Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Health Promot Pract 2010 Coveney 515 21

Health Promot Pract 2010 Coveney 515 21

Uploaded by

Carmen Greab0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

27 views8 pagesacademic article

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentacademic article

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

27 views8 pagesHealth Promot Pract 2010 Coveney 515 21

Health Promot Pract 2010 Coveney 515 21

Uploaded by

Carmen Greabacademic article

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 8

http://hpp.sagepub.

com/

Health Promotion Practice

http://hpp.sagepub.com/content/11/4/515

The online version of this article can be found at:

DOI: 10.1177/1524839908318831

2010 11: 515 originally published online 30 May 2008 Health Promot Pract

John Coveney

Analyzing Public Health Policy: Three Approaches

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

Society for Public Health Education

can be found at: Health Promotion Practice Additional services and information for

http://hpp.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Email Alerts:

http://hpp.sagepub.com/subscriptions Subscriptions:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Reprints:

http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Permissions:

http://hpp.sagepub.com/content/11/4/515.refs.html Citations:

What is This?

- May 30, 2008 OnlineFirst Version of Record

- Aug 5, 2010 Version of Record >>

at Uni Babes-Bolyai on March 25, 2014 hpp.sagepub.com Downloaded from at Uni Babes-Bolyai on March 25, 2014 hpp.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Analyzing Public Health Policy: Three Approaches

John Coveney, PhD

to be offered choice of services. Thus, the free market

approach, which is attractive to many Western economies,

requires substantial modification and tempering, informed

by policy. Last, decision making in health care frequently

involves life-and-death decisions, which are unparalleled

in other areas of public and social policy.

There has been, in many Western countries, a distinct

shift in political thinking and governance since the

Second World War. In place of welfare-oriented state

services, a move has been made toward smaller govern-

ment, publicprivate partnerships, and market-driven

economies. In the area of health, changes in the nature

and environment of health care and other service delivery

have become second nature to many health professional

and management groups, and policy has become founda-

tional to these changes. The importance has been stressed

of developing what has been called policy acumen to

understand the politicized complexity of this changing

environment (Jones & Salmon, 2001). For those in public

health, where the role of government is fundamental to

the fruition of initiatives that reduce harm and prevent

disease, an understanding of policy as a process and a

point of advocacy is critically important (Ryder, 1996).

Thus, the analysis of policy becomes an important aspect

of public health practice.

>WHAT IS POLICY ANALYSIS?

Traditionally, policy analysis has been defined as deter-

mining what governments do, why they do it, and what

difference it makes (Dye, 1976). More recently, such analy-

sis has become concerned with examining the processes of

governance and policy advocacy, rather than with purely

focusing on government itself. This is especially true in an

area such as health, where a variety of governing structures

Policy is an important feature of public and private orga-

nizations. Within the field of health as a policy arena,

public health has emerged in which policy is vital to deci-

sion making and the deployment of resources. Public

health practitioners and students need to be able to

analyze public health policy, yet many feel daunted by the

subjects complexity. This article discusses three

approaches that simplify policy analysis: Bacchis Whats

the problem? approach examines the way that policy rep-

resents problems. Colebatchs governmentality approach

provides a way of analyzing the implementation of policy.

Bridgman and Daviss policy cycle allows for an appraisal

of public policy development. Each approach provides an

analytical framework from which to rigorously study pol-

icy. Practitioners and students of public health gain much

in engaging with the politicized nature of policy, and a

simple approach to policy analysis can greatly assist ones

understanding and involvement in policy work.

Keywords: public health; policy; policy analysis; Foucault

T

he role played by policy is now regarded to be cru-

cial in the organization and management of con-

temporary Western society. In a range of public and

private organizations and institutions, workers and man-

agers increasingly refer to and rely on policy to guide and

legitimize their actions (Shore & Wright, 1997). However,

the nature of policy depends on the policy area. Palmer

and Short (1998) point to three distinctive features that

make health policy different from other policy arenas.

First, the influence of the medical profession in health

care in general and in policy in particular is unequaled by

professions in other areas, such as education or welfare.

