. 213)

presents one of the earliest papers heralding the

BRA. He suggests that as a result of the pressures

faced by auditors from many quarters, they have

been reassessing what the audit is trying to achieve

and this has resulted in an extensive questioning of

how it should be done. Knechel (forthcoming)

suggests that BRA resulted from a culmination of

pressures on auditors in the form of fee and cost

pressure and the questioning of conventional wis-

dom in audit practice, in particular questioning of

the beneWts of structured audit approaches.

The BRA was intended to widen the focus of

the auditor, from audit risk, deWned with reference

to Wnancial statement error, to business risk, deW-

ned as the risk that an entity will fail to meet its

objectives (Eilifsen et al., 2001; Higson, 1997;

Lemon et al., 2000). The proponents of the BRA

argue that business risk ultimately translates into

risk of Wnancial statement error and, therefore,

that an approach which focuses on understanding

a business, its environment and business processes

provides the best means by which an auditor will

recognize risks associated with management fraud

and business failure (Erickson, Mayhew, & Felix,

2000). Thus:

Wrms had concluded that perceived audit fail-

ures result not from the ineVectiveness of

procedures in detecting misstatements but

because of diYculties, for example in recog-

nizing going concern problems or identifying

fraud, arising from other aspects of the busi-

ness context (Lemon et al., 2000, p. 12).

It was also argued that in the modern audit

environment, where the Wnancial accounting sys-

tems are generally very good, extensive testing of

details, in the absence of a good understanding of

business risk, is at best ineYcient and at worst

ineVective. This view is consistent with the views of

critics of structured audit approaches, who have

long argued that an in-depth understanding of the

business underpins a thoughtful, Xexible and judg-

emental audit.

The change in approach envisaged by the BRA

was to be achieved in two ways: Wrst by changing

the focus of the audit from Wnancial statement risk

to business risk; and second by changing the

nature of audit testing from large volume tests of

details to the testing of high level monitoring or

supervisory controls, supported by high precision

analytical work (Higson, 1997; Knechel, 2001,

forthcoming; Lemon et al., 2000). The approach

encourages the auditors to view the client in terms

of key business processes, and risks and controls

within those processes, as opposed to a framework

based on Wnancial statement balances and transac-

tion streams. The rationale for this approach sug-

gests that if the auditor can identify the sources of

business risk and ensure that the client has appro-

priate systems to monitor and manage that risk,

there is little value in extensive substantive testing.

It has also been suggested that obtaining such an

E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461 445

insight on the business provides auditors with a

better basis for generating useful feedback for the

client. This added value contribution of BRA

has been reported both from views held by practi-

tioners within Wrms (Higson, 1997) and from the

many references to adding value on the large Wrms

websites around the time of the implementation of

the BRA (Jeppesen, 1998).

Some authors have questioned whether the

motivation for the introduction of BRA was

related to the delivery of more or better audit assur-

ance or the pursuit of self-interested proWtability

and status for the auditors themselves. During the

period from 1980 to the mid 1990s, the market for

audit services was characterized by increasing com-

petition and fee pressure. This environment led to

the development of highly structured methodolo-

gies, designed to minimize costs and maximize the

leveraging of audit work to inexperienced staV. The

consequent commoditization of the audit resulted

in the progressive diversiWcation of audit Wrms into

more proWtable consulting services. The growth

and proWtability of these consulting services in the

booming economies of the mid 1990s contributed

to an undermining of the status of audit practitio-

ners in the large professional service Wrms (Robson

et al., forthcoming).

Given this context, Robson et al. (forthcoming)

argue that the BRA sought to improve the status

of the auditor, both within the large accounting

Wrms, and externally with clients and potential

recruits, by aligning the auditor with the higher

status function of management consulting. This

perspective is supported by evidence of the strate-

gies designed to sell the BRA both inside the Wrms

to the practitioners, and outside to clients, regula-

tors and academics (Bell, Marrs, Solomon, & Tho-

mas, 1997; Jeppesen, 1998; Winograd, Gerson, &

Berlin, 2000).

Jeppesen (1998) argues that changing the focus

of the audit from Wnancial statements to the busi-

ness resulted in the audit being redeWned in order

to justify the delivery of proWtable management

consulting services with the consequent erosion of

auditor independence. In fact, Power (2003) has

suggested that the BRA approaches were driven

more by revenue than by cost considerations, given

the potential of added value to the client to gener-

ate revenue either through better recoveries on

audit fees or through the cross selling of other ser-

vices. In the context of the booming economic

environment of the 1990s, revenue generation may

have presented a more lucrative and less painful

option than seeking further eYciencies in the audit.