Second, given the complex, sometimes monopolistic

nature of health care systems, it is difficult for consumers

Health Promotion Practice

July 2010 Vol. 11, No. 4, 515-521

DOI: 10.1177/1524839908318831

2010 Society for Public Health Education

Authors Note: The author would like to acknowledge the contribution

to early ideas by Dr. Christine Putland, and he would like to thank the

students who have taken his course, PHCA 9200 Public Health

Studies. Address correspondence to John Coveney, PhD, Department

of Public Health, Flinders University, Box 2100, Adelaide, South

Australia; e-mail: john.coveney@flinders.edu.au.

515

at Uni Babes-Bolyai on March 25, 2014 hpp.sagepub.com Downloaded from

are at play; for example, professional, patient, and com-

munity groups and private interests all play an important

role in determining health policy in a variety of health

environments (Blank & Burau, 2004). The develop-

ment of policy analysis has taken place in academic

areas such as policy studies and political science,

which have been concerned with the examination of

public policy. These academic disciplines have devel-

oped approaches to the practice of policy analysis,

and it is from these that applied disciplines such as

health have taken their lead.

In health, much policy analysis has tended to be dom-

inated by health service policy activity. Perhaps this is

not surprising given that, according to Baume (1995),

much of what passes as health policy in a country such

as Australia has concerned hospital service agreements,

health care service reform, and national government

health service initiatives. In public health, policy analysis

has been confined to traditional public health policies con-

cerning air, sanitation, water, housing, and so on. However,

there has been a developing interest in a broader analysis

of not only policy that affects the publics health but also

adjacent policy advocacy in areas such as tobacco control,

HIV/AIDS, and food and nutrition, to name but a few.

Insights drawn from these areas have been important in

providing an understanding of decision making and sub-

sequent policy development. For example, a recent policy

analysis by Bryan-Jones and Chapman (2006) confirms the

existence of incrementalismthat is, small and insignifi-

cant policy changes instead of substantial reformin the

regulation of smoke-free environments in bars and clubs in

New South Wales, Australia. In their examination of

HIV/AIDS policies in Africa, Siedel and Vidal (1997) iden-

tify the different ways in which HIV/AIDS has been posi-

tioned in policy and the consequences for funding and

services in a number of African countries. And Nestle

(2003) analyzes U.S. food and nutrition policy for evidence

and consequences of the influence of the food industry.

The field of public health is therefore a fertile and neces-

sary area of policy analysis.

Why Is Policy Analysis Important?

At a general level, the analysis of policy is important

because, as I have noted, policy has become a central

concept and instrument in the way that modern societies

are organized and managedand it is through policy that

authority is exercised. Many policy outcomes include not

merely the decisions about why and how to act but also

the assignment of resources to support policy implemen-

tation and outcomes. Policy analysis illuminates these

important aspects of public policy.

For public health, however, policy analysis is crucial.

Because public health produces outcomes that individu-

als are unlikely to achieve by themselves (Oliver, 2006)

for example, health promotion and disease preventionit

commonly requires action at many levels of society, fre-

quently concerning government and other institutions

and organizations. Policies inevitably inform these activi-

ties. The analysis of policy becomes a legitimate and

important public health practice for three reasons: First,

in comparison to many other areas of health, public health

is often underprioritized and poorly funded, and practi-

tioners have to debate decisions of resource allocation. It

is only at the level of policy that problem definition, pol-

icy implementation, and resource allocation can be exam-

ined. A rigorous and defensible approach to policy

analysis is needed for credible critique. Second, much

work in public health concerns advocacy (Chapman,

2001), which has required a full engagement with the

political process that incubates policy. An understanding

or analysis of policy is a prerequisite in advocacy work.

Last, in the contemporary context, where so-called

evidence-based policy has ignited much interest, policy

analysis becomes crucial to understanding the extent to

which the rhetoric is supported by practice (Marsden &

Watt, 2003).

For many practitioners and students of public

health, policy analysis appears arcane, complex, and

impenetrable. Whereas Morris (2000) provides a useful,

if humorous, overview of what is involved, a number of

systematic approaches are available.

How Do You Do Policy Analysis?

Perspectives in policy analysis abound, and as Weimer

and Vining (1989) point out, approaches to policy analysis

depend largely on the disciplinary framework used and

the purpose to which the analysis is put. An economic

analysis of a policy arguably requires a different approach

to one looking at potential impact on community capacity

building. Collins (2005) has usefully summarized a

number of policy analysis methodologies that can be

applied to public health. Dunn (1981) suggests that there

are six general procedures that should be incorporated into

policy analysis: solving, defining, predicting, prescribing,

describing, and evaluating. Portney (1986) suggests

three approaches to policy analysis: policy making, cause

and consequences, and policy prescription. And Collins

516 HEALTH PROMOTION PRACTICE / July 2010

The Author

John Coveney, PhD, is an associate professor in the Depart-

ment of Public Health, Flinders University, Adelaide, South

Australia.

at Uni Babes-Bolyai on March 25, 2014 hpp.sagepub.com Downloaded from

herself recommends an eight-step framework for the analy-

sis of health policy.

One of the difficulties that students and practitioners

face when examining public health policy lies in the prob-

lem of applying one tool or one series of steps to the pol-

icy context, given that any number of areas may be of

interestfor example, problem identification, consulta-

tion, implementation. Moreover, as Sabotier and Jenkins-

Smith (1993) point out, a theoretical lens or an explanatory

framework is required; otherwise, it becomes difficult to

distinguish what is likely to be important and what can be

ignored. In other words, the policy analysis approach

depends largely on what aspect of policy is under review.

What follows is not a prescriptive stepwise process that

can be recommended for all aspects of policy analysis.

Instead, three approaches to policy analysis are offered.

Each is explained with an example of the context in

which it might best be used. Whereas these explanatory

frameworks are not exhaustive, they are comprehensive in

their utility; that is, they can be pressed into service in a

number of policy analytic contexts. Moreover, each has

been developed, and each is supported by practice and

theory; thus, they are all robust and highly defensible.

>THREE APPROACHES TO POLICY

ANALYSIS

The Whats the Problem? Approach

The first analytical approaches is the Whats the

problem? framework by Carol Bacchi (1999). Whats

the problem? is actually shorthand for What is the

problem represented to be? because it is the represen-

tation of issues or problems and the subsequent effects

of that representation that interest Bacchi. She distin-

guishes this approach (which focuses on problems)

from much of the work in policy studies (which is con-

cerned with solutions). Indeed, Bacchi goes to some

lengths to differentiate between what she calls problem

solutions analysis and problem representations analy-

sis. The former, she contends, focuses on (a) a belief

that problems exist out there and are available for so-

called objective analysis (what Bacchi calls compre-

hensive rationalists) or (b) a belief that problems result

from political processes that seek to give voice to all

stakeholders and constituents (what she terms political

rationalists). Bacchi is not merely interested in prob-

lem identification but also in what is silenced in this

process. She wants to lay open the assumptions and

values that come into play in policy work. As such, she

provides the following questions to frame this analyti-

cal approach:

What is the problem represented to be, in either a spe-

cific policy debate or in a specific policy proposal?

What presuppositions or assumptions underlie this

representation?

What effects are produced by this representation?

How are subjects constituted within it? What is

likely to change? What is likely to remain the same?

Who is likely to benefit from this representation?

What is left unproblematic in this representation?

How would responses differ if the problem were

thought about or represented differently? (p. 12)

The early questions in this list allow for an examina-

tion of the way in which the issue under consideration

has been problematized, defined here as the extent to

which weight has been given to a phenomenon to give it

moral and political gravity: in other words, to give it

importance. By asking questions about representation,

Bacchi highlights the human and political role played in

policy work: She emphasizes that policies and the prob-

lems they address do not fall fully formed from the heav-

ens. They are constructed. She therefore wants to

provoke consideration regarding the complexion of a

problem, not only in terms of its facets and constituent

parts but also in the way that it has engaged interest and

justification, which is brought out more clearly when

considering the assumptions and presuppositions on

which the representation is based. This point goes to the

heart of the value or moral base on which the representa-

tion is founded. In the question that asks how subjects are

constituted in the representation, Bacchi refers to the way

that various representations bring actors into play, what

their roles are, and how they are likely to affect, or be

affected by, the problem representation. But it is in the

last few questions that Bacchi demonstrates how her

analysis goes beyond mere description of the problem

representation. By asking what is left unproblematic and

how the response would be different under another way

of representing the problem, Bacchi seeks comparisons

with alternatives, which forces a consideration of other,

perhaps more productive, equitable, and socially just

ways of approaching the same area.