At the same time, litigation posed a far greater

threat to the economic survival of the large audit

Wrms than price competition, as borne out by the

fate of Andersen. Some Wrms believed that the

BRA would beneWt their own management of

engagement risk (Lemon et al., 2000). The widely

reported introduction by the large accounting

Wrms in the early 1990s of procedures to assess

engagement risk is symptomatic of the Wrms con-

cern with audit eVectiveness. It is well established

that auditors are primarily exposed to litigation

risk in the case of business fraud or business fail-

ure. Assuming that fraud and failure risks could be

appropriately identiWed by the BRA, anticipated

reductions in substantive procedures were unlikely

to result in increased exposure to litigation. To the

extent that the BRA was to be underpinned by

stringent engagement risk management procedures

within the audit Wrms (Higson, 1997; Lemon et al.,

2000), clients with high levels of business risk and

poor control environments, which are unsuitable

for this audit approach, would also be excluded

from the client base.

From programme to technology: transforming the

BRA in practice

As a response to the contextual pressures dis-

cussed above, the introduction of the BRA can be

seen as relevant to a number of the theoretical

interpretations of the role of methodology outlined

in the previous section, such as maintaining the

legitimacy of the professional activity of auditing

and changing the business model for audit. If the

BRA was intended to improve the proWtability and

status of the auditor through delivery of a diVerent

product to the client, with a reduced litigation risk

for the auditor, then it represented an ambitious

programme for change. Re-branding a tired audit

product by updating the language and the image of

the audit will neither insulate the auditor against

litigation nor deliver added value to the client.

446 E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461

While managing the image of audit practice may

not require change in practice, an impact on proWt-

ability and litigation risk does. Therefore, to

achieve their objectives Wrm administrators needed

to induce real change in audit techniques. How-

ever, earlier discussion of the potential tensions

between diVerent roles played by audit methodol-

ogy draws attention to fact that practical imple-

mentation of the new methodology required

negotiation with practitioners. A programme

designed to change audit methodology in order to

improve the status, proWtability and legitimacy of

audit practice is not necessarily consistent with the

production of a culturally legitimate audit Wle. This

represented an ambitious programme for two rea-

sons. First, in the institutional environment the

BRA faced a battle for credibility amid signiWcant

skepticism from regulators and academics (Curtis

& Turley, 2005). Second, beneath that issue lay a

separate battle at the level of audit practice: to

transform the BRA into practical changes in

highly institutionalized audit techniques, in a cli-

mate of practitioner resistance to control by

administrators (Covaleski, Dirsmith, Heian, &

Samuel, 1998). It is this battle that is essentially the

subject of this study.

The transformation of an innovation in audit

methodology into implemented practice cannot be

assumed as unproblematic. Power (1997), drawing

on Rose and Millers (1992) distinction between

programmes and technologies, suggests that the

programmes, or ideas and concepts which shape

the mission of audit practice, may be only loosely

coupled to the procedures performed in their name

(p. 8). This distinction is useful in clarifying the ten-

sions between diVerent roles played by audit meth-

odology in the production of diVerent types of

legitimacy. In particular, practitioners perceptions

regarding what is a legitimate, visible and defensi-

ble evidence process may help to explain how such

loose coupling can arise. This study was, therefore,

motivated by a desire to understand how the BRA

resulted in changes (if any) in auditing evidence

techniques employed by practicing auditors

(Power, 2003; RadcliVe, 1999).

To understand the translation between pro-

gramme and practice, it is not suYcient to look

simply at oYcial descriptions of the techniques put

forward by the Wrms or to count the number of

invoices vouched under diVerent methodologies.

The implementation of auditing techniques cannot

be considered in isolation from the audits

performed and the organizational context in which

the methodology is implemented. To provide direct

evidence on implementation and changes in

practice, the remainder of this paper analyses a

case study of an actual audit engagement, con-

structed from the audit work papers over a Wve

year period during which the BRA was introduced,

together with interviews with members of the audit

team.

Research methods

Preparation for conduct of the case study began

with a preliminary meeting in one of the oYces of

the accounting Wrm that was the subject of this

study, to review the guidance materials provided to

audit staV, have discussion with the partner (here-

after P1) responsible for implementing the new

methodology, and review a set of client Wles with a

senior (hereafter S1) to explain how the BRA had

been operationalised. A second preliminary meet-

ing in a second oYce comprised discussion with a

partner (hereafter P2) involved in the development

of the methodology on a worldwide basis, further

review of the detailed staV guidance and a discus-

sion of implementation issues. It became apparent

at this meeting that the methodology had evolved

through a number of versions and it was therefore

considered that a longitudinal perspective would

provide the best insight into the manner in which

the BRA had been implemented.