Application of Whats the Problem?

Bacchis approach (1999) can be used to analyze a

number of contemporary policy contexts. The one cho-

sen here draws on the current debates in Australia and

in some other countries regarding childhood obesity.

Coveney / ANALYZING PUBLIC HEALTH POLICY 517

at Uni Babes-Bolyai on March 25, 2014 hpp.sagepub.com Downloaded from

This issue has recruited a number of important and pow-

erful stakeholder groups that appear to line up on either

side of a policy divide. According to an Australian federal

government, the problem is represented to be one where

children are not being provided with sufficient guidance

and management by parents, who have the responsibility

for feeding children with nutritious foods and encourag-

ing them to be physically active. Indeed, the then federal

minister of health Tony Abbott is on record as saying, No

one is in charge of what goes into kids mouths except

their parents (as quoted in Fullerton, 2005, n.p.). Within

this representation, parents have total responsibility to

feed children healthily, and attempts must be carried out

at home to manage childrens eating habits (believed to be

the heart of the obesity epidemic). Thus, the problem of

overweight children and their obesity is represented as a

failure of parents in exercising their responsibilities.

Many representatives of the food industry also assume

this view.

Working thorough Bacchis questions, one might con-

clude that the presuppositions and assumptions under-

pinning this representation are as follows: that childrens

food choices and eating habits are the product of parental

influence, that parents have the sole capacity to determine

what children eat, and that factors outside the home are

insignificant in influencing what determines childrens

food choices. The effects of this representation are that,

among other things, the potential influences outside the

direct family environment attract minimum scrutiny and

little regulation and legislationfor example, the promo-

tion and marketing of food to children, the provision of

food to children outside the home (such as at child care

and school), and the various roles played by fast-food out-

lets. Following Bacchi, the principal actors constituted

within this representation are the parents, who as sover-

eigns of the household, exert their influence over their

childrens food choices regardless of the influences exter-

nal to the family environment.

One can speculate in terms of Bacchis questions

regarding what is likely to change and remain the same in

this representation: First, there is unlikely to be a full

examination by the federal government of the role of the

food industry, the broadcasting industry, and the adver-

tising industry in the development of increased body

weight of Australian children over the past 10 years

(Magarey, Daniels, & Bolton, 2001); second, any exami-

nation of the issue by federal government will be limited

to the home environment; last, strategies for addressing

the problem are going to focus on matters of personal

(parental) choice. The benefits of this representation are

probably going to flow to those who support minimum

legislative control of industry activity and instead

endorse codes of industry conduct and other self-regulatory

mechanisms.

Left unproblematic in this representation are the

concerns by various groups about the effects of food

advertising to children, the position of childrens rights

in not being exploited by food marketing, and the

public health consequences brought on by market

forces that promote unhealthy food choices.

A representation of the problem in a different wayfor

example, that obesity in children largely results from the

heavy marketing of unhealthy food productsis the stock

in trade of those groups who oppose the Australian gov-

ernments sole emphasis on parental responsibility

(Coalition on Food Advertising to Children, 2006). What

one can see here is that Bacchis series of questions allows

one to unpack the problem representation of a policy

statement and position. As an approach to policy analysis,

it allows for a close examination of the values and beliefs

that underpin policy statement and positions and the

ways in which these act as normative and taken-for-

granted assumptions. The way that such assumptions

constitute actors while closing down other positions is

made clear. Bacchis approach differs from many in policy

analysis in that it does not question the role of the policy

as such but the positioning of the problem representation

that the policy is then developed to address. As such, it

takes issue with a number of other policy-analytical

approaches that are concerned with problem identifica-

tion and legitimation.