The speciWc case to be investigated was chosen

in conjunction with P2, who authorized access to

the work papers. In selecting the client, three fac-

tors were considered to be important. First, the

case had to be of suYcient size and complexity to

ensure that the change in methodology would be

evident in the work papers. Second, the client

ought not to be so complex as to render it overly

time consuming to understand the audit Wles as

Weld work for data collection was limited. Third,

E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461 447

the clients Wnancial condition ought to be suY-

ciently stable to ensure that any changes in the

nature and extent of the work were primarily

related to the implementation of the BRA rather

than to changes in the companys condition. A cli-

ent operating in the wholesale/distribution indus-

try was chosen. This company had been a client for

in excess of 10 years and had experienced steady

growth throughout the Wve-year period of the case

study. The client also had the advantage of consid-

erable continuity within the audit team during this

period. A span of Wve years was chosen because the

BRA had been Wrst implemented for this client for

the audit of the Wnancial statements for the year

ended 31 December 1997. Hence 1996, being the

Wnal year of the old methodology, was included.

The most recent audit completed at the time of the

Weldwork was for the year ended 31 December

2000.

Collection of evidence took place in the audit

Wrms oYces. Access was provided to: all of the

audit work papers for the Wve years under review;

the Wnal published accounts including Auditors

and Directors Reports; the general correspondence

Wle; audit Wrm management accounting records

showing audit hours charged to the job number by

category of staV; and the oYcial methodology guid-

ance given to each member of staV of the Wrm.

Three individuals were seniors on this client

over the Wve-year period (referred to hereafter as

S2, S3 and S4). All three had since been promoted

to manager and were still employed by the Wrm.

All were available for interview at the time the

Weldwork was undertaken and semi-structured

interviews were undertaken with S2 and S4. S3,

who had been involved in the audit from 1997 to

2000 from staV level up to manager level, was

very interested in the case study and regularly

stopped by for casual conversations, to give opin-

ions, to help with understanding the work papers

and to explain how the methodology had been

applied. The latest version of the software used to

support the methodology was also made available.

Given the extent of the documentation and the

limited time available, detailed review of the work

papers was restricted to three years 1996, 1998

and 2000. The work papers for the intervening

years were reviewed and some data was collected,

but in less detail.

Notes were taken during the course of each

interview and a detailed recollection of the inter-

view based on the notes was written up immedi-

ately afterwards. Copies of some documentation,

such as the oYcial guidance on the methodology,

and some print-outs from the accounting Wrms job

costing records, were provided and this documen-

tation has been retained as part of the case study

database (Yin, 1994).

An interesting feature of the study, which was

not anticipated at the outset, was the evolution of

the oYcial BRA methodology over the Wve years

covered by the case study. During the Wve-year

period under review, two updates of the original

version of the methodology were issued. Copies of

each of these were obtained to assist in the inter-

pretation of the audit work papers. A draft copy of

the next version which was to be piloted for audits

for the year ended December 2001 was also

obtained. While the purpose of this paper is not to

present a detailed analysis of the changes from one

version to another, it is notable that areas which

caused controversy in implementing the approach

were related to changes made in the diVerent ver-

sions of the global methodology, which demon-

strates that continued development of the

methodology by the administrators involved inter-

action with experience from implementation in

practice.

Following the initial analysis of the data and the

preparation of an early draft of the Wndings, follow

up interviews were conducted with P2 and S2,

where the Wndings were discussed. Both conWrmed

that the Wndings were consistent with their general

experiences of implementation.

The discussion in subsequent sections attempts

to communicate the Wndings of the study through

analysis of three main themes. The Wrst section dis-

cusses changing the focus of the audit to business

risk and considers the impact on the identiWcation

of risks. The second section analyses changes in the

nature of the audit work actually performed, and

discusses the diYculties of implementing change.

The third section considers the impact of the BRA

on cost and revenues.

448 E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461

Changing the focus to business risk and business

processes

This section provides a description of the manner

in which key concepts of the BRA were operationa-

lised through changes in the audit methodology. It

also explores the reasons why audit staV reported

that they found the BRA more judgemental and

ambiguous than the previous approach.

Changing the focus from Wnancial statements

to business risk

The pre-existing methodology applied on the

1996 audit used a sequential, word-based, standard

audit planning work programme which led the

audit senior through the planning in a structured

fashion. Risks were identiWed, audit work pro-

grammes were developed and work papers were

organized primarily with reference to individual

Wnancial statement captions. These structures sup-

ported the Wnancial statement focus of the tradi-

tional audit risk model approach of the 1980s and

early 1990s. The BRA envisaged a much broader

understanding of the business to support the

assessment and analysis of business risks. To facili-

tate the acquisition of this understanding and the

assessment of risk, the methodology provided Wve

separate computer based modules which are

described in Table 1.

In order to change the focus of risk assessment

from the Wnancial statements to the business as a

whole, two important changes were made to the

methodology. First, only one of the planning mod-

ules described in Table 1, the preliminary analytical

review activity, was directly related to the Wnancial

statements, and even there emphasis was placed on

key operational data and on future as well as past

performance. All of the other modules were

designed around the business and not the Wnancial

statements. Second, the audit work papers were

organised around the identiWed risks instead of

Wnancial statement captions. Both of these changes

could be expected to be signiWcant forces encourag-

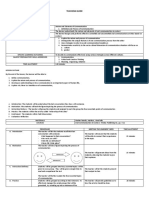

Table 1

The Wve modules of the audit process dedicated to assessing risks under the BRA

1. Evaluation of the clients risk management process

The Wrst module was a tool to support the evaluation of the clients risk management process. This module was a computer-based,

structured decision aid that evaluated the risk management processes at a strategic level in the client organization. It was

supported by a speciWc section in the Wrms proprietary database which included studies, best practices and other resources.