The Whats the problem? approach sits comfortably

within what may be called the social constructionist par-

adigm, which takes issue with the notion of real problems

that sit outside human and political engagement. Instead,

it is informed by the emergence of problems as a conse-

quence of positioning issues within a knowledgepower

contextthat is, the way that understandings are ren-

dered as discourses that carry and amplify moral impera-

tives and, with them, an ability to engage public and

political activity. Much of the thinking in this area is influ-

enced by the work of social theorist Michel Foucault

(1997), and indeed, Bacchi acknowledges an intellectual

debt to him in her Whats the problem? approach. But

Foucaults work has been used in other aspects of policy

analysis, and it is to these that the article now turns.

Colebatch and Governmentality

The work of Hal Colebatch (2003) is representative of

the policy-analytic framework informed by governmental-

ity. The term governmentality was first developed by

Foucault (1991) to describe developments in the ways in

which populations became manageable in Western cul-

tures. Briefly, Foucault points to the way that techniques

for knowing and regulating people through surveys,

demography, medicine, and other forms of surveil-

lance (now attributed to the state) emerged in 17th- and

518 HEALTH PROMOTION PRACTICE / July 2010

at Uni Babes-Bolyai on March 25, 2014 hpp.sagepub.com Downloaded from

18th-century Europe. At the same time, various forms of

self-discipline and the regulation of individuals were

being reified. The result was a regulation of the conduct

of conduct, so to speak, whereby governance is ordered

through a variety of legal, expert, and self-regulating strate-

gies. Indeed, the conjunction of legal, professional and self-

regulatory codes of conduct is entirely germane to the

use of governmentality in Colebatchs analytical frame-

work. Thus, whereas Bacchi examines what the problem

is represented to be, Colebatch examines the ways in

which policies and policy strategies engage when they are

implemented.

Colebatch conceptualizes governmentality in terms of a

vertical and a horizontal axes of policy activity. Put simply,

the vertical axis comprises the activities of authorized

decision makers, such as government jurisdictions and

their executives. An example might be a government strat-

egy or a policy initiative. This engages with a horizontal

level of activities populated by stakeholders, some of

which are government bodies, but others may be profes-

sional organizations, community groups, commercial

interests, and so on, all of whom have a stake in the policy

process and the policy outcome. That stake could be in the

form of advocacy for the cause, adoption of all or part

of policy initiative for local implementation, and even the

oversight of professional conduct of those involved.

Instrumental to Colebatchs analytical framework is the

question, what is the involvement of authority, expertise,

and order in this policy context? And it is the execution of

authority and its legitimation through expertise and order

that structures this governmentality approach.

Application of Governmentality

Colebatch (2003) chooses the following health case to

demonstrate policy analysis using governmentality. Part

of the Commonwealth of Australias Better Health ini-

tiative involved an attempt to decrease the incidence of

sports-related injury; as such, the national sports safety

strategy was launched to address this area. Key to the

strategy was the involvement of a raft of stakeholders from

areas such as injury prevention (physiotherapy and sports

coaching), sport and recreational bodies (at a variety of

levels, national state, local government), and various gov-

ernment agenciesall of which were to be involved in an

accreditation scheme tied to funding. Thus, the vertical

initiative (Better Healths sports safety strategy) horizon-

tally engages with a range of other organizations that legit-

imize, and are simultaneously legitimated by, their

involvement in the policy process. Typical of this hori-

zontal engagement is the involvement of consumer groups

and interest groups, who become crucial to implementing

the policy initiative as it stands but also shaping it to meet

their own ends. Interest groups attain authority by claim-

ing direct experience of the area and problem under con-

sideration, thus justifying their involvement and expertise

in the issue. As such, policy is enacted on behalf of, rather

than by, the government. This government at a distance

is entirely consistent with a governmentality approach,

which analyzes the ways in which policy processes are

amplified and executed outside the direct control of gov-

ernment legislation and regulation.

So far, I have addressed policy analysis that exam-

ines problem representation and policy execution. The

third example of policy analysis directly concerns the

ways in which policies develop as part of public sector

politics and public administration.

The Policy Cycle Approach

A policy cycle describes the ways in which policy is

developed and the various stages of maturity through

which it travels to become an active public document.