2. Analysis of client business environment

The second module was designed to analyse the industry and the environment in which the client operates and was supported by

relevant industry-wide analysis from a proprietary knowledge database. This analysis resulted in the identiWcation of critical

business processes.

3. Preliminary analytical review (PAR)

The third module was a software tool available to support the PAR. The audit team did not make use of this tool. However, the

analyses performed in the manually produced PAR for each of the three years were compared. In 1996, under the old methodology,

a high-level variations analysis and a ratio analysis were performed. After the implementation of the BRA, the PAR was extended

to include high precision variation analyses (e.g., by month and by product), key performance indicators used by management, and

other management accounting data. This review was updated at year end.

4. Consideration of business risks

The Wrm described the fourth module as a framework for systematically understanding and identifying the types of business risks

threatening the organization as a whole or speciWc business processes within the organization ... it also supports a common language

for communication regarding business risks and business risk management. This tool was also supported by the Wrms proprietary

database, which allowed the audit team to further investigate each risk speciWed and to obtain industry speciWc guidance on that risk.

5. Information Xows

The Wnal module was intended to facilitate the understanding of signiWcant information Xows and identiWcation of information

processing risks. The software included a tool to support the creation and modiWcation of process diagrams and the documentation

of risks and controls within those processes. Industry-speciWc templates were available within the Wrms database to support this.

Alternatively, memos describing procedures, risks and controls could be used to document critical processes.

E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461 449

ing staV to think about the audit diVerently. The

assessment of risk was supported by all Wve mod-

ules and the methodology stressed the interrelated

nature of the modules in assessing risk. The soft-

ware included a summary Risk Tracker, to docu-

ment risks from all Wve modules as soon as they

were identiWed and to drive further audit work.

The seniors generally felt that the software tool-

set which supported the Wve planning modules of

the new approach genuinely helped the audit team

to get a better understanding of the business and

industry. They suggested that it helped the team to

think about business risk and represented a signiW-

cant improvement over the checklist approach

of the old methodology. However, all of the seniors

felt that applying the new methodology was a

much more judgemental process. The presence of

signiWcant elements of structure to support risk

analysis did not remove ambiguity and the need

for judgement. Discussion with P2, S2 and S4 high-

lighted signiWcant reasons for this. Under the old

methodology risk analysis was carried out primar-

ily on a Wnancial statement caption by caption

basis, which gave the seniors a Wnite number of

captions to consider, whereas under the BRA busi-

ness risks were to be identiWed from what P2

referred to as a universe of business risks.

According to the partners, this created a sense of

insecurity as to whether all relevant risks had been

identiWed. Risk assessment was a more ambiguous

process and demanded more from staV at relatively

junior levels who were used to dealing with a

highly structured methodology.

There was also evidence that, despite the Wve

modules to guide the identiWcation of business risk,

the seniors actually identiWed the risks in diVerent

ways. This did not reXect the integrated approach

conceived by the methodology. In 1998, it is clear

that S3 relied heavily on the framework for consid-

eration of business risks (the third module described

in Table 1) in identifying the risks for further audit

consideration. The risks identiWed on the risk

tracker in the work papers were comprised entirely

of risks identiWed when completing this module, and

the language used to describe those risks was also

taken directly from this module. In 2000 S4 did not

use any links to the risk summary throughout the

Wve modules, but approached the risk summary as a

blank sheet of paper after completing the Wve risk

assessment modules. S4 explained that this was

where the thinking would start and would have

reference to the Wnancial statements and prior year

work papers when considering risks. This resulted in

diVerent categorization of risks on the risk tracker

by the three diVerent seniors (S2, S3 and S4) who

prepared the risk summaries. They also used diVer-

ent terminology to describe similar risks. For exam-

ple, S3 classiWed the risk associated with the

warranty provision under the heading product or

service failure whereas S4 classiWed this risk under

the heading judgements and estimates, which

encompassed other estimation risks. The sense of

insecurity created by the potential for variation in

the risks identiWed, and consequently in the nature

and extent of the audit work, seemed to create a

need for a mechanism to ensure the completeness of

the audit risks identiWed. As a result of these diYcul-

ties, the global methodology was amended to

require an initial risk assessment by partners.

Subsequent business risk analysis by the audit team

was aimed at validating this initial risk assessment

and identifying other risks. The initial risk assess-

ment was seen as having a role to put boundaries on

the scope of the risks to be addressed by audit staV,

who otherwise could potentially get lost in the uni-

verse of business risk.

The lack of a risk tracker prepared on a compa-

rable basis in 1996, and the diVerent terminology

and categorization of risks in 1998 and 2000, made

it problematic to prepare a sensible comparison of

risks identiWed across each of the years 1996, 1998

and 2000. Nonetheless, there are some noteworthy

comments that can be made regarding the identiW-

cation of risks after the implementation of the

BRA. Risks which were directly related to Wnancial

statement captions were largely the same both

before and after implementation. The only signiW-

cant diVerence was that the risks were speciWed

more precisely, as opposed to denoting the related

account captions as risky (e.g. risk of credit default

as opposed to the debtors caption being considered

risky as a whole). Similarly, after the implementa-

tion of the BRA, speciWc aspects of the informa-

tion system were identiWed as risks. However, there

was little change in the audit approach to informa-

tion systems.

450 E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461

Two business risks unrelated to the Wnancial

statement captions were identiWed after the imple-

mentation of the BRA which had not previously

been identiWed as risks. Authority and limit (risk of

unauthorized transactions) was classiWed as a mod-

erate risk in both 1998 and 2000. Capacity (moder-

ate risk) was classiWed both as an opportunity to

improve the clients business and as a business risk

in 1998, whereas it was considered only an opportu-

nity to add value in 2000. The inclusion of previ-

ously unidentiWed risks on the risk tracker suggests

that seniors were taking a broader view of the busi-

ness. However, the identiWcation and summariza-

tion of risks is not important for its own sake, rather

it is important because it potentially drives diVer-

ences in the nature and extent of audit work done.

This is examined in a later section of the paper on

changes in the nature and extent of audit work.

Removing the distinction between planning and audit

work

In common with most methodologies utilizing

the audit risk model, the previous methodology of

this Wrm had a very clear distinction between audit

planning and evidence collection. At the end of the

planning, the audit approach had been decided on

and work programmes were agreed. Field work

comprised the completion of the work set out by

the work programme. Under the BRA there was

no clear distinction between planning and Weld-

work. A signiWcant part of the risk assessment pro-

cess involved the analysis of critical business

processes in order to identify risks and related con-

trols. Unlike Wnancial statement balances, risks

cannot be substantiated; logically they can only be

audited by auditing the controls over such risks.

The BRA implemented by this Wrm required that

controls over risks were identiWed, evaluated and

tested. Where controls over a risk were found to be

eVective, the risk was considered reduced to an

acceptable level. In this case no further audit

work was to be performed unless speciWcally

required to comply with GAAS. Where there were

control deWciencies, and hence residual audit risk,

additional audit work of a substantive nature was

required in respect of Wnancial statement balances

potentially impacted by the risks. Thus the BRA as

implemented by this Wrm envisaged a largely con-

trols-based approach to the audit. This represented

a substantial shift in emphasis from the audit risk

model approach, where it was possible to perform

a wholly substantive audit if this was considered to

be more eYcient than testing controls.

Under the previous approach, work pro-

grammes for compliance and substantive work

were developed from standard schedules of audit

tests. These work programmes, which were an out-

put of the audit planning process, eVectively put

boundaries on the audit for the audit staV. Under

the BRA the audit approach developed as the

audit progressed from a prima facie stance that

controls testing would be used where possible. The

methodology was set out as a process whereby the

question was constantly asked Have we addressed

this risk? Thus, the evidence programme devel-

oped as the audit progressed, requiring continual

judgements on the part of the senior. Audit staV

perceived the BRA process as a more Xexible and

unstructured process.

The BRA was intended to focus auditors atten-

tion on business risk by weakening the link

between the risk assessment process and the Wnan-

cial statements, and audit work was to be driven by

identiWed risks rather than Wnancial statement cap-

tions. However, the changes in the nature and

boundaries of audit work created potential con-

Xicts with practitioners existing conceptions of

what was good practice and necessary to deliver

a legitimate audit process. It was clear that in prac-

tice the seniors found that determining the mix of

audit work was a much more ambiguous, and con-

sequently diYcult, task when the boundaries pro-

vided by standard work programmes and Wnancial

statement captions were removed.

Changing the nature of the audit work

This section examines the actual changes in the

nature and extent of audit work after the imple-

mentation of the BRA and explores the diYculties

experienced in achieving the changes in audit test-

ing envisaged by the BRA.

As the working papers were organized around

identiWed risks rather than account captions, pre-

E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461 451

paring a comparison of the nature and extent of

work done by account caption over the three years

examined was not straightforward. In order to

study whether the logic of the new methodology

was followed in practice, Table 2 summarizes the

nature of the audit work in respect of each risk

identiWed on the risk trackers in 1998 and 2000,

focusing particularly on the nature of controls test-

ing. This table follows the intended format of the

Wles after implementation of the BRA. Table 3 on

the other hand summarizes audit work done by

Wnancial statement account caption for 1996, 1998

and 2000, analyzed into four categories: tests of

controls, tests of detail, low precision analytics and

high precision analytics.