Such policy cycles are not new. However, one of the best-

known cycles in Australia is the one developed by

Bridgman and Davis (2002). Essentially, the cycle breaks

down the process of policy development into discrete

activities, one following the next in a sequential, cyclical

fashion. Starting with the activity of identifying the issues,

Bridgman and Davis move through a stepwise sequence of

events describing a range of activities within each. The

other stages include policy analysis, policy instrument,

consultation, coordination, decision, implementation,

and evaluation.

The authors use this process as an ideal way of devel-

oping sound policy but recognize that it is not always

attainable. They also stress that what looks like a march in

one direction is often a dance best described as the ebb

and flow of sophisticated policy debate (Bridgman &

Davis, 2002). All up there is a general recognition of the

cycle representing rigorous policy processes; that is, it is a

framework for developing and implementing policy. For

our current purpose, the cycle becomes less a framework

for developing policy and more a tool for examining pol-

icy processes; in other words, it allows one to undertake

policy analysis. Within each stage of the policy cycle, a

number of criteria are given for successful accomplish-

ment of the task. For example, at the level of consultation,

the authors describe the way in which public consultation

or stakeholder consultation relates to the more intense

consultation demonstrated within the public service

itself (Bridgman & Davis, 2002). These criteria easily lend

themselves as external standards for assessment of policy

competence.

Coveney / ANALYZING PUBLIC HEALTH POLICY 519

at Uni Babes-Bolyai on March 25, 2014 hpp.sagepub.com Downloaded from

Application of the Policy Cycle Approach

The policy cycle approach best lends itself to an analy-

sis of the development of public policyespecially, gov-

ernment legislation. For example, the cycle would be

useful in analyzing the way in which policy was devel-

oped in Australia regarding the regulation of genetically

engineered crops. The documents related to this develop-

ment are reasonable accessible, and the issue came under

the scrutiny of many government and nongovernment

organizations. Thus, mapping the process of developing

the policy is entirely manageable. However, for a policy in

a private domain, the nonaccessibility of the information

may be a barrier to a full analysis using the policy cycle

approach. Thus, the policy cycle requires that the avail-

ability of the journey through which the policy has trav-

eled in its development and that it not hidden through, for

example, commercial in-confidence limitations.

One of the best examples of applying the policy cycle

approach comes from Edwards et al. (2001), who use the

model to unpack four case studies of major social policy

processes in Australian state politics. Each case study rep-

resents a significant social policy reform: the provision of

a youth allowance, the introduction of a child support

levy, a graduate tax for tertiary education, and an employ-

ment policy. The analysis undertaken by the researchers

520 HEALTH PROMOTION PRACTICE / July 2010

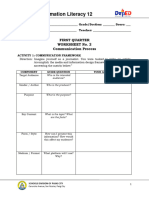

FIGURE 1 The Policy Cycle

SOURCE: Bridgman and Davis (2002) permission granted to reproduce.

at Uni Babes-Bolyai on March 25, 2014 hpp.sagepub.com Downloaded from

takes the form of a rigorous examination at each stage in

the policy cycle. In doing so, they demonstrate how spe-

cific questions can highlight important parts of the policy

development process. Although the analyses do not

address public health, it would be easy to translate to a

public health policy context.

>CONCLUSION

As in other areas, policy analysis in health can appear

daunting. Given the often-complex nature of policy devel-

opment, it is easy to feel overwhelmed by the task of

making sense of and providing a critique of the process. I

presented these three policy analysis approaches because

of their simplicity, which is not to say that they oversim-

plify the issue. Experience has shown that the policy

cycle (Bridgman & Davis, 2001) is best employed when a

macro-analysis of the whole policy-making process is

required, especially at the level of public or government

policy. However, when a micro-examination of policy is

needed, the approaches of Bacchi (1999) or Colebatch

(2003) are recommended. Bacchis approach is useful

when examining the development of policy as problem

representation. In practice, students and practitioners find

the stepwise questioning proposed by Bacchi easy to exe-

cute. Colebatchs use of governmentality is recommended

when the analysis includes the role of constituents and

stakeholders in policy implementation. It is especially

useful in understanding the relationships among govern-

ment, nongovernment, and private investments in policy

implementation.