1

The signiWcant features

of both tables and the extent to which the nature of

testing changed after implementation of the BRA

are considered in the following discussion.

The guidance issued to staV was explicit about

the objective of decreasing the amount of substan-

tive testing to be performed:

The assessment of client risk controls also

provides a basis for transitioning from lim-

ited to extensive reliance on client risk con-

trol processes and developing value added

insights on improving client risk control

processes Our previous emphasis on sub-

stantive tests as the primary or only method

of managing residual audit risk will decrease

signiWcantly.

Table 2 highlights diYculties in achieving a last-

ing move to an audit designed to address risks and

related controls. In 1998, while the audit team did

follow the logic of evaluating and testing controls

over risks envisaged by the BRA, substantive test-

ing on material accounts remained very stable

throughout the period covered by the study. In the

1

Low precision analytics refers to relatively simple analytical

review work, such as reviewing for unusual items and year on

year comparisons of numbers. High precision analytics may in-

volve a greater degree of detail, for example looking at monthly

Wgures and distributions and analysing sub-populations, and

work that involves more deWned analytical expectations, such

as predictive testing (see notes to Table 3).

Table 2

Analysis of controls testing after implementation of the BRA

a

There was no reference to the evaluation or testing of controls in relation to the obsolescence provision in 2000, and no speciWc

statement that they were relied on. The provision was tested by the performance of a CAAT on the computation of the provision. This

has been interpreted as a substantive test, although such tests can provide evidence of the operation of controls.

b

S D speciWc controls; P D pervasive controls; M D monitoring controls.

Risks identiWed on risk

summaries

1998 2000

Controls

design

evaluated

Controls

tested

Controls

relied on

Additional

substantive

work done?

Controls

evaluated

Controls

tested

Controls

relied on

Additional

substantive

work done?

Obsolescence

a

S, P, M

b

S, P, M Yes Yes No No No Yes

Credit default S, P, M S, P, M Yes Yes No No No Yes

Tax and related parties No No No Yes No No No Yes

Valuation of Wnancial

instruments

S, P, M No No Yes No No No Yes

Foreign currency

translation

S, P, M No No Yes No No No Yes

Performance incentives S No No Yes No No No Yes

Warranty provision S No No Yes No No No Yes

Authority and limit S, P, M S, P, M Yes No According to S4 it was felt this was adequately

addressed in previous years and decision was taken

to do no further work

Information systems

integrity and

infrastructure

S, P, M S, P, M Yes No According to S4, Wrm specialists did full assessment

of the clients information system in 1999, which

was updated in 2000

Access S, P, M S, P, M Yes No N/A N/A N/A N/A

Capacity S, P, M S, P, M Yes No N/A N/A N/A N/A

452 E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461

Table 3

Summary analysis of the nature and extent of audit work in each of the three years examined in detail

This schedule does not purport to represent all of the audit work that was performed on this audit. Other areas of audit work such as

related parties, going concern, fraud risk assessment, commitments and contingencies, subsequent events etc. were completed but are

not included in the summary presented here.

a

Materiality: The summary of work done includes a materiality weighting for each account, where 0 represents aggregate balances

which are less than materiality, 1 represents balances which are between 1 and 4 times materiality, 2 represents balances which are

between 5 and 10 times materiality and 3 represents balances with are in excess of 10 times materiality. In the case where captions fell

into more than one category over the three years, the range of materiality is given. This helps to illustrate the stability of the balance

sheet relationships over the period of the case study.