These three approaches are useful in providing insight

into various parts of the policy process. I should also

emphasize that these tools are useful for not only policy

analysis as such but also the analysis of those instruments

that function as policy, such as guidelines, codes, and

strategies. Practitioners and students of public health gain

much in engaging with the politicized nature of policy,

and a simple approach to policy analysis can greatly assist

in understanding policy work and being involved in it.

REFERENCES

Bacchi, C. (1999). Women, policy and politics: The construction

of policy problems. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Baume, P. (1995). Towards a health policy. Australian Journal of

Public Administration, 54(1), 97-101.

Blank, R., & Burau, V. (2004). Comparative health policy. Basingstoke,

UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Bridgman, P., & Davis, G. (2002). The Australian policy handbook.

Crows Nest, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Bryan-Jones, K., & Chapman, S. (2006). Political dynamics pro-

moting the incremental regulation of secondhand smoke: A case

study of New South Wales, Australia. BMC Public Health, 6, 192.

Chapman, S. (2001). Advocacy in public health: Roles and chal-

lenges. International Journal of Epidemiology, 30, 1226-1232.

Coalition on Food Advertising to Children. (2006). Childrens

health or corporate wealth. Adelaide, Australia: Author.

Colebatch, H. (2003). Policy. Bucks, UK: Open University Press.

Collins, T. (2005). Health policy analysis: A simple tool for policy

makers. Public Health, 119, 192-196.

Dunn, W. (1981). Public policy: An introduction. Englewood

Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Dye, T. (1976). Policy analysis. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama.

Edwards, M., Howard, C., & Miller, R. (2001). Social policy, public

policy. Crows Nest, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

Foucault, M. (1991). Governmentality. In G. Burchell, C. Gordon,

& P. Miller (Eds.), The Foucault effect (pp. 87-104). Hemel

Hempstead, UK: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Foucault, M. (1997). Polemics, politics and problematizations. In

P. Rabinow (Ed.), Ethics: Vol. 1. Essential works of Foucault,

19541984 (pp. 381-390). New York: New Press.

Fullerton, T. (2005). Generation O. Retrieved April 22, 2008, from

http://www.abc.net.au/4corners/content/2005/s1484310.htm

Jones, M., & Salmon, D. (2001). The practitioner as policy analyst:

A study of student reflections of an interprofessional course in

higher education. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 15(1), 67-77.

Magarey, A., Daniels, L., & Bolton, J. (2001). Prevalence of over-

weight and obesity in Australian children and adolescents:

Reassessment of 1985 and 1995 data against new international

definitions. Medical Journal of Australia, 174, 561-564.

Marsden, G., & Watt, R. (2003). Tampering with the evidence: A

critical approach of evidence-based policy-making. The Drawing

Board: An Australian Review of Public Affairs, 3(3), 143-163.

Morris, J. (2000). Playing policy pinball: Making policy analysis

palatable. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and

Mental Health Services Research, 28(2), 131-137.

Nestle, M. (2003). The politics of food. San Francisco: University

of California Press.

Oliver, T. (2006). The politics of public health policy. Annual

Review of Public Health, 27, 195-233.

Palmer, G., & Short, S. (1998). Health care and public policy: An

Australian analysis. Melbourne, Australia: MacMillian.

Portney, K. (1986). Approaching public policy analysis: An intro-

duction to policy and program research. Englewood Cliffs, NJ:

Prentice Hall.

Ryder, R. (1996). The analysis of policy: Understanding the

process of policy development. Addiction, 91(9), 1265-1270.

Sabotier, P., & Jenkins-Smith, H. (1993). Policy change and learn-

ing. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Shore, C., & Wright, S. (1997). A new field of anthropology. In

Anthropology of policy: Critical perspectives on governance and

power (pp. 3-39). London: Routledge.

Siedel, G., & Vidal, L. (1997). The implications of medical, gender

in development and culturalist discourses for HIV/AIDS policy

in Africa. In C. Shore & S. Wright (Eds.), Anthropology of policy

(pp. 59-87). London: Routledge.

Weimer, D., & Vining, A. (1989). Policy analysis: Concepts and

practice. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Coveney / ANALYZING PUBLIC HEALTH POLICY 521

at Uni Babes-Bolyai on March 25, 2014 hpp.sagepub.com Downloaded from

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5820)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (898)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (349)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Raven's Progressive Matrices - Validity, Reliability, and Norms - The Journal of Psychology - Vol 82, No 2Document5 pagesRaven's Progressive Matrices - Validity, Reliability, and Norms - The Journal of Psychology - Vol 82, No 2Rashmi PankajNo ratings yet

- Emcee Drum and LyreDocument5 pagesEmcee Drum and LyreJorgen De Guzman-SalonNo ratings yet

- Rudolfo Trevizo: EducationDocument1 pageRudolfo Trevizo: Educationapi-248454170No ratings yet

- De Thi Thu Tot Nghiep 2020Document5 pagesDe Thi Thu Tot Nghiep 2020Nguyen CuongNo ratings yet

- International Expansion (HR Perspective)Document23 pagesInternational Expansion (HR Perspective)redheattauras67% (3)

- Upsr Trial EnglishDocument16 pagesUpsr Trial Englishbavanesh100% (2)

- Zachary Santiago ResumeDocument2 pagesZachary Santiago Resumeapi-386724916No ratings yet

- Aps SyllabusDocument1 pageAps SyllabusRahul kuamrNo ratings yet

- Assessmentof Schools Evaluation Systemsin EgyptDocument18 pagesAssessmentof Schools Evaluation Systemsin Egyptmidhat mohiey-eldien el-sebaieyNo ratings yet

- LP June 13to16Document8 pagesLP June 13to16cristy olivaNo ratings yet

- Learning Plan 3.1Document4 pagesLearning Plan 3.1Shielo Marie CardinesNo ratings yet

- CO PO Mapping PresentationDocument36 pagesCO PO Mapping Presentationarvi.sardar100% (1)

- Diemberger CV 2015Document6 pagesDiemberger CV 2015TimNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Sketch 3Document3 pagesLesson Plan Sketch 3api-521963623No ratings yet

- Lexi TFolio CV 2Document2 pagesLexi TFolio CV 2Alexandra LeomoNo ratings yet

- Games For Kids: How To Play Bam!: You Will NeedDocument13 pagesGames For Kids: How To Play Bam!: You Will Needapi-471277060No ratings yet

- Exponents Worksheets PDF FreeDocument2 pagesExponents Worksheets PDF FreeEmilyNo ratings yet

- AEPA 036 Flash CardsDocument64 pagesAEPA 036 Flash CardsNicoleNo ratings yet

- Syllabus in Pec 106Document6 pagesSyllabus in Pec 106Clarisse MacalintalNo ratings yet

- Assignment Integrated SkillsDocument14 pagesAssignment Integrated SkillsMaritza Román Rodríguez100% (1)

- Management Plan On SleepDocument3 pagesManagement Plan On SleepMa'am Ja Nheez RGNo ratings yet

- 0 Constitution BL SETA 2017Document48 pages0 Constitution BL SETA 2017Butch CabayloNo ratings yet

- SAC Anthonian Magazine Evelio Special 2010-2011Document36 pagesSAC Anthonian Magazine Evelio Special 2010-2011Dshaman14No ratings yet

- Writ Petition 415/2011 - Muhammad Usman Syed v. COMSATS & 2 OthersDocument32 pagesWrit Petition 415/2011 - Muhammad Usman Syed v. COMSATS & 2 OthersBilal MirzaNo ratings yet

- Physics 1 Syllabus 2015-16Document8 pagesPhysics 1 Syllabus 2015-16api-301989803No ratings yet

- DLL Cookery preparingColdSandwichesDocument6 pagesDLL Cookery preparingColdSandwichesJay JovenNo ratings yet

- Grade 4 Q1 2023-2024 Budgeted Lesson English 4Document2 pagesGrade 4 Q1 2023-2024 Budgeted Lesson English 4Marion Vergara Cojotan VelascoNo ratings yet

- TVL Mil12 q1 Dw2Document3 pagesTVL Mil12 q1 Dw2Joanna May PacificarNo ratings yet

- Unit 31Document3 pagesUnit 31api-271339973No ratings yet