Captions Material

a

1996 1998 2000

CT

b

TD

c

LPA

d

HPA

e

CT TD LPA HPA CT TD LPA HPA

Fixed assets

Tangible assets 1 2 Y Y Y Y

Intangible assets 0 2 Y Y Y Y

Financial assets 23 2 Y 2 Y 2 Y

Current assets

Stock 3 3 Y Y 3 Y 1 Y

provision 3 Y Y 3 Y CAAT

f

CAAT Y

Due from aYliates 01 2 Y 2 Y 2 Y

Trade debtors 3 2 Y Y 2 Y Y 2 Y Y

provision 3 Y Y Y 3 Y 3 Y Y

Other current assets 1 Y Y Y

Current asset investments 3 3 Y 3 Y 3 Y

Bank and cash 13 3 Y 3 Y 3 Y

Current liabilities

Bank overdrafts 3 3 Y 3 Y 3 Y

Trade creditors 1 Y Y Y

Due to aYliates 3 2 Y 2 Y 2 Y

Other short term

creditors/accruals

3 3 Y Y 3 Y 3 Y Y

Provisions

Pension 0 2 Y 2 Y 2 Y

Warranty provision 1 3 Y Y 3 Y Y 3 Y Y

Deferred income 2 3 Y 3 Y 3 Y

Shareholders equity

and reserves

3 1 Y 1 Y 1 Y

ProWt and loss

Turnover 3 Y Y Y Y Y Y

Cost of sales 3 Y Y Y Y Y Y

Gross proWt Y Y Y Y Y Y Y

G&A 3 2 Y Y 1 Y 1 Y

Selling expenses 3 2 Y 2 Y 2 Y

Other income 2 Y Y Y 1 Y

Interest expense 1 Y Y Y Y

Exchange loss 1 2 Y 2 Y 2 Y

Taxes 1 3 3 3

Business risks

Access and information

systems integrity

Y Y

Authority and limit Y N

Capacity risk

g

Y

E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461 453

case of credit default risk and obsolescence risk,

which relate to material judgemental balances in

the accounts, even though controls were tested and

the work papers explicitly stated that they were

relied on, traditional substantive work was also

performed. This represented testing levels in excess

of that required by the methodology. Table 2 also

shows that in 2000 controls were assessed as

ineVective for all of the risks identiWed on the risk

tracker, with all of the risks being addressed by tra-

ditional substantive work on the account captions

related to the identiWed risks. This resulted in an

audit approach which was very similar to the

approach in 1996 under the pre-existing methodol-

ogy. Table 3, which summarizes the work done by

account caption, tells a similar story. This table

illustrates that the only year in which a signiWcant

amount of controls testing took place was 1998,

and even then there was very limited reduction in

substantive testing. The only change in tests of

details was a reduction in the extent of substantive

testing on tangible assets and general and adminis-

trative expenses.

The BRA also envisaged greater reliance on

high precision analytics. Table 1, which describes

the risk assessment modules, notes an increase in

the use of high precision analytics for the prelimi-

nary analytical review and this analysis was

updated at the Wnal audit. Other than this, Table 3

shows little evidence of signiWcant substitution of

high precision analytics for other forms of substan-

tive testing.

Interviews with the seniors and partners

attempted to probe the reasons why initial eVorts

to move towards controls testing were accompa-

nied by limited reduction in substantive testing and

followed by what appeared from the Wles to be a

return to a more traditional substantive approach

by the fourth year after implementation. Three sig-

niWcant issues which appeared to contribute to this

pattern of behavior are discussed below.

Problems with linkage

From the earliest discussion with seniors and

partners in this study, it became apparent that

there were problems linking the evidence collected

in relation to the risks and related controls with

Wnancial statement amounts. Although it may be

generally accepted that business risk is related to

audit risk, it seemed that practitioners were

uncomfortable with the inference involved in con-

cluding on the veracity of Wnancial statements

based on evidence supporting the existence of con-

trols over business risks. S2 noted that this prob-

lem did not just relate to staV, but that managers

and in some cases partners were uncomfortable

about linkage. S1 commented that it was common

for line managers to request a senior to prepare a

summary of work done by account caption, in

order to bridge this gap. This problem may reXect

a more generic problem of linkage between audit

work done and an opinion expressed on Wnancial

statements, which was exacerbated by changing the

focus from Wnancial statement risk to business risk.

This issue is taken up in the implications section of

the paper.

This question of linkage was discussed with

both partners. P2, who was involved in the develop-

ment of the methodology, explained that there was

a controversy at an international level between

those who considered that focusing on the Wnancial

Table 3 (continued)

b

CT: Tests of control. This table indicates whether controls were tested in a particular area; however, it does not attempt to quantify

the extent of the control testing in each area. The nature and extent of control testing is further analyzed in Table 2.

c

TD: Tests of details. A relative weighting of 1 (limited work) 2 (moderate amount of work) or 3 (signiWcant amount of work) was

given to the extent of tests of details. These weightings are necessarily subjective as no objective measure is available, but reXect the

authors experience of auditing practice.

d

LPA: Low precision analytics. Under the LPA column, the designation Y indicates where simple analytical review work has been

performed. Examples of LPA include year on year variations analysis or review for unusual items.

e

HPA: High precision analytics. Procedures such as predictive testing or detailed variations analysis, such as by-month or by-prod-

uct analyses, are considered to be HPA.

f

See Footnote a to Table 2.

g

Not classiWed as a business risk in 2000.

454 E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461

statements at an early stage in the audit had the

potential to distract the audit team from a business

risk perspective and those who felt that restructur-

ing the audit, including the audit work papers,

entirely around business risk led to a concern that

all Wnancial statement risk was not addressed. This

debate was eVectively resolved in favour of tighter

linkage between risks and Wnancial statements and

the requirement for the audit team to produce a

linkage schedule, cross referencing the Wnancial

statement captions to work done in addressing

business risks, was introduced for audits for years

ending 31 December 2000.

Evidence related to high level controls

A second issue in the implementation of the

BRA was the suYciency of evidence available to

support the operation of high level controls. The

logic of the BRA approach suggests that if the

auditor can identify the sources of business risk

and ensure that the client has appropriate systems

to monitor and manage that risk, there is little

value in extensive detailed testing. The BRA envis-

aged a change in the balance of audit testing from

large volumes of low-level transaction controls to

high-level monitoring or supervisory controls. This

was to be achieved by classiWcation of controls as

speciWc, pervasive or monitoring. The audit team

was required to evaluate the design of all three

types of controls in relation to identiWed risks, but

only pervasive and monitoring controls (i.e. high-

level controls) were to be tested and if they were

found to be operating eVectively reliance was

placed on these controls. SpeciWc risk controls,

which are typically transaction level controls, were

only to be tested where pervasive or monitoring

controls were considered ineVective.

Auditors had diYculties obtaining what they

considered to be suYcient evidence for the opera-

tion of high level controls, and therefore realizing

the intended payoV from the anticipated reduction

in testing large samples of transaction level con-

trols. Table 3 highlights the fact that, despite the

clear hierarchy in the type of control to be tested

according to the oYcial methodology, in every

instance where staV explicitly relied on controls in

1998, all three types of control were tested. This

represented controls testing levels in excess of that

required by the methodology and is likely to have

contributed to the substantial increase in audit

hours (discussed in the next section). It would

appear that audit staV were reluctant not to

employ established procedures that they regarded

as good practice to give the audit an adequate evi-

dence base.

Discussion with the seniors about the reasons

for testing all three types of controls suggested that

they were uncomfortable with the suYciency of the

evidence provided by high-level controls alone.

They questioned the sensitivity of those types of

controls to identify and correct misstatements,

especially in the case of signiWcant judgements and

estimates, such as a bad debts provision. The diY-

culty of Wnding evidence to support the operation

of high-level controls was noted by S1, citing the

tendency of audit staV to document work done on

high level-controls with comments such as The

Wnancial controller stated that he reviewed.

This senior commented that staV often had to be

sent to seek further documentary or corroborative

evidence that reviews had taken place. Even with

such additional procedures, auditors remained

uncomfortable with this soft type of evidence.

The evidence available to support the existence

and operation of high level controls fell short of

the practitioners perceptions regarding what con-

stitutes suYcient appropriate evidence. Concerns

with the ability of high level controls to identify

material Wnancial statement misstatement were

also echoed by standard setters involved in draft-

ing the IAASBs auditing standards in response to

the development of the BRA (Curtis & Turley,

2005).

The diYculties experienced in replacing sub-

stantive procedures with softer evidence on high

level controls could be interpreted as a problem of

displacing highly institutionalized procedures.

However, practitioners must personally answer to

peer reviewers and the courts for the quality of the

audit performed, which is assessed on the basis of

the documented audit Wles and not the tacit knowl-

edge or comfort level of the practitioner. Even if

the assessment of business risks and testing of high

level controls over these risks provides the best

assurance on the veracity of Wnancial statements,

E. Curtis, S. Turley / Accounting, Organizations and Society 32 (2007) 439461 455

as is claimed by proponents of the BRA, practitio-

ners seek to produce a legitimate defensible record

of the audit which conforms to institutional pre-

scriptions of what a set of audit Wles should look

like (Dirsmith et al., 1985).

Time and skills required for controls testing

A further issue in the implementation of the

BRA related to the time, eVort and skills required

to document business processes, identify risks and

controls within those processes, and design tests

for those controls. It was evident from the Wles and

discussion with the seniors that a substantial

amount of time was invested in these activities in

the early years of implementation. Discussion with

the partners about the extent of and commitment

to a risk/controls based audit revealed that both

partners had some concerns about the audit staVs

ability to map critical processes, identify risks and

related controls and devise testing plans for those

controls eYciently and eVectively. Both partners

stated that staV required signiWcant training to per-

form these functions eYciently. In relation to the

2000 audit, both the manager and senior were

asked whether controls were deemed ineVective

purely on eYciency grounds, or whether the assess-

ment reXected a true appraisal of the controls,

which was the intended outcome of the BRA audit.

The manager suggested that eYciency consider-

ations had dominated, although the senior quali-

Wed this (in a separate interview) suggesting that

it was felt that suYcient controls work had been

done over the previous few years, so a largely sub-

stantive approach was taken in 2000. Despite the

substantial amount of controls work done over the

period 199699, the Wles explicitly stated that con-

trols were not relied on in 2000. This contrasts with

the partners who expressed the view that going

back to the days of balance sheet bashing (a

term used by S2 to describe a wholly substantive

audit approach) was seen as undesirable and con-

Wrmed the continuing commitment to improving

staV skills in this area.

There may be more than one explanation for

the diYculties in achieving the changes in the

nature of audit testing which were envisaged by the

BRA. It is possible to argue that the reluctance to

substitute the testing of high level controls and

high precision analytics for traditional substantive

testing is a straightforward story of anchoring

behavior by practitioners. However, it may be that

partners and managers perceive the legitimacy of

the audit Wle, which they personally must defend,